Black alder (Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn.) forests are ecosystems naturally widespread across all of Europe, from southern Scandinavia to the Mediterranean countries, including some regions of North Africa, namely northern Morocco and northeastern Algeria (Jalas & Suominen 1976, Kajba & Gracan 2003). Black alder forest is one type of broadleaved forest, and it has a broad but highly scattered distribution (it represents less than 1 % of forest cover in most countries). Despite this spatial configuration, the total population size of this species is not yet thought to approach threshold values to warrant its inclusion in a threatened category. Thus, the species is listed as Least Concern in the IUCN Red List (Shaw et al. 2014).

Black alder forest is a particular kind of wetland forest. Black alder occurrence is closely related to water availability and high atmospheric humidity during all phases of its reproductive cycle (Bensimon 1985). It commonly occurs in hilly regions, alongside streams and rivers banks, in damp marshy woods and riverside woodlands (Shaw et al. 2014). According to Claessens (2003), black alder forests occur in three main types of wetlands: (i) marshy or swampy sites with sodden soil throughout the year, which constitute the Alnetum community; (ii) riverside sites in which the soil in the rooting zone is well aerated during the growing season (Alno-Padion community); and (iii) hilly sites with high soil humidity (Carpinion community).

Black alder is recognized as an important contributor to forest structure in other wetland ecosystems, and it contributes to the services which they offer (Claessens 2003). For example, Alnus glutinosa plays a key role in biodiversity maintenance by offering habitats for specific flora and fauna, both on the tree itself and in the flooded root system (Dussart 1999). This ecosystem contributes to water filtration and purification in flooded soils (Pinay & Labroue 1986, Schnitzler-Lenoble & Carbiener 1993) because the root system of black alder helps control floods and stabilize riverbanks (Piégay et al. 2003).

In Algeria, few studies have been conducted on alder forests. This is regrettable, as these forests constitute the largest ones in North Africa (Belouahem et al. 2011, Bensettiti & Lacoste 1999, Géhu et al. 1994), and few measures have been taken to protect these ecosystems. In fact, only two sites benefit from indirect conservation measures, based on freshwater bird richness (alder forests of Tonga, and those of Ain Khiar, were classified as RAMSAR sites in 1983 and 2002, respectively).

Identifying species composition and the existing species assemblages, and examining how these species are distributed across the alder forest region in northeastern Algeria, are necessary steps prior to investigating the functioning and dynamics of these ecosystems. Algerian black alder forests represent an extremely original ecosystem of northern affinity throughout North Africa (Géhu et al. 1994) and are characterized by particular geomorphologic, edaphic, and climatic conditions (Morgan 1982). Hence, the main aims of this study were: (1) to inventory the floristic composition of alder forests in El-Kala Biosphere Reserve and its surroundings, (2) to investigate the effect of abiotic factors (soil properties) on species richness and diversity, and (3) to distinguish plant communities based on species composition and to define spatial patterns of these plant communities.

Materials and methods

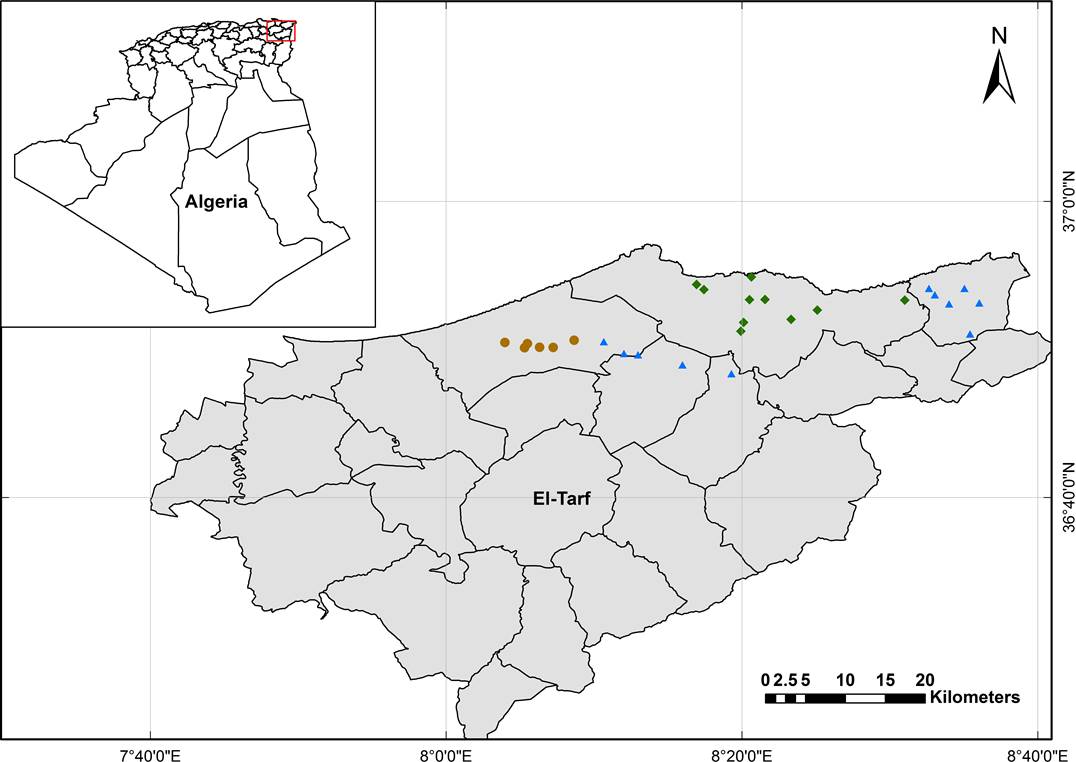

Study area. The El-Kala Biosphere Reserve (KBR hereafter) was created in 1983 by governmental decree no. 83-462 of July 23rd, and classified as Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO on December 17th, 1990. KBR is located at the extreme northeast region of Algeria, specifically in the northeast of Numidia area, between 36° 56’ N, 36° 34’ N, and 8° 12’ E, 8° 41’ E (Figure 1), and it has a surface of 76,438 ha. Elevation at KBR ranges from 100 m a.s.l. near the Oued El-Kebir river, to 1,202 m a.s.l. at Mount El-Ghorra. KBR is characterized by a Mediterranean climate, with dry hot summers followed by wet warm winters. According to climatic data for 2005-2015, the minimum mean monthly temperature is 10 °C in February, whereas the maximum mean is 25 °C in July. Average total annual precipitation is 656 mm, with four months having precipitation < 30 mm (WorldClim, 2.0; Fick & Hijmans, 2017). Geology of KBR is characterized by two formations: the Quaternary, mainly represented by marine and river deposits, and the Miocene, including conglomerate sands and red clays, concentrated in the southeastern portion of the area (Joleaud 1936). Soils in the KBR are mainly brown washed with a variant of forest humus mull acidic Moder (Joleaud 1936).

Figure 1 Map showing the location of El-Kala Biosphere Reserve (KBR) in northeastern Algeria (Projection system: GCS WGS 1984, coordinates in decimal degrees). Blue triangles indicate the exact location of fluvial sites (Fl), green polygones indicate swampy sites (Sw) and brown circles indicate sandy sites (Sa).

Black alder forests of KBR have been widely altered by human activities (e.g., cutting, burning, draining and/or dumping); since that region is immediately close to the sea, those related to tourism and leisure prevail. Thus, being a region with an agricultural vocation, other activities contribute to the disturbance of these areas (i.e., the use of pesticides and the clearing of areas for agriculture).

Vegetation sampling. In order to investigate the floristic composition and spatial patterns of plant species assemblages in alder forests, surveys were conducted between 2016 and 2017 during the peak of vegetation development (spring and summer) (Ozenda 1982). During this time, 28 localities were sampled, which were representative of the three main substrates, i.e., fluvial (Fl), swampy (Sw), and sandy (Sa).

The relevé method developed by the Zürich-Montpellier school for field vegetation studies (Braun-Blanquet 1964) was applied, by using at least the minimum area recommended for these vegetation types (16 m2 for marshland vegetation, and 400 m2 for species-poor forests). We collected species when encountered for the first time or whenever there was uncertainty on their identity. Specimens were identified using Quézel & Santa (1962).

The checklist of botanical families and species was organized alphabetically. Taxonomy and nomenclature follow the classification accepted by THE PLANT LIST database (The Plant List 2013), which is based on the APG III classification system for Angiosperms (APG III 2009). The updating and standardizing of species taxonomy and nomenclature according to APG III (2009) were guaranteed by using the Taxonomic Name Resolution Service v4.0 program (TNRS 2016). Species life forms were assigned based on Whittaker’s (1975) classification system, a modified version of Raunkiaer’s (1934) original classification scheme, which includes the following categories: helophytes (He), amphiphytes (Am), phanerophytes (Ph), hemicryptophytes (Hec), therophytes (Th), geophytes (G), hydrophytes (Hy), chamaephytes (Ch), and epiphytes (Ep).

Soil sampling. Soil samples were obtained with 5 cm diameter cores taken from three points at each site. The soil was sampled to a depth of 25 cm. The three replicate samples were homogenized by hand mixing; large material (roots, stems, and pebbles) were hand-picked and discarded. Soil samples were air-dried and sieved with a 2 mm mesh for laboratory analyses. Soil analyses included determination of organic matter (OM) using incineration method, and pH electrical conductivity (EC) based on a 1:5 soil-water solution using pH/conductivity meter. Next, Practical Salinity (PS) was obtained from EC, according to Fofonoff &Millard (1983). In addition, total lime (TL) was determined using the titration method called ‘calcimétrie de Bernard’ (Fichaut 1989).

Data analyses. Plant diversity was evaluated using species richness (SR), defined as the total number of identified species (Magurran 2004). Further, percent relative richness (RR) was calculated for each family as the number of species contained in that family divided by the total number of species (SR). Occurrence frequency (Occ) was calculated for each species as the number of plots in which the species was recorded divided by the total number of sampled plots (Magurran 2004). Bigot & Bodot (1973) distinguished four species groups according to their occurrences: very accidental species (Vac), with occurrence ˃ 12.5 %; accidental species (Acc), with occurrence varying between 12.5 and 24 %; common species (Cmn), which occur in 25-49 % of records; and constant species (Cst), which are present in 50 % or more of the samples.

Accumulation curves were drawn to evaluate sampling efficiency and to envisage if plant species from the three habitat types (Fl, Sw, Sa) were well represented and could be used for reasonable and significant assessments (Chao & Chiu 2016). For all rarefaction/extrapolation (R/E) curves, we used 500 replicate bootstrapping runs to estimate 95 % confidence intervals, using the “iNEXT” package (Hsieh et al. 2016) in R version 3.4.0 (R Core Team 2017). Accumulation curves were calculated using EstimateS software version 9.1.0 (Colwell 2013).

Soil parameters were compared among the three habitat types through linear mixed effects models (LMMs). Diagnostic quantile-quantile plots, used to examine the appropriateness of the models, revealed a good fit of the data to a normal distribution. Response variables were soil properties, habitat as taken as a fixed effect, whereas Season was declared as a random effect. We also used Tukey contrasts for LMMs for post-hoc comparisons of the different habitat types. These analyses were performed using the ‘lmer’ function of the lme4 package version 1.1-12 (Bates et al. 2015), and the ‘glht’ function of the multcomp package (Hothorn et al. 2013) in R.

Multiple linear regression analyses were used to determine the signs of the relationships between species richness (SR) and soil characteristics (OM, EC, pH, PS, TL). Analysis of variance for regression was used to assess significance (Kozak et al. 2008). Next, Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) was used to set up the spatial pattern in the scattergram. The ordination was fitted using the metaMDS function with Jaccard distances and two dimensions in the vegan package in R (Oksanen et al. 2017). Finally, to evaluate whether species were associated with particular habitats, and thus if they could be considered as indicators of such habitats, we performed an indicator value analysis (Dufrene & Legendre 1997) using the “labdsv” package (Roberts 2016) in R. Taxa were considered good indicators if the indicator value was ± 0.25 (Dufrene & Legendre 1997).

Results

Floristic composition. In total, we identified 354 species belonging to 238 genera and 89 families (Appendix 1). Poaceae (35 species), Fabaceae (31), Cyperaceae (24), Asteraceae (24), Caryophyllaceae (13), Ranunculaceae (13), Lamiaceae (12), Brassicaceae (11), Juncaceae (11), Plantaginaceae (10), and Apiaceae (9) were the most species-rich families, accounting together for 54.51 % of the total species richness. Fifty-four species were exclusive of fluvial sites (Fl), 39 of swampy sites (Sw), and 11 species of sandy sites (Sa); Fl and Sw shared 79 species, Sa and Sw shared 18 species, whilst Sa and Fl shared only seven species (Figure 2). Notably, 146 species occurred in all three habitat types.

Figure 2 Venn diagram showing the distribution of species richness among the three habitat types. Each circle represents a habitat type (Fl, Fluvial; Sw, Swampy; Sa, Sandy).

Overall, the most species-rich genera were Carex (11 species), Juncus (10), Ranunculus (10), Trifolium (9), Vicia (5), Cyperus (4), Euphorbia (4), Plantago (4), Persicaria (4) and Silene (4), accounting together for 18.36 % of all species. Amongst the inventoried species only 13 (3 %) were endemic to North Africa, and two species were endemic to the study region (Hypericum afrum (Desf.) Lam. and Solenopsis laurentia (L.) C. Presl.).

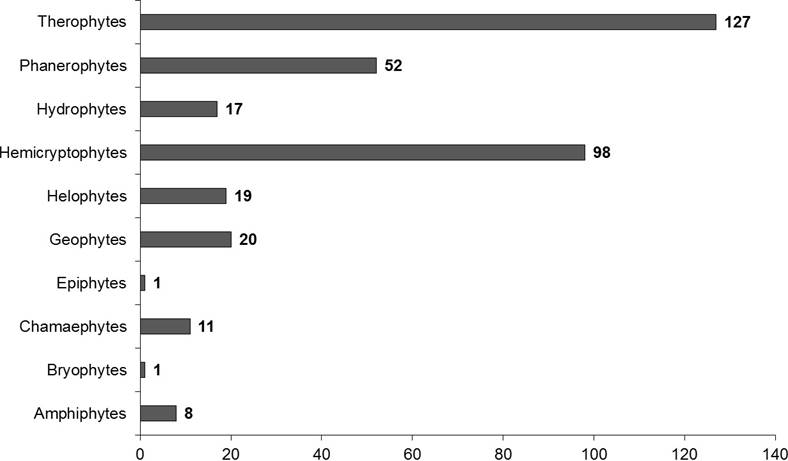

Life form distribution. Therophytes were the most common life form (127 species, 35.88 %), while 98 species (27.68 %) were Hemicryptophytes, 52 (14.69 %) Phanerophytes, 20 (5.65 %) Geophytes, 19 (5.37 %) Helophytes, 17 (4.80 %) Hydrophytes, 11 (3.11 %) Chamaephytes, and 8 (2.26 %) were Amphiphytes (Figure 3). Bryophytes and Epiphytes were represented by one species only.

Figure 3 Life form frequency distribution in the flora recorded in the El-Kala Biosphere Reserve, norteastern Algeria.

Diversity and similarity. Species rarefaction curves revealed that the mean observed species richness was highest in fluvial and swampy sites, in contrast with sandy sites (Figure 4a), with 285, 282 and 182 species, respectively (Table 1). There was a strong overlap between fluvial and swampy sites, whilst sandy sites stood out for not having any floristic overlap with the other habitat types (Figure 4A, Table 1).

Figure 4 A. Sample-based rarefaction and extrapolation for plant species richness. B. Sample coverage as a function of sample size. C. Coverage-based rarefaction and extrapolation for plant species richness. Number of sampling units indicates the cumulative number of plots. Continuous and discontinuous lines in all panels represent rarefaction and extrapolation, respectively; the shaded areas represent the 95 % confidence interval. Fl, Fluvial sites; Sw, Swampy sites; Sa, Sandy sites.

Table 1 Summary of plant diversity at each habitat type (Fl = Fluvial; Sw = Swampy; Sa = Sandy, CI = Confidence interval, SD = Standard deviation).

| Fl | Sw | Sa | |

|---|---|---|---|

| S(est) Mean ± SD | 285 ± 5.85 | 282 ± 8.94 | 182 ± 7.59 |

| 95% CI Lower Bound | 273.54 | 264.48 | 167.12 |

| 95% CI Upper Bound | 296.46 | 299.52 | 196.88 |

| Chao 2 Mean ± SD | 323.82 ± 11.77 | 393.47 ± 29.91 | 266.42 ± 25.25 |

| 95% CI Lower Bound | 306.7 | 348.48 | 229.57 |

| 95% CI Upper Bound | 354.44 | 468.9 | 331.84 |

| Jack 1 Mean ± SD | 355.58 ± 18.59 | 373.8 ± 19.75 | 251.17 ± 8.11 |

| Jack 2 Mean | 366.72 | 425.53 | 288.37 |

| Bootstrap Mean | 321.07 | 323.05 | 213.18 |

Figures 4B and 4C show that only four sampling units were necessary to reach 80 % of the estimated species richness for the sandy and swampy habitats, while five were required for the fluvial one.

The ordination based on species presence/absence achieved a stable two dimension solution (stress = 0.154) and enabled us to plot different habitats in a two-dimensional space (Figure 5). Sandy sites were quite homogeneous, concentrated together and visibly separated from the other habitats. Swampy sites were separated from the other habitats with high heterogeneity and some level of overlapping with the fluvial ones. Finally, fluvial sites were instead poorly clustered and scattered among the others (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Non-metric multidimensional scaling ordination (NMDS) biplot of habitat (color figures) and species (black dots). Fl, Fluvial sites; Sw, Swampy sites; Sa, Sandy sites.

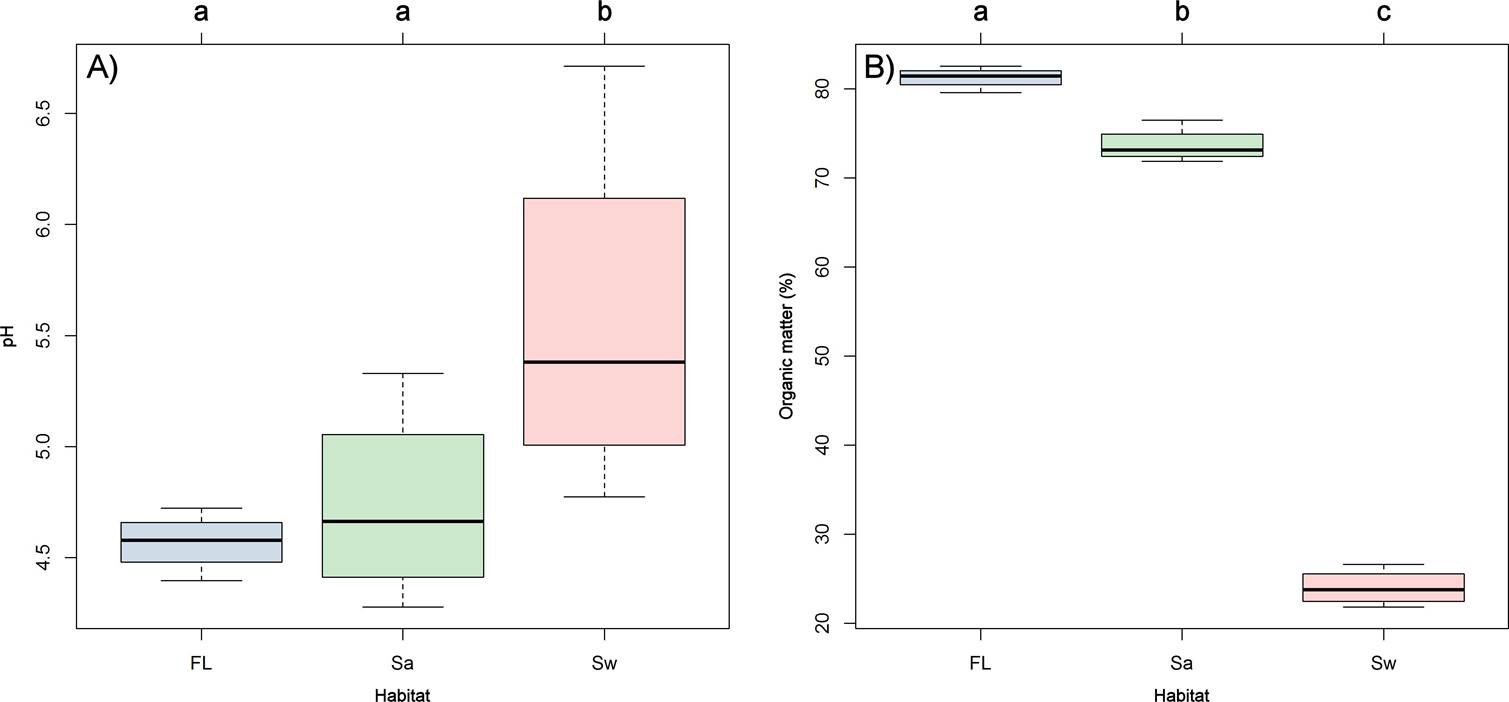

Relation of diversity to environmental factors. Variation in soil properties among the three habitat types was tested using Tukey contrasts for linear mixed models (LMMs). Soil pH differed significantly among habitat types (χ2 = 9.9941; df = 2; P = 0.006). Tukey tests revealed that soil pH differs significantly between swampy and fluvial sites, on one hand, and between swampy and sandy sites, on the other (Figure 6A). Soil organic matter (MO) was highly different among the three habitat types (χ2 = 2498.4; df = 2; P ˂ 0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that OM was highly different among the three habitat types (Fl-Sw, Sw-Sa, Fl-Sa; Figure 6B), in contrast with the other soil parameters, which showed homogeneity among habitats.

Figure 6 A. Box-plots of variation in pH and B. Organic matter (± 95 % CI) in the three sampled habitats. The letters indicate the statistical groupings (Tukey’s post-hoc tests); box-plots with the same letter are not significantly different.

Multiple linear regression analyses showed no linear relationships between species richness and soil parameters, except for OM (P = 0.013) (Table 2). ANOVA results confirmed this results, as significant variation in species richness was observed in relation to OM, but not with the four other parameters, namely pH, TL, EC, and PS (Table 3).

Table 2 Multiple linear regression models used to test the dependence of diversity variables on environmental variables.

| Diversity measure | Independent variables | Estimate | SE | t | F | R 2 adj |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species richness | EC | -17,577.715 | 21,592.463 | 0.424 | 0.08 | 0.180 |

| pH | -571.11 | 299.307 | 0.069 | |||

| TL | -134.385 | 166.441 | 0.428 | |||

| MO | -13.462 | 5.021 | 0.013 | |||

| PS | 43,944.74 | 48,410.323 | 0.373 |

Table 3 ANOVA results of the multiple linear regression

| Diversity measure | Independent variables | Mean ± SE | df | Sum sq | Mean sq | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species richness | EC | 0.491 ± 0.006 | 1 | 170 | 169.9 | 0.049 | 0.826 |

| pH | 4.95 ± 0.088 | 1 | 12,761 | 12,760.8 | 3.697 | 0.067 | |

| TL | 2.568 ± 0.072 | 1 | 35 | 34.9 | 0.010 | 0.920 | |

| MO | 59.187 ± 5.083 | 1 | 23,145 | 23,144.9 | 6.705 | 0.016 | |

| PS | 0.214 ± 0.003 | 1 | 2,844 | 2,844.4 | 0.824 | 0.373 | |

| Residuals | 22 | 75,941 | 3,451.9 |

Indicator species analysis. Ten plant species were highly (indicator value > 0.25) and significantly (P < 0.05) indicative of the three habitat types in the total dataset (Table 4). Among them, five were indicators of swampy sites, three more were indicators of the sandy habitat, and only two species were indicators of fluvial sites.

Table 4 Plant species with a significant indicator value at El-Kala Biosphere Reserve, northeastern Algeria. Habitat type abbreviations as in Table 2.

| Species | Habitat type | Indicator value | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stellaria media | Fl | 0.416 | 0.009 |

| Rosa sempervirens | Fl | 0.416 | 0.014 |

| Cotula coronopifolia | Sw | 0.578 | 0.007 |

| Genista ferox | Sw | 0.469 | 0.013 |

| Anthoxanthum odoratum | Sw | 0.423 | 0.023 |

| Fumaria capreolata | Sw | 0.375 | 0.047 |

| Clematis cirrhosa | Sw | 0.300 | 0.043 |

| Vicia narbonensis | Sa | 0.476 | 0.017 |

| Dipsacus fullonum | Sa | 0.416 | 0.020 |

| Raphanus raphanistrum | Sa | 0.365 | 0.048 |

Discussion

Through this investigation, we were able to produce a substantial checklist of the vascular flora occurring in alder forests of KBR. This checklist contributes to our understanding of those species that can thrive in these forest type, which characteristically become flooded for a long time every year, thus representing one of the exceptional wetlands in North Africa.

According to Quézel (1978), the most diverse families represented in the Mediterranean North African flora are Poaceae, Fabaceae, Cyperaceae, Asteraceae, Juncaceae, Ranunculaceae, and Brassicaceae, and our results agree with this statement. However, a noticeable discrepancy arises when comparing our study with that of Ghahreman et al. (2006), conducted in the northeastern Mediterranean region (Caspian lowlands), in which they report Rosaceae, Papilionaceae, Asteraceae, Cyperaceae, Brassicaceae, Lamiaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Apiaceae, Ranunculaceae, Aspidiaceae, Polygonaceae, and Liliaceae as the families having the largest species richness. Moreover, in terms of genera our results also differ from those reported by the same study, in which Asteraceae (11 genera), Poaceae (10 genera), Rosaceae (9 genera), Lamiaceae (8 genera), Apiaceae (5 genera) and Liliaceae (5 genera) were reported to be the best-represented families, and Carex (9 species), Rubus (6), Cardamine (5), Ranunculus (5), Veronica (5), Polystichum (4), Dryopteris (3), Equisetum (3), Geranium (3), Poa (3), and Solanum (3) were listed as the most speciose genera in alder forests. In turn, Bensettiti (1995) stated that the high abundance of Poaceae and Cyperaceae in alder forests reflects the degradation of some parts of these habitats into marshy prairies.

The life form spectrum of the KBR flora, dominated by therophytes, characteristically reflects the influence of the Mediterranean bioclimate (Medjahdi et al. 2009). Raunkiaer (1934) defined the Mediterranean climate type as a ‘therophyte climate’ (as therophytes are plants that remain in the soil as seeds during a certain period, whereas the vegetative parts are annual). This definition is based on the fact that all species with this life form account for over 50 % of the Mediterranean flora (Raven 1971). This proposition of Raunkiaer was confirmed by Cain (1950) in California, and by Quézel (1978) in North Africa. Nonetheless, this generalization was refuted in Chile, the Cape Region of South Africa and South Western Australia, where therophytes are normally absent and only appear in the immediate post-fire periods or after abundant rains (Blondel & Aronson 1995). In northeastern Mediterranean alder forests (Caspian lowlands), Ghahreman et al. (2006) found that geophytes were the dominant life form, accounting for 30 % of studied flora, followed by phanerophytes (22 %), therophytes (21 %), hemicryptophytes (17 %), hydrophytes (9 %), and chamaephytes (1 %). Usually, the high incidence of therophytes in plant communities is a result of increasing aridity (Barbero et al. 1989), and as in the present study, therophytes were the most common life form; their ample presence can be attributed to the habitats characterized by seasonal immersion/flooding, which are favorable to the development of annual plants capable of germinating and growing faster under harsh conditions (Hammada et al. 2004). Therefore, and due to their low ecological requirements, therophytes inhabit numerous habitats types (Gomaa 2012). In addition, the therophyte life form represents the eventual phase of degradation in xeric habitats, as it is frequently linked to environmental perturbations by grazing (Quézel 2000). The high rate of hemicryptophytes in all habitats is typical for pasture flora (Vitasović-Kosić & Britvec 2007). In turn, the low percentage of chamaephytes in alder forests reflects the low light intensity in the understory and the occurrence of long flood periods in these habitats (Thomas 1975).

According to the NMDS results, we were able to classify our study sites into two major groups, namely the marshy and the hilly (swampy-sandy) black alder forests, and the fluvial forests, in relation to plant species richness. This result is not surprising since Thomas (1975) had already shown that this dichotomy is the result of differences in the length of the flood period (seven to twelve months for hilly and marshy forests, whilst inundation only occurs during the flood season in fluvial alder forests), water level and light intensity. The spatial arrangement of the vegetation in this type of wetlands is not accidental; rather, it is the result of the interaction of numerous ecological factors, including abiotic, biotic, or anthropogenic (Alvarez-Rogel et al. 2007, Minggagud & Yang 2013).

Soil supply levels are important variables for plant diversity and community structure. Some features of plant community organization, such as composition and diversity of plant functional types, also affect plant productivity, maintenance, and soil fertility (Tilman et al. 1996). Soil pH is a relevant factor for plant development; it affects nutrient availability, toxicity, and microbial activity, and it exerts a direct effect on the protoplasm of plant root cells (Larcher 1980, Marschner 1986). Gould & Walker (1999) found a correlation between plant richness and pH; in their model, species richness declined when soil pH was at its acidic and alkaline extremes, which may be related to the nutrient availability and toxicity. In acidic soils, Al3+, Cu2+, Fe3+, Mn2+ ions increase to toxic levels for the bulk of plant species (Wolf 2000). Alkaline soils (pH > 8) have a tendency to be poor in Zn, Fe, Cu, K and Mn (Marschner 1986). Different plant species may not be as adaptable and thus they could need a narrow range of pH to live (Leskiw 1998). There is evidence that forest soils must be somewhat acidic for the nutrient resource to be stable (Leskiw 1998); yet, this does not seem to be the case in the present study, as no significant relationship was found between soil pH and richness.

Our study revealed a significant effect of soil organic matter on species richness. Soil organic matter contributes to soil fertility by providing nutrients and increasing both cation exchange and water holding capacity (Brady & Weil 1999). Few species can tolerate nutrient deficiency (Austin 2002). As resource availability increases, more species can persist and henceforth species richness increases.

The study of the vegetation of black alder forests in KBR allowed us to produce a more complete inventory of the plant community, and to better understand the distribution of vegetation across the area, as well as to identify those factors that affect its zonation. For this ecosystem, our study revealed a vegetation of relatively high diversity that is related to the variation of soil parameters. Black alder forests of KBR are predominantly disturbed by human activities, especially those related to tourism and leisure (e.g., cutting, burning, draining and/or dumping), which explains the degradation state of the ecosystem. Hence, more conservation efforts focused on these habitats should be made, supplemented with quantitative studies, in order to reduce anthropic activities and their impacts on the El-Kala Biosphere Reserve.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)