Echeveria DC. is a genus in the Crassulaceae comprising approximately 140 species distributed in the New World, from Texas to Argentina with the highest diversity in the mountainous areas of southern Mexico (Moran 1967, Walther 1935, 1972, Kimnach 2003). It was split from Cotyledon by De Candolle in 1828 by including all New World species that have a lateral inflorescence. Since then, Echeveria has undergone few changes. Oliveranthus Rose and Urbinia Rose were two taxa segregated at the beginning of the last century (Britton & Rose 1903), however these genera were not approved by taxonomists. Berger (1930) considered Thompsonella and Dudleya Britton & Rose to be part of Echeveria, yet both genera were reestablished later (Clausen 1940, Moran 1951). In the last 50 years, the circumscription of Echeveria has remained unchanged and is divided into 17 series based on morphological and chromosomal evidence (Walther 1972, Kimnach 2003, Pilbeam 2008).

Plants of Echeveria have leaves arranged in rosettes, with variable type of inflorescence (lateral spike, raceme, cyme, scorpioid cyme or cincinnus, thyrsoid). Flowers have mostly expanded succulent erect sepals, and bright colored succulent petals connate at the base (Kimnach 2003). The main traits used to recognize the 17 series are type of pubescence on the aerial stems, type of inflorescences and shape and length of the corolla (Walther 1972). However, most of the series are poly- or paraphyletic according to recent phylogenies, retrieved in clades embedded with species from Cremnophila Rose, Graptopetalum Rose, Sedum L. sect. Pachysedum H. Jacobsen, and Thompsonella Britton & Rose (Carrillo-Reyes et al. 2008, 2009).

Pachyphytum Link, Klotzsch & Otto is another genus in Crassulaceae mostly endemic to central Mexico comprising 19 described species, with a distribution centered on the Mexican Plateau, extending from southern Tamaulipas to northern Michoacán (von Poellnitz 1937, Moran 1963, 1989, 1991, García-Ruiz et al. 1999, Brachet et al. 2006, Martínez-Peralta et al. 2010). Most of the species in this genus have been described from a single locality (von Poellnitz 1937, Moran 1989, 1991, Brachet et al. 2006). Species grow in xerophytic scrub or less commonly in oak forest, and on vertical rock cliffs. Plants are characterized by a rock-dwelling habit, the leaves are terete, greenish or purple, sometimes conspicuously glaucous-farinose, the inflorescence is axillar, a scorpioid cyme or cincinnus, with somewhat imbricate succulent bracts. The flowers are pendant or rarely erect, pentamerous, succulent erect and appressed sepals sometimes surpassing the corolla, petals usually connate at the base, variously colored (white, greenish or reddish, or with maculae at the apex), with ten free stamens alternate or epipetalous and five nectaries. The fruits are erect to spreading and the seeds are ovoid and reticulate (von Poellnitz 1937, Uhl & Moran 1973, Thiede 2003, Thiede & Eggli 2007). Nevertheless, most authors coincide in recognizing scorpioid cymes or cincinnus, very succulent leaves and bracts and a nectary scale on the inner face of petals as the most important characters for distinguishing this genus (von Poellnitz 1937, Moran 1963, García-Ruiz et al. 1999, Brachet et al. 2006, Thiede & Eggli 2007). These similarities have led some authors to suggest that Pachyphytum might be included in Echeveria and be recognized as a section of the latter (Thiede 2003), however species of Pachyphytum have been retrieved in phylogenies in a well supported monophyletic group separate from Echeveria (Carrillo-Reyes et al. 2009).

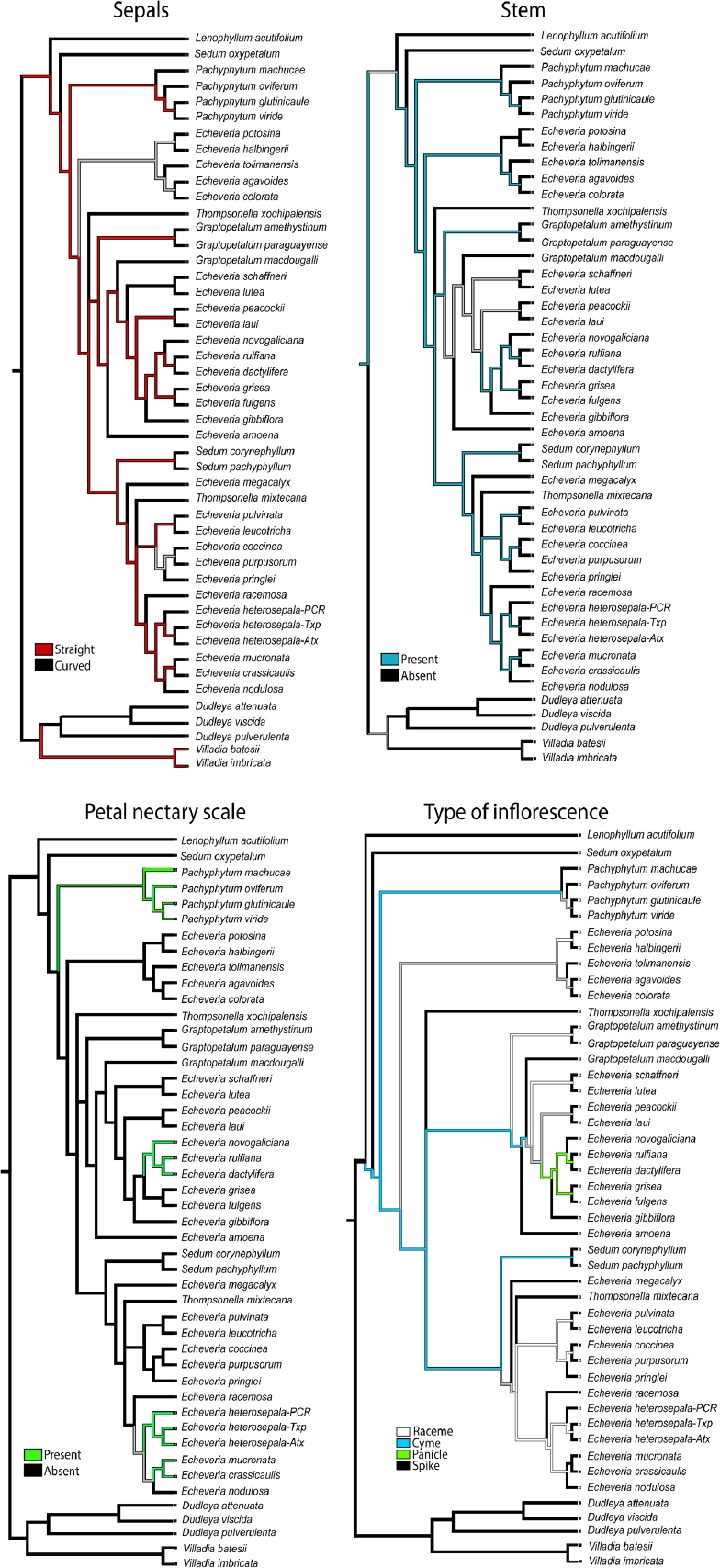

One of the rarest species with restricted distribution in Echeveria possesses a nectary scale on the inner face of the corolla elements: E. heterosepala Rose (Figures 1, 2). It has been either considered in Pachyphytum or in Echeveria with a complex taxonomic history exemplifying the inadequate delimitation of these genera in Crassulaceae and the lack of diagnostic characters to distinguish genera. E. heterosepala was described by Rose (Bull. New York Bot. Gard. 3: 8. 1930) and later this species was considered to be the monotypic section Echeveriopsis of Pachyphytum (Walther 1931). This change was reverted by Moran (1960) who returned the species to Echeveria, creating the monotypic section Chloranthae in Echeveria, because E. heterosepala has more in common with Echeveria than with Pachyphytum. E. heterosepala is a rare species collected only in two areas of xerophytic scrub vegetation in the south of the Mexican Plateau, one of the populations in the surroundings of the Atexcac lake (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Distribution of Echeveria heterosepala, triangles indicate the localities where this species was collected. Inflorescence, flowers, rosette and habitat of Lake Atexcac, Puebla (19° 20’ 1’’ N, 97° 27’’ 0’’) where it was collected are shown. The mountain chain Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt is shaded in green. Images taken by Pablo Carrillo at Atexcac, Puebla on March 26th, 2015.

Figure 2 Echeveria heterosepala. A) Rosette and lateral branch. B) Branch with scorpioid cyme or cincinnus. C) D) Petal nectary scale taken from the inner face of petals. E) Flower with all elements. F) Flower with petals removed showing ovaries and stamens. G) Detail of base of three stamens. Illustration hand drawn by Edmundo Saavedra.

Here we include Echeveria heterosepala in a molecular phylogeny to identify its position as well as to determine whether the nectary scale on the inner face of petals can be diagnostic for Pachyphytum. We include in analyses species of Echeveria, Graptopetalum Rose, Lenophyllum Rose, Pachyphytum, Thompsonella Britton & Rose and Villadia Rose that have been retrieved as closely related forming part of a clade known as the Acre Clade in the Crassulaceae (Carrillo-Reyes et al. 2009).

The objective of this paper is to identify the phylogenetic position of Echeveria heterosepala by means of molecular phylogenetic analyses and based on these results understand the evolution of the characters previously considered diagnostic for Echeveria and Pachyphytum.

Material and methods

Taxon sampling. We selected 47 taxa, representative species in the genera Echeveria (26 spp.), Graptopetalum (3 spp.), Lenophyllum (1 spp.), Pachyphytum (7 spp.), Thompsonella (2 spp.), Sedum (3 spp.) and Villadia (2 spp.) and based on previous phylogenetic analyses species in Dudleya (3 spp.) in the Leucosedum clade, were considered the outgroup (Carrillo-Reyes et al. 2008, 2009). Six Echeveria species with diagnostic characters attributed to Pachyphytum were included in the ingroup (E. novogaliciana, E. rulfiana, E. dactylifera, E. mucronata and E. crassicaulis) and E. heterosepala. Taxa, vouchers and GenBank accession numbers are listed in the Appendix 1.

DNA, extraction, amplification and sequencing. DNA was isolated using either a modified 2xCTAB method (Cota-Sánchez et al. 2006) or the DNeasy Plant MiniKit (Qiagen, Valencia, California) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Two plastid (rps16, trnL-F) and two nuclear regions (ETS, ITS) were sequenced. Amplification and sequencing primers for ETS were 18S-ETS (Baldwin & Markos 1998) and ETS-IGSF (Acevedo-Rosas et al. 2004); for ITS the primers were ITS4 and ITS5 (White et al. 1990); for rpS16, rpS16F and rpS16R (Shaw et al. 2005); and for trnL-F, trnL-c and trnL-f (Taberlet et al. 1991). PCR products were purified with QIAquick columns (Qiagen, Valencia, USA) or ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, USA), sequenced with the TaqBigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) and processed on a 310ABI DNA sequencer (Perkin Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA). The sequences were edited in Sequencher 5.4.6 (Gene Codes) and aligned by MUSCLE (Edgar 2004) followed by manual refinement using BioEdit (Hall 1999).

Phylogenetic analyses. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted independently for three datasets, ETS+ITS (nuclear data matrix), trnL-F and rps16 (plastid data set), and for the combined data matrix. First, jModelTest 2.1.6 (Darriba et al. 2012) was used to identify the model of molecular evolution that best fit the three different matrices; the best models were GTR+G+I, GTR+G and GTR respectively under the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic analyses were conducted with RAxML v7.0.4 (Stamakakis 2014). Clade support was assessed with 1,000 replicates of a nonparametric bootstrap analysis, also conducted with RAxML. Bayesian analyses were run in MrBayes v.3.2.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist 2001), for every run one cold and three heated chains were set to run for 40 million generations, sampling one tree every 2,000 generations. Stationarity was determined by the likelihood scores for time to convergence, and sample points collected prior to stationarity were eliminated (25 %). Posterior probabilities for clade support were determined by a 50 % majority-rule consensus of the trees retained after burn-in.

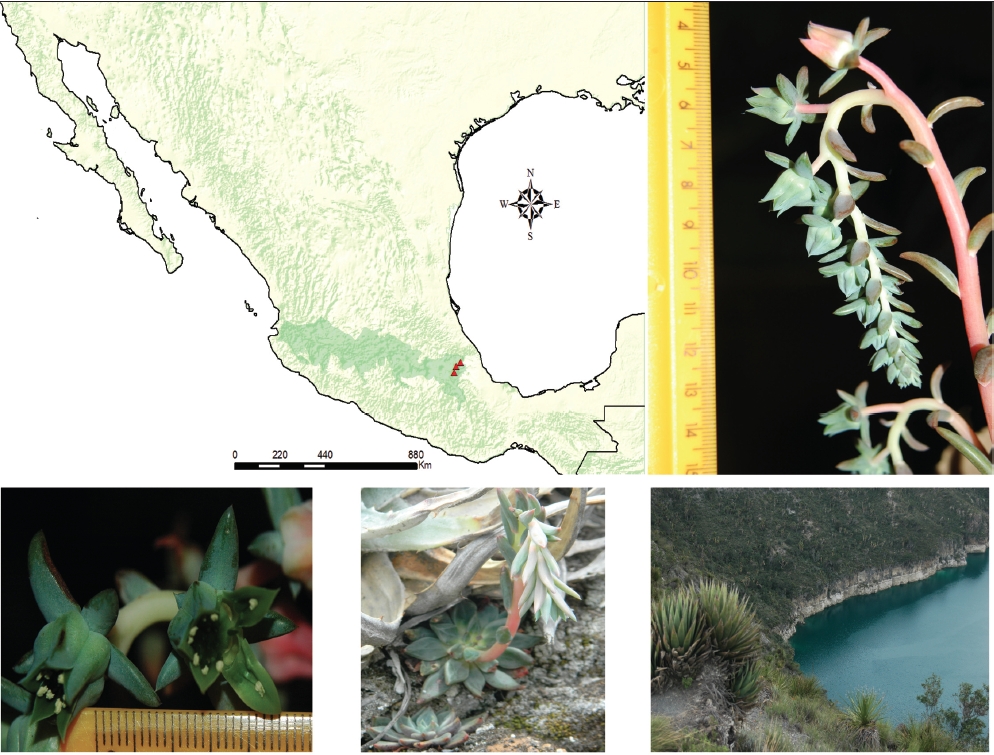

The trees retrieved by Bayesian inference based on the nuclear data, the most complete data matrix, were utilized to understand character evolution. Ancestral characters were inferred by the parsimony method, using the command trace character history and the unordered states assumption was selected for categorical characters using Mesquite v.2.75 (Maddison & Maddison 2017). This parsimony method finds the ancestral states that minimize the number of steps of character change given the tree and observed character distribution. The characters and character states analyzed were: 1) Sepals: straight/curved. 2) Stem: present/absent. 3) Petal nectary scale: present/absent. 4) Type of inflorescence: raceme/cyme/panicle/spike.

Results

Analyses with plastid and combined (plastid + nuclear) DNA data matrices were performed with a reduced number of terminals, restricting them to taxa with complete sequences. The plastid data matrix included 25 taxa and 1,461 bp with 67 parsimony informative characters while the combined data matrix included 21 taxa with 2,536 bp and 362 parsimony informative characters. ML and Bayes inference with plastid data retrieved unresolved trees in which only the clade formed by the three species of Dudleya, the outgroup, received support (not shown). The combined data matrix retrieved a well supported clade formed by species of Pachyphytum (bootstrap bst = 100 % and posterior probabilities PP = 1), the two accessions of Echeveria heterosepala with complete sequences formed part of a well supported clade (bst = 93 %, PP = 0.99) comprising species of Echeveria and Sedum dendroideum (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Fifty percent majority rule consensus Bayesian tree based on combined data matrices (plastid rps16+ trnL-F and nuclear ETS+ITS). Percentage of bootstrap of Maximum Likelihood is indicated above branches and posterior probabilities of Bayesian inference is indicated below branches. Maximum likelihood analyses were performed in RAxML v7.0.4 (Stamatakis 2014) and Bayesian inference in MrBayes v.3.2.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist 2001).

The most complete was the nuclear data matrix including 47 taxa with 1,090 bp and 372 parsimony informative characters (Figure 4). ML and Bayesian analyses based on this data matrix retrieved species of Pachyphytum in a well supported Clade I (bst = 100, PP = 1). This clade was sister to a large clade with the rest of the ingroup species (bst = 78 %, PP = 0.97), which in turn were divided into two groups: one of them, Clade II comprised exclusively of Echeveria species (bst = 100 % PP =1) and the remaining taxa were retrieved in Clade III (bst = 69 %, PP = 0.99) with species of Echeveria forming part of groups with Thompsonella, Graptopetalum and Sedum. Lenophyllum acutifolium was the sister group to the rest of ingroup species. Thre three accessions of E. heterosepala formed part of a clade with Echeveria species such as E. mucronata, E. crassicaulis, E. nodulosa and E. racemosa (bst = 96 %, PP = 1) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Fifty percent majority rule consensus Bayesian tree based on nuclear data matrix (ETS+ITS). Percentage of bootstrap of Maximum Likelihood is indicated above branches and posterior probabilities of Bayesian inference is indicated below branches. Maximum likelihood analyses were performed in RAxML v7.0.4 (Stamatakis 2014) and Bayesian inference in MrBayes v.3.2.2 (Huelsenbeck & Ronquist 2001).

From the reconstruction of ancestral character states under parsimony, the clade formed by the species of Pachyphytum identified that unambiguous ancestral character states were: stem present, straight petals and petal scaly bract present (Figure 5). For the rest of clades the character states were reconstructed as ambiguous for the four selected traits (Figure 5).

Discussion

Our study corroborated previous relationships identified by molecular phylogenies (Carrillo-Reyes et al. 2008, 2009): Pachyphytum was retrieved as a monophyletic group while species of Echeveria formed part of different clades with different genera. In this study we sequenced for the first time six species of Echeveria (E. heterosepala, E. novogaliciana, E. rulfiana, E. dactylifera, E. mucronata and E. crassicaulis) that have a nectary scale in petals, and based on previous sequences we selected seven species (E. halbingeri, E. colorata, E. tolimanensis, E. lutea, E. peacockii Baker, E. laui, E. purpusorum) with scorpioid cymes.

The only well supported clade formed exclusively by Echeveria species includes taxa of series Urbiniae: E. halbingeri, E. potosina, E. agavoides, E. colorata and E. tolimanensis, they share characters such as the lack of aerial stems and presence of urceolate flowers. Remarkably they do not share characters such like type of inflorescence. For example, E. tolimanensis, E. agavoides and E. colorata possess a cyme as inflorescence type while the rest of the species are characterized by a secund-racemose inflorescence.

The accessions of Echeveria heterosepala collected in Puebla, in Atexcac (Axc), Tenextepec (Txp) and Aljojuca (PCR) were retrieved in a well supported clade, closely related to species of Echeveria like E. mucronata, E. crassicaulis, E. nodulosa and E. racemosa. E. mucronata is an ornamental species with ample distribution from Arizona to Chiapas, E. crassicaulis grows along the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, E. nodulosa from Puebla and Oaxaca while E. racemosa has been recorded in Puebla and Veracruz. E. racemosa is the type species of ser. Racemosae (Walther 1972).

Since Pachyphytum was described as a separate genus from Echeveria, the most relevant diagnostic morphological character has been the presence of a petal nectary scale. Even so, this scale has been observed on a number of species of Echeveria, such as E. heterosepala (Walther 1972) thus raising uncertainty about the utility of this character as diagnostic for differentiating these genera. Although a number of species in Echeveria classified in different series possess the petal nectary scale (i.e. the diagnostic character used for Pachyphytum), Moran (1960), argued that species in Pachyphytum have morphological similarities and should be recognized as a different genus. Our results suggest that neither the petal nectary scale nor the rest of the characters are exclusive to Pachyphytum and, with exception of a well supported clade of Echeveria that corresponded to series Urbiniae, the rest of the species in this genus are embedded in clades with species in Thompsonella, Sedum and Graptopetalum. Our phylogenetic analyses found that E. heterosepala forms part of a clade comprised entirely by species of Echeveria, and in consequence this species belongs to Echeveria, not to Pachyphytum.

Our reconstruction of ancestral characters indicates that the scale on petals has arisen independently four times, in the clades of Pachyphytum, Echeveria novogaliciana, E. heterosepala and E. crassicaulis. The rest of the characters were reconstructed arising multiple times as shown in Figure 5. Petal elaborations, like the nectary scale, have been associated to diverse floral biological functions in angiosperms, mostly related to attracting pollinators (Endress & Matthews 2006). Ontogeny of nectary scale has been recorded only in two genera in Crassulaceae. In Pachyphytum the nectary scale resulted of petals having a ventral lobe and the petal is fused with the stamen of the same radius (Leinfellner 1954), while in Sedum the nectary scale potentially corresponds to a staminode (De Craene & Smets 2001). Probably different origin of nectary scale in petals of the different taxa studied here is the explanation for finding this character arising multiple times, and in consequence it cannot have taxonomic significance. However this hypothesis has to be tested.

Polyploidy has been reported in both Echeveria and Pachyphytum as well as in Graptopetalum, Lenophyllum and Sedum (see Table 1 and references herein). The basic chromosome number in the Acre clade is 10 and in the Leucosedum clade is 7 (Mort et al. 2001). All studied taxa in the Acre clade are polyploids, as well as the outgroup Dudleya that belongs to the Leucosedum clade. Excepting species of Graptopetalum with the highest known number of chromosomes in Crassulaceae, Pachyphytum hookeri is remarkable having reports of 160 chromosomes and moreover the rest of studied species in this genus have high numbers of chromosomes as well (see Table 1 and references herein). Polyploidy has been associated with complex evolutionary processes. For instance, it has been described that diploid and tetraploid plant species could be genetically differentiated but morphologically similar (Stark et al. 2011). Furthermore, polyploidy has been recognized as a mechanism for sympatric speciation (Otto & Whitton 2000) and it has been identified as well that speciation events in angiosperms can be accompanied by ploidy increase (Wood et al. 2009). Future studies may show whether polyploidy is the result of rapid speciation without morphological changes in the case of Pachyphytum and Echeveria or whether other causes correlated or not to polyploidy such like population isolation by the mountains of the Mexican Trans-Volcanic Belt promoted rapid speciation.

Table 1 Species considered in analyses for which there are chromosome counts.

| Species | Chromosome number | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Dudleya attenuata (S.Watson) Moran | 17 | Uhl & Moran 1953 |

| D. pulverulenta Britton & Rose | 17 | Uhl & Moran 1953 |

| D. viscida (S.Watson) Moran | 34 | Uhl & Moran 1953 |

| Echeveria amoena De Smet ex É.Morren | 33,66 | Uhl 1982, 1992 |

| E. coccinea (Cav.) DC. | 23,25 | Uhl 1963 |

| E. colorata E.Walther | 27 | Uhl 1982 |

| E. fulgens Lem. | 27,162 | Walther 1972 |

| E. gibbiflora DC. | 27,49, 51, 54 | Funamoto & Yuasa 1989 |

| E. grisea E.Walther | 27 | Uhl 1982 |

| E. megacalyx E.Walther | 20 | Uhl 1992b |

| E. nodulosa (Baker) Ed.Otto | 16 | Uhl 1961 |

| E. pringlei (S.Watson) Rose | 23 | Uhl 1992b |

| E. pulvinata Rose | 23+2 | Uhl 1992b |

| E. purpusorum A.Berger | 27 | Uhl 1982 |

| E. racemosa Cham. & Schltdl. | 18 | Uhl 1982 |

| Graptopetalum amethystinum E.Walther | 34,35 | Uhl 1970 |

| G. macdougallii Alexander | 64-66, 192, 244, 245 | Uhl 1970 |

| G. paraguayense (N.E.Br.) E.Walther | 68 | Uhl 1970 |

| Lenophyllum acutifolium Rose | 22,44 | Uhl 1996 |

| Pachyphytum glutinicaule Moran | 33, 66, 99 | Uhl & Moran, 1999 |

| P. hookeri A.Berger | 32, 64, ±128, ±160 | Uhl 2001 |

| P. kimnachii Moran | ±33 | Uhl & Moran, 1999 |

| P. oviferum J.A. Purpus | 33 | Uhl & Moran, 1999 |

| P. viride E.Walther | 33 | Uhl & Moran, 1999 |

| Sedum corynephyllum Fröd. | 34,68 | Uhl 1978 |

| S. oxypetalum Kunth. | 29 | Uhl 1980 |

| Sedum L. | 34 | Uhl 1978 |

The lack of definition of generic limits in Echeveria has already been identified based on molecular phylogenies (Mort et al. 2001, Carrillo-Reyes et al. 2009). To understand its limits, additional sampling of Sedum from Europe and Asia should be considered, as species in this genus appear embedded in Echeveria clades and mainly New World species have only been sequenced. Until now the Echeveria species included in analyses are mostly from Mexico; further collections from Central and South American need to be added. For Pachyphytum approximately ten species require to be considered as well. Novel primers for plastid genomes have been designed as an effective and feasible strategy for phylogenomics in many groups of angiosperms (Yang et al. 2014). Broader phylogenetic analyses should consider these primers for sequencing plastid data (current plastid markers utilized show little variation) and a more ample sampling. These analyses will help to finally understand limits not only of Echeveria and Sedum but also of Pachyphytum, to determine whether they should be split in several genera or not.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)