Tropical dry forests (TDF) are severely reduced in extension by human influence (Murphy & Lugo 1986, Janzen 1988, Gentry 1995). Miles et al. (2006) indicate that 97 % of their surface is threatened by the conversion to agricultural croplands; the increase of population density; the blazes caused by misuse of fires in agriculture; habitat fragmentation; and climate change. Likewise, Newton & Tejedor (2011) also consider the accelerated urbanization of these areas as a threat.

TDFs still cover 3,178,000 km2 across the world (Bezaury 2010); almost half is located in developing countries (UNDP 2004) and 8.8 % in Latin America and the Caribbean (Bezaury 2010). In this region, an important part of the inhabitants depends directly on environmental services of the forest. Weather and soil fertility of these areas also offer proper conditions for the development of several types of crops (Murphy & Lugo 1986). In Mexico, the presence of settlements in TDFs is related to the process of domestication of many food and medicinal plant species (Argueta 1994, Casas et al. 1994, Challenger 1998, Hernández-X 1998, Soto 2010); for this reason, they play a unique role in the social and economic context. Estimates indicate that people living in this kind of forests use a great number of vegetation species for their benefit (Dorado et al. 2002, Guízar-Nolazco et al. 2010).

In Mexico, TDFs stand out for their floristic diversity (Lott et al. 1987, Gentry 1995); approximately 20 % of Mexican flora is present in this type of vegetation (Rzedowski 1991a). Besides their great number of endemism (Rzedowski 1991b), TDFs are characterized as the richest forests of the world (Bezaury 2010, Rzedowski & Calderón 2013). Unfortunately, deforestation and fragmentation caused by agriculture contribute to their degradation (Rzedowski & Calderón 1987, Trejo & Dirzo 2000, Trejo 2010), as well as other less known social and environmental threats.

Regardless of the importance for the conservation of biodiversity and for the environmental services that sustain a considerable part of Mexico’s rural population (Toledo et al. 1989, Toledo & Ordoñez 1998, Dorado et al. 2002), the knowledge of the floristic, vegetation structure and composition, their current situation and change dynamics, as well as of the forces that promote their degradation is limited (Trejo 1998, 2010, Cervantes et al. 2001, Quesada et al. 2009). Although this tendency is changing, knowledge is focused only in few places of the country (Noguera et al. 2002, Gallardo-Cruz et al. 2005, Maass et al. 2005, 2010, Álvarez-Yépiz et al. 2008, Lebrija-Trejos et al. 2008) and reference to the causes of disturbance, when present, is superficial (Quesada et al. 2009).

It has been suggested that chronic disturbance in TDFs can have effects of similar magnitude to those of an acute disturbance (Singh 1998); hence, it is indispensable to recognize that these ecosystems are part of a matrix of humanized landscapes that are exposed to chronic disturbance. Thus, it is necessary to research on the causes of disturbance and the use forms of the human populations in the socio-ecological systems; this will help to ascertain the influence of management in the maintenance of the vegetation dynamics and to ponder the opportunities for conservation and restoration of these systems.

This paper approaches the analysis of the composition, structure and diversity of the TDF of the community of San Nicolás Zoyatlan. The investigation integrates: (1) a descriptive analysis of vegetation and the elaboration of a species list; (2) the relationship of the composition and structure of the vegetation with some environmental factors and the intensity of agricultural land use; and (3) the identification of species groups that may allow to ascertain the state and dynamics of the vegetation, as well as the potential for their use in restoration actions.

Materials and methods

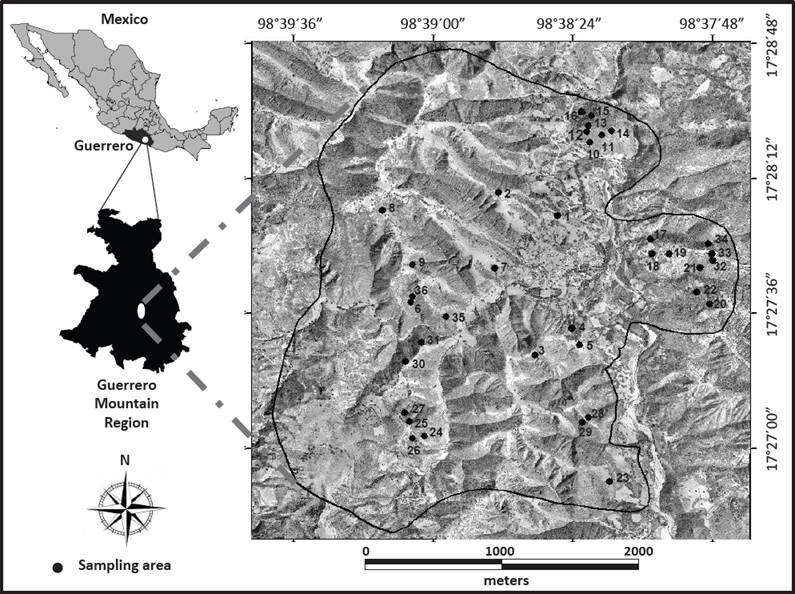

Research area. The rural community of San Nicolás Zoyatlan is part of Xalpatlahuac, one of 19 municipalities that shape the region called “La Montaña” in the State of Guerrero (Figure 1); this region is part of the Balsas watershed. The climate is semi-warm, sub-humid and annual average temperature is 27.5 °C with no frosts (García 1998). The rainy season occurs during summer, with average annual precipitation of 781 mm and a P/T ratio of 30.2. November to April is a period of water shortage, while the rainy season is from May to October. Zoyatlan covers an area of 924 hectares with a complex terrain characterized by altitudes ranging from 1,300 to 1,800 m a.s.l., a morphology of hills and summits in 83.62 % of the total surface, as well as slopes higher than 10° dominating 70 % of the landscape. Lithology is very diverse with materials of volcanic and sedimentary origin (Cervantes et al. 2014). Soils are shallow and rocky and are classified as Anthropic Regosol and Mollic Leptosol (Cervantes et al. 2005).

Figure 1 Location of the indigenous community of San Nicolás Zoyatlan, Gro. Mexico. The figure also shows the position of the fragments where vegetation sampling was done.

Zoyatlan has a long story of use of natural resources. The population is mostly of Nahua origin and the record of their settlements goes back to 1490 (Vega 1991). It is estimated that the factors that have contributed to the reduction of the vegetation cover in the territory are: transhumant flocks (which began with the Spanish conquest); the conflicts of land invasion at the beginning of the XX century and their negative impact both in the physical and biotic environment of the socio-ecological system, and in the disintegration of agricultural production systems (Cervantes & De Teresa 2004). In 1998 the main activities were subsistence farming, animal husbandry of goats, the collection of forest products and migration. Agriculture has been practiced with different intensities of land use and various agronomic practices (Cervantes et al. 2014) that are influenced by soil quality, water availability, landforms and socioeconomic aspects related with the production unit (Cervantes et al. 2005). Family ranching has been developed in fallow land and forest areas that belong to the owners of the herds. In 1998 the most important forestry activity carried out by the families in the community was firewood collection (Cervantes et al. 2014).

In 1998 Zoyatlan had 681 inhabitants organized in 116 families. That year, human settlements covered 3.17 % of the total area whereas agricultural use 25.9 %. Although 70.8 % of the surface had some type of woody vegetation of Juniperus forest, riparian forest, and TDF, their condition and cover was represented in scattered fragments. Considering its extent, TDF is the most represented vegetation type since it occupies 65.1 % of the total area. However, only two fragments with 8.08 ha were found in a moderately preserved condition; the remainder (591.72 ha) was represented by secondary TDF (Cervantes et al. 2014).

Vegetation sampling. With the use of the topographic map (1: 50,000; Xalpatlahuac E14D32) and aerial photographs (1: 80,000; 1979) 58 fragments with different vegetation cover (grassland, herbs, shrubs and trees of TDF) were initially identified. This information was verified during four field trips, and 36 fragments were selected with the following criteria: a) that the different vegetation types were distributed across the combinations of relief and lithology type; and b) that fragment size was ≥ 513 m2 (Figure 1).

Between June and November 1994, 12 plots of 3 × 3 m (108 m2 in total) were sampled and subplots were separated by 5 m between each other. In the higher right corner of each subplot, smaller plots of 1 × 2 m (24 m2 in total) were sampled. In each sampling area, physical environment factors -altitude, aspect, landform and slope- were recorded.

According to vegetation physiognomy, two layers were distinguished. Top layer (recorded in 3 × 3 m squares) included trees, shrubs, and succulent plants, with height ≥ 0.60 m. Species composition, percentage of cover per species, number of individuals per species and height were also recorded. Bottom layer included herbaceous plants and seedlings of other life forms: in 1 × 2 m squares species composition and percentage of cover per species was recorded and average height calculated. All species collected were pressed in the field and for taxonomic identification the specimens were matched in the herbariums of the Faculty of Sciences at UNAM, and MEXU; specialists for each taxonomic group were consulted.

Intensity of agricultural land use. To determine the use intensity of vegetation fragments, it was necessary to identify landowners. To this purpose, information from the genealogic inquiries done by Cervantes & De Teresa (2004) was used. In addition to this, research on the characterization of Zoyatlan production systems (Cervantes et al. 2005, 2014) was used to understand better the particularities of agricultural management in the area.

Data analysis. Vegetation data were processed using conventional methods (Mueller-Dombois & Ellenberg 1974, Matteucci & Colma 1982). Frequency and cover (absolute and relative) per fragment and species, as well as their importance value index (IVI = relative frequency specie i + relative cover specie i) were calculated for both layers. To describe physiognomy and the effect of use in stratification, height data in the top layer was separated in two ranges (≤ 2 m; and > 2 m). For the analysis of diversity, species richness (S), diversity index of Shannon-Wiener log2 (H’) and Simpson index (D) as a measure of dominance (λ = ∑pi2), were obtained.

To identify the formation of groups of species composition between the fragments, the method of non-hierarchical K-means clustering (Afifi & Clark 1997) was used. This analysis was based on the average percentage cover values per species —only from those species in the top and bottom layers that were present in four or more fragments—. To confirm the existence of significant differences between the groups, analysis of variance (ANOVA) were applied with the groups as an independent variable, and the Euclidean distances between and within groups (obtained in the analysis of K-means) as the dependent variable.

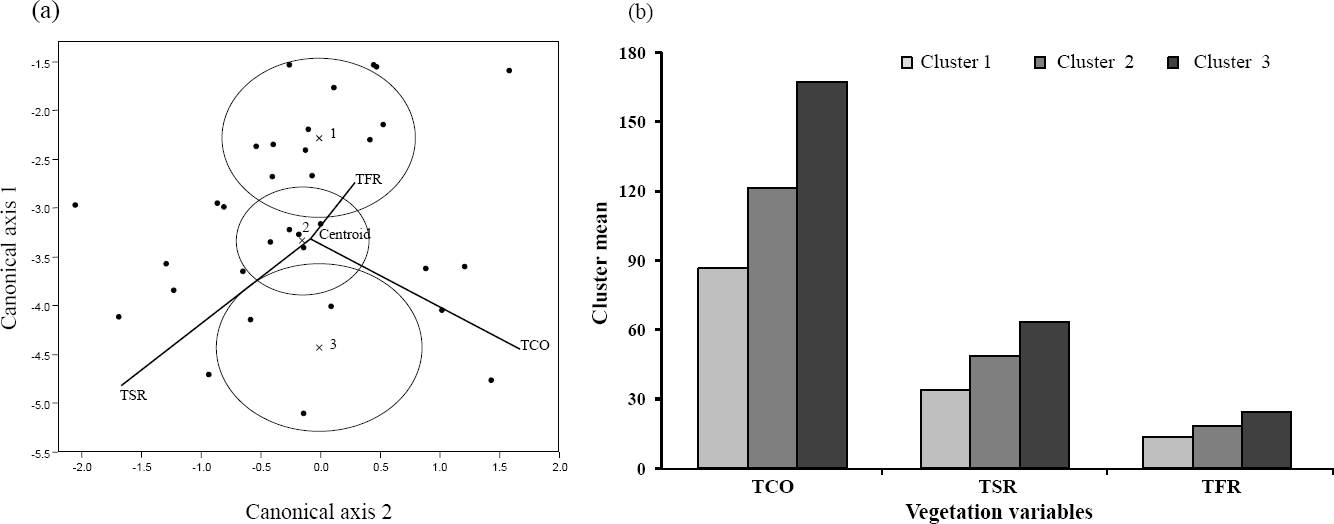

To explore the relationship between environmental factors of the fragments and vegetation variables, regression analyses (Montgomery 1991) were made relating altitude, lithology, aspect and slope with total cover (TCO) and total richness of species (TSR) and families (TFR). Where a statistically significant relationship was found, variables and factors were selected for a cluster analysis using Ward’s hierarchical clustering technique (Everitt & Dunn 1991, Johnson 2000). Subsequently, univariate or multivariate variance analysis (ANOVA or MANOVA) were applied to identify significant differences between the groups formed by the classification analysis. In both cases, groups obtained by the method of Ward were used as independent variables, and the vegetation or environmental factors as dependent variables. To display the formation of the groups that differed statistically, biplots (canonical centroid plot; SAS 1989) were made in a two-dimensional canonical space.

Results

Floristic composition. The floristic list of Zoyatlan includes 316 morphospecies (hereinafter species; Appendix 1) located predominantly in the Magnoliopsida class. Almost all specimens (except 5.06 %) were determined to some taxonomic level: 94.94 % (300) to family; 88.29 % (279) to genus; and 74.68 % (236) to species. Overall, the samples include 59 families, 178 genera and 279 species (Table 1).

Table 1 Floristic composition in the community of San Nicolás Zoyatlan, Guerrero Mexico. Numbers in brackets indicate the number of taxa where the species could not be determined. No. FR = number of fragment.

| GROUP | FAMILIES | GENERA | SPECIES |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnoliophyta | |||

| Magnoliopsida | 45 | 145 | 202 (+ 34) |

| Liliopsida | 10 | 27 | 29 (+ 8) |

| Pinophyta | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Pteridophyta | |||

| Lycopodiopsida | 1 | 1 | 0 (+ 1) |

| Polypodiopsida | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| TOTAL | 59 | 178 | 236 (+ 43) |

| FAMILIES (5 or more species) | |||

| Magnoliopsida | Acanthaceae | 6 | 6 |

| Asteraceae | 35 | 55 | |

| Boraginaceae | 6 | 6 | |

| Burseraceae | 1 | 7 | |

| Convolvulaceae | 3 | 8 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | 5 | 14 | |

| Fabaceae | 29 | 57 | |

| Lamiaceae | 2 | 8 | |

| Malvaceae | 6 | 10 | |

| Rubiaceae | 3 | 6 | |

| Verbenaceae | 4 | 7 | |

| Liliopsida | Poaceae | 15 | 23 |

| GENERA (4 or more species) | |||

| Magnoliopsida | Asteraceae | Eupatorium | 5 |

| Burseraceae | Bursera | 7 | |

| Convolvulaceae | Ipomoea | 6 | |

| Euphorbiaceae | Euphorbia | 8 | |

| Fabaceae | Acacia | 4 | |

| Fabaceae | Dalea | 4 | |

| Fabaceae | Desmodium | 4 | |

| Fabaceae | Marina | 6 | |

| Lamiaceae | Salvia | 7 | |

| Malvaceae | Sida | 4 | |

| PRESENCE OF SPECIES IN FRAGMENTS | |||

| No. FR | No. SPECIES | PROPORTION (%) | |

| 1 | 89 | 29.47 | |

| 2 a 3 | 86 | 28.47 | |

| 4 a 8 | 67 | 22.18 | |

| 9 a 18 | 41 | 13.58 | |

| 19 a 27 | 14 | 4.64 | |

| 28 a 34 | 5 | 1.66 | |

From the 59 families, 29 were represented by a single species (Appendix 1); 12 of these families had five or more species and gather 64.61 % of total genera and 74.19 % of all species. The families that are best represented considering the number of genera and species are Asteraceae, Fabaceae and Poaceae. Only in 10 genera, four or more species were found (Table 1).

Although 59 species are shared between the two layers (215 were exclusive to the bottom and 26 species to the top layer; Appendix 1), none was found in all 36 sampling sites. More than half of the species were found in one to three fragments (Table 1) and only five species (1.66 %) were found in at least 80 % of the fragments (between 29 and 34 sampling sites): Bidens aurea and Sanvitalia procumbens (Asteraceae), Acacia cochliacantha (Fabaceae), Loeselia coerulea (Polemoniaceae) and Bouteloua curtipendula var. caespitosa (Poaceae) (Appendix 1).

Richness and diversity. The average species richness (± 1 SD) of all 36 fragments was 48.28 ± 18.52 (range: 11-93). For the bottom layer, values were distributed from 11 to 79 and for the top layer from 1 to 28 species (Table 2). Similar trends were established for Shannon diversity index, with values for the bottom layer ranging from 2.60 to 5.64 and for the higher from 0 to 3.99. In both layers there was a strong positive linear relationship between species richness and diversity index (bottom layer: R2 = 0.85, F = 192.24, p < 0.0001; top layer: R2 = 0.77, F = 97.68, p < 0.0001). With regard to Simpson’s index, values obtained indicate low dominance, with the exception of five fragments where the values for the top layer were ≥ 0.52 (Table 2).

Table 2 Environmental characteristics and species richness, diversity and dominance values for vegetation fragments (VF) studied in the community San Nicolás Zoyatlan, Gro. Mexico. LI = Lithology (QBR - Quartzitic breccia, VBR - Volcanic breccia, AND - Andesite, LAN - Limestone-Andesite, LIM - Limestone, SAC - Sandstones conglomerate, TUF - Tuff); AL = Altitude; SL = Slope; AS = Aspect (S - South, N - North, E - East, W - West); LF = Landform (H - Hillside, Ge - Gentle, St - Steep, VS - Very steep, ES - Extended Summit, Ter - Terrace); Sr = Species richness; H´= Shannon-Wiener Diversity Index log2; D = Simpson Index.

| VF | ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS | BOTTOM LAYER | TOP LAYER | TOTAL | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LI | AL (m a.s.l.) | SL (%) | AS | LF | Sr | H’ | D | Sr | H’ | D | Sr | ||||

| 1 | QBR | 1402 | 17.6 | SE | GeH | 23 | 2.79 | 0.28 | 0 | 23 | |||||

| 2 | QBR | 1520 | 0 a 4.4 | ES | 17 | 3.34 | 0.12 | 0 | 17 | ||||||

| 3 | QBR | 1515 | 33 | S | StH | 28 | 4.03 | 0.07 | 0 | 28 | |||||

| 4 | QBR | 1428 | 65 | N | VSH | 43 | 4.1 | 0.11 | 6 | 1.43 | 0.52 | 44 | |||

| 5 | VBR | 1453 | 0 a 10 | ES | 22 | 3.16 | 0.22 | 0 | 22 | ||||||

| 6 | QBR | 1420 | 50 | N | VSH | 50 | 4.42 | 0.09 | 14 | 2.58 | 0.27 | 56 | |||

| 7 | QBR | 1408 | 55 | SE | VSH | 48 | 4.85 | 0.04 | 18 | 3.32 | 0.12 | 59 | |||

| 8 | QBR | 1522 | 37.5 | SE | StH | 38 | 4.22 | 0.09 | 8 | 2.21 | 0.33 | 42 | |||

| 9 | QBR | 1470 | 45 | NE | VSH | 33 | 3.96 | 0.12 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 33 | |||

| 10 | AND | 1348 | 45 | S | VSH | 33 | 4.04 | 0.1 | 4 | 1.88 | 0.29 | 34 | |||

| 11 | AND | 1372 | 54 | SE | VSH | 48 | 4.5 | 0.07 | 6 | 1.23 | 0.63 | 49 | |||

| 12 | AND | 1410 | 80 | SE | VSH | 58 | 4.97 | 0.05 | 8 | 2.97 | 0.14 | 63 | |||

| 13 | AND | 1440 | 40 | S | StH | 44 | 4.39 | 0.09 | 11 | 2.44 | 0.28 | 49 | |||

| 14 | LAN | 1392 | 34 | E | StH | 61 | 4.97 | 0.05 | 19 | 3.43 | 0.13 | 71 | |||

| 15 | AND | 1380 | 55 | N | VSH | 53 | 4.48 | 0.07 | 15 | 2.9 | 0.18 | 63 | |||

| 16 | AND | 1365 | 60 | N | VSH | 63 | 5.23 | 0.04 | 16 | 3.38 | 0.12 | 71 | |||

| 17 | SAC | 1380 | 65 | NW | VSH | 59 | 4.76 | 0.07 | 12 | 2.76 | 0.22 | 65 | |||

| 18 | LIM | 1470 | 30 | W | StH | 37 | 4.52 | 0.06 | 14 | 3.29 | 0.12 | 46 | |||

| 19 | LIM | 1358 | 0 a 8 | ES | 22 | 3.37 | 0.16 | 7 | 2.2 | 0.26 | 27 | ||||

| 20 | LIM | 1452 | 13 | NW | Ter | 37 | 4.07 | 0.11 | 0 | 37 | |||||

| 21 | LIM | 1440 | 51 | S | VSH | 47 | 4.59 | 0.07 | 19 | 3.74 | 0.08 | 57 | |||

| 22 | LIM | 1440 | 35 | SW | Ter | 11 | 2.6 | 0.29 | 0 | 11 | |||||

| 23 | QBR | 1475 | 40 | E | StH | 37 | 4.33 | 0.07 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 37 | |||

| 24 | QBR | 1442 | 54 | NE | VSH | 50 | 4.77 | 0.05 | 10 | 2.87 | 0.19 | 56 | |||

| 25 | TUF | 1485 | 45 | NE | VSH | 40 | 4.01 | 0.11 | 5 | 2.32 | 0.2 | 44 | |||

| 26 | QBR | 1468 | 50 | SE | VSH | 46 | 4.27 | 0.11 | 15 | 2.8 | 0.23 | 50 | |||

| 27 | QBR | 1460 | 60 | NE | VSH | 79 | 5.48 | 0.03 | 27 | 3.85 | 0.11 | 86 | |||

| 28 | QBR | 1350 | 0 a 8 | ES | 25 | 4.1 | 0.07 | 3 | 1.54 | 0.35 | 27 | ||||

| 29 | QBR | 1490 | 70 | NE | VSH | 45 | 4.46 | 0.06 | 8 | 1.76 | 0.40 | 49 | |||

| 30 | QBR | 1460 | 16 | N | GeH | 52 | 4.36 | 0.12 | 14 | 2.65 | 0.29 | 60 | |||

| 31 | QBR | 1413 | 0 a 4 | Ter | 47 | 4.51 | 0.07 | 10 | 2.81 | 0.18 | 50 | ||||

| 32 | LIM | 1480 | 40.4 | S | StH | 45 | 4.51 | 0.07 | 11 | 2.13 | 0.35 | 48 | |||

| 33 | LIM | 1484 | 0 a 4 | ES | 41 | 3.88 | 0.17 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 41 | ||||

| 34 | LIM | 1468 | 40 | NE | StH | 79 | 5.64 | 0.03 | 28 | 3.99 | 0.08 | 93 | |||

| 35 | QBR | 1377 | 80 | NE | VSH | 52 | 4.97 | 0.04 | 21 | 3.73 | 0.1 | 60 | |||

| 36 | QBR | 1450 | 70 | NE | VSH | 64 | 4.88 | 0.06 | 17 | 3.28 | 0.13 | 70 | |||

Vegetation structure. The bottom layer was the only one well represented in all 36 fragments since for six of them, the top layer was absent and, in another four it was represented only by individuals ≤ 2 m high (Table 3).

Table 3 Average height of vegetation in bottom and top layers, number of individuals and species as well as importance value index (IVI) obtained in the fragments (FR) of San Nicolás Zoyatlan community, Gro. Mexico. Ind = individuals; Sp = species; No. = number. The number in parenthesis besides the IVI corresponds to the name of the species: (1) A. dentata, (2) S. amplexicaulis, (3) E. prostrata, (4) B. curtipendula var. caespitosa, (5) B. repens, (6) D. hegewischiana, (7) D. tagetiflora, (8) L. graveolens, (9) T. stans, (10) O. atropes, (11) I. arborescens, (12) B. copallifera, (13) A. pennatula, (14) A. bilimekii, (15) A. cochliacantha, (16) A. farnesiana, (17) J. flaccida.

| No. Fragment | Bottom layer | Top layer | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size class ≤ 2 m | Size class > 2 m | ||||||||||||

| Height (m) |

IVI (%) |

Height (m) |

Ind. (No.) |

Species (No.) |

IVI (%) |

Height (m) |

Ind. (No.) |

Species (No.) |

IVI (%) |

||||

| 1 | 0.120 | 99.20 (1) | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 2 | 0.124 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.161 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | ||||||

| 4 | 0.170 | 53.69 (2) | 0.95 | 21 | 5 | 3.83 | 38 | 1 | 139.89 (14) | ||||

| 5 | 0.717 | 89.08 (3) | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 6 | 0.172 | 1.17 | 32 | 12 | 4.21 | 39 | 3 | 93.66 (14) | |||||

| 7 | 0.212 | 1.35 | 168 | 13 | 3.48 | 44 | 11 | ||||||

| 8 | 0.242 | 0.97 | 174 | 8 | 108.20 (8) | 3.64 | 5 | 3 | |||||

| 9 | 0.129 | 61.74 (4) | 1.84 | 9 | 1 | 200.00 (9) | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 10 | 0.159 | 52.51 (4) | 0.75 | 4 | 3 | 75.71 (11), 62.86 (10) | 3.50 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| 11 | 0.190 | 1.58 | 26 | 5 | 157.10 (11) | 3.18 | 9 | 4 | |||||

| 12 | 0.163 | 0.99 | 29 | 7 | 51.81 (12) | 3.34 | 19 | 8 | |||||

| 13 | 0.123 | 51.66 (5) | 0.83 | 37 | 11 | 91.15 (10) | 2.66 | 6 | 3 | ||||

| 14 | 0.195 | 0.99 | 83 | 18 | 3.04 | 16 | 6 | ||||||

| 15 | 0.153 | 0.68 | 44 | 14 | 52.20 (13) | 2.60 | 6 | 5 | |||||

| 16 | 0.171 | 1.10 | 66 | 15 | 3.63 | 19 | 7 | ||||||

| 17 | 0.125 | 1.09 | 55 | 12 | 3.08 | 18 | 3 | 85.55 (17) | |||||

| 18 | 0.178 | 1.18 | 131 | 12 | 3.60 | 10 | 4 | ||||||

| 19 | 0.800 | 70.77 (14) | 1.24 | 41 | 7 | 58.91 (14) | 2.23 | 4 | 2 | 74.26 (13) | |||

| 20 | 0.145 | 53.39 (3) | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 21 | 0.162 | 1.22 | 176 | 18 | 3.58 | 35 | 8 | ||||||

| 22 | 0.340 | 103.43 (6) | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 23 | 0.186 | 1.90 | 7 | 1 | 200.00 (14) | 3.00 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 24 | 0.152 | 0.82 | 15 | 9 | 3.50 | 1 | 1 | 75.37 (16) | |||||

| 25 | 0.149 | 51.20 (7) | 0.53 | 5 | 5 | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 26 | 0.174 | 62.30 (4) | 0.99 | 96 | 15 | 86.34 (8) | 3.12 | 8 | 3 | ||||

| 27 | 0.328 | 1.25 | 120 | 24 | 4.10 | 20 | 10 | ||||||

| 28 | 0.121 | 0.77 | 3 | 3 | 77.78 (14), 77.78 (9) | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| 29 | 0.201 | 1.21 | 24 | 6 | 56.07 (9) | 3.45 | 14 | 3 | 113.99 (14) | ||||

| 30 | 0.181 | 63.79 (4) | 0.87 | 35 | 12 | 3.31 | 12 | 3 | 103.98 (14) | ||||

| 31 | 0.177 | 0.95 | 36 | 9 | 58.88 (15) | 3.25 | 3 | 3 | |||||

| 32 | 0.144 | 1.20 | 48 | 10 | 3.38 | 41 | 2 | 111.82 (14) | |||||

| 33 | 0.111 | 80.52 (3) | 0.55 | 2 | 1 | 200.00 (14) | 0.00 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 34 | 0.253 | 1.27 | 82 | 25 | 3.46 | 35 | 11 | ||||||

| 35 | 0.321 | 1.22 | 316 | 16 | 3.20 | 44 | 14 | ||||||

| 36 | 0.171 | 0.92 | 157 | 15 | 3.22 | 21 | 6 | ||||||

| Mean | 0.174 | 1.08 | 65.00 | 10.24 | 3.33 | 18.04 | 4.85 | ||||||

| ± 1D.E. | 0.061 | 0.44 | 70.45 | 6.76 | 0.43 | 14.64 | 3.56 | ||||||

| Median | 0.010 | 1.09 | 37.00 | 10.00 | 3.36 | 15.00 | 3.00 | ||||||

Average height (± 1 SD) for the bottom layer was 0.174 ± 0.06 m (range: 0.07 to 0.34 m). For individuals in the top layer with size ≤ 2 m, height ranged from 0.53 to 1.90 m, with an average of 1.08 ± 0.45 m; in the case of those > 2 m this value was three times higher: 3.33 ± 0.43 m, with heights ranging from 2.23 to 4.21 m (Table 3).

Regarding the number of individuals in the two established height intervals, sharp contrast was found between and within the fragments. For ≤ 2 m, the mean value (± 1 SD) was 65 ± 70.45; the dispersion of the data with respect to the average value is due to the fact that the number of individuals between fragments ranged from 2 to 316; in the case of the > 2 m interval, this number was significantly lower: 18.04 ± 14.21, with variations ranging from 1 to 44 individuals (Table 3).

There are also differences in the cover values between fragments and layers (Figure 2). In the bottom layer it ranged from 42.8 to 108.6 %, but only in six fragments cover was > 90 %. In the top layer, the dominant tendency was of low cover values, although they ranged from 0.4 to 107.9 %. For individuals ≤ 2 m in height, cover was > 50 % only in three fragments; as for those > 2 m, this occurred in nine —for both cases, cover was > 100 % only in fragment 35—. Thus the total cover between all 36 fragments was very dissimilar (ranging from 51 to 304 %), although average total cover (± 1 SD) was 122.89 ± 54.39. Cover values close to 100 % were found in several places that did not had a top layer; in others, it was similar or slightly higher than 100 % even if there was a top layer. Total cover values above 200 % (Figure 2) were found in four fragments only (7, 27, 34 and 35); in these, there was a well-developed top layer in both height intervals; mostly in accordance with the highest values for number of individuals and species (Table 3).

Figure 2 Proportion of vegetation cover of the bottom layer (Bot Lay) and top layer (Top Lay) in the vegetation fragments studied in San Nicolás Zoyatlan, Gro. Mexico. Top Lay-1: includes individuals with heights ≤ 2 m; Top Lay-2: includes individuals with heights > 2 m.

The importance value index (IVI) showed very low values; only 17 species (6.09 %) had IVI ≥ 50 (1/4 of the expected value of the IVI = 200). However, only eight did so in at least two fragments (Table 3). In the bottom layer, species that stood out were Aldama dentata, Dyssodia tagetiflora, Simsia amplexicaulis (Asteraceae), Euphorbia prostrata (Euphorbiaceae), Dalea hegewischiana (Fabaceae), Bouteloua curtipendula var. caespitosa and B. repens (Poaceae). Outstanding species in the top layer were Acacia bilimekii, A. cochliacantha, A. farnesiana, A. pennatula (Fabaceae), Bursera copallifera (Burseraceae), Ipomoea arborescens (Convolvulaceae), Juniperus flaccida (Cupressaceae), Lippia graveolens (Verbenaceae), Opuntia atropes (Cactaceae) and Tecoma stans (Bignoniaceae).

Intensity of agricultural land use. From previous research on the history of use of the fragments, we could corroborate that all of them are or were used for agriculture. However, duration of the fallow periods is a distinctive variable that characterizes semi-intensive agricultural systems of Zoyatlan into four distinctive use type. Use1 (U-1) - agriculture with fallow periods of 1 to 4 years without residual woody vegetation (fragments 1, 2, 3, 5, 20, 22 ); Use2 (U-2) - agriculture with fallow periods of 1 to 4 years with residual woody vegetation (fragments 9, 10, 11, 15, 19, 23, 24, 25, 28, 31, 33); Use3 (U-3) - areas with fallow periods of 8 to 10 years (fragments 4, 6, 12, 13, 14, 16, 18, 26, 30); and Use4 (U-4) - areas with fallow periods of more than 10 years (fragments 7, 8, 17, 21, 27, 29, 32, 34, 35, 36).

Floristic composition clusters (FCC). Based on the analysis of K-means applied to species that were present in four or more vegetation fragments, three clusters for the two layers were identified (Table 4). In the bottom layer the count was of 120 species, and 51 (42.5 %) occurred in all three clusters (Appendix 1). Cluster-1 grouped 28 fragments including species that are shared by the three groups and other 69 species; from the latter 10 were unique to this group: Acacia pennatula, Aeschynomene americana, Dalea foliolosa, Indigofera jamaicensis (Fabaceae), Calea hypoleuca, Zinnia violacea (Asteraceae), Euphorbia hirta (Euphorbiaceae), Lantana camara (Verbenaceae), Ruellia hookeriana (Acanthaceae) and Sida angustifolia (Malvaceae). Clusters 2 and 3 grouped few fragments (5 and 3 respectively) and fewer species (91 and 69 respectively). Although species 40 and 18 are different to those that are shared by all three clusters, they are part of Cluster-1 (Appendix 1); perhaps this is why there were no significant differences among these clusters (Table 4).

Table 4 Clusters of the fragments for the K-means analysis in the floristic composition of the bottom and top layers, and for the cluster analysis of the slope and the vegetation variables: total species and family richness and total cover. Also, results are shown of the ANOVA for the K-means analysis (ID = initial distance and MD = maximum distance for the cluster formation) and for the cluster with slope and vegetation variables independently, as well as the MANOVA for the combination of these variables. The asterisk indicates significant differences with p < 0.05; different letters indicate significant differences between groups according to Tukey-Kramer multiple means comparison test. The marks in the number of fragments indicate the land use types: X = agriculture with fallow periods of 1 to 4 years without residual woody vegetation (U-1); X = agriculture with fallow periods of 1 to 4 years with residual woody vegetation (U-2); X* = areas with fallow periods of 8 to 10 years (U-3); X• = areas with fallow periods of more than 10 years (U-4).

| GROUP | NUMBER OF FRAGMENT K-Means |

F | p | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOTTOM LAYER | 2.649 | 0.085 | |||||||||||||||

| Cluster-1 | ID = 8.838 | MD = 14.682 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4* | 5 | 6* | 8• | 10 | 11 | 12* | 13* | 14* | 15 | 16* | 17• | |||

| 18* | 19 | 20 | 21• | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 28 | 29• | 30* | 31 | 36• | |||||

| Cluster-2 | ID = 8.838 | MD = 15.930 | |||||||||||||||

| 9 | 27• | 32• | 33 | 34• | |||||||||||||

| Cluster-3 | ID = 10.318 | MD = 16.693 | |||||||||||||||

| 7• | 26* | 35• | |||||||||||||||

| TOP LAYER | 6.566 | 0.004* | |||||||||||||||

| Cluster-1 | ID = 2.619 | MD = 9.159 | A | ||||||||||||||

| 7• | 8• | 17• | 35• | 36• | |||||||||||||

| Cluster-2 | ID = 0.018 | MD = 8.421 | |||||||||||||||

| 4* | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12* | 13* | 14* | 15 | 16* | 18* | 19 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26* | B | ||

| 28 | 29• | 30* | 31 | 32• | 33 | ||||||||||||

| Cluster-3 | ID = 4.264 | MD = 9.342 | A | ||||||||||||||

| 6* | 21• | 27• | 34• | ||||||||||||||

| Ward’s clustering | |||||||||||||||||

| Slope Factor | 141.041 | 0.0001* | |||||||||||||||

| Cluster-1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 19 | 20 | 28 | 30 | 31 | 33 | A | |||||||

| Cluster-2 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 18 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | B | |

| 25 | 26 | 32 | 34 | ||||||||||||||

| Cluster-3 | 4 | 12 | 16 | 17 | 27 | 29 | 35 | 36 | C | ||||||||

| Vegetation Variables | 47.497 | 0.0001* | |||||||||||||||

| Cluster-1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 19 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 25 | 28 | A | ||||

| Cluster-2 | 4* | 6* | 7• | 8• | 11 | 12* | 13* | 14* | 15 | 16* | 17• | 18* | 21• | 24 | 26* | B | |

| 29• | 30* | 31 | 32• | 33 | 36• | ||||||||||||

| Cluster-3 | 27• | 34• | 35• | C | |||||||||||||

| Slope Factor and Vegetation Variables | 8.205 | 0.0013* | |||||||||||||||

| Cluster-1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 18* | 19 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 28 | 33 | A | |||

| Cluster-2 | 4* | 8• | 11 | 12* | 13* | 15 | 24 | 25 | 26* | 29• | 30* | 31 | 32• | AB | |||

| Cluster-3 | 6* | 7• | 14* | 16* | 17• | 21• | 27• | 34• | 35• | 36• | B | ||||||

The top layer had 27 species and, although 21 (77.8 %) were common to all three clusters (Appendix 1); there were significant differences between clusters (Table 4). Cluster-2 differs statistically from Clusters 1 and 3; it stands out because it gathers 21 fragments and incorporates the 27 participant species, including two that only show up at this cluster: Bunchosia canescens (Malpighiaceae) and Cordia curassavica (Boraginaceae). Clusters 1 and 3 were not statistically different; the first brought together five fragments and the second four. Both clusters had 23 species; 21 common to all three clusters and two more in each case: Cluster-1 Heliocarpus velutinus (Malvaceae) and Tournefortia hirsutissima (Boraginaceae); Cluster-3 Lippia dulcis (Verbenaceae) and Mimosa polyantha (Fabaceae) (Appendix 1).

Vegetation and environmental factors. The relationship between lithology and aspect factors with vegetation variables was weak (Table 5). The slope factor showed a reliable relationship with total cover (TCO), total richness of species (TSR) and families (TFR); for altitude this was the case only for the last two variables, but the correlation coefficient was very low. On this basis, slope was chosen as the environmental factor of interest to be analyzed with vegetation. Three clusters of fragments were identified in the classification analysis, for slope as well as for all vegetation variables (TCO, TSR, TFR); in both cases the ANOVA or MANOVA showed the significant differences between clusters (Table 4).

Table 5 Results of regression analysis between environmental and vegetation variables of 36 fragments studied in the community of San Nicolás Zoyatlan, Gro. Mexico. STA = statistics, TCO = total cover; TSR = total species richness; TFR = total family richness.

| STA | TCO | TSR | TFR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Altitude | ||||

| R2 | 0.071 | 13.497 | 15.867 | |

| F | 2.612 | 5.305 | 6.412 | |

| p | 0.115 | 0.027* | 0.016* | |

| Lithology | ||||

| R2 | 0.095 | 0.159 | 0.109 | |

| F | 0.509 | 0.889 | 0.594 | |

| p | 0.796 | 0.516 | 0.732 | |

| Aspect | ||||

| R2 | 0.054 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |

| F | 1.929 | 0.002 | 0.005 | |

| p | 0.174 | 0.961 | 0.943 | |

| Slope | ||||

| R2 | 27.676 | 31.891 | 30.662 | |

| F | 13.010 | 15.920 | 15.035 | |

| p | 0.001* | 0.000* | 0.000* |

The differences in the slope clusters are clear: in Cluster-1 (9 fragments), the slope values were the lowest (2 to 17.6 %); in Cluster-3 (8 fragments) slopes were the most pronounced (60 to 80 %); and in Cluster-2 (19 fragments) values were intermediate (30 to 55 %) (Table 4).

Vegetation variables of Cluster-1 (12 fragments) has the lowest values for TCO (53.37 to 106 %), TSR (11 to 44 species) and TFR (6 to 14 families). In Cluster-3 (3 fragments) highest values concurred for TCO (207.7 to 304.4 %), TSR (60 to 93 species) and TFR (28 to 33 families). In Cluster-2 (21 fragments) values for TFR (17 to 26 families) were intermediate compared to the other two clusters (Table 4). Although this trend persisted for TSR and TCO, values similar to those included in the other two clusters occurred in fragments 14, 16 and 33 for the former parameter; and in fragments 7 and 24 for the latter.

Clusters obtained from the MANOVA that combined vegetation variables and slope clusters (Table 4) are represented by three centroids (Figure 3a). The first (13 fragments; Table 4) had the cluster mean with lowest values for the slope (range: 2-70 %), TSR, TFR and TCO (Figure 3b), while centroid-3 (10 fragments) has the highest mean values (slope range: 34-80 %). Intermediate mean values are found in the 12 fragments gathered at the centroid-2 (Figure 3b); it stands out that only the fragments included in centroids 1 and 3 differ statistically (Figure 3a, Table 4).

Discussion

Vegetation description. Due to insufficient botanical knowledge of Balsas basin (Fernández-Nava et al. 1998, Jimenez-Ramírez et al. 2003, Pineda-García et al. 2007, Bezaury 2010) and the scarcity of quantitative studies of vegetation structure (Ávila-Sánchez et al. 2010, Guízar-Nolasco et al. 2010) it is difficult to analyze the floristic data originated from the research in Zoyatlan under the light of other studies. However, in a first approximation we can say that the 236 species determined for Zoyatlan represent 6.28 % of the 4,442 known for the basin (Fernández-Nava et al. 1998). Based on studies about the flora of the mid and high Balsas of the state of Guerrero, we find that our records represent 23.43 % of the total of species known for the TDFs of the municipality of E. Neri, which ranks third in diversity for the whole country (Jiménez-Ramírez et al. 2003); for the zone of Papalutla our data represent 49.27 % (Martínez-Gordillo et al. 1997). Considering that this type of vegetation is most common in the Balsas, but also that it stands out for its high species richness and number of endemic species (Rzedowski, 1991b, Bezaury 2010, Rzedowski & Calderón 2013) these ratios give a good idea of the representativeness of the flora of Zoyatlan; both in relation to what is known for the subregions of the Balsas, as to the context of endemic species. According to Jiménez-Ramírez et al. (2003) and Rodríguez-Jiménez et al. (2005) there are seven species endemic to the TDFs of the Balsas of Guerrero: Acacia bilimekii, Colubrina macrocarpa, Hechtia mooreana, Lasianthaea crocea, L. helianthoides, Opuntia atropes and Rhus nelsonii.

The research area has 29 % of all families registered for Balsas basin (Fernández-Nava et al. 1998) and between 76 and 44 % of those reported in municipalities of the state of Guerrero that are part of the Balsas center (Jiménez-Ramírez et al. 2003, Ávila-Sánchez et al. 2010) and high subregions (Martínez-Gordillo et al. 1997, Guízar-Nolasco et al. 2010). These studies point to Fabaceae, Asteraceae and Poaceae as the richest in species; this is also the case in Zoyatlan. However, while these families gather 48.38 % of the total species, other families represented by ≥ 5 species were, in order of importance: Euphorbiaceae, Malvaceae, Convolvulaceae, Lamiaceae, Burseraceae, Verbenaceae, Acanthaceae, Boraginaceae and Rubiaceae. All these families, except Lamiaceae, are recognized as the most diverse in dry forests around the world (Gentry 1995, Trejo 1998, Pérez-García et al. 2001, Jiménez-Ramírez et al. 2003, Gallardo-Cruz et al. 2005). Also, although in Zoyatlan were listed 71.43 % of the genera that Rzedowski & Calderón (2013) stand out as those with the largest number of species in the TDFs of Mexico, only 10 of these genera presented ≥ 4 species; however, three of them, Dalea, Eupatorium and Salvia, are not included in that study.

The low floristic similarity that occurs between TDFs is a phenomenon described both in terms of different regions of Mexico (Trejo & Dirzo 2002, Rzedowski & Calderon 2013) and between “stands” in a micro-basin (Balvanera et al. 2002) or a hill (Gallardo-Cruz et al. 2009). Although those investigations took into account only species that make up the tree stratum, according to our results it is likely that the pattern will recur at different scales regardless of the layer considered. For example, in Zoyatlan 71.67 % of the species were recorded only in the bottom layer and 8.7 % exclusively in the top layer. However, species replacement in the 36 fragments was high because no species was found in all of them and very few (Acacia cochliacantha, Bidens aurea, Bouteloua curtipendula var. caespitosa, Loeselia coerulea and Sanvitalia procumbens) were found in more than 75 %. Also, 175 species (57.95 %) occurred only in 1 to 3 fragments, and of these, 64 % were present only in the bottom layer and 23.4 % were common to both layers. Unfortunately, few comparative inferences can be made because there are very few studies in TDFs that analyze the plant component of the bottom layer (Gallardo-Cruz et al. 2005, Quesada et al. 2009, Sagar et al. 2012).

Despite the recurrent land use in Zoyatlan for more than five centuries, in its flora we can still recognize trends that are common to TDFs of other areas of the Balsas and the rest of the country; however, five species present in over 75 % of the fragments are known to inhabit disturbed areas (Calderón & Rzedowski 2001). Four of these five species are part of the most diverse families; while members of Fabaceae are often associated with primary and secondary vegetation, Asteraceae and Poaceae are always related to secondary vegetation (Guízar-Nolazco et al. 2010, López-Sandoval et al. 2010, Rzedowski & Calderón 2013). In this way composition, richness and species diversity that was found between fragments and the strata of each fragment in Zoyatlan had a great variability. According to the ideas of Halffter & Moreno (2005) this variability is a typical attribute of secondary vegetation communities.

Vegetation and environmental factors. Despite the variety of environmental conditions of the fragments, only slope showed a positive relation with total richness of species (TSR) and families (TFR) and total cover (TCO). Studies in TDFs from different parts of Mexico, and at different scales, also report a low relationship of species richness and diversity with environmental factors such as altitude, lithology and aspect (Balvanera et al. 2002, Trejo & Dirzo 2002, Durán et al. 2006, Chaparro-Santiago 2016); however, this has not been the pattern in the case of slope. At both national and local level it has been found that these forests are best preserved in areas with shallow soils and steep slopes, usually > 20° (Aranguren-Becerra 1994, Trejo & Dirzo 2000, 2002). This trend also happens in Zoyatlan, since fragments of lesser slope but with most precarious conditions of all vegetation variables (TSR, TFR and TCO) concur in Cluster-1; on the contrary, Cluster-3 showed the best development of vegetation variables but steepest slopes (Figure 3b; Table 4). This phenomenon is not unique to TDFs; several sources report that areas less altered by human activities are those with less favorable soil, climate and access (Hoonay et al. 1999, Prach et al. 2001, Cousins & Eriksson 2002, Graae et al. 2003). In Zoyatlan slope influences the availability of land for the development of any productive activity, as well as the choice of the most promising type of use; for example, the intensity of agricultural land use (Cervantes et al. 2005).

Vegetation and intensity of agricultural land use. Analyses of succession in TDFs using chrono sequences point to inconsistencies between the fallow period and the increased complexity of vegetation, both in richness and diversity of species as in the structure. In this regard, some authors (Burgos & Maass 2004, Hernández-Oria 2007, Lebrija-Trejos et al. 2008, 2010, Álvarez-Yépis et al. 2008) suggest that this is common in places with ≤ 10 years of fallow. However, over time (usually > 20 years) the process is “stabilized” because the effect of agricultural use decreases; this is first revealed in the structure and later in the richness and diversity of species. Others (Van der Wal 1999, Kennard 2002, Cramer et al. 2008, Holz et al. 2009) argue that inconsistencies are influenced by the type of agricultural management prior to the abandonment, and by the characteristics of the physical and biotic environment of the fragments (soil conditions, distance to source of propagules, forms of dispersal of species, etc.).

As was indicated four uses derived from variants of semi-intensive agriculture systems were identified in the fragments. These variants played an essential role in the characteristics of vegetation because they alert about differences in vegetation structure of fragments (Table 3), as well as the way clusters result from the classification analysis (Table 4). For example, in Cluster-1 fragments are from areas with agriculture use (current and in fallow) and show lowest cluster values for slope and vegetation variables (Figure 3b). The six fragments with U-1 lacked the top layer, while in those of U-2 that layer was represented by few individuals and usually with heights ≤ 2 m. Furthermore, these fragments had 8 of the 17 species with IVI ≥ 50 (Table 3). In Cluster-3 all the fragments had at least 10 years without agricultural use (U-3 and U-4; Table 4) and matched with the highest mean cluster values (Figure 3b); in their vertical structure, density was well represented both in the range of ≤ 2 m height, as in the > 2 m range (Table 3).

Perhaps the fragments of Cluster-2, with an intermediate average cluster value not statistically different from the other two (Table 4; Figures 3a and b), represent the inconsistencies regarding time of abandonment of sites and vegetation features, because this cluster includes fragments with three types of uses: from agriculture with residual vegetation (U-2) to nonagricultural use for over 10 years (U-4). Ten species of the top layer with IVI ≥ 50 were present in these areas, often with individuals of both height layers; however, as expected in U-2, the number of individuals was usually lower (Table 3). The condition that Cluster-2 is statistically similar to Cluster-1 and Cluster-3, suggests the evolution of the succession process; it is possible that fragments of Cluster-2 exhibit the extremes of the fallow period. However, the influence of management previous to abandonment should also be taken into account —both in the agricultural process as in residual vegetation— since it’s characteristics can help or hinder regeneration (Cramer et al. 2008).

The influence of the intensity of agricultural use was also important in the floristic composition clusters (FCC) derived from K-means analysis. However, it was more evident in the top layer since there were no statistical differences between groups for the bottom layer (Table 4). Perhaps the exclusion of species whose presence among fragments was sporadic (1-3 fragments) contributed to this situation because, although this applied to both layers, for the top layer, exclusion of species was only 12.6 % (22) and in the bottom layer it was 64 % (112). Thus, for the top layer Clusters 1 and 3 included almost all fragments (80 %) with more than 10 years without agricultural use and only one with U-3 (Table 4). As in the case of classification analysis, in Cluster-2 three types of use are present: all fragments with U-2, 90 % of those with U-3 and only 20 % with U-4. These proportions and significant differences in Cluster-2 with respect to Clusters 1 and 3, suggest that FCC of the top layer is a good indicator of the periods of fallow and the succession process.

Regarding the types of agricultural use of fragments and their relationship to 175 infrequent species, it stands out that a significant proportion (66.9 % = 117 species) was established in areas with a longer fallow period, U-3 and U-4. The remainder species are distributed almost equally in fragments with shorter fallow periods (16.6 % U-1 and U-2) and those (16.5 %) that inhabit sites with very different periods of fallow (namely with generalist habits). Surely, the high number of species in fragments with a longer fallow period is related to the development of a canopy that provides good vegetation cover. According to Sagar et al. (2012) cover in TDFs has an important effect on the species composition and diversity of the bottom layer, since it favors higher water retention, a decrease of water stress and an increase in productivity.

The peculiarities of the floristic composition of the fragments indicate that there is a species flow in the landscape of Zoyatlan. Taking into account the fallow periods and the behavior of species that are common to different layers, it turns out that this phenomenon happens when the parent species are present as well as where they are not part of the top layer; this process was evident also in the six fragments that did not have that layer (Appendix 2). In this dynamic 47 species belonging to 17 families were present, although Fabaceae, Asteraceae and Burseraceae were outstanding in providing the highest number of species. The flow that species showed between fragments suggests that the dynamics occur at different levels. On one hand, there are species steadily arriving to the fragments regardless their use type; in some cases even in spite of being represented as adults in only a few fragments. On the other hand, there are species that scarcely enter the fragments although there are adult individuals of them in at least five fragments (preferably in U-2 and U-3); furthermore, there is a minimum income of certain species exclusively in sites with U-4 (Appendix 2).

Negative impacts of fragmentation and chronic disturbance in population and landscape dynamics are diverse and act at different levels (Saunders et al. 1991, Singh 1998, Santos & Telleria 2006, Fisher & Lindenmayer 2007). While it might be expected that they could be evident in Zoyatlan due to fragmentation and chronic disturbance over more than five centuries, this was not conclusive because there are still many features in the vegetation that characterize the TDFs of the Balsas basin. The dynamics of vegetation regeneration, which has its best expression in fragments less suitable for the development of agriculture due to their inaccessibility was also evident; this suggests that agriculture and grazing has not exceed the threshold that would prevent the dynamics and reorganization of the socio-ecological system (Lunt & Spooner 2005, Cramer & Hobbs 2007). According to land use in 1998 (Cervantes et al. 2014) and the results of this research, the fragments with U-2, U-3 and U-4 are represented in nearly 600 ha. While this highlights the importance of the process at a landscape scale, the largest area occupied by shrubs and short trees (478 ha), suggests an impoverishment of the structure and composition of vegetation. However, the difference in the movement of species between fragments, points to species whose colonization habits lead the succession process, e.g., species of the genus Acacia, as well as those with specific requirements (U-3 and U-4) to ensure their establishment and development, e.g., species of the genus Lysiloma. All this is very useful for choosing species with the highest potential for environmental restoration actions; this was, in fact, the basic information for the establishment of plantations and agroforestry systems (Cervantes et al. 2001) that currently have successful results in Zoyatlan (Cervantes et al. 2014).

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)