Introduction

Invasive species have been considered one of the main causes of habitat degradation (Gurevitch & Padilla 2004) and highly related to global change and globalization (Kaluza et al. 2010). The result is an increase in the number of these species in different ecosystem around the planet, reaching areas that were almost inaccessible a few decades ago and even threatening protected plant communities (i.e. high altitudinal areas or riparian areas; Pauchard et al. 2009, Alexander et al. 2011, Aguiar & Ferreira 2013). Specific elements of globalization that explain the spread of invasive species around the planet are global change (global warming, nitrogen deposition or habitat fragmentation; Dukes & Mooney 1999) and also socieconomic ones, such as gross domestic product (GDP; Sharma et al. 2010), transport (Westphal et al. 2008) or tourism (Sutherst 2000) among others. Ultimately, the economic (Pimentel et al. 2005), health (Levine & D’Antonio 2003), and ecological (Lockwood & McKinney 2001, Reaser et al. 2007) consequences can be substantial. For some areas, rapid economic development has accelerated biological invasions (Lin et al. 2007). Hulme (2009) argues that the best strategy for invasive species control is to regulate the mechanisms that govern globalization rather than direct species-by-species management. Globalization as a recent phenomenon has been one of the most substantial drivers behind the homogenization of insular biotas (Florencio et al. 2013) related to worldwide alien species expansion (Levine & d’Antonio 2003, Westphal et al. 2008, Pyšek et al. 2010).

Islands are particularly sensitive to biological invasions (Hulme 2004, Silva & Smith 2004). Humans’ arrival with their accompanying species has been cited as the primary cause for ecosystems change (Atkinson & Cameron 1993). The tragic disappearance of native island biota and dismantling of island ecosystems worldwide have been primarily caused by the introduction of non-native species (Donlan & Wilcox 2008, Kueffer et al. 2010). In addition, mean temperature on the island of Tenerife has increased by around 0.6 degrees, while this increase has been almost 1.5 degrees in the case of minimum temperature (mean of nocturnal minima) in the last 70 years (Martín et al. 2012). The overall warming is milder than in the northern hemisphere, however, the more sensitive biota means that small changes can have a strong influence on community species composition.

As islands are considered more vulnerable to invasions, we analyse which parameters are best placed to explain the increase in introduced species, in terms of species richness and composition. We restricted the study to thermophile invasive and non-invasive introduced species, as they respond faster and are more closely related to climate change. We selected common socioeconomic parameters related to development, and also temperature anomalies detected in the archipelago. We analysed data going back to the 40s, as we have reliable information about these variables from this period onwards. The main hypotheses to test are whether mean and minimum temperature anomalies are the best variables to explain changes in species composition and richness of introduced and invasive species or whether other socioeconomic variables are more closely related to these changes. Base in the results we will suggest management proposals.

We consider that an interdisciplinary work involving economy, climate and ecology is required to understand the roles all these variable play in biological invasion and to provide a way forward in our understanding of the entire scenario of the process.

Material and methods

Study site. The Canary Island Archipelago is composed of seven islands, 100 km off Northwest Africa (28º N, 16º W). The islands exhibit a broad spectrum of habitats with marked altitudinal belts and islands of varied sizes. The highest island, Tenerife reaches 3,718 m a.s.l. and the lowest, Lanzarote, 800 m. Tenerife also occupies the largest (2.059 km2) and Hierro the smallest (273 km2) surface areas. The lower elevations exhibit a Mediterranean type climate, with cool, mild winters and warm, dry summers (< 300 mm of ppt/year). Mid-altitudes experience persistent cloud cover that maintains cool and humid summers, and colder winters with increased precipitation (>700 mm/year). Over 1,500 m a.s.l. the climate is more continental and arid, with cold winters and very hot summers (< 500 mm ppt/year). Island altitude has substantial influence on local climate, but in general, the Canary Islands are considered temperate-subtropical.

The islands are a densely populated territory with more than 2 million residents, a busy tourist destination, and well connected to transport routes for trade in goods and services. Furthermore, the Canary Islands have been identified as a location subjected to the consequences of climate change (Sperling et al. 2004, del Arco 2008, Brito 2008, Martín et al. 2012). The region’s biodiversity is characterized by its uniqueness with 3,857 endemic species among the 2,554 terrestrial plant taxa registered in the official biodiversity data bank of the Canarian Government (Arechavaleta-Hernández et al. 2010). However, 1,567 of these species have been introduced into the archipelago, reducing native flora endemicity (in percentages with respect the total) from fifty percent of the biota a few centuries ago to one third of the species today.

The geographical position of Canary Islands is commercially influenced by Europe, Africa, and America, climatically by the temperate and tropical bands to the north and south, and ecologically by continental and oceanic systems to the east and west, respectively. This makes the islands particularly suitable for studying the influences of climate and global interconnectedness in island biological composition.

Biotic information. Following the criteria employed by the Canary Islands’ biodiversity data-bank (Arechavaleta-Hernández et al. 2010), wild plant species (it does not include cultivate species, only does that dispersed without human assistance) were classified into the following three categories: native species, invasive and non-invasive introduced species. Native are endemic species of the archipelago and non-endemic but considered that reached the archipelago naturally (Arechavaleta-Hernández et al. 2010). From the last two groups, we selected only the thermophile species (defined as species whose original range of distribution is in warmer climates than the Canary Islands; Köppen & Geiger 1928), which tend to be the most sensitive species to climate change.

The method of assignment of the species to each decade has some limitations in as much as some of the plants could have arrived much earlier in the archipelago than the date they were detected in the field. Also, the species catalogue is base in published lists of species, and it is not taking into account the evolution of the species along the decades, they can be change from introduce to invasive (Dietz & Edwards 2006), but the period of time is short in order to consider important changes. In spite of that, the large amount of data allows the analysis and identification of relevant general patterns. We should consider this study as an exploratory analysis of relationships about this information and the variables used in the analyses, and that we consider is consistent with changes in the species composition.

Native taxa in the Canary Islands are defined as species that arrived via dispersal means not associated with anthropogenic activity (some of them have been able to evolve in situ and become endemic), such as species with restricted distribution, limited to one of the natural Canary Island habitats. If the accidental or deliberate introduction of a species into the Canary Islands is known, but the species has not extended its range throughout the islands to cause significant changes to ecosystems and native species, it is considered introduced non-invasive. Invasive species are characterized as being exotic species established in natural or semi-natural habitats, causing significant changes in ecological systems and native biota, with the potential for permanent disruption of the ecological continuity of the local environment. The total number of species included in the study were 41 invasive (hereafter invasive), 189 introduced non-invasive (hereafter introduced) and 477 native endemic (hereafter native).

All species were assigned to an appearance decade ranging from 1940 to 2010 (many of them were cited earlier, but these have been assigned to the 1940s’ decade), on the basis of collection dates cited in bibliographical records. This method has the disadvantage of being subject to an unknown delay after the actual arrival and appearance date of the species, and subsequent report and publication date. Consequently, the number of species reported in our study for the last decade is likely to be less than the actual number of species present on the islands. Information on the presence of the species is accumulative, meaning that if the species is present in one year, it is assumed present in subsequent decades unless extinction or eradication has been documented.

Socioeconomic and climatic information. The majority of information has been extracted from the Canarian Institute of Statistics (ISTAC; http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac), and the information has been grouped in decades to prepare the information for comparison with the biotic information.

The variables selected were number of tourists (before 1960 the information was extracted from Anonymous 1997; hereafter TOU), gross domestic product (before 1950 the information was obtained from Díaz 2003; hereafter GDP) and population density (hereafter POP). We took the value of the variables at the end of the decade, so 1940 took variable values from December 1949.

For mean temperature anomalies (hereafter TEM) and minimum temperature anomalies (hereafter mTEM), we used the information provided by Martín et al. (2012), using the average temperature anomalies for each decade. We consider that the average of the decade is more indicative than the value of the last year of the decade, in order to avoid the natural variability of the climatic information.

Statistical analyses. Ordination techniques help to explain community variation (Gauch 1982), and they can be used to evaluate trends over time as well as in space (Franklin et al., 1993, ter Braak & Šmilauer 1998). We used Detrended Correspondence Analysis (DCA; Hill & Gauch 1980, using CANOCO; ter Braak & Šmilauer 1998) to examine how species composition changed over time. Analyses were based on presence, and we analyzed the invasive, introduced and native species separately.

As a technique of direct gradient analysis, we used Canonical Correspondence Analysis (CCA; Hill & Gauch 1980) in CANOCO (ter Braak & Šmilauer 1998) to examine how species composition in different decades changed as a function of the independent matrix of information (TOU, GDP, POP, TEM and mTEM). We used a forward selection procedure to remove the variables that did not support a significant portion of the inertia reported by the analysis with a Monte Carlo permutation test (499 iterations for a p < 0.05) in CANOCO. Using this method we were able to estimate directly which variables were important to determine changes in species composition over these decades. Again, we proceeded by analyzing separately invasive, introduced and native species.

We correlated the site scores of the three DCA axis I and II with the five variables: TOU, GDP, POP, TEM and mTEM (using the Pearson correlation coefficient, for p < 0.05 and n = 7). Additionally, species richness of invasive, native and introduced was correlated with the indicated variables. For both analyses, we applied the Holm’s procedure for multiple testing.

Basic statistical methods followed those of Legendre & Legendre (1998) and were implemented using the SPSS statistical package (SPSS 1997).

Results

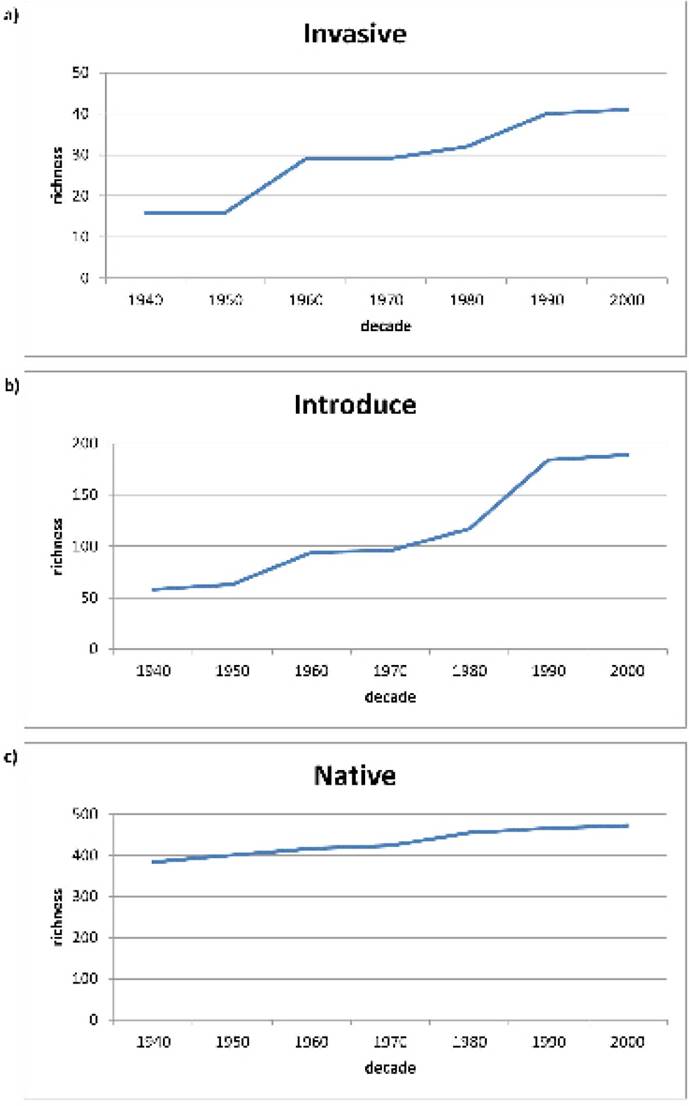

Values for richness of invasive, introduced and native species have been increasing over the last decades. This increase has been faster in the case of introduced (356 %) species followed by invasive (256 %) and finally endemic native species (130 %). Regarding invasive species, the fastest increase in richness is found between 1950 and1960; while for introduced ones the greatest rise was between 1980 and1990. For native endemic, the rate of increase in richness appears more continuous (Figure 1); Tables 1, 2 and Appendix 1 provide a list of the species included in the three groups: invasive, introduced and native species.

Figure 1 Species richness over decades for a) invasive thermophile b) introduced thermophile and c) native.

Table 1 Pooled list of invasive thermophilic species for the decade in which were cited for the first time as indicated in Arechevaleta-Hernández et al. (2010).

| Invasive exotic species | Decade | |

|---|---|---|

| Acacia farnesiana | (L.) Willd. | 1940 |

| Agave americana | L. | 1940 |

| Ageratina adenophora | (Spreng.) R. M. King & H. Rob. | 1940 |

| Ageratina riparia | (Regel) R. M. King & H. Rob. | 1940 |

| Anredera cordifolia | (Ten.) Steenis | 1940 |

| Argemone mexicana | L. | 1940 |

| Arundo donax | L. | 1940 |

| Datura innoxia | Mill. | 1940 |

| Datura stramonium | L. | 1940 |

| Eleusine indica | (L.) Gaertn. | 1940 |

| Lantana camara | L. | 1940 |

| Melinis repens | (Willd.) Zizka | 1940 |

| Nicotiana glauca | R. C. Graham | 1940 |

| Nicotiana paniculata | L. | 1940 |

| Opuntia maxima | Mill. | 1940 |

| Tropaeolum majus | L. | 1940 |

| Acacia cyanophylla | Lindl. | 1960 |

| Cardiospermum grandiflorum | Sw. | 1960 |

| Cyrtomium falcatum | (L.) C. Presl | 1960 |

| Ipomoea cairica | (L.) Sweet | 1960 |

| Mirabilis jalapa | L. | 1960 |

| Nassella neesiana | (Trin. & Rupr.) Barkworth | 1960 |

| Neurada procumbens | L. | 1960 |

| Opuntia dillenii | (Ker-Gawl.) Haw. | 1960 |

| Opuntia robusta | H.L. Wendland | 1960 |

| Opuntia tomentosa | Salm-Dyck | 1960 |

| Opuntia vulgaris | Mill. | 1960 |

| Pennisetum setaceum | (Forssk.) Chiov. | 1960 |

| Tradescantia fluminensis | Vell. | 1960 |

| Acacia dealbata | Link | 1980 |

| Caesalpinia spinosa | (Molina) Kuntze | 1980 |

| Ipomoea indica | (Burm. f.) Merr. | 1980 |

| Austrocylindropuntia exaltata | (Berg) Backeb. | 1990 |

| Furcraea foetida | (L.) Haw. | 1990 |

| Hylocereus undatus | (Haw.) Britton & Rose | 1990 |

| Ipomoea purpurea | (L.) Roth | 1990 |

| Kikoyuochloa clandestinum | (Vhiov.) H.Scholz | 1990 |

| Leucaena leucocephala | (Lam.) de Wit | 1990 |

| Maireana brevifolia | (R. Br.) P.G. Wilson | 1990 |

| Wigandia caracasana | Kunth | 1990 |

| Atriplex semilunaris | Aellen | 2000 |

Table 2 Pooled list of introduce thermophilic species for the decade in which were cited for the first time as indicated in Arechevaleta-Hernández et al. (2010).

| Introduce thermophilic species | Decade | |

|---|---|---|

| Abutilon grandifolium | (Willd.) Sweet | 1940 |

| Acacia farnesiana | (L.) Willd. | 1940 |

| Achyranthes aspera | L. | 1940 |

| Agave americana | L. | 1940 |

| Ageratina adenophora | (Spreng.) R. M. King & H. Rob. | 1940 |

| Ageratina riparia | (Regel) R. M. King & H. Rob. | 1940 |

| Alternanthera caracasana | “Humb., Bonpl. & Kunth“ | 1940 |

| Amaranthus deflexus | L. | 1940 |

| Amaranthus hybridus | L. | 1940 |

| Amaranthus lividus | L. | 1940 |

| Amaranthus muricatus | (Moq.) Hieron. | 1940 |

| Amaranthus viridis | L. | 1940 |

| Anredera cordifolia | (Ten.) Steenis | 1940 |

| Argemone mexicana | L. | 1940 |

| Arundo donax | L. | 1940 |

| Asclepias curassavica | L. | 1940 |

| Atriplex semibaccata | R. Br. | 1940 |

| Bidens pilosa | L. | 1940 |

| Caesalpinia sepiaria | Roxb. | 1940 |

| Calceolaria tripartita | Ruiz & Pav. | 1940 |

| Carthamus tinctorius | L. | 1940 |

| Ceratochloa catartica | (Vall) Herter | 1940 |

| Chamaesyce prostrata | (Aiton) Small | 1940 |

| Chenopodium ambrosioides | L. | 1940 |

| Colocasia esculenta | (L.) Schott | 1940 |

| Commelina benghalensis | L. | 1940 |

| Commelina diffusa | Burm. f. | 1940 |

| Conyza bonariensis | (L.) Cronquist | 1940 |

| Conyza floribunda | “Humb., Bonpl. & Kunth“ | 1940 |

| Conyza gouani | (L.) Willd. | 1940 |

| Cyperus rotundus | L. | 1940 |

| Datura innoxia | Mill. | 1940 |

| Datura stramonium | L. | 1940 |

| Einadia nutans | (R. Br.) A. J. Scott | 1940 |

| Eleusine indica | (L.) Gaertn. | 1940 |

| Hunnemannia fumariifolia | Sweet | 1940 |

| Lantana camara | L. | 1940 |

| Lepidium bonariense | L. | 1940 |

| Lepidium sativum | L. | 1940 |

| Lycopersicon esculentum | Mill. | 1940 |

| Malvastrum coromandelianum | (L.) Garcke | 1940 |

| Melianthus comosus | Vahl | 1940 |

| Melinis repens | (Willd.) Zizka | 1940 |

| Myrtus communis | L. | 1940 |

| Nicandra physalodes | (L.) Gaertn. | 1940 |

| Nicotiana alata | Link & Otto | 1940 |

| Nicotiana glauca | R. C. Graham | 1940 |

| Nicotiana paniculata | L. | 1940 |

| Nicotiana tabacum | L. | 1940 |

| Oenothera rosea | L`Hér. ex Aiton | 1940 |

| Opuntia maxima | Mill. | 1940 |

| Paspalum paspalodes | (Michx.) Scribn. | 1940 |

| Pennisetum villosum | R. Br. ex Fresen. | 1940 |

| Phylla nodiflora | (L.) E.L. Greene | 1940 |

| Physalis peruviana | L. | 1940 |

| Ricinus communis | L. | 1940 |

| Salvia coccinea | Juss. ex Murray | 1940 |

| Schinus molle | L. | 1940 |

| Scorpiurus muricatus | L. | 1940 |

| Senna bicapsularis | (L.) Roxb. | 1940 |

| Senna occidentalis | (L.) Link | 1940 |

| Sida acuta | Burm. f. | 1940 |

| Sida rhombifolia | L. | 1940 |

| Sigesbeckia orientalis | L. | 1940 |

| Solanum pseudocapsicum | L. | 1940 |

| Solanum robustum | H.L. Wendl. | 1940 |

| Soliva stolonifera | (Brot.) Sweet | 1940 |

| Sorghum halepense | (L.) Pers. | 1940 |

| Tagetes minuta | L. | 1940 |

| Tropaeolum majus | L. | 1940 |

| Turbina corymbosa | (L.) Raf. | 1940 |

| Verbena bonariensis | L. | 1940 |

| Waltheria indica | L. | 1940 |

| Xanthium spinosum | L. | 1940 |

| Casuarina equisetifolia | L. | 1950 |

| Cyperus involucratus | Rottb. | 1950 |

| Opuntia tuna | (L.) Mill. | 1950 |

| Salvia leucantha | Cav. | 1950 |

| Solanum marginatum | L. f. | 1950 |

| Acacia cyanophylla | Lindl. | 1960 |

| Adiantum raddianum | C. Presl | 1960 |

| Agave sisalana | (Engelm.) Perr. | 1960 |

| Amaranthus quitensis | “Humb., Bonpl. & Kunth“ | 1960 |

| Bidens aurea | (Dryand.) Sherff | 1960 |

| Cardiospermum grandiflorum | Sw. | 1960 |

| Chenopodium multifidum | L. | 1960 |

| Ciclospermum leptophyllum | (Pers.) Sprague | 1960 |

| Cotula australis | (Siebold ex Spreng.) Hook. f. | 1960 |

| Cucurbita pepo | L. | 1960 |

| Cyrtomium falcatum | (L.) C. Presl | 1960 |

| Erigeron karvinskianus | DC. | 1960 |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis | Dehnh. | 1960 |

| Galinsoga parviflora | Cav. | 1960 |

| Galinsoga quadriradiata | Ruiz & Pav. | 1960 |

| Guizotia abyssinica | (L. f.) Cass. | 1960 |

| Ipomoea cairica | (L.) Sweet | 1960 |

| Megathyrsus maximum | (Jacq.) B.K. Simon & S.W.L. Jacobs | 1960 |

| Melia azedarach | L. | 1960 |

| Mirabilis jalapa | L. | 1960 |

| Nassella neesiana | (Trin. & Rupr.) Barkworth | 1960 |

| Neurada procumbens | L. | 1960 |

| Oenothera jamesii | Torrey & A. Gray | 1960 |

| Opuntia dillenii | (Ker-Gawl.) Haw. | 1960 |

| Opuntia robusta | H.L. Wendland | 1960 |

| Opuntia tomentosa | Salm-Dyck | 1960 |

| Opuntia vulgaris | Mill. | 1960 |

| Oryza sativa | L. | 1960 |

| Oxalis corymbosa | DC. | 1960 |

| Oxalis latifolia | Kunth | 1960 |

| Pennisetum purpureum | Schumach. | 1960 |

| Pennisetum setaceum | (Forssk.) Chiov. | 1960 |

| Petunia parviflora | Juss. | 1960 |

| Phaseolus vulgaris | L. | 1960 |

| Salpichroa origanifolia | (Lam.) Baill. | 1960 |

| Sechium edule | (Jacq.) Sw. | 1960 |

| Sedum dendroideum | (Moq. & Sessé) ex DC. | 1960 |

| Selaginella kraussiana | (Kunze) A. Braun | 1960 |

| Solanum jasminoides | Paxton | 1960 |

| Stenotaphrum secundatum | (Walter) Kuntze | 1960 |

| Symphyotrichum squamatum | (Spreng.) G.L. Nesom | 1960 |

| Tagetes patula | L. | 1960 |

| Tradescantia fluminensis | Vell. | 1960 |

| Zebrina pendula | Schnizl. | 1960 |

| Ageratum houstonianum | Mill. | 1970 |

| Pennisetum thunbergii | Kunth | 1970 |

| Acacia dealbata | Link | 1980 |

| Adiantum hispidulum | Sw. | 1980 |

| Azolla filiculoides | Lam. | 1980 |

| Bougainvillea glabra | Choisy | 1980 |

| Bryophyllum delagoÎnse | (Eckl. & Zeyh.) Schinz | 1980 |

| Bryophyllum pinnatum | (Lam.) Oken | 1980 |

| Caesalpinia spinosa | (Molina) Kuntze | 1980 |

| Canna indica | L. | 1980 |

| Casuarina cunninghamiana | Miq. | 1980 |

| Catharanthus roseus | (L.) Don | 1980 |

| Commicarpus helenae | (Schult.) Meikle | 1980 |

| Eleusine tristachya | (Lam.) Lam. | 1980 |

| Fuchsia boliviana | Carrière | 1980 |

| Graptopetalum paraguayense | (N. E. Br.) E. Walther | 1980 |

| Hyparrhenia arrhenobasis | (Hochst. ex Steud.) Stapf | 1980 |

| Ipomoea indica | (Burm. f.) Merr. | 1980 |

| Iris albicans | Lange | 1980 |

| Leonotis nepetifolia | (L.) R. Br. in Aiton | 1980 |

| Maurandya scandens | (Cav.) Pers. | 1980 |

| Paspalum dilatatum | Poir. | 1980 |

| Paspalum urvillei | Steud. | 1980 |

| Pisum sativum | L. | 1980 |

| Senna didymobotrya | (Fresen.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | 1980 |

| Setcreasea pallida | Rose | 1980 |

| Agave ferox | C. Koch | 1990 |

| Agave fourcroydes | Lem. | 1990 |

| Alpinia zerumbet | (Pers.) Burtt & R. M. Sm. | 1990 |

| Amaranthus caudatus | L. | 1990 |

| Amaranthus cruentus | L. | 1990 |

| Amaranthus standleyanus | Parodi ex Covas | 1990 |

| Atriplex suberecta | Verd. | 1990 |

| Austrocylindropuntia cylindrica | (Lam.) Backeb. | 1990 |

| Austrocylindropuntia exaltata | (Berg) Backeb. | 1990 |

| Bambusa vulgaris | Schrad. | 1990 |

| Brugmansia suaveolens | (Willd.) Bercht. & J. Presl | 1990 |

| Bryophyllum daigremontianum | (Raym.-Hamet & Perr.) | 1990 |

| Bryophyllum proliferum | Bowie ex Curtis | 1990 |

| Calliandra tweedii | Benth. | 1990 |

| Calotropis procera | (Aiton) W. T. Aiton | 1990 |

| Cicer arietinum | L. | 1990 |

| Coffea arabica | L. | 1990 |

| Conyza sumatrensis | (Retz.) E.Walker | 1990 |

| Corchorus depressus | (L.) Stocks | 1990 |

| Cortaderia selloana | (Schult. & Schult. f.) Asch. & Graebn. | 1990 |

| Cyperus esculentus | L. | 1990 |

| Desmanthus virgatus | (L.) Willd. | 1990 |

| Euphorbia milii | Des Moul. ex Boiss. | 1990 |

| Fuchsia coccinea | Aiton | 1990 |

| Furcraea foetida | (L.) Haw. | 1990 |

| Gossypium herbaceum | L. | 1990 |

| Heliotropium curassavicum | L. | 1990 |

| Hylocereus undatus | (Haw.) Britton & Rose | 1990 |

| Hyparrhenia rufa | (Nees) Stapf in Prain | 1990 |

| Impatiens olivieri | C. H. Wright ex W. Watson | 1990 |

| Impatiens walleriana | Hook. f. | 1990 |

| Imperata cylindrica | (L.) Rauschel | 1990 |

| Ipomoea batatas | (L.) Lam. | 1990 |

| Ipomoea hederacea | Jacq. | 1990 |

| Ipomoea pes-caprae | (L.) Sweet | 1990 |

| Ipomoea purpurea | (L.) Roth | 1990 |

| Kikoyuochloa clandestinum | (Vhiov.) H.Scholz | 1990 |

| Leucaena leucocephala | (Lam.) de Wit | 1990 |

| Lippia canescens | “Humb., Bonpl. & Kunth“ | 1990 |

| Maireana brevifolia | (R. Br.) P.G. Wilson | 1990 |

| Montanoa bipinnatifida | (Kunth) C. Koch | 1990 |

| Musa acuminata | Colla | 1990 |

| Nephrolepis exaltata | (L.) Schott | 1990 |

| Oenothera striata | Ledeb. ex Link | 1990 |

| Oplismenus hirtellus | (L.) P. Beauv. | 1990 |

| Parkinsonia aculeata | L. | 1990 |

| Paspalum distichum | L. | 1990 |

| Passiflora suberosa | L. | 1990 |

| Phaedranthus buccinatorius | (DC.) Miers | 1990 |

| Phyllanthus tenellus | Roxb. | 1990 |

| Pistia stratiotes | L. | 1990 |

| Pteris cretica | L. | 1990 |

| Pteris multifida | Poir. | 1990 |

| Pyrostegia venusta | (Ker-Gawl.) Miers | 1990 |

| Saccharum officinarum | L. | 1990 |

| Salvinia natans | (L.) All. | 1990 |

| Sansevieria trifasciata | Prain | 1990 |

| Sedum mexicanum | Britton | 1990 |

| Senna corymbosa | (Lam.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | 1990 |

| Senna multiglandulosa | (Jacq.) H. S. Irwin & Barneby | 1990 |

| Sesuvium portulacastrum | (L.) L. | 1990 |

| Sidastrum paniculatum | (L.) Fryxell | 1990 |

| Simmondsia chinensis | (Link) C. K. Schneid. | 1990 |

| Solanum giganteum | Jacq. | 1990 |

| Solanum gracile | Otto | 1990 |

| Solanum mauritianum | Scop. | 1990 |

| Solanum microcarpum | (Pers.) Vahl | 1990 |

| Solanum nodiflorum | Jacq. | 1990 |

| Solanum tuberosum | L. | 1990 |

| Tithonia diversifolia | (Hemsl.) A. Gray | 1990 |

| Tradescantia blossfeldiana | Mildbr. | 1990 |

| Tripleurospermum inodorum | (L.) Sch. Bip. | 1990 |

| Wigandia caracasana | “Humb., Bonpl. & Kunth“ | 1990 |

| Xerochrysum bracteatum | (Vent.) Tzvelec | 1990 |

| Zea mays | L. | 1990 |

| Atriplex semilunaris | Aellen | 2000 |

| Gnaphalium antillanum | Urb. | 2000 |

| Nicotiana glutinosa | L. | 2000 |

| Portulaca nicaraguensis | (Danin & H. G. Baker) Danin | 2000 |

| Portulaca papillato-stellulata | (Danin & H. G. Baker) Danin | 2000 |

| Suaeda fruticosa | Forssk. ex J. F. Gmel. | 2000 |

The information for TOU, GDP, POP, TEM, mTEM is presented in Table 3. The dramatic increase in GDP is particularly important from the decades 1940 to 1960. This was the period in which the Spanish dictatorship began to open up the economy ending decades of autarchy. This was followed by the tourist boom that started in the 60s. While the main increase in tourist numbers appeared in the 80s, the largest population increase (25 %) was in the decade of the 90s. With regard to temperature anomalies, the greatest rise in temperature appears in the last decade, while a constant but almost insignificant increase was the common pattern in the previous decades. The change in average temperature is more relevant in the case of minimum temperatures.

Table 3 Socioeconomic and climatic information (GDP: Gross domestic product in millions €; POP: Resident population; TOU: Millions of tourists; TEM: mean temperature anomalies; mTEM: minimum mean temperature anomalies).

| Decade | GDP | POP | TOU | TEM | mTEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 44 | 813290 | 15 | -0.207 | -0.473 |

| 1950 | 1.801 | 974989 | 73 | -0.203 | -0.495 |

| 1960 | 5.264 | 1137599 | 792 | 0.151 | 0.010 |

| 1970 | 10.191 | 1388243 | 2228 | -0.155 | -0.292 |

| 1980 | 19142 | 1621710 | 5459 | 0.044 | 0.090 |

| 1990 | 32059 | 1767867 | 9975 | 0.077 | 0.179 |

| 2000 | 42097 | 2219846 | 8611 | 0.344 | 0.463 |

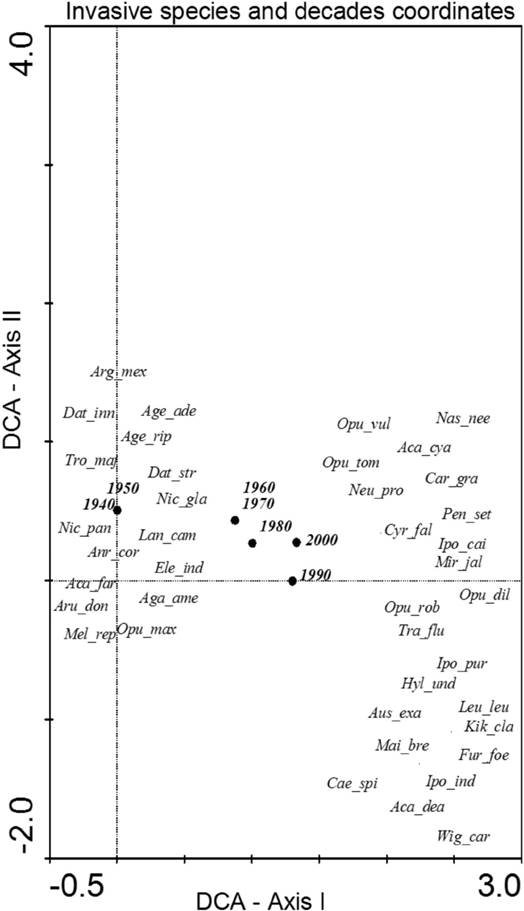

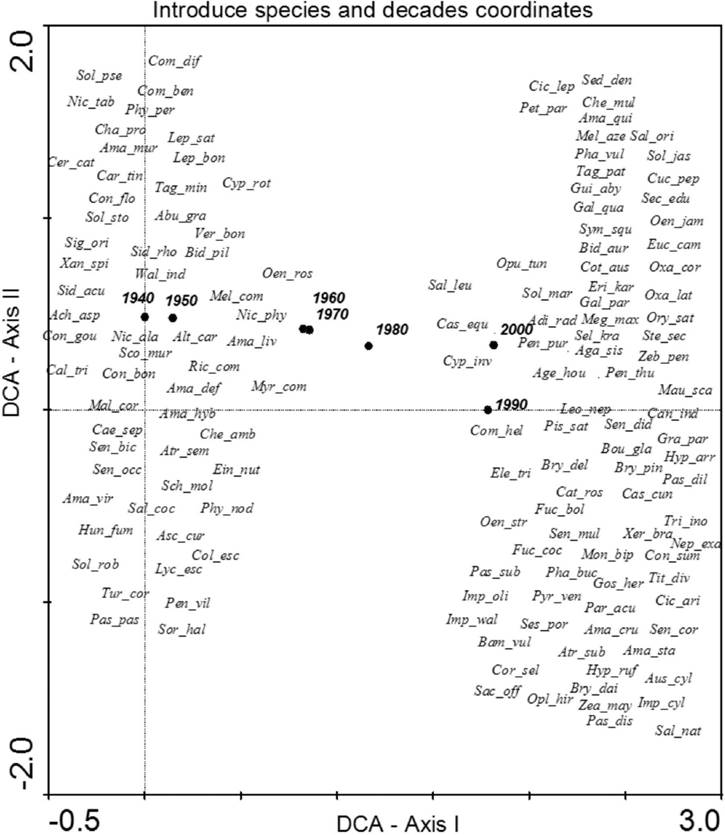

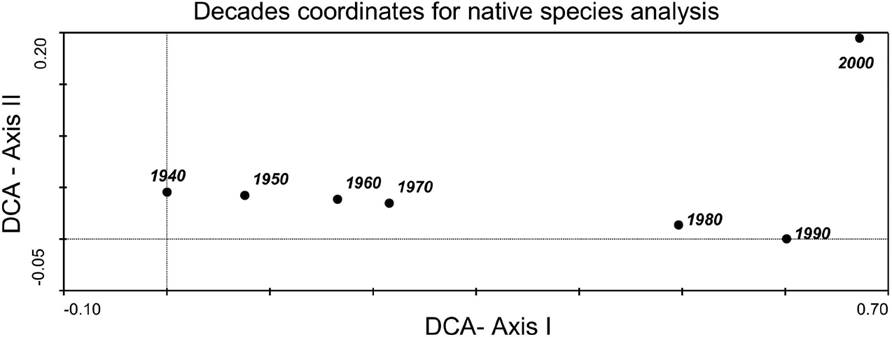

The analysis of species composition for invasive species revealed that a few of the most aggressive ones were present during the first decade of this study such as Opuntia maxima, Opuntia dillenii, Agave americana, Acacia farnesiana or Arundo donax; whereas others arrived in the last few decades like Crassula multicava and Chasmanthe aethiopica. The greatest change in species composition occurred between 1950 and 1960 (Figure 2). In the case of introduced species, the DCA revealed a major change between 1950 and 1960, but also (base in DCA axis II) a change between 1990 and 2000. As for early arrivals, we found Bidens pilosa or Solanum jasminoides, and for late arrivals we have species like Nicotiana glutinosa or Portulaca nicaraguensis (Figure 3). Finally, for native species (Figure 4), only the decade coordinates are indicated (more than 500 species cannot be plotted), revealing a substantial change in species composition in the 1970s and 80s, possibly due to the foundation of the Faculty of Biology of the University of La Laguna (although this information has been not analyzed it agree with an increased with the number of publications that appeared in that decade).

Figure 2 Species and decade scores in the space defined by axes I and II of DCA based on the presence of the invasive thermophile species following the Arechavaleta-Hernández et. al (2010) check list. Eigenvalues of axes I and II were 1.330 and 0.511, respectively, and the cumulative percentage of variance explained by both axes was 65.2 %. The names of the species use the first three letters of the genus and the first three letters of the specific epithet (Table 1 for species full names).

Figure 3 Species and decade scores in the space defined by axes I and II of DCA based on the presence of the introduced thermophile species following the Arechavaleta-Hernández et. al (2010) check list. Eigenvalues of axes I and II were 1.813 and 0.484, respectively, and the cumulative percentage of variance explained by both axes was 70.8 %. The names of the species use the first three letters of the genus and the first three letters of the specific epithet (Table 2 for species full names).

Figure 4 Decade scores in the space defined by axes I and II of DCA based on the presence of the native species following the Arechavaleta-Hernández et. al (2010) check list. Eigenvalues of axes I and II were 0.672 and 0.195, respectively, and the cumulative percentage of variance explained by both axes was 69.8 %.

When we correlated the decade coordinates of DCA- Axis I with the socioeconomic and temperature variables, the analysis revealed that native species are closely related to socioeconomic parameters over these decades. Additionally, with lower correlation strength, introduced species are also correlated with these variables and with mTEM; while invasive species revealed no correlation with any of the parameters used in the analysis. The DCA-Axis II did not reveal any correlation among these variables with the decade coordinates (Table 4).

Table 4 Pearson correlation coefficients for decades coordinates on axes I and II of DCA and socioeconomic and temperature anomaly variables.

| DCA - Axis I | DCA - Axis II | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Invasive | Introduce | Native | Invasive | Introduce | Native | |

| GDB | 0.843 | 0.943** | 0.970** | -0.793 | -0.691 | 0.521 | |

| POP | 0.887 | 0.948** | 0.968** | -0.725 | -0.604 | 0.529 | |

| TUR | 0.839 | 0.942* | 0.967** | -0.929 | -0.856 | 0.267 | |

| TEM | 0.809 | 0,819 | 0.779 | -0.533 | -0.413 | 0.589 | |

| mTEM | 0.911 | 0.936** | 0.918 | -0.720 | -0.598 | 0.478 | |

After multiple test Holm´s procedure (*) p <0.01; (**) p < 0.05; n = 7.

The direct gradient analysis (CCA) also showed similar patterns to the DCA. In the case of invasive species, the Montecarlo Test for the decade scores of CCA-Axis I with respect to the 4 explanatory variables (499 iterations) indicated that the only variable explaining species composition all along the axis is TOU (F = 6.25; p < 0.001), with the same result for the introduced ones (F = 9.110; p < 0.01), while for native, GDP was the only variable (F = 9.01, p < 0.01).

The correlation of species richness with the variables revealed a similar pattern for native and introduced species, where GDP, POP and TOU were significantly correlated with the increase in species richness, while for invasive, the correlated variable explaining the variability of species richness of this group was mTEM (Table 5).

Table 5 Pearson correlation coefficients for species richness over the decades and socioeconomic and temperature anomalies variables.

| Variables | Invasive | Introduce | Native |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDB | 0.913 | 0.979* | 0.946** |

| POP | 0.931 | 0.942** | 0.966* |

| TOU | 0.906 | 0.970* | 0.945** |

| TEM | 0.832 | 0.802 | 0.782 |

| mTEM | 0.938** | 0.913 | 0.918 |

After multiple test Holm´s procedure (*) p < 0.01; (**) p < 0.05; n = 7.

Discussion

Species invasions are governed by factors such as environmental conditions and species traits as well as human activities (Pyšek et al. 2010). It is well known that socioeconomic variables are driving forces of invasion across national and international boundaries (population, international trade, globalization economy, transport…); while aspects related to global warming and climate change appear to have less effect in some studies (Le Maitre et al. 2004) and as our results in this study demonstrate. The degree of development is directly related to the number of invasive species and the impact can be immediately evident or lag for a period over 100 years (Weber & Li 2008).

In our study, we have found a faster rate of increase in the number of invasive and introduced species than in the number of native species during these decades (Figure 1). Based on absolute numbers, introduced species is the group that has been increasing the fastest over the last seven decades. It is also true that we have centered the study on thermophile invasive and introduced species, as they have been considered more adaptable and responsive to global warming (Sobrino et al. 2001). Global warming is considered to affect ecophysiological processes of plant systems resulting in advances of thermophilic species and expansion of their ranges (Hilbert et al. 2001, Sobrino et al. 2001). Increases in CO2 and in temperature are determining factors related to the prevalence of invaders (Dukes & Mooney 1999).

In spite of the importance of global warming in favoring species to reach, up till now otherwise inhabitable areas (i.e. high altitudinal zones; Pauchard et al. 2009), we have found that socioeconomic aspects of development (GDP, POP and TOU) are important elements that better explain the increase in richness and changes in species composition. However, mTEM appears in these correlations as significant in the case of invasive species richness and in the case of DCA introduce species composition. The results are in some way similar to other studies, where economic variables similar to GDP (i.e. per capita real state) have been found as the most important variables to explain the distribution of non-native species (Taylor & Irwin 2004), as well as other indicators, such as the human development index (Weber & Li 2008) or population movements (Margolis et al. 2005). Population and tourism, in our case, have been revealed as the most consistent variables to explain species composition and species richness. In fact, these are the only variables that explain changes in invasive species composition and richness (Table 4) and are significant in other analyses, as demonstrated in other studies (Pyšek et al. 2010, Lockwood et al. 2005).

In our study, the increase in mTEM has only been significant in the case of invasive richness and introduced species composition. In other studies related to altitudinal gradients, minimum temperatures appear as a good predictor to displace the tree or other species line at higher altitudes (Dukes et al. 2009), including invasive ones, which have been revealed as another threat to well-protected altitudinal areas (Sheppard et al. 2014; Pauchard et al. 2009).

The number of tourist has not often been considered in studies about determinants that drive introduced species. In our case, it is very closely related to the number of introduced species, although it was also significant for the other groups of species richness as well as for explaining species composition. Tourism is the principal economic activity of the archipelago, with over 12 million visitors in 2012 (with an average stay of 10 days). We should consider the impact of tourism not just as a number, but also in terms of the numerous activities associated with tourism (excursions, spectacles, transport).

We expected that temperature anomalies (minimum) would play a more significant role in the changes in species composition and richness over the decades. In fact, we selected the thermophile species, expecting to favor the appearance of significant relationships. However, these relationships have been found to be very low, even when analyzing the data individually with species richness. In spite of these results, we still consider that temperature anomalies, as long as they follow IPCC predictions, will become an important driver of species invasion. Climatic changes predicted by the IPCC in the Mediterranean area are likely to determine significant changes in species forest composition. In fact, the moderate scenarios of the IPCC predict a severe decrease in precipitations and a rise of 3–4 °C in average temperatures (de Castro et al. 2004), with a similar scenario for Canary Islands based on the newest and most sensitive IPCC estimations (IPCC 2013). So far, changes detected over the past 70 years have not reached 2 °C. This could be the reason why this effect is not detectable yet, and also because of the great socioeconomic changes that affected the Canary Islands during these decades (tourism boom in the 60s, the arrival of democracy in 1974, joining the European Community 1984, etc.).

One of the results common to both native and introduced species is that they are affected by the same socioeconomic factors (although invasives were only significantly related to population), following the pattern that is known as “what it is good for native is also good for introduced species” (Stohlgren et al. 1999, Foster et al. 2002). In this case, despite the appearance of new of native or introduced species, we cannot relate this appearance to a “biological invasion crisis” but to a deeper economic development of the Canary Islands’ society that invests more in research and discovery of species. In fact, in the last five decades in Canary Islands has been described an average of three new species of terrestrial flora each year (Martín et al. 2005). It is also true that this economic development favors propagule dispersion at a faster rate than the appearance of native species, as found in our data, and this should be an important concern for environmental managers (Figure 1). As globalization is a force that favors propagule pressure (Lockwood et al. 2005), its association with the increase in the number of introduced species comes as no surprise. Something similar happens with the observed relationship between the invaders and mTEM; the less important the temperature is as a limiting factor, the greater the chances of survival, allowing better growth of alien species in the range introduced. This has been identified as one of the expected effects of climate change on biodiversity (Walther et al. 2009).

Climate change, including increased temperatures, decreased rainfall, and variation in daily/seasonal temperature ranges may facilitate the geographical extension of many invasive species, threatening native biodiversity (Caujape-Castells et al. 2010). Continuous monitoring and control of areas where non-native species are concentrated, including botanical gardens, personal gardens, landscaped public and government buildings, and commercial garden centers, among others, is recommended to prevent accidental escape and expansion of thermophile species favored by climate change in the near future, as has been recently suggested by McDougall et al. (2011). For Tenerife Island, golf courses are one of the main entrance of non-native species (Siverio 2012), becoming one of the main areas to control (not just the target species used for the field, also the involuntary introduce in the seeds and soil. The number of exotic species blacklisted should be expanded to include species that have an increased likelihood of becoming feral due to local warming. As it is revealed in this study, together with economic growth, the entrance of introduce species are expected to increase.

We cannot forget the importance of laws and regulation in order to control the movement an entrance of invasive and introduce species. A new Royal Decree Law (Real Decreto Ley 630/2013, 2013) has been enacted and approves to regulate the invasive and introduce species and stablishing strong limitations to the use.

Since 2007, the economic crisis has changed many socioeconomic variables in this study (study finished in 2010). Thus, in future studies, we will have a good opportunity to reveal the importance of the temperature anomalies (minimum and average) in species richness and composition. Clearly, multidisciplinary efforts will be necessary between ecologists and economists to reveal the external cost of the increasing presence of non-native species caused by economic growth. This will be valuable information before declaring and then facing battle against any future “biological invasion crises”.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)