Introduction

Ochroma pyramidale (Cav. ex Lam.) Urb. is a fast-growing pioneer tree native to America (Sandi & Flores, 2010). The species is distributed from southeastern Mexico, Central America, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia and the Antilles to Brazil (Sandi & Flores, 2010). Based on its distribution, the tree has acquired several common names, with balsa, balso, corcho and pochote standing out (Pennington & Sarukhán, 2005; Sandi & Flores, 2010). Ochroma pyramidale has ecological importance because it is used for the rehabilitation of degraded areas, while its commercial importance is due to the high strength and low density of the wood, which makes it one of the lightest and most useful for making aircraft parts, toys and handicrafts (González-Osorio, Cervantes, Torres, Sánchez, & Simba, 2010; Sandi & Flores, 2010).

The seeds of the species O. pyramidale are orthodox; that is, they are tolerant to dehydration (Ríos-García, Orantes-García, Moreno-Moreno, & Farrera-Sarmiento, 2018; Romero-Saritama, 2016). In addition, they present physical dormancy, so that even when favorable conditions are present, they are unable to germinate (Fang, Enhe, Qinli, & Zhuhong, 2016; Jiménez et al., 2017). This is an adaptive property present in some seeds that allows them to survive in unfavorable conditions (Doria, 2010). Dormancy is common in other tropical species, which causes variation in the percentage and speed of germination in their natural environment and in nursery conditions, generating strong heterogeneity in the growth of individuals (Galán-Larrea, Vargas-Hernández, & Rodríguez-Laguna, 2000). As for the genus Ochroma, studies have been carried out on the characteristics of its seeds and their germination, highlighting issues of viability (Ríos-García, Orantes-García, Moreno-Moreno, & Farrera-Sarmiento, 2016), morphophysiological characterization (Romero-Saritama, 2016; Vázquez-Yañes, 1976) and pre-germination treatments (Herrera & Alizaga, 1999; Jiménez et al., 2017; Vázquez-Yañes, 1974, 1975).

In the community of Lacanha Chansayab, located in the Lacandon Jungle, Lacandon peasants or small-scale farmers recognize two variants of the genus Ochroma, chac chujum (Ochroma pyramidale in its typical variety) and sac chujum (Ochroma pyramidale var. bicolor [Rowlee] Brizicky). These variants are distinguished in the field by the colour of their petioles and the size of their fruit. Morphological differences include the size, colour and shape of structures such as the stem, crown, flower, fruit, petioles, and upper face and underside of the leaf and seeds. However, at present, it is known that the genus Ochroma is monophyletic, so the morphological differences that the species presented led taxonomists and botanists to propose different species and varieties for the genus. Both varieties are used by traditional Mayan Lacandons for the early recovery of their acahuales.

This study aimed to determine the effect of seven pre-germination treatments applied on seeds of O. pyramidale in its typical variety and O. pyramidale var. bicolor in the Lacandon Jungle. The species presents dormancy and it is known that, in the Lacandon Jungle, the seeds of the O. pyramidale varieties begin to germinate after slash-and-burn; therefore, it is expected that the application of treatments will increase the germination percentage of the seeds, mainly in those where temperatures of 100 °C are applied.

Materials and methods

Study area

The Lacandon Jungle covers approximately one million hectares, including 53 % of the Usumacinta River basin (Secretaría de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca [SEMARNAP], 2000); it is located in the extreme east of the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico (16° 05’ - 17° 15’ N; 90° 25’ - 91° 45’ W) (Mendoza & Dirzo, 1999). The dominant vegetation is high evergreen forest (Pennington & Sarukhán, 2005). The collection site is located in the Lacanha Chansayab locality, within the area comprising the Lacandon Jungle, at geographic coordinates 16º 45’ 59’’ N and 91º 07’ 59’’ W. The germination treatments were evaluated in the Germplasm Laboratory of the "Dr. Faustino Miranda" Botanical Garden, operated by the Secretariat of the Environment and Natural History (SEMAHN) and located in Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas.

Seed collection

The fruits of chac chujum (Ochroma pyramidale) and sac chujum (O. pyramidale var. bicolor) were collected in Lacanha Chansayab (16° 45’ 59’’ N and 91° 07’ 59’’ W) in April 2014. Ten trees of each variety were selected, obtaining 10 fruits from each individual. The trees selected for harvesting the fruits had the following characteristics: diameter at chest height (DBH) greater than 60 cm, upper height of 18 m, abundance of ripe fruit and good phytosanitary status. The fruits were placed in the sun for drying, in order to encourage dehiscence. Subsequently, the seeds were obtained and mixed to homogenize the sample. The seeds were stored and kept in an airtight container in dark conditions, temperature of 4 to 5 °C and humidity of 4.5 to 8 %, to protect them from humidity, direct sunlight, insects and fungal or bacterial diseases.

Germination

Germination treatments were evaluated in February 2015 when the seeds had been stored for 10 months. Seeds from a previous year were used because balsa trees fructify from March to June. Table 1 shows the seven treatments chosen for their low cost. The treatments, with the exception of the control, were divided into three groups in order to break the dormancy of the seed through the permeability of the seed coat: 1) imbibition of the seed by water immersion; 2) thermal impact by boiling water at 100 °C and 3) thermal impact (100 °C) plus immersion in coconut water in a state of tender maturity. This water has been used in other species (Patiño, Mosuera, & Tulio, 2011; Quinto, Martínez-Hernández, Pimentel-Bribiesca, & Rodríguez-Trejo, 2009) because it contains nutrients and cytokinins that favor seed germination.

The experimental units were 90 x 15 mm Petri dishes, where 25 seeds were planted on filter paper and cotton. The dishes were introduced into a precision germinator (Seedburo, Equipment Company), programmed to illuminate 24 hours with 90 % relative humidity and a constant temperature of 27 °C. The number of germinated seeds was counted three times per week in a 56-day period. Due to the experiment’s logistical limitations, the number of seeds evaluated for germination was not adjusted in accordance with the rules of the International Seed Testing Association (ISTA). Rojas-Rodríguez and Torres-Córdoba (2009) report that some Ochroma seeds continue to germinate until 54 days; for this reason, germination was evaluated until that time. The emergence of the radicle defined the germinated seeds (Vázquez, Orozco, Rojas, Sánchez, & Cervantes, 1997). The Petri dishes were watered every other day and two applications of Captan (N-[trichloromethylthio]cyclohex-4-ene-1,2-dicarboximide) diluted at 5 % (fungicide) were made for fungal control; the first one was on March 9 and the second on April 8, 2015.

Table 1 Pre-germination treatments used for the experimental management of seeds of two varieties of balsa (Ochroma pyramidale).

| Treatment | Description | Replicates | Seeds per replicate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Control | 4 | 25 |

| Soaking12h | Soaking in water (12 h) at room temperature | 4 | 25 |

| Soaking24h | Soaking in water (24 h) at room temperature | 4 | 25 |

| Boiling3s | Boiling at 100 °C for 3 s | 4 | 25 |

| Boiling10s | Boiling at 100 °C for 10 s | 4 | 25 |

| Boiling3s + Soaking24h | Boiling (3 s) and soaking in coconut water (24 h) | 4 | 25 |

| Boiling10s + Soiling24h | Boiling (10 s) and soaking in coconut water (24 h) | 4 | 25 |

Statistical analysis

A randomized block experimental design was used with four replicates. The data were normalized using Arc sen (Rodríguez-Sosa, Valdés-Roblejo, & Rodríguez-Lías, 2012) in order to meet the assumptions of homogeneity of variance (Levene’s test). Subsequently, the data were interpreted using an analysis of variance (P = 0.05), which allows more than two means to be contrasted. In addition, a Tukey multiple comparison test (P = 0.05) was performed to know the difference between the groups. The analysis was performed with the SPSS statistical program version 15.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, 2009).

Results and discussion

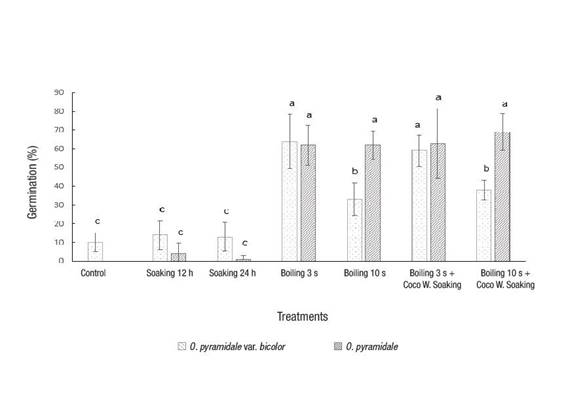

For the two varieties of the genus Ochroma, the effect of the treatments on seed germination was statistically different (Table 2). The treatments that favored germination were those that included immersing the seeds in boiling water. In the case of the O. pyramidale typical variety, the four treatments that included thermal impact generated the greatest germination and were statistically similar (P = 0.05), while for O. pyramidale var. bicolor, the Boiling3s and Boiling3s + Soaking24h treatments were the best (Figure 1). The percentages are similar to those reported by Herrera and Alizaga (1999), who obtained 68 % germination with water at 80 °C for 3 min. Vázquez-Yañes (1976) mentions that germination of the genus Ochroma is favored by high temperatures because the seeds have adapted to the occurrence of fire in the areas where they grow.

Table 2 Representation of analysis of varance statistical test of pre-germination treatments evaluated in Ochroma pyramidale seeds.

| Germination percentage | Sum of squares | Degrees of freedom | Root mean square | F | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inter-groups | 38 878.857 | 13 | 2 990.681 | 35.443 | .000 |

| Intra-groups | 3 544.000 | 42 | 84.381 | ||

| Total | 42 422.857 | 55 |

The lowest germination percentage was recorded in the control, Soaking12h and Soaking24h, treatments, being statistically similar (Figure 1). The low germination percentages in the control treatment agree with those obtained by Herrera-Quirós and Alizaga-López (1999) and Jiménez et al. (2017). This contrasts with the study by Ríos-García et al. (2016), who evaluated the viability of seeds at 0, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months of storage, without application of treatments, and obtained approximately 97.3 % germination at 0 months and 66 % at 12 months. However, although Ríos-García et al. (2016) did not use pre-germination treatments, they did use coconut powder and agrolite (1:2) in the substrate. Ayala-Sierra and Váldez-Aguilar (2008) also evaluated the effectiveness of coconut coir dust substrate combined with perlite and vermiculite (70:20:10) in six commercial species and concluded that germination was favorable compared to substrates combined with peat moss. Coconut coir dust is likely to have increased the germination percentage in O. pyramidale seeds, as observed in the coconut water treatments evaluated by Patiño et al. (2011) and Quinto et al. (2009).

In both varieties, the Soaking12h and Soaking24h treatments generated low germination percentages (Figure 1). These results are similar to those obtained by Rodríguez-Sosa et al. (2012), who evaluated nine pre-germination water immersion treatments at different intervals (3 to 27 h) in Colubrina ferruginosa Brong seeds. These researchers obtained that, after 12 h, the treatments presented a similar germination percentage as the control (39.7 %), decreasing as the immersion was prolonged (15 h = 38.5 % and 27 h = 22 %).

Figure 1 Germination of two varieties of Ochroma pyramidale under seven treatments. The standard deviation of the mean is represented above the bars. Treatments by variety that do not share the same letter are statistically different according to Tukey's test. (P = 0.05).

The boiling treatments had similar germination percentages (Figure 1) with the exception of the Boiling10s and Boiling10s + Soaking24h treatments for O. pyramidale var. bicolor. At a physiological level, it is possible that the seed coat will have greater permeability as a result of high temperatures (immersion in boiling water), thereby favoring germination. The exposure time of the seeds to the high temperatures (100 °C) and growth phytohormones (cytokinins) present in the coconut water favorably influenced germination capacity. According to the results, the seeds must be subjected to high temperatures to increase the germination percentages, as indicated by Herrera and Alizaga (1999), Jiménez et al. (2017) and Vázquez-Yañes (1974, 1975). With respect to coconut water, the soaking of the seeds should be done after immersion in boiling water; in case of only applying the soaking, the seeds will not absorb the cytokinins effectively, due to the impermeability of the Ochroma seed coat. This is corroborated in the study by Jiménez et al. (2017), who obtained a low germination percentage (20.51 %) when they soaked the seeds in coconut water for 12 hours. By contrast, Quinto et al. (2009) evaluated three coconut water-based pre-germination treatments in non-dormant seeds using three stages of fruit maturity (young, mature and dry). The treatments favored the germination of Swietenia macrophyla King, Cedrela odorata L. and Tabebuia rosea (Bentol) DC, obtaining a higher percentage with coconut water from young fruit (40.3, 30.7 and 31.7 %, respectively), despite the fact that the seeds had a viability of 94, 96 and 99 %, respectively. According to Quinto et al. (2009), the amount of nutrients and the specific composition of the coconut will depend on the maturity of the fruit; the lower the maturity, the higher the concentration of nutrients, as well as phytohormones, including cytokinins.

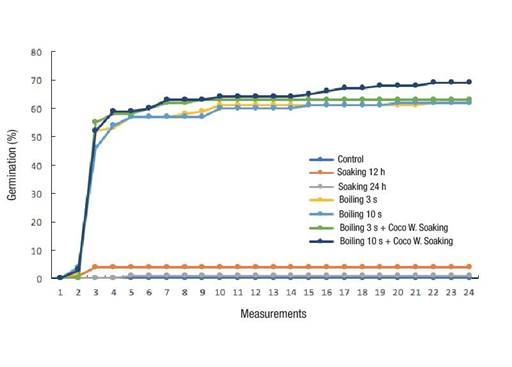

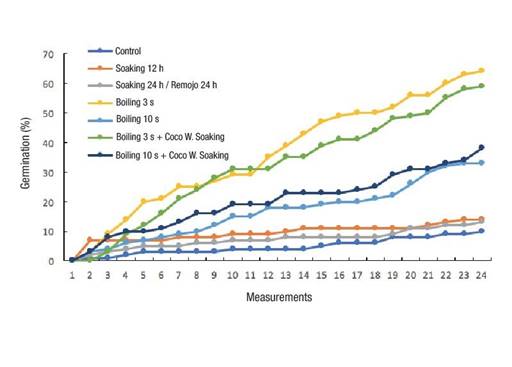

Figures 2 and 3 show the germinative performance of each of the varieties over 56 days; in O. pyramidale, germination is logarithmic, and in O. pyramidale var. bicolor it is exponential.

Figure 2 Germination of Ochroma pyramidale typical variety under seven pre-germination treatments. Twenty-four measurements were made during the 56 days of evaluation.

Figure 3 Germination of Ochroma pyramidale var. bicolor under seven pre-germination treatments. Twenty-four measurements were made during the 56 days of evaluation.

In the Ochroma pyramidale typical variety, the boiling treatments produced the highest germination values (Figures 1 and 2), being statistically similar (P > 0.05). However, there was an increase in the germination percentage (7 %) of the Boiling10s + Soaking24h treatment (69 %) with respect to the treatment of the same temperature exposure time but which did not have soaking in coconut water (Boiling10s = 62 %). Regarding Ochroma pyramidale var. bicolor, apparently, the seeds can germinate without application of germination treatments (Figures 1 and 3); however, the highest germination values were obtained by Boiling3s (64 ± 14.6 %; F 1,13 = 35.44, P < 0.001). It is important to mention that O. pyramidale var. bicolor seeds were susceptible to the boiling (100 °C) water immersion time since there were differences in germination, being statistically higher (P = 0.05) at 3 s (Boiling3s = 64 % and Boiling3s + Soaking24h = 59 %) than at 10 s (Boiling10s = 33 % and Boiling10s + Soaking24h = 38 %). In addition, as in the typical variety, germination increased 5 % with the Boiling10s + Soaking24h treatment, compared to the treatment with the same temperature exposure time but not soaked in coconut water (Boiling10s).

Conclusions

This study allows knowing the best management of Ochroma pyramidale seeds at low cost. Although the genus has only one species and all those previously identified above are synonymous, the germination percentages of the two varieties evaluated were different. These differences are associated with the type of treatment and germinative performance over time (logarithmic and exponential). The highest germination percentage, for both varieties, was obtained with water immersion treatments (100 °C) under different exposure times; O. pyramidale var. bicolor had higher germination with 3 s immersion. Coconut water did not produce the expected germination (higher percentage in both varieties and statistical differentiation with respect to treatments without coconut water); for this reason, it is suggested that synthetic cytokinins be used in future experiments to control the phytohormone dose and thus verify its effect on germination.

texto en

texto en