Introduction

Mesquite (Prosopis spp.) is an important forest resource for residents in northern Mexico’s arid and semi-arid regions. In these areas, mesquite is used to obtain firewood, wood, charcoal and pods that, because of their high fiber content, are destined for the feeding of domestic animals and wildlife (López et al., 2010; Ríos, Martínez, & Mojica, 2013; Rodríguez et al., 2014). Due to its low moisture content and great stability, the wood is used in construction, furniture making and handicrafts (Ríos et al., 2013).

The genus Prosopis has great economic and ecological potential; it grows naturally in northern Mexico’s arid and semi-arid areas, where precipitation is less than 400 mm per year (Ríos et al., 2013). In 2002, native stands of this genus occupied 262 193 ha, distributed in the states of Chihuahua (124 670 ha), Coahuila (73 868 ha), Durango (44 211 ha) and Zacatecas (19 444 ha) (Trucios, Ríos, Estrada, Valenzuela, & Jacinto, 2011). In recent years, nursery mesquite production for the restoration of altered ecosystems has increased considerably (Prieto, Rosales, Madrid, Mejía, & Sigala, 2013). However, there is little experience in terms of cultivation; some factors such as small plants, damage by hares, shallow soil, drought and a lack of practices that promote water harvesting have influenced the low survival of the plantations (Ríos-Saucedo, Rivera-González, Valenzuela-Núñez, Trucíos-Caciano, & Rosales-Serna, 2012).

For the above reasons, it is necessary to search for alternatives that enable the plants to acquire the appropriate morphological characteristics in the nursery for their proper rooting in the planting sites (Prieto et al., 2013). The use of complementary inputs to plant production, such as water-holding polymers, is an alternative to make their water uptake more efficient (Palacios-Romero et al., 2017). These have been used for more than 40 years in other productive areas such as agriculture (Landis & Haase, 2012), floriculture and fruit growing, but in Mexico there has been little exploration in the forestry field (Sandoval-Méndez, Cetina-Alcalá, Yeaton, & Mohedano-Caballero, 2000) and even less in the genus Prosopis.

Hydrogel or "solid rain" is a hydrophilic polymer, capable of absorbing water more than 100 times its weight (López-Elías, Garza, Jiménez, Huez, & Garrido, 2016); in addition, it can reduce evapotranspiration and mitigate drought stress (Cheruiyot et al., 2014). Another complementary option in the nursery is the evaluation of alternative substrates to the base mixture (55 % peat moss + 24 % vermiculite + 21 % agrolite), such as composted bark mixed with peat moss (Prieto et al., 2013). It is also necessary to test irrigation frequencies to determine how they influence the moisture retention of substrates with different characteristics. In this context, the objective of the present study was to evaluate the effect of five moisture retainer doses, two substrate mixtures and two irrigation frequencies on the morphological growth of Prosopis laevigata (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd.) M. C. Johnst. in the nursery.

Materials and methods

Study area location

The work was carried out in the forest nursery of the Valle del Guadiana Experimental Field of the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP for its initials in Spanish), located at km 4.5 of the Durango-Mezquital highway in Durango, Mexico, at coordinates 23° 59′ 23.6″ NL and 104° 37′ 30.1″ WL, at an elevation of 1 860 m.

The plant was produced in a greenhouse covered with 720-gauge, UV-blocking plastic and with a 50 % shade mesh. The average light intensity was 168 klx. The temperature ranged from 10.5 to 40.2 °C, while the relative humidity fluctuated between 17.1 and 94.3 %. The seed was harvested in San Isidro, municipality of Nombre de Dios, Durango, located at coordinates 23° 57′ 14.32″ NL and 104° 17′ 07.25″ WL.

Experimental design

Twenty treatments derived from the combination of the following factors were evaluated: a) two substrates: base mixture (peat moss [55 %] + vermiculite [24 %] + agrolite [21 %]) and composted bark (50 %) + peat moss (50 %); b) two irrigation frequencies (48 and 96 h) applied during the last 61 days of the 91-day trial; and c) five moisture retainer doses (0.0, 1.5, 3.0, 4.5 and 6.0 g·L-1). The treatments were distributed under a randomized block experimental design with a 5 x 2 x 2 factorial arrangement. Each experimental unit consisted of a tray with 77 plants. Four replicates were evaluated per treatment.

Plant production process

As a pregerminative treatment, the seed was soaked in water at 90 °C for 75 s and disinfected in a solution composed of 90 % water and 10 % commercial chlorine for 10 min; subsequently, to avoid damage due to damping off during germination, it was impregnated with the fungicide Daconil®. Two mixtures were used as substrate, to which the controlled release fertilizer Osmocote® (17-7-12 N-P-K) was added at a dose of 5 kg·m-3 of mixture. During the preparation of the substrates the polymer was added according to the treatments defined in Table 1. The seeds were deposited in polystyrene trays with 77 cavities with a capacity of 170 mL per cavity.

Table 1 Treatments to evaluate the morphological growth of Prosopis laevigata under five moisture retainer doses, two substrate mixtures and two irrigation frequencies.

| Treatment | Substrate | Moisture retainer (g·L-1 substrate) | Irrigation frequency (h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Base mixture | 0.0 | 48 |

| 2 | Base mixture | 1.5 | 48 |

| 3 | Base mixture | 3.0 | 48 |

| 4 | Base mixture | 4.5 | 48 |

| 5 | Base mixture | 6.0 | 48 |

| 6 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 0.0 | 48 |

| 7 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 1.5 | 48 |

| 8 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 3.0 | 48 |

| 9 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 4.5 | 48 |

| 10 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 6.0 | 48 |

| 11 | Base mixture | 0.0 | 96 |

| 12 | Base mixture | 1.5 | 96 |

| 13 | Base mixture | 3.0 | 96 |

| 14 | Base mixture | 4.5 | 96 |

| 15 | Base mixture | 6.0 | 96 |

| 16 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 0.0 | 96 |

| 17 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 1.5 | 96 |

| 18 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 3.0 | 96 |

| 19 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 4.5 | 96 |

| 20 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 6.0 | 96 |

Base mixture = peat moss (55 %) + vermiculite (24 %) + agrolite (21 %); CB = composted bark; PM = peat moss.

One month after plant emergence, nutrition was supplemented with the water-soluble fertilizer Master Growing Forestal® (20-7-19 N-P-K) at a dose of 0.5 g·L-1 of water at the development stage. In the preconditioning phase, Master Growing Forestal® (4-25-35 of N-P-K) was applied at a dose of 1.5 g·L-1. Each type of fertilizer was applied over a 30-day period with a frequency of 96 h.

Variables evaluated

The porosity and moisture behavior, due to the substrates and moisture retainer doses, were determined in four samples per substrate type with the methodology proposed by Landis, Tinus, McDonald, and Barnett (1990), based on the following formulas:

The moisture content was determined for each substrate mixture and moisture retainer dose. For this, initially the dry weight of the substrate was obtained in the containers and then the weight of the substrate with moisture at two times: immediately after irrigation and 48 h later. This process was repeated four times.

At three months of age, five plants per experimental unit were randomly extracted. In total, 400 plants (20 treatments*four blocks*five plants per treatment) were evaluated, from which the substrate was removed and the following variables recorded: height determined with a 30-cm graduated ruler, neck diameter measured with a digital Vernier caliper with 0.001 mm precision and shoot, root and total dry biomass (g), obtained by drying the components in a stove at 72 °C until constant weight.

Data were subjected to an analysis of variance by means of SAS software version 9.2 (Statistical Analysis System [SAS Institute], 2002), using the PROC GLM procedure. When significant differences were found among treatments (P < 0.05), means comparison tests were performed using Tukey's range test.

Results and discussion

Effect of substrate on growth of P. laevigata

The substrate factor caused statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) in plant growth in the variables height, diameter and shoot and total biomass (Table 2), which were 23.9, 19.4, 31.5 and 27.7 % higher, respectively, with the base mixture compared to the substrate composed of 50 % CB + 50 % PM.

Table 2 Growth variables of Prosopis laevigata, at three months of age, under different substrate, irrigation and moisture retainer conditions.

| Factor/Treatment | Height (cm) | Diameter (mm) | Root dry biomass (g) | Shoot dry biomass (g) | Total dry biomass (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | |||||

| Base mixture | 25.29 ± 1.84 a | 1.91 ± 0.09 a | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | 0.54 ± 0.06 a | 0.65 ± 0.06 a |

| 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 19.24 ± 1.30 b | 1.54 ± 0.08 b | 0.10 ± 0.012 a | 0.37 ± 0.04 b | 0.47 ± 0.05 b |

| Irrigation frequency | |||||

| Every 48 h | 23.86 ± 0.60 a | 1.73 ± 0.03 a | 0.11 ± 0.00 a | 0.48 ± 0.05 a | 0.59 ± 0.02 a |

| Every 96 h | 20.68 ± 0.52 b | 1.73 ± 0.03 a | 0.10 ± 0.00 a | 0.43 ± 0.05 b | 0.53 ± 0.02 b |

| Moisture retainer | |||||

| 0 g·L-1 | 19.27 ± 1.45 b | 1.55 ± 0.08 c | 0.09 ± 0.01 b | 0.36 ± 0.04 b | 0.45 ± 0.04 b |

| 1.5 g·L-1 | 22.73 ± 0.73 a | 1.71 ± 0.08 abc | 0.11 ± 0.01 a | 0.49 ± 0.05 a | 0.60 ± 0.06 a |

| 3 g·L-1 | 22.47 ± 1.41 a | 1.82 ± 0.07 ab | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.46 ± 0.04 a | 0.56 ± 0.04 a |

| 4.5 g·L-1 | 23.44 ± 1.74 a | 1.86 ± 0.08 a | 0.11 ± 0.012 a | 0.50 ± 0.05 a | 0.61 ± 0.06 a |

| 6 g·L-1 | 23.44 ± 1.50 a | 1.68 ± 0.08 bc | 0.11 ± 0.012 a | 0.47 ± 0.05 a | 0.58 ± 0.06 a |

Base mixture = peat moss (55 %) + vermiculite (24 %) + agrolite (21 %); CB = composted bark; PM = peat moss. ± Standard error of the mean. Different letters for the same variable, by factor, indicate significant differences according to Tukey's range test (P < 0.05).

The base mixture led to better plant performance. This agrees with the results obtained by Prieto et al. (2013) in P. laevigata plants produced in five substrate mixtures based on composted bark (50 to 80 %) combined with base mixture (20 to 50 %), considering a control (base mixture similar to that of this trial).

Figure 1 shows the porosity of the substrates evaluated. Landis et al. (1990) recommend certain ranges of total porosity (60 to 80 %), water-holding capacity (25 to 55 %) and aeration porosity (25 to 35 %). In the present work, it was found that in both substrates only the aeration porosity is in the range proposed by these authors. This may be due to the size of the particles in the substrates, because if the particle size increases, the amount of water retained decreases and the total pore space increases (Cruz et al., 2013). Also, the composted bark has a relatively low moisture retention capacity, which can be corrected by mixing it with other materials such as peat moss (García, Alcantar, Cabrera, Gavi, & Volke, 2001).

Figure 1 Total porosity, aeration porosity and water-holding capacity in two substrate mixtures. Base mixture = peat moss (55 %) + vermiculite (24 %) + agrolite (21 %). Different letters for the same variable indicate significant differences according to Tukey's test (P < 0.05). The standard error of the mean is shown on the bars.

Hernández, Aldrete, Ordaz, López, and López (2014) produced Pinus montezumae Lamb. using different proportions of bark, sawdust, peat moss, perlite and vermiculite. In the treatments where they used composted bark in different proportions, aeration porosity ranged from 30 to 35 %, while the control (60 % peat moss + 30 % agrolite + 10 % vermiculite) obtained the lowest value (26 %), which is similar to the level obtained in this experiment, where the same elements of the control were used, only in a different proportion (55 % + 21 % + 24 %).

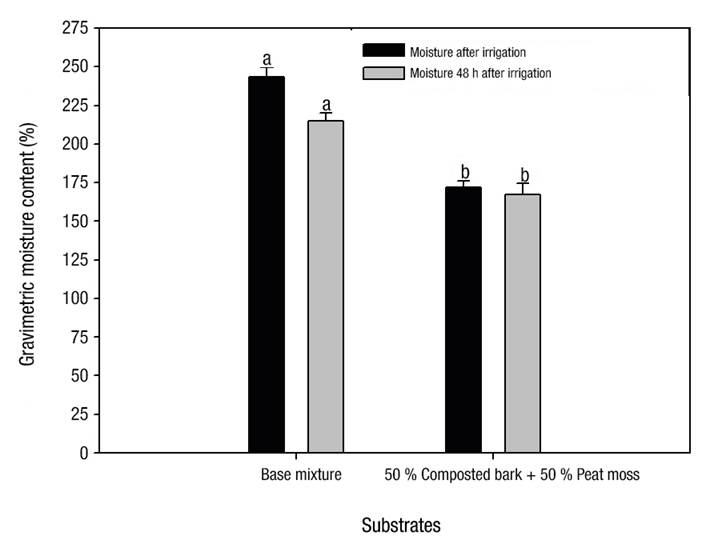

Regarding the moisture content in the substrates (Figure 2), there were also significant differences (P < 0.05) among treatments. In the case of the base mixture, the value after irrigation was 243.4 %, while for the composite mixture (50 % CB + 50 % PM) it was 171.7 %; by contrast, 48 h after watering the plant, the value decreased to 214.7 % for the base mixture and 167.1 % for the composite. Although the moisture content, at 48 h after irrigation, decreased more in the base mixture (28.7 % vs. 4.6 % for the composite mixture), this treatment maintained higher moisture, since the initial content was 29.4 % higher than in the composite mixture.

Figure 2 Gravimetric moisture content after irrigation and 48 h later in two substrate mixtures. Base mixture = peat moss (55 %) + vermiculite (24 %) + agrolite (21 %). Different letters for the same bar color indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05). The standard error of the mean is shown on the bars.

Effect of irrigation on growth of P. laevigata

When the plants were watered every 48 h, the variables height and shoot and total dry biomass production were 13.3, 10.4 and 10.2 % higher, respectively, than those irrigated every 96 h; the diameter and root biomass variables did not show statistical differences (P > 0.05, Table 2).

Maldonado, Aldrete, López, Vázquez, and Cetina (2011) reported that, in Pinus greggii Engelm., irrigation every 96 h led to height being up to 50 % lower in relation to the most frequent irrigations, which also occurred in the present study, only to a lesser degree (13.3 %). Ávila-Flores, Prieto-Ruíz, Hernández-Díaz, Wehenkel, and Corral-Rivas (2014) irrigated Pinus engelmannii Carr. with frequencies of 48, 96 and 192 h over 40 days and found that irrigation every 48 h favored plant growth in terms of height, diameter and biomass to a greater extent. In another study, López, Fernández, and Verga (2012) produced plants of Prosopis chilensis (Molina) Stuntz, Prosopis flexuosa DC. and two hybrids, to which irrigations were applied every 48, 72 and 120 h; the best growth in height and biomass was obtained with the most frequent irrigation condition. The results of the previous studies, although with different species, coincide with those of the present trial in the sense that frequent irrigation favors available moisture and, consequently, plant growth (Figure 2; Table 2).

On the other hand, López et al. (2014) demonstrated that the flood irrigation system promotes better root development and density in the production of P. laevigata in the nursery. In the present work there were no significant differences in root biomass production, while height and shoot biomass were higher with the most frequent irrigations.

Effect of moisture retainers on growth of P. laevigata

The moisture retainer doses showed significant differences (P < 0.05) in the variables evaluated (Table 2) with maximum differences among treatments of 17.8 % for height, 16.7 % for neck diameter, 18.2 % for root dry biomass, 28.0 % for shoot biomass and 26.2 % for total biomass. With the exception of the control (without moisture retainer), which was located at the lower statistical level in all evaluated variables, there was no defined behavioral trend in the other treatments, except for neck diameter where the plant cultivated with the 4.5 g·L-1 moisture retainer dose stood out.

With respect to moisture, the 6.0 and 4.5 g·L-1 doses resulted in the highest content in the substrate (P < 0.05) immediately after irrigation and 48 h later (Figure 3). However, the addition of a higher moisture retainer dose did not necessarily favor plant growth, so one can reduce the dose and get similar results.

Figure 3 Gravimetric moisture content in the substrate, after irrigation and 48 h later, with different moisture retainer doses. Different letters for the same bar color indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test (P < 0.05). The standard error of the mean is shown on the bars.

Lazarević, Vilotic, and Keca (2015) applied polymers in the production of Quercus ilex L. and Acer dasycarpum Ehrh. in the nursery, which led to greater growth. These results agree with those of Lahís, Luduvico, Glauce, and Marcos (2015), who added moisture retainers (0 to 4 g·L-1 of substrate) in Handroanthus ochraceus (Cham.) Mattos and found that doses of 2 to 4 g·L-1 generated the conditions for greater plant growth in height and diameter in the nursery. The above results coincide in the sense that applying moisture retainers favors plant growth, since moisture is available for a longer time in the substrate, facilitating absorption by the root system (Chirino, Vilagrosa, & Vallejo, 2011).

Landis and Haase (2012) indicate that when moisture retainers are applied, fine roots are protected against desiccation, improving root-to-soil contact. In studies carried out in Picea abies (L.) Karst, Pinus sylvestris L. and Fagus sylvatica L., hydrogel increased the root biomass from 5 to 45 times in comparison with the control (without hydrogel), which favored survival in sandy soils compared to other soils (Orikiriza et al., 2013). In the case of the present work, root biomass production showed percentage differences of up to 18.2 % in relation to the control; possibly, the plant took advantage of the available moisture for the root system to increase in volume.

Interaction of substrate, irrigation frequency and moisture retainer factors on growth of P. laevigata

The effect of substrate, moisture retainer and irrigation frequency interaction was significant (P < 0.05) in the evaluated variables. Table 3 shows the results of the interaction of these factors. The variables that showed the best response are generally associated with the use of the base mixture as substrate, irrigation every 48 h and 4.5 g·L-1 of moisture retainer. Although this dose slightly outperformed the others, its results are similar to those of 1.5 and 6.0 g·L-1; the lowest dose may be a viable option since it contains two-thirds less product than the 4.5 g·L-1 one, which in turn implies lower costs.

Table 3 Variables evaluated in Prosopis laevigata produced in the nursery by a combination of substrates, moisture retainers and irrigation frequencies.

| Substrates | Moisture retainer (g·L-1 substrate) | Irrigation frequency (h) | Height (cm) | Diameter (mm) | RDB (g) | SDB (g) | TDB (g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Base mixture | 0.0 | 48 | 21.38 ± 1.92 abcde | 1.74 ± 0.08 abcde | 0.09 ± 0.01 ab | 0.38 ± 0.04 abcdef | 0.47 ± 0.05 abcde |

| 2 | Base mixture | 0.0 | 96 | 21.68 ± 1.47 abcde | 1.87 ± 0.10 abcd | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.48 ± 0.05 abcdef | 0.60 ± 0.06 abcde |

| 3 | Base mixture | 1.5 | 48 | 28.94 ± 1.77 a | 1.99 ± 0.09 ab | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.59 ± 0.06 ab | 0.71 ± 0.07 ab |

| 4 | Base mixture | 1.5 | 96 | 24.27 ± 2.18 abcde | 1.89 ± 0.09 abc | 0.11 ± 0.01 ab | 0.53 ± 0.07 abcde | 0.65 ± 0.08 abcd |

| 5 | Base mixture | 3.0 | 48 | 26.75 ± 2.16 a | 1.85 ± 0.10 abcd | 0.09 ± 0.01 ab | 0.57 ± 0.06 abc | 0.66 ± 0.07 abcd |

| 6 | Base mixture | 3.0 | 96 | 24.17 ± 1.35 abcde | 1.98 ± 0.08 ab | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.53 ± 0.04 abcde | 0.65 ± 0.05 abcd |

| 7 | Base mixture | 4.5 | 48 | 28.33 ± 2.36 a | 2.05 ± 0.09 a | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.62 ± 0.07 a | 0.74 ± 0.09 a |

| 8 | Base mixture | 4.5 | 96 | 25.19 ± 1.88 abcd | 1.89 ± 0.08 abc | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.56 ± 0.05 abc | 0.68 ± 0.06 abc |

| 9 | Base mixture | 6.0 | 48 | 25.91 ± 1.87 abc | 1.87 ± 0.08 abc | 0.11 ± 0.01 ab | 0.55 ± 0.06 abcd | 0.65 ± 0.07 abcd |

| 10 | Base mixture | 6.0 | 96 | 26.30 ± 1.43 ab | 1.98 ± 0.07 ab | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.59 ± 0.05 ab | 0.70 ± 0.05 ab |

| 11 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 0.0 | 48 | 17.75 ± 1.18 cde | 1.16 ± 0.07 f | 0.09 ± 0.01 ab | 0.29 ± 0.03 ef | 0.38 ± 0.04 cde |

| 12 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 0.0 | 96 | 16.29 ± 1.24 e | 1.45 ± 0.06 def | 0.06 ± 0.01 b | 0.28 ± 0.03 f | 0.34 ± 0.04 e |

| 13 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 1.5 | 48 | 21.00 ± 1.71 abcde | 1.39 ± 0.09 ef | 0.14 ± 0.01 a | 0.51 ± 0.05 abcdef | 0.65 ± 0.07 abcd |

| 14 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 1.5 | 96 | 16.70 ± 1.26 e | 1.58 ± 0.06 bcdef | 0.09 ± 0.01 ab | 0.33 ± 0.04 cdef | 0.42 ± 0.05 bcde |

| 15 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 3.0 | 48 | 22.64 ± 1.48 abcde | 1.89 ± 0.06 abc | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.46 ± 0.03 abcdef | 0.58 ± 0.04 abcde |

| 16 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 3.0 | 96 | 16.31 ± 0.68 e | 1.57 ± 0.06 bcdef | 0.08 ± 0.01 ab | 0.30 ± 0.02 def | 0.38 ± 0.03 de |

| 17 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 4.5 | 48 | 21.74 ± 1.43 abcde | 1.91 ± 0.08 ab | 0.11 ± 0.02 ab | 0.45 ± 0.05 abcdef | 0.56 ± 0.06 abcde |

| 18 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 4.5 | 96 | 18.51 ± 1.28 bcde | 1.59 ± 0.09 bcde | 0.09 ± 0.01 ab | 0.37 ± 0.04 bcdef | 0.46 ± 0.05 abcde |

| 19 | 50 % CB+ 50 % PM | 6.0 | 48 | 24.14 ± 1.72 abcde | 1.47 ± 0.06 cdef | 0.12 ± 0.01 ab | 0.48 ± 0.05 abcdef | 0.60 ± 0.06 abcde |

| 20 | 50 % CB + 50 % PM | 6.0 | 96 | 17.40 ± 0.99 de | 1.41 ± 0.13 ef | 0.11 ± 0.02 ab | 0.34 ± 0.04 cdef | 0.44 ± 0.05 bcde |

Base mixture = peat moss (55 %) + vermiculite (24 %) + agrolite (21 %); CB = composted bark; PM = peat moss, RDB = root dry biomass, SDB = shoot dry biomass, TDB = total dry biomass. ± Standard error of the mean. Different letters for the same variable indicate significant differences according to Tukey's range test (P < 0.05).

The combination of the factors irrigation frequency and moisture retainer dose may be favorable under certain conditions, as in this study. This does not coincide with the results of Sandoval-Méndez et al. (2000) in Pinus cembroides Zucc., where the combination of abundant and limited irrigations with different hydrogel doses only favored growth in height in the abundant irrigation, regardless of the polymer dose used.

Pereira, Monteiro, and Madureira (2013) produced Passiflora edulis Sims plants by applying irrigation intervals of 24, 48 and 72 h with 0 and 3·g L-1 of hydrogel in the substrate composed of soil plus manure (3:1) and Bioplant®. These authors obtained the best results in biomass production with the 3 g·L-1 hydrogel treatment, regardless of the irrigation frequency. Again, the importance of adequate water use to promote plant growth, as was the case in the present study, is evident, although the substrate was the most influential factor.

Although the plant was under experimentation for only three months, the maximum differences in the response variables were considerable: height (16.3 to 28.9 cm), diameter (1.16 to 2.05 mm), root biomass (0.06 to 0.14 g), shoot biomass (0.28 to 0.62 g) and total biomass (0.34 to 0.74 g), showing that the influence of the evaluated factors (substrate, irrigation frequency and moisture retainer dose) was noteworthy with the most positive effects obtained with the base mixture, irrigation every 48 h and the application of moisture retainers at doses of 1.5, 4.5 or 6.0 g·L-1 of substrate.

Based on the results obtained, the substrate factor was the one that most influenced plant growth, since it generated the greatest differences in the response variables, among treatments, with ranges from 19.4 to 28.0 %; after that, the effect of the moisture retainers was demonstrated with maximum differences among treatments of 16.7 to 27.7 %, and finally, the irrigation frequency factor had maximum differences of 13.3 %.

Conclusions

Substrate was the factor that most influenced the quality of Prosopis laevigata plants, followed by irrigation frequency and moisture retainers. The combinations formed by the base mixture (peat moss [55 %] + vermiculite [24 %] + agrolite [21 %]), irrigation every 48 h and moisture retainer at doses of 1.5, 4.5 or 6.0 g·L-1 of substrate were the ones that most contributed to increased plant height, diameter and biomass production. The results found may serve as a basis for exploring other possibilities to improve the quality of the plant.

texto en

texto en