Introduction

In Mexico, production means and territory rights of rural and indigenous communities have been exploited. In these communities, the transformation of traditional management units (TMU) decreases the quality of life, infringes on the culture that has been passed on among generations and marginalizes the knowledge shared among communities (Gómez-Baggethun, Mingorría, Reyes-García, Calvet, & Montes, 2010). TMU are production systems that directly depend on natural resources; they are comprised of the collection of processes through which the available resources are exploited in the natural territorial units, such as the forests and the lowland deciduous forests (LDF) and in those transformed units such as agriculture, livestock, and fruit orchards.

The fragmented territory jeopardizes the natural resources shifting them from useful values to commercialization and prioritizing production over the welfare of the ecosystem (O'Sullivan, 2008). The causes of the aforementioned changes are: disorganized urban growth, infrastructure demand, monospecific agriculture, migration and cultural changes, expressions of the global economic crisis (Brown, 2003; Harvey et al., 2008; Toledo, Ortiz-Espejel, Cortés, Moguel, & Ordoñez, 2003). Faced with this problem, the State has not proposed any strategies that prevent the fragmentation and, therefore, the loss of local productive culture. On the contrary, there is less political willingness and technical capacity to overcome the actions that destroy the traditional organizations of the rural communities (Gómez-Baggethun et al., 2010). Among these, the productive culture prevails with the conservation of ethnobotanical variables that when systematized can be applied to the planning of soil use for sustainable development of the communities (Caro, Quinteros, & Mendoza, 2007).

The importance of the participatory diagnosis of the TMU, such as cornfields, traditional orchards (Gómez-Pompa, 1993), LDF (Monroy-Ortíz et al., 2009), and secondary and mature forests managed by the native groups (García-Frapolli, Toledo, & Martínez-Alier, 2008) has been documented. The TMUs show ethnobiological variables of community conservation; these are understood as the collection of appropriation forms and sustained productions of natural resources, derived from the holistic view of the territory of rural groups and from the primacy in the social destiny of production and of the market solely in a secondary manner (Colín & Monroy, 2004; Leff, 2011; Toledo & Barrera-Bassols, 2008).

Based on the aforementioned, it was planned to diagnose the TMU of the community of San José de los Laureles, located in the Protected Natural Area, Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin in Morelos, in order to present participatory community conservation strategies. The diagnosis is based on the assumption that the period of validity of these productive units is the result of their community conservation state, based on the knowledge, management and usage of the biological diversity. The knowledge variables were used in the management and usage of species abundance of the TMUs still under the ownership of the people of San José de los Laureles.

Materials and methods

Field of study

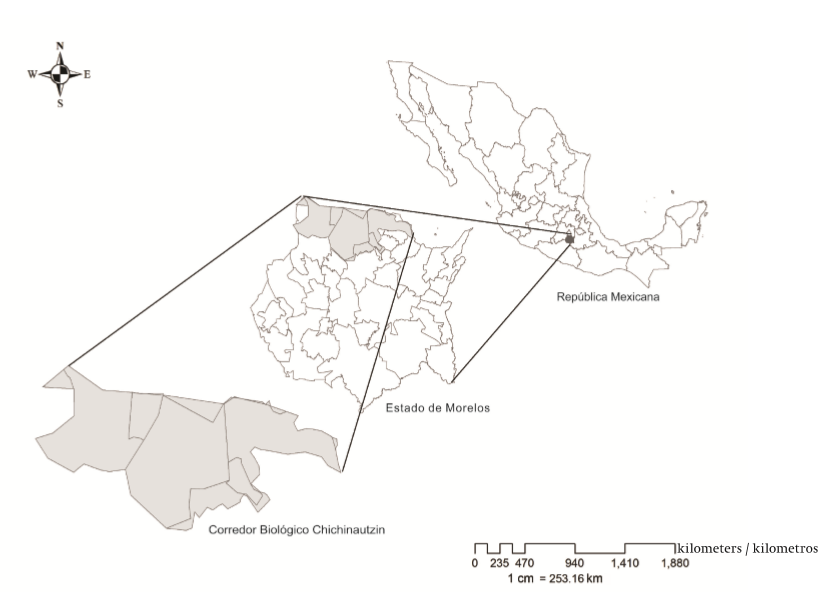

San José de los Laureles, municipality of Tlayacapán, is located in the Protected Natural Area, Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin, in northern Morelos, Mexico (Figure 1). The vegetation is comprised of pine forest, oak forest and relicts of lowland deciduous forest (LDF) (Miranda & Hernández, 1963). The weather is semi-warm, sub-humid, with rain during the summer; the temperature varies between 18 and 22 °C, similar to Ganges (Taboada, Reyna, & Oliver, 1992).

Figure 1. Location of the Protected Natural Area, Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin in Morelos, México.

The community is highly marginalized and of Nahuatl descent (Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas [CDI], 2010), formerly known as Tlalmimilolpan, or "land of the sacred leaves" referring to Laurel (Litsea glaucencens Kunth). In the era of Mexican domination, laurel leaves were used as tribute payment to the tlatoani (Plancarte & Navarrete, 1934); presently, the leaves are collected by people unconnected to the community to be sold in regional markets. The population is comprised of 1,377 individuals, among which 12 % speak nahuatl (Secretaría de Desarrollo Social [SEDESOL], 2013). Monospecific agricultural production is prioritized by Lycopersicon esculentum Mill. tomatoes and Opuntia sp. nopal, even though their commercialization is controlled by intermediaries (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía [INEGI], 2010).

Types of organization

The organization was described based on semi-structured interviews applied to 10 key informants, selected on their traditional knowledge and leadership (Galeano, 2007; García-Frapolli et al., 2008).

Participatory diagnosis

The participatory diagnosis of the TMUs was done through ethnobotanical variables identified in three workshops with 60 participants each. In the first workshop, the participants' perception in regards to the conflicts that arise from the changes in soil use was inquired. For this, and based on semi-structured interviews, the following was asked: ¿What do agriculture, forests, and livestock farming mean? And secondly, ¿what are their main social, ecological and financial problems? (Boege, 2003; Caro et al., 2007). In the second workshop, the recent history of resource management in a period of 20 years was discussed. The information supplied the limiting factors for the appropriation, mitigation measures, and evaluation methods for the proposals (Ortiz-Ávila & Mancera, 2008) for three TMUs defined by emic criteria; one TMU from the thinking and cultural approaches of the participants of the community, as well as two TMUs defined by ethical criteria in the work process. In the third workshop, the perception on sustainable development (World Commission on Environmental Development [WCED], 1987) through the "keyword" technique for the participatory explanation of reality (Galeano, 2007) was examined. Furthermore, 40 structured surveys were applied in order to obtain the floral composition, management and tree use of the TMUs. The surveys were supplemented with five field trips guided by local informants, verifying the presence of wild and cultivated species mentioned in workshops and surveys. The diagnosis of the TMU allows to define its conservation elements and to present alternatives to manage the incorporation of local practices to governmental regulations (Caro et al., 2007; Ross & Innes, 2006; Schiller et al., 2001).

Traditional management units

The biological and cultural conservation statuses (Toledo & Boege, 2010) of the TMU forests, LDF and traditional fruit orchards (TFO) were systematized with the combination of ethnobotanical variables as local references of the biodiversity knowledge with cultural meaning. The variables were: the mention frequency (MF) by species related to the intensity of management and the extent of the distribution of knowledge on the uses of the resource (Gheno-Heredia, Nava-Bernal, Martínez-Campos, & Sánchez-Vera, 2011), the relative cultural dominance of the families based on genus (CDG), and the relative cultural dominance of the families based on species (CDS) (Monroy-Ortiz & Monroy, 2004). Three variables were obtained from the interviews and were added to propose the value index of cultural importance (VICI):

VICI = MF + CDG + CDS

where:

MF = Mention frequency per species

Relative CDG = (Number of genera in each family/Total genera) * 100

Relative CDS = (Number of species in each family/Total species) * 100

In addition, two qualitative variables were considered: the availability of the tree species estimated by the community (ATEC) and the number of local use categories.

Participatory proposals of community conservation

The conservation proposals were generated in the workshops. The researchers collaborated with the local interests according to priority issues (Galeano, 2007; Greenwood & Levin, 2012; Ramírez-Carballo, Pedroza-Sandoval, Martínez-Rodríguez, & Valdez-Cepeda, 2011).

Results and discussion

Local organizational forms

As a result of the interviews conducted in San José de los Laureles, municipality of Tlayacapán, Morelos, two organizational forms were found: the traditional form and the community form. Traditional organization is based on the popular power characterized by the election of natural leaders for the direction of the social group, as is also reported by García-Frapolli et al. (2008). This organization represents a type of cultural resistance before the external sociopolitical interests; one of its advantages is the group of regulations related to the world view, acknowledged as a historical basis of the appropriation of nature (Weber, 1944). On the other hand, the community organization corresponds to the legal bureaucratic power comprised by a president and a supervisory board selected through an assembly among the native inhabitants, accredited by the government as owners of the common resources of the territory; through this representation they associate with the exterior. Both organizational forms correspond in order to operate the conservation policy in the protected natural area (PNA); however, just as with the rest of the country, it is faced with a contradiction. While the communities manage the resources due to their cultural importance to satisfy daily needs, the government offices adjust the changes of soil use and intensive nature extraction (Colin & Monroy, 2010).

Participatory diagnosis

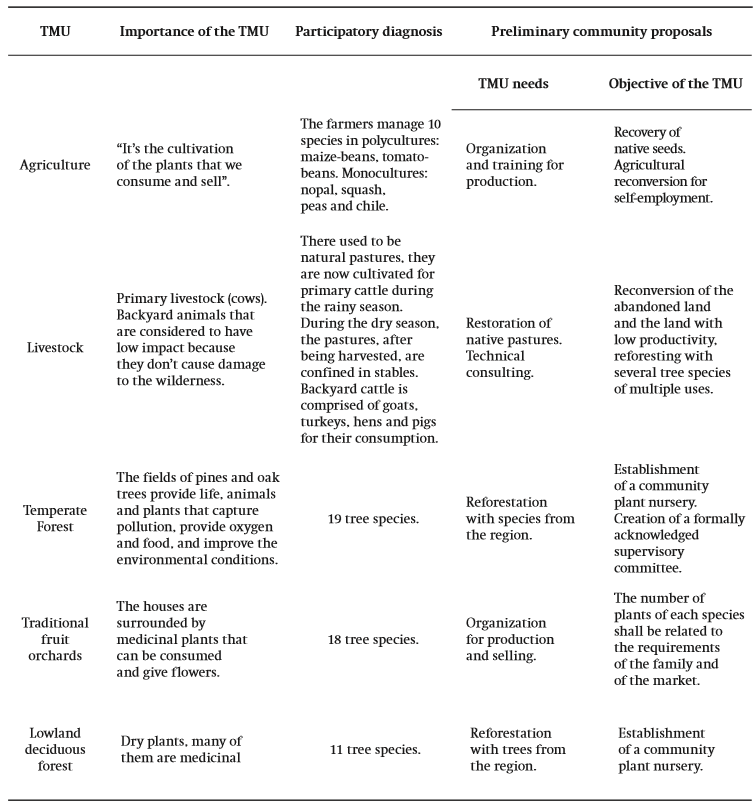

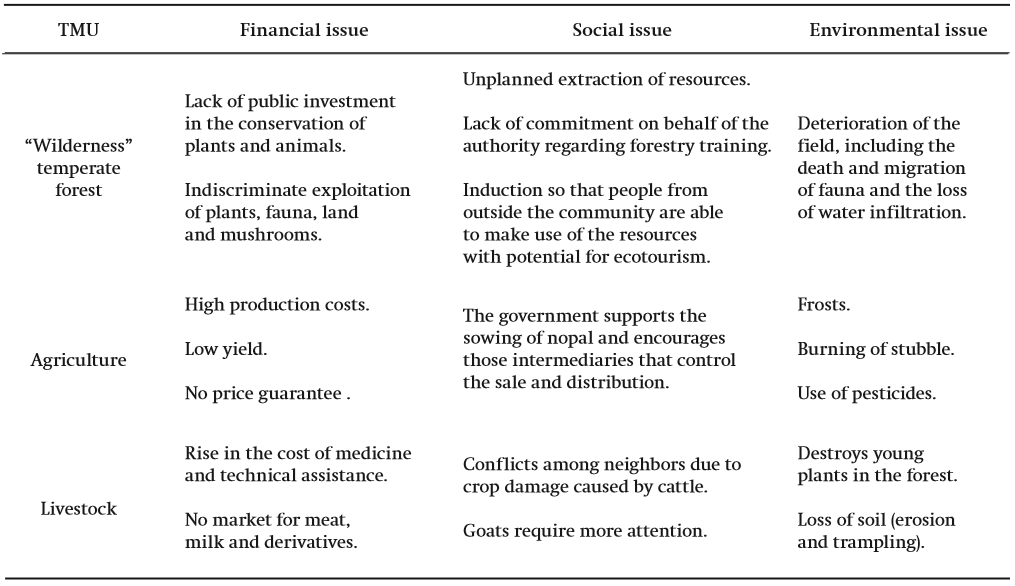

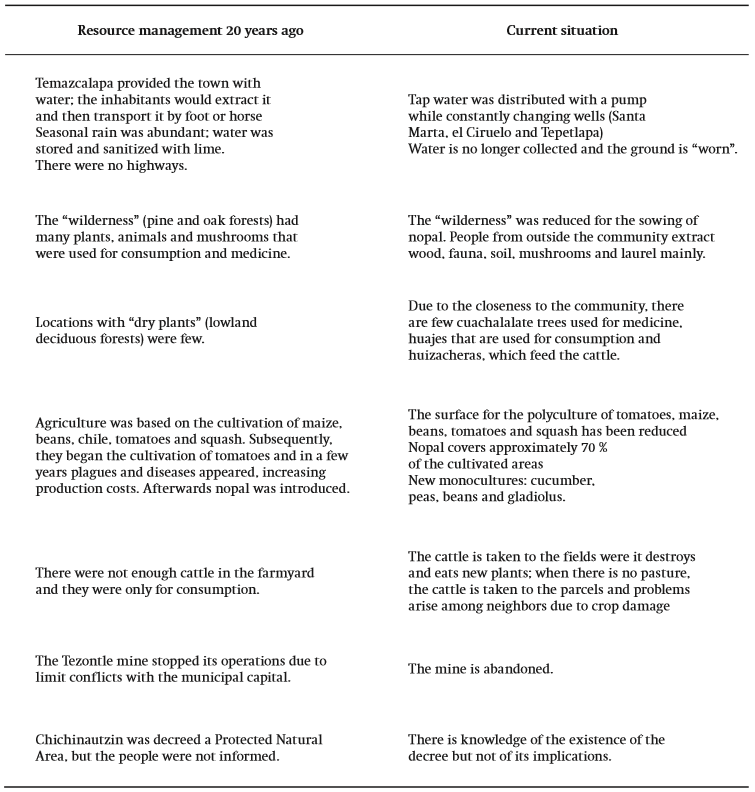

The first workshop allowed the approach of the issues with the TMUs that were identified by the community (Table 1). Due to the community's location in a PNA, problems to access the resources were found to stem from governmental regulations, to which mitigation measures and evaluation methods were presented (Table 2). The result of the second workshop was the community's perception of the change of soil use from its forest use to its use in agriculture and the loss of diversity cultivated when monocultures are predominant (Table 3), coinciding with Ortiz-Ávila and Mancera (2008), who also address the management and conservation of natural resources by rural groups.

Table 1. Traditional Management Units (TMU) and their emic issues identified in San José de los Laureles, Tlayacapán, Morelos.

Table 2. Access limitations to natural resources, mitigation measures and methods of evaluation, emic proposals in San José de los Laureles, Tlayacapán, Morelos.

Table 3. Perception of resource management during the last twenty years in San José de los Laureles, Tlayacapán, Morelos.

With regard to sustainable development, the community described it as a synonym to conservation, rescue and restoration of the "fields" with the aim of recovering the species and the exchanges of the native community. The keywords were: reforestation, education, maize, beans, elimination of waste, ecology, planting of tomatoes, and respect. Making use of these words the following sentence was formed: "The solution to the social and environmental problems should be based on education regarding 'ecology', as this will facilitate reforestation, the cultivation of maize, beans, yellow peppers, tomatoes and the conservation of water, for other activities such as farming and cleaning of the town". This diagnosis was fortified with two TMUs to add up to a total of five, including some community conservation proposals (Table 4), as suggested by Ross and Innes (2006).

Traditional management units

Agriculture. Based on the interviews conducted, 87.5 % of the respondents implement polycultures under the cornfield system, comprised of maize (Zea mays), beans (Phaseolus sp.) and tomatillo (Physalis sp.), while 57 % implement the monoculture of nopal (Opuntia sp.); however, in the maps elaborated by the community, nopal uses 70 % of the surface of the agricultural land. Farmers also sow in the form of monocultures: 50 % sow tomatoes (L. esculentum), 7.5 % sow squash (Cucurbita pepo L.) and 2.5 % sow peas (Pisum sativum L.), beans (Vicia faba L.), gladioulus (Gladiolus sp.), cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) and chile (Capsicum annum L.).

Among the respondents, 92.5 % are natives and 7.5 % residents; 60 % are co-proprietors, 22.5 % are small proprietors, 10 % tenants and 7.5 % sharecroppers (they provide 50 % of the investments and receive the same percentage in profits). For soil preparation, 90 % use metal ploughs using animal traction, which is considered a conservation indicator because it reduces the tasks and the use of heavy equipment that affects the physical characteristics of the soil such as bulk density, porosity, moisture retention, run-off and erosion (Mamani, Botello, Condori, Moya, & Devaux, 2001). The destination of the production is for self-sufficiency and direct commercialization or through third parties.

Livestock. In this TMU, 83.3 % of the respondents combine the backyard and extensive systems, while only 9.2 % practice livestock extensively, from the respondents' perception, with negative impacts on the forests and LDF (Tables 1 and 4). Furthermore, 92.5 % acknowledge the loss of native pastures and the increase in production costs.

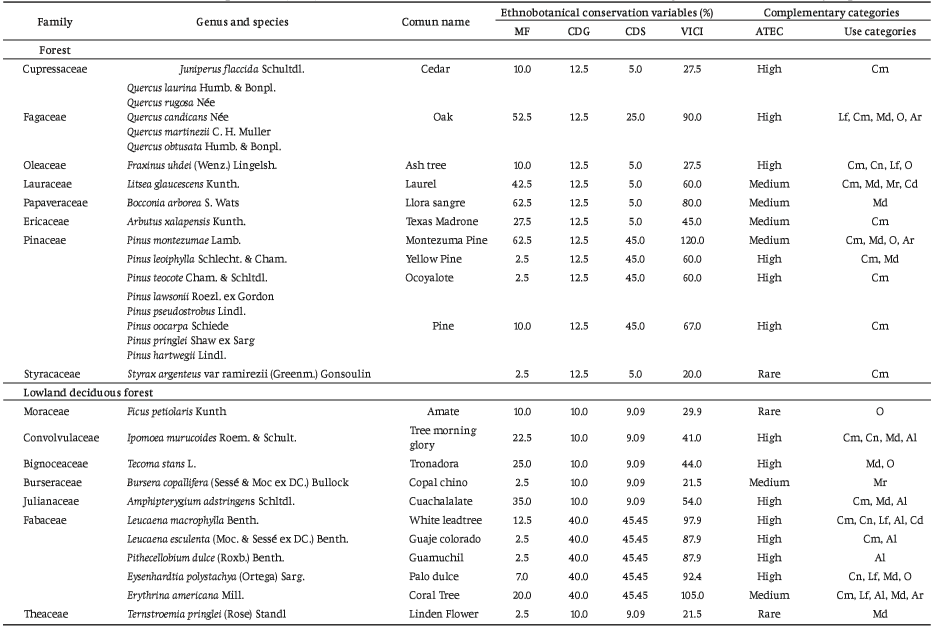

The forest. The forests and LDF are considered TMU in regards to the social work that the inhabitants develop to take hold of their components. In the forests, the community owns 19 tree species. According to the value index of cultural importance (VICI), Pinus montezumae Lamb prevails by 120 % and the Quercus spp. genus by 90 % in their five species (Table 5). According to the survey results, the ATEC values indicate that 75 % of the species have a high availability, 20 % medium and 5 % rare, the majority with a multiple use category.

Table 5. Value Index of Cultural Importance (VICI) of the forest and the lowland deciduous forests in San José de los Laureles, Tlayacapán, Morelos.

MF = Mention frequency, CDG = Cultural dominance/genus, CDS = Cultural dominance/species, VICI =Value index of cultural importance, ATEC = Availability of the species estimated by the community.

Use categories: Al = Alimentary, Ar = Artisanal, Cd = Condiment, Cm = Combustible, Cn = Construction, Lf = Living fence, Md = Medicinal, Mr = Mystic-religious and O = Ornamental.

Lowland deciduous forests. In this TMU, 11 tree species are used. The species with the highest VICI values are: Erythrina americana Mill. with 105.45 % and Leucaena macrophylla Benth. with 97 %, both with multiple uses (Table 5). The communities perceive that 63 % of the species have a high availability, 18 % have medium availability and 18 % rare availability.

Traditional fruit orchards. The orchards are comprised of a collection of 18 tree species; the ones with the highest VICI are Prunus persica (L.) Batsch and P. serotina Ehrh. subsp. capuli (Cav.) McVaugh with 67.22 and 57.22 %, respectively (Table 6), both with two use categories, the food category being primary. According to the ATEC, 55.5 % of the species were recognized as highly available, 33.3 % with medium availability and 11.1 % with rare availability.

Table 6. Value Index of Cultural Importance (VICI) of the traditional fruit orchards in San José de los Laureles, Tlayacapán, Morelos.

MF = Mention frequency, CDG = Cultural dominance/genus, CDS = Cultural dominance/species, VICI =Value index of cultural importance, ATEC = Availability of the species estimated by the community.

Use category: Al = Alimentary, Ar = Artisanal, Cd = Condiment, Cm = Combustible, Cn = Construction, Lf = Live fence, Md = Medicinal, Mr = Mystic-religious and O = Ornamental.

The temperate forests, LDF, and TFO TMUs add up to 49 tree species distributed in nine use categories, food being primary with 25.49 %, medicinal with 23.52 %, and ornamental with 16.66 %; 59.9 % of the species have multiple usages (Tables 5 and 6).

Community conservation indicators

The majority of the farmers are natives (92.5 %) that culturally resist market influence, conserving polycultures and prioritizing self-sufficiency, such as the cornfield system used by 87.5 % of the farmers; however, the threat remains as 57 % of farmers plant nopal which uses 70 % of the agricultural area. The use of animal traction is evidence to soil conservation, as 90 % of farmers use it to reduce the impact of erosion. According to Francisco-Nicolás, Turrent-Fernández, Oropeza-Mora, Martínez-Menes, and Cortés-Flores (2006), the annual loss through such management is 2,161 t∙ha-1, while using mechanical traction is 9,618 t∙ha-1. Regarding the rest of the TMU, backyard livestock is a conservationist activity developed within the TFOs, comprised of young goats, turkeys, hens and pigs destined for self-employment. In temperate forests, 75 % of the species used have high availability; species with higher VICI correspond to the Pinaceae and Fagaceae families which are the main tree components of this ecosystem. In the LDF, the community makes use of 11 species; according to the population's perception 63 % have high availability, coinciding with the rate of species with multiple uses. Those with higher VICI are: E. americana and L. macrophylla, both originating in Mexico with wild and cultivated management. In the TFO, conservation is defined as 88.8 % of the plants are available in their different categories of use, mainly in the food category. There is also a clear homogeneity of VICI in the 18 species.

Participatory proposals of community conservation

Some of the proposals are the promotion of the use of animal traction for the soil conservation and the establishment of sample cornfields that reproduce and give feedback to 87.5 % of the producers, which would reduce the impact on agro-diversity caused by the sowing of nopal in the area. Furthermore, it is considered that extensive cattle farming should be bred in drylots; it is also urgent to encourage the less integrated breeding of pigs, hens and turkeys associated to TFO, which is destined for self-consumption and therefore important for local nutrition. In the case of temperate forests and lowland deciduous forests, a project of agro-ecology was presented in order to boost the restoration of native species with cultural importance, a proposal that coincides with the Foro de Consulta a los Pueblos y Comunidades Indígenas de Morelos (FCPyCIM, 2010). All the proposals will be strengthened with the design of a training program that will boost the restoration, transmission and feedback of the local knowledge of the area of the TMUs that were studied.

Conclusions

The traditional and community organizations should coexist. The traditional organization is effective because its cultural regulations provide independence to the foreign parties that promote the change of soil use, cancelling the social reproduction of the TMUs and community organizations are necessary for exchanges with the exterior. The participatory diagnosis was useful to systematize the factors that limit the appropriation of resources, their mitigation measures and the conservation indicators synthesized in the VICI of the TMU. In addition, the VICI quantitatively summarized the frequency of mention of the plants, the cultural dominance by genus and species, the record of availability of each species and their use. The conservation indicators were the base of the participatory proposals, facilitating the reversal of the information. During the work, the rights of the native towns were socialized; however, the results were not influenced by the fact that the community is immersed in a protected natural area, due to the fact that the majority of the inhabitants do not have this information and if they have any knowledge about it they do not admit it. Finally, it is concluded that the conservation of TMUs is essential because the users reproduce the knowledge regarding resource management, which suggests that they are replicable in analogous socio-environmental conditions.

texto em

texto em