Introduction

Habitat loss is most often perceived to be caused by discernibly drastic factors such as clear-cutting of forest for the expansion of agriculture (Andren 1997). In contrast, a more subtle, transformative pressure on vegetation communities is “woody plant encroachment” (WPE; Archer et al. 2017), also known as the “thicketisation” of grasslands (Archer et al. 1995). This phenomenon of WPE has increased worldwide over the past century, albeit at different rates in different continents (Sankaran et al. 2005; Sala and Maestre 2014; Archer et al. 2017; Stevens et al. 2017; 2020 Garcia-Criado et al. 2019). Despite its ecological relevance, there is a general recognition of the complexity in identifying the main causative drivers for this phenomenon; especially since variations in time, land-use history and bioclimatic zones need to be taking into account (Van Langevelde et al. 2003; Sankaran et al. 2005; Kulmatiski and Beard 2013; Archer et al. 2017). Furthermore, WPE-driven reshaping of the physiognomy of grasslands and savannas (Kenoyer 1929; Van Auken 2000; Scheffer et al. 2001; Graz 2008) has effectively resulted in their overall depletion of these habitats with associated declines in plant species richness (Ratajczak et al. 2012), or their degradation (Baez and Collins 2008). In addition, the specific consequences for ecosystem function and biodiversity are variable (Barger et al. 2011; Eldridge et al. 2011) from overall declines across trophic levels to expansion or reduction of specialist species ranges, among many other changes reviewed by Garcia-Criado et al. (2019). Furthermore, WPE could be a significant pressure on both grazing and browsing herbivores, causing perhaps reductions in forage value (Eldridge et al. 2011), and therefore transforming the structure of the vegetation communities that make up their habitats.

As stated by Archer et al. (2017) very little is known regarding specific responses of animals to WPE-driven habitat transformation. There are a few studies relating habitat transformation to different components of biodiversity such as birds (Knopf 1994; Coppedge et al. 2001; Skowno and Bond 2003; Coppedge 2004; Cunningham and Johnson 2006; Sirami et al. 2009; Block and Morrison 2010; Sirami and Monadjem 2012), arthropods (Steenkamp and Chown 1996; Blaum et al. 2009), and reptiles (Mendelson and Jennings 1992; Meik et al. 2002; Pike et al. 2011). However, to the best of our knowledge, there are only around a dozen specific studies on the consequences of shrub encroachment on mammals in general (Kavwelle et al. 2017). Examples of the latter are, specifically rodents (Blaum et al. 2007a; Emmons 2009; Bilney et al. 2010; Pardiñas et al. 2012; Pardiñas and Teta 2013), carnivores (Blaum et al. 2007b), and ungulates (Okello 2007; Kimaro et al. 2019). Among the latter, only a few have explored the disruption caused by WPE on mammalian species dependent on relatively open areas such as grasslands and savannas (Krogh et al. 2002; Blaum et al. 2007a).

In South America, one of the largest native mammalian herbivores, strongly associated with grasslands, with the exception of the cold forests in Tierra del Fuego (Muñoz and Simonetti 2013), is the guanaco Lama guanicoe (Miller et al. 1973; Franklin 1982, 1983; Travaini et al. 2007). Despite guanaco presence in four of the ten major ecoregions described in South America, the distribution range of this species has contracted by 60 % during the last century (Gonzalez et al. 2006). The situation is further exacerbated with local extinctions and isolation of guanaco populations within its current distribution range (Miller et al. 1973; Sosa and Sarasola 2005; Gonzalez et al. 2006; Cuellar-Soto et al. 2017a; Cook-Mena et al. 2019). Strikingly, despite the latter, the guanaco continues to be categorized as of least concern (LC) by the IUCN (Baldi et al. 2016). However, three (Perú, Bolivia and Paraguay) of the five countries that acknowledge this incongruity have changed the guanaco’s conservation status to Endangered (EN) and Critically Endangered (CR; Cuéllar and Núñez 2009; Cartes et al. 2017; SERFOR 2018).

In Bolivia, we studied the relict and isolated population of around 200 Chacoan guanacos, which constitutes the north-eastern fringe of the species range (Cuéllar and Núñez 2009). At the same time, this population is restricted to an area characterized by a mosaic of vegetation in different stages of the WPE process, with variations in height (0.4 to 4 metres) and thickness (Navarro and Fuentes 1999; Pinto and Cuéllar-Soto 2017).

We tested differential use of habitats at different stages of WPE by guanacos in relation to their availability, both at a landscape and home range scale. Although guanacos are considered as generalist herbivores (Raedeke and Simonetti 1988; Puig et al. 2001; Puig et al. 2011), we hypothesized that guanacos prefer native grasslands and the early stages of encroachment together with the remaining of native grasslands over other available habitats. Finally, we hypothesised that WPE is causing contraction of potential suitable habitat for the Chacoan guanacos.

Materials and Methods

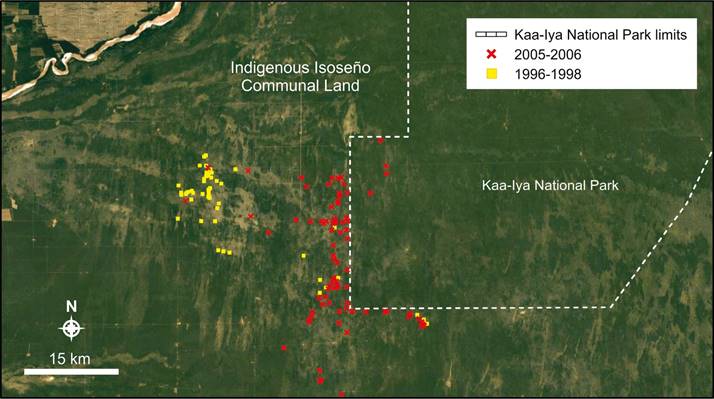

The study area extends from -19° 45’ to 20° 30’ S and from -62° 00’ to 63° 00’ W, on the fluvial megafans of the Río Grande and the Río Parapetí in the Bolivian Gran Chaco (May et al.2008), in the extreme south of Santa Cruz department, Bolivia. The study area includes the southwest corner of the Kaa-Iya National Park and part of the Indigenous Isoseño Communal Land (Figure 1). The climate is predominantly semi-arid (Peel et al. 2007), with annual rainfall ranging from 200 to 350 mm (Taber et al. 1997).

We used the information on the expansion of each vegetation community from the vegetation maps produced by Pinto and Cuéllar-Soto (2017b). The latter is based on Navarro’s classification of stages of WPE in the study area (open forest, thick woodland, shrubland, scrubland, grassland) according to their structure (0.40 to 4 metres), species composition and cover (Navarro and Fuentes 1999).

The total area covered by our aerial surveys (Figure 2) was the potential guanaco range. We defined the latter by taking into account: 1) earlier guanaco observations and interviews with local people (Villalba 1992; Emmons 1993; Anderson 1997; Cuéllar and Fuentes 2000), and 2) the potentially suitable habitats, including all main expansions of savannahs and relatively open vegetation on sandy soil covering around 3,000 km² (Cuéllar and Fuentes 2000). In addition, we compared the observations gathered in a specific area, between 1996 and 1998 (Miserendino et al. 1998; Weber 2000), to those collected between 2005 and 2006 to confirm retraction in part of the guanacos’ local distribution range.

At the landscape level, we determined the distribution of guanacos from aerial surveys in April 1998, December 2001 and December 2004, and confirmed in subsequent aerial surveys (2008 and 2011). We used a single-engine light aircraft (Maule ML5) during peak periods of guanaco foraging activity (early morning from 6 to 8 AM) when guanacos were most likely to be visible and hence detected. We maintained a constant height of approximately 100 m above ground level at an average speed of 180 km/hr along fixed-width strip transects (450 m to each side of the aircraft), oriented north-south. We defined the “usage” of habitat as a given area at a radius of 450 m around each guanaco observation point from the plane. Determination of this area was resolved using either side of the aerial transect as a measure, together with the visibility we had from the plane. In addition, we defined as habitat availability the total area during the first aerial survey.

Figure 1 The study area is in the extreme south of the Santa Cruz department of Bolivia and less than 100km from the Paraguayan border. It is part of the Indigenous Isoseño Communal Land and includes the southwest corner of the Kaa-Iya National Park.

On a fine scale, for the purposes of analysis, we selected the information gathered for only six distinct guanaco groups tracked for twenty months (between 2007 and 2009) and recorded the habitat used within their approximate home ranges. These small groups of between two to four adults with one or two newborns or sub-adults (Table 1), remained in the same general area throughout the year. Group composition did not vary during the monitoring period. We identified groups from variations in phenotypical traits and morphological characteristics such as scars, fur colour variations in males, and group composition (Cuéllar and Noss 2014) - an approach similar to that used to identify other species with subtle differences in skin patterns, such as puma Puma concolor (Kelly et al. 2008). We used roads and trails as fixed transects crossing different habitats within the vegetation mosaic. Mean transect length, travelled on foot or on horseback, was 10.5 km (range: 7 to14 km). Locations of identified guanacos were recorded and mapped using ArcView (Environmental Systems Research Institute, Redlands, USA). Minimum home ranges (utilized habitats) were estimated using Minimum Convex Polygons (sensu Mohr 1947) and Animal Movement Analysis Extension (Hooge and Eichenlaub 1997). Using Ranges7 software (South et al. 2005), we determined the core area (Kernel 99 %) of the guanaco population from cumulative observations and determined it as available habitats.

At both scales [1) the landscape level, habitat within the 450 m radius buffer around each observation location versus total area surveyed with the aircraft. And 2) the fine scale, home ranges versus core area of the study population] we performed a Manly-Chesson’s index referring to the standardised proportional use of each habitat divided by its proportional availability, so the values for all habitats sum to 1 (Manly et al. 1972; Chesson 1978). An index value < 1 or > 1 suggesting, respectively, that the habitat is avoided or selected.

Finally, we plotted the observations recorded in two periods, the first between 1996 and 1998 and the second between 2005 and 2006. Data was gathered using the same methodology (by foot or on horseback) and by the same core of observers on a map including the borders of the newly created Kaa-Iya del Gran Chaco National Park.

Results

We estimated the Chacoan guanaco range to be less than 800 km2 from the approximately 3000 km² potentially available in 1998. The same broad distribution was confirmed 13 years later by subsequent aerial surveys (2001, 2004, 2008, 2011) and in 2020 by monthly reports of the Kaa-Iya National Park para-biologists and park rangers.

Figure 2 The total area covered by the aerial surveys. The total area covered by our aerial surveys (in grey). This area surveyed represents the potentially suitable habitats on sandy soil covering around 3,000 km².

At a landscape level, the proportions of habitat categories available in the landscape versus proportions utilised (within a 450 m radius of observations during aerial surveys) are presented in Table 2. In addition, Manly-Chesson index values suggested consistent patterns in use of the study area by guanacos (Figure 3). Index values calculated for the three aerial surveys (1998, 2001, and 2004) were each >1 indicating that the combination of scrubland and grassland was the favoured habitat type over shrubland, thick woodland and open forest.

Table 2 Landscape level analysis: Proportions of habitat categories available in the landscape versus proportions utilized (within a 450m radius of observations during aerial surveys).

| Habitat type | Available % (1998) | Mean % habitat use | Available % (2001) | Mean % habitat use | Available % (2004) | Mean % habitat use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Forest | 30.8 | 2.5 | 19.0 | 13.0 | 41.2 | 6.2 |

| Thick woodland | 10.9 | 2.3 | 15.9 | 7.6 | 11.0 | 3.2 |

| Shrubland | 23.0 | 20.8 | 34.1 | 21.9 | 21.9 | 14.5 |

| Scrubland+Grassland | 35.3 | 74.26 | 35.4 | 57.5 | 25.9 | 76.1 |

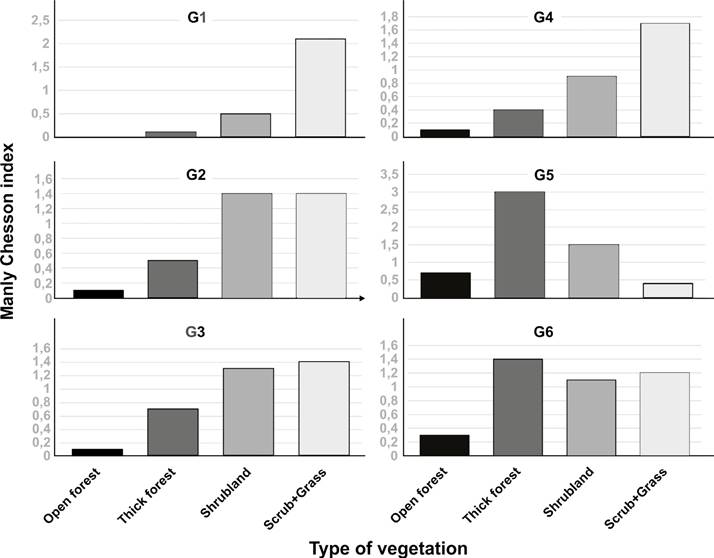

At a fine scale, the mean home range of these guanaco groups, which maintained constant familial compositions throughout the study period, was 24 km2 (± 14 SD; N = 6, range: 13 to 51 km2; Cuéllar and Noss 2014). The proportions of habitat categories available within the guanaco population core area versus proportions within minimum convex polygon (MCP) - approximate home ranges- of six guanaco groups are presented in Table 3. Manly-Chesson index values were not consistent between groups and are presented in Figure 4. In fact, the index value was >1 for only two (G1 and G4) of the six groups, with a scrubland/grassland type habitat combination clearly favoured by these two groups over other available habitat types (shrubland, thick woodland and open forest). In contrast, the index value for group five (G5) suggested preference for shrubland and thick woodland. Two groups (G2 and G3) showed preference for the combination of scrubland and grasslands plus shrubland with the remaining group (G6) only showing avoidance for open forest.

When records from two periods were plotted, we observed a contraction in part of the local distribution towards the Kaa-Iya National park border, between 1996-1997 and 2005-2006 (Figure 5), the latter confirming the comments from local ranchers.

Figure 3 Manly-Chesson index values for the three aerial surveys (1998, 2001 and 2004) suggested consistent patterns in use of the study area by guanacos. Index values >1 indicates that the combination of scrubland and grassland was the favoured habitat type over shrubland, thick woodland and open forest.

Discussion

This study is the first investigation on use of habitat by a relict population of guanacos in the Bolivian Gran Chaco. First, our results supported the prediction that, at a landscape scale, guanaco showed preference to areas where the early stages of woody plant encroachment were relatively low. The latter is not surprising since a previous study showed that Chacoan guanacos are largely pastoral (Cuéllar-Soto et al. 2017b). However, these grassy areas, consisting mainly of communities of the native grass Aristida mendocina (Poaceae), are themselves disappearing due to different stages of WPE (Pinto and Cuéllar-Soto 2017), starting with the gradual replacement of A. mendocina by an invasive forb Lippia sp. (Navarro 2002). Therefore, if the overall purpose on evaluating habitat use is to understand the basic requirements to sustain this population of guanacos, we need to highlight the poor quality and acute regression of the current preferred habitat. In this case, habitat structure can have a profound effect on recovery success of the guanaco population and its long-term establishment. On one hand, the loss of suitable habitat could affect food availability for guanacos, owing to the replacement of palatable plants by unpalatable woody species and annuals as previously reported from studies in South Africa (Chambers et al.1999), Australia and the United States of America (Janssen et al. 2004). On the other hand, effective detection of predators can be impeded by WPE through deteriorations in guanaco visibility (e. g.Riginos and Grace 2008; Underwood 1982). Therefore, WPE is likely to have a negative effect on the ability of guanacos and other species living in open environments, reliant on sight, to detect predators (Kunkel and Pletscher 2000; Barri and Fernández 2011; Flores et al. 2012). In addition, Bank et al. (2002) reported that puma kills on guanacos were significantly more frequent in habitat with dense cover (mainly shrubland) and suggested that guanacos’ selection for open and flat terrain is a critical component of their predator avoidance strategy and long-term survival. Similarly, Owen-Smith (2008) argued that shorter grass height can reduce the predation vulnerability of wildebeest Connochaetes taurinus and zebra Equus burchelli in Africa.

Figure 4 Manly-Chesson index values for the six groups (G1, G2, G3, G4, G5, and G6). The index value >1 for scrubland/grassland type habitat combination clearly showed that G1 and G4 favoured that available habitat types over shrubland, thick woodland and open forest. G5 suggested preference for shrubland and thick woodland, and G2 and G3 showed preference for the combination of scrubland and grasslands plus shrubland. G6 only showed avoidance for open forest.

Furthermore, we observed some differences at a home range scale in the use of habitat among the groups. The index values for G1, G2, G3 and G4, suggested that the combination of scrubland and grassland habitat type was favored over shrubland, thick woodland and open forest. Interestingly, those groups had the highest numbers with either a newborn or subadult as part of the family group. In contrast, G5 and G6 were groups of two couples without offspring. This latter point could raise the question as to whether habitat preference is more notably linked to reproduction and survival (Garshelis 2000), so, in effect, does our observed pattern suggest a limitation of the current mosaic for supporting population growth? If true, can we assume that the guanaco population in question is under risk of early extinction? To help answer this question additional information and monitoring data acquired from recent technological advances and field equipment is required. This may involve the use of expandable GPS collars for subadults to assess individual patterns of dispersion following expulsion from the family group. However, any attempt to capture and tag Chacoan guanacos should consider the current situation of such a small and fragile population and the risk of having animals escaping into dense vegetation and or barb-wired borders of private ranches, at a risk to themselves. Given the low visibility and the small chances to encounter the guanacos, which is extremely contrasting to any other population studied on the continent (Cunazza et al. 1995; Baldi et al. 2009; Sosa and Sarasola 2005; Arzamendia et al.2006; Puiget al.2008; Cassiniet al. 2009; Acebes et al. 2010; Burgi et al. 2011a b; Parreño et al. 2001; Flores et al. 2012; Cook-Mena et al. 2019; Puig et al. 2019), the use of horses is recommended. Furthermore, researchers should expect to invest a lot of physical effort and time, including travelling long distances over several days and rough terrain without observing any guanacos.

Table 3 Fine scale analysis: Proportions of habitat categories available within the guanaco population core area versus proportions within minimum convex polygon (MCP) home ranges of six guanaco groups.

| Habitat type | % habitat available | MCP 1 | MCP 2 | MCP 3 | MCP 4 | MCP 5 | MCP 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Forest | 25.0 | 0.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 2.3 | 18.9 | 7.9 |

| Thick woodland | 9.5 | 1.0 | 4.7 | 6.9 | 3.7 | 29.4 | 13.5 |

| Shrubland | 24.6 | 12.3 | 34.9 | 32.8 | 23.3 | 36.9 | 28.8 |

| Scrubland+Grassland | 40.7 | 86.5 | 57.3 | 56.3 | 70.5 | 14.6 | 49.5 |

In addition, on both scales, our results showed that guanacos were concentrated within the same broad range and within the most open areas, suggesting that this guanaco population is sedentary. According to Franklin and Fritz (1991) guanacos can be sedentary or migratory in response to food availability. However, there is no suitable habitat into which guanacos can expand their range unless effective management interventions are implemented on the respective ranch properties, indigenous communal lands, and a portion of the Kaa-Iya National Park currently occupied by the guanacos. At present, almost the entire guanaco population is restricted to private lands and indigenous communal land. On one hand, the private lands are mainly cattle ranches with evident degradation of pasture and invasion by woody plants (Angulo and Rumiz 2009). On the other hand, and with a more promising prospect, there has been a recently approved municipal law (“Ley autonmica No 034/2019 ley de creación, conservación del Área de Vida del Guajukaka (guanaco) en la Zona Alto Isoso (AVIGUZI ) y Protección del Guajukaka (guanaco) en Charagua Iyambae”) declaring an area of 2,500 Km2 as a municipal reserve for guanacos. The latter will encourage further efforts for the protection of the species.

Second, our results also supported the prediction that WPE is causing a contraction of potential suitable habitat for the Chacoan guanacos. We observed a contraction in the area previously occupied by the species (Miserendino et al. 1998; Weber 2000) which could be the beginning of a distributional shift and potential loss of the guanaco’s geographic range due to habitat replacement, as has been suggested for past geographic distributions of the species in Argentina (Tonni and Politis 1980; Barberenaet al.2009). The most obvious explanation for this contraction is the intensive development of a cattle ranch in the area (Angulo and Rumiz 2009). In addition, given the general strong association between guanacos and their preferred open habitats (Travaini et al. 2007), together with the reduction by 90 % of grasslands due to WPE (Pinto and Cuéllar-Soto 2017), could be engendering a setback for the long-term survival of the guanaco population under study. There are cases where long-term changes in the structure and composition of grasslands have bolstered declines of small mammal communities (Emmons 2009; Bilney et al. 2010; Pardiñas et al. 2012; Pardiñas and Teta 2013).

Figure 5 The comparison between the records gathered in two periods (1996-1998 and 2005-2006) showed a retraction in the distribution of the local Chacoan guanaco population towards the Kaa-Iya National Park border.

Even though we are concerned by the multiple factors, such as cattle ranching, change in fire regime (severity and frequency), and soil erosion, driving woody plant encroachment (Morello and Adamoli 1974; Devineet al.2017), we urge for a particular focus on conservation efforts in countering consequences of WPE (Midgley and Bond 2001; Moncrieff et al. 2009; Kgopeet al.2010; Cipriotti and Aguiar 2012). Therefore, we appeal to researchers and decision makers to look beyond the more obvious human-induced pressures on the species (including hunting, competition with domestic livestock and habitat loss or fragmentation resulting from agricultural development; Cunazzaet al. 1995) and consider the importance of WPE as a direct driver for habitat loss (Wigley et al. 2010).

Furthermore, we encourage managers of the 2,500 km2 reserve, recently created by the Indigenous Autonomous Government of the Bolivian district of Charagua, to adapt their management interventions and conservation strategies, and take into consideration this silent but pernicious process of “thicketisation” of savannahs and grasslands. Finally, we encourage and promote the development of additional studies on this phenomenon given that it could constitute an imminent threat to the region’s biodiversity (Archer et al. 2017).

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)