Introduction

In the Neotropics, bats represent the most diverse group amongst mammals (Vaughan 1997; Medellin et al. 2000; Sampaio et al. 2003; Bracamonte 2011), showing the greatest variety of dietary habits; this flexibility accounts for the morphological, physiological, and ecological complexity of this group (Altringham 2011). Bats of the genus Platyrrhinus (Phyllostomidae) are frugivores that play a key role in seed dispersal and the redistribution of nutrients (Medellin 2003; Velazco and Gardner 2009; Estrada-Villegas et al. 2010).

In recent decades, a number of studies have confirmed the role of this genus in forest succession and ecological restoration, because they consume pioneer species and are among the most important seed dispersers in fragmented and early successional ecosystems (Galindo-González et al. 2000; Marques and Fisher 2009; Castro-Luna and Galindo-González 2012; García-Herrera et al. 2019). Therefore, the species of this genus have the potential to provide functional services to the environment because they disperse large amounts of seeds in Neotropical forests.

The genus Platyrrhinus includes 20 recognized species, representing one of the most diverse genera within the family Phyllostomidae (Redondo et al. 2008; Velazco and Patterson 2008, 2014; Velazco and Lim 2014; Velazco et al. 2018), only surpassed by the genera Sturnira with 24 species (Velazco and Patterson 2014, 2019) and Artibeus with 23 species grouped into two subgenera (Artibeus and Dermanura;Cirranello et al. 2016; Velazco and Patterson 2019). In Colombia, Platyrrhinus is represented by 14 species (Ramírez-Chaves et al. 2016), with geographic and altitudinal ranges that vary widely (Velazco and Solari 2003; Gardner 2008; Velazco and Gardner 2009). As part of the most recent IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) Global Mammal Assessment, three species of Platyrrhinus are listed as Threatened (Platyrrhinus chocoensis, VU, P. ismaeli and P. matapalensis, NT).

Platyrrhinus ismaeli lives mainly in lowland and montane forests (Tirira 2011). The high rate of habitat destruction throughout the tropical Andes may soon cause P. ismaeli to be assigned to the Near Threatened (NT) category (IUCN 2019), thus highlighting the importance of generating in-depth information on the geographic distribution and status of their populations, which is needed to advance conservation actions.

In Colombia, P. ismaeli has been recorded in 26 localities along the Andes (Velazco and Gardner 2009); these include eigth localities in the western range (Departments of Risaralda and Valle del Cauca), nine in the central range (Departments of Antioquia, Cauca, Huila, Putumayo, and Quindío), and nine in the eastern range (Departments of Boyacá, Caquetá, Cundinamarca, Norte de Santander and Meta). Records in Colombian collections support that P. ismaeli inhabits a wide variety of habitats within an altitudinal gradient of 1,230 to 2,950 m (Muñoz 2001; Solari et al. 2013). Although this species seemingly prefers high-montane forests (Table 1), there are some records of P. ismaeli in the foothills of the western range, in the eastern side of the Department of Chocó, suggesting that it also inhabits the premontane very humid forest (Asprilla-Aguilar et al. 2016).

The distribution range reported for this species comprises the eastern slope of the central range (Departments of Nariño and Tolima), the eastern range (Departments of Santander and Casanare), and the low montane forest and low montane wet forest of Colombia (according to Holdridge 1987 system, Table 1), which are highly fragile and threatened ecosystems for impacts related to human activities. Accordingly, we analyzed the potential distribution of P. ismaeli, provide cranial measurements and information on the life zones for the new localities (Tables 1, 2, Figure 1, 2, Appendix 1), and discuss the scenarios that might determine the distribution of this species in Colombia. Our objectives were: to predict the current potential distribution, and to identify the key environmental factors that are highly correlated with the distribution range of P. ismaeli. This information sets the basis for generating data for the conservation of this species, needed to face the current habitat loss and fragmentation issues, and other impacts to the life zones of populations of this species in Colombia.

Materials and Methods

The main sources used for this update included research articles, taxonomic revisions, and direct examination of the zoological collections of the University of Tolima (CZUT-M, Ibagué), Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH-M, Villa de Leyva), Instituto de Ciencias Naturales at Universidad Nacional de Colombia (ICN, Bogotá), and Universidad del Valle (UV, Cali). Secondary sources include records available in the online databases of the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution (NMNH; VertNet), and cataloged specimens reported in regional checklists (for example, Asprilla-Aguilar et al. 2016; Jimenez-Ortega 2013). For specimens to which we had direct access, we took external and cranial measurements with digital calipers to the nearest 0.1 mm (Table 2). Data on total length (TL) and weight (W) were obtained from specimen labels, recorded at the time of collection.

We reviewed all available specimens housed at the CZUT-M, searching for vouchers of P. ismaeli. Based on our review, and because they were suspected of being misidentified, we also included four specimens formerly identified as Vampyrops aurarius (Bejarano-Bonilla et al. 2007), plus another identified as P. aurarius by Galindo-Espinosa et al. (2010), and five Chiroderma salvini (identified by Galindo-Espinosa et al. 2010). To assess the accuracy of their identifications, we compared each specimen with the characters provided by Velazco (2005) and Velazco and Gardner (2009), and described the morphological characters, external, and cranial and dental measures of P. ismaeli distributed in Colombia.

Data sources and selection of variables. In order to elaborate the checklist, we reviewed and gathered occurrence data from P. ismaeli records in museum collections in Colombia (CZUT-M, ICN, IAvH-M, UV, and NMNH. Including: coordinates, elevation, locality, geographic region, and life zone according to the classification of Holdridge 1987; Table 1), confirmed by reviewing the morphology and taxonomic identification of specimens (Velazco 2005; Velazco and Gardner 2009), as well as from records reported in the scientific literature. Occurrence localities from specimen tag data were then thoroughly georeferenced (i. e., for those lacking field GPS readings; Sánchez-Cordero and Guevara 2016). To reduce issues associated with spatial sampling biases (Merow et al. 2013; Boria et al. 2014), we spatially thinned our original dataset consisting of 38 localities using the spThin package in R (Aiello-Lammens et al. 2015).

Table 1 Records of Platyrrhinus ismaeli in Colombia used for modeling the potential distribution of the species. Life zones: A) low montane humid forest, B) low montane very humid forest, and C) premontane very humid forest. Regions: Central Range (CR), Eastern Range (ER), and Western Range (WR); Vereda (Ver); Life zone (LZ).

| Voucher | Latitude | Longitude | Elev. | Municipality | Department | Region | LZ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICN 16503 | 5.5882 | -75.9294 | 2,010 | Andes,Ver. La Soledad | Antioquia | CR | A |

| ICN 17165 | 6.1654 | -74.3173 | 1,860 | Santa María, Ver. Caño Negro | Boyacá | ER | C |

| ICN 15066 | 4.9667 | -73.3440 | 1,269 | Santa María, Margen izquierda río Batá | Boyacá | ER | C |

| ICN 16352 | 4.9443 | -73.3252 | 1,259 | Santa María, Sitio Represa Chivor. | Boyacá | ER | C |

| ICN 5441 | 5.3066 | -72.7138 | 1,970 | Pajarito, Hacienda Camijoque. | Boyacá | ER | C |

| ICN 19320 | 5.4166 | -71.2750 | 1,085 | Trinidad, Banco de la Cañada | Casanare | ER | C |

| MHNUC 1467, 1501; USNM 483575 | 2.4010 | -76.1306 | 2,638 | Moscopas, 1 Mi N Moscopas | Cauca | CR | A |

| ICN 8467, 8468 | 2.5518 | -76.0912 | 2,253 | Inza, Ver. Tierras Blancas, Km. 78 carril Popayan | Cauca | CR | A |

| CMCH 1136 | 5.8982 | -76.1487 | 2,950 | El Carmen de Atrato | Chocó | WR | A |

| ICN 5293, 5295 | 4.6830 | -74.3894 | 1,870 | Tena, Laguna de Pedro Pablo | Cundinamarca | ER | C |

| FMNH 58732, 58733, 58734, 58735, 58736, 58737, 58738. | 2.0178 | -75.7459 | 1,100 | Parque Natural Nacional “Cueva de los Guacharos” | Huila | CR | C |

| IAvH-M 1930, 1932, 1934, 1990,1992, 1994, 1996. | 1.6000 | -76.1301 | 2,800 | Parque Natural Nacional “Cueva de los Guacharos”. Puente superior en Río Suaza | Huila | CR | A |

| ICN 13087 | 11.1430 | -73.8282 | 1,050 | Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Alto de Mira, 3 Km W Río Buritaca. | Magdalena | C | |

| ICN 14372 | 4.2749 | -73.5874 | 1,090 | Restrepo, Salinas de Upin | Meta | ER | C |

| ICN 14800 | 3.8262 | -73.8435 | 1,000 | Cubarral, Ver. Aguas Claras | Meta | ER | C |

| Jiménez Ortega | 1.6812 | -78.1417 | 1,004 | Barbacoas | Nariño | WR | C |

| IAvH-M 6681, 6682 | 7.2584 | -72.2259 | 1,608 | Toledo, Ver. San Isidro | Norte de Santander | ER | C |

| ICN 21022 | 1.1336 | -76.6328 | 2,000 | Mocoa, El Mirador | Putumayo | CR | A |

| IAvH-M 6818, 6823 | 1.0715 | -76.7353 | 1,922 | Mocoa, El Mirador | Putumayo | CR | C |

| ICN 12476 | 4.6706 | -75.6179 | 1,975 | Finlandia, Ver. El Roble | Quindío | CR | C |

| ICN 12448 | 4.6834 | -75.5244 | 2,634 | Salento, Reserva Natural Cañon Quindio, frente de reforestación Monte Loro | Quindío | CR | A |

| UV 12694 | 4.7299 | -75.5766 | 2,250 | Quimbaya, Ver. La Suiza | Risaralda | ER | A |

| ICN 8150, 8972, 8973 | 6.0967 | -73.2036 | 1,790 | Charalá, Margen derecho del Río Guillermo | Santander | ER | C |

| ICN 17585, 17586, 17587 | 6.4535 | -72.8266 | 2,013 | Encino, Vereda Río Negro, Las Tapias, finca El Aserradero. | Santander | ER | A |

| ICN 16660, 16661 | 7.1333 | -72.9941 | 2,150 | Tona, Ver. Guarumales, finca El Pajal. | Santander | ER | A |

| ICN 12448 | 7.1334 | -72.9832 | 1,800 | Tona, Sitio El Mortiño, carretera Bucaramanga-Cúcuta Km 18. | Santander | ER | C |

| CZUT-M 58. | 4.4258 | -75.3697 | 1,557 | Cajamarca, Ver. Peñaranda parte Baja | Tolima | CR | C |

| CZUT-M 83, 84, 144, 145. | 4.4830 | -75.4532 | 2,055 | Cajamarca, Ver. Planadas | Tolima | CR | A |

| CZUT-M 208, 317. | 4.3865 | -75.3417 | 2,084 | Cajamarca, Ver. El salitre | Tolima | CR | A |

| CZUT-M 57. | 4.5440 | -75.4204 | 2,398 | Ibagué, Ver. Toche | Tolima | CR | B |

| CZUT-M 206, 207 | 4.5000 | -75.3000 | 1,777 | Ibagué, Quebrada La Plata | Tolima | CR | C |

| UV 12402, 12403, 12405, 12407, 13022, 13023. | 3.8920 | -76.2800 | 1,124 | Buga, Ver. El Janeiro | Valle del Cauca | WR | C |

Nineteen variables were retrieved as predictors to model the potential environmental niche of P. ismaeli based on the current presence dataset in 15 different localities (Velazco and Gardner 2009; Table 1), plus other available records. In particular, 19 bioclimatic layers (Table 3) and one topographic variable (elevation) were obtained from the WorldClim version 2 database (WorldClim: Global Climate Data 2017; Hijmans et al. 2005) at a spatial resolution of 30 arc-second (ca. 1 × 1 km). Elevation, slope, and aspect data were extracted using ArcGIS 10.4.1. The overall environmental variables are summarized in Table 3. In order to eliminate multicollinearity and select the most fitting predictors that show more contribution power to the model, Variance Inflation Factors (VIFs) of 22 environmental variables were tested. VIFs are based on correlation coefficients (R2) estimated from regressions for all predictors, implemented through the ‘sdm’ package in R (version 3.1.1). As a result, 14 variables with VIFs > 5 were excluded (Chatterjee and Hadi 2006; Naranjo et al. 2017) and only eight variables were kept to establish the distribution model of P. ismaeli under the current conditions (Table 4).

MaxEnt model. In our study, the model was run using the MaxEnt algorithm (version 3.4.1 k; Guisan and Thuiller 2005; Jarvis et al. 2005; Phillips et al. 2006) with default settings. We analyzed the presence of the species in the different geographic regions, and the distribution along the Colombian Andes (Table 2) as proposed by Morrone (2014). We employed 10 replicates and the average of probability maps for habitat suitability (Hoveka et al. 2016). The training and test data points were 80 % and 20 %, respectively. The relative importance of each environmental predictor for the models of P. ismaeli was assessed using the percent contribution of the Jackknife test (Phillips et al. 2006), which is the best index for small sample sizes (Pearson et al. 2007).

Table 2 Selection of external and cranial measurements of P. ismaeli specimens collected in the central Andes eastern slope, Colombia. The measurements of the holotype and paratype of P. ismaeli were taken from Velazco (2005).

| Characteristics | This study CZUT-M 0058,0084 | Holotype MUSM 4946 | Paratypes FMNH 129134, 129136 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male |

| Weight | 32.00 | 39.00 | 35.00 | 40.00 | 38.00 |

| Total length | 88.32 | 80.40 | 84.00 | 82.00 | 87.00 |

| Hind foot length | 17.89 | 13.35 | 18.00 | 13.00 | 18.00 |

| Ear length | 22.75 | 21.03 | 10.00 | 21.00 | 22.00 |

| Forearm length | 52.65 | 53.25 | 52.00 | 53.00 | 54.00 |

| Tibia length | 21.35 | 19.75 | 21.68 | 19.52 | 21.68 |

| Greatest length of skull | 28.20 | 27.08 | 27.94 | 27.77 | 28.15 |

| Condyloincisive length | 27.30 | 26.59 | 27.10 | 26.57 | 27.47 |

| Condylocanine length | 26.92 | 26.07 | 26.22 | 26.07 | 26.88 |

| Postorbital breadth | 6.40 | 6.15 | 6.54 | 6.27 | 6.57 |

| Zygomatic breadth | 17.90 | 16.8 | 17.13 | 16.93 | 18.21 |

| Braincase breadth | 12.18 | 11.5 | 12.00 | 11.57 | 12.29 |

| Mastoid breadth | 13.69 | 12.5 | 13.99 | 13.63 | 14.72 |

| Maxillaty tooth row length | 11.78 | 11.05 | 11.35 | 11.43 | 11.66 |

| Breadth across maxilla | 20.71 | 20.56 | 12.63 | 12.65 | 23.81 |

| Palatal length | 15.94 | 14.9 | _ | _ | _ |

| Molariform teeth row length | 12.04 | 11.14 | _ | _ | _ |

| Width across first upper molars | 13.67 | 21.67 | _ | _ | _ |

| Width across second upper molars | 13.89 | 21.97 | _ | _ | _ |

| Dentary length | 24.60 | 28.00 | _ | _ | _ |

| Length of mandible toothrow | 15.70 | 21.56 | _ | _ | _ |

| Coranoid height | 7.07 | 14.96 | _ | _ | _ |

| Width at mandible condyles | 8.36 | 15.59 | _ | _ | _ |

| Breadth across molars | 15.42 | 22.83 | _ | _ | _ |

To determine the accuracy of the resulting models, we computed the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating characteristic Curve (ROC). AUC is the dominant tool to measure model performance, mainly due to its independence from threshold choices (Bosso et al. 2013; Fois et al. 2018; Yi et al. 2016). Higher AUC values (closer to 1) indicate better model performance (Fielding and Bell 1997; Phillips et al. 2006). The AUC graph was obtained by plotting true positive predictions (sensitivity) versus false positive predictions (1-specificity; Fielding and Bell 1997). In addition, the minimum difference between training and testing AUC data (AUCDiff) was also considered; a smaller difference indicates lesser overfitting in the model (Fois et al. 2018; Warren and Seifert 2011).

The logistic output of MaxEnt application is a map, indexing the environmental suitability of P. ismaeli with values ranging from 0 (unsuitable) to 1 (optimal). For further analysis, the MaxEnt results were imported into ArcGIS 10.4.1, and four classes of potential habitats were grouped as follows: unsuitable (≤ 0.10), low potential (0.11-0.30), moderate potential (0.31 - 0.70), and high potential (≥ 0.71; Yang et al. 2013; Choudhury et al. 2016; Qin et al. 2017).

Table 3 Environmental variables used for modeling the potential distribution of P. ismaeli. Issues related to collinearity were avoided by removing variables with variance inflation factor (VIF) values > 5. Variables highlighted in bold were selected through a multi-collinearity test and were used in modeling. All the variables were obain from the WorldClim.

| Variable | Code/Unit | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Annual Temperature | Bio1 (ºC) | 1.74 |

| Mean Diurnal Range (Mean of monthly (max temp - min temp) | Bio2 (ºC) | 2.68 |

| Isothermality (BIO2/BIO7) (* 100) | Bio3 | 1.10 |

| Temperature Seasonality (Standard deviation *100) | Bio4 (ºC) | 8.53 |

| Max. Temp. Warmest Month | Bio5 (ºC) | 12.90 |

| Min. Temp. Coldest Month | Bio6 (ºC) | 14.20 |

| Temperature Annual Range (BIO5-BIO6) | Bio7 (ºC) | 13.40 |

| Mean Temp. of the Wettest Quarter | Bio8 (ºC) | 9.20 |

| Mean Temp. of the Driest Quarter | Bio9 (ºC) | 3.14 |

| Mean Temp. of the Warmest Quarter | Bio10 (ºC) | 9.15 |

| Mean Temp. of the Coldest Quarter | Bio11 (ºC) | 9.23 |

| Annual Precipitation | Bio12 (mm) | 2.51 |

| Precipitation of the Wettest Month | Bio13 (mm) | 8.93 |

| Precipitation of the Driest Month | Bio14 (mm) | 3.39 |

| Precipitation Seasonality (Coefficient of Variation) | Bio15 | 1.85 |

| Precipitation of the Wettest Quarter | Bio16 (mm) | 12.86 |

| Precipitation of the Driest Quarter | Bio17 (mm) | 6.60 |

| Precipitation of the Warmest Quarter | Bio18 (mm) | 9.90 |

| Precipitation of the Coldest Quarter | Bio19 (mm) | 12.30 |

| Elevation | Elev (m) | 3.65 |

Results

The re-examination of the 10 specimens reported by Bejarano-Bonilla et al. (2007; CZUT-M 206 to 208, 0317) and Galindo-Espinosa et al. (2010); CZUT-M 57, 58, 83, 84, 144, 145), as P. aurarius or Ch. salvini, revealed the presence of P. ismaeli on the foothills of the eastern slope of the central Andes of Colombia, reported herein for the first time. These records expand the known distribution of P. ismaeli to approximately 328 km southeast of the nearest known locality in the Department of Huila, in the Parque Nacional Nevado del Huila, ‘’Cueva de los Guacharos’’ on the Acevedo trail (FMNH 58732, 58736, 58733 to 58735, 58737, 58738, Figure 1).

These new localities correspond to low montane forest and low montane wet forest, located in the Andean mountains, bordered by the dry tropical valleys of the Magdalena River. These landscapes are characterized by slopes with trees measuring approximately 12 m high and vegetation that includes plant species such as Pseudobomba septenatum, Calophyllum lucidum, Maclura tinctoria, Poulsenia armata, and Virola sebifera. These life zones are located primarily in areas subjected to intense agricultural and urban development, where the original forest has been cleared and replaced by plantations of coffee, fruit trees, vegetables, and other monocultures.

Figure 1 Map for potential current habitat suitability for Platyrrhinus ismaeli in Colombia from records in the various Colombian collections. Habitat suitability classes include: unsuitable, low potential, moderate potential, and high potential.

The diagnostic characters of the P. ismaeli specimens collected match the original description of the species (Velazco 2005; Diaz et al. 2016). The key features to recognize our specimens were: dorsal and ventral hairs with three bands; dense long hairs on the edge of the uropatagium; a medium forearm, less than 55 mm; upper central incisors with one or two cusps, but not cylindrical; presence of nasals; lingual cingulum not continuous from paracone to metacone (sulcus not continuous between paracone and metacone) of M1 (Figure 2); and cranial measurements (Table 2).

Potential habitat suitability of P. ismaeli over current conditions. Our models showed high levels of predictive performances with values of AUC (training, 0.974 ± 0.001; test, 0.957 ± 0.009) and AUCDiff (0.010 ± 0.007) indicating a good performance with low levels of errors and correctly identifying all the localities where the species has been reported (Figure 1). The results of the contribution of variables using the Jackknife test in distribution modeling of P. ismaeli are showed in Table 2. Environmental predictors that exhibited the highest mean contributions are annual precipitation (Bio12), annual mean temperature (Bio1), and elevation (Elev). At the same time, Bio1, Bio12, Bio9, Elev, and Bio5 provided high gains (> 2) to the model when used individually, indicating that each of these variables separately contribute the most useful information than the rest of variables. Considering the permutation importance, Bio1, Bio12, and Elev were the main environmental variables that have influenced the potential distribution of P. ismaeli (Table 2). The model predicts a continuous distribution range in the Colombian Andean region, spreading across the three cordilleras, i. e., western, central, and eastern, from the south in Nudo de los Pastos up to the Catatumbo subregion in the Department of Norte de Santander, including the Choco-Magdalena, Orinoquia, and North-Andean biogeographic provinces.

Table 4 Estimates of average contribution and permutation importance of the environmental variables used in the MaxEnt modeling for P. ismaeli.

| Variable | Percent contribution | Permutation importance |

|---|---|---|

| Bio1 | 13.6 | 29.5 |

| Bio2 | 0.6 | 2.3 |

| Bio3 | 3.6 | 7.4 |

| Bio9 | 1.5 | 3.6 |

| Bio12 | 33.6 | 8.0 |

| Bio14 | 1.5 | 1.4 |

| Bio15 | 0.3 | 1.1 |

| Elev | 12.5 | 5.3 |

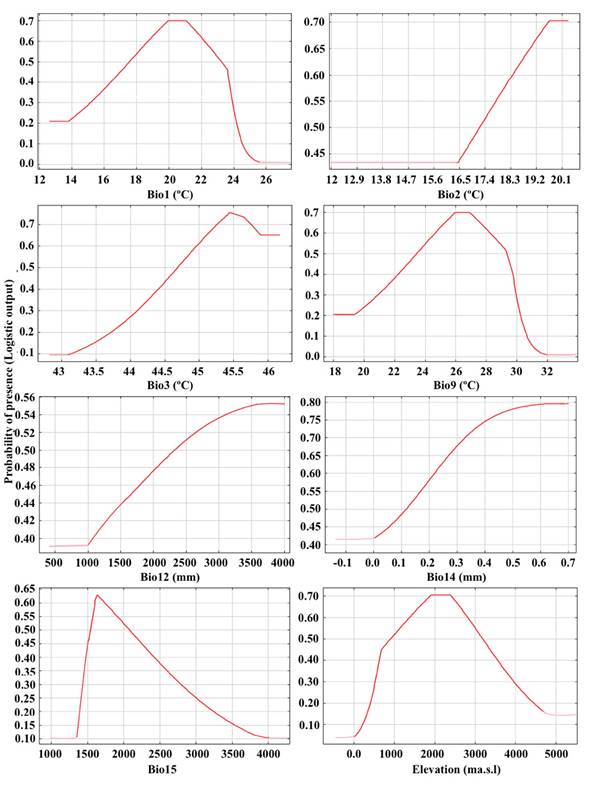

The response curves of eight variables related to P. ismaeli habitat suitability are shown in Figure 3. While considering temperature probabilities, the mean annual temperature range (Bio1) of P. ismaeli was 12.0 to 25.5 °C, whereas the mean diurnal temperature (Bio2) ranged from 16.5 to 20.15 °C. In addition, the range of isothermality (Bio3) varied from 43.1 to 46.3, whereas the mean temperature of the driest quarter (Bio9) varied from 28.0 to 32.0 °C. On the other hand, the range of annual precipitation (Bio12) was 1,000 to 4,000 mm per year while the suitable habitat occurs under a precipitation seasonality of 1,400 to 4,000, with a peak at 1,658 mm.

Figure 2 a) Dorsal, ventral, and occlusal views of the skull and jaw of a male of Platyrrhinus ismaeli (CZUT-M 317) captured in El Salitre trail, municipality of Cajamarca, Department of Tolima, Colombia, in July 2003. b) Occlusal views of the left first upper molar (M1) and second upper molar (M2). Lingual cingulum not continuous from paracone to metacone of first upper molar.

Furthermore, there is a positive relationship between habitat suitability for P. ismaeli and precipitation of the driest month. The elevation range suitable for P. ismaeli was 1,200 to 2,850 masl, with an optimal elevation at around 2,500 masl. Indeed, the conditions of highest suitability for P. ismaeli were an annual temperature of 21 °C, annual precipitation of 4,000 mm, and an elevation of 2,500 masl. By contrast, areas with an elevation above 3,000 masl or below 1,200 masl, and with an annual temperature above 30 °C were the least suitable for P. ismaeli.

The potential distribution map of P. ismaeli in Colombia is shown in Figure 3. Out of the total area of 1,141,748 km2, some 5,103 km2 were potentially suitable for P. ismaeli. This area was divided into 1,793 km2 with a low potential, 1,758 km2 with a moderate potential, and only 1,551 km2 with a high probability of suitable ecological conditions. The majority of suitable habitats (≥ 0.71) were located in areas located in the mid-north of Colombia.

Figure 3 Response curves of eight environmental predictors used in the ecological niche model for P. ismaeli. For abbreviations, see Table 3.

Discussion

Our results update and show a wider distribution range of P. ismaeli in Colombia (Table 1). This work is the first record of this species in the eastern slope of central range of Colombia. The existing records of the species correspond to the life zones low montane forest, low montane wet forest and premontane very humid forest. These life zones in Colombia are subjected to an increasing destruction and degradation of habitats, primarily due to agriculture, forestry, illegal crops, and mining, which altogether have resulted in a decline of more than 30 % of the populations of P. ismaeli (Ramírez-Chaves and Suárez-Castro 2014; Solari 2016); thus, the species is currently listed as Near Threatened (NT).

The records reported here also represent an extension of the ecological range of P. ismaeli. The life zone represented by low montane very humid forest has environmental and climatic characteristics that differ from others previously reported for the species, with precipitation between 2,000 to 4, 000 mm and temperature between 12 to 18 °C. Natural forests in this area were characterized by broad extensions, several arboreal strata, many epiphytes, and fertile soils; however, today most of the forest has been transformed into pastures for agriculture and cattle raising, which causes overgrazing and excessive clearing (Guzmán-González 1996).

Our results show that under the current climatic conditions, the areas with the best environmental suitability for P. ismaeli are located in the north-center regions of Colombia. This finding is consistent with the records in Colombian collections and the known distribution reported in the literature (Solari et al. 2013), and suggests that the current distribution represents the optimum climatic conditions for the species, in sites of high altitude (2,500 masl) and near steep slopes, with riparian vegetation ecosystems.

The results of the model show that all the current and predicted sites fulfill suitable conditions for P. ismaeli, i. e., high elevation (1,200 to 2,850 masl), low temperature (12.0 to 25.5 °C), and annual precipitation range of 1,000 to 4,000 mm. Consequently, warm sites with elevation < 1,200 masl are less suitable for the species. These results are in line with those from Solari et al. (2013), which report that P. ismaeli mainly lives in wet habitats with a narrow elevation range from 1,230 to 2,950 masl.

However, some studies also report the presence of P. ismaeli in premontane forests in mountain ranges (Asprilla-Aguilar et al. 2016). In fact, this species prefers secondary forests with abundant vegetation cover, rather than pastures and monocultures or moderately fragmented areas (Tirira 2011), to the extent that it is considered endemic to Yungas in Perú, the ecoregion with the largest number of endemic species (Pacheco et al. 2009). The distribution of P. ismaeli covers the driest forests of the western slopes of the Andes in northern Perú (Rengifo et al. 2011).

Our analysis revealed that the highest probability of occurrence of P. ismaeli is recorded in the center of the North Andean Province in the Departments of Antioquia, Caldas, Cundinamarca, Huila, Tolima, Quindío, and Valle del Cauca. The model also predicts a high probability of occurrence in the Choco--Magdalena region and the east of the Orinoquia region. Altogether, this suggests that the distribution of P. ismaeli is governed by the ecological association between the Chocó biogeographic region and the valleys of the Magdalena and Cauca rivers, an exchange zone of the biological elements of these areas with those of the cis-Andean and Magdalena valleys, moving through the foothills of the Orinoquia, the Burbua depression, and the Catatumbo basin. This pattern has been documented for different groups of animals, including bats (Hernández-Camacho et al. 1992; Mantilla-Meluk et al. 2009; García- Herrera et al. 2018).

In addition, MaxEnt outputs under the current conditions indicate that the distribution range of P. ismaeli is influenced primarily by annual temperature, annual precipitation, and elevation. This is consistent with factors affecting the suitable habitats of several groups of vertebrates such as amphibians, non-volant mammals, bats, and birds (Moura et al. 2016; Molinari et al. 2017), where climatic factors and elevation resulted core drivers of the distribution of vertebrate species (Ferro Muñoz et al. 2018).

This study provides ecological information about the habitats occupied by this species, as well as a detailed geographic distribution in the Andean region. This information can be used to support the development of scientifically sound conservation plans, as well as detailed and reliable distribution maps for Colombia, thus allowing the identification of areas that are suitable for the conservation of this species in the country. However, further studies are required addressing the distribution of species in the Central range of Colombia, a region that maintains some high-biodiversity areas in spite of the recent anthropogenic impacts.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)