Introduction

Like platypus and echidnas (Subclass Prototheria) and some fossil placentals, marsupial mammals (Infraclass Marsupialia sensuBurgin et al. 2018) are characterized by the presence of epipubic bones (Reilly and White 2003), which are not found in current members of Infraclass Placentalia (sensuBurgin et al. 2018). These are paired bony structures that articulates with the pubis and extend forward into the ventral abdominal wall (Marshall 1979). In most species they are long bones, depressed and apically sharp, and have two faces, two edges and two ends (Ferrusquia-Villafranca 1964). Therefore, the pelvic girdle of the marsupials is composed of the bones ilium, ischium, pubis, and epipubics (Figura 1).

Function of epipubic bones of marsupials presumably reflects emphasis on different but non-mutually exclusive functions. It has been proposed, on one hand, that they serve as a support mechanism for the marsupium or pouch and the offspring that are found inside by helping the abdominal musculature in the support of the abdomen (Elftman 1929; White 1989). On the other, it has been stated that epipubic bones act as a lever to facilitate the rigidity of the body through the limbs during walking and jogging (Reilly and White 2003); both females and males have epipubic bones, but the latter lack a pouch in almost all species of marsupials. If these bony structures are linked to the presence of a marsupium to provide support, then males would be expected to show little developed epipubic bones. Accordingly, White (1989) reported that epipubic bones of species with marsupium, as Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) are longer, in general, in females than in males for a given mass (g); unfortunately, he did not report the dimensions of the epipubic bones he studied yet the size values of those bones he examined cannot be compared.

On the other hand, research data have shown that males adult Virginia Opossum are larger than females, condition that becomes apparent at the beginning of sexual maturity (Gardner 1982). Sexual dimorphism, therefore, may be a secondary consequence of reproductive activity; smaller size and lighter weight of females may be the result of spending more energy in rearing youngs (Gardner 1982). ; Tague 2003). Similarly, differences between sexes in cranial and mandibular dimensions were found in the Virginia Opossum from Georgia, USA (Patterson and Mead 2008). In addition, canine teeth of males, and pelvic and non-pelvic dimensions are larger as well (Tague 2003; Patterson and Mead 2009); unfortunately, none of these reports estimated epipubic bone size. In contrast, Ventura et al. (2002) informed that sexual dimorphism in size may not be a general pattern in Didelphis after examining South American opossums (D. marsupialis, D. pernigra, and D. imperfecta). Therefore, the relationship between length of this pelvic girdle structure and length of an individual remains unexplored.

Unfortunately, there are no data available on linear dimensions of both epipubic bones and specimens examined to evaluate these issues and to better understand the relationships between sexual dimorphism and epipubic bone size. However, Mexican species of opossum (Didelphidae) are a good data source to contribute further information about this topic, particularly D. virginiana. This is the most common opossum species in México, with a wide geographical distribution and with numerous specimens represented in biological collections (Gardner 1982; Astúa 2015).

The objective of this work is, then, to describe and measure the size of the epipubic bones for females and males of the Virginia Opossum from México and assess their size relative to a measurement of body length assessed as skull length. These results will also allow to estimate what percentage of the length of an individual, as revealed by skull length, represents the length of the epipubic bones and compare between sexes.

Materials and Methods

A total of 102 specimens of the Mexican Virginia Opossum (D. virginiana) deposited in the Mammal National Collection (CNMA) of Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (IBUNAM), were examined but a subsample of 45 (28 males and 17 females) adult specimens were included in the morphometric analysis due to their good preservation condition (Appendix 1). Adulthood was assessed according to the sequence of molar eruption and replacement of the last deciduous premolar (Gardner 1982), as well as fusion of the ilium, ischium, and pubis at the acetabulum (Tague 2003).

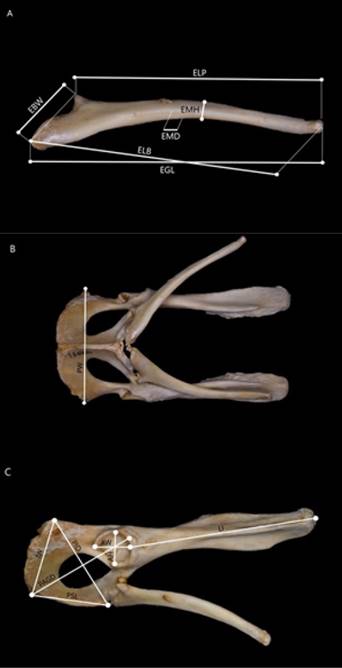

For each specimen, 16 pelvic and non-pelvic variables were taken with a digital vernier (Mitutoyo Co.) at a precision level of 0.01 mm. Pelvic variables recorded were six measurements of the right epipubic bone (Figure 1a): Epipubic greatest length (EGL), Epipubic length from the base (ELB), Epipubic length from the process (ELP), Epipubic base width (EBW), Epipubic medium height (EMH), and Epipubic medium depth (EMD); six measurements of the pelvic girdle (Figure 1b, 1c): Pelvis width (PW), Ischium width (IW), Pubic symphysis length (PSL), Pubis to ischium distance (PID), Pubis to acetabulum greatest distance (PAGD), and length of the Ilium, from it joins the acetabulum to its anterior most end (LI); and two of the acetabulum (Figure 1c): Acetabular width (AW), Acetabular height (AH). Non-pelvic variables were two conventional cranial measurements: Skull greatest length (SGL), and Zygomatic width (ZW), recorded according to Ryan (2011). Statistical significance of Student’s t-test was set at P ≤ 0.05; when data were not normally distributed a non-parametric Wilcoxon test was utilized. In addition, we also examined specimens of other Mexican opossum species for comparative purposes.

To illustrate how the skull, epipubic bones, the rest of the pelvic girdle and the vertebrae of the sinsacral look like, we prepared digital files and uploaded them into the IREKANI collection of images of CNMA at IBUNAM available at http://unibio.unam.mx/irekani/.

Results and Discussion

Our results produced 16 digital files (numbers: 12606-12621) containing photographs and curatorial data of juvenile, adult, female, and male specimens of the Mexican Virginia Opossum (D. virginiana), and the ring-tailed cat (Bassariscus astutus) just for visual comparative purposes with a placental mammal; for the first species resulted 14 files while just two for the latter species. One of the 14 files include the right epipubic bone of each species of Mexican opossums (Didelphidae). These are the first published data set that shows images of epipubic bones of Mexican species of opossums.

The epipubic bone of the Mexican Virginia Opossum is a long, thin bone with a shape almost right to a slightly curved and a thickening with a notch at its base; the shape of this bone in young individuals is practically the same as in adults. It is located in the ventral part of the pelvic girdle, where it articulates with the right pelvic bone and extends towards the front and a little downwards almost parallel to the ilium bone of the pelvic girdle, coinciding with that reported by Tague (2003) who additionally points out that epipubics extend from the superior border of the pubis to approximately the plane of the sacroiliac joint. Similarly, we found that the epipubic bone of other Mexican opossum species of the genera Philander, Metachirus, Caluromys, Chironectes, Marmosa, and Tlacuatzin is also elongated, thin and little curved, what makes it similar in shape to that of Mexican Virginia Opossum specimens. In addition, Flores (2009) reported that the distal portion of the epipubic bones of Caluromys, Chironectes, and Marmosa is clearly curved. Ferrusquía-Villafranca (1964) also mentioned that Chironectes minimus has an epipubic with an almost straight internal edge and the outer tubercle of the proximal end not very prominent, like Caluromys derbianus.

Figure 1 Pelvic measurements recorded in adult Mexican opossums (Didelphimorphia) from Mammal National Collection (CNMA) of Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). A, lateral right view of the right epipubic bone. B, ventral view of the pelvic girdle. C, lateral right view of the pelvic girdle. Measurements names are indicated in text.

The two measurements of acetabulum size and those of length and width of skull of Mexican D. virgininana showed that males are larger than females. That is, the average values of the Acetabular width (AW), Acetabular height (AH), Skull greatest length (SGL), and Zygomatic width (ZW) had a significantly higher mean value in males than in females (Table 1); larger acetabulum may articulate with a larger femur head of a larger femur. Other research on the pelvic sexual dimorphism in the Virginia Opossum (Tague 2003) revealed that in general males have pelvis larger than females, since 14 of 16 absolute dimensions of the pelvis were significantly higher in males. Unfortunately, no data on acetabulum dimensions were provided therein. Provided that these variables may be estimators of size, our data then agree with previous reports for North American populations of this species (Gardner 1982; White 1989), that adult males of the Virginia Opossum are larger than females.

However, we did not find significant differences between sexes regarding the other six measurements we recorded for other pubic bones. This is, lengths, widths and distances involving ilium, ischium, and pubis (PW, IW, PSL, PID, PAGD, and LI; Table 1). This result is similar to that reported by Elftman (1929) and Ferrusquía-Villafranca (1964) who mention that pelvis of females and males are not different from edach other in D. virginiana, P. opossum and C. minimus.

Interestingly, we also found that although males display longer acetabulum, females have longer epipubic bones (mean EGL = 4.4 cm) than males (Table 1). This evidence of sexual dimporphism is supported by the variables Epipubic greatest length (EGL), Epipubic length from the base (ELB), and Epipubic length from the process (ELP) of females since are significantly larger than those that were recorded for males (Table 1). Our findings coincide with the results of White (1989), who states that females generally have longer epipubic bones than males for a given mass (not length). Our data therefore using a linear variable, length (mm), confirm what White (1989) reported using a variable of mass (g) regarding individual size between sexes. Ferrusquía-Villafranca (1964) also noted that females display relatively larger, more robust and curved epipubics than males.

In addition, our data showed then that the average greatest length of the epipubic bones (EGL) of adult males represents solely 29.13 % of the size of the average total length of their skull (SGL), while in females this proportion reaches 47.78 %; the epipubic bone of females is also relatively larger than that for males. For instance, in our sample examined (Table 1) SGL and EGL of an adult male (CNMA 45122) are, respectively: 110.70 and 37.44 mm, whereas for a female (CNMA 3523) these values are 97.36 and 47.22 mm (Figure 2). In contrast, the other three variables we recorded related with epipubic bones (Epipubic base width, EBW, Epipubic medium height, EMH, and Epipubic medium depth, EMD) did not show significant differences between sexes (Table 1).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and range) and comparison of means of pelvic and non-pelvic variables (mm) between sexes of adult Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana). * = significant difference at 0.05 level.

| Variable | Males(n = 28) | Females(n = 17) | Student´s t - test | Wilcoxon -test |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epipubic greatest length | 38.45 ± 4.43(31.00- 44.27) | 43.97 ± 7.48(27.78 -54.33) | 0.003* | 0.001* |

| Epipubic length from the base | 31.98 ± 4.71(22.80 - 39.45) | 37.62 ± 6.92(23.24 -48.61) | 0.009* | 0.008* |

| Epipubic length from the process | 33.42 ± 4.09(26.40 - 40.09) | 39.51 ± 6.87(24.78 -50.07) | 0.004* | 0.002* |

| Epipubic base width | 11.60 ± 1.32(8.03 - 13.35) | 12.47 ± 1.86(8.16 - 14.88) | 0.117 | 0.105 |

| Epipubic medium height | 3.10 ± 0.50(2.21 - 3.77) | 3.28 ± 0.96(1.43 - 5.29) | 0.497 | 0.421 |

| Epipubic medium depth | 1.79 ± 0.36(1.13 - 2.44) | 1.98 ± 0.64(0.56 - 2.82) | 0.261 | 0.164 |

| Pelvis width | 40.94 ± 5.28(34.25 -48.12) | 37.20 ± 6.35(24.27 - 43.8) | 0.099 | 0.143 |

| Ischium width | 28.41 ± 5.90(20.04 - 35.39) | 28.48 ± 3.87(19.53 - 33.26) | 0.555 | 0.69 |

| Pubic symphysis length | 21.11 ± 3.16(12.74 - 25.06) | 20.42 ± 3.5(12.57 - 24.63) | 0.961 | 0.824 |

| Pubis to ischium distance | 32.04 ± 3.74(23.92 - 37.84) | 30.16 ± 3.65(21.37 - 34.9) | 0.109 | 0.076 |

| Pubis to acetabulum greatest distance | 35.76 ± 3.79(27.12 - 42.56) | 34.49 ± 3.95(24.88 - 38.79) | 0.297 | 0.361 |

| Length of the Ilium | 48.50 ± 4.09(37.21 - 55.79) | 48.42 ± 6.86(32.96 - 56.45) | 0.940 | 0.497 |

| Acetabular width | 9.87 ± 1.18(7.37 - 12.39) | 8.77 ± 1.09(6.70 - 11.05) | 0.003* | 0.004* |

| Acetabular height | 9.49 ± 1.12(7.57 - 11.45) | 8.18 ± 1(6.17 - 10.07) | 0.000* | 0.001* |

| Skull greatest length | 108.38 ± 11.81(124.75 - 80.56) | 99.08 ± 11.47(72.23 - 115.76) | 0.014* | 0.017* |

| Zygomatic width | 56.56 ± 7.16(40.18 - 70.68) | 50.35 ± 6.31(36.44 - 58.98) | 0.005* | 0.007* |

Length of the epipubic bone for the two species of the genus Didelphis examined here, (D. virginiana and D. marsupialis) turned out to be the largest values in the sample for the opossum species of México. Accordingly, the smallest recorded epipubic bones corresponded to the smallest species of Mexican marsupials, the mouse opossums (Marmosa mexicana and Tlacuatzin canescens); females of these small marsupials do not have a marsupium; however, they display well developed epipubic bones. If proportionally small epipubic bones of mouse opossums is an evolutionary result of lack of marsupium remains to be tested. However, Flores (2009) reported larger development of epipubic bones in females of pouchless taxa.

Figure 2 Skull length relative to epipubic bone length in adult Virginia Opossum (Didelphis virginiana) from México. Above: male (CNMA 45122); below: female (CNMA 3523). Body size of the first is larger but the latter has a larger epipubic bone.

Except D virginiana, the small sample size available for other species of Mexican opossums prevents comparisons between species. However, a tendency can be noted where the length of the epipubic bones of D. virginiana, D. marsupialis, Philander opossum, Chironectes minimus and Metachirus nudicaudatus represent almost half the size of the skull. Similarly, Flores (2009) found that the proximal size of the epipubic bones is long in Didelphis, Caluromys, Philander and Marmosa (except M. rubra). In contrast, length of the epipubic bones of Caluromys derbianus, Marmosa mexicana, and T. canescens are around a third of skull length.

In summary, epipubic bones is an important distinctive characteristic of marsupials, it has been little studied and there are still few available data on its morphology. However, our study makes available by first time summarized data based on length and images on epipubic bones of Mexican species of opossums, particularly the Mexican Virginia Opossum.

Our data confirm that males of Mexican opossums Didelphis virginiana are larger than females, and that epipubic bones are significantly larger in the latter; epipubic bone length of a female is almost half size her skull length. Therefore, epipubic bones are an important landmark of sexual dimorphism in D. virginiana, and our data may be useful to learn more about epipubic bones of other marsupial mammals. Undoubtedly, further research is needed to better understand the role of epipubic bones in the structure and function of pelvic girdle of marsupials.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)