Introduction

The genus Leptospira encompasses a set of thin bacteria with hook-shaped tips that inhabit lentic habitats worldwide, particularly wetlands (Levett 2015). Previously, the existence of two species was recorded: a saprophytic species thriving in aquatic environments (L. biflexa) and a pathogenic one causing a zoonosis called leptospirosis (L. interrogans;Levett 2015). Today, 35 species are acknowledged, classified into three groups based on their ability to infect vertebrate hosts: non-pathogenic (e. g., L. biflexa, l. idonoii, and L. meyeri), facultative pathogenic (e. g., L. broomii, L. fainei, and L. wolffii) and pathogenic (e. g., L. alexanderi, L. borgpetersenii, L. interrogans, and L. kirschneri; Bourhy et al. 2014; Thibeaux et al. 2018).

Ten pathogenic species are currently known, which have been reported in more than 160 species of wild and domestic mammals around the world (Ballados-González et al. 2018). In particular, rodents play a role as reservoirs; many murine species exhibit chronic infections and continually release bacteria in urine, a phenomenon called leptospiruria. Members of the family Muridae serve as the main reservoirs of Leptospira sp., and are deemed responsible for spreading the infection to livestock, pets, and humans (da Silva et al. 2010; Colombo et al. 2018).

In México, few studies have been conducted to detect Leptospira sp. in rodents, mostly in the states of Tamaulipas, Campeche, and Yucatán (Méndez et al. 2013; Espinosa-Martínez et al. 2015; Torres-Castro et al. 2016; Panti-May et al. 2017; Torres-Castro et al. 2018). These studies provide molecular evidence of the presence of L. interrogans and L. kirschneri in various species of rodents of the families Cricetidae, Heteromyidae, and Muridae. However, there are other states of México where human and bovine leptospirosis is a major public health issue. Specifically, the state of Veracruz records an incidence of human leptospirosis of five cases per 100,000 inhabitants, and seroprevalence in livestock ranging between 60 % and 80 % (Moles-Cervantes et al. 2002; Álvarez et al. 2005; Sánchez-Montes et al. 2015; Zárate-Martínez et al. 2015). However, there is no evidence on the Leptospira species maintained in rodent populations in the region. The aim of the present work was to determine the presence and diversity of Leptospira sp. in synanthropic rodents in the Nautla region, Veracruz, México.

Materials and Methods

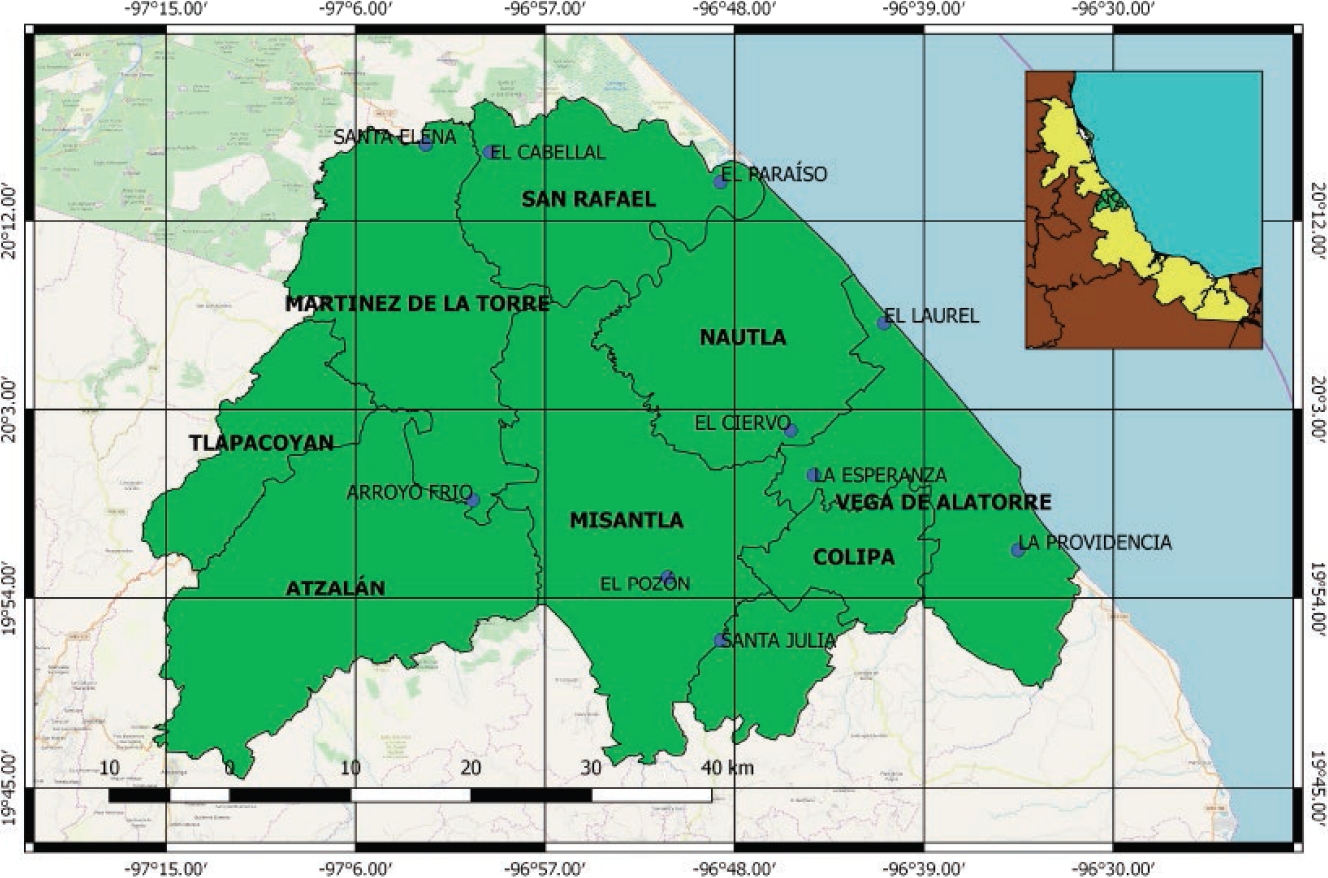

This study was conducted in well-defined and delimited areas that have facilities, machinery, and equipment to carry out livestock activities, named Livestock Production Units (LPU), in the municipalities of San Rafael, Nautla, Martínez de la Torre, Vega de Alatorre, and Misantla, in the Nautla region, Veracruz (Figure 1). This region is located in the center-northern portion of the State of Veracruz. It is bordered by the Totonac region to the north, the Capital and Mountain regions to the south, the Gulf of México to the east, and the state of Puebla to the west. This region covers an area of 3,329 km2, with 86.1 % dedicated to farming activities; in turn, 43.2 % is covered by pastures for cattle raising.

Figure 1 Map of the location of the Production Units sampled in the Nautla region, Veracruz, Mexico. The municipalities that make up the Nautla region are highlighted in green. The localities sampled are marked with blue circles.

Rodents were sampled from November 2016 to May 2017 on Production Units across the Nautla region, Veracruz. In each Production Unit, Sherman® traps were placed (8×9×23 cm), using an oat-vanilla mixture as bait attractant. Forty traps were placed per Production Unit, strategically distributed in areas with high probability of occurrence of rodents such as warehouses, farmyards, or inside households. Traps were placed in the afternoon and reviewed the next morning (before 7 am) during two trapping nights in each locality. The rodents captured were removed from traps, identified, and processed for kidney sample collection following biosafety standards, under collection license FAUT-0250 granted by the Secretariat of Environment and Natural Resources (Semarnat). Animals were euthanized according to the protocol established by NOM-033-SAG/ZOO-2014 using ketamine (Wildlife Pharmaceutics México SA de CV 04930, México) as anesthetic agent, followed by cervical dislocation. Each rodent was placed in supine position and the absence of reflexes (corneal and podal) was confirmed before dissection to remove the kidneys. Kidney samples were placed in containers with 70 % alcohol and kept at 4 °C until processing.

DNA extraction was carried out in each sample separately, using 500 µl of a 10 % solution of the resin Chelex 100 added with 20 µl of proteinase K; then samples were incubated at 56 °C for two hours (Ballados-González et al. 2018). Afterward, samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes; the supernatant was transferred to new tubes and stored at -20 °C.

Once the sample was obtained, a 474-bp segment of the outer membrane protein LipL32, present in the genome of the pathogenic Leptospira species, was amplified using the oligonucleotides (ATCTCCGTTGCACTCTTTGC) and LipL32 reverse (GTCCGCCTACACACCCTTTAC; Vital-Brazil et al. 2010). The reaction mixture consisted of 12.5 μl of a 2X solution of GoTaq® Green Master Mix (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), 1 μl of each oligonucleotide (2µM each), 6.5 μL of DNase-free water, and 4 µl of DNA (200-300 ng) to make a final volume of 25 μL (Espinosa-Martínez et al. 2015; Ballados-González et al. 2018). Amplicons were visualized on agarose gels using 2 % TAE buffer at 85 V for 45 min.

Positive PCR products were sent to the Biology Institute at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for sequencing. The resulting sequences were compared with those deposited in GenBank to determine the similarity between them using the BLAST tool.

Global alignments were carried out between the sequences produced in this study and some representative pathogenic leptospires deposited in GenBank, with the algorithm Clustal W using the software MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al. 2013). The Tamura’s three-parameter model of nucleotide substitution (T92) was selected based on the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) score (2,497,948). In addition, a phylogenetic reconstruction was conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) approach; the support of the topology was validated with 10,000 bootstrap replicates, also in MEGA 6.0.

Results

A total of 28 specimens of Mus musculus were collected. None of the collected animals showed signs of disease at the time of collection, nor gross evidence of renal impairment. Leptospira DNA was detected in 17 of the 28 samples analyzed (62.9 %; CI95% 42.3 to 80.59). Positive samples were obtained from animals collected in the localities of La Providencia, La Esperanza, Santa Julia, El Pozón, El Laurel, El Cabellal, and Tres Marías (Table 1).

Table 1 Location of the Production Units sampled in the Nautla region, Veracruz, Mexico. RC = Rodents collected; PR = Positive rodents; % = Prevalence

| Locality | Municipality | Latitude | Longitude | RC | PR | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La Providencia | Vega de Alatorre | 19° 56’ 0.47” | -96° 32’ 59.02” | 2 | 1 | 50 |

| El Ciervo | Vega de Alatorre | 20° 02’ 00.31” | -96° 45’ 18.97” | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| La Esperanza | Vega de Alatorre | 19° 59’ 53.26” | -96° 44’ 13.48” | 2 | 1 | 50 |

| Santa Julia | Misantla | 19° 52’ 00.26” | -96° 48’ 38.30” | 5 | 4 | 80 |

| El Pozón | Misantla | 19° 55’ 03.14” | -96° 51’ 09.71” | 5 | 2 | 40 |

| El Laurel | Vega de Alatorre | 20° 07’ 04.62” | -96° 40’ 53.18” | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| El Paraíso | San Rafael | 20° 13’ 51.00” | -96° 48’ 39.09” | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| El Cabellal | San Rafael | 20° 15’ 15.24” | -96° 59’ 36.23” | 4 | 4 | 100 |

| Santa Elena | Martínez de la Torre | 20º 13’ 55.49” | -97° 01’ 23.89” | 4 | 3 | 75 |

| Arroyo Frio | Martínez de la Torre | 19° 58’ 43.10” | -97° 00’ 25.23” | 1 | 1 | 100 |

| Total | 28 | 17 | 60.7 |

The localities with the highest number of positive mice were Santa Julia (municipality of Misantla), and El Cabellal (municipality of San Rafael), with four positive specimens each (Table 1). Of the 17 positive PCR products, 12 sequences of 460 to 470 base pairs were recovered. The recovered sequences exhibited 99 % identity between them (457/460 bp), and 99 % identity (458/460 bp) with sequences of L. borgpetersenii deposited in GenBank. In addition, the phylogenetic analysis encompassed the sequences observed in this study along with the reference sequence of L. borgpetersenii in a monophyletic group with a support value of 100 (Figure 2). The sequences generated in this study were deposited in GenBank with access numbers MK568973-MK568984.

Discussion

This work is the first approximation to the study of Leptospira in rodents in the northern part of the state of Veracruz. Besides, it represents the first molecular confirmation of the presence of L. borgspetersenii in rodents, particularly in Mus musculus, in México (Espinosa-Martínez et al. 2015; Torres-Castro et al. 2016, 2018; Panti-May et al. 2017). The reference serovar of L. borgspetersenii isolated from M. musculus is Ballum, which was detected in the past century in Europe (Yager et al. 1953). Since then, multiple serological and molecular studies have shown that this serovar is widely distributed across M. musculus populations worldwide (da Silva et al. 2010; Matsui et al. 2015; Colombo et al. 2018). In México, studies conducted in the state of Durango have reported titers of antibodies to the L. borgspetersenii Ballum serovar in domestic animals such as pigs and donkeys (Alvarado-Esquivel et al. 2018; Cruz-Romero et al. 2018). Thus, it is reasonable to assume that domestic animals can be exposed to bacteria through rodents and food or water sources contaminated with rodent urine in farmyards or livestock handling and processing areas.

The presence of two additional species of pathogenic leptospires (L. weilli and L. noguchii) has been confirmed in the state of Veracruz, both in kidney tissue samples of the hematophagous bat Desmodus rotundus and the frugivorous bat Artibeus jamaicensis (Ballados-González et al. 2018). Therefore, this study increases the inventory of pathogenic leptospires of Veracruz to three species. These findings in rodents suggest the existence of multiple transmission cycles in both wild and anthropic environments, which should be evaluated carefully.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)