Introduction

Of the Families of terrestrial mammals, shrews (order Eulipotyphla, family Soricidae) are a highly diverse group in Mexico, represented by four genera and at least 36 species: Cryptotis (15 spp.), Megasorex (1 sp.), Notiosorex (4 spp.), and Sorex (16 spp.; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014; Guevara et al. 2014a). Recently, this group has undergone several taxonomic and nomenclatural changes (Douady et al. 2002; Carraway 2007; Woodman et al. 2012; Guevara et al. 2014a; Matson and Ordóñez-Garza 2017).

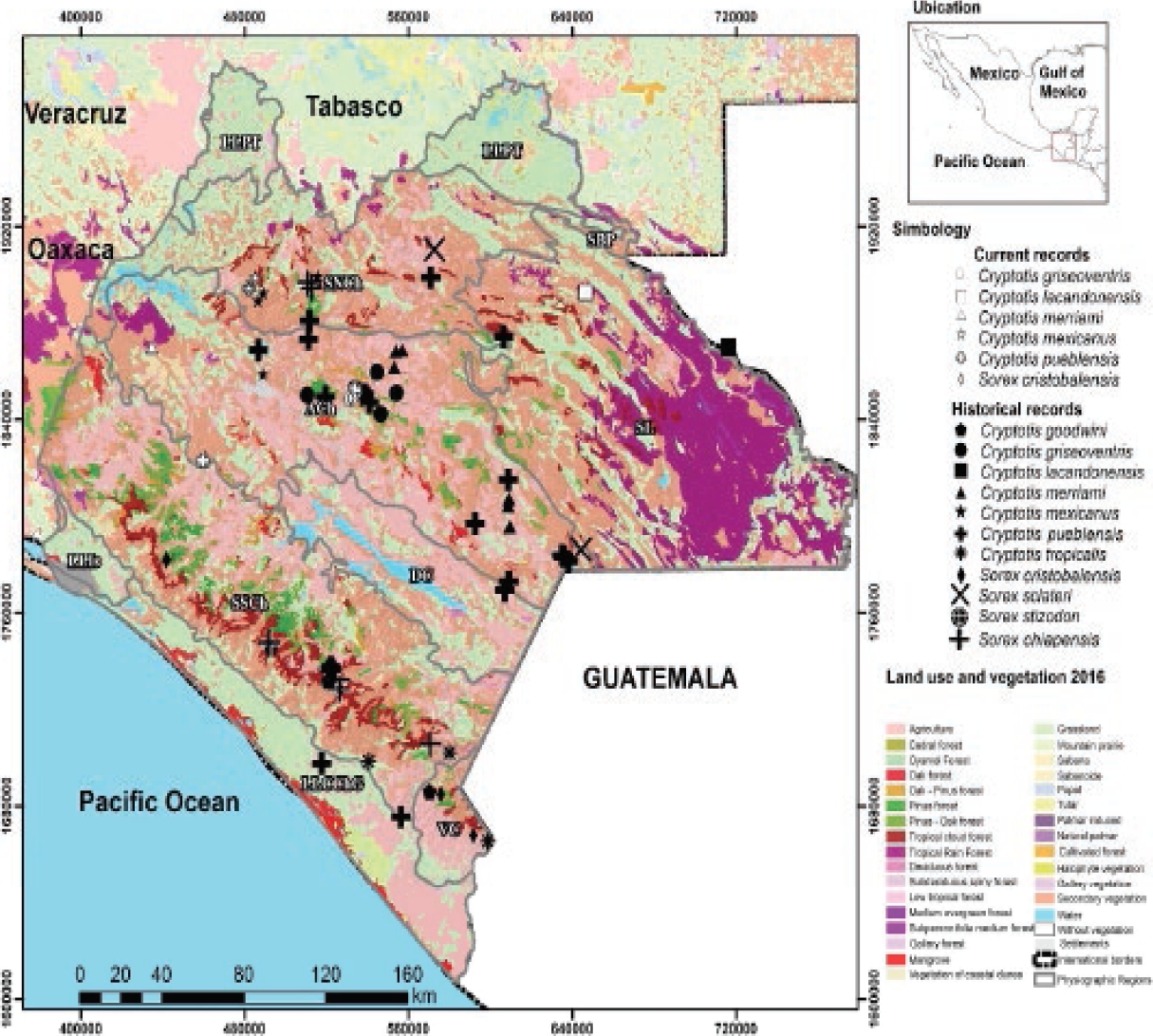

In Chiapas, shrews are represented by two genera (Cryptotis and Sorex) and 11 species: Cryptotis goodwini, C. griseoventris, C. lacandonensis, C. merriami, C. mexicanus, C. pueblensis, C. tropicalis, Sorex cristobalensis, S. sclateri, S. stizodon, and S. chiapensis. These species are distributed in six of the physiographic regions of Chiapas: Los Altos of Chiapas, Central Depression of Chiapas, Coastal Plain of Chiapas and Guatemala, Sierras of Northern Chiapas, the Lacandon Forest Ravines, Soconusco, and the Eastern portion of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, from sea level up to 3,650 masl (Lorenzo et al. 2017). Specifically, shrews inhabit various habitats, including forests (mountain cloud, pine, oak, cedar, fir, and the associations thereof), mountain grasslands, tropical forests (high, medium, and low, evergreen, subdeciduous, deciduous), grasslands and secondary vegetation (Lorenzo et al. 2017).

Of the 11 species of shrews distributed in Chiapas, five (45.4 %) are endemic to the state (Sorex stizodon, S. sclateri, S. cristobalensis, Cryptotis lacandonensis, and C. griseoventris), indicating that the State is home to 30.5% of the diversity of shrews known in Mexico (Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014; Guevara et al. 2014a; Lorenzo et al. 2017; Burgin et al. 2018).

Five species of shrews in Chiapas are listed under a protection category in the Mexican Official Standard NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010 (SEMARNAT 2010): C. tropicalis (as C. parva tropicalis) and Sorex cristobalensis (as S. saussurei cristobalensis), subject to special protection (Pr); and S. sclateri, S. stizodon, S. chiapensis (as S. veraepacis chiapensis), as threatened (A). The red list of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN 2018) includes C. tropicalis (as C. parva tropicalis) as Data Deficient (DD), C. griseoventris as Endangered (EN), S. sclateri and S. stizodon as Critically Endangered (CR), and S. chiapensis as Least Concern (LC), being a subspecies of S. veraepacis. Cryptotis lacandonensis has not yet been evaluated.

Despite the high diversity of shrews in Chiapas, the number of localities and specimens deposited in biological collections are relatively small (Guevara et al. 2015). Besides, the information on ecological aspects is practically null. These facts prevent proper evaluation of the taxonomic and conservation status of the shrew species (Guevara et al. 2015; Burgin et al. 2018). For the above, this paper describes the efforts made by the authors along 16 years in search of the species of shrews of Chiapas. The results include information about the distribution and ecology of species, as well as the scenario of future research for the conservation of shrews and their habitat in Chiapas.

Materials and Methods

We collected information from the sampling of shrews of Chiapas at 13 different sites during 19 field trips from 2002 to 2018, each of different duration in days (Table 1). The sampling sites were located in mountain cloud forests, pine-oak forest in moist soil covered with leaf litter, medium and high tropical forest, fallow lands with patches of cloud forest, and coffee plantations. In each trip, we placed between 100 and 200 one-liter pitfall traps with no diversion fences.

Table 1 Records of species of shrews of Chiapas from 2002 to 2018 in different sampling dates and collection data using pitfall traps. ECO-SC-M = Mammal Collection of ECOSUR. CNMA = National Collection of Mammals.

| Sampling Date (month/day/year) | Species | Catalog Collection No. (in order of appearance) | Locality | Latitude | Longitude | Vegetation | Height (m) | No. of Traps | No. of Nights | No. of Trap-Nights |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 05/22/2002 | Cryptotis griseoventris | ECO-SC-M 1429 | 1 | 16.7491° | -92.6838° | Cloud Forest | 2,376 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| 11/7-9/2003 | Sorex cristobalensis | CNMA 42919 |

2 | 16.7580° | -92.6813° | Cloud Forest | 2,367 | 200 | 2 | 400 |

| 08/4-6/2005 | Cryptotis merriami | ECO-SC-M 4429 | 3 | 16.4883° | -93.3800° | Coffee plantation | 1,453 | 100 | 3 | 300 |

| 01/14-16/2006 | Cryptotis pueblensis | ECO-SC-M 1807 | 1 | 16.7538° | -92.6819° | Cloud Forest | 2,400 | 100 | 2 | 200 |

| 04/22-24/2007 | 2 | Cloud Forest | 2,400 | 100 | 2 | 200 | ||||

| 09/27-30/2008 |

Cryptotis merriami, Cryptotis pueblensis |

ECO-SC-M 2109, 2110 | 3 | 16.4883° | -93.3800° | Coffee plantation | 1,453 | 100 | 3 | 300 |

| 08/27-30/2009 | 5 Cryptotis griseoventris, Sorex cristobalensis |

ECO-SC-M 2177 - 2182 | 4 | 16.7203° | -92.7013° | Pine-oak forest | 2,330 | 150 | 3 | 450 |

| 09/01-03/2010 | 4 | Pine-oak forest | 2,400 | 100 | 2 | 200 | ||||

| 01/01/2011 | Cryptotis merriami | ECO-SC-M 4444 | 5 | 16.9116° | -93.6120° | High tropical forest | 779 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| 07/23/2011 | Cryptotis lacandonensis | ECO-SC-M 7951 | 6 | 17.1119° | -91.6221° | High tropical forest | 553 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| 09/06-09/2013 | 7 | Pine-oak forest | 220 | 120 | 3 | 360 | ||||

| 07/16-18/2014 | 2 Cryptotis pueblensis, Cryptotis mexicanus |

ECO-SC-M 7555, 7556, 7561 | 8 | 17.1343° | -93.1689° | Pine-oak forest | 1,600 | 100 | 2 | 200 |

| 07/17/2014 | Cryptotis mexicanus | ECO-SC-M 7574 | 9 | 17.1726° | -93.1386° | Cloud Forest | 1,780 | 100 | 1 | 100 |

| 01/12-15/2015 | 10 | Pine-oak forest | 2,120 | 100 | 3 | 150 | ||||

| 04/22-24/2015 | 11 | Fallow land/cloud forest | 1,350 | 100 | 2 | 200 | ||||

| 07/06-09/2015 | Cryptotis merriami | ECO-SC-M 7871 | 12 | 16.5034° | -93.3680° | Coffee plantation | 1,350 | 120 | 3 | 360 |

| 10/09-11/2017 | Cryptotis mexicanus | ECO-SC-M 8776 | 8 | 17.1343° | -93.1689° | Pine-oak forest | 1,600 | 100 | 2 | 200 |

| 06/08/2018-08/22/2018 | Sorex cristobalensis, Cryptotis griseoventris | ECO-SC-M 9114, 9179 | 4 | 16.7216° | -92.7005° | Pine-oak forest | 2,300 | 100 | 77 | 7,700 |

| 10/23-27/2018 | 13 | Cloud Forest | 2,500 | 180 | 4 | 720 | ||||

| Total | 22 | 117 | 12,340 |

Locality 1: Huitepec Ecological Reserve, Eastern slope, 2 km NE of San Cristobal de Las Casas. M. San Cristobal de Las Casas.

Locality 2: Huitepec Ecological Reserve, 5.5 km NW of San Cristobal de Las Casas. M. San Cristobal de Las Casas.

Locality 3: Cerro Brujo. 2.6 km S of New Simojovel. M. Ocozocoautla.

Locality 4: San Jose Biological Station. 6.6 km SW of San Cristóbal de Las Casas. M. San Cristobal de Las Casas.

Locality 5: 0.87 km SE of Emiliano Rabasa, RIB El Ocote. M. Ocozocoautla.

Locality 6: Métzabok Tourist Camp. M. Ocosingo.

Locality 7: Los Encuentros Ecological Park. M. San Cristobal de Las Casas.

Locality 8: Laguna Verde Nursery. 1 km W of Coapilla. M. Coapilla.

Locality 9: 5.6 km NE of Coapilla. Coapilla-Tapalapa Road. M. Coapilla.

Locality 10: El Madron. Fraccionamiento San Nicolas. 3.5 km SW of ECOSUR. M. San Cristobal de Las Casas.

Locality 11: Cerro Brujo. Comunidad Nuevo San Luis. 3.8 km SW of Nuevo Simojovel. M. Ocozocoautla.

Locality 12: Rancho El Porvenir. 1.65 km SW of Nuevo Simojovel. M. Ocozocoautla.

Locality 13: Huitepec Ecological Reserve, NNW slope, 2 km NE of San Cristobal de Las Casas. M. San Cristobal de Las Casas.

In order to estimate relative abundances per species of shrews in the total sampling, we obtained the values of total trapping effort (number of trap-nights) and the capture success (number of individuals/trapping effort x100) by species (Horvath et al. 2010). We recorded information on the type of habitat where each specimen was found and the potential threats observed for their survival. The taxonomic identification was conducted by comparing the specimens collected with voucher specimens deposited in the Mammal Collection of El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECO-SC-M) and the Colección Nacional of the Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (CNMA), as well as the identification keys by Woodman and Timm (1999) and Carraway (2007).

Also, we used the Global Biodiversity Information Facility database (GBIF 2018) downloaded on 3 September 2018 (https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.9wfkdg), to gather information about historical records of shrews of Chiapas deposited in scientific collections. The search criteria included the Order Soricomorpha (the updated name of the order is not currently active in the database) and the genera Sorex and Cryptotis, with all existing records. Subsequently, data were filtered according to country (Mexico) and then to state (Chiapas). Only those records with extensive information (locality, genus, species, collection catalog number, and geographic coordinates) were considered; subsequently, the nomenclature of some species was updated, and the location of each record across collection localities was confirmed using the ManisNet calculator (http://manisnet.org/; Wieczorek and Wieczorek 2015). The geographic coordinates of all shrew collection records were projected on a map of physiographic subprovinces (INEGI 1981), land use and vegetation of Chiapas based on INEGI series VI (2014-2017), in order to get a detailed identification of the distribution of each species in different types of vegetation and current land use.

Results

Shrews were captured in nine of the 13 sampling sites: three sites in the municipality of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, including the type locality for S. stizodon (Huitepec Ecological Reserve), three in the municipality of Ocozocoautla, two in Coapilla and one in Ocosingo. The trapping effort yielded 22 specimens of six species of shrews (number of specimens in brackets): C. griseoventris (7), C. pueblensis (4), C. merriami (4), S. cristobalensis (3), C. mexicanus (3), and C. lacandonensis (1; Table 1). The total trapping effort was 12,340 trap-nights, and the overall success of capture was 0.18. Of the total number of specimens captured, the relative abundance of C. griseoventris was the highest, with 31.81 % and a capture success of 0.056. It was followed by C. merriami and C. pueblensis, with a relative abundance of 18.18 % and a capture success of 0,032; S. cristobalensis and C. mexicanus, with a relative abundance of 13.63 % and a capture success of 0.024; and C. lacandonensis, with a relative abundance of 4.54 % and a capture success of 0.008.

Shrews were recorded in secondary vegetation of pine-oak forest (C. griseoventris, C. mexicanus, C. pueblensis, S. cristobalensis); secondary vegetation of cloud forest (C. merriami, C. pueblensis); secondary vegetation of high evergreen forest (C. lacandonensis, C. merriami); ranfed agriculture (S. cristobalensis); oak-pine forest (C. griseoventris); and pine-oak forest (C. pueblensis;Table 2; Figure 1).

Table 2 Number of historical records of shrews of Chiapas by type of vegetation and land use, obtained from scientific voucher specimens from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and field work records of (in parentheses). Types of vegetation and changes of land use: RA = Rainfed agriculture; HS = human settlements; OPf = oak-pine forest; Pf = pine forest; POf = pine-oak forest; CF = Cloud Forest; WB = water body; DV = devoid of vegetation; Pa = pasture; HMG = High mountain grassland; SVPf = secondary vegetation of pine forest; SVPOf = secondary vegetation of pine-oak forest; SVOf = secondary vegetation of oak forest; SVCF = secondary vegetation of cloud forest; SVTDf = secondary vegetation of tropical deciduous forest; SVHEf = secondary vegetation of high evergreen forest; UA= urban area.

| RA | HS | OPf | Pf | POf | CF | WB | DV | Pa | HMG | SVPf | SVOPf | SVOf | SVCF | SVTDf | SVHEf | UA | Grand total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptotis | 13 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 21 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 4 | 25 | 107 | |

| goodwini | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| griseoventris | 2(1) | 1 | 2 | (6) | 1 | 1 | 14 | |||||||||||

| lacandonensis | 2(1) | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| merriami | 5 | 2 | 1(3) | (1) | 1 | 13 | ||||||||||||

| mexicanus | 2 | (3) | 3 | 2 | 10 | |||||||||||||

| pueblensis | 4 | 3 | (1) | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 7(2) | 1(1) | 23 | 56 | ||||||

| tropicalis | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | ||||||||||||

| Sorex | 4 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 33 | |||||||||

| cristobalensis | 1(1) | 1 | 4 | 1 | 3(2) | 2 | 15 | |||||||||||

| chiapensis | 5 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 15 | ||||||||||||

| sclateri | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| stizodon | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Grand total | 17 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 28 | 1 | 18 | 3 | 4 | 26 | 140 |

Figure 1 Location of the species of shrews recorded in the state of Chiapas, by physiographic subprovince. AC = Altos de Chiapas; DC = Depresión Central de Chiapas; LLChG = Coastal plain of Chiapas y Guatemala; LLIs = Isthmus plain; LLPT = Plain and wetlands of Tabasco; SBP = Petén Low Sierras; SL = Sierra Lacandona; SNCh = Sierras of Northern Chiapas; SSCh = Sierras of Southern Chiapas; VC = Volcanoes of Central America.

In addition, 118 records for shrews were compiled from scientific collections dating back to 1895. Historical records of shrews correspond to different current types of habitat (Table 2; Figure 1). Current records of shrews in Chiapas are distributed in three of the 10 physiographic subprovinces, while there are historical records for six physiographic subprovinces (Table 3; Figure 1).

Table 3 Number of historical records of shrews of Chiapas by physiographic subprovince, obtained from scientific voucher specimens from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) and field work records of (in parentheses). Physiographic Subprovince: ACh = Altos of Chiapas; SL = Sierra Lacandona; DC = Central Depression of Chiapas; LLChG = coastal plain of Chiapas and Guatemala; SNCh = Sierras of Northern Chiapas; SSCh = Sierras of Southern Chiapas; VC = Volcanoes of Central America.

| ACh | SL | DC | LLCChG | SNCh | SSCh | VC | Grand total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptotis | 64 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 17 | 14 | 3 | 107 |

| goodwini | 2 | 1 | 3 | |||||

| griseoventris | 7 (7) | 14 | ||||||

| lacandonensis | 2 (1) | 3 | ||||||

| merriami | 9 (4) | 13 | ||||||

| mexicanus | 1 | 7 (3) | 11 | |||||

| pueblensis | 34 (2) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 5 (2) | 7 | 56 | |

| tropicalis | 5 | 2 | 7 | |||||

| Sorex | 10 | 4 | 17 | 2 | 33 | |||

| cristobalensis | 4 (3) | 6 | 2 | 15 | ||||

| chiapensis | 1 | 3 | 11 | 15 | ||||

| sclateri | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||||

| stizodon | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Grand total | 74 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 21 | 31 | 5 | 140 |

Discussion

Shrews are among the least represented mammals in scientific mammal collections and, therefore, among the least studied and known. Increasing the records of shrews requires a greater effort focused on this taxonomic group, using traps with a high capture success, such as pitfall traps (Umetsu et al. 2006). Unfortunately, little research is conducted in North and South America specifically dedicated to the scientific collecting of shrews; consequently, the records we know are actually the result of incidental sampling that targeted other groups of small mammals, such as rodents (Lorenzo et al. 2016). In this study and over 16 years (since 2002) we found records of 22 specimens corresponding to six species of shrews, three of them with remarkable records for being barely represented, or for expanding their previously known distribution area: C. griseoventris, C. lacandonensis, and C. merriami, plus three species that are considered common, namely C. mexicanus, C. pueblensis, and S. cristobalensis.

Noteworthy records. Cryptotis griseoventris (Guatemalan broad-clawed shrew). Previously considered as a subspecies of C. goldmani (Carraway 2007), it is the species with the highest relative abundance, located in cloud forest and pine-oak forest between 2,330 and 2,376 masl. However, there are few records of its distribution, so its biology and ecology are little known. The records reported here were deemed unique and novel, as only sporadic records were known since the last confirmed one more than 50 years ago (Guevara et al. 2014b). Besides, this species seemingly has a small distribution area (< 5,000 km2), above 2,100 masl. in cloud forests and pine-oak forests in Los Altos de Chiapas, Mexico, and is probably endangered due to the deforestation of its habitat and climate change (Guevara et al. 2014b).

Cryptotis lacandonensis (Lacandon forest small-eared shrew). This species was recently described and little is currently known about its distribution and biology (Guevara et al. 2014a). It thrives in the Lacandon forest, within the Yaxchilan archaeological zone at 90 masl. in the municipality of Ocosingo. It is known by only two specimens collected on 3 February 1999 by L. A. Escobedo-Morales and deposited in the Museum of Zoology “Alfonso L. Herrera” (type specimen MZFC 7168, type adult female; MZFC 7107) of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM; Guevara et al. 2014a). The record presented here corresponds to an adult female (ECO-SC-M 7951) and is the third known specimen of this species. This specimen was collected in the Métzabok tourist camp, municipality of Ocosingo, in a high tropical forest at 553 masl, thus expanding its distribution area by 74.23 km to the NW of the type locality (Yaxchilán Archaeological Zone, Chiapas; Guevara et al. 2014a; Figure 1). We believe long-term field work should be conducted to assess its current conservation status and distribution area, both in Mexico and in neighboring countries.

Cryptotis merriami (Merriam’s small-eared shrew). This species belongs to the C. nigrescens group of species, which is distributed from Chiapas and the Yucatan Peninsula down to northern South America, in addition to a pellet record from the state of Guerrero tentatively allocated to the C. nigrescens group (Lopez-Forment and Urbano 1977). It inhabits mountainous areas from Chiapas to Costa Rica, between 975 to 1,650 masl in pine-oak forest and agricultural areas near forests, and its biology is poorly known (Woodman et al. 2016a). Although it is considered a common species in Guatemala, there are only five known specimens by historical records in Chiapas: Mahosik, 32.18 km NE (Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, MVZ 141668); 30.4 km NE San Cristóbal de Las Casas, municipality of Tenejapa (MVZ 141671); Nabil, 28.96 km NE San Cristóbal de Las Casas, municipality of Tenejapa (MVZ 141669, MVZ 141670); 3.5 km N Las Margaritas, 1,493 m, Volcán Kagchina, municipality of Las Margaritas (Fort Hays Sternberg Museum Mammalogy Collection, FHSM 8779).

The specimens collected in this work belong to three different sampling sites in the municipality of Ocozocoautla in a high tropical forest between 588 and 779 masl, and in coffee plantations between 1,350 and 1.453 masl (Table 1; Figure 1). These records extend the distribution area in Chiapas by 122 km to the NW from the marginal record of Tenejapa, with the specimen collected at El Ocote; by 106 km to the SW with the two specimens collected at Cerro Brujo; and by 105 km to the SW with the specimen from Rancho El Porvenir. Also, these records extend the distribution area of the C. nigrescens group of species toward the north.

Records of common species. The records of C. mexicanus, C. pueblensis, and S. cristobalensis are consistent with the proposed geographic distribution for these species, as well as with the type of habitat and altitude.

Cryptotis mexicanus (Mexican small-eared shrew). This species is endemic to Mexico, distributed in mountains stretching from Chiapas to Tamaulipas (Guevara and Sánchez-Cordero 2018). This species is relatively common in cloud forest, pine-oak forest and forest edges between 520 and 2,600 masl (Cassola 2016). Records are located in cloud forest at 1,780 masl and pine-oak forest at 1,600 m (Table 1; Figure 1). Previously, C. mexicanus was only known through a single specimen from Los Altos, Chiapas, Mexico (Choate, 1970). According to Guevara and Sánchez-Cordero (2018), the Los Altos de Chiapas population may be differentiated at the species level from the population living west of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec; hence, these records are highly relevant for future taxonomic revisions.

Cryptotis pueblensis (Small-eared shrew from Puebla). It was previously considered as a subspecies of C. parvus (Whitaker 1974), distributed from eastern United States and southeastern Ontario, Canada, to eastern New Mexico and in northeastern, central and southern Mexico. Recently, C. parvus was divided into several species, one being C. pueblensis. This is regarded as a relatively common species that may be tolerant to some degree of habitat modification (Woodman et al. 2016b). Records are located in cloud forest at 2,400 masl, pine-oak forest at 1,600 masl., and coffee plantations at 1,453 masl (Table 1; Figure 1).

Sorex cristobalensis (San Cristobal shrew). This species belongs to the S. salvini group and has been considered as a subspecies of S. saussurei, S. veraecrucis and S. salvini (Woodman et al. 2012). Matson and Ordóñez-Garza (2017) escalated it to the species level. It is known from three localities in Chiapas from 1,900 to 2,560 masl, in high mountain forests (Matson and Ordóñez-Garza 2017). The records included here are located in cloud forest at 2,367 masl and pine-oak forest at 2,330 m (Table 1; Figure 1).

Lack of species records. No success was achieved in the capture of three species of widely distributed shrews that are common in mountainous areas of Chiapas above 1,200 masl. However, there are historical records of these species in Chiapas: Cryptotis goodwini found in central and eastern parts of Sierra Madre de Chiapas; C. tropicalis, in southeast Sierra Madre de Chiapas and southeast Central Depression; and Sorex chiapensis, in the southeastern Sierra Madre de Chiapas and Macizo Central. In all these areas, deforestation is a major threat while agricultural and urban development are potential threats (Woodman 2008; Cuaron and de Grammont 2017; Matson et al. 2017). It is imperative to perform sampling targeting these species throughout their distribution range in Chiapas and determine their current type of habitat, as well as to identify the current threats to their populations. Also, two species that are micro-endemic to Chiapas were not collected, namely S. sclateri and S. stizodon, which deserve special mention.

Sorex sclateri (Sclater’s shrew). This species inhabits the mountains in northern Chiapas, in Tumbalá, at 1,524 masl, municipality of Tumbalá. It is known from only five specimens, four collected from 23 to 25 October 1895 by E. W. Nelson and E. A. Goldman, deposited at the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution (USNM 75871, 75872 type specimen adult female, 75873, 75874; Merriam 1897; Carraway 2007) and one specimen collected on 19 April 1967 by A. Ramirez at San Antonio Buenavista, municipality of La Independencia, deposited in the Mammalogy Collection of Escuela Nacional de Ciencias Biológicas, Instituto Politécnico Nacional (ENCB 2860; Carraway 2007). This species has not been spotted within protected natural areas, implying considerable threats to its habitat due to the loss and fragmentation of its habitat resulting from changes in land use (livestock, agriculture and logging). The distance between the two known localities for this species is 143 km (in a straight line); both are found in different physiographic provinces with their own environmental conditions and vegetation. Advancing knowledge about their conservation status is currently limited by the social conflicts that are on the rise throughout the state (i. e., displacement of indigenous communities) and, in particular in the type locality, by the development of mining and land ownership issues; these aggravating circumstances make it impossible to carry out field work, although efforts have already been made.

Sorex stizodon (Pale-toothed shrew). This species is known only from a single specimen collected 124 years ago (25 September 1895) by E. W. Nelson and E. A. Goldman within a natural protected area, the Huitepec Ecological Reserve, at 2,743 m, municipality of San Cristóbal de Las Casas, and deposited in the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution (USNM 75885 type adult female; Merriam, 1895; Carraway 2007); hence, it has been considered as potentially extinct (Ceballos and Navarro 1991). Currently, there are strong environmental issues around this reserve, derived from human activities that threaten it from the outside, including the expansion of human settlements, invasions to the reserve, and change of land use to agriculture (Calderon et al. 2012; Morales et al. 2013). This situation is further aggravated by illegal logging and extraction of epiphytes inside the reserve (Enríquez and Rangel 2009), and by the presence of invasive species such as dogs and feral cats from the city of San Cristobal de Las Casas (Santiz 2018). For these reasons, we presume that, if a population still exists, its survival is severely threatened.

If the current trends regarding the modification of its habitat, and the pressure from the presence of invasive species, this species may become extinct in the short term. On the other hand, the life cycle of shrews (Cryptotis and Sorex) has a duration of between one and two years (Rudd 1955; Pfeiffer and Gass 1963; Owen and Hoffmann 1983; Choate et al. 1994; Laerm et al. 2007), meaning that an average of 92 generations have passed since this species was first discovered, with no single individual detected during this time; this is remarkable, as it is one of the criteria established by IUCN (2012) to list a species as extinct.

Scenario of future research for the conservation of shrews of Chiapas. All species of shrews of Chiapas are currently facing a serious conservation threat derived from the loss of habitat (cloud forests, pine-oak forests and tropical forests) by deforestation, which shows annual rates above 3 % in the state (Soto-Pinto et al. 2012) and from the anthropogenic climate change. Changes in the distribution and abundance of some species of shrews may be affected by changes of land use from forests to crops and pastures intended for agricultural and livestock activities (Naranjo et al. 2016). Examples of this phenomenon are the degree of disturbance of the original vegetation and that some historical records of shrews are located in currently altered vegetation types, such as rainfed agriculture, secondary vegetation, areas devoid of vegetation, as well as human settlements and urban areas; we do not know whether the original populations are still present in these areas. Within mammals, shrews are amongst the groups with the lowest dispersal capability; therefore, these are highly vulnerable to habitat transformation and climate change (Urban et al. 2013). A key aspect that deserves evaluation is the extent to which these changes affect populations of micro-endemic shrews, as is the case of S. sclateri in agricultural areas and S. stizodon around human settlements. Also, the displacement of opportunistic mammals (e. g., domestic rodents, cats and dogs; Naranjo et al. 2016) driven by the changes in vegetation threaten the survival of the populations of shrews.

Field studies should be promoted, since the intensive and targeted field monitoring will allow considering whether the species of shrews of Chiapas are indeed absent in areas where these were previously recorded, assessing their conservation status, redefining their risk category, and even determining whether these are already extinct in the wild. It is important to communicate the results of biological scientific investigations of the species of shrews of Chiapas to various sectors of society and decision-makers. It is also highly important to preserve and properly manage the habitat where shrews thrive, create and maintain biological corridors, and promote realistic alternatives for the sustainable use of wild flora and fauna involving the participation of the local communities to improve the local economy, i. e., through the promotion of in situ instruments of environmental policy (Naranjo et al. 2013, 2016). If a feasible conservation strategy is not implemented, the loss of the diversity of shrews in Chiapas will be unavoidable.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)