Introduction

The quantity and quality of the road infrastructure are key economic growth drivers, facilitating access of inhabitants to health and education services, besides contributing to reduce poverty (Bird et al. 2011). In Mexico, investment in road infrastructure is considered a strategic issue, since it fosters economic growth and development. It is one of the cornerstones of competitiveness and social well-being, supporting economic growth and regional development, and reducing transportation costs (Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos, 2014). However, roads involve multiple negative environmental effects, including pollution, habitat fragmentation, and deforestation, as well as wildlife mortality from roadkill events (Forman et al. 2003).

In particular, wild cats are affected to a large extent by roads (Kerley et al. 2002; Ngoprasert et al. 2007; Ford et al. 2010; Jansen et al. 2010; McGuire 2012; Basille et al. 2013), as these mammals typically have large home ranges and roam long distances (Macdonald et al. 2010b), in addition to being low tolerant to human disturbance (Macdonald et al. 2010a). These attributes increase the vulnerability of these species to the effects of roads and traffic (Grilo et al. 2015). Mortality associated to road collisions has been reported for several felids [e.g. tiger (Panthera tigris) Gruisen 1998a, b; lion (Panthera leo) Drews 1995; Iberian lynx (Lynx pardinus) Simon et al. 2012], leading to significant effects on the conservation of some species such as the Iberian lynx and subspecies as the Florida puma (Puma concolor coryi: Taylor et al. 2002).

Mexico is home to six felid species: Herpailurus yagouaroundi (jaguarundi), Leopardus pardalis (ocelot), L. wiedii (margay), Lynx rufus (bobcat), Puma concolor (puma) and Panthera onca (jaguar; Ramírez-Pulido et al. 2014). The effect of roads on felids has focused on the jaguar, both in Mexico and throughout its distribution range, finding that these negatively affect its mobility and dispersal (Ortega-Huerta and Medley 1999; Conde 2007; Conde et al. 2010; Colchero et al. 2011; Pallares et al. 2015; Stoner et al. 2015; Cullen et al. 2016; Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017). At the continental level and particularly in Mexico, P. concolor and H. yagouaroundi are considered to be species exposed to high road densities, and hence to their negative effects, including death by vehicle collision (Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017). For L. pardalis, L. wiedii and L. rufus there are no specific data on the potential effect of roads on their populations in Mexico.

There are literature reports of roadkill events outside of Mexico involving the six felid species (e. g., H. yagouaroundi, Cunha et al. 2010; Hegel et al. 2012; Arias-Alzate et al. 2013; Giordano 2015; L. pardalis, Cáceres et al. 2010; L. wiedii, Carvalho et al. 2014; P. concolor, Maehr et al. 1991; Cáceres et al. 2010; P. onca, Srbek-Araujo et al. 2015). However, in Mexico no felids have been reported in publications addressing road-killed wildlife (see González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013); the few sporadic records come from studies on the distribution of species rather than the effect of roads as such (e. g., Meraz et al. 2010; Almazan-Catalan et al. 2013).

At the global level, a large amount of information on roadkilled wildlife is available in informal information sources including news in the local press, anecdotal evidence or records in informal unpublished technical reports (Smith and van der Ree 2015), and more recently also in social websites (Shilling et al. 2015). No studies have been conducted to date to gather information from informal media such as citizen science websites to assess felid roadkill events in Mexican roads. In addition, despite the fact that information systems have been put in place in Mexico for the systematic recording of wildlife road kills (e. g., Naturalista by CONABIO http://www.naturalista.mx/ and Observatorio de Movilidad y Mortalidad de Fauna (Wildlife Mobility and Mortality Observatory) by SCT/IMT http://watch.imt.mx ), these have not been fully developed, unlike other countries (e. g., URUBU System in Brazil http://sistemaurubu.com.br/es/; California Roadkill Regitration System in USA http://www.wildlifecrossing.net/california/; Shilling et al. 2015).

The collection of information on the number of road-killed felids and the regions where these are killed in Mexico is of great importance for the conservation of these species, as four of the six felid species are listed in one of the protection categories established in the Mexican regulations (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010), and roadkill mortality adds to other anthropogenic causes (e .g., hunting, loss of habitat, human-carnivore conflicts, etc: CONANP 2009). From the above, the objective of this work was to carry out a review of the records regarding felid roadkill events in Mexico, from formal and informal sources, sorting them systematically according to their origin (time and place of occurrence).

Materials and Methods

Study Area. The survey of felid roadkill records comprised all mexican territory. The country has a road network of approximately 156,797 km (141,545 km of two-lane roads and 15,252 km of highways with more than two lanes; SCT 2016) traveled by a fleet of 27,500,000 vehicles (INEGI 2017). The distribution range of the six species of wild cats living in Mexico is very broad (Hall 1981), so that P. concolor is potentially found throughout the country, while P. onca, L. pardalis, L. wiedii and H. yagouaroundi are distributed in tropical areas, and L. rufus in mostly temperate areas.

Methods. Information on felid roadkill events in Mexico was obtained through a systematic search of confirmed records of wild cats killed by cars in Mexico in the scientific literature, mammal collection records, online news, and emails addressed to specialists in conservation and management of mammals, especially wild cats. The information gathered from each of the records of road-killed felids included species, road or town closest to the collision site, state of Mexico where the incident occurred, year, type of information source, and reference. The survey aimed at obtaining an annual overview of the sources of these records, discarding those with uncertain date. Two types of information sources were surveyed, i. e. published and non-published; the first can be consulted and the second has added reliability through consultation with specialists. Within these two categories, the following media were searched:

Scientific literature. The survey included published articles and theses using specialized webpages like Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com.mx) and Web of Science (https://www.webofknowledge.com/). In each of these sites, the search criteria used were the felid species (common and scientific name) and the word hit/struck/road-killed in both English and Spanish. Once a record was identified, this was reviewed to determine the type of record. A felid roadkill record was deemed valid if it explicitly referred to the record of a hit animal, in addition to providing specific information on place and date. In the case of bachelors or graduate theses, the record was determined as valid only when a photograph of the struck specimen was included, provided the author could confirm the cause of death.

Mammal Collections and Citizen Science websites. Information was requested from curators of 28 collections listed in the Asociación Mexicana de Mastozoología A. C. (Lorenzo et al. 2006), particularly regarding collection site and year of recording, about any of the six Mexican wild cat species that were collected and deposited in the collection after being hit. Also, each field record in the NaturaLista webpage (http://www.naturalista.mx/) was reviewed to identify the road-killed specimens.

Internet media. The Google web browser (http://www.google.com) was extensively surveyed for informal published records of road-killed felids (e. g., news about specific roadkill events mentioned in national or local news media, personal web pages or social networks, and reports from the web pages of non-governmental organizations). The search was conducted using the following key words: common name + road-killed, species + road-killed, common name + Mexico, species + Mexico, species + road, common name + road, in both Spanish and English. Once a record was identified, the original source was reviewed, and the quality of the information assessed based on the presence/absence of photographs of the event, as well as its geographic location.

Emails addressed to specialists (personal communications). Through e-mails sent to specialists in wild cats and wildlife conservation in Mexico working in Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), universities and government authorities, information was requested on specific events involving struck felids that these specialists witnessed or on which they had specific information. Once the specialist was contacted, specific data were requested regarding species, year and location of the roadkill event, as well as any photograph of it, if available. These records were classified into personal communications or obtained from a NGO.

Data Analysis. The records of road-killed felids were entered into a database by species in phylogenetic order (Prevosti et al. 2010) and classified first by origin, in accordance with the source of information (scientific literature, collections, online news or specialists). From the geographical standpoint, records were classified according to the state where the roadkill event occurred. It was decided that the analysis would be conducted by state, since many of the observations (from published and unpublished sources) had no precise data of the specific locality or road segment where the event occurred.

The first stage of the analysis compared roadkill data (dates and sites) obtained from the various sources of information, in order to identify potential duplicate records. Subsequently, it was investigated whether the felid roadkill sites matched the distribution range of the species in Mexico. To this end, the presence/absence of felid roadkill events obtained from all information sources in each state of the country was determined by species and compared in a Geographical Information System versus the range reported for the respective species (Hall 1981) from the Digital Distribution Maps of the Mammals of the Western Hemisphere v. 3.0 (Patterson et al. 2007).

The next stage of the analysis was to determine whether felid roadkill events are related to road density. A positive relationship between road density in a region and the number of medium-sized mammal roadkill events has been observed (Saeki and Macdonald 2004). In Mexico, the national road network is not evenly distributed; instead, important regional differences occur in the density of roads across the different states of the country (Deichmann et al. 2004). The surface area in km2 (INEGI 2015) and the length of roads (km) in state were obtained (SCT 2016). Road density per state was calculated by dividing the total number of km of roads by the surface area of each state. The relationship between road density and the number of felid roadkill records per state was investigated through a Spearman’s rank correlation (Siegel and Castellan 1988); road density per state was associated with the number of felid roadkill events for each state considering all the sources of information used.

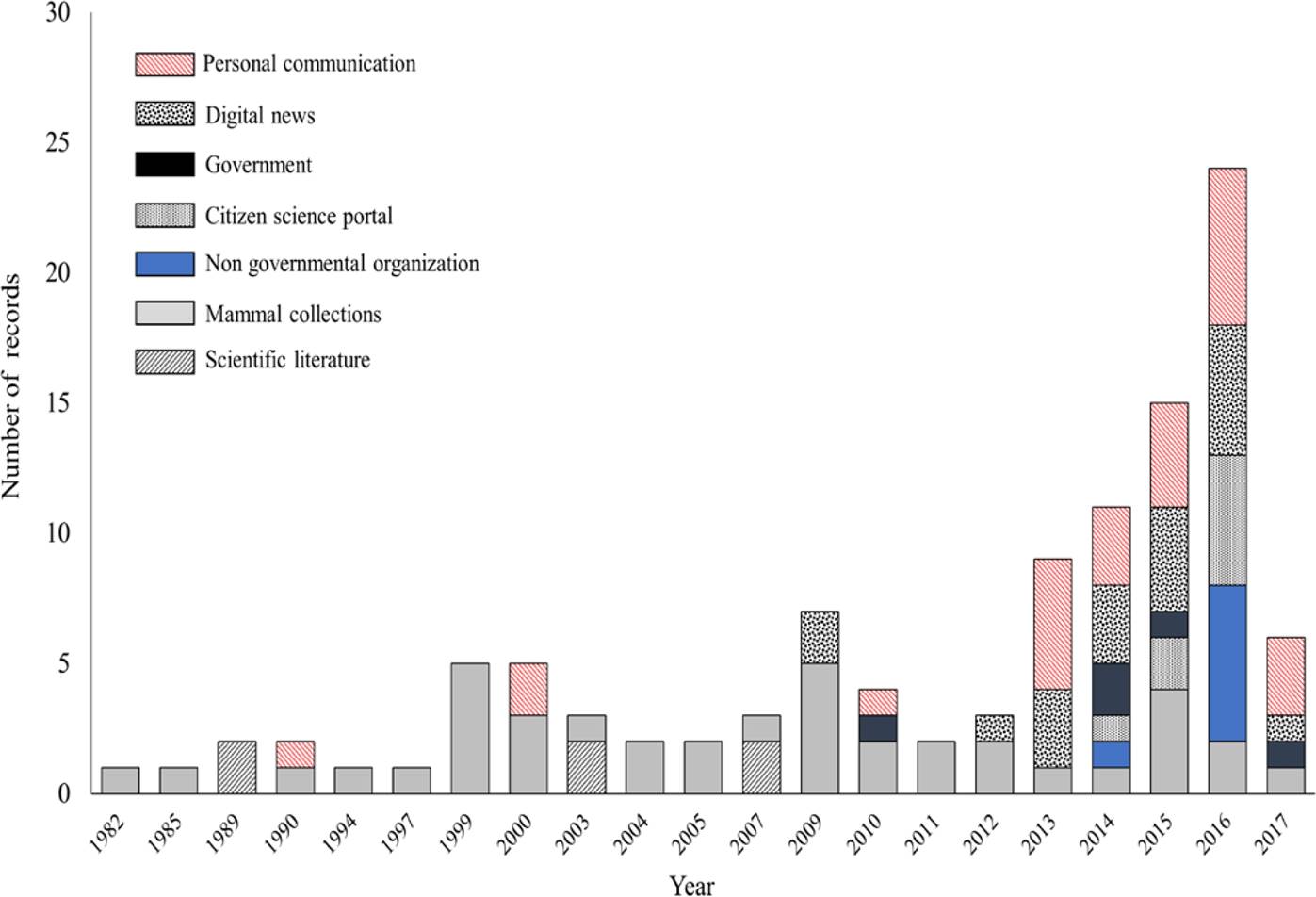

We analyze the data on an annual basis according to the source of information, to identify any changes in the trends in data recording during the period covered by the study. We excluded from the analysis those years were information was not available.

Results

The review revealed the existence of records of road killedfelids dating back to 1982. A total of 115 records of roadkill events was found for the six felid species living in Mexico (Supplementary Material 1, Figure 1). The number of roadkill records found were: H. yagouaroundi, 21; L. pardalis, 20; L. wiedii, 11; L. rufus, 50; P. concolor, 5; and P. onca, 8 (Figure 2). Of all records, 90 came from publications (academic and news, 78.2 %) and 25 were obtained through personal communications (21.7 %). Within published news (online or printed), 40 (34.8 %) came from scientific collections, 9 (16.5 %) from the local press, 10 from citizen science through CONABIO’s Naturalista webpage (8.7 %), nine (7.8 %) from peer-reviewed publications, seven (6.1 %) from NGOs, and five (4.3 %) from government agencies (Table 1).

Figure 1 Total number of records of felid roadkill events in Mexico by state. The figure includes the sum of records of Herpailurus yagouaroundi, Leopardus pardalis, L. wiedii, Lynx rufus, Puma concolor and Panthera onca obtained from published (mammal collections, scientific literature, government, citizen science web page, NGOs, digital news) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation) from 1982 to 2017.

Figure 2 a) Specimen of Herpailurus yagouaroundi recorded on La Ventosa road, Oaxaca. Photograph: Alejandro Tepatlán Vargas. b) Specimen of Herpailurus yagouaroundi recorded on the Tizimín road, Yucatán. Photograph: Diana F. Zamora Bárcenas. c) Specimen of Leopardus pardalis recorded near the Federal Highway 85, Ejido Miguel Hidalgo, Tamaulipas. Photograph: Milton Gildardo Ruiz-Bautista. d) Specimen of Leopardus pardalis in the Puerto Morelos - Playa del Carmen road. Photograph: Victor Castelazo-Calva. e) Specimen of Leopardus wiedii recorded near the Federal Highway 74 in Nayarit. Photograph: Mark Stackhouse. f) Specimen of Lynx rufus on a road in the border between the states of Queretaro and Guanajuato. Photograph: Diana F. Zamora Bárcenas. g) Specimen of Lynx rufus in the Federal Highway 7D El Sueco, Chihuahua. Photograph: Mircea Hidalgo Mihart. h) Runover specimen of Panthera onca near the Sabancuy-Champoton road, Campeche. Photograph: Marco Sánchez (CONANP, Laguna de Términos).

Table 1 Number of records of the six wild cat species struck in Mexico, classified according to the source of the record. Mammal Collection (MC), scientific literature (SL), citizen science web page (CSW), report in government media (RGM), digital news (DN), non-governmental organization (NGO), personal communication (PC).

| Source of the record | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | MC | SL | CSW | RGM | DN | NGO | PC | Total |

| Herpaiulurus yagouaroundi | 3 | 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 21 |

| Leopardus pardalis | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 20 |

| Leopardus wiedii | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 11 |

| Lynx rufus | 28 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 50 |

| Puma concolor | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 5 |

| Panthera onca | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

| Total (% of total) | 40 (34.78 %) | 9 (7.83 %) | 10 (8.70 %) | 5 (4.35 %) | 19 (16.52 %) | 7 (6.09 %) | 25 (21.74 %) | 115 |

Roadkill events were recorded in 25 of the 32 states of Mexico (Table 2, Figure 1). The comparison of the distribution area with the location of roadkill records for a given species reveals that there are states with no roadkill reports in spite of being included in the distribution range of the species (Figure 4). Roadkill events reported are as follows: H. yagouaroundi, 10 of the 15 states where it lives (10/15; 45 %); L. pardalis, 10/25 states (40 %); L. wiedii, 7/20 (35 %); and L. rufus, 11/27 (41 %). In the case of P. concolor, although this species is distributed throughout all of Mexico, roadkill events are recorded in three states only (Jalisco, Durango and Sonora, 9.4 %). Events involving P. onca are reported in four (Quintana Roo, Campeche, Veracruz, and Jalisco) of the 27 states where the species is distributed (15 %).

Table 2 Roadkill records by species and distribution range of the respective species in each state of Mexico. Roadkill records for each species were obtained from published (90) and unpublished sources (25). The presence of the species in each state was obtained from overlapping Hall’s distribution polygons (Hall 1981) for each species on the political division map of the Mexican Republic. The letter “P” indicates that the species is present in the state. “A” indicates that there are roadkill records for the species in the state. As regards the number of species per state, the first column corresponds to the presence and the second to records of struck species.

| State | Herpailurus yagouaroundi | Leopardus pardalis | Leopardus wiedii | Lynx rufus | Puma concolor | Panthera onca | Number of species per state | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aguascalientes | P | P | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Baja California | P | P | P | 3 | 0 | |||||||||

| Baja California Sur | P | A | P | 2 | 1 | |||||||||

| Campeche | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 5 | 4 | |||

| Chiapas | P | A | P | P | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Chihuahua | P | P | P | A | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Coahuila | P | P | P | P | 4 | 0 | ||||||||

| Colima | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Ciudad de México | P | P | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Durango | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Estado de México | P | A | P | P | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Guanajuato | P | P | 2 | 0 | ||||||||||

| Guerrero | P | A | P | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Hidalgo | P | P | P | P | P | 5 | 0 | |||||||

| Jalisco | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | P | A | 6 | 6 |

| Michoacán | P | A | P | P | P | A | P | P | 6 | 3 | ||||

| Morelos | P | P | P | A | P | P | 5 | 1 | ||||||

| Nayarit | P | P | P | A | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Nuevo León | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Oaxaca | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | P | P | 6 | 3 | |||

| Puebla | P | P | P | P | A | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Querétaro | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Quintana Roo | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | A | 5 | 3 | ||||

| San Luis Potosí | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Sinaloa | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Sonora | P | P | P | A | P | A | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Tabasco | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | ||||||

| Tamaulipas | P | P | A | P | P | P | P | 6 | 1 | |||||

| Tlaxcala | P | P | P | P | 4 | 0 | ||||||||

| Veracruz | P | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | A | 6 | 3 | |||

| Yucatán | P | A | P | A | P | P | P | 5 | 2 | |||||

| Zacatecas | P | A | P | P | 3 | 1 | ||||||||

| Total | 22 | 10 | 25 | 10 | 20 | 7 | 27 | 11 | 32 | 3 | 27 | 4 | ||

Figure 3 Records of each of the road-killed felid species in Mexico by state, showing the distribution range of each species from Hall (1981; in gray). Sum of records for each species obtained from published (scientific literature, mammal collections, digital news, government, citizen science portal or NGO websites) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation) from 1982 to 2017. a) Herpailurus yagouaroundi, b) Leopardus pardalis, c) Leopardus wiedii, d) Lynx rufus, e) Puma concolor, and f) Panthera onca.

Figure 4 Number of records of road-killed felids according to their origin as obtained from published (scientific literature, mammal collections, digital news, government, citizen science portal or NGO websites) and unpublished sources (personal communication with experts in wild cat conservation).

An inverse relationship was observed between road density by state and number of felid roadkill events registered (Rho=-0.35658, P = 0.04515). I. e. a lower road density is apparently associated with more events. Examples are Baja California Sur, with a road density of 0.8 km/km2 and 18 records; and Tlaxcala, with a high road density of 0.73 km/km2 and no roadkill records. Not all states show this same behavior, such as Chihuahua, with the lowest road density (0.05 km/km2) and no roadkill records, or Jalisco, with a road density of 0.36 km/km2 and 10 roadkill records.

The analysis of roadkill records and their sources (Figure 4) was conducted with 109 accurately dated records (6 records with no date were excluded). The period 1982-2017, comprising 35 years, included 21 years with roadkill records. The period 1982-2006 reported 25 felid roadkill records, 88 % from collections and scientific literature and the rest from personal communications. From 2007 to date 84 records were reported, 27.4 % from a collection or the scientific literature, and 72.6 % from other sources (22.6 %, online news; 26.2 %, personal communications).

Discussion

Among mammals, carnivores are the group most adversely affected by roadkill events (Rytwinski and Fahrig 2015; Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017), with well-documented cases, particularly in wild cats (e. g., Ferreras et al. 1992; Taylor et al. 2002). In Mexico, up until this report, no estimates of the number of roadkill events involving wild cats in the country was available to document the potential impact of this phenomenon on the conservation of the species. However, we now know that at least 115 individuals of the six species were killed by vehicle collision events between 1982 and 2017.

No records involving wild cats are reported in specific works on the quantification of roadkill events in Mexico (González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013), suggesting sporadic collision of these species by vehicles. However, despite the important efforts carried out in studies about animals killed on mexican roads, these have focused on a few road stretches and involving short periods of time (e .g., Morales-Mavil et al. 1997; Grosselet et al. 2008; González-Gallina et al. 2013; Pacheco-Figueroa et al. 2013), hence limiting its impact when seeking to understand the dynamics of this phenomenon at the national level (González-Gallina and Benítez-Badillo 2013). The information survey in different media allowed to establish the incidence of this phenomenon despite the absence of reports specifically mentioning felids in formal road surveys. This work points to the states where this type of studies should be conducted to gather further information.

It has been proposed that the vulnerability of wildlife species such as felids increases directly with road density (Cullen et al. 2016). Particularly for Mexico, the northeast and south-southeast regions of the country were identified as areas where several species of wild cats are exposed to high road densities (Ceia-Hasse et al. 2017). Despite the above, there are states for which just a few roadkill events, if any, have been reported, despite the fact that extensive areas of their territories are part of the distribution range of several species (e. g., Coahuila and Baja California), while others report a high number of struck specimens (i. e., Baja California Sur) in spite of the low road density (0.08 km/km2). This parameter alone does not entirely explain the distribution of roadkill records. Another factor affecting this distribution relates to the existence of professionals or institutions interested in keeping records of roadkill events. Mammal collections were the main source of felid roadkill records (34.8 % of the total number of records), the states with the highest number of records being those associated with a scientific collection, mostly when it focuses on the study of the local or regional fauna. This is the case of the comparison between the records in Baja California Sur (road density 0.08 km/km2) and Baja California (0.17 km/km2). Baja California Sur reports the largest number of wild cat roadkill events, with all records coming from the mammal collection of the Centro de Investigaciones del Noroeste (CIBNOR), while Baja California, in spite of sharing many of the ecological and environmental conditions with the neighboring state (Morrone and Márquez 2003), has no records of struck felids, probably because there are no groups of professionals interested in the subject.

Our results showed that 72.2 % of the records came from published sources available for consultation through formal searches (mammal collections or scientific publications); this finding strengthens the proposal that as regards roadkill events, information surveys should always involve information from non-formal sources (Smith and van der Ree 2015). However, although many of the records of road-killed felids in Mexico referred to H. yagouaroundi, L. rufus and P. concolor (65.2 % of records), in less formal media — particularly online media — a high percentage of the records (73.7 %) are related to L. pardalis, L. wiedii, and P. onca. This can be explained by the fact that there are animal species that capture the attention of the public (Clucas et al. 2008). This is the case of wild cats with stripped or spotted fur (e. g., L. pardalis, L. wiedii and P. onca), which are conspicuous and are part of the Mexican culture and traditions (Saunders 2005), added to the fact that governmental and non-governmental organizations have disseminated their importance and conservation status (SEMARNAT 2009). This is the case of the jaguar, a species that recorded five roadkill records in the state of Quintana Roo (Supplementary Material 1) from news media and that has been followed up for being a species with public appeal, i. e. a news target.

The growth of electronic and online media, as well as the use of smartphones, has facilitated the spreading of news on wildlife roadkill events (Shilling et al. 2015). In this work, we observed a steady increase in the number of felid roadkill records over the past 10 years, with the largest growth in records in digital news. The growth in the number of smartphone users (from 50.6 million users in 2015 to 60.6 million in 2016; INEGI 2016), coupled with the creation of specific platforms for the recording of roadkill incidents — such as Fauna Silvestre Atropellada y Fauna Atropellada del Noreste (Road-killed Wildlife and Northeastern Road-killed Wildlife) available in the NaturaLista platform, or the Observatorio de Movilidad y Mortalidad de Fauna (Observatory of Wildlife Mobility and Mortality) —, promote the recording of a growing number of reports, as has happened in other countries (Olson et al. 2014; Vercayie and Herremans 2015; Shilling et al. 2015). In this work, only 8.7 % of the records of road-killed cats came from citizen science projects. The advancement of information systems through these projects would facilitate the registration on roadkill events, not only of felids but also of other wild mammal species at the country level. The ease of communication by electronic means may potentially improve data quality in the monitoring of roadkill events by professionals (Olson 2014), provided the analyses consider the limitations that are intrinsic to the type of information collected (e. g., variable sampling effort, bias toward larger and more visible species, among others; Sarda-Palomera et al. 2012).

This work shows that data on road-killed wild cats is an underestimation, since a large number of these events are not recorded. It is therefore imperative to determine whether this type of events affects the different wild cat species at the population level to the extent that may threaten their long-term survival. The majority of wild cat species are listed in a risk category (NOM-059-SEMARNAT-2010), and several are considered as in danger of extinction (L. pardalis, L. wiedii and P. onca). Collisions with vehicles add to other mortality factors such those coming from habitat loss or conflicts with livestock (CONANP 2009), and could be even more important (Simon et al. 2012, Taylor et al. 2002). The surveillance of roadkill events through systematic long-term monitoring may lead to more effective mitigation measures (Grilo et al. 2015). This work should serve as a forewarning to stimulate the development of monitoring efforts and appropriate mitigation measures for these animals at the national level.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)