Introduction

The genus Galea Meyen 1833, with five living and two extinct species, is one of the most diverse genera within the Family Caviidae (Ubilla and Rinderknecht 2014; Dunnun 2015). Its fossil record dates back at least to the Ensenadense (Vucetich etal. 2015) and is composed mainly of fragmentary cranio-mandibular remains (Ubilla and Rinderknecht 2014). The only two known extinct species (i. e., G. orthodonta Ubilla and Rinderknecht 2001 and G. tixiensis Quintana 2001) are based on well preserved cranioden-tal and postcranial remains. The former of these species, G. orthodonta, has been found in Pleistocene sediments of Uruguay and southern Bolivia (Ubilla and Rinderknecht 2001; Ubilla and Rinderknecht 2014). The second extinct species, Galea tixiensis, was established from remains accumulated throughout the Holocene in rocky outcrops in the southeast of Province of Buenos Aires, in east-central Argentina (Quintana 2001). The materials that led to the description of G. tixiensis were instead referred to as either Galea sp., G musteloides or G. cf. musteloides (e. g., Tonni et al. 1988; Quintana and Mazzanti, 1998; Quintana 2001), highlighting its morphological similarity with individuals of the recent populations inhabiting this same region, firstly referred to G. musteloides and now allocated within G. leucoblephara (Dunnun 2015). Quintana (2001) indicated several diagnostic traits for Galea tixiensis (see below), in addition to larger size relative to other species in the same genus. Unfortunately, Quintana (2001) did not document what living specimens were compared against the fossil samples, nor some other relevant aspects that are key for the description of a new species, such as holotype measurements (which were not illustrated either). More recently, a species related to G. tixiensis, referred to as G. aff. tixiensis, was mentioned for the Pleistocene of Province of Corrientes, in northeast Argentina (Francia etal. 2012).

The examination of a vast number of specimens as part of a qualitative and quantitative morphologic review of the genus Galea allows us to assume that many of the diagnostic traits of G. tixiensis are not unique to this species, and neither is the combination of these traits (see also Ubilla and Rinderknecht 2014).The taxonomic status of G. tixiensis is relevant for several reasons (e. g., biogeographic, evolutionary), but mainly because, should this be a distinct species, it would be one of the eight species of mammals that became extinct over the past 500 years in mainland South America (cf. Teta et al. 2014; Prevosti et al. 2015).

The aim of this work is to review the taxonomic status of Galea tixiensis. Based on qualitative and quantitative morphological evidence, it is hypothesized that G. tixiensis is synonym for Galea leucoblephara Burmeister 1861.

Materials and Methods

We studied 110 specimens of Galea leucoblephara, including skulls and mandibles, from Argentina, Bolivia and Paraguay. These are deposited in the following collections (for details, see Appendix 1): CFA, Collection of Mammals of Fundación de Historia Natural Félix de Azara (Buenos Aires, Argentina); CMI, Collection of Mammals of Instituto Argentino de Investigación de Zonas Áridas (Instituto Argentino de Investigaciones de Zonas Áridas, Mendoza, Argentina); CML, Collection of Mammals of Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo (Facultad de Ciencias Naturales e Instituto Miguel Lillo, San Miguel de Tucumán, Argentina); CNP, Collection of Mammals of Centro Nacional Patagónico (Centro Nacional Patagónico, Puerto Madryn, Argentina) MACN-Ma, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales "Bernardino Rivada-via" (Buenos Aires, Argentina) MNHNP, Collection of Mammals of Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Paraguay (Asución, Paraguay); UACh, Collection of Mammals of Universidad Austral de Chile (Valdivia, Chile). Samples were grouped into 3 major geographical groups, allocated to subspecies G. leucoblephara demissa, G. l. leucoblephara and G. l. littoralis, following the taxonomic scheme proposed by Bezerra (2008) and Dunnun (2015). The first of these taxa is distributed across the lowlands of southeastern Bolivia and western Paraguay to the Provinces of Santiago del Estero and Catamarca in Argentina; the second, from southern Cat-amarca to Córdoba and northern Mendoza and San Luis, in Argentina; and the third, from southern Mendoza, La Pampa and southeastern Buenos Aires to northeastern Santa Cruz, in Argentina.

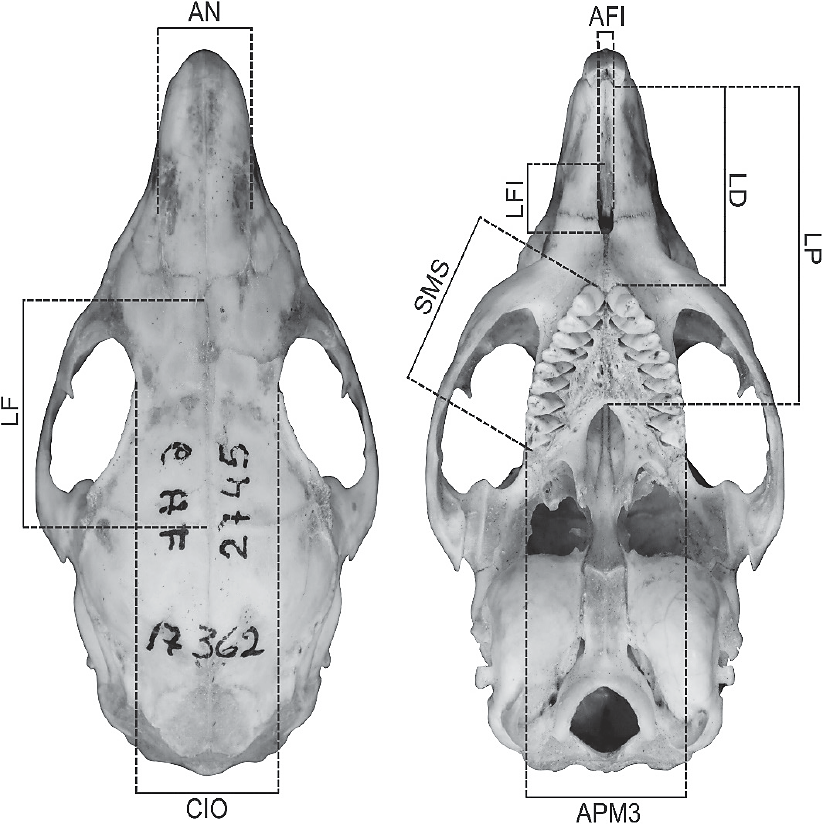

The following cranial measurements were recorded for each adult specimen (classes 3-5; cf. (sensu Bezerra 2008) (using a digital caliper accurate to 0.01 mm): AN = nasal width; CIO = interorbital constriction; FL = frontal length; LD = diastema length; AFI = incisive foramen width; LFI = incisive foramen length; LP = palatilar length; SMS = length of the upper toothrow length (alveolar); APM3 = palate width at the third upper molar. The measurements of the holotype of G. tixiensis were estimated using the software tpsdig2 from photographs in Bezerra (2008) and Francia et al. (2012), using as reference the scale in the latter.

To summarize the causes of morphometric variation and rank them according to importance, a principal components analysis (PCA) was performed from a variance-covariance matrix of the log-transformed measures. Previously, each individual measurement was corrected by the geometric mean of each individual to avoid the distortion derived from the effect of size (for this methodology, see Meachen-Samuels and Van Valkenburgh 2009). For the purposes of this work, form is defined as the appearance, configuration or composition of the traits, including size, whereas figure refers to the form excluding size (Vizcaíno et al. 2016). This is consistent with the approach of Richtsmeier et al. (2002), in his attempt to circumvent the use of these terms in the colloquial sense.

The anatomical terminology corresponds to the one used by Cherem and Ferrigolo (2012). The qualitative and quantitative morphological traits of Galea tixiensis were taken from the literature (i. e., Quintana 2001) and discussed from the comparison with recent specimens.

Results

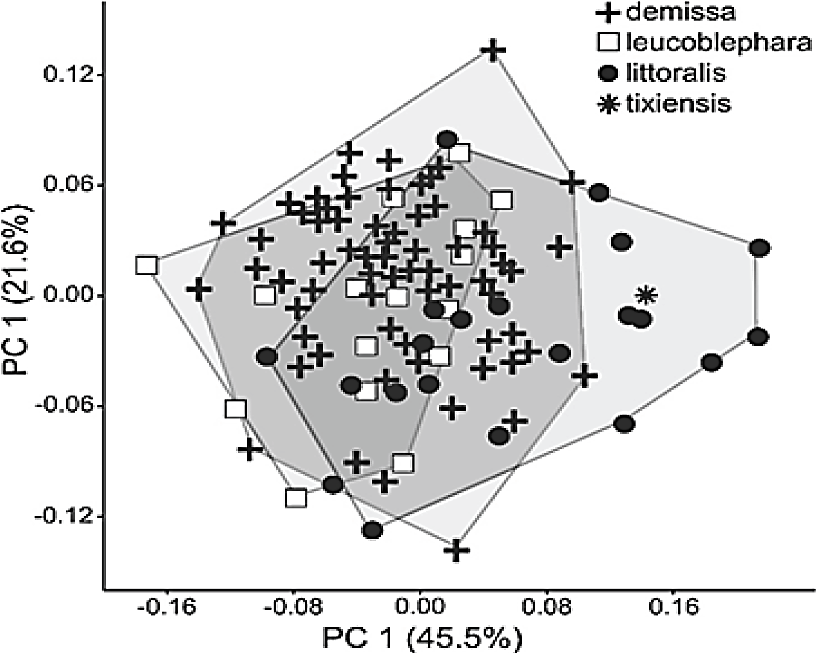

The first two PCA axes accounted for 63.1% of the variation in craniodental measurements (Figure 2; Table 2). The overlap of the polygons corresponding to the three subspecies currently recognized was moderate to high, suggesting that there are no major differences in figure. In this context, the holotype of G. tixiensis was allocated with G. l. littoralis specimens (Figure 2), toward positive values in PC 1. All the variables were negatively correlated with PC 1, except AFI, which was positively correlated.

Figure 1 Cranial measurements used in this study, shown on a skull of Galea leucoblephara (MACN 17362). For a reference of the abbreviations, see Materials and Methods.

Figure 2 Polygons and individual scores for adult specimens (n = 111) in three subspecies of Galea leucoblephara and the holotype of G. tixiensis for principal components 1 and 2 (obtained from a variance-covariance matrix on nine craniodental measurements corrected by the geometric mean).

Table 1 Statistical summary for nine craniodental measurements (in mm; for a reference of the abbreviations, see Materials and Methods) in adult specimens of the genus Galea.

Other abbreviations: N = number of specimens measured; SD = standard deviation; Min = minimum recorded value; Max. = maximum recorded value.

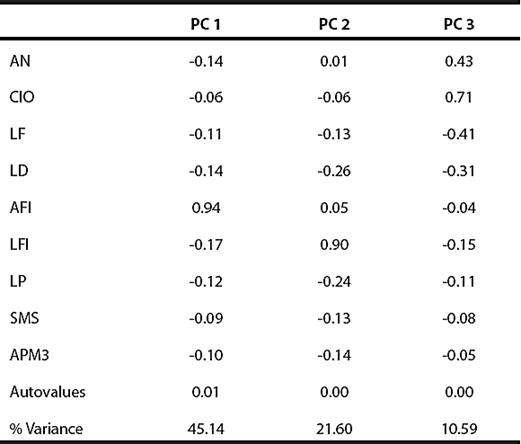

Table 2 Results of the principal component analysis performed on adult individuals (n = 111) of three subspecies of Galea leucoblephara and the holotype of G. tixiensis. For a reference of the abbreviations, see Materials and Methods.

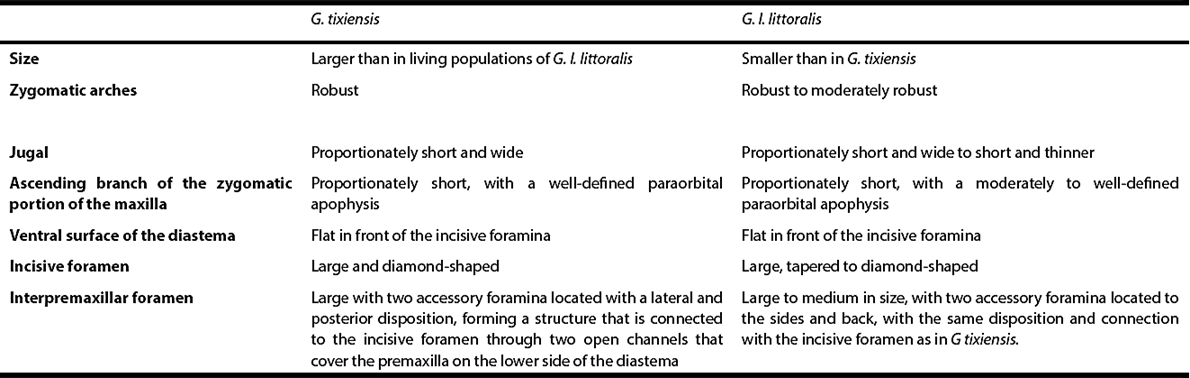

The states for morphological traits originally referred to as diagnostic for G. tixiensis were also observed in living specimens of G. leucoblephara. The morphological variability recorded in different qualitative features of the fossil taxon is well within the variability documented for the living populations of G. leucoblephara, but especially of G. l. littoralis (for a summary see Table 3).

Table 3 Diagnostic traits of Galea tixiensis (from Quintana, 2001) and expression of these same traits in a sample of 20 adult specimens of G. leucoblephara littoralis (for further details see Appendix 1).

Discussion

The most striking feature of G. tixiensis relative to other species in the same genus is its larger overall size (Quintana 2001:404). However, a size-adjusted PCA indicates that, in terms of figure, the G. tixiensis holotype does not differ from other individuals referred to as G. leucoblephara. This is not a minor issue, as certain quantitative traits are among the phenotypic variables most frequently associated with physiological or environmental changes (e. g., Maestri et al. 2016). Also, some differences might be magnified by the different sample sizes considered by previous authors. For example, for a set of 35 individuals of G. leucoblephara, Quintana (2001) reported a higher mean upper alveolar toothrow length of 11.77 mm, with a range between 10.4 to11.7 mm (n = 35; note the contradiction between the mean and maximum values recorded), while for the same species, with a sample three times larger (n = 110), we recorded an average of 11.82 mm and a range of 10.1 to 15.54 mm (n = 110). This evidences that although the mean value remains clearly lower for G. leucoblephara, the range of measurements for this species covers completely the range reported for G. tixiensis (mean = 13.18 mm; 12.2-15.1 mm range; n = 107).

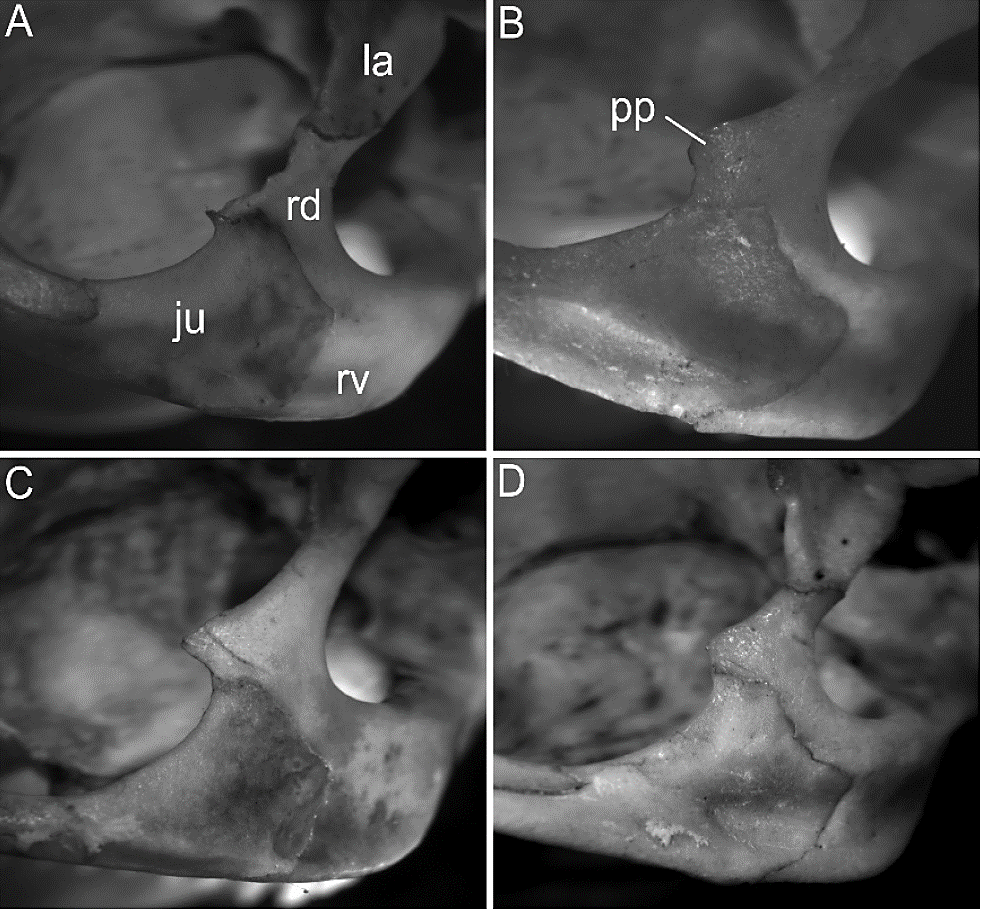

Our review of extensive series of specimens indicates that none of the qualitative traits supposedly diagnostics of G. tixiensis, nor the combination of them, is unique to this taxon. For example, the morphology of the zygomatic arch and the diastema and its associated foramina does not differ significantly from the one observed in living specimens of G. l. littoralis (cf. Figures 3 and 4; Table 3). In this subspecies, the shape of the incisive foramen varies between tapered and diamond-shaped, together with the presence of a conspicuous interpremaxillar foramen, accompanied by accessory foramina with a lateral and posterior arrangement, in a disposition similar to that reported for G. tixiensis (Figure 3). This contradicts what has been pointed out by Quintana (2001:402 to 404), who indicated that the diamond shape of the incisive foramen was exclusive to the fossil species and that the accessory foramina were not present in other species, nor did this displayed the overall disposition as G. tixiensis. Also, the robustness of the zygomatic arch, as well as the development of the paraorbital apophysis on the ascending branch of the zygomatic portion of the maxilla and the size of the jugal were relatively variable in samples of the living specimens, with some individuals (e. g., MACN-Ma 13335; cf. Figure 4B) displaying a disposition similar to the one observed in G. tixiensis (cf. Quintana 2001; Fig. 3A). Other traits (e. g., shape of the mesopterygoid fossa, shape of the nasolacrimal foramen, appearance of the tympanic bulla, morphology of the mandibular ramus and molars) did not show major differences between G. tixiensis and G. leucoblephara (cf. Quintana 2001; this work). For all the above mentioned, we consider that there is no qualitative morphological evidence to suggest that G. tixiensis is a different species from G. leucoblephara.

Figure 3 Individual variation in the morphology of incisive foramina and associated structures in specimens of Galea leucoblephara littoralis (from left to right: MACN-Ma 13226, 22607, 16405, 13664). Abbreviations: fa = lateral accessory foramina; fip = interpremaxillar foramen.

Figure 4 Individual variation in the morphology of the orbit in specimens of Galea leucoblephara littoralis: A) MACN-Ma 16405; B) MACN-Ma 13335; C) MACN-Ma 22607; D) MACN-Ma 13226. Abbreviations: ju = jugal; = lacrimal; pp = paraorbital apophyses; rd/rv = dorsal/ventral root of the zygomatic portion of the maxilla.

For Quintana (2001), G. tixiensis became extinct toward the 18th century, in accordance with the earliest records of exotic wildlife in the southeast of the Province of Buenos Aires, during a period of cold and dry climate referred to as the Little Ice Age. If his hypothesis is correct, G. tixien-sis would have been replaced in those same ecosystems by G. l. littoralis, the species currently recorded in the south of the pampas region (Galliari et al. 1991). In other words, the colonization of G. l. littoralis would have occurred in the last 200 years after the extinction of G. tixiensis, since there are no references of both species coexisting in sympatry in any of the sites studied by Quintana (2001; see also Quintana, 2016a, 2016b). This hypothesis is hardly parsimonious, especially in view of the morphological results discussed above. It is more likely that G. leucoblephara had experienced changes in size throughout the Holocene, a phenomenon that is well documented for mammals of the Northern Hemisphere (Martin and Barnosky 1993). In fact, the record of Holocene mammals of larger sizes than their living counterparts has already been mentioned for hilly and interhilly areas of Buenos Aires. A number of authors have highlighted the findings in various archaeological and fossils sites, of specimens of the rodent Dolichotis patagonum (e. g., Lobería; Tonni 1985) and the xenarthran Zaedyus pichiy (e. g., La Toma, Fortín Necochea, Laguna del Trompa, San Martin; see Vizcaino et al. 1993) based on skeletal remains of larger size vs living specimens. A similar finding has been described for the cervid Ozotocerus bezoarticus and the sig-modontine rodent Holochilus vulpinus in several sites in the hilly area of Cordoba, central Argentina, for the same period of time (Teta et al. 2005; Medina and Merino 2012).

The climatic conditions for the largest part of the Holocene in the Pampean region were colder and drier than the current climate (cf. Tonni et al. 1999). In this context, it would not be unlikely that some mammal lineages likely developed phenotypic and physiological responses consistent with this scenario, including the variation in size, but not necessarily implying speciation events.

nova página do texto(beta)

nova página do texto(beta)