Introduction

The plant locally known as ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens: Fouquieriaceae) is a shrub endemic to arid regions of southwestern United States and northern Mexico (from northern Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila and Durango; Walkowiak et al. 1990; Zamudio 1995); it reaches a height of 2 to 6 m and shows simple thorny branches from the base. It has no leaves for most of the year; these emerge suddenly after the first rain (March) (Zamudio 1995). Inflorescences are terminal (Reyes-Carmona and García-Gil 1982; Bowers 2006) and emerge simultaneously in all plants in early spring (March) and last a little more than a month. Some studies have determined that plant size is positively related with the number of inflorescences (Díaz et al. 2015), although not necessarily with a larger number of flowers (Bowers 2006). The bright red flowers are small (2.5 cm, Reyes-Carmona and García-Gil 1982; Bowers 2006) and, due to their tubular shape, are visited by insects and birds, in addition to being consumed by some birds (i. e., Icterus sp.) and mammals (i. e., Odocoileus hemionus).

Since ocotillo is a food resource for many animals in the dry season, including the mule deer (O. hemionus), the inflorescences produced in each plant during March were quantified, as well as the inflorescences potentially available for O. hemionus. Since the mule deer is a highly selective herbivore browser (Short 1981), biomass availability (fresh weight) and nutrient content of F. splendens inflorescences were also estimated.

Materials and Methods

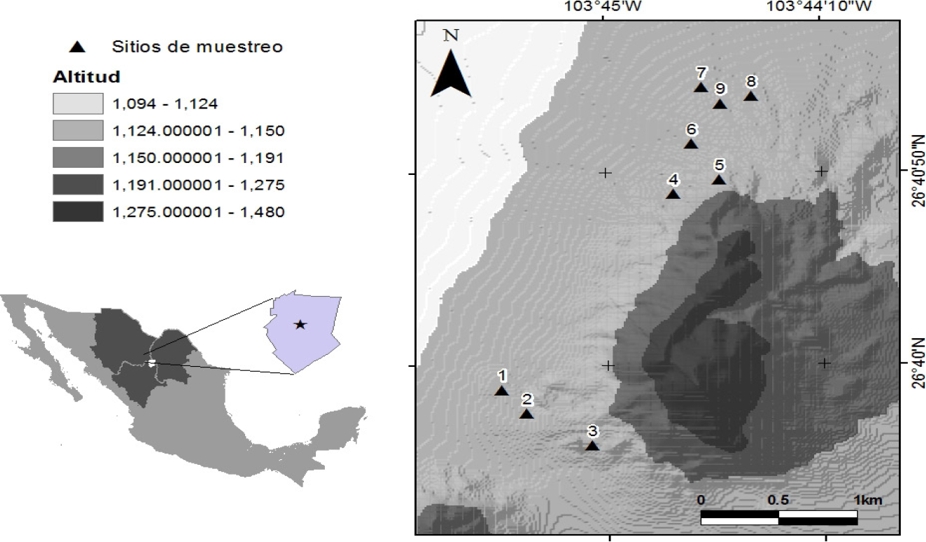

The work was carried out in March 2012 in the foothills and surroundings of Cerro San Ignacio, Mapimi Biosphere Reserve (-103° 45’ and -103° 43’ W, 26º 40’ and 26° 39’ N). The local climate is dry and semi-warm (mean annual temperature = 20.8 ºC) with summer rainfall (mean annual precipitation = 264 mm). The highest abundance of F. splendens occurs in xerophilous scrubland (CONANP 2006). The sampling of ocotillo plants was carried out using the nearest-neighbor method (Clark and Evans 1954). First, an individual was chosen at random, following with the nearest individual of the same species, and so on until 30 individuals were measured. Nine replicas of the sampling were conducted on the foothills of Cerro San Ignacio (Figure 1). The following variables were measured from each plant: 1) distance to the nearest individual, that indicates the species density, 2) shrub height, 3) number of branches, 4) largest diameter, 5) smallest diameter, 6) total number of inflorescences, and 7) number of inflorescences available for the deer (to a maximum height of 1.80 m, considering the height reached by an adult animal standing on its hind legs (see Figure 2). Inflorescences were collected from other ocotillo plants selected at random to estimate the average fresh weight, which was multiplied by the total number of inflorescences estimated in the first sampling. In addition, the number of available inflorescences were counted to estimate total productivity, and from the inflorescences collected the nutrient content was determined through proximal chemical analyses in the laboratory of Food Chemical Analysis at the College of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, UNAM.

Figure 1 Image of the Cerro San Ignacio, Mapimí Biosphere Reserve, Durango, showing the sampling sites.

The measures of central tendency (mean and standard deviation) were obtained for each of the seven variables. To determine which variables affect the number of inflorescences and their productivity, a Pearson correlation matrix was elaborated. All analyzes were performed with the program PAST (Hammer et al. 2009). The significance level considered was 0.05.

Results

The seven structural variables were measured in 270 ocotillo plants (30 plants with nine replicates each). The average plant height for the nine replicates was 2.49 m (± 0.17) and the smallest diameter was 2.34 m (± 0.24). The number of inflorescences per individual plant was 29.45 (± 8.23) and the number of inflorescences available at 1.8 m height was 12.24 (± 3.08) per plant. The availability of inflorescences for the mule deer is 41.57 % (3.306) of the total for 270 plants (n = 7951).

The number of branches per plant is positively correlated with the number of inflorescences available (P = 0.007) and total inflorescences (P = 0.0119); also, the available inflorescences are correlated with the largest diameter (P = 0.004) and the smallest diameter (P = 0.001); and the total inflorescences with the available inflorescences (P = 0.0004; Table 1).

Table 1 Linear correlation matrix for the seven variables measured in Fouquieria splendens. Below the diagonal are the correlation coefficient; above, the significance.

| No. Branches | Height (m) | Largest diameter | Smallest diameter | Available inflorescences | Total inflorescences | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Branches | - | 0.169 | 0.059 | 0.005 | 0.007 | 0.0119 |

| Height (m) | 0.501 | - | 0.264 | 0.224 | 0.234 | 0.2560 |

| Largest diameter | 0.649 | 0.417 | - | 0.001 | 0.004 | 0.0004 |

| Smallest diameter | 0.836 | 0.450 | 0.946 | - | 0.001 | 7.77E-05 |

| Available inflorescences | 0.819 | 0.442 | 0.841 | 0.894 | - | 0.0004 |

| Total inflorescences | 0.786 | 0.423 | 0.922 | 0.952 | 0.921 | - |

The average inflorescence fresh weight was 74.8 g (± 20.5) and the proximal chemical analysis shows that the digestible nutrients account for 85.4 % dry basis, with a metabolizable energy of 3,085.98 kcal/kg; 11.5 % crude protein and 66.9 % carbohydrate (Table 2).

Table 2 Percentage nutrients and energy (dry and wet basis) by Proximal Chemical Analysis of ocotillo inflorescences.

| Wet basis (%) | Dry Basis (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Dry matter | 65.55 | 100.00 |

| Moisture | 34.45 | 0 |

| Crude protein | 7.51 | 11.46 |

| Lipids | 3.55 | 5.41 |

| Ash content | 3.31 | 5.05 |

| Crude fiber | 7.30 | 11.13 |

| Nitrogen-free extract | 43.88 | 66.94 |

| Total digestible nutrients | 55.96 | 85.37 |

| Digestible energy (kcal/kg) | 2,467.16 | 3,763.79 |

| Metabolizable energy (kcal/kg) | 2,022.86 | 3,085.98 |

Discussion and Conclusions

The structural variables of the plant, such as the number of branches and the diameter, determined the number of inflorescences in ocotillo, unlike the work of Diaz et al. (2015), who point out that plant size is positively related to the number of inflorescences. The results of this study show that ocotillo flowers are readily available for the mule deer in the critical dry season, with around 1.5 kg of available inflorescences per plant, which are characterized by high protein, energy and digestibility. However, the productivity of inflorescences varies spatially due to plant density (depends on the distance between individuals), which varied between sites more than individual productivity.

The mule deer is a highly selective browser, so that plants with high nutritional value are very important, considering their availability, as ocotillo inflorescences (Short 1981) in this case. Compared to other plants foraged by the mule deer in the same area (RBM), protein and lipid levels are 4.0 % and 10.0 %, respectively, in Euphorbia antisyphilitica (candelilla); Jatropha dioica (sangre de drago) supplies 8.8 % protein and 11.0 % lipids; Opuntia rastrera (prickly pear), 4.4 % protein and 5.0 % lipids; Agave asperrima (agave), 9.0 % protein and 5.0 % lipids (Cossío Bayugar 2014). If we take into account that the deer requires at least 7.0 % crude protein to survive, 9.5 % to attain moderate growth and 14.0 to 20.0 % for an optimum development (Halls 1984; Brown 1994; Miller and Marchinton 1995; Villarreal 2000), ocotillo shows values of protein and other nutrients that can contribute significantly to the diet of the mule deer in critical times. Although the number of inflorescences consumed and its proportion relative to the total diet of the mule deer in the dry season remain unknown, ocotillo inflorescences can be considered as an important food resource for its nutrient concentration relative to other plants, and also for its high availability in the dry season precisely.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)