Introduction

The Neotropical otter or “perro de agua” Lontra longicaudis is a carnivore of the Mustelidae family. As well as its congeners, L. longicaudis is an opportunistic predator that consumes fish (its main diet component), crustaceans, mollusks, birds, reptiles, small mammals and insects (Helder and Ker de Andrade 1997). It ranges from northern Mexico to northern Argentina in the province of Buenos Aires, with altitudinal distribution between 0 and 3,885 m above the sea level (Emmons and Feer 1997; Castro-Revelo and Zapata-Ríos 2001). However, its altitudinal range of preference is between 300 to 1,700 m (Larivière 1999). L. longicaudis is the most common otter in Colombia, where it inhabits the evergreen forest, rain forest and savannas associated to fresh water ecosystems (Larivière 1999; Calderón-Capote et al. 2015). The Neotropical otter has low tolerance to transformed habitats. However, Trujillo and Arcila (2006) reported the presence of L. longicaudis on rivers with highly anthropic disturbances. Most of the published studies in Colombia have been carried out in the trans-Andean region. The most common topics for these studies include habitat use and diet (Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero 2010a, b), trophic ecology of some populations that occur at Cauca and Quindio departments (Restrepo and Botero-Botero 2012), and range expansion at Putumayo (Noguera-Urbano and Montenegro-Muñoz 2011). Also, several records of L. longicaudis have been mentioned in regional and national mammal lists, which are based on personal observations, museum specimens records and literature compilations (see, Ferrer-Pérez et al. 2009; Ramírez-Chaves and Noguera-Urbano 2010; Solari et al. 2013). Nevertheless, large areas of Colombia are lacking intensive sampling, especially the Andean highlands, and particularly the Paramos of the Cordillera Oriental. Therefore, L. longicaudis is considered a research priority due the poor information about its presence and abundance in the country (González-Maya et al. 2011). The aim of this paper is to gain insights on the altitudinal distribution of L. longicaudis in the Colombian Paramos of Boyacá, Colombia.

Materials and Methods

Fieldwork was carried out in the municipalities of Chinavita, Garagoa and Viracachá, department of Boyacá on the eastern slopes of the Cordillera Oriental. The sampling stations were located in Andean forest, Paramo and the ecotone between these ecosystems. Surveys were conducted between November 18th to December 7th of 2015, using 12 camera-traps (four ScoutGuard SG550V and eight Bushnell 8MP Trophy Cam Standard). Each camera-trap was considered as a track sampling unit. The cameras were placed at 50 cm of the floor, near places with animal trails, traces, feeding places, refuges or ecotones between the Paramo and the Andean forest. The sampling effort was of 4,320 h of camera-recording, and each sampling station was baited at the first day of the survey during eight days with 160 g of sardines. Additionally, for comparative purposes, preserved specimens housed in Colección de Mamíferos Alberto Cadena García, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales of Universidad Nacional de Colombia (ICN) were examined. Also, historical records of L. longicaudis in scientific publications and museums were consulted, with emphasis on record sightings above 2,000 m.

Results

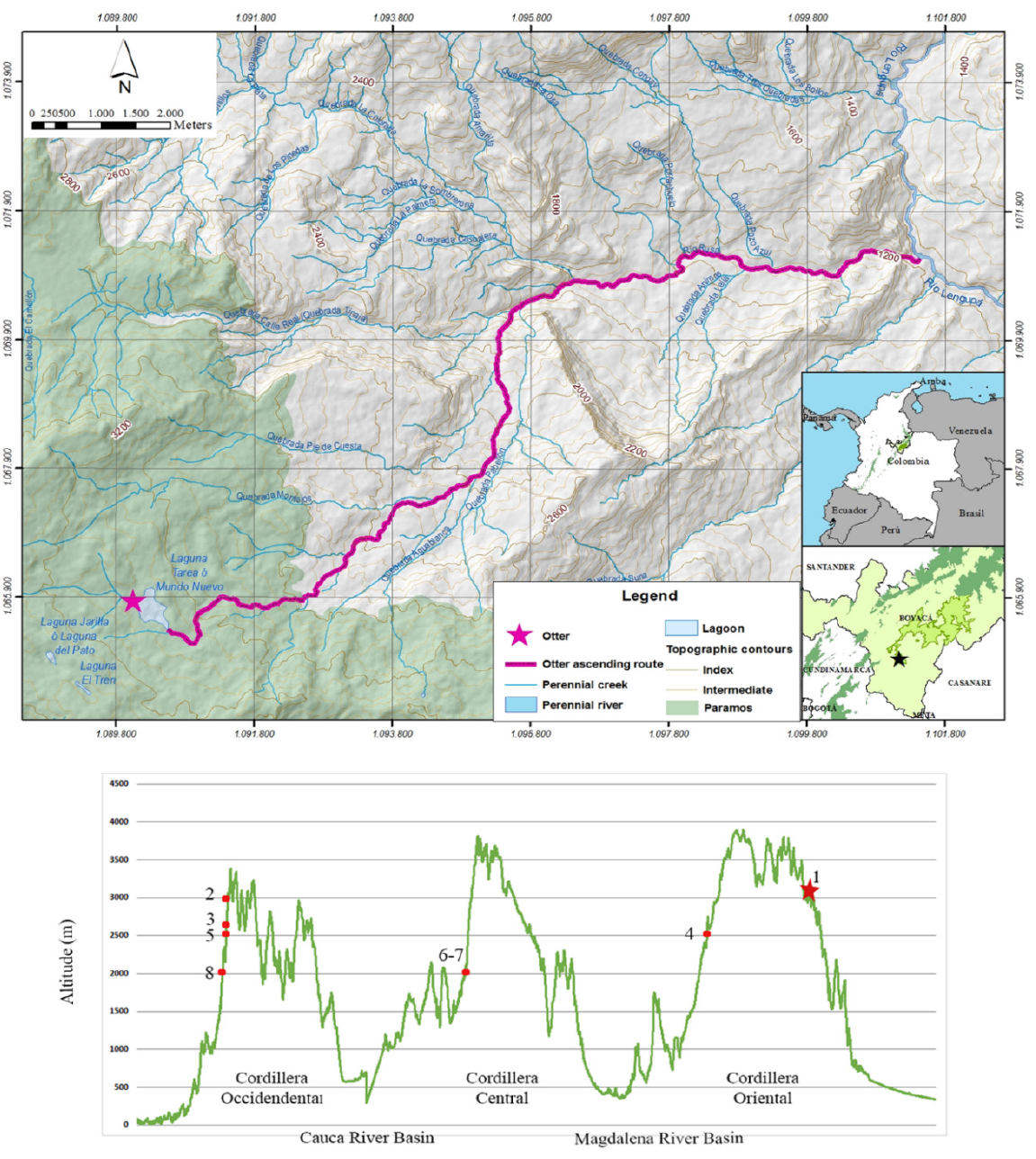

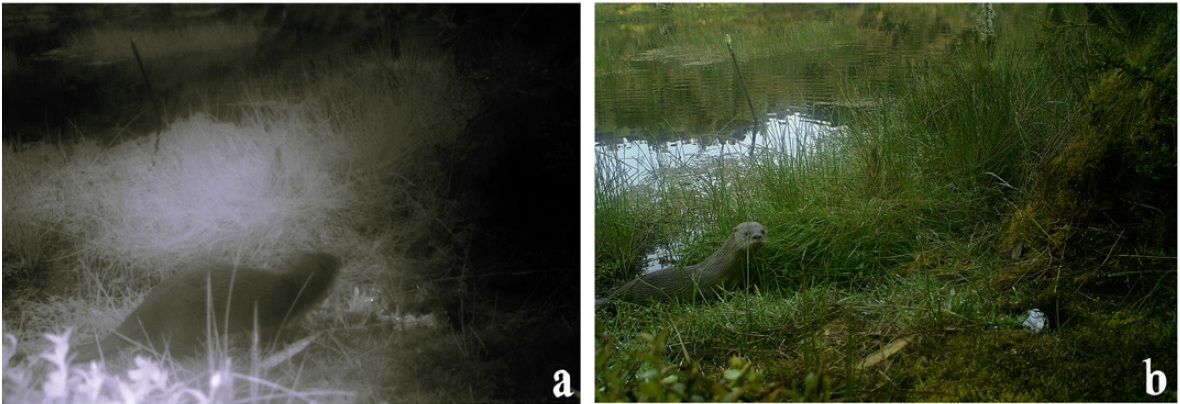

A total of 275 images of wildlife were recorded, of which four pictures were of L. longicaudis. All records came from the station Mundo Nuevo Lagoon at the municipality of Chinavita (3,110 m; Figure 1). These camera traps were placed over the edge of the Mundo Nuevo lagoon which is surrounded by shrubbery vegetation and frailejones (Espeletia spp.). The first and second images were taken on November 27 at 20:03 and 20:17 respectively. These pictures show one specimen of L. longicaudis approaching the bait. The third and fourth images were taken on November 28 at 06:57 and 09:03 respectively. In these occasions the pictures show one specimen approaching the camera-trap. Features such as sex and age cannot be distinguished from the individuals photographed (Figure 2). These images were taken in areas where otter scats and fish remains were found.

Figure 1 Record of Neotropical otter at Chinavita Municipality that extends their altitudinal range. Possible otter ascending route with the altitudinal profile of records above 2,000 m in Colombia based on our records and those from the literature and preserved specimens. 1. This study; 2. Rojas-díaz et al. 2012; 3. Ramírez-Chaves and Noguera-Urbano 2010; 4. FMNH 146397; 5. FMNH 8848; 6. Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero 2010a ; 7. Mayor-Victoria and Botero-Botero 2010 b; 8. Corantioquia / 8110002317-09. Cordillera Occidental cut west to east over south of Cauca department with 135 degrees. Cordillera Central cut west to east over Valle del Cauca through south Quindío Department, with 138 degrees. Cordillera Oriental cut west to east over Tolima department to North of Meta department.

Figure 2 Records of L. longicaudis from municipality of Chinavita at 3,110 m a) Third record at 06:54, on November 28. b) Fourth record at 09:03, on November 28.

Rojas-Diaz et al. (2012) reported the presence of L. longicaudis at 3,000 m at both slopes of the Cordillera Occidental. However, that record was not confirmed due that it lacks the specific locality and collection number. Only seven specimen sightings at 2,000 m or above were found on the literature and museum records (Table 1). The highest altitude reported was 2,700 m (Ramírez-Chaves and Noguera-Urbano 2010), which confirms that our record represents an altitudinal range expansion of L. longicaudis as well as the maximum altitude recorded for the species in Colombia.

Discussion

The niche partitioning theory states that the presence of carnivores is associated directly with their prey abundance and presence (Sunquist and Sunquist 1989). The altitudinal range expansion of L. longicaudis from Mamapacha’s Paramo at 3,110 m might supports this hypothesis. Commonly, this species inhabits riverine ecosystems between 0 to 1,700 m that provide a wide range of food availability (Larivière 1999). However, Guerrero-Flores et al. (2013) indicate that L. longicaudis is an opportunistic predator with a broad food spectrum that allows it to move outside of its preference range when abundant food supply is available. Therefore, the altitudinal range expansion of L. longicaudis can be a consequence of an abundant food supply, provided by the Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), an introduced species that inhabits the high mountain lagoons at Mamapacha Paramos.

The rainbow trout was introduced on Boyacá high mountain lagoons about 90 years ago with the goal to use them in artisanal and sport fisheries (Parrado-Sanabria 2012). As a result, many rainbow trout fisheries were established throughout the region of Mundo Nuevo village. Due to the generalist diet and predator characteristics of Rainbow trout, it became the dominant and most abundant species of fish on the high mountain lagoons (Martín-Torrijos et al. 2016). Therefore, the rainbow trout is an abundant food supply that might encourage otters to move from lowlands to highlands. This pattern agrees with reports by Monroy-Vilchis and Mundo (2009), and Guerrero-Flores et al. (2013) who found that colonization of high mountain ecosystem in Mexico by L. longicaudis is related to the invasive species abundance, which in some cases, represents almost 100 % of the otter diet. Likewise, Castro-Revelo and Zapata-Ríos (2001) have reported L. longicaudis at 3,885 m in Ecuador, pointing out that they found fish remains associated to the diet of the otter, however, they not specified whether they belong to native or introduced species. Whereby, more diet preference and prey abundance studies are needed in order to verify whether the altitudinal range increase of L. longicaudis is due to this food availability provided by the trout (Briones-Salas et al. 2013; Guerrero-Flores et al. 2013).

Additionally, based on landscape cover and the drainage connectivity. We hypothesize the possible ascending route used by L. longicaudis to reach the Mundo Nuevo Lagoon (Figure 1). First, the possible population source might have been located at Batatá dam (1,042 m). Second, the ascending route might have started from Batatá dam, through La Rusa River, through Canelo creek until reaching to Mundo Nuevo Lagoon. Moreover, a robust sampling effort must be encouraged to understand the size and distribution of L. longicaudis populations in the rivers and creeks of the municipalities of Chinavita, Garagoa and Viracachá.

Finally, the Mundo Nuevo Lagoon local farmers have noticed the presence of L. longicaudis for decades, following the introduction of rainbow trout and the establishment of trout fisheries in the area. Also, they suggest that the otter population might be of about five to six individuals. But the actual number of otters that inhabits the area is unknown. The highland population of L. longicaudis might be threatened by local farmers because they are in direct competition for the trout, as prey for the otters and food supply or income to the farmers. Hence, Neotropical otters are considered as a pest by local fishermen, some otters have been chased and killed to diminish the otter population.

This note presents the highest altitude record of L. longicaudis in Colombia, contributing to the knowledge of neotropical otter distribution in Boyacá Paramos. Likewise, our observation suggests that altitudinal range expansion record might be associated with the prey availability that represents the introduction of Rainbow trout and the development of a trout fishery at the Paramos lagoons. However, more diet studies on the otters at Mundo Nuevo Lagoon are required to verify this hypothesis. On the other hand, conservation strategies together with environmental education are needed in order to reduce human-otter conflict.

nueva página del texto (beta)

nueva página del texto (beta)