Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Intervención (México DF)

versão impressa ISSN 2007-249X

Intervención (Méx. DF) vol.14 no.27 México Jan./Jun. 2023 Epub 30-Jan-2024

https://doi.org/10.30763/intervencion.278.v1n27.57.2023

Research Articles

The Cultural Value of Immovable Heritage in Peru for the Renewal of Cultural Tourism. The Case of the Historic Center of Lima

1 Universidad Femenina del Sagrado Corazón (Unifé), Perú. analebrun@hotmail.com

2Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), México. hgeovannini@gmail.com

The Historic Center of Lima possesses an irreplaceable immovable heritage, which has suffered constant deterioration over the years. To determine its value for the renewal of cultural tourism, the associated cultural values and outstanding universal value (OUV) were examined through a mixed investigation that included documentary analysis, and a structured record and survey file. It was identified that the recognition of the former and the latter by the actors involved constitutes a relevant element for tourism renewal, allowing the enhancement and conservation of the historic center.

Keywords: Historic Center of Lima; cultural tourism; outstanding universal value; cultural value

El Centro Histórico de Lima cuenta con bienes inmuebles invaluables que a lo largo de los años han sufrido deterioro constante. Con el fin de determinar para la renovación del turismo cultural el valor del patrimonio inmueble, se examinaron, por medio de una investigación mixta que incluyó el análisis documental y una ficha estructurada de registro y encuestas, los valores culturales y el valor universal excepcional (VUE) asociados. Se identificó que el reconocimiento de aquéllos y éste por parte de los actores involucrados constituye un elemento relevante para la renovación turística, permitiendo la puesta en valor y conservación del centro histórico.

Palabras clave: Centro Histórico de Lima; turismo cultural; valor universal excepcional; valor cultural

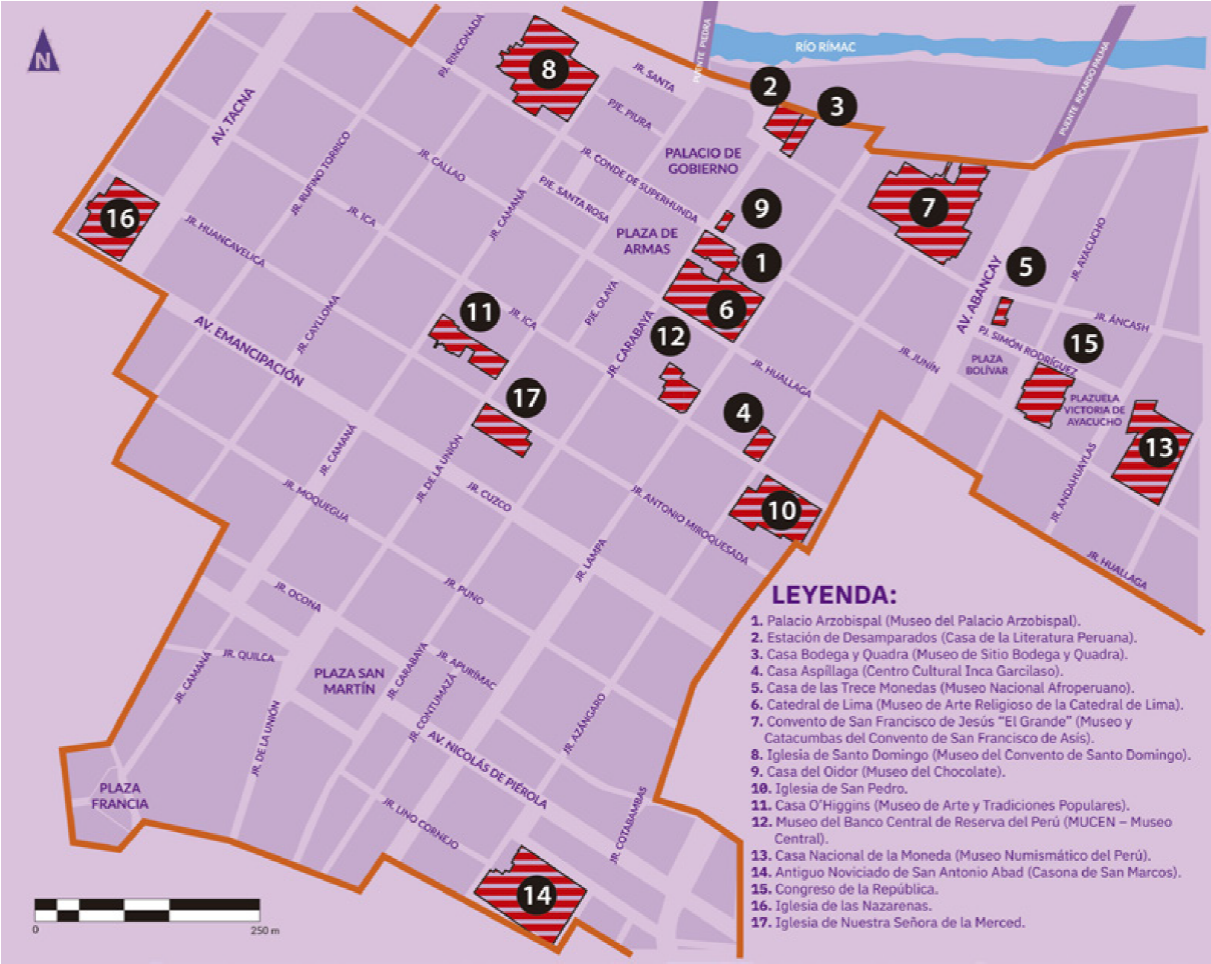

On December 13, 1991, following the provisions of the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, 1972, p. 4), the Historic Center of Lima was enrolled by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) as World Heritage, because it is an excellent witness of the architectural and urban development of a Latin American colonial city of great political, economic, and cultural importance (International Council on Monuments and Sites [ICOMOS], 1991, p. 1). It has an extension of 259.36 ha, with 766.7 ha corresponding to the area of the buffer zone (Figure 1).

(Source: Municipalidad Metropolitana de Lima [MML], 2014, p. 28)

Figure 1 Plan of the Historic Center of Lima and World Heritage area adapted from the Metropolitan Municipality of Lima, Municipal Program for the Recovery of the Historic Center of Lima-Prolima and Lima City for All.

The area of the Historic Center of Lima has irreplaceable immovable heritage within its boundaries, such as houses, colonial churches, and colonial buildings, both republican and modern. Unfortunately, over the years it has presented a series of problems related to the deterioration of heritage buildings, due to the lack of both maintenance and prevention, and conservation of the infrastructure by owners, tenants, businessmen, and authorities, particularly the Municipality and the Ministry of Culture (Negro, 2019, pp. 170-171; Rodríguez, 2019, pp. 313-315).

Many efforts have been made to stop the deterioration of the immovable heritage (Municipalidad Metropolitana de Lima [MML], 2019, p. 409), but the actions for the conservation and restoration of the Historic Center, besides being insufficient, have not involved experts and the local population. This is why this RESEARCH ARTICLE examines the perspective of some of the actors involved regarding cultural values and the outstanding universal value (OUV) of the heritage properties of that polygon, so that their splendor and magnificence are recovered for their preservation, conservation, enhancement, and new social and cultural use.

Background

Lima, also called Ciudad de los Reyes (City of the Kings), capital of Peru, located on the central coast of the country in the Pachacamac valley, and crossed by the Rimac River, was founded on January 18, 1535, with an original layout in the form of a rectangle of 9 by 13 blocks, called the Pizarro checkerboard (Gunther & Lohman, 1992, p. 64). By the 19th century, the Cercado de Lima (Walled Lima), which includes the Historic Center, was already the first district created in the city, which since then has grown in a fragmented manner, and constitutes an urban palimpsest product of different stages of its historical events.

The criteria of exceptionality, integrity, and authenticity were considered for the declaration of the Historic Center as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988-although its area was extended in 1991 (UNESCO, 2019, p. 1).

According to what was stated by the above-mentioned municipality, the immovable heritage of Lima is made up of 649 buildings declared as monuments and 1 278 of monumental value, as well as 62 public spaces declared as urban-monumental environments. Regarding its state of conservation, 45% is fair, 21% bad and very bad, and 27% good and very good (MML, 2019).

Cultural heritage of the historical center of lima and its problems

With the evolution of the concept of cultural heritage throughout history, today the cultural value of immovable heritage is understood by citizens as the heritage where the collective, symbolic, and spiritual memory of the community is embodied, with the commitment to its preservation, which constitutes a pillar of identity, social cohesion, and economic development: “cultural heritage is both a product and a process that provides societies with a wealth of resources that are inherited from the past, created in the present and transmitted to future generations for their benefit”1 (UNESCO, 2014, p. 132).

The Historic Center of Lima has a population of 125 265 inhabitants (MML, 2019, p. 150). The problem of its deterioration has increased because of climate change, pollution, the formation of slums of historic buildings, depopulation, the commercial exploitation of old houses, and the earthquakes registered in the 20th century (Dammert, 2018, p. 54; Shimabukuro, 2015, p. 11). The Municipality (2019) recognizes that the foregoing is also due to poor, disjointed coordination, as well as a lack of knowledge of the concept and importance of the OUV by the sub-managements linked to culture and tourism and the non-existence of multidisciplinary teams that work to safeguard heritage.

In this line, and with the purpose of suggesting alternatives to address this complex problem, the question arises about how the appreciation and knowledge of the cultural values associated with immovable heritage are present and would allow the renewal of cultural tourism in the Historic Center as World Heritage. Thus, the object will be to analyze those values among some of the actors involved and establish guidelines for renewal from a cultural tourism approach.

The outstanding universal value (OUV) and cultural values

The concept of OUV has been used to assess and recognize the significance of a heritage site as having “such extraordinary cultural and/or natural significance that it transcends national borders and is of importance to present and future generations of all mankind. Therefore, the permanent protection of this heritage is of supreme importance for the international community as a whole” (UNESCO, 2008, p. 16). In other Latin American heritage historical centers, the importance of recognizing the OUV for heritage appreciation, and improvement in the tourist experience has already been underlined (Ruiz & Pérez, 2021, p. 45; Sizzo, 2013, p. 130).

In addition to the OUV, knowledge of cultural values (“products of the human mind, based on parameters found in relevant socio-cultural and physical contexts” [Jokilehto, 2017, p. 26]) is necessary for the sense that “intangible heritage has the potential to affect the tangible realm” (Vit, 2017, p. 255). The inherent values of immovable heritage change over time and generate different ways of relating to it. In order to define them in the context of the Peruvian historical immovable heritage, the Ministry of Culture (2017, pp. 13-21) prepared a document for their identification and declaration that has served as a guide, which includes definitions by authors such as Alois Riegl (1987), Joseph Ballart (1997), Françoise Choay (2007), Instituto Nacional de Cultura (National Institute of Culture) (INC, 2007), Díaz (2016), and Mayordomo & Hermosilla (2019), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Cultural values and their definitions

| VALUES | DEFINITIONS |

|---|---|

| Historical value | When the immovable building constitutes a relevant testimony of an event or process of the past, whether in the political, military, economic, social, or artistic field, whether in the technological or urban field, or due to the fact that the property represents a certain evolutionary stage of the country’s architecture as a physical testimony that remains until today; due to its foundation, the development of the city or town, antiquity, historical event, testimony or evidence, significance, role or function in its physical, political, social, and economic context (Mincul, 2017, p. 20). An immovable heritage building with historical value is an essential component in the construction of the memory of a community (Mincul, 2017, p. 20). |

| Architectural value | When the property stands out for the attributes of its relevant architectural representativeness: due to its uniqueness, its aesthetic, architectural or urban quality. This considers styles, facades, details, construction technology, materials, ornamentation, and aesthetics (Mincul, 2017, p. 20). |

| Social value | This is manifested in the sense of belonging to a human group and its relationship with the immovable heritage subject of evaluation, reflected in the collective references of memory and identity: relationship with immaterial cultural manifestations, religion, customs, traditions, and meaning of buildings with patrimonial value -commemorative and public spaces. Consequently, the immovable building has a symbolic value for a certain human group due to its close relationship between the property and the community (Mincul, 2017, p. 21). |

| Technological value | For its contribution to the field of construction technology, use of materials, and construction systems typical of a certain place or time. This value is considered based on the correspondence of the material with the time of construction and its technological contribution, which enabled the construction of the building and gave it a unique character that distinguishes it from buildings of other times (Mincul, 2017, p. 21). |

| Aesthetic value | When attributes of artistic or design quality are recognized in the building, which reflect an idea of a balanced composition accompanied by construction technology in accordance with the design; this value is related to the appreciation of the physical characteristics of the property (Mincul, 2017, p. 21). |

| Artistic value | It refers to the architectural elements that contain ornamental, sculptural, or pictorial representations relevant in their design and materiality, which are part of the immovable heritage building (Mincul, 2017, p. 21). |

| Antiquity value | It is based on the opposition to the present manifested in the perception of the traces of deterioration caused by nature in its slow and irrepressible work. This disintegration of the human work causes an aesthetic and emotional effect on the people. It is considered that there is a continuous creation in which what is modern today will become an ancient monument (Riegl, 1987, p. 49). |

| Symbolic and Significant Value | It is the consideration of objects from the past that are in some way vehicles of the relationship between the people who produced or used them and their current recipients (Ballart, 1997, p. 82). |

| Scientific Value | A site’s scientific value or research potential depends on the importance of the information that exists, its rarity, its quality, its representativeness, and the degree to which the site can provide additional data of great substance (Riegl, 1987, p.52). |

| Use value | Instrumental value: the use value and practical purpose of the monument: therefore, it does not apply to archaeological sites or ruins (Riegl, 1987, p. 73). It is the utilitarian dimension of the historical object (Ballart, 1997, p. 59). |

| Authenticity | Authenticity refers to the site’s ability to faithfully convey its historical significance. It is a necessary condition to support the outstanding universal value, OUV (Instituto Nacional de Cultura [National Institute of Culture], 2007, p. 394). It includes the conservation and maintenance of the original characteristics and values of the work and its surroundings, even if there are subsequent interventions. The variables refer to the traditional image, techniques, and morphology of the building, and also consider the processes that affect its physical qualities and its original location (Mayordomo & Hermosilla, 2019). |

| Function | Activity that takes place within an immovable heritage building in its physical, political, social, and economic context. Depending on the type of cultural asset, there are qualities that can be modified without affecting its cultural values (Díaz, 2016, p. 45). |

(Plan: Ana María Lebrún, 2022; sources: Díaz, 2016; Mincul, 2017; INC, 2007 and Mayordomo & Hermosilla, 2019).

Cultural tourism and immovable heritage

The Organización Mundial del Turismo (OMT, in Spanish, World Tourism Organization, UNWTO) defines cultural tourism as “a type of tourist activity in which the essential motivation of the visitor is to learn, discover, experience, and consume the cultural, tangible, and intangible attractions/products of a tourist destination” (OMT, 2019, p. 31).

Rico establishes that from the tourism perspective there is a close relationship between cultural heritage and society, in which the social and recreational use of heritage elements comes into play, where “the visitor acquires a fundamental role” (Rico, 2014, p. 561). Immo vable heritage is an unavoidable “input” for tourism, so it is essential that it be protected, preserved, and conserved through a plan which integrates social, cultural, tourism, economic, and environmental policies. The heritage aspects of a city have a privileged place, as stated by Vera (2015, p. 100) in tourism strategies as a potential booster of the economy, in which tangible and intangible heritage has a specific function, oriented towards cultural consumption.

Likewise, Rico and Baños indicate that for the renewal processes of tourist destinations to be carried out, it is necessary to emphasize that cultural heritage is a relevant element of social value that diversifies the tourist offer, including its own differentiating features (Rico & Baños, 2016, p. 316). Even more, Villalba states that immovable heritage has become a special and attractive tourist destination on its own (2016, pp. 345-346).

Methodology

As a first step, a building selection was carried out to interpret cultural values in the context of a renewal of cultural tourism in the Historic Center of Lima. Although there are 72 that are a heritage (museums, mansions and churches) considered tourists (MML, 2019, p. 276), to carry out a comparative analysis in the same terms, their attributes, location, and access were prioritized according to eight criteria: having been declared Cultural Heritage of the Nation; being located within the perimeter of the area declared as World Heritage by UNESCO; having social and/or cultural, and/or commercial, and/or religious use (García, 1999, p. 33); being open to the public; functioning as publicly owned premises; being associated with a historical event or with a historical figure registered in archives or publications; receiving national and international tourists, and having sufficient historical information on the heritage property.

After the selection, a detailed documentary analysis of the properties was carried out, which made it possible to collect data from the primary and secondary written sources available in both public and private libraries and archives. With this analysis, the quality of the historical foundations of the study was guaranteed, through a systematic, integral and sequential process of collection, selection, classification, analysis, and evaluation of the content of the existing material.

The next step consisted of the elaboration of a structured registration form for the determination of the cultural values and the OUV of the buildings, for which the consideration of different publications was used (Díaz, 2016, pp. 49-52; INC, 2007, pp. 183-186; Junta Deliberante Metropolitana de Monumentos Históricos, Artísticos y Lugares Arqueológicos, 1962-1963; Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería, 1994). The file was validated and signed by four doctors with recognized national experience in cultural heritage of Peru: Alexander Henri Rodríguez Pérez, Bárbara Isabel Ponce Ponce, María Consuelo Albán Solís, and Mónica Elizabeth Regalado Chamorro.

Five other selected specialists, also with extensive experience in the nation’s cultural heritage and in the buildings of the Historic Center of Lima, filled out the form (Figure 3). Each one of the cultural values was qualified based on the authenticity and integrity of the patrimonial property, the similarity of the typology in the Historic downtown, as well as the use and function. The evaluation was high, medium, and low, with a weighting of 3, 2, and 1 respectively, following the criteria of Figure 4.

Figure 3 Structured file for recording immovable cultural heritage. Example of filling and evaluation of Casa Aspíllaga

(Registration Form: Ana María Lebrún, 2021; source: Díaz, 2016).

Figure 4 Criteria for filling out the structured Registration Form

| CRITERIA |

LOW 1 |

MEDIUM 2 |

HIGH 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Authenticity and Integrity | Presence of unaltered elements between 1% and 40% of the whole building | Presence of unaltered elements between 41% and 70% of the whole building | Presence of unaltered elements between 71% and 100% of the whole building |

| Similarity of the Typology | There are many examples of buildings with the same typology and with values of similar characteristics | There are a lot of similar buildings, but their typology presents particular characteristics | There are few models or its value is unique at national scale |

| Use and Funcion | They represent few references of collective and democratic appropriation of heritage; they maintain the traditional symbolic components; there is some conservation of the original meaning of the patrimonial building, but significant changes in its architecture and function | They represent several references of collective and democratic appropriation of heritage; they maintain the traditional symbolic components; there is conservation of the original meaning of the patrimonial building, and there are necessary changes in its architecture and function | They represent many references of collective and democratic appropriation; they maintain the traditional symbolic components; they preserve the original sense of the patrimonial building, without significant changes in its architecture and its function |

(Tabla: Ana María Lebrún, 2022; fuente: Díaz, 2016).

Finally, a survey aimed at national cultural tourists was designed and applied. Initially it was planned for international visitors, but it was not possible due to the closure of the buildings because of the pandemic and the consequent difficulty of virtually contacting these visitors. It was validated and signed by the same four experts who prepared the structured registration form. This had eleven main, closed questions, from which sub-questions were derived that together yielded fifty answers related to Peruvian heritage and the cultural values of the previously selected buildings. The information was statistically analyzed for its subsequent interpretation. Regarding the reliability of the survey, Cronbach’s Alpha was obtained to determine it in a pilot test with 30 participants, using the IBM® SPSS®2 26 version program (Cronbach, 1951, pp. 331-332).

Knowing the exact number of national tourists who visit the Historic Center of Lima is complicated, due to the large area and the lack of precise registration by the corresponding entities, such as the Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo (Mincetur, Ministry of Foreign Trade and Tourism). In this study, the data from 2019 was weighted, since the following year the pandemic began and, therefore, tourism in Peru fell by 76.8% (Daries, Jaime & Bucaram, 2021, p. 2). In 2019, 19’981 404 tourists visited the country, of which 7’880 117 arrived in the region of Lima and Callao (Perucamaras, 2020, p. 1). Of these, 56.8% correspond to national tourists (4’475 906). According to a 2019 study by the Dirección General de Investigación y Estudios sobre Turismo y Artesanía (2019) (General Directorate of Research and Studies on Tourism and Crafts), only 58% of national tourists who arrive in Lima visit the center, that is, 2’596 025 visitors.

To find out the opinion of national tourists regarding the values of immovable heritage buildings, a virtual survey was carried out on 101 people who were considered cultural tourists. The sample had a margin of error of 9.75% and a reliability rate of 95%. At first, it was planned to carry out the surveys in person, but the mobility restrictions resulting from the pandemic in Peru in 2021 forced them to be applied virtually through Google Forms. In this sense, the internet has opened the possibility of accessing new forms of research to specific groups, and it has been shown that the information generated can be very useful in answering research questions (Snee et al., 2016, p. 227). The survey was sent through social networks, through Facebook accounts and WhatsApp groups related to heritage, history, architecture, tourism, and culture.

Results

Immovable heritage buildings of the historic center of Lima

Of the 72 tourist heritage buildings of the Historic Center of Lima defined by the MML (2019), 17 were selected that meet the 8 criteria mentioned above. Figure 5 lists the buildings, and Figure 6 shows their location in the Historic Center.

Figure 5 List of cultural properties that meet the eight selection criteria. Editorial note: In the first column, the numbers in brackets correspond to the location

| TOURISTIC RESOURCES | LOCATION | DECLARATION OF CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE NATION | DATE | LOCATION WITHIN THE WORLD HERITAGE PERIMETER | IN USE SOCIAL/CULTURAL/RELIGIOUS | OPEN TO PUBLIC | WORKS AS PLACE OF BUSINESS | ASSOCIATED WITH A HISTORICAL CHARACTER OR EVENT | RECEIVES NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL TOURISTS | QUALITY HISTORICAL INFORMATION RELATED WITH THE IMMOVABLE HERITAGE BUILDING | BUILDINGS WHICH COMPLY WITH THE CRITERIA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MUSEUMS* | |||||||||||

| [6] Lima Cathedral (Museum of Religious Art of the Cathedral of Lima) | Jirón Carabaya Cuadra 2 s/n, Lima | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [7] Convent of San Francisco de Jesús “El Grande” (Museum and Catacombs of the Convent of San Francisco de Asís) | Esquina Jirón Lampa con Jirón Ancash, Lima | RS 1576-1941-ED | 17/09/1941 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [8] Church of Santo Domingo (Museum of the Convent of Santo Domingo) | Jirón Camaná 170, Lima | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [11] O’Higgins House (Museum of Art and Popular Traditions) | Jirón de la Unión 554, Lima | RJ 009-1989-INC/J | 12/01/1989 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [3] House Bodega y Quadra (Museum of Yestio Bodega y Quadra) | Jirón Ancash 213, Lima | RDN 1327-2004-INC | 03/12/2004 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [12] Museum of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru (Mucen-Central Museum) | Jirón Ucayali 299 esquina Jirón Lampa, Lima | RS 505-1974-ED | 15/10/1974 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [1] Archbishop’s Palace (Museum of the Archbishop’s Palace) | Jirón Carabaya Cuadra 2 s/n, Lima | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [5] House of Thirteen Coins (Afro-Peruvian National Museum) | Jirón Ancash 536, Lima | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [13] National Mint (Numismatic Museum of Peru) | Jirón Junín 781, Lima | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [2] Defenseless Station (House of Peruvian Literature) | Jirón Ancash 207, Lima | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| HOUSES AND BUILDINGS | |||||||||||

| [9] House of the Hearer (Museum of Chocolate) | Jirón Carabaya 187-189-193 esquina Jirón Junín 201-203-205, Lima | RS 505-1974-ED | 15/10/1974 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [14] Old Novitiate of San Antonio Abad (House of San Marcos) | Parque Universitario esquina Azángaro s/n | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [4] Aspillaga House (Inca Cultural Center Garcilaso de la Vega) | Jirón Ucayali 391 esquina Jirón Azángaro s/n | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [15] Congress of the Republic | Jr. Bolívar s/n, Lima | RM 329-1986-ED | 30/06/1986 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| CHURCHES | |||||||||||

| [16] Church of the Nazarenes | Huancavelica 507-515-517-521-537-549-561-573-575 esquina Avenida Abancay, Lima | RS 2900-1972-ED | 28/12/1972 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [17] Church of Our Lady of Mercy | Jirón de la Unión cuadra 6, Lima | RS 115-1959-ED | 07/04/1959 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

| [10] Saint Peter’s Church | Jirón Azángaro s/n esquina Jirón Ucayali s/n, Lima | RS 577-1959-ED | 16/12/ 1959 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Complies |

* In this column, the numbers in brackets correspond to the locations and names in Spanish, as shown in Figure 6.

(Table: Ana María Lebrún, 2021).

Structured record form

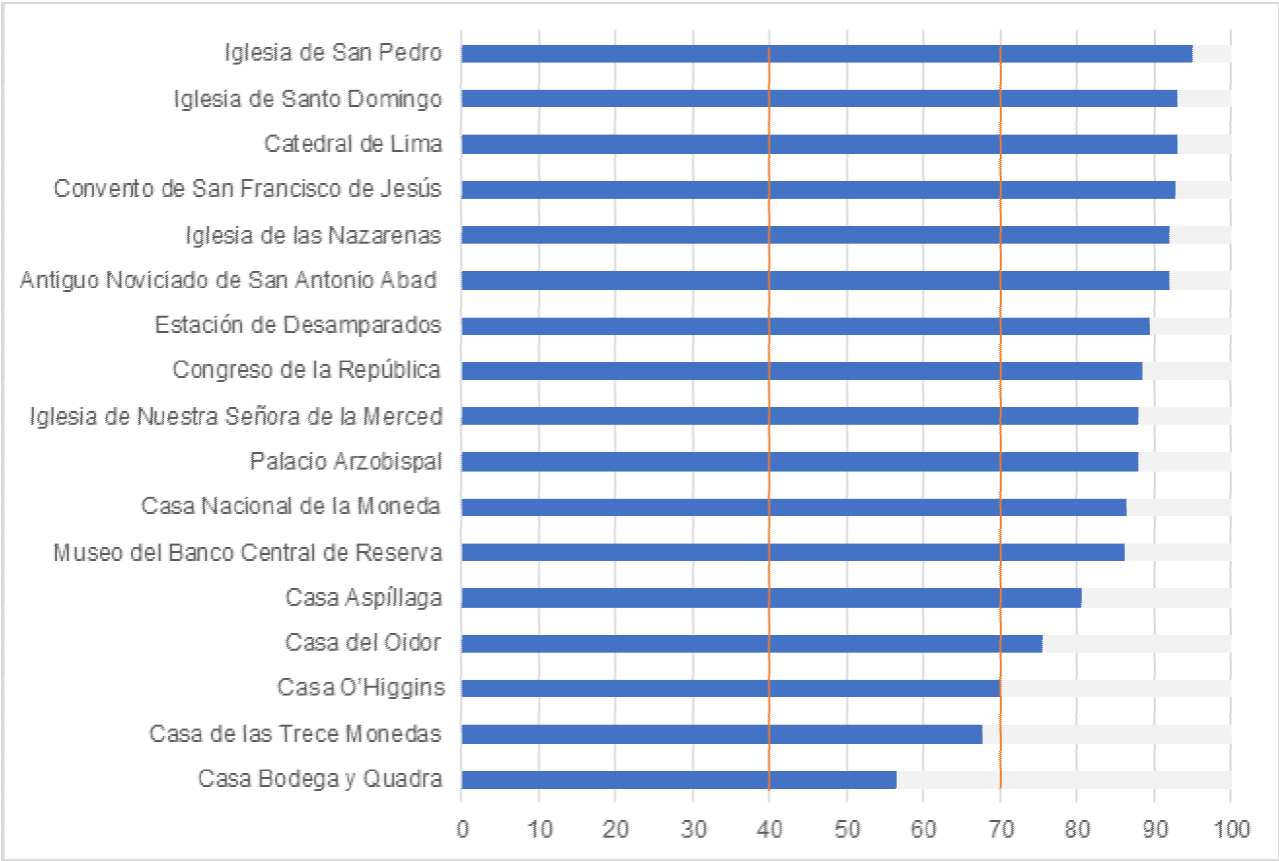

Figure 7 contains the evaluation made by experts regarding the total weighting related to the integrity and authenticity, typology, use, and function of each immovable heritage building, according to the antiquity, historical, architectural, technological, artistic, social, and aesthetic values.

(Map: Helga Geovannini, 2022)

Figure 7 Evaluation of the value of the 17 heritage buildings by specialists. Results are reported in percentages. The red lines define the intervals of low, medium, and high real estate value.

From this, 14 of the 17 buildings were evaluated highly for cultural values; three scored mediums; and none low. The buildings with the highest value correspond to the type of religious architecture, such as the church of San Pedro, the church of Santo Domingo, the Convent of San Francisco de Jesús “El Grande”, and the Cathedral of Lima. The churches and convents are considered unique, due to their architecture and artistic works, with various references to the collective appropriation of heritage, maintaining the traditional symbolic components. The Casa O’Higgins, the Casa de las Trece Monedas, and the Casa Bodega y Cuadra represent the buildings with the lowest value.

Regarding the cultural values of the heritage buildings, all of them were in a high range (a value between 2 and 3), where the historical ones stand out (2.7/3), followed by the architectural and technological ones (2.6/3), the aesthetic, artistic, and antiquity ones (2.5/3) and, finally, the social ones (2.4/3).

Survey related to the OUV and heritage values

After the analysis with a pilot test of 30 participants (100% valid, 0 excluded), the Cronbach’s Alpha value of the survey was 0.980, which shows 98% of reliability.

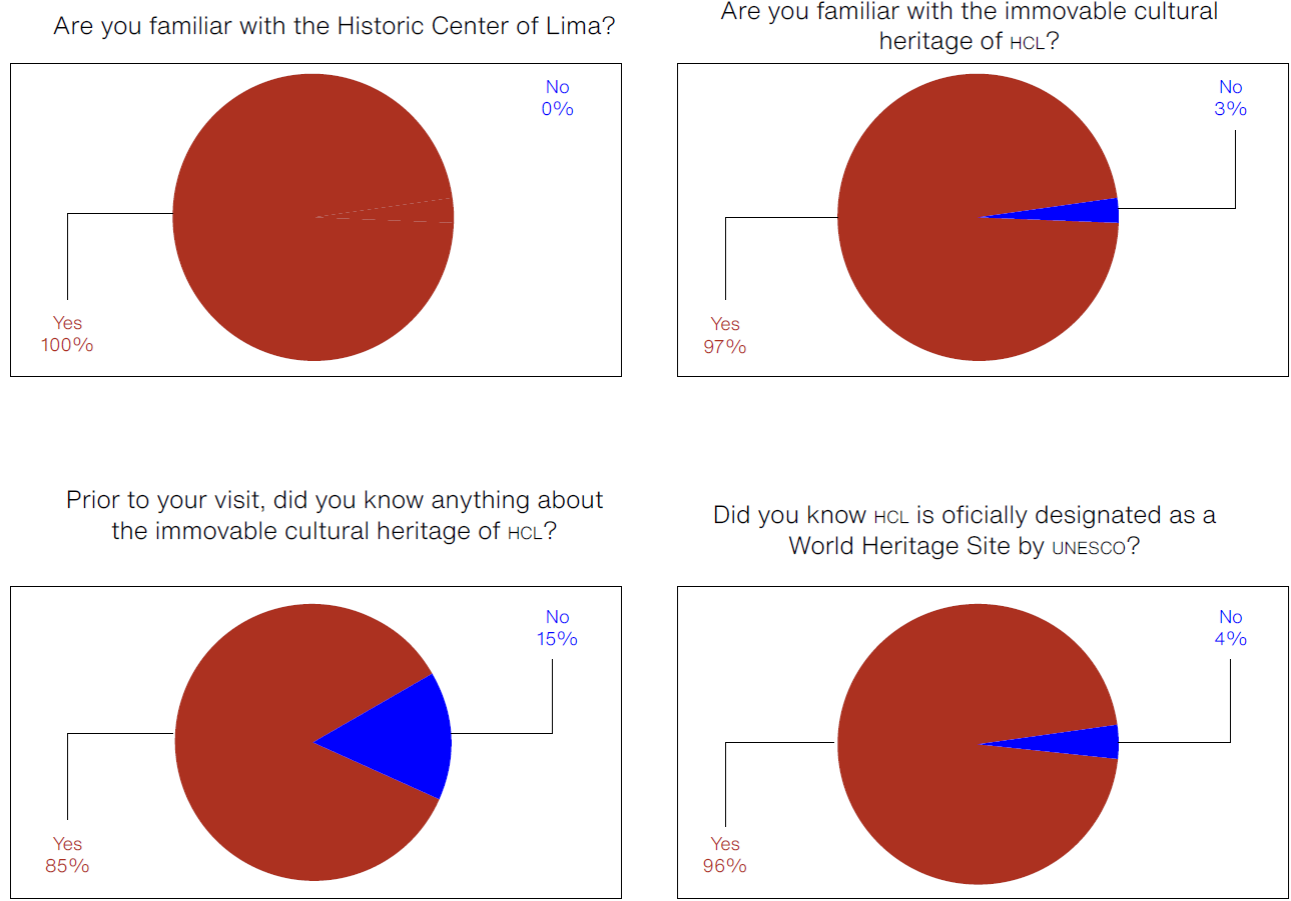

Going back to the virtual survey of 101 people mentioned above, 59% of the respondents identified themselves as women and 41% as men. The highest percentage of respondents is in the 45-54 age group, with 32%, followed by 35-44 with 29%, and 55+ with 25%; the lowest percentage of respondents is in the 18-24 age group, with 2%, and 25-34 with 13%. In terms of educational qualifications, 56% have a postgraduate degree, 38% a bachelor’s degree, 5% a technical level, and 1% a secondary level.

Figure 8 shows the results related to the knowledge of cultural tourists about the heritage of the Historic Center of Lima. Almost one hundred percent state that they know about this immovable cultural heritage and are aware that the Center belongs to World Heritage; 85% say they have prior information on it.

(Graphic: Helga Geovannini, 2022)

Figure 8 Knowledge of the Historical Center of Lima and its heritage.

Several questions related to the knowledge of the heritage properties of the Center were also asked, the answers to which are presented in a chart in Figure 9. Regarding this, it is observed a marked tendency to the knowledge of the buildings belonging to the Cultural Heritage of the Nation. Eleven buildings are known as heritage by more than 80% of those who made the survey, and the remaining six are known by more than 60% of them (Question 1).

(Graphics: Helga Geovannini, 2022).

Figure 9 Knowledge of the cultural values of the immovable heritage of the Historic Center of Lima

Regarding the knowledge of the seven cultural values associated with each of the buildings, the people who answered the surveys stated that they knew only between two and three (Figure 10, Question 2), mainly the historical and architectural ones. The social, the aesthetic, and the artistic have low appreciation as a value; while technological and seniority, almost none (Question 3).

(Graphics: Helga Geovannini, 2022).

Figure 10 Knowledge of the OUV and cultural values of the Historic Center of Lima

Regarding the OUV and the cultural values of the historic center of Lima to belong to the World Heritage (Figure 10, Question 1), more than 70% state that they know it in terms of its integrity, and more than 80% in terms of its age. From the people who answered the surveys, regarding the estimation that the cultural values and the OUV of the immovable heritage could motivate a renovation to increase tourism in the Historic Center of Lima, more than 70% “totally agree” and a little more than 20% “agree”. The percentage that neither agree nor disagree, or frankly disagree, is less than 5. Finally, when asked whether it is necessary to have different tourist routes to visit the immovable heritage of the Historic Center, around 75% state that they totally agree, more than 20% agree, less than 2% neither agree nor disagree, and 1% disagree (Figure 10, Question 3).

Discussion

Although there are 72 buildings defined as tourist resources in the Historic Center (MML, 2019), the 17 selected heritage buildings stand out because they are unique, special, and known by Peru vians. Many of them have multiple functions, among others, as places of worship, museums, and cultural centers.

The value of these 17 heritage buildings given by the experts in their different aspects is high. This means that, in general, the buildings are in a good state of conservation, that they are unique, special or represent references of collective appropriation. Only around 20% of them were considered to have a medium value (Casa O’Higgins, Casa de las Trece Monedas, and Casa Bodega y Quadra), in the sense that even though their qualities are not recognized as unique, they could be reinforced. These buildings could be targeted to carry out the necessary actions to highlight their importance and improve their state of conservation. In the case of the historical, architectural, artistic, aesthetic, technological, social, and age values of the properties, the specialists considered that they are all high.

The survey was useful both to find out the opinion of national cultural tourists regarding the heritage and value of the Historic Center of Lima and to confirm their degree of interest and know ledge regarding Lima’s immovable heritage. The fact that it was virtual provides some limitations, since it does not represent all potential national tourists interested in culture, and because it asks people with internet access and interest in the cultural field. Nonetheless, it has previously been identified that cultural tourists are highly educated adults seeking a more detailed cultural understanding of the place they are visiting (McKercher, 2002, p. 37).

In general, all the respondents know about the Historic Center of Lima: that it is a World Heritage site, about the immovable heritage, have some information about it, and are aware of the cultural values and the OUV. Even when asked about the buildings belonging to cultural heritage, more than 80% of the respondents knew eleven heritage buildings as such, and more than 60% of them knew the remaining six.

Nevertheless, when asked about the seven different values associated with each of the buildings, it was found that the cultural values were largely unknown. Of all of them, only the historical and the architectural ones are recognized, which leaves a potential to highlight the other values that are present and that we know, according to the opinions of the experts.

Regarding whether the respondents believe that the cultural values and OUV of the immovable heritage could generate a renovation and increase tourism in the Historic Center of Lima, about 90% agree that it is possible, while 95% believe that it is necessary to have different tourist routes to visit and learn about the immovable heritage of the Historic Center. Although since 2015 the MML, through the Tourism Sub-Management, has been developing tourist routes and tours specifically for local and national visitors (MML, 2019, pp. 319-333), it is necessary to multiply efforts, propose new routes, and offer more options to foreign tourists.

Conclusions

The Historic Center of Lima is a special and attractive destination that has an immovable heritage as a unique tourist focus. The values associated with the heritage of this site are crucial for their full appreciation, which is why studies and research on them are urgent. In addition to this, the fact that the lack of information and knowledge about these associated cultural values, the lack of appreciation, consideration, and understanding of their meanings, and, above all, the absence of concrete actions by public and private institutions have led to a significant deterioration of this remarkable place, threatening its survival, although its essence (intangible) and its appearance (tangible) remain after the passing of the years.

The recognition of cultural values and the OUV by all the stakeholders (inhabitants, visitors, authorities, public and private institutions, to name a few) is a relevant and irreplaceable element for tourism renewal, whose purpose is to visit the immovable heritage of the Historic Center of Lima and identify its differentiating features-which make it more attractive. This will allow the consolidation of the area so that it is known, traveled, and consumed by national and foreign cultural tourists.

In particular, the analysis of cultural values will promote the possible renewal of cultural tourism through the improvement and creation of new circuits, itineraries, or tourist routes that, in turn, reinforce the different values associated with the properties. In this way, the visitors will be able to enjoy a World Heritage Site that belongs to them to be respected, preserved, and passed on to future generations, as a social and cultural reality in a permanent state of evolution.

REFERENCES

Ballart, J. (1997). El patrimonio histórico y arqueológico. Valor y Uso. Ariel. [ Links ]

Choay, F. (2007). La alegoría del patrimonio. Gustavo Gili. [ Links ]

Cronbach, L. (1951). Coefficient Alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16(3), 297-334. [ Links ]

Dammert, M. (2018). Precariedad urbana, desalojos y vivienda en el centro histórico de Lima. Revista INVI, 33(94), 51-76. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-83582018000300051 [ Links ]

Daries, J., Jaime, V. y Bucaram, S. (2021). Evolución del turismo en Perú 2010-2020, la influencia del covid-19 y recomendaciones pos-covid-19. Nota técnica IDBa-TN-02211. Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo. https://publications.iadb.org/publications/spanish/document/Evolucion-del-turismo-en-Peru-2010-2020-la-influencia-del-COVID-19-y-recomendaciones-pos-COVID-19-nota-sectorial-de-turismo.pdf [ Links ]

Díaz, D. (2016). Diseño de herramientas de evaluación del riesgo para la conservación del patrimonio cultural inmueble: aplicación en dos casos de estudio del norte andino chileno. ENCRyM-INAH/Secretaría de Cultura. https://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/libro%3A836 [ Links ]

Dirección General de Investigación y Estudios sobre Turismo y Artesanía. (2019). Nivel de satisfacción del turista nacional y extranjero que visita Lima. Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo de Perú. https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/1021388/Lima-Nivel-Satisfaccion-Turista-2019.pdf [ Links ]

García, N. (1999). Los usos sociales del Patrimonio Cultural. En E. Aguilar Criado (Coord.), Patrimonio Etnológico. Nuevas perspectivas de estudio (pp. 16-33). Consejería de Cultura-Junta de Andalucía. http://bibliotecadigital.academia.cl/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/617/Nestor%20Garcia%20Canclini.pdf?sequence=1 [ Links ]

Günther, J. y Lohmann, G. (1992). Lima. Mapfre. [ Links ]

IBM. (2023). Software IBM SPSS. https://www.ibm.com/mx-es/spss#:~:text= La%20plataforma%20de%20software%20IBM,implementaci% C3%B3n%20sin%20interrupciones%20en%20aplicaciones [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Cultura. (2007). Documentos fundamentales para el Patrimonio Cultural. Textos internacionales para su recuperación, repatriación, conservación, protección y difusión. INC. https://oibc.oei.es/uploads/attachments/276/patrimonio_cultural_per%C3%BA.pdf [ Links ]

International Council on Monuments and Sites. (1991). Advisory Body Evaluation. World Heritage Convention [página web]. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/500/documents/ [ Links ]

Jokilehto, J. (2017). Valores patrimoniales y valoración. Conversaciones…, (2), 20-32. https://revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/conversaciones/article/view/10885 [ Links ]

Junta Deliberante Metropolitana de Monumentos Históricos, Artísticos y Lugares Arqueológicos de Lima. (1962-1963). Informes sobre los monumentos republicanos y coloniales de Lima (1 y 6). La Junta. [ Links ]

Mayordomo, S. y Hermosilla, J. (2019). Evaluación del patrimonio cultural: la Huerta de Valencia como recurso territorial. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 82, 1-52. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=7042646 [ Links ]

McKercher, B. (2002). Towards a classification of cultural tourists. International Journal of Tourism Research, 4(1), 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.346 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Cultura. (2017). Identificación y declaratoria del Patrimonio Histórico Inmueble. Épocas Colonial, Republicana y Contemporánea. Dirección General de Patrimonio Cultural [página web]. http://repositorio.cultura.gob.pe/handle/CULTURA/753 [ Links ]

Municipalidad Metropolitana de Lima, Programa Municipal para la Recuperación del Centro Histórico de Lima-ProLima y Lima Ciudad para Todos. (2014). Plan maestro del Centro Histórico de Lima al 2025. ProLima. MML. https://www.academia.edu/32980408/PLAN_MAESTRO_DEL_CENTRO_HIST%C3%93RICO_DE_LIMA_AL_2025 [ Links ]

Municipalidad Metropolitana de Lima. (2019). Plan Maestro del Centro Histórico de Lima al 2028 con visión al 2035. II Diagnóstico del Centro Histórico de Lima. ProLima. MML. https://aplicativos.munlima.gob.pe/uploads/PlanMaestro/plan_maestro_resumen_ejecutivo.pdf [ Links ]

Negro, S. (2019). Reflexiones sobre el patrimonio cultural del Perú, contextos y perspectivas. Tradición, segunda época, (19), 170-171. https://revistas.urp.edu.pe/index.php/Tradicion/article/view/2636 [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. (1972). Convención sobre la protección del patrimonio mundial, cultural y natural. UNESCO. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. (2008). Directrices Prácticas para la aplicación de la Convención del Patrimonio Mundial. Centro del Patrimonio Mundial-UNESCO. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. (2014). Indicadores UNESCO de Cultura para el Desarrollo. Manual Metodológico. UNESCO. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Educación, la Ciencia y la Cultura. (2019 [2023]). La visión de UNESCO para el Centro Histórico de Lima [página web]. UNESCO. [ Links ]

Organización Mundial del Turismo. (2019). Definiciones de turismo de la OMT. OMT. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420858 [ Links ]

Perucamaras. (21 de abril de 2020). Llegada de turistas aumentó 8.1% en el 2019 [página web]. https://www.perucamaras.org.pe/nt390.html [ Links ]

Rico, E. (2014). El patrimonio cultural como argumento para la renovación de destinos turísticos consolidados del litoral en la provincia de Alicante (Tesis doctoral). Universidad de Alicante. http://rua.ua.es/dspace/handle/10045/40780#vpreview [ Links ]

Rico, E. y Baños, C. (2016). El patrimonio cultural en los procesos de renovación de áreas turísticas litorales. Una aproximación al destino turístico de la Costa Blanca (Alicante, España). Cuadernos Geográficos, 55, (2), 299-319. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/171/17149048014.pdf [ Links ]

Riegl, A. (1987). El culto moderno a los monumentos. Visor. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, M. (2019). Centro Histórico de Lima (1991). En M. Rodríguez Cuadros (Ed.), El Perú en el sistema internacional del patrimonio cultural y natural de la humanidad. Universidad de San Martín de Porres/Fondo Editorial. [ Links ]

Ruiz, A. y Pérez, M. (2021). Impacto turístico del Valor Universal Excepcional de las ciudades patrimoniales de México. Kalpana. Revista de investigación, (20), 30-49. https://publicaciones.udet.edu.ec/index.php/kalpana/article/view/41/202 [ Links ]

Shimabukuro, A. (2015). Barrios Altos: caracterización de un conjunto de barrios tradicionales en el marco del Centro Histórico de Lima. Revista de Arquitectura, 17(1), 6-17. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/1251/125143817002.pdf [ Links ]

Sizzo, I. A. (2013). Colonial y animado: percepción del Centro Histórico de Morelia entre los residentes de la ciudad. Journal of Latin American Geography, 12(3), 113-135. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24394888 [ Links ]

Snee, H., Hine, C., Morey, Y., Roberts, S. y Watson, H. (Eds.) (2016). Digital Methods as Mainstream Methodology: Conclusions. En Digital methods for Social Science: An Interdisciplinary Guide to Research Innovation. Palgrave Macmillan London. [ Links ]

Universidad Nacional de Ingeniería, Facultad de Arquitectura, Urbanismo y Artes. (1994). Inventario del Patrimonio Monumental Inmueble-Lima. Valles de Chillón, Rímac y Lurín. Fundación Ford. [ Links ]

Vera, P. (2015). Estrategias patrimoniales y turísticas: su incidencia en la configuración urbana. El caso Rosario, Argentina. Territorios, (33), 83-101. https://revistas.urosario.edu.co/index.php/territorios/article/view/3352/3088 [ Links ]

Vilcapoma, T. (2018). Ubicación de los 17 inmuebles patrimoniales [mapa inédito]. Copia en posesión de la autora. [ Links ]

Villalba, M. (2016). Una aproximación al Patrimonio Cultural en relación con la competitividad de los destinos turísticos. Especial atención al contexto español. Esic Market Economics and Business Journal, 47(2), 331-354. https://www.esic.edu/documentos/revistas/esicmk/160706_040739_E.pdf [ Links ]

Vit, I. (2017). La revaloración del patrimonio arquitectónico. Una mirada holística a sus componentes tangibles e intangibles. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

2Big data integration and seamless deployment into applications are some of the features offered by the IBM® SPSS® software platform. Its ease of use, flexibility, and scalability make SPSS accessible to users of all skill levels. Furthermore, it is suitable for undertaking projects of varying sizes and levels of complexity (IBM®, 2023).

Received: June 29, 2022; Accepted: June 22, 2023; Published: September 30, 2023

texto em

texto em