Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Intervención (México DF)

versión impresa ISSN 2007-249X

Intervención (Méx. DF) vol.13 no.25 México ene./jun. 2022 Epub 13-Feb-2023

https://doi.org/10.30763/intervencion.265.v1n25.44.2022

Academic report

The Issue of Unknown Landscapes in the Online Cataloging of the National Art Museums of North America

* Universidad de Guanajuato (UG), México, mrabadan@ugto.mx

This academic report is a part of a research, from the perspective of visual studies, on landscape art of modernity and after it in the Western tradition. This work proposes to analyze, in accordance with the structuralism of Thomas Kuhn, the change in visual Gestalt of the beginning of the 20th century related to the articulation in art of a new paradigm. The visualization cuts across the curating and the cataloging of online collections of the National Art Museums of North America, questioning the differential perception of structuring the abstract and the conceptual in the landscape between collections. However, this study finds a theoretical solution to the phenomenon of the invisibility of images in episodes of a non-accumulative nature, typical of paradigmatic changes, according to Kuhn’s model.

KEYWORDS: national art museums; curatorship; landscape art; visual Gestalt; Thomas Kuhn

Este informe académico es parte de una investigación, desde la perspectiva de los estudios visuales, sobre paisajismo de la modernidad y después de ella en la tradición occidental. Se propone analizar, de acuerdo con el estructuralismo de Thomas Kuhn, el cambio de Gestalt visual de principios del siglo XX relativo a la articulación en el arte de un nuevo paradigma. La visualización atraviesa la curaduría y la catalogación de colecciones en línea de los museos nacionales de arte de Norteamérica, cuestionando el diferencial de percepción de la estructuración de lo abstracto y lo conceptual en el paisaje entre estos acervos. No obstante, este estudio encuentra una solución teórica al fenómeno de invisibilidad de las imágenes en los episodios de carácter no acumulativo, propios, nuevamente según el modelo de Kuhn, de los cambios paradigmáticos.

PALABRAS CLAVE: museos nacionales de arte; curaduría; paisajismo; Gestalt visual; Thomas Kuhn

To make a collection is to find, acquire, organize, and store objects, be it in a room, a house, a library, a museum, or a warehouse. It is also, inevitably, a way of thinking about the world -the connections and principles that a collection produces contain assumptions, juxtapositions, experimental possibilities of discovering and associating. Making a collection, you could say, is a method of producing knowledge

The makeup of the landscape as an inherent part of visual arts underwent an epistemic2 and paradigmatic change at the beginning of the 20th century, which was originally structured in the works by artists who during modernity integrated the avant-garde movements, and those who were not part of them, yet whose works are articulated in certain ways that configure various formal Gestalt incompatible with the art of modern times3. Some examples of these revolutionary works are Depósito de agua. Horta de Ebro (The Reservoir. Horta de Ebro), 1909, by Pablo Picasso (Collection Modern Museum of Art); Graue Landschaft (Grey Landscape), 1912, by Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (Hamburger Kunsthalle); Paesaggio (Landscape), 1913, by Giorgio Morandi (Museo del Novecento); Composition 10 in Zwart Wit (Composition 10 in Black and White), 1915, by Piet Mondrian (Kröller Müller Museum); Wald Bau (Forest Construction), 1919, by Paul Klee (Museo del Novecento); Air de Paris (Air of Paris), 1919, by Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia Museum of Art); L’espoir rapide (Swift Hope), 1927, by René Magritte (Kunsthalle), or Study for Tenayuca, 1940, by Joseph Albers (The Joseph & Anni Albers Foundation).

These works changed completely, by taking shape in the context of new theories that stopped adding knowledge to what was known about art until then; these works were more related to the idea of painting and its function of representing movements ranging from romanticism or modern painting characteristic of Edouard Manet and the Impressionists and Post-Impressionism, up to Cubism. With abstract, conceptual, and naturalistic thinking and its possible combinations, the entire visual system is transformed into works that are contrary and incompatible with those of the modern age4. The perception of this set of visual systems has been encrypted in this way before the gaze of those who did not cognitively accommodate themselves to the new theories of art.

However, being defined by its differentiation from the cumulative change that will henceforth build the paradigm after modernity, this non-accumulative change fundamentally requires, for its understanding, examples of the relationship between both types of movement. According to Kuhn’s structuralism: “Revolutionary change is defined in part by its difference from normal change, and normal change is, as indicated, the kind of change that results in the cumulative growth, increase, or addition of what was known before” (1996, p. 57). Normal changes, unlike the revolutionary ones, holistic, but they change parts, while the visual Gestalt remains, and it is possible to examine which part has been the normal innovation. The structural aspects of the paradigm would therefore be incomprehensible without researching the landscape of modernity and that of post-modernity5.

Curation, which as a research method has a solid track record, forms a warp and woof in this work with Kuhn’s structuralism. In that sense, he examines the paradigmatic of works like Atlas eclipticalis by John Cage. This is a post-modern work, whose score is paradigmatic of the first examples contrary to the theoretical model of the modern era, such as Erratum Musical, 1913, by Marcel Duchamp. The Atlas is a pentagram with unprecedented numerical notations that, according to his instructions, must use chance to create a new musical alphabet. Writing on a musical pattern had never been considered visual art, but it began to be seen as such from the Duchampian conception. In terms of structuralism according to Kuhn, in the changes of vision associated with revolutionary changes, new things are perceived where they had previously been seen (Kuhn, 1995, p. 176). The artistic community articulates the paradigm in its evolution in the objectification of its work and the integration of its archives. After being created as a Duchamp document, Erratum Musical forms the John Cage archive, before being donated to the collection of the Foundation for Contemporary Performance Arts, in New York, and informing the Philadelphia Museum of Art that, by housing, the most important French artist, is responsible for his catalog raisonné (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1989, p. 264). That said, it is worth mentioning the contribution of Walter Arensberg’s collections and the curatorship of Anne D’Harnoncourt to said museum, which would not have been consolidated without this set of collaborations.

In his lecture “Comments on Relations of Science and Art”, Thomas Kuhn thought that if the notion of paradigm could be useful for art history, it would be images and not style that would serve as paradigms (1958, p. 351). In this sense, this research in a historical context agrees with Kuhn’s observation: the study of the collections of the national museums of North America goes through one by one the landscape works from which he bases his own theory and method on the landscape to structure the paradigm of the works of modernity and after modernity, of which landscape art, he said, is a segment.

The altered perceptions in Kuhn’s model have seemed extremely important to me in visualizing how landscape art crosses these holistic changes-which, from my point of view, happen mainly between 1907 and 1915. The knowledge of these Gestalt changes subconsciously led to restructuring my perception before works of modernity and after modernity, such as Marcel Duchamp’s Unhappy Ready-Made, 1919 (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1989, p. 288), or Gazing at the Skyline, Sky Ground, Australia, 1982, by Hamish Fulton (Photoplay. Works from The Chase Manhattan Collection, 1993, p. 73). On the other hand, what makes me see the permanence of what is landscape in these works is the understanding of the component of that artistic practice in Landscape into Art (1991), the work of Kenneth Clark, who in his study that goes from Gothic to modernity affirms that exceptional sense of our being in the landscape, of our being able to proceed (visually) smoothly from foreground to distance (1991, p. 32). This agrees with Kuhn’s model, who comments how, from the historiography of science, the scientific component is thought of in previous paradigms: “The more detailed they study, for example, Aristotle’s thermodynamics [...], the more certain they feel that those once current visions of nature were not globally considered neither less scientific nor more the product of human idiosyncrasy than the current ones” (1995, p. 22).

During modernity and after modernity, artists in general have not stopped visualizing the landscape. On the contrary, what has ignored this creation after the change of formal Gestalt has been the avant-garde conception of art history6: there are specific cases of curatorship in the field of museology, or of a certain artistic community, which did not assimilate the theoretical change and perception, or paradigm, and continued to work on a 19th-century image system.

The avant-garde conception of history basically perceives landscape art in the work of the new, more naturalist avant-gardes, such as Land Art, Earth Art and Environmental Art, but not that of other artists, such as La Mia Ombra Verso l’Infinito Dalla Cima Dello Stromboli Durante L’Alba del 16 Agosto 1965 (Study F) (My Shadow Towards the Infinity of the Peak of Stromboli During Dawn), 1965-2000, by Giovanni Anselmo (Museum of Modern Art); Ten Landscapes, 1967, by Roy Lichtenstein (Museum of Modern Art); First edition for screen TV, 2012, by David Hockney (Hockney, 2012); Buchen Federal District, by Anselm Kiefer (Shama, 1995, p. 19); Without Horizon 6, 1992, by John Cage, or A flor de piel (Skin Deep), 2011-2012, by Doris Salcedo (Harvard Art Museums). Although this conception of history has been the canonical basis in academic teaching on art in the last century, it is questioned not only by this research project: it was already so since the 1980s by authors such as Hervé Fischer (L’Histoire de l’art est terminée, 1981) or Hans Belting (The End for the History of Art?, 1987).

The problem with the invisibilization of these changes is a particular type of social revolution study carried out by Thomas Kuhn, in which he discovered a similarity in relation to the innovative character of the scientific field. He analyzed how paradigmatic changes are not visible to those who are not affected by them, and how, in order to assimilate the evolution of said changes and choose between paradigms that are incompatible, institutions have to transform. Likewise, he examined how evaluation processes also depend on paradigms (1995, pp. 150-151). That is, all the functions of the museum institution-collecting, identifying, registering, cataloging, investigating, exhibiting and educating-assimilate their own paradigmatic structure. His aim is to connect cultures that are contemporary to them or cultures that are not contemporary to them; however, when the works come from those whose paradigms are entirely different, they can be made invisible, as happens before abstract or conceptualist landscapes to scholars accustomed to painting naturalistic landscapes.

I limit this stage of this research to the three national museums of North America, since it is my geographical area: the National Museum of Art in Mexico City, the National Gallery of Art in Washington and the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, whose typology is referring to museums or art galleries that house paintings, drawings, prints, sculpture, photography, ceramics, video art, net art, installations, or specific sites, among others. Though one cannot help but think of the disparity of the comparison in terms of the antiquity of the museums, their sociocultural context or other factors, this contrast has a qualitative approach, fundamentally focused on the study of the conception of the landscape in modernity and after modernity in the field of curatorship.

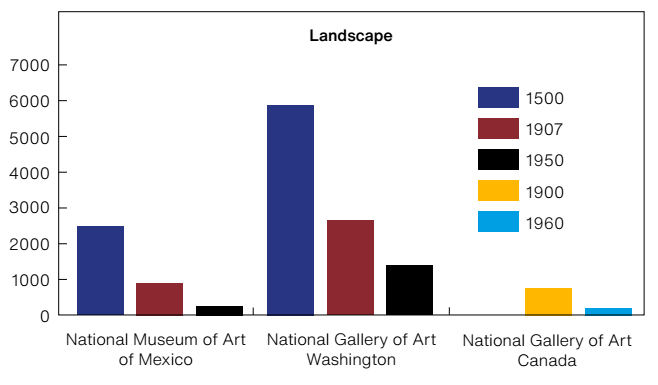

The online catalogs of the collections of the national museums of North America can be analyzed under the term landscape. In this way, it is possible to access the examination of the curatorial orientation of the collections. For the purposes of this research, during 2020 I filtered the said word in the following periods: 1500-1907; 1907-1950/1960; 1950/1960-2020. These include the dates of the collections of the three national museums, regardless of their various foundation dates and considering the year 1907, when the paradigmatic change began according to this study (Rabadán, 2017), and 1950, the last decade of the collection of the National Museum of Art in Mexico City. The National Gallery of Canada may be selected every 20 years, so we determined 1960 for that catalog. In any case, the analysis considers that the image of the works has been included in the online catalog record.

(Graphic: María Eugenia Rabadán Villalpando, 2020)

FIGURE 1 Graphic representation of online search results for the landscape category in the national art museums of North America.

The National Museum of Art (Munal) in Mexico City, opened in 1981, houses a collection of more than 6,000 works of Mexican art dated between the second half of the 16th century and 1954. In order to extend academic research on the collection, since 2017 the Museum digitizes and publishes the catalog online (Munal, 2017). On its website, the museum states its mission as follows: “The National Museum of Art preserves, exhibits, studies and transmits works of Mexican art produced between the second half of the 16th century and 1954, thus offering a synthetic global vision of Mexican art from this period” (MNA, 2022). On its platform, the Munal collection is eligible for disciplines, artists and registered works. The advanced search understands, among its terms, landscape, and shows 99 works, from the oldest, by Joaquín Clausell-of unknown date-, to Paisaje de Contreras Número 2 (Landscape of Contreras Number 2), 1962, by Amador Lugo Guadarrama. Without the term landscape, and only for the dates 1907-2000, it chooses other examples of landscapes, but only two of interest for this analysis: Después de la tormenta (After the Storm), 1910, by Diego Rivera (Munal); Líneas de teléfonos (Telephone Lines), ca. 1925, by Tina Modotti (Munal).

The origin of the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. dates back to 1937, when the Congress of the United States of America accepted the initiative of Andrew W. Mellon to donate works-126 paintings and 26 sculptures, according to the preliminary annotated catalog (Richter, 1941, p. 177)-and President Franklin D. Roosevelt to create a fund of works of art for that country. It houses in its collection an international collection of 150 000 paintings, sculptures, decorative arts, photographs, prints, drawings and Time-Based Media Art, from Byzantine art to the present. That National Gallery of Art defines its mission in these terms: “it serves the nation by welcoming all people to explore and experience art, creativity, and our shared humanity” (National Gallery of Art, 2020). According to the Gallery’s online cataloging, the following categories are eligible: highlights, collection search, artist and acquired highlights, and has a blog (Collection, 2020). In the collection search engine, the collection is entirely eligible by author’s last name, keywords in the title, keywords in the object information, credit line, name of provenance-the history of the owners of the works is an ongoing research and includes a study of the provenance of the works in the collection in World War II-, acquisition number, exhibition history, online editions and/or catalog raisonné. Among these options, in the “keywords in the object information”, the term landscape filters 5 794 works from 1320. The search can also be narrowed down by online images, classification, nationality, online editions, years, styles, photographic processes, locations, themes, alternate numbers. For the purposes of this research, at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, I filtered landscapes in the following periods: 1320-1907: there are 3 161 works; between 1907 and 1949, 1 247; and in the period 1950-2020, 1 431 works7.

In the Museums Act, within the Purposes, Capabilities and Powers of the National Gallery of Canada and its affiliate, the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography, the Government of Canada defines the acquisitions policy in these words: “The purposes of the National Gallery of Canada are to develop and maintain and make known, throughout Canada and internationally, a collection of works of art, historical and contemporary, with special emphasis but not exclusive reference to Canada, and for the further knowledge, understanding and enjoyment of art generally for all Canadians” (Government of Canada, 1990, p. 1). In those same purposes, the Government postulates the capacity of the museum to develop research, basic or fundamental, theory and applied research related to its purposes and museology, and to communicate the results of the research. The Gallery’s mission is stated as follows: “Through the visual arts, we create dynamic experiences that open hearts and minds and enable new ways of seeing each other and our diverse stories” (National Gallery of Canada). The National Gallery of Canada’s online records number 63,150 works from before 1700 to the present. It has a new online platform, whose filters are the name of the artist, the title of the work, access number, and recognizes the term landscape. From the result, the following filters are found: artists, media, categories, in periods of 20 years. Once the collection has been delimited to landscapes, what it is possible to choose is the temporality, and then select a link with works by artists, such as 64, from 2000 to the present; 78, from 1980 to 1999; 62, from 1960 to 1979; 102, from 1940 to 1959; 250 from 1920 to 1939, and 282 from 1900 to 1919.

Methodologically, this research aims to make visible in the formation of these collections the state of assimilation of landscape art after the paradigmatic change included in modernity and after modernity. Said museum work, manifested in its digitized transmission networks, in a printed publication or, in a face-to-face exhibition, silently alludes to the documentary techniques that underlie the construction of knowledge of the works. The former function is based on the conceptualization and visualization of the artistic community, and interpret the pieces during the identification, registration, inventory, cataloging, graphic documentation of the object8, and from the flow of this chain of documentation to the public dissemination of the museum collections.

The databases of museum collections, fundamental both for scientific study and for the general dissemination of knowledge, are susceptible to replication from scientific study. Curating, by its nature, is a discipline that tends not only to globalization, but, in the context of a constant miscegenation of different cultures, to be the conjunction of them. The display of their databases on the World Wide Web enhances this feature through the exchange of information. This leads us to think about the importance of carrying out cross-sectional studies on various museums, rather than on one in particular, aware of the cultural changes and the identities that each culture can preserve.

The following are not all the results, but a model of found works that, on the one hand, prove the continuity of the landscape through the different abstract, conceptual and naturalistic image systems, and, on the other hand, go beyond all kinds of possible combinations and media, even the new digital media.

In the advanced search of its website, after 1907, the National Museum of Art records Paisaje urbano (Urban Landscape), 1925, a view with a certain metaphysical abstraction, by Frida Kahlo; the cubist works with available images are Paisaje de Taxco-La aduana (Landscape of Taxco-Customs) (1933), by Amador Lugo Guadarrama (Munal), and Paisaje zapatista (Zapatista Landscape) (1915), by Diego Rivera (Munal)9; Paisaje nocturno (Nightscape), 1938, metaphysical, by Carlos Orozco Romero (Munal). These are the pieces cataloged until 1950 that show a change in the visual arts through the landscape10, but, as they do not have a normalization pattern according to Kuhn’s structuralism, it is not possible to see in these examples only a paradigmatic change, as we have tried before. A search for the dates 1907-1950 without the term landscape selects other examples of landscapes, such as: After the Storm, 1910, by Diego Rivera (Munal); Telephone Lines, ca. 1925, by Tina Modotti (Munal)-this photograph is of interest because, as in another work by Modotti, the horizon disappears; it is the problem posed by Malévich for the Black Square, 1915-. It is important to point out that in the collection of the National Art Museum, the only example of a change of perception in an artist in the context of landscape painting would be given in the difference in the image system of Después de la tormenta (After the Storm) and Paisaje zapatista (Zapatista Landscape), by Diego Rivera. Between both works there was in Rivera a restructuring of perception, as there was in other modern artists, such as Pablo Picasso in the portrait Gertrude Stein, 1906, and in Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon), 1907. In this sense, it is worth mentioning that Riviera’s Zapatista Landscape, for example, is quite close to Juan Gris’s Ace of Clubs and Four Diamonds in the National Gallery of Art collection, so if these two works are put together, they can begin to form a theory visual on the cubist landscape in a curatorial script. James Elkins has worked the visual as an argument he intelligently theorizes, where one image explains another. It takes the idea from a work by Leo Steinberg on The Last Supper, by Leonardo, in which copies of that painting, such as engravings, paintings, etchings, photographs, intervene in the argument or theory about the mural of Santa Maria delle Grazie, in Milan; that is, these images explain the painting, for which they are recognized as intelligent theories (2013, p. 32). In this sense, the visual perception of the sudden and complete change of Gestalt in the images of the visual arts from the beginning of the last century has been a fundamental intelligent theory to problematize this new conjecture about the landscape. The historical conception of avant-garde has not been able to see landscape in the works of North American abstract expressionism, conceptual art, arte povera, German neo-expressionism, to cite paradigmatic examples of revolutionary change, which are not Land Art, Earth Art nor Environmental Art.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington has a rich collection of postmodern landscapes, such as the following examples, including some abstract ones: Lee Mullican’s Meditations on a Landscape (1964) (1984.34.394)11; Landscape (1965), by Bruce Conner; Persian Garden (1965-1966), by Helen Frankenthaler (1976.56.34); a fairly complete collection of works such as Untitled (1969), by Mark Rothko (1986.43.295); Landscape at Stanton Street (1971), by Willem de Kooning (1975.104.7); it is understandable in the landscape subcategory, even when seen from a restructured perception. It houses works that capture combinations of naturalism and abstraction, possible after the beginning of the last century, such as Moonscape (1965), by Roy Lichtenstein (1991.239.3), and Landscape of Baucis (1966), by René Magritte, or Paysage de Baucis (1994.63.5), is a work of great interest, because the title has nothing to do with the image, as was most of Magritte’s work, addressed in an essay by Michel Foucault (1981). The articulation of these parallel paradigms through modernity and the landscape after modernity can be understood if we associate Malévich’s Black Square, 1915, and John McCracken’s Black Plank (1967), in which the horizon disappears. Haystack (1969), by Roy Lichtenstein (1985:47.113), is a paradigmatic monochrome work; Meules, fin de l’été (Mills, End of Summer), 1891, by Claude Monet, in front of which in 1896 Kandinsky discovered the color in painting and began to restructure his perception towards the disappearance of objects and, 14 years later, towards the discovery of the abstract (1994, p. 363). It is one of the most extraordinary restructurings of perception in the history of modernity and after modernity, of which landscape art is a fraction.

The National Gallery of Canada and the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography have clearly defined collection areas for Canadian and international art, contemporary art, and historical art. Within the first, they consider that of the Inuit American aborigines and the migratory movements to Canada of Asian and non-Western communities and consider the study of their origins to be relevant. The aesthetic quality and historical importance of acquisitions are regulated by the Act, and, with knowledge of the matter, the document affirms that the works must be of the highest possible nature in relation to their position within the artist’s work in the historical period and, finally, within its cultural tradition, and that the works should be recommended for their exceptional historical importance.

The National Gallery of Canada classifies his acquisitions in the Index of The Burlington Magazine (Volume Information, 1941). They have sometimes been commented on by critics such as Paul Oppé, who deals, in addition to the works, with acquisition policies, as well as the importance of incorporating the work of more recent artists: Gaudier Brzeska, Eric Gill or Stanley Spencer, and not only the of the old masters (1941, p. 56). The contemporaneity with which, in 1966, the board of directors decided to acquire Capillary Action No. 2, 1963, a landscape by James Rosenquist, is an example of such practices; or the importance of internationality in the choice of works for the study of originals by students from both sides of the Atlantic, who address the thinking of artists (1941, p. 50). Likewise, the convenience of acquiring less expensive drawings, but which cover the study areas, is mentioned.

The National Gallery of Canada’s exhibition may include work by modern and post-modern artists of international stature and with an emphasis on multiculturalism and immigrant cultures in their territory. I have already mentioned some examples, but it is possible to highlight the presence of modern landscape work by artists, for the most part, Canadian, such as Landscape, 1940, by Emily Carr; or international acquisitions, such as Lake George with Crows, 1921, by Georgia O’Keeffe; Umbrian Landscape, 1952, by Paul Strand, or current art, such as Lilies, 2000, by Gerhard Richter; Alexanderplatz, 2001, by Robin Collyer, or indigenous art, Fantasy Landscape, 2007-2008, by Shuvinai Ashoona.

Conclusions

The main aspects discussed in this work are the visibility of landscape art in modernity and after modernity, when fundamentally an epistemic and paradigmatic change occurs in the visual arts, of which the landscape is a fragment. The diverse visual Gestalten that expose new shared paradigms remain hidden-or partially hidden-from the visuality of those who did not theorize, or did not completely theorize, the knowable of the visual arts since the revolutionary change, which happened mainly between 1907 and 1915, and which it constituted a phenomenon incompatible with artistic conceptions prior to Fauvism.

This academic report also deals, in accordance with Kuhn’s structuralism, with how museums are guided by paradigms, and must be predisposed to change in order to make visible images of their different systems in this regard. In this sense, this study emphasizes the importance of displaying the works in collection catalogs -formed with curatorial methods-, in addition to the records of international national museums, museums of modern and contemporary art, museums dedicated to landscape art, museums of artists, museums made by artists, of reasoned catalogs, of exhibition catalogs, among others, that allow analyzing images. This research is inclined to study cross-sectionally the collections of museums, whose different conceptions of the world tend to the merging of cultures and globalization as well as the study of the contemporary and the historical, and also favor the exchange of information and those that give way to the migrations, and those who encourage research, discovery and theorizing.

In this itinerary it is essential to keep in mind the component of the object of study in agreement with the artistic community, according to the exceptional sense of our being in the landscape, of our being able to proceed smoothly from the visual foreground to the distance, as worked by Kenneth Clark, as I mentioned before. This work has also sustained the semantic question through the term landscape or the terms associated with it, such as Atlas eclipticalis or Moonscape, from which I have conjectured, based on evidence found in the collections of the national museums of North America, and parallel to visuality, a theory of landscape.

REFERENCES

Albers, J. (ca. 1940). Study for Tenayuca [dibujo, lápiz sobre papel]. The Joseph & Anni Albers Foundation. https://albersfoundation.org/art/josef-albers/drawings/#slide12 [ Links ]

Anselmo, G. (1965-2000). La mia ombra verso l’infinito della cima dello Stromboli durante l’alba del 16/8/65/ (Study F) [lápiz en papel impreso] New York Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/95392?artist_id=8211&page=1&sov_referrer=artist [ Links ]

Arnheim, R. (1981). Arte y percepción visual. Alianza Forma. [ Links ]

Belting, H. (1987). The End of the History of Art? University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Belting, H. (2003). Historia del arte después de la modernidad. Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Beuys, J. (1997). Joseph Beuys-7 000 Oaks. En L. Domizio De Durini, The Felt Hat: Joseph Beuys, A Life Told (pp. 191-197). Charta. [ Links ]

Boetti, A. (1976-1982). The Thousand Longest Rivers in the World [bordado en lino y algodón]. Museum of Modern Art/Artists Rights Society/Società Italiana degli Autori ed Editori. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/88222?classifications=any&date_begin=Pre-1850&date_end=2021&q=alighiero+boetti&utf8=%E2%9C%93&with_images=1 [ Links ]

Cage, J. (1992). Without Horizon No. 6 [impresión en papel]. The Crown Point Press. https://crownpoint.com/artist/john-cage/#&gid=1&pid=38 [ Links ]

Clark, K. (1991). Landscape into Art. Icon Editions. [ Links ]

Daix, P. y Rosselet, J. (1979). El cubismo de Picasso. Blume. [ Links ]

Danto, A. (1997). After the End of Art. Contemporary Art and the Pale of History. Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Debray, R. (2000). Vida y muerte de la imagen. Historia de la mirada en Occidente. Paidós. [ Links ]

Duchamp, M. (1913). Erratum Musical. En A. D’Harnoncourt & K. McShine, Marcel Duchamp (p. 264). The Museum of Modern Art/Philadelphia Museum of Art. [ Links ]

Duchamp, M. (1949). 50 cc of Air de Paris [ámpula de vidrio]. Philadelphia Museum of Art. https://philamuseum.org/collection/object/51628 [ Links ]

Ellkins, J. (2013). Theorizing Visual Studies. Routledge. [ Links ]

Fischer, H. (1981). L’Histoire de l’art est terminée. Balland. [ Links ]

Foucault, M. (1981). Esto no es una pipa. Ensayo sobre Magritte. Anagrama. [ Links ]

Fulton, H. (1971). The Pilgrims Way. Tate Modern. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/fulton-the-pilgrims-way-t07995. [ Links ]

Government of Canada. (1990). Museums Act [Justice Laws Website Home]. https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/m-13.4/index.html [ Links ]

Grasskamp, W., Nesbit, M. y Bird, J. (2004). Hans Haacke. Phaidon. [ Links ]

Gris, J. (1915). Ace of Clubs and Four Diamonds [óleo sobre tela]. National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.163527.html [ Links ]

Hockney, D. (2012). First edition for a tv screen [videoinstalación]. David Hockney [página web del artista]. https://www.hockney.com/works/digital/movies [ Links ]

Joosten, J. (1998). II Catalogue Raisonne of the Work of 1911-1944. Harry N. Abrams. [ Links ]

Kandinsky, V. (1994). Reminiscences/Three Pictures. En K. Lindsay & P. Vergo, Kandinsky. Complete Writings on Art (pp. 355-391). Da Capo Press. [ Links ]

Klee, P. (1919). Wald Bau [pintura]. Museo del Novecento [página web del museo]. https://www.museodelnovecento.org/it/collezione?in-10-capolavori?paul-klee [ Links ]

Kuhn, T. (1958). Comment on the Relations of Science and Art. En T. Kuhn, The Essential Tension. Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change (pp. 340-351). University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Kuhn, T. (1995). La estructura de las revoluciones científicas. Siglo XXI Editores. [ Links ]

Kuhn, T. (1996). ¿Qué son las revoluciones científicas? y otros ensayos. Paidós. [ Links ]

Lichtenstein, R. (1967). Ten Landscapes. Modern Museum of Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78196?classifications=any&date_begin=Pre-1850&date_end=2021&q=Roy+Lichtenstein&utf8=%E2%9C%93&with_images=1 [ Links ]

Long, R. (1974). A Straight Hundred Mile Walk on the Canadian Prairie [fotografía]. National Gallery of Canada. https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/a-straight-hundred-mile-walk-on-the-canadian-prairie [ Links ]

Lugo, A. (1933). Paisaje de Taxco-La aduana [linóleo]. Museo Nacional de Arte, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes [INBA], Donación al INBA, 1999. http://munal.emuseum.com/objects/2678/paisaje-de-taxco--la-aduana?ctx=826ecde7-2411-45bf-8207-09da9628a411&idx=23 [ Links ]

Magritte, R. (1927). Die schnelle Hoffnung (L’espoir rapide). Hamburger Kunsthalle. https://online-sammlung.hamburger-kunsthalle.de/de/objekt/HK-5156/die-schnelle-hoffnung-l´espoir-rapide?term=&filter%5Bobj_actuallocation_s%5D%5B0%5D=Klassische%20Moderne&start=80&context=default&position=88 [ Links ]

Manovich, L. y Sunley, J. (2021). Museum of Pictorial Culture. From Less-Known Russian Avant-garde series. Tangible Territory Journal. [ Links ]

Modotti, T. (ca. 1925). Líneas de teléfonos [impresión de negativo, plata sobre gelatina]. Museo Nacional de Arte. http://munal.emuseum.com/objects/2293/lineas-de-telefonos-impresion-de-negativo-original-del-comi?ctx=494dda2d-9af2-414f-91d7-ce8b216c495f&idx=248 [ Links ]

Mondrian, P. (1915). Compositie 10 in Zwart Wit [óleo sobre tela]. Kröller Müller. https://krollermuller.nl/en/piet-mondriaan-composition-10-in-black-and-white [ Links ]

Munal. (7 de septiembre de 2017). La colección del Museo Nacional de Arte ahora en línea [boletín 215]. Gobierno de México, Secretaría de Cultura. https://inba.gob.mx/prensa/6864/la-coleccion-del-museo-nacional-de-arte-ahora-en-linea [ Links ]

Museo del Novecento. (2022). Museo del Novecento [página web del museo]. https://www.museodelnovecento.org/it/collezione [ Links ]

Museo Nacional de Arte. (s. f.). Visitas guiadas [página web del museo]. http://www.munal.mx/en/visita [ Links ]

Musée de L’Homme. (20 de diciembre de 2020). Vénus de Lespugue. https://www.museedelhomme.fr/fr/resultats-de-la-recherche?search_api_fulltext=Vénus+de+Lespugue [ Links ]

Museu Picasso. (30 de diciembre de 2020). Exposiciones [página web]. Ayuntament de Barcelona. http://www.bcn.cat/museupicasso/es/exposiciones/90-98.html [ Links ]

Musée Picasso Paris. (2022). Musée Picasso Paris [página web del museo]. https://www.museepicassoparis.fr [ Links ]

National Gallery of Art. (2020a). Collection [página web]. https://www.nga.gov/collection/collection-search.html [ Links ]

National Gallery of Art. (2020b). Mission, vision, values [página web]. National Gallery of Art. https://www.nga.gov/about/mission-vision-values.html [ Links ]

National Gallery of Canada. (2021). Mission Statement [página web]. National Gallery of Canada. https://www.gallery.ca/about/mission-statement [ Links ]

Nessen, S. (1993). Multiculturalism in the Americas. Art Journal, 86-91. [ Links ]

Object ID. (Mayo de 2021). Museum. International Council of Museums. https://icom.museum/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/ObjectID_spanish.pdf [ Links ]

Oppé, P. (1941). Drawings at the National Gallery of Canada. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 50-56 [ Links ]

Orozco, C. (1938). Paisaje nocturno [punta seca]. Museo Nacional de Arte, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Acervo Constitutivo, 1982. http://munal.emuseum.com/objects/3556/paisaje-nocturno?ctx=ed6379e7-1fa6-414f-b013-802dfe9d1577&idx=95 [ Links ]

Photoplay. Obras de The Chase Manhattan Collection. (1993). Photoplay. Obras de The Chase Manhattan Collection. The Chase Manhattan Corporation. [ Links ]

Picasso, P. (junio-julio, 1907). Paysage lié aux “Moissonneurs”: arbres. Musée Picasso Paris. https://www.museepicassoparis.fr/fr/collection-en-ligne#/artwork/160000000001380 [ Links ]

Picasso, P. (1909). The Reservoir, Horta de Ebro, Horta de Sant Joan [óleo sobre tela]. Museum of Art Modern. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78718 [ Links ]

Rabadán, M. E. (2015). Contrapunto de teorías del conocimiento en la obra de Piet Mondrian. En T. Torres, Estado del arte (pp. 87-108). Universidad de Guanajuato. [ Links ]

Rabadán, M. E. (2017). La estructura de las revoluciones científicas según Thomas Kuhn en el análisis de la historia del arte. Arbor, 193(783): a372. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/arbor.2017.783n1003 [ Links ]

Richter, G. (1941). The New National Gallery in Washington. The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 174-183. [ Links ]

Rivera, D. (1910). Después de la tormenta [óleo sobre tela]. Museo Nacional de Arte, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Acervo Constitutivo, 1982. http://munal.emuseum.com/objects/119/despues-de-la-tormenta?ctx=db71cbc0-011d-4362-9f3e-5d3f91531bf8&idx=214 [ Links ]

Rivera, D. (1915). Paisaje zapatista [óleo sobre tela]. Obtenido de Museo Nacional de Arte, Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, Acervo Constitutivo, 1982. http://munal.emuseum.com/objects/98/paisaje-zapatista-1915-anverso-la-mujer-del-pozo-1913-?ctx=826ecde7-2411-45bf-8207-09da9628a411&idx=17 [ Links ]

Rosenberg, D. (2004). The Trouble with Timelines. En A. Groom, Time (pp. 60- 62). Whitechapel Gallery/The MIT Press. [ Links ]

Rothko, M. (1944). Landscape [óleo y grafito sobre tela]. National Gallery of Canada. https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.67415.html [ Links ]

Salcedo, D. (2011-2012). A flor de piel [instalación]. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum. https://harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/351354?position=1 [ Links ]

Schmidt-Rottluff, K. (1912). Graue Landschaft. Hamburger Kunsthalle. https://online-sammlung.hamburger-kunsthalle.de/de/objekt/HK-200513/graue-landschaft?term=&filter%5Bobj_actuallocation_s%5D%5B0%5D=Klassische%20Moderne&context=default&position=9 [ Links ]

Shama, S. (1995). Landscape and Memory. Vintage. [ Links ]

Ulrich, H. (2014). Ways of Curating. Penguin Books. [ Links ]

Vattimo, G. (2007). El fin de la modernidad. Nihilismo y hermenéutica en la cultura posmoderna. Gedisa. [ Links ]

Volume Information. (1941). The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, 205-206. [ Links ]

1Editorial translation. All quotes and description of terms where the original text is in Spanish or other languages are also editorial translations.

2Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger explain in Du Cubism (1912) the change, as they experience their relationship with the work as a reality different from nature, in the form of knowledge, abstract, in this case, entirely different from what the artist prior to cubism could obtain: “There is no direct way of valuing the processes thanks to which the relationships between the world and thought become perceptible to us. What is commonly invoked, finding in a painting the familiar motivating features of form, proves nothing at all. Let us imagine a landscape. The width of the river, the thickness of the foliage, the height of the banks, the dimensions of each object and the relations between such dimensions are certain guarantees. Good; if we find them intact on the canvas we will not have learned anything about the talent or genius of the painter. The river, the foliage, and the banks, despite a careful representation of their proportions, no longer say anything about their width, thickness and height, nor about the relationships between those dimensions. Removing all this from its natural space, they have become part of another kind of space, which does not assimilate the observed proportions. They are something external. They have the same importance as a catalog number, as a title at the bottom of a painting. To discuss this is to deny the space of the painter; it is to deny painting itself” (Gleizes & Metzinger, 1912, p. 231).

3The Gestalt theory understands in a holistic way the perception of the total system of the image—that is to say that the sum of the parts does not equal the total scheme—in the same sense in which psychology works. The mind, for its part, always functions, in Rudolf Arnheim’s terms, as a whole (Arnheim, 1981, pp. 17-18). Furthermore, according to Thomas Kuhn, Gestalt changes—a comprehensive system of the image—in the scientific community respond to theoretical changes; scientists see the known universe in an entirely new way, due to theoretical/paradigmatic changes (1995, p. 176).

4Another part of this research deals with examples from the 1922 Piet Mondrian retrospective at Herber Henkels, commented on by Herman Hana; the exhibitions Piet Mondrian and The Hague School of Landscape Painting (1969), Norman Mackenzie Art Gallery and Edmonton Art Gallery, and Piet Mondrian (1995), Haas Gemeentemuseum and Museum of Modern Art in New York as they were worked on by different teams of curators specialized in the work before and after the revolutionary change of 1907. This segment analyzes, according to Kuhn’s model, how in order to visualize the work it is essential to assimilate the discoveries of the paradigmatic change (Rabadán, 1915, pp. 87-108).

5The art of modernity and after modernity are terms that comes from visual arts studies to talk about theories, models or paradigms. The artistic community discusses the art of modernity and after modernity or, as Gianni Vattimo put it, not in an exact sense according to Hegel, but in a “strangely perverted” one according to Theodor Adorno, as an overcoming of the aesthetic in the historical avant-gardes, instead integrating practical cognitive possibilities that can be examined, and he adds that they can outline what is to come. The feasible practical cognitive possibilities to examine are conceptual art, as I have just evidenced in the testimony of Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger, in their text Du Cubism. When Vattimo adds the idea that they can outline what is to come, he is referring to the articulation of a new paradigm (Vattimo, 2007, p. 49). The concept of death or the end of art according to Hegel permeates the argumentation of both the Italian philosopher and Arthur Danto, who sees the main change, of an equally paradigmatic nature, although towards the end of art in 1964 in the United States of America and during the rise of pop art (1997, pp. 25-41), while Hans Belting acknowledges multiple reasons why art history as a whole rejects modern art, beginning with the actions and abstractions in the work of Marcel Duchamp, when it also corresponds to the history of art to analyze those irreconcilable practices with the previous ones (Belting, 1987, p. 34). However, this study starts from concrete facts, which are the works of art, in an artistic community in French, German, and Dutch European cities; for example, that of those who between 1907 and 1915 changed their visual Gestalt, which, it suggests, responds to the articulation of a completely new conception of art, of initial examples of conceptual, abstract, naturalistic art and in such possible combinations that they make them be pieces contrary to the previous art. Those initial works, of a revolutionary nature, which fail to add knowledge to what was already known about painting, will be what guides the paradigmatic examples of artists who have worked on their works throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, as dealt with in this academic report.

6The temporality of the avant-garde conception of the history of art in the academic texts in which we have been trained has been adjusted to a chronological chart and has not foreseen paradigmatic changes—revolutionary and normal—. These chronological charts embody a conception of time dated to 1753 (Rosenberg, 2004), that is, more than a century and a half before the ready-mades.

7There is a difference of 45 in the numbers, between the total and the segments, which is the responsibility of the Museum to explain. The contradiction, however, allows us to see and compare the volumes of acquisitions.

8The checklist for Object ID includes: 1) Taking pictures. 2) General questions: type of object, what kind of object is it (e.g.: painting, sculpture, clock, mineral); materials and techniques (wood, bronze…). Production method (carved, modeled, etched…). Numerical inscriptions. Characteristics that distinguish it. Title, subject, what does it represent (eg, landscape, bottle, woman with nymph?), date or period, author. 3) Write a short description. 4) Keep it in a safe place. (cf. Object ID, 2021).

9Zapatista Landscape, 1915, by Diego Rivera, has been studied and published on several occasions, such as in Susan Nessen’s Multiculturalism in the Americas(1993, p. 87).

10On the Museum’s platform there is the guide to the exhibition of José María Velasco and the landscape that he analyzes, by thematic groups, is the one recorded in the formation of the nation: traveling artists who arrived in Mexico, Landesio initiates the genre, landscape and perspective in San Carlos, views of the surroundings, study of nature, constructions made by each artist—they say they were not copies of nature—, skill, Velasco dispenses with human figures, to prioritize nature, notion of progress in the landscape and Víctor Rodríguez, curator of Velasco.

Received: July 19, 2021; Accepted: August 06, 2022; Published: December 28, 2022

texto en

texto en