Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Intervención (México DF)

versão impressa ISSN 2007-249X

Intervención (Méx. DF) vol.13 no.25 México Jan./Jun. 2022 Epub 13-Fev-2023

https://doi.org/10.30763/intervencion.263.v1n25.42.2022

Research articles

Assessing Value of Postizos as a Naturalist Resource of Viceregal Imagery

* Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía (ENCRYM), Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), México. mercedes_murguia_m@encrym.edu.mx

This research article is a reflection on the concept and application of the term postizo in religious sculpture, both in its current valuation as an element that is not part of the sculpting but added, such as the case of glass eyes, hair eyelashes, teeth and nails made from bone-not so the clothing and other elements, such as bases or crowns-. All this implies that restorers in training frequently question the role that this element play’s in the piece’s creation. For the above, it is why in this text I propose that postizos should be conceived as an integral part of the statue’s creation process, being a recurring resource, which provides greater realism, complementing the woodwork, regardless of the materials that must be “added”. To support this proposal, referential pieces that offer a greater understanding of viceregal imagery will be used as examples.

KEYWORDS: sculpture; polychromy; postizo; added; multi-material; imagery

Este artículo de investigación es una reflexión sobre el concepto y la aplicación del término postizo en la imaginería-escultura religiosa, su valoración actual y su significado como elemento que no es propio de la talla, sino agregado, como es el caso de los ojos de vidrio, pestañas de pelo, dientes y uñas de hueso -no así las vestimentas y otros elementos, como asientos o coronas-; esto implica que los restauradores en formación frecuentemente cuestionen el papel que desempeña este elemento en la manufactura de la obra. Por lo anterior, en este texto propongo que los postizos deben de ser concebidos como parte integral del proceso de creación de una escultura, al ser un recurso recurrente, para dotarla de mayor naturalidad, complementando el trabajo de la madera, no importando los materiales que se requieran “añadir”. Para sustentar esta propuesta se utilizarán ejemplos de piezas referenciales que ofrecen un mejor entendimiento de la imaginería virreinal.

PALABRAS CLAVE: escultura; policromía; postizo; añadido; polimatérico

Introduction

The present work is derived from tutoring experience and the necessary research associated with the teaching of manufacture techniques of religious statues in the fourth semester of the B. A. in Restoration at the Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía (ENCRYM, Mexico). As part of the topics covered, when dealing with the use of postizos1 and other materials to complement the carving, students regularly formulate questions regarding the role each had in the process of conceiving and creating the sculpture. Furthermore, constantly studying the documents generated by interventions carried out on various polychromed sculptures2 to review them in class gives rise to certain reflections regarding said research. Keeping in mind that these pertain to specific moments, one of the main contributions of this exercise is to rethink them and evaluate the concepts and actions surrounding learning and the study of religious sculptures, and thus submit or resubmit lines of investigation that also generate interesting debate among disciplines such as art history and restoration, all of which nourish discussion in the classroom.3

Different views from scientific bibliography and questioning them

In the series of questions that arose from reviewing other work to put forward this research article, the topic of the concept of sculpture is fundamental. The Real Academia de la Lengua Española (RAE, Royal Academy of the Spanish Language) dictionary indicates that sculpture is the art of modeling, carving, or sculpting three-dimensional figures in certain materials (Diccionario de la Lengua Española [DLE], 2021a). If we take this definition to the technical domain, to achieve this tridimensional effect material is usually removed, not added. Starting from this premise, in his chapter on Buonarroti, Cellini, and Vasari, Rudolf Wittkower points out that when the former was asked about the comparison between painting and sculpture, he stated that “I understand sculpture to be that which is done by means through removing (per forza di levare), whereas that which is made by adding (per via di porre that is to say, to mode) is more similar to painting” (Wittkower, 1980 [1971], p. 145)4. Along those lines, this researcher retrieves what Alberti had said when noting a similar difference between modeling and sculpting, adding Da Vinci’s affirmation that “the sculptor always takes material away from the same block” (Wittkower, 1980 [1971], p. 145). So what occurs while forming a polychrome wooden sculpture? Albeit the cited principle applies to carving the wooden support, we can have other added materials, such as pictorial layers, which are not postizos. What concept should this term, therefore, be held to? I thus find it fundamental that we reflect on something that is more than an addition, whose use should have been conceived as an integral part when devising the process to create the polychrome sculpture. Hence, it is important to ponder the different re sources associated directly with the representation of human anatomy, which in addition to conveying various intentions the artist wishes to manifest, such as movement, volumes, bleeding, or feelings, to make the work more natural, regardless of the material employed.5

While carrying out the necessary review of other notable texts that focus on artistic techniques, particularly those regarding wooden sculpture, I noted a clear lack of consideration regarding the postizo, and when it is mentioned, it is done so indistinctly for wigs, teeth, nails, eyelashes, and ribs (Gañán, 1999; Maquivar 1999).6 There is a clear association between these elements and parts of the body which, being made from a different material than the main support, are directly referred to as additions since they are not part of the carving. On that note, others even include under that same heading the clothes, attributes, and ornaments-in cases where these form part of the sculptural form-for being of a different material to the main wooden support. However, I do not find this relevant,7 making it necessary to reflect on the difference between additions and postizos, since the latter were made ex profeso and practically always formed part of the processes to conceive and manufacture polychrome wooden sculptures.

On the subject, I sustain that the use of “other complementary materials”-as they are commonly referred to (Maquívar, 1999, p. 68-69)-constitutes the start of interaction within a system of construction and can appear in any of the various creative processes if the artist so chooses. Similarly to the tongues and teeth on many effigies, the glass eyes are set and placed inside the face in the first procedures to form the carving. Following this, cords can be used to generate the volume of veins at the time primers are applied, as well as cork, cloth, or bones, to offer greater veracity or emphasize certain points of attention, such as wounds or exposed ribs. After the polychroming, this constructive system sometimes concludes with tears rolling down the cheeks of virgins or saints, as well as eyelashes. Since the woodwork is prioritized, these materials “additions”-postizos-are left as being secondary, despite being a recurring sculptural resource.

In light of this, it is important to stress the need to change the current concept of the process of creating a sculptural piece that goes from placing the order up to delivery, in which the postizos are not accessories but, rather, elements that are inherent to its concept and creation.

It is not my intention to question the term postizo-“That is not natural or proper to, but rather added, imitated, feigned, or overlayed” (DLE, 2021b)- adopted as the description of the manufacture of sculpture since, by definition, it is added material of a different nature to the carved one. But, indeed, I differ in the connotation that has labeled it as a “finishing” technical resource, or as a simple posterior complement to the concept of working the wood, leaving it on a secondary plane, isolated even, anecdotal. Because this concept originated in the bibliography of disciplines such as fine arts/visual arts8 or developed within an aesthetic tradition of art history,9 it is noteworthy that in polychrome sculpture there is a manifest devaluing of both the use of different sculptural resources as well as the nature of said materials, resorting to terminology born of traditional use; for example, cristal eyes and certain tears, which are made of glass.

Without abandoning the definition of postizo provided by RAE (DLE, 2021b), I wish to analyze what Constantino Gañán Medina wrote in his reference manual Técnicas y evolución de la imagi nería polícroma en Sevilla (Techniques and evolution of polychrome imagery in Seville, 1999), for its echoes on the subject at hand. Chosen for being a reference work, one of the first’s to dedicate a section to the subject, in addition to being a text that has long been used at the encrym Seminario-Taller de Restauración de Escultura Policromada (STREP) (Seminar-Workshop on Restoration of Polychrome Sculpture).

Although the prologue by Gañán Medina-holder of a B.A. in Fine Arts-notes that it is aimed at historians, restorers, sculptors, and creators of religious images, it indicates as a modern antecedent the art historian Domingo C. Sánchez-Mesa Martín volume Técnica de la escultura policromada granadina (Granada polychrome sculpture technique, 1971), whom, being the son of a carver of religious images, had watched and learned the processes followed by such artists in his father’s workshop in Granada after the Civil War10. Keeping in mind that this research took place in the 90s-it was published in 1999-and much has been written about sculpture since, Gañan Medina defines postizos as “additions of a different nature and composition to the work’s base. It does not include robes or jewels […] their use responds to the intention to animate the piece […] whose sculptural representations are harder to achieve” (Gañán, 1999, p. 227). To begin with, I disagree when he says the carver intends to “animate the piece” through the addition of other materials to solve areas that are hard to carve, seeking realism-rather than realism, I would refer to naturalism-,11 since this would match the undermining of craftsmanship, and what we say on either side of the Atlantic, with countless examples, regarding carvings that back our perception.

To continue with the notes, although the use of postizos can be recurrent in sculptors “lacking in technique”, as the author indicates (Gañán, 1999, p. 227), the truth about Hispanic statuary is that even some of its most outstanding carvers used them. On the subject, while reviewing the materials of one of the Spain’s historically most important crucifixes, the 14th century Holy Christ of Burgos located in Burgos Cathedral, we prove that they resorted to diverse materials in order to help make the effigy articulated at the neck, arms, legs, and fingers. Here, the anonymous author resorted to natural hair for the mustache, beard, and hair, but also cowhide to cover the entire piece to hide the joints that help it move, in addition to chopped wool to fill them and horn to form the nails (Martínez, 2003-2004, p. 207-246). Another example is the image of Christ Crucified by Juan de Valmesada (ca. 1487, 1488-1576), an outstanding representative of the school of Castille (Figure 1), located at the top of the main altar of Palencia Cathedral, where certain veins and trickles of blood were made with cords, despite crowning an altar that is 20.5 m high (Figures 2 and 3).12

(Photograph: Ramón Pérez de Castro; courtesy: Ramón Pérez de Castro, 2021)

FIGURE 1 Christ Crucified by Juan de Valmaseda (ca. 1487, 1488-1576). Main altar, Palencia Cathedral, Spain. Detail of veins and blood made with cords.

(Photograph: Ramón Pérez de Castro, 2021; courtesy: Archive of the H. C. of Palencia’s Cathedral, 2022)

FIGURES 2 and 3 Partial view of Christ Crucified by Juan de Valmaseda (ca. 1487, 1488-1576). Main altar, Palencia Cathedral, Spain. Detail of veins and blood made with cords placed below the primer.

Another important case is that of sculptor Gregorio Fernández (1576-1636), also Spanish, among whose outstanding production it is usual to find postizos as a resource that culminates an interesting pairing, composed of the anatomy of the body achieved through working the wood and the materials he uses for effects he wishes to highlight, to achieve greater naturalism. Thus, in several of his statues, such as the Recumbent Christ, now located in the National Museum of Sculpture at Valladolid (ca. 1625-1630)-13 multiple elements come together with the task of carving: placement of crystal eyes, placing of horn nails, use of what appears to be cork to simulate coagulated blood on wounds, and, the cuasi transparency of the painting of the sandal, leaving the wood almost visible, which generates an interesting game of perception (Bray, 2010, p. 166-171).

Thinking of postizos as additions of a substitutionary or secondary character fosters their loss of validity, which demands that studying and valuing them have a correspondence in restoration and art history, to achieve a deeper understanding of the historical circumstances of the moment a sculpture was conceived, its processes and materiality. Particularly in the Hispanic world, sculptors and painters dedicated their greatest talent to portraying sacred figures as naturally as possible and hence, close to the worshiping spectator. They did not hesitate, according to the subject, to make them emaciated, crude, austere, and often even bloody, for their intention was “to shake the senses and move the disposition, as a means to propagate the faith” (González y Caballero, 2010, p. 4). All of this stood out and was one of the arguments behind the exhibition Lo sagrado hecho real. Pintura y escultura españolas, 1600-1700 (González y Caballero, 2010), which expressed valuing postizos as a unique resource to achieve said intentions. The exhibition catalog makes an important point on the frontiers that separate illusion from reality in a specific context, explaining how, to foster spreading the faith, sculptors and painters combined abilities with the aim to portray the great Christian stories with astonishing “realism”, using different and ingenious technical solutions in materiality, resulting in an art that is “sensual, brilliant” and “complex” (Bray, 2010, p. 15-43).

A case from new Spain to ponder

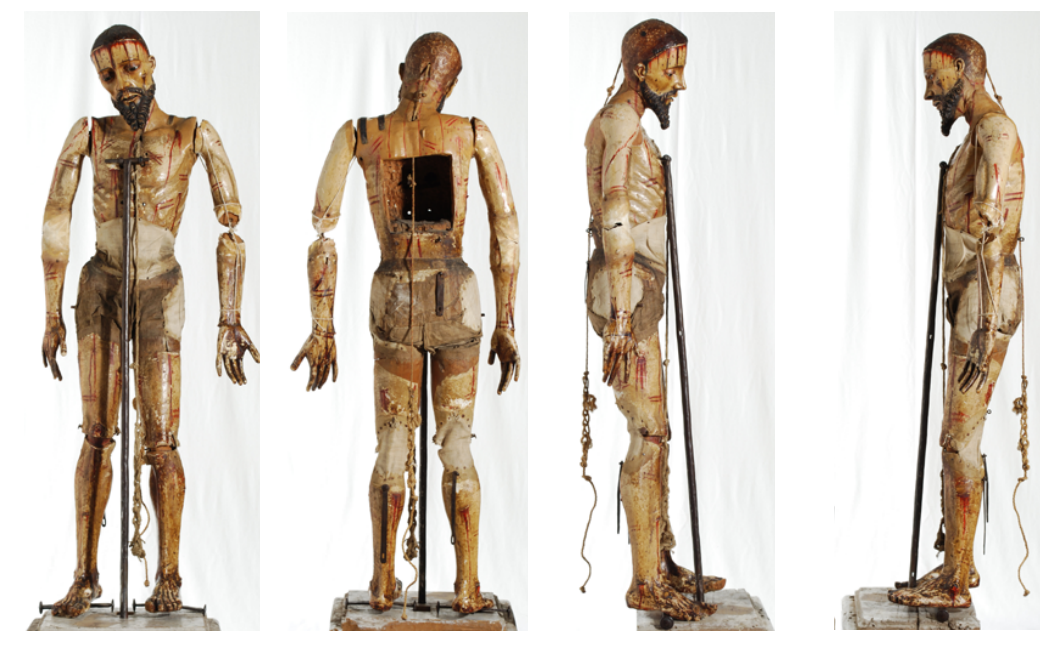

In line with the considerations expressed at the beginning of this work and to refer to a close example, conditioned by the space I am limited to, I shall bring up a significant case from what was once New Spain which gathers various elements analyzed herein. Furthermore, although we have worked on some 85 sculptures with postizos, I find it relevant to include this case since it offers, in a general manner, the way postizos have been broached over the years during the process of training students.14 It is an articulated image that represents Jesus of Nazareth carrying the cross, which is held in Ozumba, in the state of Mexico that was restored in 2010 in the STREP-ENCRYM.

The piece corresponds to an effigy of Christ carved in ayacahuite pine (Pinus ayacahuite sp.),15 with articulations in the neck, stomach and hips, arms, and legs; during processions, it represents at least five Stations of the Cross.16 It is therefore known as El Señor de las tres caídas (The Lord of the Three Falls) (Figure 4); it has been suggested that it was probably created in the late 17th or early 18th century.

(Photograph: Isis Gutiérrez Olguín, Sandra Martínez Pérez, Alejandra Mejía Zavala and Naitzá Santiago Gómez; courtesy: STREP-ENCRYM-INAH, 2010)

FIGURE 4 The Lord of the Three Falls. General views undressed before the process.

Its structure, its core comprises 31 fragments joined together with glue or by employing hinges. Metal elements were placed inside certain sections, which join them together while allowing movement, then covered with thin leather to integrate them, thus simulating Christ’s skin. It also has iron nails holding down the cloths and cast iron tacks in the hips, face and behind the knees (Figure 5).

(Scheme: Isis Gutiérrez Olguín, Sandra Martínez Pérez, Alejandra Mejía Zavala and Naitzá Santiago Gómez, 2010)

FIGURE 5 The Lord of The Three Falls. Technique to manufacture the support. Restoration Report, STREP-ENCRYM-INAH, 2010.

Another noteworthy element is that after it was carved, cords were placed to create the lifted veins17 and emphasize the wounds (Figure 6). I will not linger here explaining the subsequent pro cesses to paint the flesh since the analysis carried out did not reflect any particular data differing from the usual way these sculptures are polychromed.

(Photograph: Isis Gutiérrez Olguín, Sandra Martínez Pérez, Alejandra Mejía Zavala and Naitzá Santiago Gómez; courtesy: STREP-ENCRYM-INAH, 2010)

FIGURE 6 The Lord of The Three Falls. Anchoring orifice to hold up the hand; detail of wounds and veins on the left hand.

In both the intervention report (Gutiérrez et al., 2010) and a publication by some teachers from this academic institution (Murguía & Unikel, 2014, p. 207-259), the following were indicated as postizos: the eyelashes made of hair held between two strips of paper and glued to the upper eyelid18-which matches that indicated in the bibliography (Gañán, 1999, p. 231)-as well as the wig. Following a radiological analysis, we know that the eyes are made of glass and pot-shaped, that is to say, they were made with a thin vitreous sheet that was given a concave shape with the help of a mold or appropriate surface.19 These pieces are painted on the back side, where the brushstrokes are visible20 (Figure 7). In addition, they have-the report also indicated them as additions (Gutiérrez et al., 2010)-teeth made of bone on both mandibles, which were carved separately and encrusted one by one on the support.

(Photograph: Isis Gutiérrez Olguín, Sandra Martínez Pérez, Alejandra Mejía Zavala and Naitzá Santiago Gómez; courtesy: STREP-ENCRYM-INAH, 2010)

FIGURE 7 The Lord of The Three Falls. Insertion of eyes and teeth during the carving process.

I will not dwell on the mechanism’s technology for the object of our study, since I am particularly interested in stressing how postizos were approached and considered at the time of the intervention (ENCRYM-INAH, 2010). Albeit the technique to manufacture the leather in the joints was explained and referred to as postizos, in the section regarding “material condition report” they are mentioned as part of the support, and their state of conservation is omitted. However, they are a clear example of the intention to make the sculpture mobile, which can only be achieved by placing different materials, fragments of skin, or stuffed cloth. Linked to this, the cords to highlight veins and glued cloths-named thus in the text, as mentioned, regarding those soaked in the glue that emphasize wounds and worked from apparel-would also constitute elements used to accentuate the expression, which functions not just as additions but also as sculptural resources.

Along with these new visions, and from the point of view of a restorer, I find it necessary to refer here the term multi-material21. In his 2017 article Vestidas y de pasta: testimonios documentales sobre escultura procesional para la Cofradía de la Soledad de Madrid en el siglo XVI (Dressed and Pasta: Documentary Testimonies on Processional Sculpture for the Brotherhood of Solitude of Madrid in the 16th century), Manuel Arias noted the importance of multi-material in Spanish sculpture, to mark the need to investigate them systematically and generally, with transversal studies, manifesting the information conceived by the restoration and as part of a more active process of collaboration. Arias stated that the diversity of materials provides greater veracity and that beyond the perpetual image, it pursues the emulation of reality (Arias, 2017, p. 119). Thus he insists that devotional sculpture has used different materials to create it, historically resorting to different supports, such as wood, paper, papier maché, corn stalks, and the so called glued cloths, to name some of the most important.

Returning to the El Señor de las tres caídas from Ozumba, studying it and understanding its character as a multi-material sculpture-as an interesting example of the many the strep has worked on over more than 20 years-enriches our appreciation of it and, hence, points out the importance of turning our gaze to the integral perception restorers have of pieces and, thus, to the sum of their elements. On the other hand, it is necessary to bring back the term addition which, as mentioned throughout, refers to elements such as crystal eyes, skins, or teeth made of bone that are an indivisible part of the piece, as a basis from which I propose the first dissertation as a preamble to future studies in greater depth.

A sort of conclusion to these first views

In light of the above, we can clarify that the various materials associated with forming a sculpture and those that differ from the main support, such as postizos, are intrinsic to them and should be understood as part of a whole from the sculptor’s intentions. Furthermore, those placing the order should be considered, without forgetting the customer’s possible preferences for the craftsmanship such additions provided.

It is necessary to distinguish those diverse postizo materials in sculpture from other elements or attributes of the images, such as jewelry, crosses, halos, crowns, stands, or bases, for although these form part of the global understanding of the piece, they serve as iconographic elements that are not postizos in the sculptural sense and most cases go changing over time, these could be called complementary elements or other elements. As for the outfits for clothed or candelstick statues, although they can be made from different materials, they should not be classified as postizos, as García Medina says since their intention is none other than that: dressing them. It is important to mention this because although it might seem obvious that clothing aims to dress, the discussion becomes more complex when understanding the function of glued cloths where there is no sculpted body, and how the future restorer conceptualizes it while becoming familiar with the study of religious statues.

Finally, what I have sought in this brief research, derived from that conference which led me to rethink the subject of postizos, is the necessity to revise terms and concepts, that we discuss them and value them as an interdisciplinary part and the link to art history and restoration, which should occur when the next pages on the material history of sculpture are written.

REFERENCES

Arias, M. (2017). Vestidas y de pasta: testimonios documentales sobre escultura procesional para la Cofradía de la Soledad de Madrid en el siglo XVI. En R. M. Román (Coord.). Escultura ligera. Jornadas Internacionales de Escultura Ligera. Ayuntamiento de Valencia, 119-113. [ Links ]

Bray, X. (2010). Lo sagrado hecho real: pintura y escultura española, 1600-1700. Ministerio de Cultura, Museo Nacional Colegio de San Gregorio, Valladolid (5 de julio-30 de septiembre), 15-43. [ Links ]

Casciaro, R. (2008). La scultura in cartapesta. Sansovino, Bernini e i maestro leccesi tra tecnica e artificio. [Catálogo de la muestra.] [ Links ]

Casciaro, R. (2012). Cartapesta e scultura polimaterica. Università del Salento. [ Links ]

Cofradía del Huerto. (2022 [1983]). Autobiografía de don Domingo C. Sánchez Mesa. https://hermandadelhuertogranada.com/autobiografia-de-don-domingo-c-sanchez-mesa [ Links ]

Diccionario de autoridades. (1726-1739 [1737]). Postizo, t. V. Real Academia Española. https://apps2.rae.es/DA.html [ Links ]

Diccionario de la lengua española. (2021a). Escultura, 23.ª ed. Real Academia Española. https://dle.rae.es/escultura [ Links ]

Diccionario de la lengua española. (2021b). Postizo. Real Academia Española. https://dle.rae.es/postizo [ Links ]

Gañán, C. (1999). Técnicas y evolución de la imaginería polícroma en Sevilla. Universidad de Sevilla. [ Links ]

Giubbini, G. y Sborgi, F. (1999 [1973]). Escultura. En M. Conrado (Coord.), Las técnicas artísticas (Versión española José Miguel Morán y María de los Santos García), 10.ª ed. Cátedra (Manuales de Arte). [ Links ]

González, G. y Caballero, L. (Coords.). (2010). Lo sagrado hecho real: pintura y escultura españolas, 1600-1700. [Catálogo de exposición]. Del 6 de julio al 30 de septiembre de 2010. Museo Nacional Colegio de San Gregorio/Ministerio de Cultura. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, I., Martínez, S., Mejía, A. y Santiago, N. (2010). Informe del proyecto de restauración de la escultura policromada “El Señor de las tres caídas” de la parroquia de la Inmaculada Concepción, Ozumba, estado de México, F. Unikel y M. Murguía (Coords.). Seminario-Taller de Restauración de Escultura Policromada-Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía-Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [ Links ]

Maquívar, M. del C. (1999). El imaginero novohispano y su obra: las esculturas de Tepotzotlán. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [ Links ]

Martin, J. R. (1986). Naturalismo. En Barroco. Xarait (Libros de Arquitectura y Arte), 45-68. [ Links ]

Martínez, M. J. (2003-2004). El Santo Cristo de Burgos y los Cristos Dolorosos Articulados. Boletín del Seminario de Estudios de Arte y Arqueología BSAA. Junta de Castilla y León (69-70), 207-246. [ Links ]

Murguía, M. y Unikel, F. (2014). Vivisección del Señor de las tres caídas. En S. Hernández (Coord.). Ozumba, arte e historia. Secretaría de Educación del Gobierno del Estado de México, 207-259. http://ceape.edomex.gob.mx/content/ozumba-arte-e-historia [ Links ]

Murguía, M. (2021). Otras miradas sobre el Cristo de las tres caídas de Ozumba. Reciprocidad entre la restauración y la historia del arte (Segundo ciclo de conferencias. Seminario de Escultura Virreinal). Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. https://youtu.be/3kPZ0wTK3vQ [ Links ]

Réau, L. (1996-1998). Iconografía del arte cristiano: iconografía de la Biblia, Nuevo Testamento. (Traducción D. Alcoba.), t. 1, vols. 1-2. Ediciones del Serbal, 481 y 486. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Mesa, D. (1971). Técnica de la escultura policromada granadina. Universidad de Granada (Colección Monográfica, 13). [ Links ]

Wittkower, R. (1980 [1971]). La escultura. Procesos y principios (Versión castellana Fernando Villaverde). Alianza. [ Links ]

1T.’s N.: In Spanish, the term postizo refers to a corporeal element that is added onto the natural one to give it a different appearance, that substitutes or replaces its absence. Since English lacks an appropriate translation, throughout this text the original term in Spanish will be used.

3As part of the social distancing activities carried out by the Seminario de Escultura Virreinal (Viceregal Sculpture Seminar [SEV]) within the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas (IIE) at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) in the framework of their second cycle of conferences: Reciprocidad entre la restauración y la historia del arte (Reciprocity between restoration and art history, October 2020-February 2021), which I coordinated, where I presented Otras miradas sobre el Cristo de las tres caídas de Ozumba (Other Views On the Christ of the Three Falls from Ozumba; Murguía, 2021), a conference which contains a series of reflections on what should be the indivisible relations between those disciplines and, hence, the association of new points of view surrounding premises and queries which in this case emanate from our object of study, the polychrome sculpture and, particularly, the role postizos play in it. Pablo F. Amador Marrero and Mercedes Murguía Meca were responsible for this project, with the support of Claudia Alejandra Garza Villegas. The conference can be viewed on the Seminario de Escultura Virreinal (2021) YouTube channel.

4Editorial translation. All quotes and descriptions of terms where the original text is in Spanish are also editorial translations.

5I thank doctors Manuel Arias Martínez, Carlos Rodríguez Morales, and Pablo F. Amador Marrero for the discussion on the subject.

6There is ample documentation on the subject in: ENCRYM-INAH restoration reports which can be consulted in the Library and Documentation Center, exhibition catalogs (Bray, 2010, p. 15-43), or publications on polychrome sculpture.

7Following this position on our topic of reflection, clothing cannot be linked to this terminology, since they are additions foreign to the sculpting work, in addition to being subject to changes in taste, periods, or fashions.

8For example, Giubbini y Sborgi (1999 [1973]), in their chapter “Escultura”, Las técnicas artísticas (“Sculpture”, Artistic techniques).

9To mention some: Bray (2010) en Lo sagrado hecho real: pintura y escultura española 1600-1700 (The sacred made real: Spanish painting and sculpture 1600-1700); Gañán (1999) in Técnicas y evolución de la imaginería polícroma en Sevilla; Maquívar (1999) in El imaginero novohispano y su obra: las esculturas de Tepotzotlán (The Novohispanic image maker and his work: the sculptures of Tepotzotlán); Sánchez-Mesa (1971) in Técnica de la escultura policromada granadina (Granada polychrome sculpture technique); in addition to other examples I refer to in other sections.

10I refer to Domingo C. Sánchez-Mesa (Granada, 1903-1989), whose autobiography is located in the Cofradía del Huerto (2022 [1983]).

11As Paula Mues points out in the subjects she teaches at the strep and in history advisory sessions, it is not pertinent to speak of realism because this term is used to denote an artistic and literary movement between 1840 and 1880, so using it in relation to artistic objects prior to that date is an anachronism (personal communication, August 2022). On the other hand, most Spanish publications tend to use the term indistinctly; we see an example in Bray (2010), while John Rupert Martin’s second chapter of Baroque (1986, p. 45-68) dedicates a space to speak about naturalism and its application; hence the use of this term in this work.

12My thanks to doctor Ramón Pérez de Castro for kindly providing these photographs and to the archive of the H. C. of Palencia’s Cathedral.

13Museo del Prado, Madrid, inventory number E-576. On deposit in the Museo Nacional de Escultura, Valladolid, inventory number DE0036.

14Out of a total of 253 sculptures, 85 have presented postizos. The most frequent has been glass eyes and bones incrusted on ribs and teeth. STREP-ENCRYM-INAH database.

15Identification of organic material by ©Leica DFC280 optic microscope and photographs taken with Canon Power Shot S50 camera using a Carl Zeiss ICS Standard 25 adaptor, performed by biologists master Gabriela Cruz and master Irais Velasco on January 27, 2010, in the ENCRYM Biology Laboratory.

16The First Fall, Simon of Cyrene Helps Carry the Cross, Veronica Wipes the Face of Jesus, Second Fall, and Third Fall (Réau, 1996, p. 481 y 484).

17At the time they were named glued cloths. However, this term refers to a different type of constructive technique for statues that involves molding cloth soaked in animal glue.

18These hairs are probably of horsetail, identified as fiber by ©Leica DFC280 optic microscope and photographs taken with Canon Power Shot S50 camera using a Carl Zeiss ICS Standard 25 adaptor, performed by biologists master Gabriela Cruz and master Irais Velasco on January 27 2010 in the ENCRYM Biology Laboratory.

19The radiological studies were performed by doctor Josefina Bautista at the ENCRYM-INAH Radiological Laboratory using a portable Philips Practix 33 in January 2010.

21The term multi-material, began to be used in 2008 as part of Casciaro’s work studying the famous Cartapesta e scultura polimaterica (Casciaro, 2008 y 2012).

BAND. Dead Christ. Altar of the Passion, Rosario Chapel, Santo Domingo, San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas, Mexico. Polychrome articulated image with hair and beard, with teeth added during the carving process (Photograph: Mercedes Murguía Meca; courtesy: Área de Conservación del Centro INAH Chiapas, 2022).

Received: January 20, 2022; Accepted: August 24, 2022; Published: December 28, 2022

texto em

texto em