Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Intervención (México DF)

versão impressa ISSN 2007-249X

Intervención (Méx. DF) vol.13 no.25 México Jan./Jun. 2022 Epub 13-Fev-2023

https://doi.org/10.30763/intervencion.261.v1n25.40.2022

Essay

Analysis of the Methodology for Conservation of Plastic Applied in Contemporary Works of Art

* Dirección General del Patrimonio Universitario (DGPU), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), México, k4rl4jm@gmail.com

Based on the comparative analysis of several case studies related to the application of The Decision-Making Model for the Conservation and Restoration of Modern and Contemporary Art to solve conservation problems of works created with plastic, I propose to delve into the reaches, challenges, implications and results of this subject, since plastic is an industrial material not produced ex profeso for artistic creation which, when used in this field, presents specific characteristics and properties that influence its behavior, deterioration and hence durability. Thus, its ephemeral character makes us question how to conserve such works, where the concept is the most important.

KEYWORDS: plastic; case studies; conservation challenges; research model; degradation

Con base en el análisis comparativo de diversos casos de estudio relativos a la aplicación del Modelo de toma de decisiones para la conservación y restauración de arte moderno y contemporáneo para la solución de problemáticas de conservación de piezas realizadas con plástico, se propone ahondar en los alcances, retos, implicaciones y resultados del tema, pues el plástico es un material industrial no producido ex profeso para la creación artística que, usado en ese campo, reviste características y propiedades particulares que influyen en su comportamiento, en su deterioro y, por lo tanto, en su durabilidad. Su carácter efímero, pues, hace que cuestionemos la manera en que debe conservarse este tipo de obras, en las que lo más importante es el concepto.

PALABRAS CLAVE: plástico; estudios de caso; problemáticas de conservación; modelo de investigación; degradación

Introduction

To begin with, we raise the context of the development and use of plastics in daily life and, subsequently, that of international art creation, with examples of works of art made with these materials, as well as the Mexican context; where the reader is specifically introduced to the work of Emilia Sandoval and her adoption of plastic bags as an expressive material to create the pieces that comprise the series Botánica: nuevas especies (Botany: New Species).

From there we broach our subject with a comparative analysis of the methodology applied to solve problems linked to the conservation of works made of plastic, which includes various examples, concentrating on the piece Tasajo Norstrom.

Context about the use of plastic in everyday life

The great development and industrial-scale production of plastics, in general, have led to what García describes as “daily life in the 20th and 21st centuries was and is significantly influenced by the use of plastics in industrial, domestic and cultural aspects” (2009, p. 28). Said materials:

Represent technological advances and reflect economic history, respectively, for on the one hand they illustrate the large growth in the quantity and types of mediums for information storage, such as payment and credit cards, medical applications and food packaging that allows storage and transport; and on the other hand, the import restrictions on various raw materials, such as rubber, wool and silk to Europe during World War II stimulated the development of synthetic alternatives [Shashoua, 2008, p. 9]1.

Therefore, the use of plastic has been increasingly widespread and has included such a range of human activities that it was in evitable that it also touched the art world.

Introduction to the use of plastic in works of art

In the post war context (the second half of the 20th century) the presence and familiarity of plastic objects favored a change in their valuation: “Going from being a rare substitute material with an aura of exclusivity to being a cheap, commercially mass-produced material, used daily and therefore worthless, losing their reputation as special or valuable materials” (Shashoua, 2008, p. 22). This fostered its use in art in the 20th century which, as Righi notes, “presents great novelties, in fact contemporary art established as an aim the quest for novelty, a criterion foreign to classic or renaissance art, which generated radical changes in artistic creation” (2006, p. 11): artists began to seek new ways of expressing themselves by using industrial materials, based on the increasing globalization.

They recognized particular properties and characteristics in plastics, which allowed them to experiment and innovate, based on the need to find non-traditional materials as a means of expression, along with an exploratory attitude towards the technical possibilities those materials could offer [Chiantore, 1999, p. 1].

The use of plastic in 20th century works of art is the result of the conjunction of technical development and artistic imagination, which furthers experimental practices as a means of expression. Therefore, it has partly been through the materiality of their artistic works made with plastic that the artists were able to transmit the desired concept and meaning, as can be seen in the examples presented below, to mention just a few.

Example 1: “The artist Henry Moore claims materials such as polyester and fiberglass to materialize the irregular, cut, warped sculptural forms of his next work” (Figure 1) (García, 2009, p. 29).

(Photograph: Ron Ellis, September 16, 2007; source: shutterstock.com; stock: 146067593)

FIGURE 1 Henry Moore, Large Reclining Figure, 1984, Kew Gardens, London, UK. Fiberglass sculpture, length 9 m..

Example 2: García mentions is that of Claes Oldenburg, a pi oneer sculptor of pop art,2 who as of 1962 began to create pieces that represented hard objects, but with soft materials (such as fiberglass and polyurethane foam) and on a massive scale (Figure 2) (2009, p. 28).

(Photograph: Cineberg, 2020; courtesy: Cineberg; source: shutterstock.com; stock: 1769645210)

FIGURE 2 Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Inverted Collar and Tie, 1994. Plastic reinforced with fiberglass and painted with gel-coat.

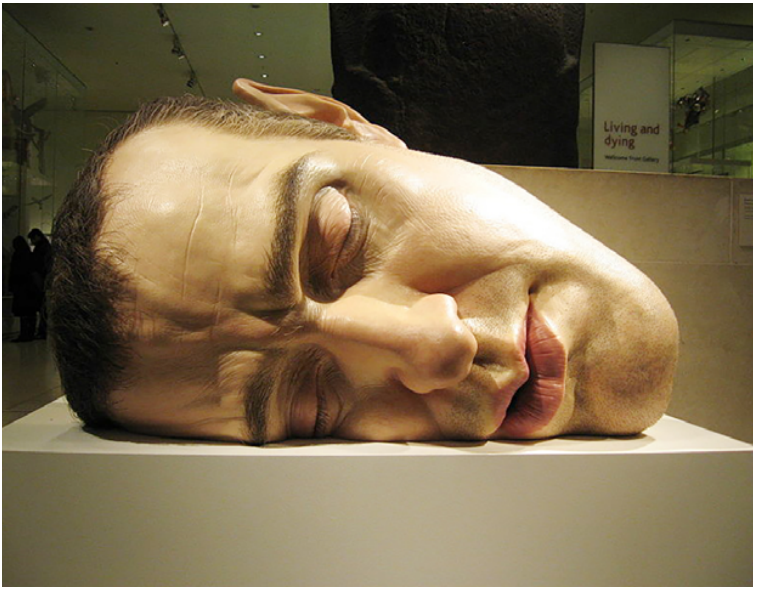

Example 3: “Artists such as Duane Hanson and Ron Mueck, pioneers of hyperrealism3, employed synthetic resins, fiberglass, techniques of casting, with molds made from plaster or silicone” (Figure 3) (García, 2009, p. 33).

(Photograph: Jack1956; courtesy: CC0, by Wikimedia Commons https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2d/Ron_Mueck_head.jpg).

FIGURE 3 Hyperrealistic self-portrait of Mueck asleep on a giant scale, 77 x 118 x 85 cm.

These examples reflect that artists became familiar with plastics, whose use has increased over time. Hence, as Shashoua states, “the proportion of plastics in museum collections has been growing, since museums keep acquiring objects that reflect daily life and historical events” (2008, p. 9).

The use of plastic in the Mexican artistic context

Artistic creations are a portrait of their historical context; such is the case of 20th century Mexican art which, due to globalization, was strongly influenced by the main European movements, although it managed to create its own language (Unidad de Apoyo para el Aprendizaje [UAPA], 2021).

The art of the period had aesthetic changes that were reflected in new expressive forms through the use of industrially-produced materials due to significant development in the fields of science and technology (UAPA, 2021). Of course, the international plastic boom also touched Latin American countries, such as Mexico, where its application was also extended to art, since its characteristics and properties allowed artists to represent the ideas and concepts they wished to transmit. Therefore, the Mexican context has art collections of modern and contemporary art made with plastic that must be conserved, which represents challenges and implications that require analysis and reflection to reach adequate decision making.

The Use of Plastic by Emilia Sandoval

Several previous experiences specifically led to artist Emilia Sandoval’s4 interest in working with plastics, as well combining them with other materials. Her first encounter was upon arrival in Adrián Paredes’s ceramics workshop in Oaxaca, where, inspired by the variety of markets and her surroundings, she began to experiment and combine materials. Her series Formas contenidas (2006) (Contained Forms 2006) was its product. Thus, she baked high-temperature clay on the sacks or plastic burlaps used in markets, using said materials and opposing elements and concepts to generate her discourse: clay vs. plastic and modernity vs. tradition (E. Sandoval, personal communication, April 2, 2015).

Emilia Sandoval comments that “The next piece remits me to the markets and the burlap or sacks used to place and show various products for sale” (personal communication, April 2, 2015); to simulate them, in this case the artist implemented small balls of white clay (Figure 4).

(Photograph: Emilia Sandoval, 2021; source: https://emiliasandoval.tumblr.com/formas%20contenidas)

FIGURE 4 Emilia Sandoval, Adherencia (from the series Formas contenidas), 2006. High temperature ceramic, hemp thread and burlap, 40 x 67 cm.

Furthermore, this led her to reflect on the use of plastic; she describes it as: “I felt the need to work from home and at my own times, which led to the idea of seeking a material that was part of my daily life…” (E. Sandoval, personal communication, April 2, 2015).

Observing an image that was part of the scenery on her way to Oaxaca airport (Figure 5), which presented a great combination of plastic bottles with a bougainvillea plant at the end of plot, materials opposed to each other, linked to the influence of the textile tradition in the Oaxaca detonated the idea of creating works made of plastic as though they were textiles, such as the series Paisajes (des)compuestos ((Dis)composed Landscapes) (E. Sandoval, personal communication, April 2, 2015) (Figure 6). The artist collected plastic bags from products she herself consumed, cut them into strips and separated them by shade so as to weave different landscapes on a weft of plastic bags, based on photos of different landscapes throughout Mexico she herself had taken.

(Photograph: Emilia Sandoval, 2021; source: https://emiliasandoval.tumblr.com/paisajesdescompuestos)

FIGURE 5 Emilia Sandoval, Naturaleza intervenida (from the series Paisajes (des)compuestos), 2007. Printed with ultrachrome ink, 71.12 x 101.6 cm.

(Photograph: Emilia Sandoval, 2021; source: https://emiliasandoval.tumblr.com/paisajesdescompuestos)

FIGURE 6 Emilia Sandoval, I (from the series Paisajes (des)compuestos), 2007. Woven, 33.5 x 43.5 cm.

According to Jiménez, in the 2010 series Espacio residual (Resid ual Space), Sandoval broaches the subject of appropriation, since she generated a visual reconstruction from a set of circles cut out from color proofs and photographs she took when studying for her BA. Each circle is embroidered on a transparent plastic, joined by a bead also made of plastic (Figure 7) (2015, p. 27).

(Photograph: Emilia Sandoval, 2021; source: https://emiliasandoval.tumblr.com/espacioresidual)

FIGURE 7 Emilia Sandoval, Lustro III (from the series Espacio residual), 2010. Sensitive film, beads, thread, transparent plastic and paint, diameter 90 cm.

Adoption of plastic bags as a material for expression

In 2009 Emilia Sandoval obtained a residency to study in Vermont, USA, where her sources of inspiration were nature and a patchwork shop, hence she began to experiment with different materials in that type of technique (Jiménez, 2015, p. 29).

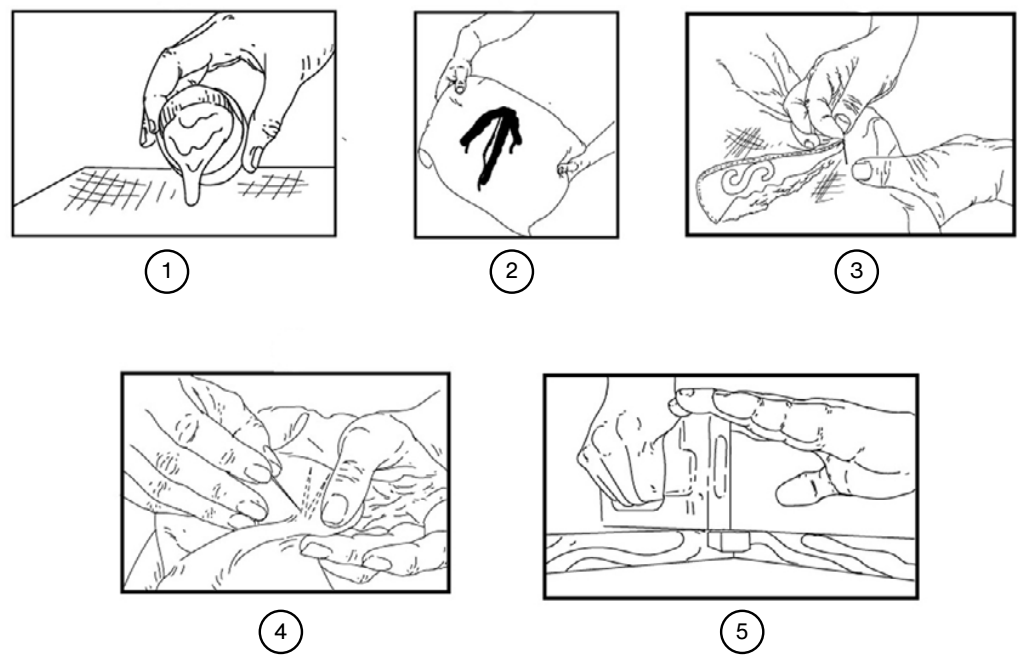

The use of plastic culminated in the creation of the series Botánica: nuevas especies (Botany: New Species), a set of pieces made between 2009 and 2011, which includes Tasajo Norstrom. Jiménez indicates they were made with plastic bags (which implies reusing an industrially produced material whose initial use is trade, since they serve as containers for commercial products by different brands), combined with other materials, such as pine wood in the canvas frame, linen cloth as a support and acrylic paint, plastic beads, and cotton thread as decorative elements. To do so the artist carried out a manual and artisanal procedure-a series of steps that comprise the work’s creative process- whose artistic technique is characterized by thoroughness and patience (Figure 8) (2015, p. 52).

(Scheme: Karla Jiménez, 2021; source: Jiménez, 2021)

FIGURE 8 Creative process for the pieces in the series Botánica: nuevas especies.

As Emilia Sandoval mentions (E. Sandoval, personal communication, April 2, 2015), the pieces acquire organic forms as part of a reinterpretation of various plants, whose title begins with the scientific name followed by the name of the shop or brand of the plastic bag used as an aesthetic and pictorical resource.

Conservation of works made of plastic

As Santabárbara established, “the problem of conserving contemporary art appeared suddenly with the premature aging of works made with the new materials introduced in the mid 20th century, particularly on works made with plastics and their derivatives” (2018, p. 257). This “due to the fact that plastics have a short useful life compared to traditional materials” (Shashoua, 2008, p. 9).

Furthermore, as Santabárbara proceeds: “it was noted that in relation to what had preceded it, this art went beyond the material, that is to say, it had passed from constructing or representing a message to having a strong intellectual and conceptual charge” (2018, p. 257). This is the premise on which the evolution of art conservation and restoration theory is based, since, as contemporary restoration theory indicates, it retakes and adapts classical theories that developed in different countries in the world, such as Germany, Italy and Holland: it does not substitute them, enabling the use of more flexible conceptual instruments (Muñoz, 2004, p. 14). This has, necessarily, had a direct repercussion on the criteria the discipline at hand should adopt, and which obey specific problems, as will be seen later.

Therefore, in 1999 the Dutch Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (Stichting Behoud Moderne Kunst [SBMK]) developed and published The Decision-Making Model for the Conservation and Restoration of Modern and Contemporary Art (Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art, SBMK, 1999, p. 4).

Since then, this model has served as a valuable tool to navigate through complex conservation problems in modern and contemporary art, as well as to discuss and document decision making processes and train young professionals. This methodology was subsequently revised and updated, in 2019, as a response to emerging forms of contemporary art and ensuing conservation challenges, along with the results of recent research [Cologne Institute of Conservation Sciences (CICS), 2021].

This model has been adopted in Mexico to solve different conservation problems encountered with works made of plastics. However, it is worth analyzing the way in which it has been approached and applied, to disseminate the reaches, challenges, implications and inherent limitations and, thus, facilitate decision making for the conservation of such works.

To do so, we will carry out a comparative analysis between several works, such as Tasajo Norstrom, by Emilia Sandoval, Famosos edificios históricos mexicanos (Famous Mexican Historical Buildings), by Dennis Oppenheim and Fluxus, by Melanie Smith, as well as easel paintings with a polypropylene film support and oil paint layer by the artist Jordi Teixidor, allowing us to conceive the pieces and installation in greater detail regarding similar authors and creations. It should be noted that due to the fact that the choice of case studies -including Tasajo Norstrom- was done prior to the 2019 review and updating of the model, this research used the first version.

The following set of queries were considered for this analysis, to invite the reader to delve into the problems within the field of contemporary conservation: where were the examples taken from and what were the reaches of its conservation problem? Where did the conservation problem originate and what were the results of the study?

The Tasajo Norstrom example was taken from a thesis whose main motivation was to study the deterioration of plastic and, therefore, solve the conservation problem; furthermore, to serve as a guide to study the deterioration of modern or contemporary works made of plastic. Another stated objective was to learn about plastic’s interaction with other materials that form part of said works (Jiménez, 2015, p. 2). The research met the first two aims, but not the third, due to the fact that while identifying the need to establish limits to the execution of empirical analysis, the experimental procedure was in constant flux.

The case study Famosos edificios históricos mexicanos was based on the diagnostic report and corresponding conservation proposal, while the example Fluxus comes from the piece’s restoration report. In both cases, the proposal and intervention focused on conserving the original object, maintaining the elements that fulfill their function, substituting those that do not, a decision based on the artists’ intentions and respect for the original technique (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 239).

The example of Jordi Teixidor’s works emanates from a research article whose main aim was to learn the artist’s intention regarding conservation. It also aimed to establish to what extent natural aging of polypropylene, combined with materials that constitute the paint layers, in this case of lipid type, would be a discrepancy with said intention (Llamas & Talamantes, 2012, p. 75). Both objectives were met.

It should be noted that both Tasajo Norstom and Jordi Teixidor’s work were born of the artists’ concern to ensure them the greatest perdurability. They clearly represent the interest of certain creators to conserve their work from the outset. On the subject, both investigations reflect the challenges implied by developing strategies to solve a problem when there is an initial discrepancy between the artist’s intention of conserving his work and the choice of plastic as a constituent material therein, for the latter’s degradation is in evitable and the time it takes to advance depends on the type of polymer.

Famosos edificios históricos mexicanos and Fluxus came about through the interest and institutional need on the part of Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo (MUAC) of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (unam) to conserve the pieces that are part of their collection.

Comparative analysis of the case studies

Tasajo Norstrom is a square-shaped collage that is part of the Botánica: nuevas especies series and was made with the same materials as the rest of the set. Its name is related to the image displayed and provides information on its production (Figures 9, 10 and 11) (Jiménez, 2021, p. 46-47).

(Photograph: Emilia Sandoval, 2020; source: https://emiliasandoval.tumblr.com/botanica).

FIGURE 9 Emilia Sandoval, Tasajo Norstrom (from the series Botánica: nuevas especies), 2014. Acrylic paint, fragments of plastic bag, synthetic filling, thread and beads over linen on a wooden frame. 50 x 50 x 3 cm.

The piece’s significance resides in the reflection on cons umerism and its impact on nature. Hence, the artist uses bags as an aesthetic and pictorical resource because she can reproduce the image’s form and color with them: therefore, they play a fundamental role in transmitting its meaning since, being reused, the critique of consumerism makes sense (Jiménez, 2021, p. 57-58).

To provide a solution to the conservation problem for this piece it was necessary to propose an experimental phase, which con sisted of performing analytical tests to know both the composition of the plastic bags that form part of the artist’s stock (since the hypothesis was that they were polyethylene) as well as their behavior, identifying the deterioration they might demonstrate down the line: being a recent work, those it presented were not of a considerable enough degree that would permit an evaluation of its state of conservation (Jiménez, 2021, p. 72).

The identification test results corroborated that the plastic bags used to create the Botánica: nuevas especies series, including Tasajo Norstrom, are polyethylene, while the degradation tests were checked against bibliography on the degradation of polyethylene products, to establish the causes and mechanisms which produce them as part of the bags’ dynamics of alteration (Jiménez, 2021, p. 113).

Discrepancies were identified between the material and its meaning as a result of deterioration. It was determined that they are affected by deteriorations that modify their aesthetic appearance, such as color, and less so by those that would endanger the pieces’s stability, as the artist believed when she expressed her concern over conserving them (Jiménez, 2021, p. 119). Hence, a guide to determine the state of conservation of the polyethylene bags was established (Jiménez, 2021, p. 118).

Consequently, conservation proposals were submitted-thus providing a solution to this problem-for polyethylene bags according to their material conditions. It is worth noting that selecting the most viable option should mainly take into consideration the state the bags are in, as well as other variables that influence the de cision making, such as time, context, function, the meaning of the work and the artist’s opinion (Jiménez, 2021, p. 120).

The work Famosos edificios históricos mexicanos (I, II, III and s/n [without number]) was created by the American artist Dennis Oppen heim5 by assembling everyday plastic utensils that themselves form four structures or sets, accompanied by an electrical installation under each base to illuminate the piece. These assemblies represent Mexican architectural structures (Figure 12) (Jiménez, 2015, p. 3).

(Photograph: Karla Jiménez, 2015, source: MUAC).

FIGURE 12 Dennis Oppenheim, Famosos edificios históricos mexicanos (I, II, III y s/n [without a number]), 1998. Assembly of everyday plastic utensils and electrical installation with lamps, measurements variable.

Their significance is linked to the word “spree”, the name of an exhibition held in 1998 in Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil (MACG), in which said artist was invited to participate. Hence, during a first trip he visited markets in the then Federal District (now Mexico City) where he acquired various elements to make his work, in this way he connected with the spirit of Mexican culture; during a second visit he playfully created each of the structures that comprise the set. Therefore, the plastic utensils are a fundamental part of transmitting the work’s concept (Jiménez, 2015, p. 27-29).

Experimental analyses were performed, both simple and chemical, to identify the composition of the plastic elements. In this regard, there was a hypothesis that they were made of polyethylene -as previously mentioned-polypropylene or PVC since these plastics are commonly used to produce this type of products. Only in one class of utensils was it possible to prove that they were made of polyethylene (Jiménez, 2015, p. 20-21).

Unlike Tasajo Norstrom, the diagnosis of Famosos edificios históricos mexicanos was done by comparing its original state and its current one, hence in this case there was no need to analyze the material to learn how it behaves. From this, it was identified that the work presented most of its elements in their original conditions.

The discrepancies between meaning and the material identified were due to missing elements and deterioration that threatens both the aesthetic aspect and the structural stability of the work, as they modify its meaning, by threatening the idea and, since the elements do not transmit anything individually, the aspect of the set (Jiménez, 2015, p. 39-40). Based on this, several alternatives to ensure its conservation were presented, which were subsequently evaluated according to the values (aesthetic, artistic, technological, and functional) that contribute to maintaining the work’s original concept. The best option was the substitution of deteriorated elements, which should try to be done with utensils of the same brands and colors, if it is impossible to purchase them because they are no longer produced, they must be the same shape as the originals (Jiménez, 2015, p. 48-52).

It is noteworthy that this proposal differs from the one made to establish conservation options for the piece Tasajo Norstrom, where the possibility to choose this option in accordance with its material state was left open, which does not occur in this case.

Fluxus is an installation composed of 248 pieces of plastic, ru bber and metal made by the artist Melanie Smith,6 each is an industrial creation shaped like bottles with conical tops: it is made of common sugar shakers worked by the artist to look like baby bottles (Mata, 2014, p. 239). “In it is portrayed fragmented feminine corporeality, whose title refers to another of the artist’s concerns, the flows of communication between the body’s inside and outside” (Figure 13) (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 7).

(Photograph: Mariana Almaraz Reyes, María Eugenia Desirée Buentello García, Ana Lanzagorta Cumming y Paula Rosales-Alanís, 2012; courtesy: ENCRYM-INAH).

FIGURE 13 Melanie Smith. Fluxus, 2007. Installation of plastic, rubber and metal parts, variable measures.

In order to understand the work’s current conditions it was necessary to create a line of life based on the documentation and research of the different factors that composed and influenced it. Thence information was obtained that the piece turned out to be a replica (current piece), made by the artist in 2007 to exhibit it in La era de la discrepancia (The age of discrepancies, 1968-1997) since the original 1991 piece, exhibited in Belgium, had never returned to Mexico. It should be noted that the replica was composed of 248 elements, of which only 135 elements were exposed (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 17).

Furthermore, the conditions of both the original work as well as the current one had to be considered for the diagnosis. It noted that the plastic containers the artist used for the recent version have an acrylic enamel, applied to resemble the color of the original piece, due to the fact that Smith did not find the same containers on the market (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 27). This clearly reflects that the aesthetic appearance of the piece is important to maintain its meaning. It is worth mentioning that the 113 elements that were found in a warehouse presented differences both in the color of the nipples and the lack of rings as well as in the stability of the covering (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 18-22).

Therefore, the separation of elements and deterioration represents a fundamental part of the problem to conserve the piece. The discrepancy resides in deterioration that affects the aesthetic and functional values, for they directly affect the image, its conformation and, therefore, its meaning (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 23-24).

Different conservation options should be evaluated, weighing the advantages and disadvantages of each, to select the one which will best fit and respect the piece's principal values. In that regard “it was decided that restoration would be the best alternative, as it respects the original materials that fulfill their function, without threatening the concept” (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 7).

Unlike Tasajo Norstrom and the first example, this intervention did take place. It focused on conserving the original concept, maintaining the elements that fulfill their function and replacing those that did not. The decision was based on respecting the original technique and the creator’s intention.

The works by Jordi Teixidor are, as mentioned, easel paintings on a support of polypropylene film with an oil paint layer. They belong to abstractionism, hence their materiality is related to the experimentation that characterized said movement as well as the personal search for technical possibilities to enrich the aesthetic part of his pieces (Llamas & Talamantes, 2012, p. 75).

The following similarities were noted between this example and Tasajo Norstrom, foreseeing various factors to its conservation solution: it came up as a concern on the artist’s part. It was impossible to determine the current condition of his works in relation to their deterioration since, being recent, his materials will not have suffered transformations. Therefore, the conservation challenge centered on studying the behavior of polypropylene, to establish to what extent its deterioration can affect the work’s meaning (Llamas & Talamantes, 2012, p. 75-76).

Another common point in between Tasajo Norstrom and the present example is the proposal and execution of an experimental procedure to identify the plastic used to make it. Both cases involved infrared spectroscopy analysis by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), to indicate the polymeric nature of the support, and experimental tests-for example, aging (exposure to uv radiation and changes of temperature and relative humidity)-to learn about the plastic’s behavior. Furthermore, in the case the FTIR was also applied to determine the painting technique and to demonstrate the chemical changes the materials experienced as a consequence of being submitted to aging (Llamas & Talamantes, 2012, p. 80).

The above led to the conclusion that the deteriorations in the polypropylene support inevitably affect the paint layer, due to the progressive and unstoppable degradation of the support that will end up affecting the adherence between the pictorical layer and what sustains them. Hence, it was determined there is a discrepancy between the intention to conserve the piece and the choice of sustaining material (Llamas & Talamantes, 2012, p. 83), from which the study did not foresee establishing options of conservation, as occurred in the case of Tasajo Norstrom.

Conclusions

The challenges involved in the process of reflection required to propose various options of conservation and solutions for the problems of the case studies included herein concern the very nature of the plastics used to create the works:

They are very different materials to those used in art in the past, since they are constantly updating, due to technological advances and industrial production, in addition to being intrinsically unstable due to the fact that their aging process has not yet finished, that is to say, there is a physicochemical continuity of the products [Righi, 2006, p. 15].

This situation questions the idea of the artistic object and, therefore, its conservation; nevertheless, it should be understood that it is precisely the idea or concept one strives to maintain over time. With this premise, the question is not whether it is relevant to conserve this type of pieces but, rather, how they should be conserved, and whether this should be done through the preservation of the material-if that is the basis of its concept or meaning.

The answer is based on the proposal and execution of various conservation options: direct ones, which do not necessarily consist of carrying out restoration processes, but rather the substitution of elements or material that form the object, and indirect ones, with registering and documentation and/or preventive conservation.

It is worthwhile to state that the comparative analysis of the case studies reflects the importance of documentation to lead to adequate decision making. There are limitations in this regard, according to the specific conservation problems, which is an integral part of the theoretical-practical process that the solution implies.

Considering the above, the figure of the restorer-conserver is not only limited to intervening on the object or context, he/she also works as an advisor to contemporary artists, by contributing through his/her knowledge to solving conservation problems identified through concerns on the part of the artists.

To conclude, following the methodology analyzed in the present text demands that the restorer-conserver does not take it at face value, but rather, researches the model mentioned herein and, if necessary, revises the process of reflection by complementing the information on various factors that should be considered: condition, meaning, discrepancies between the methodology and the reflection, as well as conservation options. Therefore, it is important and necessary to have continuous dissemination and feedback on the process of research and reflection implied by the application of this methodology, which has been used over time by colleagues in the field of conserving contemporary artworks.

REFERENCES

Almaráz, M., Buentello, D., Lanzagorta, A. y Rosales-Alanís, P. (2012). Fluxus, Melanie Smith. Informe de restauración [material inédito]. México. Seminario Taller de Restauración de Obra Moderna y Contemporánea, Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía-Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. https://mediateca.inah.gob.mx/repositorio/islandora/object/informe%3A580 [ Links ]

Chiantore, O. (1999). Los materiales plásticos en el arte contemporáneo, su transformación y decadencia. En Arte Contemporanea Conservazione e Restauro. Nardini Editore Fiesole. Traducción por María Consuelo Chufani Z. Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Musegrafía, septiembre 1999. [ Links ]

Cologne Institute of Conservation Sciences. (2021 [2019]). The Decision-Making Model for Contemporary Art: Conservation and Preservation. Cologne Institute of Conservation Sciences/Technology Arts Sciences TH Köln. https://www.th-koeln.de/mam/downloads/deutsch/hochschule/fakultaeten/kulturwissenschaften/f02_cics_gsm_fp__dmmcacp_190613-1.pdf [ Links ]

Foundation for the Conservation of Contemporary Art (SBMK). (1999). The Decision-Making Model for the Conservation and Restoration of Modern and Contemporary Art. SBMK. 1997/99/Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage. https://sbmk.nl/source/documents/decision-making-model.pdf [ Links ]

García, S. (2009). Los polímeros en la época de difusión de estilos artísticos. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad (21), 27-36. https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ARIS/article/download/ARIS0909110027A/5756 [ Links ]

Ifema Madrid. (12 de agosto de 2021). Pop art: qué es, artistas y características [página web]. https://www.ifema.es/noticias/arte/pop-art-que-es-artistas-caracteristicas [ Links ]

Jiménez, K. (2015). Informe del diagnóstico y propuesta de conservación de la obra Famosos edificios históricos mexicanos del artista Dennis Oppenheim perteneciente al Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (Informe de licenciatura). Seminario Taller de Restauración de Obra Moderna y Contemporánea, Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía/Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [ Links ]

Jiménez, K. (2021). El estudio del deterioro del plástico en las obras que conforman la serie Botánica: nuevas especies de la artista Emilia Sandoval, a partir del prototipo conocido como Tasajo Norstrom (Tesis de licenciatura). Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía-Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [ Links ]

Llamas, R. y Talamantes, C. (febrero, 2012). Capas pictóricas sobre plástico en el arte contemporáneo: estudio analítico del polipropileno sometido a ciclos de envejecimiento. En Conservación de Arte Contemporáneo [Recurso electrónico]: 13.ª Jornada, [organiza] Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Departamento de Conservación-Restauración (pp. 75-86). https://issuu.com/museoreinasofia/docs/publicacion-13-jornada/5?e=6820926/1649677 [ Links ]

Mata, A. (2014). La mutación del objeto cotidiano a la obra de arte. La conservación de la obra Fluxus de Melanie Smith. En Conservación de Arte Contemporáneo [Recurso electrónico]: 15.ª Jornada, [organiza] Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Departamento de Conservación-Restauración (pp. 239-248). https://issuu.com/museoreinasofia/docs/1-286 [ Links ]

Muñoz, S. (2004). Teoría contemporánea de la restauración. Síntesis. [ Links ]

Righi, L. (2006). Conservar el arte contemporáneo. Nerea. [ Links ]

Santabárbara, C. (2018). La teoría de la restauración de arte contemporáneo: criterios de intervención. En Conservación de Arte Contemporáneo [Recurso electrónico]: 19.ª Jornada, [organiza] Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Departamento de Conservación-Restauración (pp. 257-266). https://www.museoreinasofia.es/sites/default/files/publicaciones/conservacion_de_arte_contemporaneo_compressed_0.pdf [ Links ]

Shashoua, Y (2008). Conservation of Plastics: Materials Science, Degradation and Preservation. Elsevier. [ Links ]

Unidad de Apoyo para el Aprendizaje. (12 de agosto de 2021). Arte mexicano del siglo XX. https://programas.cuaed.unam.mx/repositorio/moodle/pluginfile.php/164/mod_resource/content/1/arte-mexicano-s-xx/index.html [ Links ]

1Editorial translation. All quotes where the original text is in Spanish are also ed itorial translations.

2A movement with realism tendencies that originated in England during the 50s and which took off in the USA in the 60s, in which the elements are consumer objects mass-used by society (IFEMA, 2021).

3A movement born in the USA in the 60s where artists depict modern society just as it is, in its daily reality. Those conceptions are materialized in pieces that resist the passage of time and surpass traditional realism, to the extent that it had always limited itself to reproducing the reality the artist saw, highlighting partial aspects with a subjective criterion and conditioned by the limitations of human perception (García, 2009, p. 32).

4Emilia Sandoval is an artist from Chihuahua who lives in the state of Oaxaca. From the outset of her career, she was interested in the manual process of mixing differ ent materials and observing their behavior. Thus her production is characterized by experimentation through various art techniques, such as photography, installations, sculpture and intervention, among others, and whose experiences led her to employ plastics as part of the composition of her works (Jiménez, 2015, p. 24).

5“Dennis Oppenheim belongs to the pioneering generation of conceptual art in the USA, a current tin reaction against minimal art, for it introduced the concept of dematerialization, focus on the idea and avoiding the form. During the 90s the mexican cultural context and artistic environment were characterized by welcoming foreign artists who used Mexico City as an experimental laboratory, including Francis Alÿs, Melanie Smith, Thomas Glassford, etc…” (Jiménez, 2015, p. 31).

6At the start of her career, Smith had an important influence from the minimalist current, in which Richard Serra and Frank Stella stand out. She came to Mexico in January 1989 along with other British artists who contributed to the consolidation of the performance and the installation as types of contemporary Mexican art (Almaráz et al., 2012, p. 14 -15).

Received: July 22, 2021; Accepted: August 18, 2022; Published: December 28, 2022

texto em

texto em