Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Intervención (México DF)

versão impressa ISSN 2007-249X

Intervención (Méx. DF) vol.12 no.24 México Jul./Dez. 2021 Epub 26-Set-2022

https://doi.org/10.30763/intervencion.257.v2n24.36.2021

Articles

Revelations of the Divine Proportion in La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, a 17 th Century Painting Attributed to Baltasar de Echave Orio

*Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente (ECRO), México. caminoford92@gmail.com

X-ray technology provided relevant support in the compositional analysis of the painting, La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, attributed to Baltasar de Echave Orio. The unprecedented and amazing results revealed the creative mastery that crafted this work of art and proved that the artistic beauty of the piece (immersed in a problem of attribution) was conditioned by the golden section and its creator’s meticulous compositional analysis. From the conservation-restoration perspective this study opens a novel view that recognizes the technical audacity of a cultured, European-trained artist who had access to prints from the Old World that were disseminated across 17th Century in New Spain.

Key words: golden section; compositional analysis; radiological analysis; manufacturing technique; il disegno

En el análisis compositivo de la pintura La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, atribuida a Baltasar de Echave Orio, fue relevante el apoyo tecnológico de los rayos X. Los sorprendentes resultados, inéditos, revelaron la maestría del proceso creativo que conllevó la manufactura de esa obra de arte. Se demuestra que su belleza artística estuvo condicionada por la sección áurea y el meticuloso análisis compositivo de su creador; implicado en un problema de atribución, con este estudio se abre un nuevo panorama desde la conservación-restauración, que reconoce la audacia técnica de un artista culto, con formación europea y con acceso a los impresos del Viejo Continente difundidos en la Nueva España del siglo XVII.

Palabras clave: sección áurea; análisis compositivo; análisis radiográfico; técnica de manufactura; il disegno

Introduction

This article is a partial compendium derived from the evaluation of the analytical technique used for the thesis in process titled Análisis de la técnica y los materiales presentes en la manufactura de la pintura “La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís”, atribuida al pintor vasco Baltasar de Echave Orio, supported by restorer David A. Flores Rosas from the Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente (ECRO, Mexico), under the guidance of researcher Yolanda P. Madrid Alanís, chemist Javier Vázquez Negrete, and Consuelo Chufani as advisor. All are part of the Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (ENCRyM-INAH, Mexico). The team has been involved in this on-going investigation for five years now.

The subject is a painting on wood support medium (277 x 207 cm) made in the first half of the 17th century. Since 1893, it has been attributed to the Basque artist Baltasar de Echave Orio (Revilla, 1893, p. 75). At first, the painting belonged to a Franciscan convent, and in 1855 it was included in the collections (Báez, 2009, p. 229, 281-282) gathered by don José Bernardo Couto for the gallery of the Antigua Academia de San Carlos, in Mexico City (Couto, 2006, p. 54). As chance would have it, the painting later became part of the collections of the Museo Regional de Guadalajara (MRG, Mexico) (Cruz-Lara, 2018-2019, pp. 8-14) where it was considered one of the jewels of this important cultural venue (Zuno, & Razo, 1957, p. 1). It is currently an asset of Mexico, recognized by INAH for its artistic and historic value.

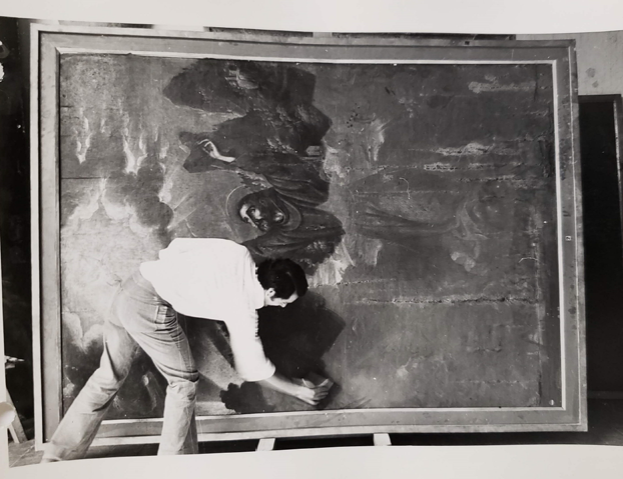

It should be noted that the painting at the art gallery of the Museo de Bellas Artes de Jalisco (founded in 1918 and currently known as the MRG) had not been studied with the methodology proposed in this ACADEMIC REPORT due to social circumstances in the country, which influenced the cultural policies of the Museum, more focused at that time on actions to safeguard its permanence as a cultural institution (Cruz-Lara, 2017, pp. 18-31). One of these actions, however, was of interest to us because it had a direct impact on the materiality of the painting. That action was a restructuring effort promoted in 1975 by then director, José Guadalupe Zuno, financed with federal resources granted by former President Luis Echeverría Álvarez (Sánchez, 2015, p. 29-32). This event brought about an intervention on the painting by specialists from the Cultural Heritage Restoration Department at INAH (Oropeza, 1975), currently the Coordinación Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural (CNCPC, Mexico). In an interview, restorer Manuel Serrano †, who headed the restoration of this painting between 1975 and 1976 (Figure 1), mentioned that because of Mr. Zuno’s pressure to speed the restoration project and due to lack of scientific equipment (M. Serrano, personal communication, July 6th, 2018), restorers were unable to perform further tests to characterize the materials of the painting. They were, however, interested in conducting studies before restoring La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís and were thus able to produce an accurate iconographic description. They also had IR and UV photographs done by photographer Irmgard Groth, which at the time constituted a very significant technological advancement (Serrano et al., 1976). Such results reflected the professional training received by the first Mexican restorers from George Messens and Sheldon & Caroline Keck, when in 1965 they participated in founding the Centro Regional Latinoamericano de Estudios para la Conservación y Restauración del Patrimonio Cultural (Cerlacor, currently CNCPC) mainly promoted by Coremans and Castillo Negrete in Mexico City (Giorguli, 2014, pp. 74-87; López, 2014, pp. 100-119). From a theoretical and practical interpretation, this ACADEMIC REPORT contributes to studies that have focused on investigating the Estigmatización as a source of knowledge for conservation/restoration, and similar fields.

(Photograph: Manuel Serrano, October 1975 [negative CXXVIII-A/14-2-3]; courtesy: Collection of the Historical Archive of the Restoration Department, Museo Regional de Guadalajara, INAH, México)

Figure 1 Unpublished photograph of a restorer (probably Rolando Araujo) in the intervention of La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, in the MRG workshop, in 1975.

The echave workshop and the problematic regarding the authorship of the painting

The Estigmatización has been attributed to Baltasar de Echave Orio (c. 1558, Aizarnazabal, Euskadi-1623, Mexico City, New Spain) an artist of the Basque diaspora who settled in New Spain, where he partnered with gilder Francisco Ibía Zumaya (1532, Zumaya, Euskadi-?, Mexico City, New Spain) (Corvera, 2018, pp. 36-37), who was also Basque and the father of Isabel Ibía “la Zumayana”, who married Echave Orio in the year 1582 (Toussaint, 1965, p. 65; Flores, 2017). This very special union resulted in a dynastic workshop that lasted three generations (Ruiz, 2004, pp. 183-207): Manuel de Echave Ibía (1587-c. 1640) (FamilySearch, 2021), Baltasar de Echave de León (?-1644), possible son of Manuel de Echave Ibía, and Baltasar de Echave Rioja (1632-1682), son of Echave de León (Toussaint, 1965, p. 96; Ruíz 2004, pp. 183-207). It is worthwhile noting that because the descendants of the painter shared the same name, they all used a similar signature (Carrillo, 1953, p. 50-55), which has made it difficult to study their personalities and artwork, all adhering to the same pictorial traditions yet each with particular technical qualities (Arroyo et al., 2012, pp. 85-117).

The problem with this unsigned painting was that the technique used to execute it was unknown, and such information is crucial to define the best conditions to preserve it and restore it in the future, according to the example of Yanhuitlán, Oaxaca (Madrid & Castañeda, 2009-2010). To this investigation we added the alleged attribution to artist Baltasar de Echave Orio, challenged by Guillermo Tovar de Teresa (1979, p. 464; 1982, p. 155; 1992, p. 118), and José Guadalupe Victoria (1994, p. 95 y 143).

Our investigation set out to learn about the creative process behind La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, and to determine whether its technological execution adhered or not to the materials and practices described in European treatises.

Conservation and restoration have turned things around for this kind of study because those contribute to results about the materials that can be used by other disciplines. Noteworthy among these is art history, the research tools of which are used by conservators to obtain information that spans across several disciplines, as demonstrated by recent research on the work of Baltasar de Echave Orio -recognized for his inventions and reasoned compositional rhetoric (Cuadriello et al., 2018, pp. 13-27). Although its objectives are different from the ones set out in this report, the results of recent studies on Echave Orio are extremely relevant to analyze better his painting and the practices at his workshop (Pérez et al., 2021, pp. 1-42). Also are crucial the investigations that look into the plastic details of the enigmatic and varied artistic legacy of Echave Orio, which are sometimes linked to the Flemish tradition and others, to Italian and Spanish currents (Belgodere, 1969-1971, pp. 18-24).

According to Meza (2014, pp. 134-136), when conservators/restorers work on a painting, they need to study its composition lines, which is one of the tools of art historians -already mentioned here- that is useful to assess the composition lines of an image such as this one, made to cause impact (devotion) in the visual perception of the spectator (believer). In other words, the study of compositional geometry leads to a better understanding of a painting, as expressed by Victoria (1994, pp. 102-204) in his monograph on the life and work of Echave Orio.

Compositional geometry analysis has been taken up in other studies of Novo-Hispanic art; for example, in a piece by Antonio Arellano (active in the first third of the 18th century) where composition lines that support the visuality of the image were found. The painting was analyzed with infrared light that revealed outlines and a correction (Castañeda, 2017, p. 146, 167), which suggest a freer drawing relative to the results of the infrared photography of La estigmatización (photographs reserved for the research thesis that originated this ACADEMIC REPORT), in which we observed that the final painting was conditioned by a careful preparatory drawing that led to postulate the absence of pentimenti in the painting.

This proposal for an interdisciplinary methodology includes a log of infrared photographs and emphasizes the study of the compositional geometry of the painting. This required a digital radiological analysis directed at discovering that part of the technology and its materiality (Bautista, 2020). Following this practice and simple methodology revealed the artist’s artifice to transfer his preparatory drawing to the final wood panel for La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís. It should be noted that this technical aspect of the disegno had not been discussed in such depth before in a research project of this kind on Novo-Hispanic art, so this report attempts to make a methodological contribution applicable to other easel paintings. The potential results of this study around the manufacturing technique of the Estigmatización painting are:

1) Different order of resolutions to the problematic: social, economic, and technological, of interest for anthropology, sociology, economics, history, plastic arts, and history of art.

2) A more detailed understanding of the modus operandi of the Echave workshop, which is a matter of interest for art history and plastic arts.

3) Promote the proposed methodological process to diagnose Novo-Hispanic paintings, which is a matter of interest for sciences applied to conservation/restoration.

X-ray technology has been employed as a non-invasive analytical technique to diagnose cultural assets (Palomino, 2020, p. 79), because it makes it possible to determine conservation status and even issue an opinion (Ineba, 2006, pp. 1-21). The qualities of this imaging technique have been widely accepted in the study of Novo-Hispanic paintings (Mederos et al., 2012, p. 21; Cano, 2020, pp. 124-133). In this case, our examination specifically deals with radiology and how it helped to reveal the structure of the artistic composition (Figure 2), which would not have been understood without intensive archive research, a review of ancient art treatises, and current documentation about restoring paintings on wood, all of which are fundamental to facilitate decision-making, a process that needs to precede any intervention. Thus, we had a foundation to build a methodology intended to respect material complexity (closely linked to the historicity of the object), which in this case is a product of predominating esthetics in the first half of the 17th century (Brandi, 1977, pp. 21-29).

(Photo: David Alberto Flores Rosas, November 12, 2019, Mexico)

Figure 2 X-ray execution processes, performed by Phd. Josefina Bautista, Lic. José Álvaro Zárate and Lic. Gerardo Hernández.

Although studies of materials in works of art analytically complement various techniques, this report highlights the role of radiology in compositional analysis to study materiality in Echave’s work, and how it has been a very important instrument to distinguish and identify Echave Orio’s own creative process and, therefore, of the painters that trained in his studio. Consequently, among other resources to analyze manufacturing techniques, our proposal here is that divine proportion is a relevant feature to corroborate works attributed to a member of this famous studio, and at the same time, to help deliver from anonymity those artists absorbed by master Echave Orio’s strong personality.

During the 16th century, the use of geometry and divina proporzione accredited painting as a scientific and intellectual activity, and not as a simple mechanical trade (Wade, 2017, pp. 61-73). Vasari, for his part, championed the nobility and dignity of art, under the premise that, “drawing is the origin of all arts” (Acidini, 2017, pp. 177-188). In Spain, painter and treatise writer Vicente Carducho used this proposal to exempt painters from paying sales tax (alcabala) to the Real Consejo de Hacienda (Carducho, 1633, pp. 167-177). These facts support the notion that Baltasar de Echave Orio, a member of the guild of painters in New Spain, considered it relevant to apply these axioms in his workshop.

The finding of underlying drawings in the creative process of a painting, authored by Spanish artists of the 16th and 17th centuries, has been revealing (Garrido, & Alba, 2006, pp. 20-40). Today, discovering traces of preparatory drawing transfers, or of hidden drawings under layers of paint marked a shift in the thinking of art historians. Before, they not only considered these colonial artists incapable of innovation, but also treated their artwork as mere copies of European engravings (Esponda, & Hernández, 2014, pp. 8-23).

In the case of La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, and in other works signed by Echave (Manrique, 1982, pp. 55-60), the image has been associated with a Flemish engraving by Maerteen de Vos (Figure 3). This engraving is visually attractive due to its descriptive language and the need to geographically place the scene in a landscape. The purpose of this was to give the image a sense of realism based on the specificity of the details and perspective. The system captivated the northern European artists of the 17th century to such a degree that they determined the use of the vanishing point, analyzed with a camera obscura. This knowledge evidenced the interaction between art and experimental science (Alpers, 1983, pp. 136-276; Wadum, 1995, pp. 148-154).

(Source: Rijksmuseum [http://hdl.handle.net/10934/RM0001.COLLECT.332115], public domain)

Figure 3 Maerten de Vos invenit, Hieronymus Wierix fecit. (1584). Franciscus van Assisi ontvangt de stigmata van Christus.

This painting also signals to a narrative in a hagiographic text: The Little Flowers of Saint Francis (Garzón, 2017), an aspect distinguishable in Italian art that also focused on assigning importance to the representation of the human body (Alpers, 1983, p. 78). Outstanding in this case is an engraving by Camilo Procaccini (Figure 4). Thus, the author of this anonymous painting demonstrated his concerned intention to describe for us, on one hand, a narrative of the sacred text in the manner of Italian artists, and on the other, his own visual culture by portraying a beautiful, detailed landscape in the manner of the Flemish painters. In this way, he created a unique plastic vocabulary that conjugated the intellectuality of treatises on Italian painting with the artistic ingenuity of the engravers and painters of Flanders. Complementing these ideas, the artist produced this very clear and unmistakable painting to understand both the mystical sense of the stigmata and the iconography in the depiction of a Seraphic Christ sharing his love and pain with the “little poor man of Assisi”, the Alter Christus who in this theophany reveals to us the sense of humanity signified by the love of God and of one’s fellowman (Villalobos, 2016, pp. 139-193). Simply put, the Saint from Assisi is cast as the ideal Christian who deserves to be emulated for his positive qualities, which is the main objective in the art of the Counter-Reformation.

(Artist: After Camillo Procaccini [Italian, Bologna 1555-1629 Milan]; publisher: Justus Sadeler [Netherlandish, Antwerp ca. 1572/1583-ca. 1620 Leiden]; medium: engraving; dimensions: 19 9/16 x 13/8 inches; source: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/728018)

Figure 4 Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata (1590-1620). The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund 1959 [59.570.161].

Using the current study methodology - put into practice for the first time with La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís attributed to Baltasar de Echave Orio - we looked at the meticulous compositional analysis (Gatica, 2006) of the painting and the method used to transfer the artist’s finely calculated drawing. Such “technical secrets” were revealed following the steps described below.

Three steps to the revelation of the golden number

1) Analysis of the drawing: We analyzed the qualities of the preliminary sketch the artist made of the drawing (Tardito, 1993, pp. 98-107). The technical process was described in detail in Pacheco’s El arte de la pintura (Pacheco, 2001/1646, pp. 482-483).

Procedure: A 1:100 scale pencil drawing was made using a square grid over a blank sheet of paper. The grid was based on another made over a photograph of the painting following the notion of preparatory drawings made by artists for transfer. In this procedure we obtained a result similar to the one resulting from a drawing made by Guercino (Figure 5). According to Pascual & Rodríguez (2015, p. 31), this practice drawing would be a first study of the image applying the ideas and design intended for the painting. The intention of both artists, who were contemporaries, is relevant as they represent the Saint with both arms completely outstretched to heaven, perhaps to express greater emotion and elicit the empathy of viewers in New Spain, and in this manner, convey to viewers a dichotomy of feelings: the love and pain represented by the stigmata of the Passion of Christ, who gave his life for humanity, a sensation suffered by Saint Francis of Assisi in his own flesh (Villalobos, 2016, pp. 139-193). Although there is no record of such drawings for the Echave studio, it is likely that the author of La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís made one similar to Guercino’s.

(Source: Klassik Stiftung Weimar, Museen, Inv.-Nr.: KK 8627, all rights reserved)

Figure 5 Giovanni Francesco Barbieri "Il Guercino" (1591-1666). (c. 1640-50). Der hl. Franziskus. Pen & ink in brown, brush in gray. Note the studied ecstatic expression on the face of Saint Francis of Assisi, and the grace with which Guercino made the saint with raised arms, to emphasize the religious sentiment of the implantation of stigmata, as we see it in the New Hispanic specimen.

Also noted is a division into thirds, defined by light and shadows, in accordance to the rule of thirds set forth in Leonardo da Vinci’s Linear Perspective (da Vinci, 2013, pp. 244-245), and this would be a potential example of the presentation drawing (Figure 6), an agreement between the artist and the commissioner of the painting (Pascual & Rodríguez, 2015, p. 31). Following the theoretical concepts of Macías (2017, pp. 17-30) and to complement the iconographic development of the painting done by other researchers (Toussaint, 1934; Ispizua, 1915, pp. 335-337; Serrano et al., 1976), we did an ekphrastic exercise which helped us understand the three divisions of the image.

(Illustration: David Alberto Flores Rosas, 2019; pencil on paper, 21.6 x 27.9 cm, scale 1:100; ECRO, México)

Figure 6 Analysis of the preparatory drawing for the painting La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, MRG.

In the first third, one observes a very luminous blue sky where the clouds open resoundingly to the Seraphic Christ who imposes stigmata upon the hands, feet, and heart of Saint Francis. His expression is one of great mystical anointment. The Saint from Assisi is in the second third. Here the stigma upon his heart is a punctum in the visual comprehension of the image to such a degree that the painter, notable for his perfect colors, preferred an uncomplicated technique to portray a tear in the coarse wool so we could see the chest wound. This is a distinct element of Franciscan ascetism that identifies the holy founder of the Order of Friars Minor. In the gloomiest part of the painting, the lower left-hand corner, hidden behind a peculiar trunk is friar León, “the Lord’s Little Lamb”, contemplating the ecstasy of the saint. Third third bears the largest number of prior interventions.

It should be underscored that the artist, who must have been very influential in colonial times, had a masterful way of painting the complex narrative of the hagiographic passage of the Seraphic Saint, portrayed in a landscape of exuberant vegetation. Tall, robust trees, like oaks stand out. A pristine river carrying the sound of waterfalls is crossed by a bridge that takes us on the right side to a road that opens to a place of worship in front of a hermitage. Behind this there are huge mountaintops, but despite their great height and the risk involved, there is a house on the top of one of them. If one follows the river, further on an etxea (meaning hamlet in Euskara or Basque) appears as if lost among the hills. According to Toussaint (1965, p. 94) all of these elements indicate that the artist “wanted to see a landscape” very close to Baltasar de Echave de León’s artificious and sensitive blue sceneries (Vargaslugo, 1987, pp. 73-76).

2) Compositional analysis: In his analysis of Echave Orio’s paintings La porciúncula and La oración en el huerto Francisco Gatica (2006) discovered the artist’s use of “structural geometry” to define light and background planes all brought together in a creative golden composition (Wade, 2017, p. 76-81).

Procedure: In order to locate the compositional lines that the author of this painting must have drawn, a photograph of the painting was imported to the Adobe Illustrator® vectorial design program, a graphics editor that like an art studio works on a drawing panel. The lines of the digital illustration revealed both the divine proportion and the main lines and figures that make up “the skeleton” of the La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís (Figure 7). Two vanishing points that constitute a rhomboidal grid were found. The first one is related to the Seraphic Christ (dark blue lines), while the second is related to the Sun announcing the blushing rays of the dawn (light blue lines). It was placed at the center of the image, which corresponds to the stigma in the heart of Saint Francis (red dot), from which two main axis are derived: one supports friar León's line of sight, and the other, the flow of the river (light blue lines). Secondary diagonal axis were also found in the painting to support the anatomy of the Saint- the position of his hands, the position of his leg and flexed knee (yellow lines). The two-dimensional space of the Holy Man of Assisi was measured with a triangular shape (red lines). Based on the equivalence of the golden section (1.618 or phi), a golden rectangle was drawn (black lines) that divided the painting into 16 fractions (green lines); on the left side of the painting, however, the part with friar León stood out on account of the modification made by the artist according to the engravings of Maerteen de Vos (1584) and Camilo Procaccini (1593), for the sake of following the narrative of The Little Flowers of Saint Francis. The painting closely adheres to rhetoric and invention, the characteristics that distinguish the works of Baltasar de Echave Orio (Cuadriello et al., 2018, pp. 13-20).

(Composition: David Alberto Flores Rosas, 2016; ECRO, Mexico)

Figure 7 Analysis of compositional lines in La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís, to find the golden section.

3) Digital radiological analysis: Considering the principles of the classic geometrical concepts used by Pacioli (1509) in De divina proporzione -illustrated by da Vinci- to represent ideas clearly and harmoniously by means of the divine proportion (Wade, 2017, pp. 76-81), we revisited the results of the studies done on da Vinci’s painting Annunciation, which discovered a triangular network, suggesting the manner the drawing was transferred on to the primer (Dunkerton, 2011, pp. 4-31). Also considered important were the radiological results of El martirio de san Ponciano because this painting -kept in the Museo Nacional de Arte of the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura (INBAL)- bears the signature of Baltasar de Echave Orio. These results mention diagonal incisions that were interpreted as scoring on the wood panel to affix the lining panel (Cuadriello et al., 2018, p. 104). This is the first layer described in European art treatises in the manufacture of painting on wood panels. Finding a similar geometric grid on La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís would reaffirm our hypothesis about the importance Baltasar de Echave Orio and his studio assigned to compositional analysis, drawing, and the divine proportion.

Procedure: Our test was done in situ, and the factors prescribed by specialists to radiate the painting were the following: electric flow in milliamperes (mA), energy of the current in kilovolts (kV), and exposure in seconds (s). The X-ray images (reserved for the thesis from which a fragment is used in this academic report) pointed to what had been noted in the previous two stages of the study: the composition and transfer of the sketch were accomplished by scoring several lines that allowed the artist to project his idea (Figure 8). Such lines were identified in the color photograph of the painting, while the lines observed in the X-rays were followed using a vectorial program and resulted in an equidistant rhomboidal grid.

Golden section: conclusions

The methodology applied in La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís reveals the work of an academic artist in the European tradition (Garrido y Alba, 2006, pp. 20-40) who settled in New Spain.

Compositional analysis is part of the creative process in this painting. The artist scored a rhomboidal grid into the primer that was inalterable once covered by brush strokes of color. As described in European treatises this process was known as “making the scratches” (Carducho, 1633, p. 133). The expertise of the painter is apparent because there were no changes in the final composition, as confirmed by IR photographs (reserved for the thesis from which a fragment is used in this academic report). Friedrich Hegel conceived artwork as an illusory representation of ideas (Bloch, 1982, p. 265, 282), a symbol attained uniquely by “the powerful collegiality of the artist” with the diagonal lines (visible with X-rays) that in fact allowed the painter to compose his artistic idea, understood by Hegel, as an instrument to further religious faith. The experienced author of this painting achieved the “essential appearance” (Bloch, 1982, p. 258) of his idea when he composed the background planes using harmonic proportions, as previously analyzed by Gatica (2006) and Flores (2007, pp. 25-39) in Echave Orio’s artwork. These lines corroborated that the artist did not want his artwork to provide pleasure alone but, in the spirit of Plato, he also wanted his paintings to convey virtuous values (Alcoberro, 2019, pp. 105-120). The author of La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís sought that same purpose: to use painting to educate and move (Báez, 2009, pp. 171-192).

From the conservator/restorer perspective, these results provide more complete information about the artist’s authorship, and also data about the traditions of his day, which is crucial if art historians in Mexico are to better classify the members of the Echave studio. It should be noted that the procedure explained here is a contribution to research that focuses on the techniques and materials used in the artwork produced in the Echave studio, aiming to provide a deeper understanding of how its artists painted. Noteworthy among these artists are Francisco Ibía, Baltasar de Echave Orio, his son Manuel de Echave Ibía, his grandson Baltasar de Echave de León, his great-grandson Baltasar de Echave Rioja, his student Luis Juárez, and Spanish painter Valerio Cruzate (AGN, 1604). The artistic and historic personality of these artists requires further investigation to understand how they interrelated with each other in their work. Also pending is a detailed analysis of the manufacturing technique in their paintings to determine the influence of Baltasar de Echave Orio in terms of conveying his technical and operational knowledge so the others could create their own paintings.

According to Walter Benjamin (2003/1936, pp. 49-57), contemporary society assigns to traditional artwork a symbolic authority, an “aura”, that industrialized and technological processes, like photography, are incapable of reproducing. For this reason, this painting from New Spain -albeit, anonymous- deserves our recognition and we must value it not only as a work of art -or because its authorship has been “authenticated”- but also because of the results the study of the painting offer in terms of the visuality of its image, the characterization of material and technological resources and the interpretation of deterioration and alteration. Such mechanisms shed information to link the material biography of the painting to the social environment it preserves which, therefore, make it a worthy testimony of the history of Mexico and the world. These different assessments endow objects of this kind with greater significance and constitute a call to Mexican society to be more attentive of the cultural legacy around it, and entrust it to the hands of specialists in conservation/restoration (ICCROM, 2014).

Acknowledgements

To the following Mexican agencies: Museo Regional de Guadalajara (MRG), Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente (ECRO), Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía (ENCRyM), Coordinación Nacional para la Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural (CNCPC), Departamento de Antropología Física (DAF), Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), Laboratorio de Análisis y Diagnóstico del Patrimonio-El Colegio de Michoacán (Ladipa-Colmich), Delegación de Euskadi en México (2013-2017/2017-2021).

REFERENCES

Acidini, C. (2017). Ordine e proporzione: l’ultimo Vasari. En C. Falciani y A. Natali (Eds.), Cinquecento a Firenze (pp. 177-188). Mandragora. [ Links ]

AGN (autor desconocido). (10 de marzo de 1604). [Documento sin título]. Archivo General de la Nación (Instituciones Coloniales, Matrimonios, vol. 333 A, exp. 16), Ciudad de México. [ Links ]

Alcoberro, R. (2019). Platón. RBA Libros. [ Links ]

Alpers, S. (1983). The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century. University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

Arroyo, E., Espinosa, M., Falcón, T. y Hernández, E. (2012). Variaciones celestes para pintar el manto de la Virgen. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, 34(100), 85-117. doi: https://doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.2012.100.2328 [ Links ]

Báez, E. (2009). Historia de la Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes (Antigua Academia de San Carlos) 1781-1910. Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas- Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Bautista, J. (12 de noviembre de 2020). Por qué y para qué se incluye en la curricula de los conservadores las técnicas imagenológicas [Presentación en conferencia]. Coloquio Internacional Lecciones ante el tiempo: desafíos en la enseñanza de la conservación profesional. Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente, Guadalajara, Jalisco. https://www.facebook.com/ecro.escueladeconservacionyrestauracion/videos/373527350597343 [ Links ]

Belgodere, F. J. (1969-1971). El retablo de San Bernardino de Sena en Xochimilco. Estudio formal y simbólico-religioso [suplemento 2]. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas , 10(39). doi: https://doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1970.sup2.2470 [ Links ]

Benjamin, W. (2003). La obra de arte en la época de su reporductibilidad técnica (A. E. Weikert, Trad.). Editorial Itaca. (Obra original publicada en 1936). [ Links ]

Brandi, C. (1977). Teoria del restauro. Piccola Biblioteca Enaudi. [ Links ]

Cano, N. (2020). Laboratorio de rayos X: prácticas institucionales aplicadas a pintura de caballete novohispana. Revista CR. Conservación y Restauración, 20(20), 124-133. [ Links ]

Carrillo, A. (1953). Autógrafos de pintores coloniales. Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Carducho, V. (1633). Diálogos de la pintura: su defensa, origen, esse[n]cia, definicion, modos y diferencias. Francisco Martínez impresor. http://bdh-rd.bne.es/viewer.vm?id=0000034318 [ Links ]

Castañeda, M. (2017). Caracterización e identificación del índigo utilizado como pigmento en la pintura de caballete novohispana [Tesis de licenciatura no publicada]. Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente. [ Links ]

Couto, J. B. (2006). Diálogos sobre la historia de la pintura en México. Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Cruz-Lara, A. (2017). Entre lo universal y lo nacional. La formación de la Pinacoteca del Museo Regional de Guadalajara. Antropología. Revista Interdisciplinaria del INAH (3), 18-31. https://revistas.inah.gob.mx/index.php/antropologia/article/view/12981 [ Links ]

Cruz-Lara, A. (diciembre, 2018-marzo, 2019). El retrato de Michelangelo Buonarroti en la colección del Museo de Bellas Artes. Etnografía y enseñanzas artísticas. Gaceta de Museos: Primer centenario del Museo Regional de Guadalajara (72), 8-13. [ Links ]

Cuadriello, J., Arroyo, E., Zetina, S. y Hernández, E. (2018). Ojos, alas y patas de mosca: Visualidad, técnica y materialidad en El martirio de san Ponciano de Baltasar de Echave Orio. Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Dunkerton, J. (2011). Leonardo in Verrocchio’s Workshop: Re-examining the Technical Evidence. National Gallery Technical Bulletin, 32, 4-31. [ Links ]

Esponda, C., y Hernández-Ying, O. (2014). El Arcángel San Miguel de Martín de Vos como fuente visual en la pintura de los reinos de la monarquía hispana. Atrio. Revista de Historia del Arte (20), 8-23. https://www.upo.es/revistas/index.php/atrio/article/view/1941 [ Links ]

FamilySearch. (2021). Balthasar de Hechave in entry for Manuel de Hechave de Ybia, 1587. FamilySearch [Base de datos] (Colección: México, Distrito Federal, registros parroquiales y diocesanos). https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QJ8Y-1TCY [ Links ]

Flores, D. (9 de noviembre de 2017). Contribución de los vascos Francisco de Zumaya y Baltasar de Etxabe Orio en el arte novohispano [Presentación en conferencia]. Tercer Congreso Internacional La Presencia Vasco-Navarra en México y Centroamérica, Siglos XVI-XXI. [ Links ]

Flores, O. (2007). El martirio de san Ponciano de Baltasar de Echave Orio. Un ejemplo de pintura manierista en la Nueva España. Decires. Revista del Centro de Enseñanza para Extranjeros, 10(10-11), 25-39. http://www.revistadecires.cepe.unam.mx/articulos/art10-2.pdf [ Links ]

Garrido, C. y Alba, L. (2006). El trazo oculto. Dibujos subyacentes en pinturas de los siglos XV y XVI. Museo Nacional del Prado. [ Links ]

Garzón, A. (2017). Las florecillas de san Francisco. Palabra Ediciones. [ Links ]

Gatica, F. (2006). Análisis plástico de la obra de Baltazar Echave Orio y Sebastián López de Arteaga [Tesis de licenciatura no publicada]. Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. https://tesiunam.dgb.unam.mx [ Links ]

Ineba, P. (2006). El conocimiento del soporte y del dibujo subyacente por medio de la radiografía y reflectografía de infrarrojo. En Los retablos: técnicas, materiales y procedimiento [Actas de conferencia]. Grupo Español del International Institute of Conservation. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/libro?codigo=400183 [ Links ]

López, L. (2014). El patrimonio artístico y las voluntades de la conservación: Cencropam. En G. Gil, L. López, I. Ramírez, J. Espinosa y L. Cuatecontzi (Eds.), Cencropam: 50 años de conservación y registro del patrimonio artístico mueble: inicios, retos y desafíos. Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes y Literatura/Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes. [ Links ]

Macías, E. (2017). Archivos y procesos creativo-expositivos: una reflexión museológica sobre la violencia en los proyectos recientes de la artista Ioulia Akhmadeeva en Michoacán, México. Intervención. Revista Internacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museología, 8(16), 17-30. [ Links ]

Madrid, Y. y Castañeda, M. (2009-2010). Informe Final Restauración de las Pinturas del Retablo Mayor del Templo de Santo Domingo, Yanhuitlán, Oaxaca [Informe no publicado]. Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía. [ Links ]

Manrique, J. A. (1982). La estampa como fuente del arte en Nueva España. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas , 13(50), 55-60. [ Links ]

Mederos, F., Meza, A., Sainz, M. y Ramírez, C. (2012). Radiología aplicada al estudio de pintura de caballete. En J. Bautista y M. Insaurralde (Coords.). Manual de radiología aplicada al estudio de bienes culturales. Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente/El Colegio de Michoacán. [ Links ]

Meza, A. (2014). Historia del arte y restauración. Un análisis de la interdisciplina en el estudio de la pintura de caballete novohispana [Tesis de licenciatura no publicada]. Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente. [ Links ]

Oropeza, M. (6 de noviembre de 1975). Restauración de colecciones, relación de pinturas que pasan a los talleres del INAH. Archivo Histórico del Departamento de Restauración del Museo Regional de Guadalajara, INAH (Oficio: 401/14/470), Guadalajara, Jalisco. [ Links ]

Pacheco, F. (2001). El arte de la pintura (2ª ed.; H. Bassegoda, Ed.). Cátedra. (Obra original publicada en 1646). [ Links ]

Palomino, M. (2020). Intención, afectos y colorido: la secuencia técnico-pictórica de José de Ibarra [Tesis de licenciatura no publicada]. Escuela Nacional de Conservación, Restauración y Museografía-Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [ Links ]

Pascual, A. y Rodríguez, A. (2015). Vicente Cartucho: Dibujos. Catálogo razonado. Centro de Estudios Europa Hispánica. [ Links ]

Pérez, M., Arroyo-Lemus, E., Ruvalcaba-Sil, J. L., Mitrani, A., Maynez- Rojas, M. Á. y Lucio, O. G. de. (2021). Technical non-invasive study of the novo-hispanic painting the Pentecost by Baltasar de Echave Orio by spectroscopic techniques and hyperspectral imaging: In quest for the painter’s hand. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy, 250. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2020.119225 [ Links ]

Revilla, M. (1893). El arte en México en la época antigua y durante el gobierno virreinal. Secretaría de Fomento. [ Links ]

Ruiz, R. (2004). Nuevo enfoque y nuevas noticias en torno a “los Echave”. En C. Gutiérrez y M. del C. Maquívar (Eds.), De arquitectura, pintura y otras artes. Homenaje a Elisa Vargaslugo (pp. 183-207). Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Sánchez, N. (2015). La restauración de la pinacoteca virreinal del Museo Regional de Guadalajara durante el proyecto de Reestructuración 1973-1976. Principios, criterios, y técnicas de intervención en la pintura sobre lienzo [Tesis de licenciatura no publicada]. Escuela de Conservación y Restauración de Occidente. [ Links ]

Serrano, M., Baptista, M. y Araujo, R. (1976). Ficha clínica de "La estigmatización de san Francisco de Asís". Archivo Histórico de la Coordinación Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural, INAH, Ciudad de México. [ Links ]

Tardito, R. (1993). La tempera alle origini e sino al Settecento. En M. Petrantoni (Ed.), Techniche pittoriche e grafiche. La pittura a tempera e ad olio (pp. 98-107). Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato. [ Links ]

Toussaint, M. (1934). Catálogo del Museo Nacional de Artes Plásticas. Sección colonial. Ediciones del Palacio de Bellas Artes. [ Links ]

Toussaint, M. (1965). Pintura colonial en México. Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Tovar, G. (1979). Pintura y escultura del Renacimiento en México. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. [ Links ]

Tovar, G. (1982). Renacimiento en México: artistas y retablos. Secretaría de Asentamientos Humanos y Obras Públicas. [ Links ]

Tovar, G. (1992). Pintura y escultura en Nueva España (1557-1640). Grupo Azabache. [ Links ]

Vargaslugo, E. (1987). Una pintura más de Baltasar de Echave Ibía. Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas , 15(58), 73-76. doi: https://doi.org/10.22201/iie.18703062e.1987.58.1351 [ Links ]

Victoria, J. G. (1994). Un pintor en su tiempo: Baltasar de Echave Orio. Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas-Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Villa, G. (c. 1973). Reporte de trabajos efectuados en el Museo Regional de Guadalajara durante el año 1973. Archivo Histórico de la Coordinación General del Patrimonio, Universidad de Guadalajara (Exp. 41), Guadalajara, Jalisco. [ Links ]

Villalobos, Ó. (2016). Los estigmas de san Francisco de Asís. Orden de Frailes Menores. [ Links ]

Vinci, L. da. (2013). Tratado de pintura (D. García, Trad.). Alianza. [ Links ]

Wade, D. (2017). Geometría y arte: Influencias matemáticas durante el Renacimiento. Librero. [ Links ]

Wadum, J. (1995). Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) and His Use of Perspective. En A. Wallert, E. Hermes y M. Peek (Eds.), Hi storical Painting Tech niques, Materials, and Studio Practice [Actas de conferencia] (pp. 148-154). The Getty Conservation Institute. [ Links ]

Zuno, J. G. y Razo, J. (1957). Guía del Museo de Guadalajara. Colecciones Centro Bohemio. [ Links ]

Received: September 06, 2021; Accepted: December 03, 2021; Published: December 28, 2021

texto em

texto em