Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Intervención (México DF)

versión impresa ISSN 2007-249X

Intervención (Méx. DF) vol.12 no.23 México ene./jun. 2021 Epub 26-Sep-2022

https://doi.org/10.30763/intervencion.247.v1n23.26.2021

Academic report

Using the Object ID Standard and Tainacan Software for Museum Documentation: experiences from Brazil and Mexico

*Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), México. glo_velasco@hotmail.com

**Universidade de Brasília (UnB), Brasil. dmartins@gmail.com

***Universidade de Brasília (UnB), Brasil. lucianamartins@percebeeduca.com.br

****Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas (IIE), México. claudio.molina.salinas@gmail.com

*****Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM), Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas (IIE), México. angeles.pedro@gmail.com

This academic report describes the implementation process of the Object ID standard using Tainacan, a free open-source software which included four museological institutions from different countries -Brazil and Mexico- as a comparative case study. We considered the hypothesis that the two countries share similarities related to cultural contexts and heritage objects. Therefore, we expected similar results, such as the observed benefits of using a documentation software and a metadata schema. In this case study, we present the results of this investigation, but as will be seen, much remains to be done. As a prospect for the future, we are considering to expand the experiment to other standards, such as the Lightweight Information Describing Objects (LIDO) standard.

Key words: digital repositories; museum documentation; standardized museum documentation; online publication of museum collections; Object ID standard; Tainacan software

Este INFORME ACADÉMICO describe el proceso de implementación del estándar Object ID usando Tainacan, un software gratuito de código abierto, en cuatro instituciones museológicas de distintos países, Brasil y México, como un estudio contrastivo de caso. Consideramos la hipótesis de que ambos países comparten similitudes relacionadas con los contextos culturales y los objetos patrimoniales. Por ende, esperábamos resultados similares, como los beneficios observados de usar un programa de documentación y un esquema de metadatos. En este estudio de caso presentamos los resultados preliminares de una investigación en curso, y como se verá, aún queda mucho por hacer. Para el futuro estamos considerando ampliar el experimento a otros estándares como el Lightweight Information Describing Objects (LIDO).

Palabras clave: repositorios digitales; documentación de museos; estandarización de la documentación de museos; publicación en línea de colecciones de museos; estándar Object ID; software Tainacan

Introduction

Object ID is an international standard for the description of cultural heritage. Its goal is to provide the necessary information to identify stolen works of art and antiques, by including descriptive metadata elements. This standard is also use-ful as an international reference, with the ability to ensure data consistency, interoperability, and integration between different collections and institutions (Thornes, 1995).

In the following case study, Object ID is regarded as a standard which offers a strategy to improve the quality of museum documentation in four museological institutions in two countries: Brazil and Mexico. We believe that its application and use stimulate a more self-reflective practice on the part of museum professionals, by highlighting the significance of documentation policies.

Object ID is widely known throughout the world and Mexico is no exception. Beyond the knowledge by committed members of the Mexican museological community, we find institutional initiatives, such as the Manual para la elaboración de una ficha de identificación de un bien cultural (CONACULTA, INAH, & CNCPC, n.d.) in which the standard was taken as a reference to draft a cataloging best practice manual. It specified the following: “Los datos requeridos están basados en el formato del Object ID, del Getty Information Institute’’1 (CONACULTA, INAH, & CNCPC, n.d., p. 23). However, as will be seen in the two Mexican examples analyzed, it would appear that the application of this standard is not very widespread.

On the other hand, although the Object ID standard has also been widely disseminated in the Brazilian context, and there exists a broad discussion about the importance of using metadata standards, no cases have been identified where museums use Object ID as their cataloguing standard.

This research is focused on the use of the free, open-source Tainacan software2 (Tainacan Project, n.d.). The tool was developed in Brazil and adopted by Mexican institutions for the management and promotion of digital collections based on WordPress.

Given that the Tainacan project is in the process of internationalization, its use in Mexican museological institutions is still at a testing and consolidation stage; however, in Brazil, the software has already been downloaded over 7 million times (Tainacan Project, 2021a) and has been adopted by the Instituto Brasileiro dos Museus (Ibram, its acronym in Portuguese) as a software to be considered in public policies for the museological sphere, as well as among other Brazilian museums and cultural institutions (Tainacan Project, 2021b). To date, Tainacan has proved to be a user-friendly software for collection management and the documentation practices of cultural heritage institutions.

Finally, the input of this research lies in interlinking Tainacan, Object ID, and Dublin Core . Regarding these last two standards, they were used as the basis for defining a metadata schema, able to meet the needs of Brazilian and Mexican institutions vis-à-vis the Tainacan software.

Brazil and Mexico: two scenarios on documentation culture

In January 2020, teams from the Universidade de Brasília (UnB, its acronym in Portuguese) and the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM, its acronym in Spanish) began a research project with two main objectives: firstly, to improve the documentation practices in the museums of their respective countries; secondly, to provide them with an adequate tool to begin disseminating their collections online. For a long time, both teams shared the intuition that the museums of Brazil and Mexico presented similar conditions, which could be summarized as follows:

compelling necessities (limited or very tight budgets and few staff dedicated to documentation or cataloging of objects and collections);

growing interest in publishing online catalogs;

limited knowledge and experience in the field of Information Technology (IT) and its application in documentation tasks, and

the need to promote a better documentation culture.

The aforementioned panorama requires actions to:

find applied solutions for the creation of online catalogs (based on best practice), and

encourage technological solutions, even under adverse conditions.

Since documentation problems do not depend on the use of a specific technology, we propose the adoption of the Tainacan software, in conjunction with the Object ID standard, as a possible solution to the challenges described above.

We sustain that such a standard is more than just a metadata schema, for it raises awareness on best practice in museum documentation. Consequently, it plays an important role in the protection of cultural heritage. In relation to Tainacan, we would like to highlight its philosophy; it seeks to offer affordable and adequate information technologies with minimal resources.

We believe that the Object ID-Tainacan duet could work like a “Swiss army knife” for the Latin American museum context. Among the main benefits we identified are the online publication of museum collections and the improvements to museum documentation. Additionally, the knowledge representation provided by the Object ID standard should be reflected in the online display of the collection’s items.

One initiative, four museums

The Museo Postal y Filatélico and the Colección Arqueológica of the Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco

Overview

The Mexican museums enrolled in this project were the Museo Postal y Filatélico and Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco (CCUT, its acronym in Spanish), both located in Mexico City but with their own specific characteristics.3

The first one is found in the heart of Mexico City’s historical center, in a beautiful building dating from the early 20th century. By 1907 it had become the headquarters of the National Postal Service, one of the longest-standing establishments in the country. Given the continuously growing collection of postage stamps, documents and various objects related to the postal service, the museum was founded in 1920 to preserve what is nowadays considered industrial-postal heritage.

To this day, the Museo Postal is a public organization under federal administration. Its collection of some 50 000 items is partially exhibited in six rooms, while another two rooms hold special exhibitions. The museum receives an average of 120 000 visitors per year,4 a figure in great contrast to the total number of staff, just fourteen. Among the staff, a librarian oversees the registrar area. Despite the institution’s historic tradition, it inevitably faces several challenges related to collection management and documentation, which will be developed further on.

As for the other museum involved in this project, the CCUT was founded in 2007 by UNAM. It was defined as a “multidisciplinary complex dedicated to the research, study, and promotion of subjects related to art, history and processes of resistance’’5 (CCUT, 2017). The museum is located on the southern side of Tlatelolco square, also known as the Plaza de las tres culturas,6 an emblematic site in the nation’s history.

The museum displays a diverse collection of approximately 52 500 cultural items distributed in different internal collections. For instance, it safeguards the documentary heritage of the art critic Juan Acha, as well as of the Mexican movement of 1968 (m68) (CCUT, 2018), while also including other works of an artistic or archeological nature. The institution offers a wide range of educational and cultural activities aimed at different audiences, and continuously organizes temporary exhibitions supported by a team of 130 people.

During the implementation of this project, three people in charge of different internal collections actively followed the seminars on museum documentation. However, the initiative to promote these activities within the CCUT came from the archeologist in charge of the Archeological Collection (some 15 000 items) and she was strongly engaged in learning the Tainacan software. Therefore, the focus will be centered on her experience and the specific obstacles she faced within her department.

Documentation Challenges in the Mexican Museums

A survey was carried out to know more about the current state of documentation practices and Information Technology (IT) infrastructure in these institutions. The survey structure was based on a previously existing document known as the Cuestionario de diagnóstico para evaluar el nivel de madurez tecnológica en gestión de acervos de los museos de México (Secretaría de Cultura, 2020), designed in the framework of a collaboration between the Tainacan team and the staff in charge of the project Mexicana: Repositorio cultural de México, in 2020. The purpose was to evaluate the degree of technological maturity developed and applied by museums overseen by the Ministry of Culture of Mexico, as part of a preliminary research phase on museum digital collections management.

The survey is divided into seven thematic axes: characteristics of the institution, information management, human resources, it infrastructure, media & communication, institutional management, and governance.

During the survey, the librarian provided information on the Museo Postal collection as a whole, whilst the archeologist only referred to the situation of the CCUT Archeological Collection (henceforth AC). Characteristics of the institution provided general information on the museums, their collections and visitors. Data collected in this part of the survey was used in the previous section to provide an overview of the institutions.

On the subject of Information Management, the Museo Postal indicated 20% progress in their objects inventory, against 26-50% in the case of the AC. The first one reported not having an established documentation system based on metadata standards, nor using any software to record their information. On the other hand, the AC has a FileMaker database; however, this application does not cover the specific needs for the desired collection management. Their electronic records are mainly carried out in Excel, where they organize their inventory, administrative information, and aspects regarding collection management, such as loans (in the case of the AC). Furthermore, the Museo Postal has not carried out any digitization of their items. In contrast, the AC states that 26-50% of their collection has been digitized.

As for Human Resources, there is an average of 4.5 people engaged in documentation practices in both institutions. Moreover, training for staff in this field is sporadic. Albeit staff in the AC present a more specialized profile, people with a university degree in the field of archeology.

Regarding it Infrastructure, the Museo Postal reported a total of nine computers, all of them in good conditions and with high-quality internet connection. Nevertheless, none of these devices is used exclusively for documentation tasks. Additionally, there is not a specific it support team charged with inquiries from the registrar collection area. There is a single team for the entire institution. Another important detail is that they do not have their own online server on which to store and protect their digital information. As for the AC, the situation is quite similar, except for their ownership of an online server.

On the axis of media & communication, it stood out that neither the Museo Postal nor the AC exhibited their collections online. This was one of the strongest motivations to consider the use of the Tainacan software. Nonetheless, both institutions are striving to share and promote their collection on social media, using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Regarding Institutional Management, it is worth noting that both museums are undertaking diverse measures on the issue of digitization of collections, mainly focused on documentation and digitization of objects.

Finally, concerning the issue of governance, the fact that the museums have an independent budget to finance their programs should be highlighted. However, the number of resources destined to keep developing a digital collection plan depends on the degree of interest of the administration in turn.

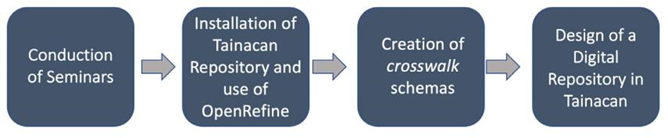

Endure Weaknesses and General First Impressions

A team was formed in June 2020 comprising the librarian from the Museo Postal, the archeologist in charge of the AC and the members of the Unidad de Información para las Artes (UNIARTE, its acronym in Spanish), at the Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas (IIE, its acronym in Spanish) of UNAM. The goal was to provide the museum staff with methodological, practical, and theoretical tools to enhance their documentation practices. The working route, developed over three months of weekly meetings, can be synthesized in the four tasks described below (Figure 1):

(Diagram: Velasco, Lopes, Conrado, Molina & Ángeles, 2021)

Figure 1 Documentation strategy followed by the Mexican museums.

The goals of these four tasks are:

1. Conduction of Seminars. Documentation and Standards: initially, we dedicated a session to explaining the importance of documentation tasks within cultural heritage institutions (Tainacan, 2021a). The seminar considered aspects such as the need for a documentation policy and best practice based on metadata standards. The importance of, and need for, rules and controlled vocabularies to enable interoperability and information retrieval was mentioned (Elings & Waibel, 2007). Another session was committed to studying the information elements of the Object ID standard.

2. Installation of Tainacan Repository and Use of OpenRe-fine: we followed the Tainacan software manual’s installation procedures. We also explained some of its basic features and functions. Additionally, we gave several demonstrations on employing OpenRefine (The OpenRefine Project, n.d.) as a tool for reconciling information from databases (Tainacan, 2021b). As a result, we managed to have a working software installed for each museum, along with a method to clean data and transform it into a single common format.

3. Creation of Crosswalk Schemas: Both museums started to map the information elements of their inventory and cataloging systems into the Object ID metadata schema, with our guidance and support. Subsequently, we started the data mapping from Object ID to Dublin Coretm (The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative [DCMI], 2019). Although dcmi is not a metadata style designed for the description of cultural objects, which Object ID is, its importance lies in the fact that it permits interoperability and information exchange between systems. During this cross-walk phase, the people enrolled in this project were confronted by the challenge of maintaining the richness and thoroughness of their items’ information from one schema to another. The mapping exercise undertaken by the museums is presented next (Figure 2):7

Figure 2 Mapping exercise undertaken by the museums.

| Bublin CoreTM | Object ID | Museo Postal | Archaeological Collection CCUT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contributor | X | ✓ | |

| Coverage | Date or period | ✓ | ✓ |

| Creator | Maker | ✓ | ✓ |

| Date | Date documented* | ✓ | ✓ |

| Description | Description | ✓ | ✓ |

| Materials and techniques | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Inscriptions and markings | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Distinguising Features | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Place of Origin /Discovery* | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Format | Materials and techniques measurements | ✓ | ✓ |

| Identifier | Inventory number* | ✓ | ✓ |

| Language | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Publisher | X | ✓ | |

| Relation | Cross Reference to Related Objects* | X | X |

| Rights | X | ✓ | |

| Source | Related Written Materials* | ✓ | X |

| Subject | Subject | X | ✓ |

| Title | Title | ✓ | ✓ |

| Type | Type of object | ✓ | ✓ |

(Chart: Velasco, Lopes, Conrado, Molina & Ángeles, 2021)

As can be seen, the Museo Postal staff needed to expand their elements of information: contributor, publisher, rights, and subject, to complete the crosswalk to Object ID and Dublin Coretm. Similarly, the AC needed to include source. Finally, both museums needed to include the metadata relation.

4. Design of a Digital Repository in Tainacan: at the same time, museum staff began to design the metadata template in Tai nacan, which would be used to register their items and future online publication. Interesting reflections took place during this process, such as the distinction between information to be kept confidential for internal management and public access information; or dilemmas between the degree of complexity vs. accessibility, and exhaustivity vs. comprehensibility (Roberts, 2004). Proficiency in the knowledge of documentation culture was presented as the key to solving these kinds of doubts on collection management.

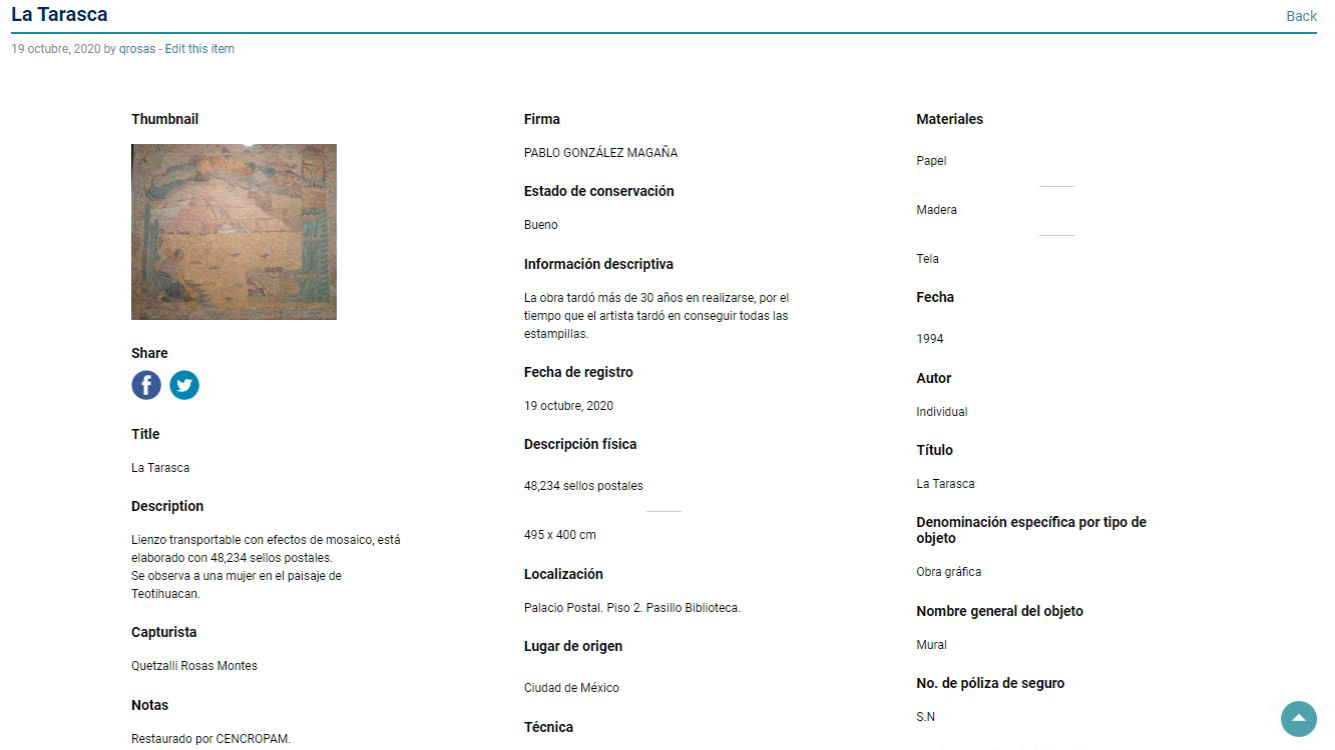

During the implementation process, staff from the museums with the Tainacan interface defined a metadata template and selected the best option for indexing their information amongst the metadata types provided by the Tainacan repository (short text, large text area, date, numeric, selectbox, etc.). Finally, they captured certain items on the software and visualized them as if they were published online, which gave them a better insight into how their digital collections would look. The results can be seen below (Figure 3).

Museu Victor Meirelles and Museu de Arqueologia de Itaipu

Overview

According to the introductory text on its website, the Museu Victor Meirelles (Museu Victor Meirelles, 2020), is linked to the Instituto Brasileiro de Museus (Ibram), under the Ministry of Tourism. It was founded in 1952 in the house where the artist was born in downtown Florianópolis, capital of the State of Santa Catarina.

Throughout its 69 years of existence, the Museu Victor Meirelles has been developing its history and identity. According to its website, the institution: “[…] seeks to respond to the requests from the community and the individuals who visit it to develop their critical vision, feel unique affective experiences, and trace their own artisic paths with a rich and lively aesthetic experience of life”8 (Museu Victor Meirelles, 2020).

The museum’s initial collection consisted of 27 works by the painter, donated by the Museu Nacional de Belas Artes of Brazil, which were later complemented by donations from other institutions and collectors of other works by the painter, his teachers and students, forming a current collection of 237 works produced by more than 80 artists, all of which are digitized and published in the institution’s digital repository.

The Museu de Arqueologia de Itaipu (MAI) was chosen due to the enormous differences between the types of collection, which would allow the project to analyze different situations of documentation of cultural objects. The museum’s history and the characteristics of its collection are presented on its website (MAI, 2020). Briefly, the museum was inaugurated in 1970, a period when the oceanic region of Niterói was undergoing a modernization process and new archeological discoveries were made, such as the site of Duna Pequena. The 1,040 objects in the museum’s collection came from this location. All the objects are documented and available for public access in the digital repository that the museum published online thanks to the Tainacan software.

Documentation Challenges

The research and methodology for analyzing the technological maturity of museums were developed in Brazil, in the scope of the implementation of the Tainacan software for Brazilian federal museums linked to the Ibram (Universidade Federal de Goiás & Ibram, n.d.). Thus, the research was carried out in Brazilian museums in the same way as was done in the Mexican museums, highlighting important results to identify the current technological situation of museums and establish procedures to improve the quality of their documentation. As in Mexico, the survey was divided into seven thematic axes: characteristics of the institution, information management, human resources, it infrastructure, media & communication, institutional management, and governance. Below, we present the summarized result for the two museums that participated in this research. The results were published and are accessible in a technical report available exclusively in Portuguese (Universidade Federal de Goiás & Ibram, n.d.).

The MAI team developed a participatory inventory process with the local community, which represented a positive leap in terms of structuring information management at the museum. The content of this inventory, along with the inventory of archeological pieces, has been migrated to Tainacan. It does not use a metadata standard; it uses a thesaurus for the classification of collections. The collection’s document management was established based on the parameters set out by Ibram’s rules for inventory (2014). In this sense, the museological documentation covers only the basic aspects of description to identify the cultural asset. The same process was applied with videos and photographs. It was not clear whether the documentary process encompassed all stages of the collection’s management. The museum’s collection has almost been digitized completely. There are no pending issues regarding the ownership of images taken of the collection. The museum has poor it infrastructure: although all employees have computers, they are old and problematic; only two are new pieces of equipment. There is no computer dedicated to information management or collections. The internet is only one Mega, to be shared among all the units. It does not own any servers thus files are backed up to an external hard drive.

The Museu Victor Meirelles organized its document management using Tainacan, which was updated in 2019. The process of filling the individual records of the objects is practically completed. The inventory is complete (in Excel spreadsheets). It does not use a metadata standard. It has digitized images of the entire collection, including documents. Some of these images are available on the institutional website (in .png, .tiff, and .jpeg formats). Image rights have been regularized. It has a total of 10 staff working in the museum. Information management is operated by one of them, who is a museologist specialized in collections and document management. The actions are developed collectively by technicians and management, since the team is small. The museum has an it infrastructure with about 26 computers, most of which are old (only six are new). Computers are multitasking, no equipment is dedicated exclusively to information management. It does not own a server. The internet is good and its bandwidth is being expanded (10 mega, via optic fiber). It has outsourced its it support, but it operates within the museum.

As can be seen, both museums had a very fragile documentation infrastructure, without a clear metadata pattern. The use of controlled vocabularies was only present at the mai but without any specific rules or manuals to standardize cataloging actions.

Endure Weaknesses and General First Impressions

The process of working with Brazilian museums followed a slightly different path from what was carried out in Mexican museums, as the Tainacan software has already been implemented in museums since 2018. When the present research began, both museums had already created their digital repository and their updated documentation was available for consultation on internet.

The work carried out to implement the digital repository consisted of four technical stages of treatment of documentation, whose final product was used to carry out the present research of experimenting with Object ID with the museums. These steps consisted of: the migration of the existing database of museum documentation; the conversion of existing documentation to the data model used by the Ibram -a model developed locally for federal museums-; cleaning, standardization and data processing; and finally, the publication of data on the internet. In addition to these four steps carried out by the team, the present research also included a study to map the current data from the documentation of the two museums to Object ID, seeking to highlight their advantages and possibilities of adaptation, and reflect with the museums on the importance of adopting a broader standard in terms of the potential for interoperability and dialogue with other institutions. The steps are detailed below in Figure 4.

(Diagram: Velasco, Lopes, Conrado, Molina & Ángeles, 2021)

Figure 4 Documentation strategy followed by the Brazilian museums.

The goals of these five tasks are explained below:

1. Database migration: the existing documentation of Brazilian museums was stored in outdated systems that are not easily accessible. The documentation from the mai was found in the form of individual Microsoft Word files. The documentation of the Museu Victor Meirelles was found in Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. The data was migrated to an sql (Structured Query Language) database for further processing.

2. Crosswalk to Inventário Nacional dos Bens Culturais Musealizados [INBCM]): in 2014, the Ibram developed a metadata model for the generation of inventories of museological objects, for use by museums. The model is quite simple and only states the fields to be filled in and the meaning of each field. However, it was adopted by the Institute and standardized for all museums under its direct administration. Therefore, to adapt to this new reality, all existing documentation from the two museums was migrated to this new model.

3. Cleaning, standardization, and data processing: with the use of tools such as OpenRefine software and Python scripts, the documentation was cleared of syntactical errors, and standardized along with the terminology used to index museum objects, according to the terms in the Thesauros para acervos museológicos (Ferrez & Biachini, 1987), developed in Brazil.

4. Publication in Tainacan: once the data was organized, it was published in a digital repository using the Tainacan software. The results can be seen in Figures 5 and 6.

(Image: Velasco, Lopes, Conrado, Molina & Ángeles, 2021)

Figure 5 Example of a museum object documented at the Itaipu Archeology Museum.

(Image: Velasco, Lopes, Conrado, Molina & Ángeles, 2021)

Figure 6 Example of a museum object documented at the Victor Meirelles Museum.

5. Experimental crosswalk to Object ID: the mapping carried out sought to reference the fields used in the documentation of each museum with the descriptions provided by Object ID. There was a noticeable common nucleus that served both museums equally, but the Museu Victor Meirelles seemed to adapt better to the Object ID model than the mai. This is possibly due to the curatorial focus of each museum, with Museu Victor Meirelles being more focused on paintings and works of art than archeology, which seems to be closer to the type of objects on which the Object ID model is based.

Preliminary results

Mexican Case Conclusions

In the Mexican case, the Cuestionario de diagnóstico para evaluar el nivel de madurez tecnológica en gestión de acervos de los museos de México revealed a series of shortcomings and challenges for collection management faced by both institutions. For instance: the ongoing process of carrying out a collection inventory; the need for cataloging and documentation guidelines based on metadata standards, combined with the use of a specialized software able to cover the information requirements of a cultural heritage collection.

Despite the existence of certain it setbacks, such as the lack of a private server, or an exclusive computer for documentation purposes, there are initiatives to develop a digital collection program. There is no doubt that there has been an increased call for online exhibitions during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the physical space of heritage institutions has been restricted. As a parallel reflection, it is possible to envisage a future demand for a cultural heritage expert familiar with documentation (a domain usually regarded as exclusive to librarians), computer sciences, and also knowledgeable on digitization.

The museum staff are now more aware of the priority of standardized documentation within their museums and how this practice is fundamental to collection and exhibition management. In relation to the Tainacan software, they concurred that it is a user-friendly tool with various benefits that could be useful for information interoperability between the different collections of the CCUT and the Museo Postal. Its attractive visualization was another advantage.

In May 2020 we could not assure that the weekly meetings would yield useful results; however, we can say that it was the correct strategy, since we have the following results in both cases regarding the museums:

Sound understanding of the revised standards and the importance of systematized documentation for museums.

Confidence on the use and installation of the Tainacan software on the part of museum staff.

Assessment of the use of OpenRefine to reconcile their databases.

Training to elaborate crosswalks their own metadata schemas to Object ID and Dublin Coretm.

Successful graphic design of a repository and publication.

We wish to point out the interoperability and free, open-source software characteristics, because they provide a certain autonomy in controlling a database, online collection, or inventory. On the other hand, both museums reported encountering problems with software installation. This can be explained by the minimum processor characteristics required to install the program. The potential scope of this tool has yet to be explored.

Figure 7 Tainacan’s mapping exercise.

| Museo Victor Meirelles | Itapu Archeology Museum | Object ID |

|---|---|---|

| Registration number | Registration number | Invetory number |

| Classification | Classification | Type of object |

| Title | Title | |

| Author information | Maker | |

| Production country | ||

| Production brazilian state | ||

| Production city | ||

| Production date | ||

| Materials / Technique | Materials / Technique | Materials and Techniques |

| Dimensions | Measurements | |

| Marks / Inscriptions | Inscriptions and markings | |

| Conservation state | Conservation state | Date period |

| Acquisition mode | Acquisition mode | |

| Provenance | Provenance | Place of origin / Discovery |

| Acquisition date | Acquisition date | Date or period |

| Other numbers | ||

| Denomiation | ||

| Donor | ||

| Descriptive summary | Description | |

| Numbers of parts | ||

| Dating | ||

| Current location | ||

| Form compilation date | Date documented | |

| Width (cm) | Measurements | |

| Thickness (cm) | Measurements | |

| Lenght (cm) | Measurements | |

| Weight (g) | Measurements | |

| Raw material | ||

| Curatorial processes | ||

| Comments | ||

| Hsitoric | ||

| Cataloging Proyect | ||

| Situation | ||

| Copyright |

(Chart: Velasco, Lopes, Conrado, Molina & Ángeles, 2021)

Brazilian Case Conclusions

The work process with Brazilian museums demonstrated strong collaboration and support in the initial stages of the process, with museums very interested in migrating their current solutions for organizing documentation to a digital repository available for free access online. The museologists of both institutions were extremely helpful and acted decisively in partnership with the project team to understand documentation in the standardization, cleaning, and data treatment stage.

Tainacan was valued as a work element that facilitated the production and updating of museological documentation when launching digital repositories.

Regarding comprehension of a new metadata standard and its potential use to promote interoperability, the question still seems distant from the reality of professionals and less concrete in terms of the daily benefits the effort to migrate the data model could provide.

The Object ID pattern seemed to work better for mapping the collection of a museum whose content dialogues more directly with the art world than an archeological one. This seems a fundamental point to grasp in future studies, as there is a vast diversity of museological collections within the museums of the Ibram, such as religious art and folklore, hence it will be of great significance to adopt a pattern that dialogues more widely with this variety of collections.

General Conclusions and Actions for the Future

In sum, this project has demonstrated the desirability of expanding the collaborative network between Brazil and Mexico, since the strengths of one part benefit the whole, that is to say: in Mexico, we have taken advantage of the diagnostic methodology of technological maturity and the technologies developed by our counterpart; while in the case of Brazil, a work path was opened related to the management of metadata standards and the culture of museum documentation. This experience will surely contribute to our project having a Latin American scope.

In Mexico, the use of Tainacan is recent and, therefore, the work began by designing the characteristics that the repositories would have, including the modeling of metadata. For its part, the Brazilian case already had a couple of years of work, and the approach was different, focusing on converting the existing data model to one “compatible” with Object ID. Finally, in both cases, emphasis was placed on refining the data and using thesauri to refine the information.

As actions for the future or possible lines of research, we believe it would be useful to delve into:

The need for wider debate and evidencing of the importance of interoperability of digital repositories for museums. If a museum understands the value of this strategy, it will appreciate it, and will have greater opportunities to expand its audiences, giving its cultural objects greater visibility.

Promote cataloging and counteract the problem of illicit trafficking of cultural heritage, where it exists, with the recovery of the documentation strategy introduced by Object ID.

Promote scholarly programs that professionalize museum documentation.

Figure 8 Tainacan’s mapping exercise (in extenso). Mapping exercise undertaken by the museums in Mexico.

| Meta standar | Description | Meta standar | Description | Museo Postal | CCUT, Archeological Collection | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dublin CoreTM | Object ID | ||||||

| Contributor | An entity responsable for making contributions | What was the abject made of? | X | ✓ | Registrar (agent) / Cataloger (agent) | ||

| Coverage | The spatial or temporal topic of the resource, the spatial applicability of the resource, or the jurisdiction under wich the resource is | Date or period | Do you know who made the object? | ✓ | Date: year, century of period | ✓ | Spatial: Cultural área / región / temporary, epoch |

| Creator | An entity primarly responsable for making the object | Maker | The date on wich the description of the object was made | ✓ | Author: Individual, gropuo or company | ✓ | Historiacl context |

| Date | A point of periodo d time associated with an evento in the lifecycle of the resource | Date Docuemented* | The date on wich the description of the object was made | ✓ | Creation date: year, century of perody / Date of Access to tje collection / Date of registry | ✓ | Registrar date / Last update |

| Description | An account of the resource | Description | Further information to help identofy the object | ✓ | Collection / locatization / conservation satate / marks and signatures / inscriptions / additional notes | ✓ | Technical description / formal description / interpretative description / Decorative motifs / conservation state / notes / registration numbers / marks / inscriptions |

| Materials and techniques | Does the object have any physical characteristics the cloud help to identify it? | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Inscriptions and markings | Are there any identifying markings, numbers of inscriptions on the object? | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Distinguising features | Does the object have any physical characteristics the cloud help to identify it? | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Place of Origin / Discovery* | The name of the place where the object was made or, in the case of archeological finding, the location where it was | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Format | The file format, physycal médium, or dimensión of resource | Materials and techniques | What materials is this object made of? | ✓ | Object type: general and especific name given to the object / materials / techniques / measures or dimensions | ✓ | Dimensions / measurements |

| Measurements | What is the size and /or weight of the object? | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Indentifier | An unambiguous reference to the resource withi a given context | Unventory number | Catalogue numbers or registration numbers | ✓ | System numbre: administrative inventory numbre, national inventory number, insurance policy number | ✓ | Identifier: DRPMZA number (prefered) |

| Language | A language of the object | ✓ | Language | ✓ | Language of the publication | ||

| Publisher | An entity responsable for making the resouce | X | ✓ | CCUT-UNAM | |||

| Relation | A related resource | Cross reference to Related Objects | The historical interest of some objects may partly result from the relationship to other objects | X | X | ||

| Rights | Information about rights held in and over objects | X | ✓ | According the case | |||

| Source | A related source from wich the described resource is derived | Related written material* | This category provides references, inclunding citations, to other written materials related to the object | ✓ | Referencial bibliography | X | |

| Subject | The topic of the resource | Subject | What is pictured or represented? | X | ✓ | Work type 1 | |

| Title | A name given to the object | Title | Does the object hace a little? | ✓ | Previus and alternative titles | ✓ | Principal and alternative |

| Type | The nature or gender of the object | Type of object | Whay type of object is it? | ✓ | Object type: general and specific characteristics | ✓ | Work type 2 |

(Chart: Velasco, Lopes, Conrado, Molina & Ángeles, 2021)

REFERENCES

Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco. (2017). Sobre el CCUT. Cultura UNAM. Recuperado de https://tlatelolco.unam.mx/sobre_ccut/ [ Links ]

Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco. (2018). M68 Ciudadanías en Movimiento. Recuperado de https://m68.mx/ [ Links ]

Elings, M. W. y Waibel, G. (2007). Metadata for all: Descriptive Standards and metadata sharing across libraries, archives and museums. First Monday 12(3). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v12i3.1628 [ Links ]

Ferrez, H. D. y Bianchini, M. H. S. (1987). Thesauros para acervos museológicos. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Cultura/Secretaria do Patrimônio Histórico e Artístico Nacional/Fundação Nacional Pró-Memória: Coordenadoria Geral de Acervos Museológicos. [ Links ]

Instituto Brasileiro de Museus (1 de septiembre de 2014). Resolução Normativa No 02, de 29 de agosto de 2014. Diário Oficial Da União, 1-6. [ Links ]

Museu de Arqueologia de Itaipu. (2020). Museu de Arqueologia de Itaipu. Recuperado de http://museudearqueologiadeitaipu.museus.gov.br/pagina-principal/historico-do-museu [ Links ]

Museu Victor Meirelles. (2020). Museu Victor Meirelles. Recuperado de http://museuvictormeirelles.museus.gov.br/o-museu/historico/ [ Links ]

Noval, B. (s.f.). Manual para la elaboración de una ficha de identificación de un bien cultural. México: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes/ Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia/Coordinación Nacional de Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural. [ Links ]

Roberts, A. (2004). Inventories and Documentation. En P. Boylan (Ed.), Running a Museum: A Practical Handbook (pp. 31-50). París: International Council of Museums. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Cultura. (2020). Mexicana 2020: Hacia una gestión descentralizada de acervos. Cuestionario de diagnóstico para evaluar el nivel de madurez tecnológica en gestión de acervos de los museos de México. México: Secretaría de Cultura/Dirección general de Tecnologías de la Información y Comunicaciones. [ Links ]

Tainacan Project. (s.f.) Install and Setup. Recuperado de https://tainacan.github.io/tainacan-wiki/#/install [ Links ]

Tainacan Project. (s.f.). Tainacan Wiki. The Tainacan Project. Recuperado de https://tainacan.github.io/tainacan-wiki/#/?id=tainacan-wiki [ Links ]

Tainacan. (2020). Cultura da Documentação e Object ID [Video en línea]. Recuperado de https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PXp4RC_ydHk&ab_channel=Tainacan [ Links ]

Tainacan Project. (2021a). Tainacan [Panorama Avançado]. The Tainacan Project [Blog]. Recuperado de https://br.wordpress.org/plugins/tainacan/advanced/ [ Links ]

Tainacan Project. (2021b). Casos de Uso - Tainacan. The Tainacan Project. Recuperado de https://tainacan.org/casos-de-uso/ [ Links ]

The Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. (2019). DCMI: DCMI Metadata Terms. Dublin Core Metadata Initiative. Recuperado de https://www.dublincore.org/specifications/dublin-core/dcmi-terms/ [ Links ]

The OpenRefine Project. (s.f.). OpenRefine. Recuperado de https://open-refine.org/ [ Links ]

Thornes, R. (1995). Protecting Cultural Objects Through International Documentation Standards: A Preliminary Survey. Los Ángeles: University of California, The J. Paul Getty Trust. [ Links ]

Unidad de Información para las Artes. (2020). Unidad de Información Para Las Artes Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Recuperado de http://www.esteticas.unam.mx/uniarte [ Links ]

Universidade Federal de Goiás e Instituto Brasileiro de Museus. (s.f.). Plataforma acervo: inventário, gestão e difusão do patrimônio museológico. Relatório referente ao produto 1 do segundo termo aditivo do TED UFG e Ibram -Mapeamento do nível de maturidade tecnológica dos museus do Ibram. Recuperado de https://pesquisa.tainacan.org/relatorios/produto-f-mapeamento-do-nivel-de-maturidade-tecnologica-dos-museus-do-ibram/. [ Links ]

1“The required data is based on the Object ID format of the Getty Information Institute”. Translation by the authors of the Guide for doing an identification record of a cultural object (editorial translation).

2Tainacan is a powerful, flexible open-source digital repository platform for Word-Press. It can manage and publish digital collections just as easily as posting on a blog, having all the tools of a professional repository platform. It can be used for the creation of a digital collection, a digital library, or a digital repository for your institutional or personal collection (Tainacan Project, n.d.).

3The information employed to draw the general overview of the Mexican museums was taken from the text: Mexicana 2020: Hacia una gestión descentralizada de acervos. Cuestionario de diagnóstico para evaluar el nivel de madurez tecnológica en gestión de acervos de los museos de México (Diagnostic Questionnaire to Evaluate the Level of Technological Maturity in the Management of Museum Collections in Mexico, editorial translation) (Secretaría de Cultura, 2020), which will be explained later on. In this case, the concept madurez tecnológica (in English, technological maturity) is related with the digital transformation and how quickly and effectively an institution can handle this transformation.

4However, this number does not consider all the rooms in the museum and is mostly based on attendance to other kinds of activities. The aforementioned figure was obtained through the application of a the technological maturity survey. This will be explained in-depth in the following section.

5In Spanish: “complejo multidisciplinario dedicado a la investigación, estudio, análisis y difusión de los temas relacionados con el arte, la historia y los procesos de resistencia”.

6It is a place where three different architectural ensembles converge, icons from different historical stages: Mesoamerican, Colonial and Modern. On October 2nd, 1968, the square was the scene of violent military repression against students, during the Mexican movement of the same year.

7The complete information is presented in the final chart (Figure 8).

Received: December 18, 2020; Accepted: April 06, 2021; Published: June 28, 2021

texto en

texto en