Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Diálogos sobre educación. Temas actuales en investigación educativa

versión On-line ISSN 2007-2171

Diálogos sobre educ. Temas actuales en investig. educ. vol.11 no.20 Zapopan ene./jun. 2020 Epub 04-Abr-2021

https://doi.org/10.32870/dse.v0i20.599

Thematic axis

Communicative hegemony, participation, and subordinate voices: notes from the classroom with Wichi children

1 Doctora en Filología (Lingüística). Centro de Estudios del Lenguaje en Sociedad (CELES). Universidad Nacional de San Martín-CONICET. Argentina. vir.unamuno@gmail.com

This article is part of ethnographic and multisite research work that seeks to give an account of the educational practices categorized by their actors as bilingual and intercultural in the El Sauzalito region (Chaco, Argentina), where Wichi girls and boys are educated. In this case, the study focuses on the children's perspective on the contexts and practices of which they are part. To do this, I have taken as my axis of analysis the study of situated participation and interactive embodied actions (Goodwin, 2000, Goodwin & Goodwin, 2004). As I will argue here, the analysis of the movements, looks and gestures of the participants could allow us to reconstruct some of the meanings of the activities they embody, providing us with data that would help us understand the processes of communicative hegemony and the resistance to it through the subordinate voices operating in the cases analyzed.

Keywords: communicative hegemony; participation; Wichi; Chaco; Argentina

Este artículo se enmarca en una investigación etnográfica y multisituada que busca dar cuenta de las prácticas educativas categorizadas por sus actores como bilingües e interculturales, en la región de El Sauzalito (Chaco, Argentina) en donde se escolarizan niñas y niños wichi. En este caso, el estudio se centra en la perspectiva de los niños sobre los contextos y las prácticas de los que forman parte. Para ello, tomo como eje de análisis el estudio de la participación situada y de las acciones interactivas corporizadas (Goodwin, 2000; Goodwin y Goodwin, 2004). Según se argumentará aquí, el análisis de los movimientos, las miradas y los gestos de los participantes permitirían reconstruir algunos sentidos sobre las actividades que ellos encarnan. Esto, en definitiva, ofrecería datos para entender los procesos de hegemonía comunicativa y la resistencia a través de voces subalternas que operan en los casos que se analizan.

Palabras clave: hegemonía comunicativa; silencios; wichi; Chaco; Argentina

Introduction

This research work originated in a challenge to make an ethnographic approach to the perspective of Wichi children on the speech events in which they participate within the schools where they are educated. It has not been an easy task, especially because my research work focuses on processes that, although they involve this group of children, view them mostly through the eyes of their teachers. However, I have tried to shift the focus of my observation by following the traces left by the children on the ways in which they understand what is happening, and taking into account some clues that allow me to approach their perspective on what is said and what is left unsaid in these environments. Such traces and clues are diverse and scattered through different materializations: facial expressions, looks, movements, words and silences. Trying to endow them with a meaning has led me to build an eclectic narrative that I hope can be understood as a jigsaw puzzle: a journey through different pieces that is oriented towards a common image.

I will start by introducing the context in which we worked and briefly describing the approach adopted in this paper, based on the study of participation. I will then analyze some classes to illustrate different aspects of the children’s perspective on the situations in which they participate at school, and finally outline some conclusions.

The context in which we work

Wichi communities are spread over a vast territory from the south of Bolivia to the province of Chaco in Argentina. They are mostly located along two rivers, the Bermejo and the Pilcomayo. The Wichi are the ancestral inhabitants of these lands. Unlike other native groups in Argentina, the still speak their own language, which has been transmitted continuously from one generation to the next.

Several reasons have been put forth to explain the strong vitality of the Wichi language. One is that most of the Wichi population lives in rural areas and is to some degree isolated from urban centers where Spanish is predominant. It has also been argued that among the Wichi the transmission of their language is linked to their own linguistic ideologies and worldview, and that it plays a major role in their processes of identity and construction of ethnical belonging, as well as in their native cosmogony (Unamuno & Romero-Massobrio, 2018).

For some decades now, the Wichi language has also been present in their schools (Zidarich, 2001). Different experiences from diverse approaches of what could be called bilingual and intercultural education have been taking place in the Wichi territories. Their aim is usually to promote literacy in the Wichi language and its use as a linguistic and intercultural resource for the construction of knowledge in Spanish in the schools. There have also been educational experiences that seek to establish a dialog with Wichi cultural practices and knowledge and incorporate them into the children’s schooling.

In the province of Chaco, where we work, bilingual and intercultural educational experiences have increased in the last decade. This has been linked on the one hand to changes in linguistic-educational policies in that province, and on the other to the creation of a center for the training of Wichi teacher in the town of El Sauzalito: the Center for Research and Training in the Native Language Mode (CIFMA, Centro de Investigación y Formación para la Modalidad Aborigen), a pioneering institution in the field of bilingual intercultural education and teacher training in Argentina (Valenzuela, 2009; Valetto et al., 2018).

In the 1990s CIFMA trained the first bilingual assistant teachers, the first Wichi educators who taught in the schools of El Chaco. Then, starting in the early 21st century, Wichi students from El Chaco majored as Intercultural Bilingual Teachers, and then as Intercultural Bilingual Professors (Unamuno, 2013). These three types of Wichi educators are currently working in the schools of the province (Ballena, Romero & Unamuno, 2015).

Regardless of their academic training, Wichi teachers work mostly as assistants. This means that they help linguistically and mediate interculturally in classes taught by a non-indigenous teacher we will call, as it is done in this area, a “white teacher”. Most of these white teachers do not speak or understand the Wichi language. However, they are in charge of the classes and schooling processes of Wichi children.

Wichi educators assume different roles in the schools. As mentioned, most work as assistant teachers. However, the role they perform in the classroom depends on the type of school where they work. As a study by our team (Ballena, Romero & Unamuno, 2015) revealed, besides fulfilling the role of assistants Wichi teachers may also a) be in charge of a class; b) be in charge of a special curricular space usually known as “Wichi language and culture”; c) be in charge of some curricular classes in formats known as “shared classrooms”.

In most cases, Wichi teachers work in initial education (kindergarten) and in the first courses of elementary school. This can be explained to some extent by the prevailing mode of bilingual education in the area and in Argentina at large. By this we mean the transitional model of bilingual education that categorizes an indigenous language as a bridge for the acquisition of linguistic and school knowledge in general in the predominant language. According to this rationale, the use of their native language acquires meaning because it participates in the construction of school knowledge in Spanish.

Following this line of thought, the role of Wichi educators is often limited to a translation of the classes taught in Spanish by “common” (not bilingual) teachers, or to a linguistic mediation between the contents of the curricula - in Spanish - and the children. Even today the experiences that strive for an alternative model of intercultural bilingual education or for models aimed at revitalizing or broadening the domains in which the native language is used have been few and far between. However, these kinds of models are the ones being discussed now by Wichi educators, who seek to introduce in the schools their own perspectives on the curricula and the teaching and learning modes.

The children’s participation as a resource for the construction of meaning

In this context, it might be interesting to inquire into the ways in which the Wichi children give meaning to the school experiences in which they participate. To do this I would like to share both field notes and transcriptions of classes, and analyze them in the light of the study of participation embodied in the framework of ethnography as a method.

I understand participation as a situated process that takes place within a specific time frame and in a physical environment, actively negotiated and reshaped by its participants through corporeal actions (Goodwin, 2000; Goodwin & Goodwin, 2004). In this respect, observations on movements, looks and facial gestures of the participants, which provide clues to reconstruct the meanings of the activities they embody, are relevant. Also relevant are the categorizations on the ways in which the interactions are organized and take place. By this I mean specifically the uses of different languages, but also other aspects of interaction such as the volume of the speech, for instance.

My interest in studying participation in this kind of environment stems from something that emerged in the field and that ethnographic work has enabled me to contextualize: the times when non-indigenous teachers have described Wichi children as “quiet and shy”, as well as the times they have pointed out that they do not participate in the class. However, as I could reconstruct in these years, that description does not correspond with the way in which they behave before me in the classrooms, nor does it correspond with how I usually describe them in my field notes. This leads me to believe that the description made by the non-indigenous teachers may be linked to the ways in which they position themselves before the Wichi children, and to the ways in which they make sense of what they do and say in the classrooms. Therefore, in my analysis, the description of the Wichi children as “quiet and shy” might be interpreted as a symbolic production associated to indigenous people, based on the quieting of their voices. The “silent” is proposed, as well as a social construction linked to communicative hegemony (Briggs, 2005) deployed in the classroom with indigenous children. Etnography, I believe, may help with its method to describe it and interpret the ways in which it works.

My interest in studying participation also lies in my concern about the possibilities and the limits that children have to interact in school environment and, through it, rearrange their knowledge and their speech repertoires. This is part of a broader concern about the role of language in the access to basic rights for the indigenous population in my country.

In order to analyze this, I will take into account the data yielded by extensive and multi-situated ethnographic work; that is, work that seeks to understand a complex situation through the study and analytic comparison of several cases. In particular, I will take into account a set or corpus of classes recorded on video and partially transcribed, as well as the fieldwork notes I have been writing since 2010. All these records have, through an ethnographic approach, allowed me to start building interpretations based not only on what is said but also, and more importantly, on what is done (and what is done both by saying it and by remaining silent). Quoting Julieta Quiros (2014: 51):

Ethnographic experience shows that this “telling us” is in no way literal: people tell us (how they are and how the world works) through what they say, but also and in a more fundamental way through what they do, how they do it, what they do not say, and - as the pragmatists of language have taught us - what they do, willingly or unwillingly, by saying what they say.

Walking through the classrooms

An important element in the construction of the sociolinguistic ethnography I have been practicing lies in doing extensive work on the ground; specifically, in my case, in the classrooms with Wichi children. For almost a decade now, I have shared classes and educational experiences in which they are schooled, and participated both as an educator and a researcher in different projects led by indigenous educators. Thus, between 2012 and 2015 I worked in several experiences at a kindergarten in the town of El Sauzalito. At the same time, I also participated in several projects in the neighboring towns of Tres Pozos (2012 and 2013) and Los Lotes (2015 and 2016).

Likewise, as part of a CIFMA project aimed at learning about the situation of its alumni, I visited more than 13 schools in the Wichi territories of the province of Chaco, where I was able to observe and film classes, as well as interview teachers and school administrators.

All this baggage of shared experiences has allowed me to reconstruct a sort of popular wisdom that goes around classrooms and materializes in the practices I observe and analyze. Through this knowledge of the terrain and by identifying the different positions and theories about the world that coexist (and dialog or argue the popular wisdom), I have tried to build interpretations rooted on the particular study of the ways in which the discourses and subjects are materialized. To do this, the analytical tools of discourse and interaction analysis have been very useful (Fairclough, 1995; Gumperz, 1982).

For this research work in particular, I took into account a selection of fragments or moments of class whose analysis aims to sketch a certain atmosphere that exists in the area where I work, and that allows me to point out some aspects I believe are interesting to account for the children’s perspective on the schools processes in which they participate.

Clementina’s class

The first class I would like to share with you takes place in a kindergarten in the town of El Sauzalito. As is common in this area, the children are separated in two different classes depending on the language they speak (Unamuno & Nussbaum, 2017). In this class, as in most of them, there are two teachers, one of whom is a Wichi teacher and another who is not. Although they are both in the same class, their roles are usually clearly different.

These kindergarten classrooms are the stage of the first instances of school socialization for Wichi children, and are often the first time when Spanish is used in situations in which Wichi children participate.

From a very early age, Wichi children learn bilingual formats of participation. In many of the classrooms, this involves learning to distinguish between moments of the class that take place in a language that they are learning and that therefore seem opaque and others that take place in the language they are familiar with. However, these interactions in the familiar language often occur on the sidelines of the main sequences of the interaction, although they are nevertheless crucial sequences (Unamuno & Nussbaum, 2017).

Estas secuencias laterales parecen pasar desapercibidas desde la perspectiva centrada en la persona adulta. Sin embargo, son fundamentales desde la perspectiva de las y los niños: son ellos quienes muchas veces las inician y las protagonizan.

The class I want to share with you involved 4- and 5-year old children, and was part of a project we conducted in collaboration on the work of Wichi women with clay to make large pots. This project, which culminated recently with the writing of a book of stories and accounts of experiences, included several moments such as the one described in the following transcription.

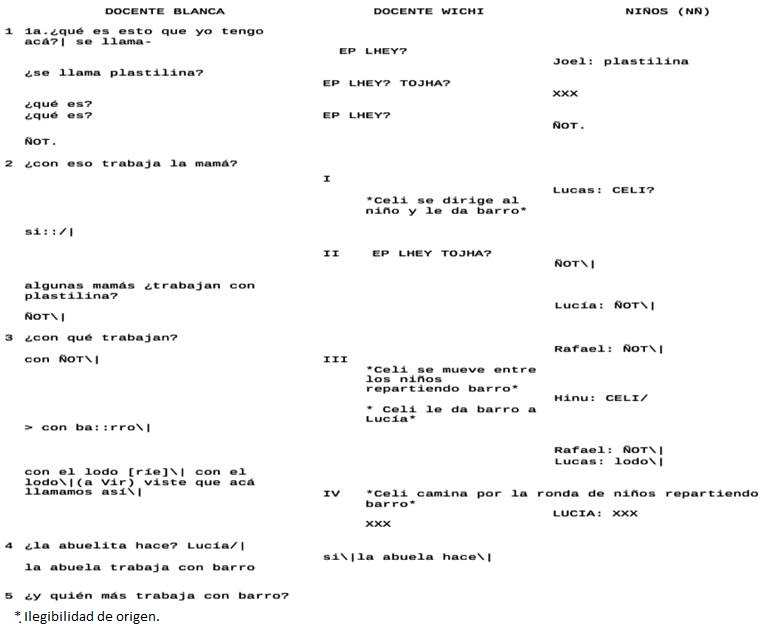

In this project, the teachers planned a first class in which the children had to compare the work they did in the kindergarten with play dough (“plastilina” in Spanish) with the work the women did in clay. The non-Wichi teacher pulled a piece of clay out of a box, showed the children the material and asked them if they knew its name. The Wichi teacher mediated continuously in the conversation. Not only did she translate, but also anticipated possible misunderstandings. One of the children proposed “Plastilina!”. The non-indigenous teacher asked again for an alternative answer. The children sought the answer in their own linguistic repertoire. They seemed not to know the Spanish Word for clay (“barro”) and proposed (i)ñot, the Wichi word for clay. The teacher insisted several times in search of the Word in Spanish, and finally accepted the answer in Wichi.

In Sequence 2, the teacher asked the children about their mothers’ jobs. The children took some time to answer, and the teacher insisted. She reformulated her question and they kept on saying ñot, not understanding what they were being asked. Finally, in Sequence 3, after reformulating the question again, she took the answer in Wichi (ñot) and reformulated it in Spanish (“con barro”: with clay), lengthening the vowels. One of the children said ñot again, followed immediately by another who said “lodo” (mud). The teacher accepted the answer, but turning to the researcher explained that it was a local variant of the Spanish word “barro”.

While this was taking place, Lucas, Hin’u and Lucía called to Celis, the Wichi teacher, who walked continuously among the little chairs the children were sitting on. Not only did they ask her for a piece of clay but spoke to her, one by one, to compare their ideas about what was happening and what they were expected to say (and do).

Lucía said something to the teacher which I could not understand. Celis walked towards her. From that closer position, she mediated between the child and the white teacher, inserting in the conversation what the Wichi child had told her from the lateral mode of it. Lucía had obtained Celis’s attention and, with her support, had been able to contribute to the interaction of the class.

Mario’s class

In the second case, I will discuss the notes of my visit to the Second Grade B group, where a non- Wichi teacher (Raúl) and a bilingual assistant teacher (Mario) collaborate.

I observed their classes for a week to compare the use of Wichi and Spanish in this kind of contexts that I call bi-managed. Although my observation focused on the use of the two languages in the classes, here I will discuss my notes on the way they are used by the children. My analysis of their performance could be seen as a window into the meaning of what happens and is done in these classrooms.

Vignette 1

The classes are organized by subjects (Mathematics, Spanish, and Science). Today is Math class. Raúl is sitting at the teacher’s desk, on the left side of the classroom and by the chalkboard. The attendance list and a Second Grade Manual are on the desk, as well as his pencil box and eraser. Mario greets me and I sit at the back of the class with the children who are coming back from recess. He greets me in Wichi and I respond. He smiles. We have known each other for years because he is married to a Wichi colleague with whom I worked in another school. Mario stands at the back of the class, his back leaning on the wall. The children take their places at their desks and pull their notebooks out of them or out of their backpacks. When they are all seated, Raúl stands up from his desk and tells them to copy some calculations he will write on the board. The children take their pencils and copy them. Mario remains standing until a little girl turns around and looks at him. He walks to her without saying a word and tells her in Wichi to copy the calculations on the board, leaning towards her and assisting her to copy. “She’s new in this class”, he tells me when he walks by me. Raúl goes back to his desk. There is complete silence. While Raúl fills in the attendance list, Mario walks by the children’s desks as the children look at him. After Raúl tells them that the time to solve the task is over, he asks the children for their results. None of them responds verbally. However, Mario walks towards one of the girls who have already finished, and touching her shoulder tells her to walk to the front of the class. She answers the first calculation on the board. The other children whisper to each other and to Mario in Wichi.

I would like to call some attention here to the formats of participation proposed by these Wichi second-graders, or those in which they participate. Through their movements, their gaze, or a seemingly subtle gesture, they contrast their ideas about what is taking place with the adult in the class who speaks their language. The children choose Mario as their addressee, and it is to him that they turn their eyes in the class dictated by the other teacher.

For his part, Mario moves around the classroom in a different direction from that of his non- Wichi colleague. Through their movements and the direction of their gaze and gestures, both the children and the teacher are able to reconfigure the scenes I observe. The non-indigenous teacher, sitting at the center of the scene constructed by the desks, is blurred from the viewpoint of what takes place among the children’s desks in the classroom.

As Goffman (2001) has pointed out, participating requires subtle but complex coordination among participants, who actively negotiate participation frameworks that change constantly. Participating in a social interaction requires correlating different semiotic modalities. The gaze and the position of the body, the gesture and the posture participate in the creation of interactional meaning (Mondada, 2011).

In the case I analyze, these multimodal elements coordinate in a peculiar way to establish formats or participation that run parallel to what happens at the main stage, and provide clues to approach the ways in which children give meaning to what is happening. The semiotic production of other modes of participation becomes evident mainly when faced with problematic situations, for instance when they have a question about the homework or they want to share the progress in their individual projects. The children deploy multiple resources that manage to define the situation and give some meaning to the activity in which they participate.

At Alejandra’s class

Vignette 2

The class begins in Spanish and Alejandra offers to tell them a story. She tells it little by little, using brightly colored pictures. The children look at her in bewilderment. My camera tries to capture the moment and zooms in on a group of children, until it stop son a girl who is about to cry. The girl looks at Alejandra and says to her “vos no” (“not you”). She is about to cry. Alejandra looks at me, as if she were asking for my approval to switch languages. The girl asks her to tell the story in Wichi. Alejandra explains to her in Wichi that it is only for a while, that she can speak Wichi if she wants. The girl is still uncomfortable, and finally Alejandra decides to tell the story in her language.

There is something I remember about this class and that I find difficult to explain. That “vos no”, complains about something that goes beyond some correspondence between language and speaker. It goes beyond a complaint to the teacher about the language she is using in class. It goes way back to the times when teachers have told stories in Spanish as though the children could understand them, as though their silences, their lost stares, were signs of something that “is happening”. As if it were not evident that most Wichi children - like the ones I observe in Alejandra’s class - cannot understand what they would love to understand.

In this class of Spanish as a second language, Alejandra, a Wichi teacher, had decided to tell the story in Spanish. Nevertheless, she switched languages and continued the story in Wichi. The girl smiled. After the class, some children approached the teacher and asked her for a copy of the story. In a corner of the classroom, three girls told the story to each other.

Luis’s class

Storybooks are an object of wonder for the children of the elementary school in the town of Los Lotes, where Luis and I work: their illustrations, their shapes, the shapes of the letters. One morning I went to a class in which Luis told a story about a cow that wanted to be white. First he read the story, as the children enjoyed the pictures in the book.1 Then he told the story again in Wichi and the children couldn´t stop laughing. They were fascinated with the story, and they all wanted to take the book home to tell it to their families.

The book tells the story of a cow who did not like her spots of color and wanted to be like any other “spotless” animal. After telling the children the story, Luis asked them what was happening to the cow. Matías spoke aloud and said in Wichi: “She doesn’t want to be herself. She wants to be another animal”. Luis went on: “Does this happen to you?” Matías replied: “Sometimes I’d like to be a criollo (an Argentinian of European descent)”.

Luciano’s class

Vignette 3

When I arrived to the class in the little school of Tres Pozos there were two teachers in the classroom: Luciano, a Wichi teacher, and Pedro, a non-indigenous teacher. Luciano was sitting, as usual in these classes, next to the children at the back of the classroom. Pedro was sitting at the front, next to the chalkboard. I placed my camera at the front of the class, as we had agreed.

Pedro began the class by introducing me to the children and explaining to them that I am Luciano’s teacher. Then, with a subtle but authoritative gesture, he signaled to Luciano to hand out some photocopies he pulled out of a folder. As Luciano walked towards Pedro’s desk, a little girl asked me my name. Then she told me in Wichi that she was afraid. “Of what?” I asked her. She looked at Pedro. “I am afraid of him too”, I said. “Scream” she told me.

These notes refer to another aspect of the participation of the Wichi children that is seldom considered, but that is noteworthy: the way in which they interpret the volume of the voice of white teachers and the meanings they attach to it.

Broadly speaking, the perception we have as non-Wichis is that they speak “in a low voice”. I remember a class of Wichi language I took. The class was full and I sat at the back to take notes. I felt as if I were deaf, because I could hardly hear what the teacher said but I noticed that all the other students took notes, asked questions and made comments about what was being discussed. At the end of the class, I asked my classmates if they had noticed that the teacher spoke in a low voice. They laughed and said that he did not, that I had the “white people deafness”.

The volume of the voice is another semiotic feature that is often overlooked when discussing participation. In the cases I analyze, however, it is fundamental. It is a feature that is categorized with regard to the meaning of the interactions; specifically, the meanings that the children give to their interaction in the classrooms with white adults.

For Wichi adults, speaking with children requires special care because they think that children “have a sensitive ear”. A low voice, whispering, and choosing “soft” words is considered part of the upbringing that constitute positive environments for their children.

In contrast, we white people shout and, in their view, always seem to be angry. In general, they do not quite understand why. Nevertheless, shouting and anger are part of their corporal and sensitive experience in the classrooms, experiences that are very far from friendly ones that invite them to participate.

Macarena’s class

Macarena is a non-Wichi teacher who works in a place near El Sauzalito. This fragment of my observations of her class helps me to consider other aspects of the children’s view on what happens in the classrooms where they study.

As I mentioned, most non-indigenous teachers do not speak the children’s language. However, this lack of knowledge is not described in the interactions as a problem, as if it did not exist. The interactions at school in which non-indigenous teachers are alone (without bilingual assistants), take place in such a way that there is no trace that they happened in exo-lingual contexts. Rather, they point to a fiction that is locally produced but socially sustained: that Wichi children understand and speak Spanish. Their silence is described and acted upon as a “cultural option”.

However, it may be relevant to point out here the tension between silence and communicative hegemony, or rather silence as a resource and being silent as a product. In classrooms with Wichi children this difference is fundamental both from a theoretical and a methodological viewpoint. From a theoretical viewpoint, it invites us to examine the opposition between the verbal and the non-verbal, and from a methodological viewpoint it involves considering the multimodal as data.

The notion of communicative hegemony employed here is part of the work on the ethnography of speech and points to something that is not restricted to linguistic ideology but goes far beyond it: hegemony is linked to naturalization and ideological saturation. In the case discussed here, it is related to what is seemingly unheard, unseen, unrecorded: the children’s voice - and the language in which it materializes - becomes invisible, inaudible (Unamuno, 2019).

This is linked to the ways in which school classes are structured: the use of multiple resources oriented towards minimizing the children’s participation in them, such as the prominence of closed questions that elicit mostly non-verbal responses, incomplete utterances that project their syntactic structure on very formatted responses, monological homework, and so on.

I will now show a fragment of Macarena’s class, from Los Lotes.

Vignette 4

Maca is a criolla. She has been working as a “common” teacher in this zone for almost 20 years and she has known the Wichi since her childhood. In my first visit to her class, Maca entered the classroom with me. She seemed to be angry. The children were still sitting down at their desks and looked at Maca with fear. Maca, in a loud voice and in an authoritative tone, said: “Let’s see… Are we people or ututus (lizzards)?” “People!” responded the children in unison. “Then don’t move your head like ututus. Look ahead. Be well seated, with straight shoulders. We are people. Peo-ple”. Maca turned around to write today’s date on the board. Nicolás, a Wichi boy I have known since he was a little child, laughs and with his right hand on his temple he makes the gesture of “crazy”, referring to his teacher.

This gesture made by Nicolás is particularly interesting for me, because somehow it made me reread the notes I took in these classes. In these notes, I observed especially the children’s lack of participation, the way in which Macarena pretended that her classes were “normal” while the children were absentminded or physically absent: they left the class through the door or the window and did not come back. Little by little, there were fewer and fewer children in the classroom, but Maca continued explaining calculations or asking them to complete multiple photocopies and then glue them to their notebooks.

The ideas around not seeing, not paying attention, not listening, not saying, appear as gestures linked to non-participation, formats of participation that produce absences. Nicolás, however, provides me with another clue. Through his gesture, he shows me that there is something anomalous in all this, and that they know it. This leads me to consider another approach to what is happening: the children can learn - and they do - to interact in these classes through their non-participation, although this does not mean that what is happening seems “normal” to them.

By way of conclusion

In this research work I have attempted to approach the children’s perspective through an analysis of participation. My methodological hypothesis is that studying it may provide clues on the ways in which give meaning to what happens in the classrooms where they study.

Through different classrooms and scenes, I have tried to construct an eclectic account that in broad strokes may make sense of a jigsaw puzzle. As I have pointed out, my interest in participation is based on the fact that I believe it lies at the foundations of the process of construction of knowledge. Thus, I consider four aspects of participation from the children’s point of view:

How they deploy their semiotic resources to solve the activities given to them by the teachers.

How they relocate and redefine the frameworks of participation in which they are involved.

How they categorize the situations of which they are part, including the types of bilingualism displayed in them.

How they interpret the semiotic resources available in the classrooms, including the volume of the voice and body control.

These aspects are presented here to discuss the description made of the children as “quiet and shy”, as well as to make sense of the ways in which, from non-Wichi perspectives, their participation in the classrooms is evaluated. Likewise, their analysis seeks - without any certainty of achieving it - to give a voice to the children and their views on crucial processes in which they are involved: their schooling.

It is common in Los Lotes that the children’s mothers are present in the kindergarten classrooms. They sit in a corner, watching what is happening. Every now and then, the children look at them and their mothers look back, accompanying them through these moments. For them, leaving their children at school is a complex process that involves trusting the adults in the schools. Wichi teachers are a key element in this trust for the children, for their mothers, and for me. They make all this arbitrariness-ridden process feel a little less strange, a little less crazy.

REFERENCES

Ballena, C., L. Romero y V. Unamuno (2015). Formación docente y educación plurilingüe en el Chaco: informe de investigación. Segunda parte. (Informe inédito), 2016. [ Links ]

Briggs, Charles L. (2005). Perspectivas críticas de salud y hegemonía comunicativa: aperturas progresistas, enlaces letales. Revista de Antropología Social, 14. [ Links ]

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis. The Critical Study of Language. Londres: Longman. [ Links ]

Goodwin, Ch. (2000). Action and embodiment within situated human interaction”. Journal of Pragmatics, 32, 1489-1562. [ Links ]

__________ y M.H. Goodwin (2004). Participation. En A. Duranti (ed.). A companion to linguistic anthropology. Oxford: Blackwell, 222-244. [ Links ]

Gumperz, John J. (1982). Discourse Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Mondada, L. (2011). Understanding as an embodied, situated and sequential achievement in interaction. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(2), 542-552. [ Links ]

Quiros, J. (2014): Etnografiar mundos vívidos. Desafíos de trabajo de campo, escritura y enseñanza en antropología. En proceso de publicación. [ Links ]

Unamuno, V. (2013). Gestión del multilingüismo y docencia indígena para una educación intercultural bilingüe en Argentina. Praxis Educativa, 7, 31-54. [ Links ]

__________ y L. Nussbaum (2017): Participation and language learning in bilingual classrooms in Chaco (Argentina) / Participación y aprendizaje de lenguas en las aulas bilingües del Chaco (Argentina). Infancia y Aprendizaje/ Journal for the Study of Education and Development. DOI: 10.1080/02103702.2016.1263452 [ Links ]

Unamuno, V. (2019). Sobre ‘lo silencioso’ y ‘lo bilingüe’ en las aulas con niños wichi en la Provincia de Chaco. En V. Zavala, S. de los Heros y M. Nino-Murcia (eds.). Hacia una sociolingüística crítica: desarrollos y debates, Lima, en prensa. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, E.M. (2009). Educación Superior Indígena en el Centro de Investigación y Formación para la Modalidad Aborigen (CIFMA): génesis, desarrollo y continuidad. En D. Mato (ed.). Instituciones Interculturales de Educación Superior en América Latina. Procesos de construcción, logros, innovaciones y desafíos. Caracas: Instituto Internacional de la UNESCO para la Educación Superior en América Latina y el Caribe, 79-102. [ Links ]

Valetto, R., V. Unamuno, F. Valetto y C. Fernández (2018). Representaciones respecto de las prácticas docentes en contextos de Educación Bilingüe Intercultural. En: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, Ciencia y Tecnología, Investigación en los Institutos Docentes. Inclusión, trayectorias y diversidad cultural. Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Educación, Cultura, Ciencia y Tecnología. [ Links ]

Received: May 29, 2019; Accepted: September 27, 2019

texto en

texto en