Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Diálogos sobre educación. Temas actuales en investigación educativa

versão On-line ISSN 2007-2171

Diálogos sobre educ. Temas actuales en investig. educ. vol.10 no.18 Zapopan Jan./Jun. 2019

Thematic axis

Two rural teachers in Durango, Mexico. From the Cristiada to Henriquismo1

* Ph. D. in History, Mexico’s National Autonomous University. Center for Culture and Communication Studies. Universidad Veracruzana. Xalapa, Veracruz, Mexico. Lines of research: the press in Mexico’s regions, cultural history. celiadelp@yahoo.com.mx

In this paper I will explain my parents’ participation in a convulsive period of Mexican history. My father was a rural teacher in the state of Durango and my mother, although not trained as a teacher, also worked as one in different places within the state. During their years as teachers they worked under threat because they had to follow the State education policy of socialist education. They were persecuted and more than once they had to leave the villages in the middle of the night. Years later my father joined the Henriquez movement, which would ultimately be defeated, and had to leave Durango for Mexico City. Based on the family documents left by my father (personal accounts, some letters and official documents, photographs), I intend to describe the vicissitudes of a couple who obeyed orders in their teaching work and later fought against the establishment through partisan politics, being defeated in the end.

Keywords: Rural teachers; socialist education; State of Durango

En este trabajo explicaré la participación de mis padres en un periodo convulso de la historia de México. Mi padre fue maestro rural en Durango y mi madre, sin ser maestra, también realizó estas labores en distintos lugares del estado. Durante sus años de maestros se vieron amenazados, ya que tenían que cumplir con la política educativa estatal impartiendo la educación socialista. Fueron perseguidos y más de una vez tuvieron que abandonar los pueblos en medio de la noche. Mi padre se afilió luego al movimiento henriquista, que a la postre sería derrotado, y tuvo que salir de Durango hacia la Ciudad de México. En este trabajo, basado en los documentos familiares que dejó mi padre (recuentos personales, algunas cartas y documentos oficiales, fotografías), pretendo dar a conocer las vicisitudes de una pareja que obedeció órdenes en su labor docente y posteriormente luchó contra el poder establecido desde la política partidista, viéndose al final derrotada.

Palabras clave: Maestros rurales; educación socialista; estado de Durango

Here it is then, the full story of what is and will continue to be, for as

long as we and our children and our children’s children remain alive.

María Elena del Palacio Montiel2

Introduction

I agree with the editors of this issue of Diálogos sobre Educación that social biography allows us to learn about the life of a collectivity and even of an era through personal experiences. That is precisely my aim in this text: to show, through the personal experiences of my parents in their native Durango in the 1930s and 1940s, and how the everyday life of rural teachers was. Their experiences give us a glimpse of the social and political life in the state of Durango at that time. Through my parents’ stories we can learn about the everyday life of schools in small towns in the state, and how they dealt with the educational policies of that time and adapted them to their day-to-day practice, their very real shortages of material, which led them to even build some of those schools. I will show how coped with the attacks of religious and ethnical groups in the region that tried to stop them from implementing a socialist education. 3 These experiences also show the gap between what the national policy aimed for and what could actually be done on the ground in the regions of Mexico.

The tools to build a narrative

The materials

The box is in my studio now. For many years it was in the custody of my brother Jaime, who intended to write this story (or may have done it: he claims to have written dozens of pages that he cannot find now, part of which went into his novel Parejas). Other documents, especially photographs, were kept by my sister María Elena, who inherited them from my mother. I remember those childhood photos. They were pasted on an album with wooden covers and black paperboard pages, held in place by paper corner framings. Over the years, my sister took them out of the album, “classified” them according to which of my siblings was featured more prominently in them, and gave them to each one of us. There were, however, many - dozens of them - in which none of us appeared.

Recently, when I began to write a text to be presented at the CIESAS-INAH-UBC Permanent Seminar on Citizen Memory: Retrieving Everyday Life Through Family and Personal Sources (“Memoria ciudadana, recuperación de la vida cotidiana a partir de fuentes familiares y personales”), I asked my sister for those photographs. She gave me a huge bag with all the photographs mixed together. In her defense, I must say that she spent years noting in the back of each photograph where and approximately when it had been taken as well as who appeared in it, in her beautiful handwriting. And there are not only images: the small archive also includes letters and other official documents, personal letters, newspaper cutouts and an autobiography written by my father, all of it thoroughly classified by dates. Those are my sources.

When I wrote this paper I had to deal with mixed emotions: first, the excitement of realizing that part of my history, which I know by heart and nurtured my childhood, may be of some value for others. Yet at the same time I felt a kind of shyness about revealing events that, although part of a public history, are also part of my family’s history.

I also had to deal with the fact that I am not a specialist in the regional history of Durango in the early decades of the twentieth century. There was a lot of research to be done in order to be able to insert a personal history into the history of the region and the country. This is one of my first attempts, although I know there is still much to be discovered.

For this first approach, I have taken as a reference some guidelines from self-ethnography, a “genre of autobiographic writing and research that links the personal with the cultural” (Ellis, 2003: 209) and that has been used to approach family history. This involves a first-person narrative that accepts “the complications of what you find yourself studying” (Blanco, 2012: 55).

On the one hand, this approach has at its core the idea that “a society can be read through a biography” (Iniesta y Feixa, 2006: 11) and does this “through the mediation of its immediate social context and the limited groups to which it belongs” (Ferrarotti, 1988, in Blanco, 2012: 55). That is an important premise for this paper because, in dealing with a personal biography, I believe it can help to understand the society in which the person lived - in this case, the society of rural Durango in the first decades of the twentieth century.

On the other hand, it is also necessary to discuss briefly here the concepts of autobiography, history, and memory. Autobiography is seen as an account of purportedly real events in which the chronicler may include opinions and feelings; that is, his or her own subjectivity. Thus, the facts being narrated are “decanted, assimilated, established in the author’s memory” (Guijosa, 2010: 41).

Jacques Legoff asserts that “memory is the raw material of history” (1988: 1,071), and Elizabeth Jelin speaks of the ways in which both memory and history are in turn related to autobiography. She also speaks of memory as a resource for research in the process of obtaining and constructing “data on the past […] the role that historic research may have in ‘correcting’ false or mistaken memories […] and memory as a subject of study or research” (Jelin, 2002: 63). This is what I will have to deal with as I analyze my parents’ autobiography and the actual memories of what they told me.

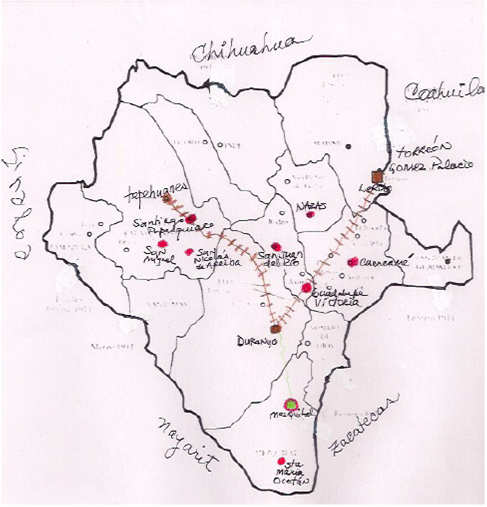

It is necessary to “locate historically the characters, the shaping of the political stage of which they were part, the struggles for meaning in which they were immersed …” (Jelin, 2002: 70). To do this, a minimal bibliography has accompanied my inquiries: Victoria Lerner’s book on socialist education (1982), Elisa Servín’s work on henriquismo: Ruptura y oposición. El movimiento henriquista, 1945-1954 (2001), Antonio Avitia Hernández’s work in several volumes Historia gráfica de Durango, Los alacranes alzados, historia de la revolución en Durango, as well as a more specific one by the same author, El caudillo sagrado: historia de las rebeliones cristeras en el estado de Durango, and several scholarly works on socialist education and rural teachers’ colleges.

Carolyn Steedman (1993) argues that an author masks history itself when he or she writes an autobiography. Since that is not my intention, to give an idea of my own position in this history I will say that I am the youngest of six siblings, the last one to be born, in 1960, in a family that began in 1935, when my parents got married. I was born in Mexico City, after my family’s exodus following the defeat of henriquismo in the state of Durango. Far behind was the history that surrounded my parents’ and my siblings’ lives. I knew nothing of the traveling life that they led, full of deprivation and danger, in the rural areas of that state in the north of Mexico.

For this approach, I have decided to base myself on the autobiographical writings of my father, which he had bound in the last years of his life and that comprises 56 pages typed in 1.5 spacing on bond paper. It is entitled “Biographical and anecdotal data of Juan Francisco del Palacio Zavala, 1912-1982” (“Datos biográficos y anecdóticos de Juan Francisco del Palacio Zavala, 1912-1982”) (a curious marking of a period, from the year of his birth to the year when he turned 70). These data must be read with caution since in some passages there are discrepancies with the accounts my father himself made to me, and dates that do not match others. This is what Jelin (2002) refers to when she speaks of false or mistaken memories. However, there are also a great deal of verifiable data supported by official documents, newspaper cutouts and facts recorded in the bibliography I consulted. What is important at any rate is the narrative, how my father tells the events in which his life was part of that history. That is, for the effects of this paper, what matters is how his personal biography personal can be incorporated to the social biography of his time, of the place where he lived and worked as a rural teacher.

The life story

My father was born in 1912 and, according to his autobiographical account, as a Young child he saw Francisco Villa’s troops enter the city of Durango. He describes the episode:

When Villa took the city, it was defended by Carranza’s troops; I do not remember under what general’s command they were, but they were defeated by the Villistas. They were scattered and some of them left town through Tierra Blanca [the neighborhood where he lived with his family], in the south of the town. They were completely disorganized, some on horseback but most of them on foot, the latter dumping their rifles and taking off their vests […] (Del Palacio, 1982, f. 2).

He also says that his uncle from his mother’s side José Aldama, was a first captain in the Villista army, while his father Juan del Palacio was a major in Carranza’s, although he points out that there was “never any kind of controversy” between them, despite the fact that they fought on opposite sides.

Once the dictator Huerta was overthrown in 1915, constitutionalist troops under generals Mariano and Domingo Arrieta fought the Villista army led by Tomás Urbina. During the following years there was a tug of war between both sides, which took and then lost the capital city of Durango. It is hard to tell which of these Villista occupations my father speaks of, since due to the age he was then it could not have been in 1915 but only after 1917-18.

In the following pages he describes his first years in elementary school and his illness: he caught the Spanish flu, a serious epidemic that claimed millions of lives around the world and also decimated Durango in 1918, forcing the city to close schools and public venues (Avitia, 2013, t. III: 180). My father also adds to his story folk tales and legends of ghosts and apparitions4 that people in Durango are so fond of, and describes the grim presence of garbage trucks that, during the uncontrollable epidemic, carried piled up dead bodies to the cemetery.

After finishing “primaria superior”, as completing six years of elementary school was then called (Lerner, 1982), my father went to Escuela Central Agrícola de Santa Lucía, a rural teachers’ college near Canatlán and 40 kilometers north of the city of Durango founded in 1926 to train rural teachers (Avitia, 2013, t. III). He says that students from other parts of the country also went to that school and that in the years he spent there he learned to do farm work. After that he went to Escuela Normal Rural de Galeana, another teachers’ college in the state of Nuevo León where at the age of 17 he practiced teaching with groups of students aged 15 or 16. While Escuela Central Agrícola de Santa Lucía no longer exists, the Escuela Normal Rural de Galeana was more prestigious at the time.

The Escuelas Normales Rurales (rural teachers’ colleges) were created after the Revolution of 1910 as part of an ambitious cultural project that sought to transform the life of rural communities through schooling. Their initial objective was to train teachers who could educate peasants in rural schools that would open throughout the country (Civera Cerecedo, 2015).

On the other hand, the “Centrales Agrícolas” appeared during the government of President Calles “as a project that, with modern machinery and a cooperativist organization, would improve Mexico’s agricultural production” (Padilla, 2009: 85). Both kinds of educational institutions merged in the early 1930s under the name “Escuelas Regionales Campesinas” (“Regional Peasant Schools”) with a much more ambitious project:

[…] undertake a transformation of the countryside by integrating cultural, sports, educational, economic and political organization activities within the framework of agrarian reform and the shaping of the post-Revolution State. Young people between the ages of 12 and 17 años were educated under a curricula of four years following three or four years of elementary school, which combined the training of rural teachers with that of agricultural technicians to train leaders who were independent, responsible and autonomous, knowledgeable in agricultural and animal husbandry techniques, rural crafts and civic culture, the articles in the Mexican Constitution that protected peasants and laborers, young people who knew what was needed in the countryside and could use techniques to help promote the sharing of land, create cooperative production associations, open schools, promote hygiene and sports, organize the celebration of national festivities and other activities such as literacy campaigns (Civera Cerecedo, 2015: s/p).

Civera mentions that the young students there were the children of communal farmers (“ejidatarios”) or small landowners. They received a scholarship from the federal government, room and board expenses, and upon finishing their studies they would obtain positions as rural teachers (Civera Cerecedo, 2015).

My father does not delve into the reasons why he had access to such an education. Although his family was not well-off, he was an urban youth from the capital of the state of Durango. How did he manage to occupy a place in those schools? Perhaps someone’s recommendation made it possible. It must have been urgent to find him a space because the family could not afford to support all their children and being admitted in that school virtually ensured him a good future. Even though my grandfather Juan del Palacio came from a family with a long history in Durango, he was disowned when he married my grandmother Refugio Zavala, a girl from a poor background, and also because he renounced the Catholic church to become a spiritist and agnostic.

Nor does my father’s historic and anecdotal account give any details about his activities in the teachers’ colleges where he studied. He only speaks of the mischief he was involved in, teasing fellow students, and how he refused to perform the hardest tasks of working in the fields, preferring instead to prepare and serve food in the kitchen, which was also the responsibility of the boarders.

Students took turns to attend to all the needs of each school, its farming annexes and workshops, food and cleaning, giving a great value to work, discipline, the vocation to serve and their commitment to the community (Civera, 2015).

The years between 1929 and 1932 are in the air in my father’s historical account. He says that he went back to the city of Durango and, apparently, had no intention to work as a teacher. He looked for jobs in the city and had fun with his friends. The typical outing then was the afternoon parties at the Terpsicore club in El Pueblito - a sort of suburb that is now part of the metropolitan area of Durango - that is still today a place for social gathering, famous for its restaurants and bars. In 1929, however, youths had to go there along an open road and risk the violence created by political instability. One day, on their way back from El Pueblito, the “gang”, as he calls it, encountered a group of four soldiers who made them get out of their car. The sergeant accused them, in very rude language, of carrying munitions to the cristeros that ravaged the region and was about to have them shot, and they were only saved by the lucky arrival of a captain who cleared up the confusion. “After that Sunday, nobody wanted to go to El Pueblito”, he says.

Indeed, in March 1929, Durango was the only state capital controlled by the cristeros allied to the Escobarista uprising. 5 The agraristas led by José Guadalupe Rodríguez, a communist teacher who prepared a Mexican soviet revolution in Durango, were armed to fight the cristeros and forced them to flee the city one month later (Avitia, 2013, Vol. III).

The adventure of teaching

In 1932, probably tired of the badlypaid jobs he had had until then, my father attended a political meeting held by the then Minister of Education Narciso Bassols, with whom he spoke to claim his position as a former student of a rural teachers’ college. Bassols must have put in a good word for him with the Director of Federal Education in Durango, because in January 1933 he was sent to a school in San Diego de Alcalá, near the Poanas railway station - not far from the city of Durango - as the school director.

The official correspondence in my father’s personal archive shows the paperwork that had to be done. The representative of the Federal Directorate of Education wrote letters to the current school director and the Military Chief. Since teachers were a central figure in any town, the Military Chief of the area had to be informed of the appointment. His salary as a school director would be forty pesos a month. He could not have asked for more. However, when he arrived to the school, the current director refused to hand her position over to him and went immediately to Durango to complain to the representative of the Federal Directorate of Education, who reversed his previous decision.

My father had to go back to Durango, and shortly afterwards he was commissioned as assistant to the school director in a place known as Chinacates. When he asked a public official where that town was, he was told to look it up in a map. It was somewhere near Santiago Papasquiaro, the capital of the municipality. So he took the train to Tepehuanes, to take his new assignment in a place that seemed to him “horrible, without even a small tree and with so much dust in the air that houses were not visible even at short distances”. The school was not much better:

[…] my introduction [to the director] took place in the schoolyard, which was 50 meters long by 25 meters wide, at the end of which there were some latrines built with a few wooden planks that seemed about to collapse. The building that housed the school had been a warehouse that had been divided in two sections, of which the larger one was used for the first grade and the smaller one for all the others. Furniture was almost non-existent: a few old benches, boards and stones, in a school with no windows, only a few holes in the walls without boards to shut them […] (Del Palacio, 1982: f.16).

My father had chosen to teach the first grade. He was shocked when he learned the group included 116 children, 70 boys and 46 girls, with a very uneven level of education.

He also had to build a pigeon loft to keep the birds from filling the classroom with their droppings, as well as a rustic library with a few wooden boxes. When the director was fired, he took over all the grades and had to ask a family in town with whom he had become friends to help him keep order in the school. Such were the needs of places like that in the 1930s.

Things were not much better in the rest of the country. Lerner writes that there were “an insufficient number of teachers for the number of children of school age” (Lerner, 1982: p. 107); in 1930, Lerner found there were 32,657 teachers, of the 90,000 required to teach 3.5 million children at the age to start elementary school. Lerner also mentions the teachers’ low salaries, the delay in their payments, and how they were forced to change jobs in order to make ends meet.

The dire conditions of the school, the responsibilities he had as the only teacher and director, and the difficulties mentioned by Lerner, drove my father to go to Durango and apply for a different assignment, which he obtained at the end of the school year.

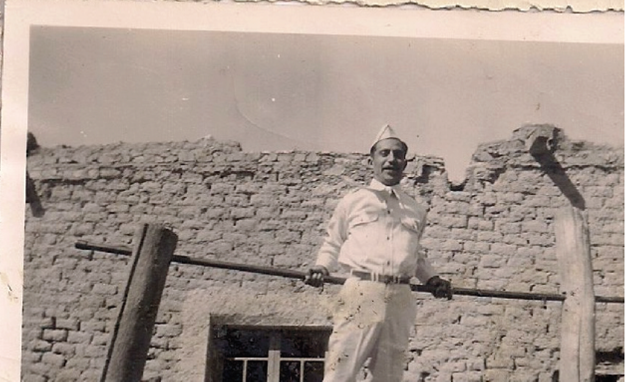

Photograph 1 Part of the building that housed the school in Chinacates, Durango, 1933. Del Palacio Family Archive.

In August 1933 he was commissioned as the director of the school in San Miguel de Papasquiaro, a town located 40 kilometers away from Santiago, the capital of the municipality. There he took lodgings in the house of Celestino Montiel, whose daughter - my mother - he would marry two years later, and whose elder daughter Laura was already a teacher and became my father’s assistant at the school.

The situation changed radically the following year. My father does not mention it in his memoirs, perhaps because he forgot about it, but taking into account the stories my mother told me about that time, her family retreated to the capital of the municipality, perhaps because of the redistribution of the land that began to take place in the region, perhaps because - as she claims - they were dispossessed of their land, or due to the violence that again began between the agraristas and the guardias blancas in the mountains and that began to affect the smaller towns. Land redistribution had begun in Durango in 1929, albeit in a smaller scale, and it was not until 1935-1936 when it was expanded as part of President Lázaro Cárdenas’s policies (Avitia, 2006; 2013).

My grandfather Celestino had already been kidnapped eight years before by a gang of cristeros under the orders of Juan B. Galindo, a former Villista bandit who operated in 1926 from the area of Indé, Tepehuanes, and Santiago Papasquiaro, to Chinacates, and who could never be apprehended by federal forces (Avitia, 2006). The fact that my grandfather was held in the mountains for several weeks and was miraculously saved must have been very traumatic, so new outbursts of insecurity may have influenced the family’s decision to leave everything behind and move to Santiago. Laura was changed to the school in Presidios, and my father recounts that he also asked for a change in his job, but since there were no positions available in schools nearby he agreed to go to a boarding school for indigenous students in Santa María de Ocotán.

Santa María de Ocotán is located south of the city of Durango, near the state border of Durango with Nayarit and Zacatecas. The boarding school was created in 1930 with the aim of teaching literacy to inhabitants of areas occupied by cristeros in order to eradicate the ignorance and fanaticism that were believed to have been the causes of the Cristero uprising (Avitia, 2006). Such boarding schools were part of the educational policies of the time and would be a bastion of socialist education (Lerner, 1982).

Although distant, that place, situated in the Western Sierra Madre and according to my father only reachable from San Juan del Mezquital after four hours on horseback, was, unlike the other schools where he had worked, perfectly equipped: there were dormitories for boys and for girls, and even a swimming pool with showers and all services. Their main task was to teach Spanish to the Tepehuano children in the region. And it was there where my father had his first encounter with the groups known in the region as cristeros.

In Durango, these groups were somewhat different from cristeros in other parts of Mexico, especially those of the so called Segunda Cristiada, active from 1934 to 1941. They were comprised of rural population, mostly groups of “mestizo and Tepehuano, Huichol and Mexicanero indigenous peasants from the south of Durango” (Avitia, 2013, tomo IV: p. 54; Avitia, 2006). This is in itself worthy of attention because these groups were not even Catholic. More than religious, their motivation was more closely linked to ethnic and territorial resistance against the logging industry that was beginning to invade them (Avitia, 2013, Vol. IV: 54). The territorial conflict, especially in Santa María de Ocotán, made the town a very dangerous place. The land deeds granted to the Tepehuanos in the nineteenth century were not respected by the surveying companies and the rights to the land were given by the government to private loggers in 1933, which generated a conflict that continues today (Avitia, 2006).

For the mestizos and indigenous people of the Sierra, their motives were ethnical survival, true enforcement of Article 27 of the Constitution, preservation of communal wooded lands, limiting the advance of multinational logging companies, and settling of power disputes between leaders of indigenous groups in the Sierra and mestizo towns to control the fate of the Sierra. (Avitia, 2006: 153).

For these and other reasons I will list below, the Durango State Cristero Liberation Army (Ejército Liberador Cristero del Estado de Durango) was formed and began to operate mostly in the southern part of the state, although some groups were also created in the municipalities of Durango and Canatlán. All through president Cárdenas term these territories were the scene of this uprising, whose outcome is still difficult to fathom (Avitia, 2013, t. IV: 131). These cristero leaders, abandoned by urban Catholics and even by the hierarchy of the church, began to fall in 1936 and the region was finally pacified in 1941.

Besides territorial resistance in the south of Durango, this second Cristiada adopted as a motive for their struggle the national educational guidelines that ignored “the indigenous particularities of the region” (Avitia, 2013, t. IV: 54; Avitia, 2006), and that were part of the educational policies of the time: to teach Spanish, to proscribe indigenous languages, and to a certain extent to “deindianize” them (Lerner, 1982: 139). Precisely because of this westernizing educational policy, indigenous boarding schools nationwide did not have the support of mestizos nor of ethnic groups, since it left the children unable to adapt to their communities or to the urban environment (Avitia, 2006). The policy was somewhat tempered at the end of president Cárdenas’s term, under the pressure of national and foreign business leaders, as well as Mexican society at large (Vaughan, 2000). 6

To better understand the attacks against the Indigenous Boarding School in Santa María de Ocotán we must take into account a personal factor that was added to the others: the relationship that the former cristero chief Florencio Estrada had with the boarding school. After being granted an amnesty in 1929, Estrada was appointed food supplier for the school. Due to his alleged shady dealings, he lost the appointment and turned to guerrilla war against the government and the indigenous people who supported the government (Avitia, 2006). 7 The attack my father witnessed in early 1935 was led by cristero general Trinidad Mora, who reported it thus to his National Guard:

We are perfectly united. We already went to Santa Maria Ocotan and took out [sic] a boarding school for children and youths that the government had to lead them into perdition. We took out all they had in the school and I took the director’s son prisoner in order to demand a ransom, and it seems he is willing to pay it (Avitia, 2006: 309).

The military chief had already alerted the teachers of the possibility of an attack, as my father recounts, and he, along with other teachers, left the boarding school in the middle of the night, walked for two days to San Juan el Mezquital, and arrived to Durango on a freight truck, ready to hand in his resignation. The director’s son kidnapping became known all over Durango and teachers in the state organized themselves to raise the money for the ransom (Avitia, 2006).

Without a doubt, the enforcement of socialist education was an important factor leading to the end of a period of relative peace between the cristeros and the government from 1929 to 1934. However, as Medina (2018) points out, many of the regional and local conflicts attributed to socialist education were actually caused by older sources of tension between local actors, as can be seen in the case of Florencio Estrada’s cristero gang mentioned above.

In the case of Durango, the students of Instituto Juárez in the capital city of the state went on strike against the enforcement of the new educational policy (Avitia, 2006), and many other Catholic associations joined the protest.

Socialist educational policy was passed into law in December 1934. Its main tenets, inscribed in Article 3 of the Mexican Constitution, were:

The education provided by the State shall be socialist, to the exclusion of any religious doctrine, and shall fight fanaticism and prejudice, and to that end schools shall organize their teaching and activities in such a way that enables them to create in youth a rational and accurate concept of the universe and of life in society (Lerner, 1982: 82).

This education upheld secularism and the authority of the State over the school. Rural schools and the teaching of useful knowledge would be favored. It must be pointed out that there was a lack of clarity in the goals of this reform, and not even its name was very clear: “socialist”, “rational”, or “active” education were used indistinctly, etc. The arguments over what kind of socialism would be implemented were very intense (Palacios, 2011).

Frightened by his experience in Santa María de Ocotán and hoping to keep away from danger, my father decided to try his luck at the Durango State Directorate of Education. In September 1935 he was put in charge of the elementary school in Antonio Amaro, near Guadalupe Victoria. However, he was also harassed there by the cristeros who remained in the area and had to run away in the middle of the night to hide in the wilderness, after the townspeople alerted him of the arrival of the cristeros.

Although it is known that socialist education in other places in Mexico was opposed through nonviolent means such as absenteeism in schools, as Lerner notes, it was precisely in the state of Durango, where they blew up explosives in a school. Teachers and government agents who advocated the educational reform were violently rejected in the capital of the state. Other accounts describe mutilations (Lerner, 1982: 113) and even deaths in the states of Jalisco, Puebla, Guanajuato, and Michoacán (Palacios, 2011). In Durango it is known that rural teachers were murdered in the region of Canatlán (Avitia, 2006). My father heard of cases in which

[…] the teachers they found in the schools, if they were men, had the soles of their feet cut off and were forced, still bleeding, to walk among the rocks, and that if they were lucky, because otherwise they had their genitals cut off and were abandoned to their fate. Women fared no better: the ones they found, either in a school or in their homes, were taken out by force, raped, had their breasts mutilated and, once their attackers’ beastly instincts were satisfied, were abandoned naked in the mountains or the wilderness (Del Palacio, 1982, f. 21).

What motivated such attacks? Which activities conducted in the schools could have been so threatening for the clergy and the students’ parents? The causes of the cristero raids on the schools where my father was in the following years could have been, as Palacios writes:

Because teachers in that school refused to allow the use of religious texts, because they taught the children revolutionary songs, because they published the newspaper Alborada and posted the Parcela wall newspaper, because they held cultural festivals featuring dances and social dramas without any religious contents, because they implemented school breakfasts, because they strove to get school supplies and clothes for poorer children, because they accepted children under the age for elementary school and provided them shelter in beds that, in the imagination of the towns’ priests and some neighbors, were visualized as used to teach sexual education (AHEM/Fondo Educación/Serie Dirección de Educación/Toluca/1938/Vol. 391/File 20, in Palacios, 2011, s/p).

A similar cause was argued by people like Trinidad Mora, one of the last cristeros to surrender:

I am a Catholic citizen and as such I cannot allow organized tyranny to reduce me to a level worse than that of a slave, tearing down the churches in which I worship God or turning them into night clubs and houses of prostitution and persecuting the priests that for me are the representatives of the Great Maker. I am a man and a parent, and in that capacity I cannot abide to let anyone touch my home or my children, because other than God the only one who has the right to inculcate in them any ideas he pleases is me, and neither Calles nor Cardenas nor anyone else is in any way entitled to, as they say, “socialize” children (Avitia, 2006: 313).

My father recounts that this persecution of teachers had its origin in some confusion in terms: priests had told the cristeros that what was being implemented was “sexual education”, not “social education”. The priests had told the rebels that “[we] the teachers undressed the girls in class in front of the boys and told them how their sexual organs worked. Nothing could be more false.” (Del Palacio, 1982, f. 20).

Socialist education supported gender equality and co-education, named so because boys and girls received the same education, without allowing “sensual feelings to develop” (Lerner, 1982: 98). The very fact that schools were coed was seen as an offense to the Church and conservative sectors of the population (Medina, 2018). All of that of course scandalized many parents and members of the clergy, who totally opposed the implementation of this system. In fact, the phrase “sexual education” seems to have come from them, since it was never mentioned in the official documents consulted (Palacios, 2011).

Again, my father tried to stay away from danger, so he asked for an indefinite leave of absence, as many other teachers did at the time (Avitia, 2006). After several months and different jobs in Santiago Papasquiaro, and already married to my mother, he decided to go back to teaching at the Directorate of Federal Education. He was appointed principal of the school in San Nicolás de Arriba in the municipality of Santiago, a densely wooded area that they enjoyed enormously and where they appear to have been safe from the cristero raids that, although they continued in places like Canatlán, Cuencamé, or even the capital city of Durango, seem to have ceased in the municipality of Santiago Papasquiaro.

In the school of San Nicolás de Arriba my mother became an assistant in April 1936, with a salary of 40 pesos, and eventually as the school director upon my father’s resignation in October 1937. She would later resign from that position to join my father as his assistant in the Escuela Superior Guadalupe Victoria in El Mezquital, where he was working.

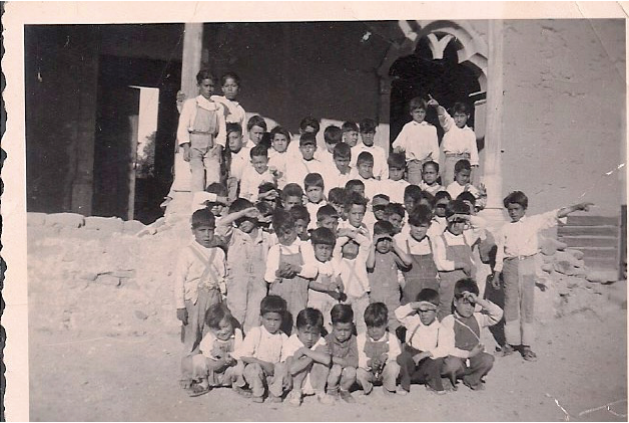

Photograph 2 Group of students in the school of San Nicolás de Arriba, Municipality of Santiago Papasquiaro, Durango, 1936. Archivo Familia Del Palacio.

My mother had only studied the so called “basic elementary school”. In San Miguel, where she was born, only the first three years were offered. Encouraged by my father, she managed to finish it and then become an assistant teacher, to help him in the schools where there were no other teachers. That was hardly unusual: according to Lerner, out of 32,000 teachers at the time, less than 10,000 had completed their elementary school studies and almost 3,000 had studied only basic elementary school (i.e., the first three years). Very few of them had, like my father, attended teachers’ college (Lerner, 1982: 108-109).

They stayed in El Mezquital, which my father describes as beautiful but full of scorpions, from 1938 to 1939. In spite of the scorpions its lush vegetation, orange orchards and weather earned it the nickname of “Little Cuernavaca”. Not far from it are a lake and a waterfall with rocky outcrops that resemble tiny houses. The town of Pigme still attracts tourists to Durango, and in my family archive there are photographs of my parents with their children, their students and their fellow teachers enjoying the countryside, which portray everyday life in the town and how its inhabitants escaped the boredom and tiredness of their daily routines.

Shortly afterwards, in January 1940, they took charge of the Benito Acosta public co-ed school in San Juan del Río. By then they had two children, and a third one would soon be born. They remained there until 1941. As my father tells in his autobiography and my mother in the stories that I can remember, they were always sent to schools that needed repairs. That was the case in San Juan del Río: “[…] the previous principal took with him the books … and one of the rent collector’s daughters” (Del Palacio, 1982, f. 35). Despoliation of schools was not uncommon, and the conditions of the buildings were often deplorable. After Mexico’s nationalization of its oil industry in 1938, the situation of rural schools became increasingly difficult. According to Civera Cerecedo, “Teachers, students and parents often contributed with their work and materials to build classrooms, workshops and annexes, with the help of nearby rural communities. It may be argued that they literally built their schools themselves.” (Civera, 2015, s/f).

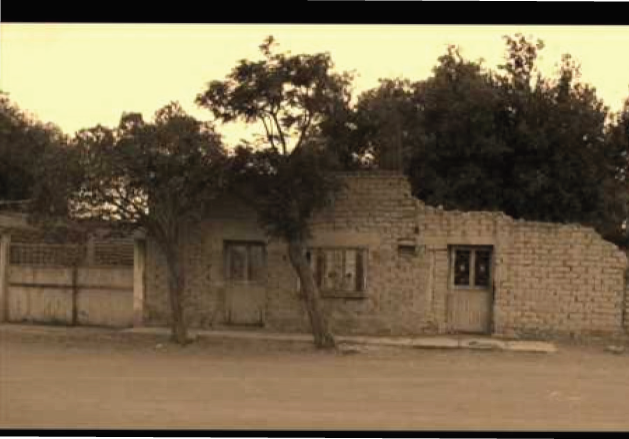

At the end of the school year, my parents were commissioned - he as a principal and she as an assistant - to Cuencamé, which at that time could be reached by railroad. The Second World War found them there and my father had to take military instruction and then see that it was given to everyone over the age of 16, men and women, even if they did not attend school. That was also his responsibility as a teacher at a time of great concern about the war. Teachers had to foster a patriotic spirit and organize parades and gymnastic exercises. The photographs in the family archive show the military exercises and parades outside schools built with mud bricks, in dusty and sun-drenched fields.

Photograph 4 Comitee for the Monument to the Flag, Cuencamé, Durango, 1941. Archivo Familia Del Palacio.

In July 1943 my father had been appointed principal and my mother again as his assistant in a co-ed school in Nazas, a town near Torreón which could also be reached by railroad. There, my father advocated for the construction of a secondary school and organized a cooperative association for production and sales with a store that, as he recounts, was quite successful. The students’ parents and municipal authorities even signed a letter preserved in the family archive asking the educational authorities to let my father stay there longer.

However, in 1944 my fatehr was offered the position of principal of the Agustín Castro school in Guadalupe Victoria, a much larger town whose inhabitants, my father said, had a murderous reputation. But the salary - 200 pesos a month - persuaded him to accept. Since Victoria was a bigger town, it had a “fully organized school” with 12 teachers who had studied at Durango Teacher’s College, quite a luxury at that time. In that school my mother also worked as an assistant, teaching evening classes for adults until 1946, and then as a group assistant from 1949 to 1950. In that town, my father enjoyed organizing activities:

[…] several teams, the sports club and the student committee […] girls from 18 to 20 years old formed a basketball team, the Adelitas, and won a few games. Among men from 22 to 25 years old I organized a basketball team, Los Panchos, since we all shared the name Francisco. This team also became incredibly famous after playing with teams from Torreón, Gómez Palacio, Fresnillo and Aguascalientes, making the town of Guadalupe Victoria renowned and mitigating the dark and murderous reputation gained by the town [sic] (Del Palacio, 1982, f. 40).

Photograph 5 November 20 parade. Guadalupe Victoria, Durango, ca. 1945. Archivo Familia Del Palacio.

As can be seen, and in accordance with the functions that former students of teachers colleges were expected to perform, my father, like many other teachers, was an agent of civility whose work encompassed much more than his school duties: he succeeded in organizing cooperative associations, parades, sport teams, plays, dance performances, modernizing agricultural work and selling in the stores the produce of school farms … These and many others seem to have been his tasks. Besides being the school principal, he was in charge of the adult literacy program in the municipality. He was also a delegate for the PRI and in charge of different organizational committees. That is the time my sister reminisces in a letter to my brother Jaime:

[…] that is how he was in his latter times, turning life into a funny play, such as the ones he performed in the small town theaters when he was young, and when I recall that I also see the young man with the wild hair that from the stage taught a class in morality and manners to the ranchers in a hat and carrying a gun in the town’s cinema […] (Letter from María Elena del Palacio to Jaime del Palacio, August 1985).

Incursions into politics

That position was the last one in my father’s teaching career. He had met General Blas Corral in Cuencamé during Corral’s campaign for the governorship of Durango, and once the general became governor he appointed my father as tax collector in Guadalupe Victoria, in December 1945. He held that wellpaid job until 1950, and my siblings remember those years as the best in their childhood. They were a family with five children that had finally gained some stability, without having to move every year to a new, usually poor, town.

At the beginning of the governorship of Enrique Torres Sánchez, my father had to leave his job, which was by appointment, and attracted by a scheme of one of his former employees he tried to exploit a mine in Zacatecas. He returned to Durango in 1951, penniless. He had already tried to go back to teaching, but he did not last a month in service when General Eligio Villarreal, described by my father as a “very renowned person in Guadalupe Victoria, a farmer and owner of livestock, who had a lot of money” (Del Palacio, 1982, f. 45), offered him a job as Senior Official of the Confederacy of Parties of the Mexican People, who were promoting the candidacy of Miguel Henríquez Guzmán for president of Mexico.

What follows is a brief account of my father’s political activities, which in my opinion cannot be entirely separated from his previous teaching career, since it was thanks to the latter and to the activities he had conducted to promote citizenship in the towns where he had worked that he had both the interest and the skills to work in politics.

Henriquismo is a largely forgotten political movement. “[…] It took shape […] as an attempt at political dissidence within the PRI” (Servín, 2001: 15), which from the opposition articulated the discontent against Miguel Alemán. Henriquistas saw themselves as the true heirs of the Mexican Revolution, whose most recent expression had been President Cárdenas’ legacy. Some of the aims of the movement were “to put a stop to Miguel Aleman’s corruption, to make political practice more democratic, to stop rising prices and inflation, and to recover some essential conquests of the Revolution such as agrarian reform and the defense of Mexico’s sovereignty” (Servín, 2001: 17).

My father did not speak much about his political activities, although fortunately in the archive there are several documents and photographs of them: speeches to people in different towns of Durango and even a manifesto signed by him and copied as a flyer in Durango and Chihuahua, besides some newspaper clippings. He was in charge of organizing the candidate’s visit to the city of Durango. About those activities he said (probably exaggerating a little): “As a leader in the Confederacy of Parties of the Mexican People I did a good job and struggled to help our candidate win. I spared no effort, and earned the votes of almost everyone in the State of Durango. We had a great number of followers: men, women, even commanding officers in the army” (Del Palacio, 1986, f. 48).

My father speaks of men in the military as followers of the movement, starting with General Villarreal, which is true. They had been pushed aside in the regimes of Presidents Manuel Ávila Camacho and Miguel Alemán, and limited in their political participation (Servín, 2001: 19). Among the followers of henriquismo were generals Múgica, García Barragán, and later Cándido Aguilar, when the former Constitutionalist Party joined the movement.

After July 6 1952, it became clear that an electoral fraud had been orchestrated to make Adolfo Ruíz Cortines (the candidate of the PRI) win by claiming he had received 78% of the votes, although the followers of Henríquez counted 3 million votes for their candidate (Del Palacio, 1986, f. 47). Repression followed: on July 7, soldiers dispersed a spontaneous demonstration in Mexico City’s Alameda Central with great violence. The same happened throughout the country, where people where illegally jailed and there were attacks on Henríquez’s followers who, in spite of that, remained defiant and waited for two years for their leader’s signal to take up arms. Henríquez never decided to do it (Servín, 2001). My father was one of the victims of that repression.

So hard did I struggle that I was given a terrible beating by the minions of the governor and the PRI, who took me out of the city to beat me ferociously and, after pushing me out of the car, shot twice at me. Luckily the bullets only scratched me, but the beating was so bad that I was in bed for eight days, without being able to eat because my teeth had been loosened after being hit in the face with a pistol (Del Palacio, 1986, f. 50).

This seems to have happened in December 1954, as can be read in a small note in El Siglo de Torreón:

[…]at the corner of Luna and Arista streets, four men descended from an automobile to threaten, beat and kidnap teacher Francisco del Palacio, Senior Official of the FPPM in the state of Durango, to abandon him later near the aviation field after shooting at him twice at point blank range (El Siglo de Torreón, December 17 1954: 1).

And his was not the only case. My father recounts that many fellow members of his political party were jailed, and sometimes beaten and tortured. This happened all over the country: many henriquistas were even “disappeared” by the police forces (Servín, 2001).

After the cause was lost, my father, ill and defeated, joined my mother in 1955. She had moved with their five children to Mexico City in 1952, tired of the vicissitudes of politics. They began a new life in the capital of the country, far away from their teaching, from political struggle, and especially from their beloved small towns of Durango.

Final words

Memories, photographs and correspondence, both private and official, contained in a family archive, may be a valuable source for the history of everyday life as well as a contribution to the social, political and cultural history of a country. My aim in this paper was to show how the information contained in my father’s autobiography and the photographs in the family archive may show details of everyday life, personal reasons, fears, small achievements in a particular moment of Mexico’s history. Family biography is also valuable insofar as it shows how major historical events had an effect on the lives of specific people. My father’s account of his life as a rural teacher may explain how precarious teacher’s lives were, moving from one town to the next in search of a better salary or running away from danger, how they found their schools virtually destroyed and tried to improve them, and how, using their limited training, they managed to teach others and became agents of social change.

Taking ethnography as my approach, I did not want to leave my own voice out of this analysis. I did not want to pretend to be objective in such a close - almost intimate - story, and more than once I had to rely on my own memory of my parents’ accounts to fill in information that my father did not take into account. Scholarly references were essential to “correct erroneous memories”, as Jelin (2002) would say, since more than once I had to correct dates that my father wrote incorrectly, such as the date of the raid on the indigenous boarding school or the entrance of Villa’s troops into Durango in his childhood. It is not the accuracy of the dates that is important here but the immediacy of the account, which may help to understand history better.

REFERENCES

Avitia Hernández, A. (2013). Historia gráfica de Durango. Los alacranes alzados, historia de la revolución en Durango. Tomos III, IV y V, México: s/e. [ Links ]

___ (2006). El caudillo sagrado. Historia de las rebeliones cristeras en el estado de Durango. México: s/e. <https://www.bibliotecas.tv/avitia/El_Caudillo_Sagrado.pdf> [ Links ]

Blanco, M. (2012). “Autoetnografía, una forma narrativa de generación de conocimientos”. Revista Andamios, 9 (19), 49-74. [ Links ]

Carmona Dávila, D. (2018). “Gonzalo Escobar se levanta contra el gobierno de Emilio Portes Gil, exige respeto a las organizaciones campesinas y obreras del país”. Memoria Política de México. México: Instituto Nacional de Estudios Políticos. <http://www.memoriapoliticademexico.org/Efemerides/3/03031929.html> [ Links ]

Civera Cerecedo, A. (2015). “Normales rurales, historia mínima del olvido”. Revista Nexos, 1 de marzo en <https://www.nexos.com.mx/?p=24304 [ Links ]

Del Palacio, F. (1982). Apuntes históricos y anecdóticos de Francisco del Palacio Zavala (1912-1982). Mecanuscrito inédito. [ Links ]

Ellis, C. (2003). “Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity. Researcher as Subject”. En Denzin, N. y Y. Lincoln (eds.). Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. [ Links ]

Guijosa, M. (2010). Escribir nuestra vida. Barcelona: Paidós. [ Links ]

Iniesta, M. y C. Feixa (2005). “Historia de vida y ciencias sociales. Entrevista a Franco Ferrarotti” Revista de Recerca i Formació en Antropología. Periferia. 5, 1-14, <http://www.periferia.name> [ Links ]

Jelin, E. (2002). Los trabajos de la memoria. Madrid: Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

Legoff, J. (1988). Histoire et Memoire. París: Gallimard. [ Links ]

Lerner, V. (1982). La educación socialista. México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

Lozoya Cigarroa, M. (2000). Leyendas y relatos del Durango antiguo. Durango: s/e. [ Links ]

Medina Esquivel, R. (2018). Minería y escuelas. Familias, maestros, sindicatos y empresas en Cerro de San Pedro y Morales (San Luis Potosí, 1934-1963). El Colegio de San Luis-INEHRM-SOMEHI-DE, en prensa. [ Links ]

Meyer, J. (1993). La cristiada. México: Ed. Contenido. [ Links ]

Pacheco Rojas, J. (2001). Breve historia de Durango. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

Padilla, T. (2009). “Las normales rurales, historia y proyecto de nación”. El Cotidiano, 54, 85-93, <https://www.iteso.mx/documents/11109/0/Normales+en+México.pdf/dedf04e5-d25f4fa5-9b00-ea6694728456> [ Links ]

Palacios Valdés, M. (2011). “La oposición a la educación socialista durante el cardenismo (1934-1940)”. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa. 16, (48) s/p. <http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S140566662011000100004> [ Links ]

Servín, E. (2001). Ruptura y oposición. El movimiento henriquista, 1945-1954. México: Cal y Arena. [ Links ]

Steedman, C. (1993). Past Tenses. Essays on Writing Autobiography and History. Londres: Rivers Oram Press. [ Links ]

Vaughan, M.K. (2000). La política cultural en la revolución. Maestros, campesinos y escuelas en México 1930-1940. México: SEP/Fondo de Cultura Económica. [ Links ]

1I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their very useful suggestions that helped me improve this text.

2This is part of the text of a letter sent by María Elena del Palacio to Jaime del Palacio that accompanies the archive on the history of the two rural teachers who were our parents. The letter is dated in August 1985.

3These groups, as I will explain below, called cristeros in Durango, had discrepancies with other groups under the same name operating in other areas of Mexico. In Durango, cristeros included some mestizo peasants, but mostly indigenous ones from the south of the state (Avitia, 2013, t. IV: 54; 2006), and their motives were not specifically religious but more usually linked to ethnic and territorial resistance.

4Some of these stories are still told, including one about a store owner who, believed to be dead after a terrible illness, was taken to the cemetery. Since it was very late, he could not be buried that day and instead was left at the cemetery’s chapel, where he woke up in the middle of the night and managed to make his way home. When he knocked on the door, his wife was so scared that she died of a heart attack. This and other stories can be found in Lozoya Cigarroa (2000).

5An uprising started by José Gonzalo Escobar on March 3 1929 against President Plutarco Elías Calles, with many followers (reportedly around 30 thousand) mainly in the states of Sonora, Chihuahua, Nuevo León, Coahuila, Durango, Southern Baja California and even Veracruz. In some states, such as Durango, this uprising allied itself to the cristeros. The agraristas who fought against them were under the command of Joaquín Amaro nationwide, while in Durango the socalled Mexican Soviet Revolution under José Guadalupe Rodríguez was instrumental in ending the uprising. (Carmona, 2018; Avitia, 2013; Avitia, 2006; Meyer, 1993).

6The Mexican Constitution was finally modified in 1946 to eliminate the term “socialist education” (Diario Oficial de la Federación, December 30 1946).

7His story, especially in regard to the indigenous boarding school, is told in the novel Rescoldo, los últimos cristeros, written by his son Antonio and considered one of the best novels about the Cristiada (Avitia, 2006).

Received: February 24, 2018; Accepted: July 17, 2018

texto em

texto em