Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Diálogos sobre educación. Temas actuales en investigación educativa

versão On-line ISSN 2007-2171

Diálogos sobre educ. Temas actuales en investig. educ. vol.10 no.18 Zapopan Jan./Jun. 2019

Thematic axis

Ponciano Rodríguez: normalista, editor and public official (1893-1921)

* Ph. D. in History. Research Professor at Universidad Pedagógica Nacional. Mexico. r_menindez@yahoo.com.mx

The nineteenth century was fading away, giving way to a new century full of changes and developments. Modernity invaded Mexico and education was not left out: to the contrary, it was attended to in various aspects: school spaces, programs, textbooks, furniture, schedules, materials and, in particular, teacher training.

Under this idea, teacher colleges - known in Mexico as Escuelas Normales, and their students and alumni as normalistas - were created in the country’s main cities, including Mexico City, Orizaba and Xalapa. In these educational spaces teachers were trained who would later be recognized as scholars of education.1 Some of these college graduates looked for spaces to debate, create and disseminate the modern pedagogical thought they had assimilated.

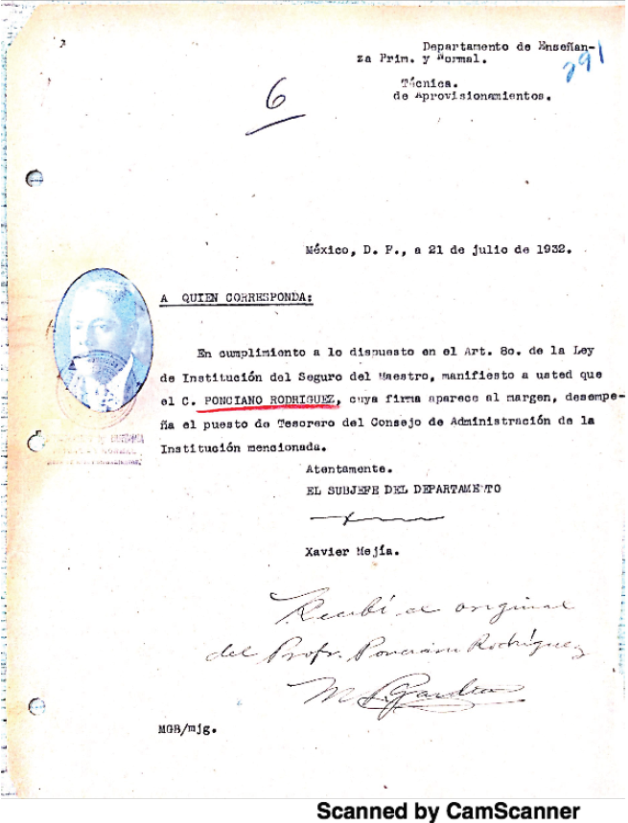

In this article I discuss Professor Ponciano Rodríguez, who had a long career as a teacher and was a member of the educational administration throughout his working life. Through the study and research of different aspects of the life of a teacher, such as their training, production, and professional career, we can learn about and deepen our knowledge of a fine educational space; a teacher’s biography becomes an important anchor to address the educational system of the time, its educational policy, its context and many other spaces of an educational model with tints of modernity.

Keywords: President Porfirio Diaz’s regime; teaching; pedagogical press; modernity

El siglo XIX se desdibujaba dando paso a un nuevo siglo lleno de cambios y novedades. La modernidad invadía el país y la educación no estuvo excluida de este proceso, muy por el contrario, fue atendida en diversos aspectos: espacios escolares, programas, libros de texto, mobiliario, horarios, materiales escolares y, en particular, se miró la formación del magisterio.

Bajo esta idea se crearon escuelas normales en las principales ciudades del país, entre las que destacaron las de la ciudad de México, Orizaba y Xalapa, espacios educativos donde se formaron algunos maestros que, más tarde, serán reconocidos como intelectuales educativos.1 Algunos de sus egresados buscaron espacios para debatir, crear y difundir el pensamiento pedagógico moderno que habían asimilado en las escuelas normales.

En este artículo presento al profesor Ponciano Rodríguez, quien tuvo una larga trayectoria como maestro y fue miembro de la burocracia educativa durante toda su vida laboral. A partir del estudio e investigación de diversos aspectos de la vida de un maestro, como son su formación, producción y vida profesional, podemos conocer y profundizar en un fino espacio educativo; la biografía del maestro se convierte en un importante anclaje para adentrarnos en el sistema educativo de la época, en la política educativa, en el contexto y en muchos otros espacios de un modelo educativo con tintes de modernidad.

Palabras clave: Porfiriato; magisterio; prensa pedagógica; modernidad

Introduction

Ponciano Rodríguez, an alumnus of the Mexico City Teacher College - known in Mexico as Escuela Normal, and their students and alumni as normalistas - began to work as a teacher in 1893. Besides teaching, his career also included being an elementary school principal, a supervisor, head of the 1st and 2nd Sections of the General Directorship of Elementary Education, head of the Rudimentary Instruction Section, and pedagogical inspector. Such a long career in educational administration did not prevent him from conducting other activities, combining his administrative work with his intellectual interests. This article addresses his work as author of pedagogical papers, starting in 1901 as the founder and member of the editorial board of the journal La Enseñanza Primaria, the publication for the divulgation of modern pedagogical thought of the Colegio de Profesores Normalistas de México, and finally member of Mexico’s Higher Council of Public Education in 1902.

My interest in studying this teacher arose from his membership in a network of teachers’ college alumni, some of whom were part of the educational elite during the government of President Porfirio Diaz’s. This group, comprised of professional teachers, would have a significant impact through its publications, lectures, and methods, in Mexico’s turn-of-the-century educational policies. In particular, I will address his participation from 1901 to 1910 in the journal La Enseñanza Primaria. My analysis of this figure will be conducted at three levels: as a teacher, as a public official, and as an author of articles. Each one of these levels will provide valuable information about the different spheres in which he lived and worked.

The methodology followed in this article is part of the social history of education and is based on the analysis of the actors of education, in this case teacher Ponciano Rodríguez.

The sources consulted come from the following archives and libraries: Historical Archive of Mexico’s Ministry of Public Education, Fondo Secretaría de Estado y Despacho de Justicia e Instrucción Pública, Sección Antiguo Magisterio, Serie Personal Profesores, Ponciano Rodríguez, 1886-1940; Fondo Antiguo of the Gregorio Torres Quintero Library of the Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, and the Daniel Cosío Villegas Library in El Colegio de México.

Context

The decade of the 1890s was characterized by an interest of the Mexican state in educational issues. Teacher training was seen as a priority for the government’s educational project and became part of the main objectives of the agenda of Minister Baranda, who gave his approval for the creation of Mexico City’s Escuela Normal de Profesores (Teachers’ College), a project that would be headed by Ignacio Manuel Altamirano. At last, it would not be a project to be filed in the “proposal drawer”. Minister Baranda believed - perhaps unlike any other public official - in the importance and transcendental relevance of training elementary school teacher in accordance with the highest standards. He believed that with good teachers there would be good teaching: “Only the teacher is the living element, whose mission is not limited to communicating information but also a method - and how important this is - and values, along with his personality” (Meneses, 1998: 377).

Starting in 1901 there were important changes in Mexico’s political-educational sphere. Justo Sierra became Undersecretary of Public Instruction, and the political changes had effects in the Escuela Normal. Miguel Serrano, its director for fifteen years, no longer held that position. Outstanding pedagogue Enrique C. Rébsamen, who until then had been the director of the renowned and influential Escuela Normal of Xalapa, was appointed director of the recently created General Directorship of Teacher Training (Dirección General de Enseñanza Normal) on August 24 1901. Several normalistas from Xalapa began to work in this Directorship and were important collaborators in this new project in Mexico City. Some actions were immediately undertaken: a new curriculum was established, and the medical inspection service was created, both in 1902. They worked intensely, but it all came to an end in 1904 when Rébsamen died (Meneses, 1998).

Normalista teacher Alberto Correa took charge of the General Directorship and other activities related to teaching. His normalista education can be seen in his intense work and projection of teacher training. He sought to modernize teaching, to be at the forefront of education, and to position teacher training as a key factor in Mexico’s educational system.

Justo Sierra, a fundamental actor in the educational sphere, included the professionalization of teachers as a special focus of teachers’ colleges, with the aim of having the greatest possible number of teachers trained in the new pedagogy who were knowledgeable in the latest teaching methods, as well as the most modern teaching strategies.

By 1907 there were 26 teachers’ colleges in Mexico. Consequently, the number of their graduates increased. The figures show the new panorama:

The number of teachers increased from 12,748 in 1895 to 21,017 in 1910. The increase of teachers was greater than that of Mexico’s population: in 1895 there were ten teachers for every 10,000 inhabitants and by the Centennial (of Mexico’s War of Independence, in 1910) this number rose to 14. The number of teachers was evidently insufficient to meet the needs of a growing educational sector.” (González Navarro, 1959, p. 606).

In this political and educational context, Ponciano Rodríguez studied at Mexico City’s Escuela Normal de Profesores, carried out his work as a teacher and developed as a professional. His life was determined by his years in the Escuela Normal, his studies, his friends and the net-works he built. The school defined part of his working and intellectual mobility, the two aspects addressed in this article.

Who was Ponciano Rodríguez? Biographical data

He was born in Chimalhuacán, Chalco, State of Mexico, on November 10 1866,

His parents were Nicolás Rodríguez and Francisca Espinoza, two poor peasants from the town. The family emigrated to Mexico City, […] in the capital he had, then, his elementary education, after which he went to the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria in order to obtain an education in the sciences, completing the first two years successfully. But special circumstances forced Young Rodríguez’s family to return to their place of origin, and he had to do farm work. In 1889 the family returned to Mexico City, where he registered at the Escuela Normal. In 1893, after a brilliant exam, he obtained his degree as Teacher, and a position as an Annex School Assistant. In 1901 he began to serve the schools that depended from the General Directorship of Elementary Education as an Elementary School Principal; a year later he was appointed Higher Elementary School Principal, and a few months later School Inspector and Member of the Higher Council of Public Education.2

Upon finishing his studies, teacher Rodríguez immediately began to work, and as mentioned above he started as an assistant teacher. That was the beginning of a meteoric career. Between 1893 and 1921 he worked as an assistant teacher in the Elementary School Annex of Mexico City’s Escuela Normal de Maestros and assistant teacher at the Escuela Nocturna Complementaria No. 5, also in Mexico City, principal of the Escuela Primaria Elemental No. 63 in Mexico City and the Primaria Superior No. 1 in Azcapotzalco, pedagogical inspector in elementary schools outside Mexico City and then in Mexico City, twice, head of the second and first sections of the General Directorship of Elementary Education, successively, principal of the Elementary School Annex of Mexico City’s Escuela Normal de Maestros twice, head of the Rudimentary Instruction Section of the Ministry of Public Instruction and Fine Arts, teacher of General and Special Methodology of Spanish and Arithmetic at Mexico City’s Escuela Normal de Maestros, and teacher of Arithmetic, Algebra, Geometry and Trigonometry at the same school. In 1921 he worked as an Algebra and Trigonometry teacher at the Escuela Normal de Maestros (AHSEP, Box 30,000, File 3) (See Annex 1).

His work as an educator was combined with his work at the Colegio de Profesores Normalistas in Mexico City, of which he was a founder and president. The Colegio’s divulgatory publication was the journal La Enseñanza Primaria, in which Rodríguez participated as a founding collaborator, was part of the editorial board and wrote several articles on pedagogy. He wrote about different topics, but especially about textbooks, pedagogical issues, and the teaching of natural science (See Chart 1).

Chart 1 Articles published by Ponciano Rodríguez

| TITLE | TOPIC | JOURNAL | VOLUME | ISSUE | DATE | COUNTRY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disciplina Escolar | Discipline at school | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 2. | July 15, 1901 | Mexico |

| Las palabras Normales | Grammar | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 3. | August 1, 1901 |

Mexico |

| La Pedagogía y el Maestro en la Educación General |

Pedagogy | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 5. | September 1, 1901 |

Mexico |

| El desarrollo mental | Mental

Calculation Mathematics |

La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 6. | September 15, 1901 |

Mexico |

| Los libros de texto en la escuela primaria |

Textbooks | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 7. | October 1, 1901 |

Mexico |

| Los libros de texto

y los programas |

Textbooks | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 9. | November 1, 1901 |

Mexico |

| Los exámenes | Education and teaching | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No.10. | November 15,1901 |

Mexico |

| El método en los

libros de texto |

Textbooks | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 11. | December 1,1901 |

Mexico |

| Las primeras palabras de un libro de texto |

Textbooks | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 13. | January 1 1902 |

Mexico |

| Los cuestionarios en

los libros de texto |

Textbooks | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 15. | February

1 1902 |

Mexico |

| Ignacio M. Altamirano | Teachers | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 19. | April 1 1902 | Mexico |

| Las palancas en las

lecciones de cosas |

Lessons on things | La Enseñanza Primaria | I | No. 21. | May 1 1902 | Mexico |

Source: the author, with data from the journal La Enseñanza Primaria.

The fact that Ponciano Rodríguez was an alumnus of Mexico City’s Escuela Normal, along with his being part of the important group of pedagogues led by Torres Quintero, were two elements that enabled him to join a network with links to political power that succeeded in having an impact on educational policies thanks to their pedagogical knowledge.

The Colegio de Profesores Normalistas of Mexico City: a formative space for normalista teachers

Francisco Larroyo points out that pedagogical theory in Mexico went through three stages: the first one from the enactment of the Organic Law of Instruction (Ley Orgánica de Instrucción, 1867-1869) to 1880; the second, which includes the Pedagogical Congresses (1889-1891) and the work of Rébsamen and his disciples, and the third, at the beginning of the twentieth century, marked by the work of Gregorio Torres Quintero and his group, including the normalistas Celso Pineda, Daniel Delgadillo, Lucio Tapia, Luis de la Brena, Ponciano Rodríguez, José María Bonilla, Jesús Sánchez, Juan José Barroso, Toribio Velasco and Francisco Angulo (1973). This third phase may be considered the stage of the consolidation of modern pedagogy. I will focus on the latter group, and especially on Ponciano Rodríguez, although it must be pointed out that they were all normalistas, most of them alumni of Mexico City’s Escuela Normal. They all held positions in the educational administration as officials, principals, inspectors or public school teachers.

Intellectual leaders such as Enrique Rébsamen and Gregorio Torres Quintero, creators of new teaching methods, were at the forefront of the normalista elite. Torres Quintero’s leader-ship helped consolidate a group of normalistas who would create the Colegio de Profesores Normalistas in Mexico City. Ponciano Rodríguez was its founder and president. The Colegio expanded with the foundation of the journal La Enseñanza Primaria, whose editorial board included Luis de la Brena, Gregorio Torres Quintero, Celso Pineda and Ponciano Rodríguez. The journal became the main organ for the divulgation of the normalistas’ pedagogical thinking. It had a long very successful life, and was distributed in Mexico as well as other countries (see Image 1). From Torres Quintero’s group, Ponciano Rodríguez was the only one who did not write textbooks, although he did write a number of articles published in La Enseñanza Primaria and in El Magisterio Nacional, a publication of Mexico City’s school inspectors directed by Julio S. Hernández.

The fact that the articles published by Ponciano Rodríguez were not many leads me to think that his main role in the journal was as an editor, so I conducted a thorough examination of the articles published in the journal with the aim of learning about the interests and ideas of the group of normalistas who made up its editorial board, which I present in the next section.

La Enseñanza Primaria: topics of the articles selected by its editorial board

The teachers who had studied at the recently created Escuelas Normales sought spaces to express themselves and divulgate the pedagogical ideas they had received and assimilated in these schools. The normalistas were aware of the importance of having a publication, which meant they had a channel to divulge their pedagogical thinking and, at the same time, a space of authority and power. The journal was therefore aimed mainly at teachers and their chief audience was normalistas, students, and especially “empirical” teachers (teachers without formal training), whose only access to new knowledge being generated about education in Mexico and abroad was these materials. At the dawn of the twentieth century, Gregorio Torres Quintero’s group moved steadily towards inserting themselves in different areas of education in Mexico. Their goals included not only teacher training and updating outside the classrooms, but also to insert themselves in the realm of educational policy. This became an ambitious but achievable goal for a group that became stronger and made progress in its proposals for education.

Celso Pineda held the position of editor and headed the publication for ten years. In its final years he was effectively its director. The editorial board was wholly made up of normalista teachers. Among the publication’s founding members were teachers Celso Pineda (editor), Luis de la Brena and Ponciano Rodríguez.3 Together with Gregorio Torres Quintero, they made the journal a successful publication. Soon other teachers joined them: Daniel Delgadillo, Julio S. Hernández, Toribio Velasco and José Juan Tablada. As part of the editing team were José María Bonilla, Lucio Tapia, Jesús Sánchez and José Juan Barroso. The names of Antonio Santa María, Carlos Flores, Manuel Velázquez Andrade and Francisco Montes de Oca would later be added to this list (La Enseñanza Primaria).

There is no doubt that the journal’s beginning was auspicious. The number and variety of authors published grew with the passage of time. Foreign authors and women had a presence that made the journal a pioneering publication on educational topics aimed at teachers. The women collaborators were few, but highly regarded in the field of education. The journal’s long life began in 1901 and ended in 1910, shortly before the armed uprising.

Which were the topics of interest and concern for these normalistas and one of the journal’s closest collaborators, Ponciano Rodríguez? The articles published show that there were at least four lines of interest.

The first line that supported the body of the journal, and also the strongest one, had to do with school subjects and the official contents of elementary education. In its first issue in 1901, 61 articles about these areas were published, while 31 articles addressed other topics. In 1902 64 articles were about school subjects and 32 on other topics. In 1909-1910 89 articles linked to school subjects were published. Although there was a decrease when new lines of interest were opened, such as legislation on education, project for pre-schools, public speaking, labor issues, school materials and school discipline, it is worth mentioning that there was more advertising for materials, school furniture and textbooks in the journal.

The following are some examples of topics and titles of articles related to them:

Gymnastics / Physical Education: “¿Atletismo o vigor?”; Mental Calculations: “Cálculo mental para primer año”; Lessons on things: “Una esponja, lecciones de cosas”; Morals: “A un ocioso”; Cosmography: “La luna no tiene atmósfera”; Grammar: “Las palabras normales”; Arithmetic: “Los complementos de diez”; Civic instruction: “Deberes del ciudadano y del mexicano”; Artistic Education: “La educación artística”; History of Mexico: “La obra de Hidalgo”; Geography: “El valle de México”; Physics: “Grados de solidez y liquidez de los cuerpos”; Spanish: “El análisis del estudio de la lengua materna”; Geometry: “Medición de superficies”; Manualities: “Trabajos manuales: los dos métodos fundamentales para la enseñanza”; Biology: “Marcha general de la sangre en los mamíferos y aves”; Writing: “La letra inglesa en la escuela primaria”; Reading: “La cuestión de la lectura. Discusión de algunos principios”

The contents that stand out in the journal are those about subjects such as morality, Reading and writing, history of Mexico, lessons about things, calculations, poetry, Spanish, grammar, geography, arithmetic, school hygiene, civic instruction, biology, gymnastics, mathematics, singing, physics, algebra, and cosmography.

These data show that, for a member of the editorial board like Ponciano Rodríguez, a priority was scientific topics, with 99 articles published, followed by morality and history of Mexico, with 62 articles.

The interest of the normalistas revolved around four lines, in the following order: promoting a scientific education, knowledge of the mother tongue, an education in history, and civic and patriotic values through a culture of duties supported by the contents of morality, geography, civic instruction and hygiene. Another aspect considered was the promotion of physical education: gymnastics and an education in hygiene were highly valued. All of this was done with the aim of fostering a scientific and pragmatic education. The articles constitute materials both useful and necessary for teachers to conduct their classes, and they are therefore didactic support. Some are quite good and very practical in that respect. Toribio Velasco wrote an article titled “La preparación de clases” (“Preparing a class”). Not only that: teachers were educated and enriched with articles that broadened their view and information on a given topic. We can see how they addressed complex moral issues such as moral stories and suicide, or very specific ones about grammar such as homophones and spelling exercises. There are also texts aimed at generating new behaviors and habits, such as “La inspección médica y la higiene en la escuela” (“Medical inspection and school hygiene”), and very necessary ones due to modernizing trends: a class on the description of stamps.

The second line was about the topics of the new pedagogy. It was necessary to show the new guidelines and teaching methods to all the teachers, especially “empirical” teachers and those who taught in rural or isolated communities. Teaching and learning needs were present in all these articles. Their goal was to give teachers tools for their work. Some examples are “Los exámenes” (“Exams”), “La Pedagogía a pequeñas dosis” (“Pedagogy in small doses”), “La enseñanza cíclica” (“Cyclical teaching”), “Pedagogía de los trabajos de aguja” (“Teaching needlework”), “Organización escolar. Entrevista con un pedagogo” (“The organization of schools: an interview with a pedagogue”) and “Reformas escolares posibles y económicas” (“Possible and economical school reforms”).

The third line comprised articles on textbooks, to which several articles were devoted in a year. Some of them were “Los libros de texto en la escuela primaria” (“Textbooks in elementary education”), “Los libros de texto y los programas” (“Textbooks and programs”), “El método en los libros de texto” (“Method in textbooks”), “Los cuestionarios y los libros de texto” (“Questionnaires and textbooks”). Another aspect of this topic was the advertising in the journal, which manifested itself in three ways: 1) the promotion of publishing houses such as Casa Bouret or Editorial Herrero Hermanos, Sucesores; 2) articles entitled “Opiniones de la prensa” (“Opinions of the press”), most of which promoted with their praise the normalistas’ textbooks, and 3) the “Notas bibliográficas” (“Bibliographical notes”) that had the same goal, that is, to promote the normalistas’ textbooks.

The fourth line was concerned with teaching and included articles related to topics of interest for teachers, such as labor law, new appointments, history of education, school discipline, past and modern teaching, the evolution of teaching and teachers in Mexico, and public speeches such as the one given at the inauguration of the Colegio de Profesores Normalistas de la Ciudad de Mexico on January 6 1900. Other articles discussed the lack of teachers in Baja California and other states, part-time teachers, methodological academies, lectures, morning assembly, the National Congress on Educación, pedagogical associations, bibliographic notes, regulations such as the “Reglamento del Colegio de Profesores Normalistas de Mexico y el papel de un director” (“Regulations of the Colegio de Profesores Normalistas de México and the role of a principal”). Also featured were advertisements for school materials and textbooks.

The main objective of this group of normalistas was to uphold and divulge a pedagogical model that placed the child at the center, with a comprehensive education that included a focus on its moral, physical, intellectual and aesthetic aspects. Their pedagogical approach was linked to their political one, headed by Justo Sierra. The Law on Education of 1908 determined that there would be a shift from instruction to education since the former was part of the latter, and elementary education would be compulsory. Sierra notes that “[...] the State must be in charge of finding in the child the physical, moral and intellectual man, must strive for a harmonic development of the child’s faculties, of these three modes of being and add another, the aesthetic one; that is, educate the ability to conceive the beautiful and shape taste.” (Sierra, 1985: 25).

Article 4 of the Law of Elementary Education of 1908 included the following precepts that would regulate the future of Mexico’s educational policy: moral education would help shape character through obedience and discipline, as well as the constant and rational exercise of feelings, resolutions and actions aimed at building self-respect and love for the family, school, country, and the others. Physical education would be obtained through indispensable prophylaxis, adequate physical exercise and the creation of hygiene habits. Intellectual culture could be achieved through the gradual and methodical exercise of feelings and attention, the development of language, the discipline of imagination and a continuous approach to accuracy in judgements. Finally, aesthetic education would be fostered by promoting the elements of good taste and providing students notions of art suitable for to their age (Bazant, 1993:43).

The guidelines mentioned above show the interest and concerns of the journal’s editors, among whom Ponciano Rodríguez played an outstanding role in the selection of articles and in making contacts to include new authors and up-to-date educational topics for teachers.

Some final ideas

Ponciano Rodríguez was part of a group of normalistas who were characterized especially by establishing networks, especially with fellow normalistas; their nexus was leading thinkers such as Enrique Rébsamen and Gregorio Torres Quintero. They all had distinguished careers after they graduated from Mexico City’s Escuela Normal, where they began to build the networks they would later strengthen. Confident in their knowledge, they demanded teaching positions and obtained them. Their mobility was remarkable, as long as they were normalistas. Mexico’s federal government was interested in their professional profile and promoted them especially because, since it did not have direct influence on the states, these educators would have the task of disseminating and expanding the new educational model throughout the country.

It is important to point out how, starting with journals published in Mexico City such as La Enseñanza Primaria, these teachers’ and thinkers’ ideas began to be divulged throughout the country and had a considerable influence on educators.

These teachers were given the task of writing methodological guides, textbooks and articles for pedagogical journals such as La Enseñanza Primaria. They were the ones who selected the contents and the topics on which they should write and which should be divulgates.

In this cohort of pedagogues, Rodríguez rose from his work as a teacher to positions of inspector, elementary school principal and Section head. In all these spaces he succeeded in divulgating new knowledge, methodology, and textbooks (most of them written by normalistas in Mexico City and other states in the country) among the community of normalistas and “empirical” teachers who were in such great need of materials, articles and information for their classroom practice.

The armed uprising of 1910 had profound consequences for this group of teachers from Porfirio Díaz’s regime, as was the case of Ponciano Rodríguez and other normalistas. However, after many struggles and troubles, they managed to find a place in the new schools of the Revolution and in the emerging educational system, and this allowed them not only to obtain a retirement pension but, more importantly, to leave behind a legacy built in the years of the Porfirio Díaz regime, opening the way for a modern educational project in which they played a unique role and whose influence and repercussions would last until the 1930s.

REFERENCES

Archivo Histórico de la Secretaría de Educación Pública, Fondo Secretaría de Estado y Despacho de Justicia e Instrucción Pública, Sección Antiguo Magisterio, Serie Personal Profesores, México. [ Links ]

Fondo Antiguo y Colección Especial. Biblioteca Gregorio Torres Quintero, Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, México. [ Links ]

Hemeroteca Digital, Universidad Autónoma de México, Revista La Enseñanza Primaria (1901-1910). [ Links ]

REFERENCES

Arroyo, F. (1973). Historia comparada de la educación en México. México: Porrúa. [ Links ]

Bazant, M. (1993). Historia de la educación durante el porfiriato. México: El Colegio de México. [ Links ]

_____ (2018). “Retos para escribir una biografía” en Revista Secuencias, Instituto Mora, Núm. 100 Diccionario Porrúa (1970). Historia, Biografía y Geografía de México. México: Porrúa. [ Links ]

Diccionario Porrúa (1970). Historia, Biografía y Geografía de México. México: Porrúa [ Links ]

Galván, L.E. (1981). Los maestros y la educación pública en México. Un estudio histórico. México: Nacional Impresora. [ Links ]

González Navarro, M. (1959). “El porfiriato. La vida social”. En D. Cosío Villegas (ed.). Historia moderna de México (4). México: Editorial Hermes. [ Links ]

Meneses, E. (1998). Tendencias educativas oficiales en México 1821-1911. México: Centro de Estudios Educativos/Universidad Iberoamericana. [ Links ]

Meníndez, R. (2012). “Los proyectos educativos del siglo XIX”. Revista Estudios. Filosofía, Historia, Letras. México: Instituto Tecnológico Autónomo de México. [ Links ]

Moreno Gutiérrez, I.L. (2002). “La prensa pedagógica en el siglo XIX”. En L.E. Galván Lafarga (coord.). Diccionario de Historia de la Educación en México. México: Conacyt/CIESAS. [ Links ]

_____ (2011). “Los maestros intelectuales educativos 1889-1910”. Ponencia presentada en el XI Congreso Nacional de Investigación Educativa / 9 Historia e Historiografía de la Educación. México: Consejo Mexicano de Investigación Educativa, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. [ Links ]

Sierra, J. (1985). “Reformas legales a la educación primaria”. Debate pedagógico durante el porfiriato. Antología preparada por Mílada Bazant. México: El Caballito/SEP. [ Links ]

1A concept defined by Leticia Moreno, “Los maestros, intelectuales educativos 1889-1910”, in XI Congreso Nacional de Investigación Educativa Historia e Historiografía de la Educación. Consejo Mexicano de Investigación Educativa, A.C., Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, 2011.

Received: February 28, 2018; Accepted: June 27, 2018

texto em

texto em