Introduction

Weight stigma (WS) is defined as a social devaluation and denigration of an overweight or obese person (Tomiyama et al., 2014). It represent a socially acceptable form of discrimination (Vartanian, Pinkus & Smyth, 2014) that produces prejudice and discrimination (Aramburu & Louis, 2002). During the last decade, this experience and the prevalence of self-reported discrimination associated with WS has become more frequent among overweight and obese people (Andreyeva, Puhn & Brownell, 2008; Friedman et al., 2005; Hatzenbuehler, Keyes & Hasin, 2009).

The WS has been documented in multiple areas, including the occupational, educational, health and interpersonal contexts (Latner, Puhl & Stunkard, 2012; Puhl & Brownell, 2006). The victims of WS report that frequently they are object of negative beliefs such as being less competent, socially isolated, responsible of obesity and lacking of self-discipline (Brady, 2016; Olander et al., 2013; Puhl & Heuer, 2009; Schmalz & Colistra, 2016; Wadden et al., 2000). The evidence shows that stigmatization sources are family members, healthcare professionals, strangers, and coworkers (Puhl & Brownell, 2006; Puhl & Heuer, 2010; Vartanian et al., 2014). For instance, it has been reported that physicians and other health care professionals have implicit anti-fat bias (Aramburu & Louis, 2002; Teachman & Brownell, 2001), which in turn is associated with less empathy and lower expectations about the effectiveness of lost weight interventions (MacLean et al., 2009; Phelan et al., 2015; Schwartz, Chambliss, Brownell, Blair & Billington, 2003).

The WS can have negative impact at several levels (Brewis, Sturtz-Sreetharan & Wutich, 2018; Jackson, 2016). At psychological level, victims of WS self-reported a great impact on the psychological well-being (Sikorski, Luppa, Luck & Riedel-Heller, 2015), self-esteem and self-efficacy (Ebneter, Latner & O’Brien, 2011; Himmelstein & Tomiyama, 2015). At physiological level, it may also exacerbate the obesity increasing psychological stress and cortisol production (Friedman et al., 2005; Latner et al., 2012; Myers & Rosen, 1999; Tomiyama et al., 2014). And at behavioral level, it does increase the preference for high fat or sugary food (Major, Hunger, Bunyan & Miller, 2014; Puhl & Brownell, 2006) and lack of physical activity (Vartanian & Novak, 2011; Vartanian & Shaprow, 2008), thus the person can gain weight or have difficulties to lost it (Ashmore, Friedman, Reichmann & Musante, 2008; Puhl, Moss-Racusin & Schwartz, 2007; Schvey, Puhl & Brownell, 2011; Tomiyama et al., 2014).

Given the impact that WS has for overweight and obese individual, it is important to have validated instruments evaluating people´s experiences associated with WS. One of the most commonly used measures is the Stigmatizing Situations Inventory (SSI; Myers & Rosen, 1999). The SSI is a fifty-items version scale asking for specific situations of stigmatization based on weight. The items were created by asking to obese people to identify stigmatizing situations they used to faced, and later requesting to a team of psychology raters to select those who were more representatives of WS situations. Thus, Myers and Rosen identified 11 dimensions: Comments from children, Comments from strangers, Comments from family, Comments from doctor, Being excluded, Being stared at loved ones, Being embarrassed by your size, Negative assumptions that people make, Physical barriers or obstacles, Job discrimination, and Physical violence.

Nevertheless, we identify several limitations in the original scale developed by Myers and Rosen (1999). For instance, the length of the scale becomes a complication when the scale must be used in combination with other scales or when a brief measure is needed; some of the dimensions identified by Myers and Rosen are not culturally suitable for Latinos, and to our knowledge there is no analysis of its psychometric properties reported previously. Subsequently, Vartanian (2015) developed two brief 10-items scales (SSIa and SSIb) based on Myers and Rosen measure. These short versions kept several dimensions proposed in the original measure, such as being stared at public, comments from children and physical barriers. Although both measures have been widely used in the U.S., there is no Spanish version available for Latinos living in South-America neither a measure culturally adapted to measuring WS. Therefore, the aim of this study was to validate a brief Spanish version of SSI in a sample of Chilean adults.

Method

Participants

University faculty and staff working at Universidad de La Frontera were eligible to participate. Using a non-probabilistic sampling and convenience technique, we enrolled 400 participants in a three-year follow-up study that aimed to identify psychosocial predictors of metabolic syndrome. Despite the fact that we have three data points available, for this article we analyzed cross-sectional data obtained from the second wave of the study. Thus, the sample at second wave comprised 377 adults (Mage = 45.0, SD = 8.7), 62% female, with a mean body mass index (BMI = kg/m2) of 27.8 (SD = 4.0). Using a ladder for measuring subjective socioeconomic position, 56% rated themselves as middle socioeconomic status. Twenty-three percent finished high school, 22% was graduated from a technical institute, and 19% obtained a master degree. Twelve percent self-reported a monthly income below 250,000 Chilean pesos (~US dollars = 410), 60% an income between 250,000 and 1,000,000 (~US dollars = 411 and 1.64), and 28% an income greater than 1,000,000.

Instruments and measures

Stigmatizing Situations Inventory (Myers & Rosen, 1999). We adapted and validated the SSI to the Chilean context, following this procedure. First, from the items available in the two brief versions (SSIa and SSIb) proposed by Vartanian (2015), and the items available in Myers and Rosen manuscript, we dropped out repeated items and used in total 24 items. Second, using a method of committee translate, Psychologists (PhD) and doctoral students from a Doctoral Program in Psychology, back-translated from English to Spanish, and semantically adapted the items to the Chilean culture, keeping the dimensions proposed by Myers and Rosen: Comments from children, Negative assumptions, Physical barriers, Being stared at, Comments from doctors, Comments from family, Comments from others, Avoided, excluded or ignored, Loved ones embarrassed by you size, and Job discrimination. Third, because we were interested in a short version of the SSI, we finally asked to an independent group of psychology raters to select 10 items that most repeatedly occurs to Chilean overweight and obese people. Thus, we obtained a short version, representing seven out of 10 dimensions proposed originally by Myers and Rosen. According to the raters, the dimensions Job discrimination, Loved ones embarrassed by your size, and Avoided, excluded or ignored are not frequent neither culturally acceptable for Chileans; thus, these dimensions were excluded.

The version developed by Vartanian (2015), aimed to identify WS experience that could have happened at least once in the life, therefore, items are rated on a 10-point scale (0 = “never”, 1 = “once in your life”, 2 = “several times in your life”, 3 = “about once a year”, 4 = “several times per year”, 5 = “about once a month”, 6 = “several times per month”, 7 = “about once a week”, 8 = “several times per week”, and 9 = “daily”). Nevertheless, we adapted this rate on an 8-point scale excluding options “once in your life” and “several times in your life”, since we were interested in measuring weight stigma situations occurring during the last year, as well as avoiding memory bias recall. According to empirical and theoretical considerations, and 8-point scale provides enough variance in the responses, reduces distortion due to extreme score bias, and facilitates the process of discrimination between several answer options (Morales, Urosa & Blanco, 2003; Revilla, Saris & Krosnick, 2014). Therefore, in our scale, all items were rated on the 8-point scale: 0 = “never”, 1 = “about once a year”, 2 = “several times per year”, 3 = “about once a month”, 4 = “several times per month”, 5 = “about once a week”, 6 = “several times per week”, and 7 = “daily”.

Everyday Discrimination Scale (Williams, Yu, Jackson & Anderson, 1997). Participants were asked to answer nine questions related to daily life discrimination experience (e.g., “people act as if you are dishonest”). The answers were scored on a 6-point range (1 = “never”; 6 = “almost every day”). Likewise, the participants had to identified the motive for being discriminated against, for instance appearance, color of skin, sex, weight, etc. (α = .89).

State-Trait Personality Inventory (Spielberger, Gorsuch, Lushene, Vagg & Jacobs, 1983). Participants answered 10 anger trait item (e.g., “I have a fiery temper”), and 10 anxiety trait items (e.g.,“I feel nervous and restless”). Answers were scored from 1 = “almost never” to 4 “almost always”. Two reliable sum scores were calculated (α = .83 and .87, respectively) and used in the analyses. This scale has been previously validated in Chile (Pavez, Mena & Vera, 2012).

Anthropometrics measures. BMI was calculated with weight and height [weight (kg)/weight (mts)2]

Sociodemographic characteristics. The participants self-reported age, sex, educational attainment, income, and their subjective socioeconomic position.

Procedure

The institutional board of the Universidad de La Frontera approved this study. First, participants were invited to the Laboratory of Stress and Health, where a trained graduate student from the Doctoral Program in Psychology explained the purposes of the study and obtained written informed consent from participants. Then, trained research staff members from our Laboratory obtained anthropometric measures. Finally, Participants completed psychological measures with an online questionnaire.

All participants were economically compensated with 10,000 Chilean pesos (~20 U.S. dollars). Participant’s records/information was de-identified prior to analysis.

Data analysis

First, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis (EFA), and then a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). We randomly selected 173 participants from the total sample of 377 to provide data for the EFA. We executed the EFA with a principal component extraction and oblimin rotation. Factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were selected. Items with factorial loadings lower than .50 were dropped out.

Once we obtained a satisfactory solution, we conducted a CFA with the remainder data (n = 204), based on the theory of Bentler and Weeks (1980). Because the Mardia’s multivariate normality assumptions was not met, the robust ML test which correct for non-normal data is reported. The proposed factor structure was evaluated using several indicators (Ullman & Bentler, 2013): Robust comparative fit index (CFI > .90) and Tucker Lewis index (TLI > .90), standardized root mean square (SRMR < .06), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .08). Given the non-normal multivariate data distribution, all the fit indices were adjusted with Satorra-Bentler (SB) correction (Satorra & Bentler, 2001).

The concurrent validity between WS situations and other measures was tested with the Pearson correlation test. Therefore, we compute a SSI total score, and then tested it association with a total daily life discrimination score, total anger and anxiety score, and BMI. All analyses were conducted with STATA 14.2, using a nominal alpha equivalent to .05.

Results

The minimum amount of data needed for EFA was met, with a sample of 173 participants, providing a ratio of over 17 observations per variable. We satisfied the measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = .90); the Bartlett´s test of sphericity was statistically significant (x2 (45) = 1574.84, p < .001). We used principal component extraction because we were interested in identify a single factor underlying the 10-items of the SSI. The initial eigenvalues indicated a solution with two factors, explaining 67% and 11% of the variance, respectively. All items had a strong primary loading greater than .7 in the first factor, but five items had cross-loadings factors that were lower than .5 in the second factor. After performing an oblimin rotation we obtained a similar solution. Because, the second factor had eigenvalues just over one, and all items had a strong primary loading greater than .7 in the first factor (see Table 1), we kept the 10 items and decided for a single factor solution.

Table 1 Exploratory factor analysis: Factorial loadings.

| Items | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | .76 | .48 |

| 2 | .78 | .48 |

| 3 | .83 | .40 |

| 4 | .85 | |

| 5 | .75 | |

| 6 | .77 | |

| 7 | .79 | .46 |

| 8 | .84 | .41 |

| 9 | .89 | |

| 10 | .89 |

Note. Blank spaces represent loadings < .30

We estimated the reliability of the single solution, with both alpha´s Cronbach and omega coefficient’s. As depicted in Table 2, the item-test correlations were all greater than .65. The reliability was high (α = .93 and ω = .95).

Table 2 Items in English/Spanish, item-test correlations, and factorial loadings.

| Items | Item-test correlation | Factorial loading |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Child make fun of you because of your weight / Los niños se burlan de mi por mi peso | .74* | .78* |

| 2. Other people having low expectation of you because of your weight / Las personas tienen bajas expectativas (esperan poco) de mi por mi peso | .76* | .80* |

| 3. Having people assume you have emotional problems because you are overweight / Porque tengo sobrepeso, la gente piensa que tengo problemas emocionales | .80* | .84* |

| 4. Having people assume you overeat or binge eat because you are overweight / Porque tengo sobrepeso, la gente piensa que como en exceso o como grandes cantidades de comida | .86* | .85* |

| 5. Not being able to find clothes that fit / No encuentro ropa de la talla que necesito | .76* | .75* |

| 6. Being stared at in public / Siento que la gente me mira por mi peso | .75* | .78* |

| 7. Having a doctor recommend a diet, even if did not come in to discuss weight lost / El médico me ha recomendado una dieta, pese a que lo he visitado por un problema de salud que no se relaciona con mi peso | .81* | .77* |

| 8. A doctor blaming unrelated physical problems on your weight / He tenido un médico que relaciona cualquiera de mis problemas de salud con mi peso | .85* | .82* |

| 9. A parent or other relative nagging you to lost weight / Me he molestado porque un familiar cercano insistentemente me ha dicho que baje de peso | .89* | .88* |

| 10. Having strangers suggest diets to you / Una persona desconocida me ha sugerido que baje de peso | .90* | .88* |

* p < .001

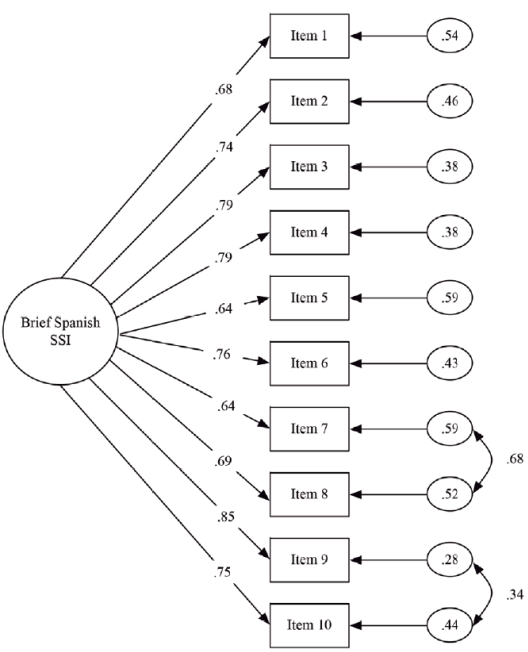

The CFA suggests a single factor structure grouping the 10-items. The factorial loadings are all greater than .60, ranging from .64 and .85. According to Lagrange multiplier test, we introduced a couple of covariance, between errors of items 7 and 8 (.68), and errors of items 9 and 10 (.34); see Figure 1. The overall fit indices for this model are excellent (SB x 2(33) = 43.21; p < .05; RMSEA = .03; CFI = .98; TLI = .97; SRMR = .05). The solution obtained explained 92% of the variance.

Figure 1 Confirmatory factor analysis: Single factor solution. SSI = Stigmatizing Situations Inventory.

We obtained evidence for the concurrent validity of the SSI and several measures. Thus, the SSI was associated with BMI (r = .43, p < .05), anger (r = .19, p < .05), anxiety (r = .29, p < .05), and daily life discrimination (r = .26, p < .05).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to validated a brief Spanish version of the SSI in a sample of Chileans adults. Specifically, we aimed to determine the reliability and the validity of this brief Spanish version of the SSI.

Our results suggest that the brief Spanish version of the SSI is a reliable scale with one dimensional factorial structure, that is associate with several psychological variables and BMI. To our knowledge, this is the first version validated measuring obesity stigma in a sample of Latinos non-living in the U.S. Although our version is a brief scale of 10-items similar to others used in the U.S. (Vartanian, 2015), this version was adapted to the Chilean people taking into consideration cultural characteristics. Thus, for example, the dimension Job discrimination is not included in the final version because Chilean people in a working place do not explicitly discriminate against other by weight. Further, the dimensions Loved ones embarrassed by your size and Avoided, excluded or ignored were also excluded from the measure because it is not frequent that Chilean families recognized explicitly feeling embarrassed by the weight of their beloved; thus, making complex for the stigmatized people, in these situations, to attribute the discrimination to their size.

The brief Spanish version of the SSI has several advantages. First it can be easily used by different healthcare professionals, allowing to detect another health-related variable that can be associated with health outcomes such as obesity. Similarly, it can be used by researchers studying psychological consequences of obesity. Second, it is a reliable and valid scale easily understandable by participants. Third, a total score can be obtained by summing the 10-items. Finally, it allows for the identification of several stigmatizing situations frequents for this overweight and obese people occurring during the last year.

This study has some limitations. First, although, this scale measures stigmatization situations, it does not allow to identify consequences of such stigmatization. According to previous studies being exposed to WS impact on self-esteem (Friedman et al., 2005; Murakami & Latner, 2015), anxiety and depressive symptoms (Himmelstein & Tomiyama, 2015), as well as on physical health (Tomiyama et al., 2018). Therefore, for future studies it will be relevant to include measures of internalizing stigma, as well as other psychological measures such as psychological stress, coping, and depressive symptoms, just as it has been recently conducted in other studies (Hayward, Vartanian, & Pinkus, 2017, 2018). Second, our sample mean age was 44 years old making complex to generalize these results to a younger sample. Hence, caution is needed if this scale is used with a younger sample. Moreover, for future studies it will be necessary to determinate the psychometric properties of this scale with a different age sample.

text new page (beta)

text new page (beta)