Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de trastornos alimentarios

versión On-line ISSN 2007-1523

Rev. Mex. de trastor. aliment vol.2 no.2 Tlalnepantla jul./dic. 2011

Artículos

Factores predictores del tratamiento de la bulimia nerviosa con Terapia Interpersonal

Predictors of Interpersonal Psychotherapy in patients with bulimic eating disorders

Jon Arcelus1,2, Jonathan Baggott1, Debbie Whight1, Lesley McGrain1, Lesley Meadows1, and Christopher Langham1

1 Eating Disorders Service, Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust, Leicester General Hospital, Leicester, UK.

2 Loughborough University Centre for Research into Eating Disorders (LUCRED). School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, Leicestershire, UK.

Correspondencia:

Eating Disorders Service,

Brandon Unit, Leicester General Hospital

Gwendolen Road, Leicester LE5 4PW.

Tel: 0116 2256230.

E-mail: J.Arcelus@lboro.ac.uk

Recibido: 07/08/2011

Revisado: 25/09/2011

Aceptado: 27/09/2011

Resumen

Objetivo: Determinar los factores de pronóstico del tratamiento de la bulimia nerviosa con terapia interpersonal.

Diseño: 80 pacientes con el diagnostico de Bulimia Nerviosa (BN) o trastornos del comportamiento alimentario no especificados con características de BN (TCANE) fueron tratados con 16 sesiones de terapia interpersonal. Los pacientes fueron evaluados utilizando una entrevista semi-estructural (Clinical Eating Disorders Rating Instrument-CEDRIC). También completaron una batería de cuestionarios para evaluar los niveles de estima personal (Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale -RSE), la psicopatología de los trastornos de la alimentación (Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire-EDE-Q), la función interpersonal (Inventory of Interpersonal Functioning-IIP-32) y los niveles de depresión (Beck Depression Inventory-BDI).

Método: El pronóstico de interés fue definido por la variable de remisión y recuperación. Para el análisis del estudio se realizaron una serie de regresiones logísticas.

Resultado: Baja estima personal, y una menor patología en la función interpersonal fueron los factores de peor pronóstico.

Conclusión: Aunque la terapia interpersonal es un tratamiento efectivo para las personas que sufren de bulimia nerviosa, los pacientes con estas patologías con baja estima personal y menos problemas interpersonales deberían de ser tratados con otro tipo de terapia.

Palabras clave: Terapia interpersonal, Bulimia Nerviosa, TCANE, Pronóstico.

Abstract

Objective: To determine predictors of treatment outcomes in patients with Bulimic Eating Disorders treated with Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT).

Design: Following initial assessment, 80 patients with diagnoses of Bulimia Nervosa or Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS), entered treatment in the form of 16 sessions of IPT. Patients were assessed using a validated semi-structure interview (Clinical Eating Disorders Rating Instrument-CEDRIC) and completed measures of self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale-RSE), eating psychopathology (Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire-EDE-Q), interpersonal functioning (Inventory of Interpersonal Functioning- IIP-32), and depression (Beck Depression Inventory-BDI).

Method: Remission and recovery after 16 sessions of IPT were the two outcomes of interest. Univariate analysis and a series of backwards stepping logistic regressions were performed to determine the variables associated with remission and recovery.

Result: Low self-esteem and less interpersonal problems were the main predictors of poor outcome.

Conclusion: As patients with Bulimic Disorders with low levels of interpersonal problems and high levels of low self-esteem are likely to do less well with IPT, different type of treatment should be offered to them. A randomized controlled trial could explore this hypothesis in more detail.

Key words: Interpersonal Psychotherapy, Bulimia Nervosa, EDNOS, Predictors.

Introduction

Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) was developed for the treatment of depression and was manualised in 1984 (Klerman, Weissman, Rounsaville, & Chevron, 1984). The work of Meyer (1957) and Bowlby (1969) provided the theoretical underpinnings of IPT, which is a focused time-limited psychotherapy which concentrates on problems of an interpersonal nature in the "here and now". Since the conception of IPT, the original manual has been updated (Weissman, Markowitz & Klerman, 2000, 2007) and several manuals have been written concerning modifications of IPT, including those for depressed adolescents (Mufson, Dorta, Moreau, & Weissman, 2004), the elderly (Hinrichsen & Clougherty, 2006), perinatal women (Weissman et al., 2000), bipolar disorder (Frank, 2005), social phobia (Hoffart et al., 2007), dysthymic disorder (Markowitz, 1998) and finally bulimia nervosa (IPT-BN; Fairburn, 1993).

IPT-BN was not developed systematically through an adaptation from IPT for depression, but instead was discovered to be effective when used as a control treatment for CBT during a randomised controlled trial for individuals with BN (Fairburn et al., 1991). IPT was not adapted specifically for BN in the treatment trial, and beyond limited initial psychoeducation, eating problems were not addressed during the treatment. It was hypothesised that as IPT shared some non-specific factors with CBT, its inclusion in the trial would highlight the benefits of cognitive behavioural techniques in CBT that were not present in IPT. However, while CBT was considered most effective, IPT also resulted in the improvement of eating disorder symptoms. This discovery led to the further development of IPT-BN as a viable treatment option, and it was manualised in 1993 (Fairburn, 1993).

Since its conception, IPT has been compared to CBT, the current treatment of choice, with equally positive results in both individual and group settings (Fairburn, 1997; Fairburn, Jones, Peveler, Hope, & O'Connor, 1993; Fairburn et al., 1991; Fairburn, Wilson, & Kraemer, 2000; Roth & Ross, 1988; Wilfley et al., 1993). Agras, Walsh, Fairburn, Wilson, & Kraemer (2000) found that CBT was superior to IPT at the end of treatment however there was no significant difference between the two treatments at one year follow-up. Based on these findings, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for eating disorders in the UK (NICE, 2004) recommends IPT as an alternative to CBT for the treatment of BN as long as patients are informed that it could take longer that CBT to achieve comparable results. The IPT team in Leicester, UK, added the psycho-educational and cognitive elements (such as directive techniques, modeling, problem solving, decision analysis and role-play) back into the therapy (Whight et al., 2011). This Leicester IPT model for the treatment of Bulimic Eating Disorders has shown to make significant improvements in patients with Bulimic Eating Disorders in terms of patients eating disordered cognitions and behaviours, interpersonal functioning and levels of depression (Whight et al., 2011).

The aim of this study is to identify factors that may predict outcome following treatment with IPT. We hope that this will help clinicians in identifying patients who will benefit from this model of therapy. As severity of main disorder (Feske, Frank, Kupfer, Shear, & Weaver, 1998), pre-treatment self-esteem levels and depression (Baell & Wertheim, 1992; Davis, McVey, Heinmaa, Rockert, & Kennedy, 1999; Fairburn, Kirk, O'Connor, & Anatasiades, 1997) and several dimensions of personality (Ruiz et al., 2004; Westen, Novotny, & Thompson-Brenner, 2004) have shown to predict outcome in psychiatric patients treated with psychotherapy, we hypotheses that patient with high levels of low self-esteem, high levels of severity of their eating disorder (measured by eating disorders symptoms and length of the illness) and high levels of depression will have worse outcome following treatment with IPT. We will focus on these variables as all have shown strong empirical support in identifying predictors of psychotherapy.

Method

Setting

The Leicester IPT team is part of a specialist National Health Service (NHS) eating disorders service. It offers assessment and treatment of adults (over the age of 18 years) with an eating disorder (Anorexia Nervosa (AN), Bulimia Nervosa (BN) or Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS)). At the time the study took place the IPT team consisted of five level-D IPT therapists (supervisory level) and one level-B IPT therapist. All six therapists provided therapy to patients in the study. In order to maintained consistency throughout the therapy all therapists were trained in IPT and had regular supervision from an accredited IPT supervisor.

Participants

For this study, patients with a diagnosis of BN and those with a diagnosis of EDNOS of the Bulimic subtype will be described as patients with Bulimic Disorders. As the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for Eating Disorders recommends that in the absence of evidence to guide the management of EDNOS, the clinician should follow the guidance on the treatment of the eating problem that most closely resembles the individual patient's eating disorder (NICE, 2004), patients with bulimic disorders will be treated with IPT. Patients with Bulimic Disorders treated with Interpersonal Psychotherapy during a period of 2 years (November 2007-2009) were invited to participate in the study.

The study was approved by the Research and Development Department from the Leicestershire Partnership NHS Trust.

Measures

Clinical Eating Disorders Rating Instrument (CEDRI— Palmer, Christie, Cordle, Davies, & Kenrick, 1987). The CEDRI is a structured investigator-based interview that measures eating-related behaviours and attitudes. This instrument was used to reach an eating disorder diagnosis in accordance with DSM-IV criteria —AN, BN or EDNOS— (APA, 1994). This tool has been shown to have good reliability and validity (Palmer et al., 1987). The CEDRI will be used in the study to identify suitable patients.

Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q) (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994). This is a widely used self-report measure of eating disorder psychopathology (Mond, Hay, Rodgers, & Owen, 2007). Derived from the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) interview (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993), the EDE-Q provides a comprehensive assessment of the specific psychopathology of eating-disordered behaviour in a brief (36-item) self-report format. The EDE-Q produces an overall score and four different sub-scales: Restraint, Weight Concern, Eating Concern, and Shape Concern. For this study the total overall EDE-Q score and the sub-scale of Restraint concern will be used. This questionnaire also provides information regarding binge eating behaviour, which includes the frequency of objective binges, self-induced vomiting, laxative and diuretic use. These measurements are assessed over the previous 28 days. The overall score of the EDE-Q and the scores of the sub-scales are not related to the frequency of bingeing and purging behaviour. Acceptable internal consistency, test–retest reliability and longer-term temporal stability of the EDE-Q have been established (Mond et al., 2007; Reas, Grilo, & Masheb, 2006).

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSE, Rosenberg, 1965). This widely used self-report questionnaire comprises 10 items that are used to generate a global self-esteem score. The items are given in a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores denote lower self-esteem and a score of 3 and above is Rosenberg's criterion for low self-esteem. The RSE has an extensive and acceptable reliability (internal consistency and test-retest) and validity (convergent and discriminant) information exists for the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991).

Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). This is a 21-item questionnaire which provides a measurement for depression. Each item consists of four statements representing increasing degrees of severity with scores ranging from 0 to 3. Patients select the statement that best described themselves in the previous 2 weeks. Scores can range from 0 to 63, with higher scores indicating higher levels of pathology. A cut-off score of 10 or higher is widely used to screen for clinically significant depression (Beck et al., 1961). The BDI has been extensively tested for content validity, concurrent validity, and construct validity. The BDI has also been extensively tested for reliability, following established standards for psychological tests published in 1985. Internal consistency has been successfully estimated by over 25 studies in many populations. The BDI has been shown to be valid and reliable, with results corresponding to clinician ratings of depression in more than 90% of all cases (Beck & Steer, 1984; Beck, Steer & Garbin, 1988).

The Inventory of Interpersonal Problems -IIP-32 (Barkham, Hardy, & Startup, 1996). This is a shortened version of the Inventory of Interpersonal Problems (IIP; Horowitz, Rosenberg, Baer, Ureno, & Villasenor, 1988). The original IIP comprises 127 items representing a comprehensive list of interpersonal problems reported at intake by clients seeking psychotherapy (Horowitz & Vitkus, 1986). The IIP-32 was derived by selecting the four highest-loading items from eight factors that had previously been identified from a factor analysis of the original IIP (Barkham, et al., 1996). The factors are named: Hard to be Assertive, Hard to be Sociable, Hard to be Supportive, Too Caring, Too Dependent, Too Aggressive, Hard to be Involved and Too Open. Barkham et al., (1996) demonstrated that the factor structure could be confirmed in an independent sample and found that the factor-based subscales had adequate internal consistencies and retest reliabilities even in a general population sample. The IIP-32 (Barkham et al., 1996) contains 19 questions phrased as 'It is hard for me to' , followed by, for example, 'be assertive with another person' or 'make friends' . The remaining 13 items are phrased as 'These are things I do too much' , followed by, for example, 'I fight with other people too much' , or 'I am too dependent on other people' . A five point response format is provided ranging from 'not at all' (0) through 'a little bit' (1), 'moderately' (2), 'quite a bit' (3), to 'extremely' (4). A full-scale score is calculated as the mean rating over all 32 items. Eight subscale scores are also calculated as the mean of the four items that loaded highest on their respective factors when the IIP-32 was developed. High scores indicate a high degree of interpersonal problems. The overall internal consistency of the inventory is high (0.86) (Barkham et al., 1996).

The therapy. The Leicester model of IPT consists of 16 weekly sessions of 45 minutes duration. The initial four sessions are broadly a detailed assessment of the patient's eating disorder symptomatology and mood with a specific focus on the interpersonal context. The initial sessions are also used to provide psycho-education regarding patients' eating disorder and associated symtomatology. At the send of the assessment sessions an interpersonal formulation is reached and the focal area is chosen that will form the basis of the work of the middle sessions (sessions 5-14). IPT recognizes four focal areas: interpersonal role disputes, interpersonal role transitions, complicated grief, and interpersonal deficits (sometimes called interpersonal sensitivity). The middle sessions will work with the focal area with the patient. Eating disorder and depressive symptoms are tracked in each session and any changes are linked to the interpersonal focus. Specific techniques used during these sessions include: communication analysis, clarification, exploration, encouragement of affect, use of the therapeutic relationship and behavioural change techniques. The final two sessions (sessions 15-16) prepares the patient to end the therapy. Contingency planning for the future and relapse prevention work are also areas that are addressed during the last 2 sessions (Arcelus, Haslam, & Whight, 2011, Whight et al., 2011).

Analysis of the data.

Definition of remission and recovery

Outcome was measured by analysing the frequency of bingeing and purging behaviour. Patients were defined as having their condition remitted if they binged or purged less than twice per week over the previous 28 days. Recovered status was determined by patients who did not binge or purge at all over the previous 28 days as identified in the EDE-Q. These criteria for defining clinical outcome are comparable to other remission and recovered criteria reported in the literature (Agras et al., 2000).

Predictors variables

The potential effect of the severity of the illness were examined with the overall scores of the EDE-Q, scores of the Restraint subscale and length of illness. In addition, we examined the impact of the general psychopathology as measured by the scores of the BDI and RSE and the severity of the interpersonal problems by analysing the overall scores of the IIP-32.

Statistical Analyses

Patients were assessed using the semi-structured interview (CEDRI) to reach a clinical diagnosis. At assessment patients were invited to complete a series of questionnaires as explained above (RSE, EDE-Q, IIP-32 and BDI). Patients who fulfilled diagnostic criteria for a Bulimic Disorder were offered 16 sessions of IPT. Patients repeated the EDE-Q following treatment. Intention to treat analysis was used, where the data from T1 are brought forward to T2 in cases where questionnaires were not completed at the end of therapy for each variable for every participant.

The outcome of interest was whether patients remitted or recovered after 16 sessions of IPT. Univariate analysis was performed to determine the variables associated with remission and recovery. Comparisons were conducted using non-parametric tests. Those variables that were significant, or nearly so (p< 0.2), were entered into a forward stepwise multiple regression with remission or recovery after 16 sessions as the dependent variable. In the second stage of data analyses, we conducted a series of backwards stepping logistic regressions in order to explore the contribution of each variable, while statistically controlling for the effects of all other variables included in the model, to the prediction of patients' remission and recovery status. The first set of predictors included those variables that differentiated non-remitters from remitters and between recovered and non-recovered in our earlier analyses, with the critical alpha set at < 0.20. Significance was determined using nominal alpha (p≤0.05). All analyses were performed using SPSS 16.0.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of patients

Out of the 84 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study, 74 (88.1%) patients agreed to participate in the study. Of the 74 patients, three (4.6%) were male. The mean age was 27.6 years (SD= 7.7), length of illness 8.4 (SD= 5.4), age of onset of the eating disorder 20.6 years (SD=5.9) and BMI 24.9 (SD=6.0). In spite of Leicestershire being a multi-racial area (29.9% of Asian or Asian British origins, 2001 Census) the vast majority of the young people studied were white (n=59, 79.7%), eight (10.8%) were Indian, three (4.1%) were Pakistani, two (2.7%) Chinese and two (2.7%) Black-Caribbean. Out of the 74 patients who participated in the study, 33 (44.6%) patients suffered from BN and 41 (55.9%) from EDNOS Bulimia subtype. The results of the questionnaires at assessment are shown in table 1.

Predictor variables

Out of the 74 patients who commenced therapy, 59 (79.7%) of them concluded 16 sessions of IPT. Following therapy the condition of more than half of the patients who concluded therapy had remitted (N=41, 69.5%) and 14 (23.7%) recovered.

Predictors of remission

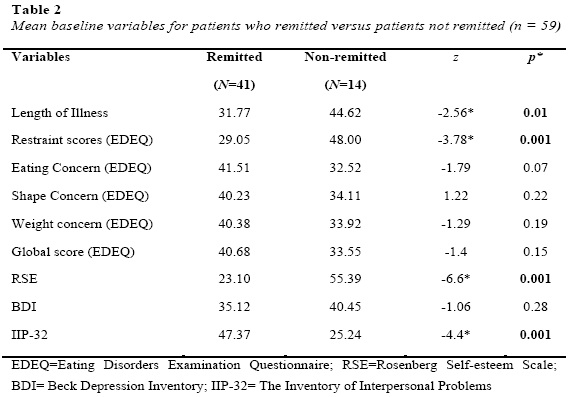

When comparing patient's characteristics, and eating disorders psychopathology between the group of patients whose condition remitted with patients whose condition had not remitted, the study found that there was a statistical significance in the following variable: length of illness, restraint score of the EDE-Q, total score of the IIP-32 and RSE score at assessment. See table 2.

Logistic regression analysis

Length of illness, Restraint Sub-scale score of the EDE-Q, IIP-32 and RSE score distinguished remitters from non-remitters in the univariate analyses. Those variables were then examined in a series of backwards stepping logistic regressions. Following stepwise elimination of variables that failed to predict remission status at the 0.25 alpha-level, the four independent variables (length of illness, scores of the RSE, Restraint sub-scale of the EDE-Q and total IIP-32 score) remained significant predictors of remission status (p < 0.05). The full model containing those four predictors was statistically significant, χ² (4, N-74)= 75,45, p<0.001, indicating that the model was able to distinguish between patients whose symptoms remitted and patients whose symptoms did not remitted. The model as a whole explained between 63.9% (Cox & Snell R Square) and 85.6% (Nagelkerke R Squared) of the variance of remission status and correctly classified 95.9% of the cases. As shown in Table 3, two of the independent variables made a unique statistically significant contribution to the model (RSE and IIP-32). The stronger predictor of a patient to have their condition remitted after 16 sessions of IPT, was the value of the IIP-32, recording an odds ratio of 8.62. This indicated that respondents with high levels of interpersonal problems at assessment were eight times more likely to respond to treatment than those who did not.

Predictors of recovery

Following the same analysis as above it was found that three independent variables (Restraint scores of the EDE-Q, RSE values and IIP-32), were significant predictors of recovery status (p< 0.05). The full model containing those three predictors was statistically significant, χ² (3, n-74)= 27.4, p<0.001 and the model as a whole explained between 31% (Cox & Snell R Square) and 49.9% (Nagelkerke R Squared) of the variance of recovery status and correctly classified 83.8% of the cases. As shown in Table 4, none of those variables made a unique statistically significant contribution to the model. This means that none of the variables could predict who was able to recover from their eating disorder after 16 sessions of IPT.

Discussion

There has been a sense amongst clinicians that although IPT has been shown to be effective in treating Bulimia Nervosa, some of its principle components had been lost in previously published research trials (Fairburn et al., 1993; Fairburn et al., 1995; Agras et al., 2000). In these studies any resemblance of techniques that might be considered to have cross over with CBT were removed from the IPT-BN model. The Leicester model essentially puts these original IPT techniques back and applies them to treat Bulimic Disorders (Arcelus et al., 2011, Whight et al., 2011). A recently published paper using this treatment modality suggested that although patients respond to IPT, there are a considerable number of patients whose symtomatology remains following treatment (Arcelus et al., 2009). The aim of this study was to explore factors that could predict outcome following IPT therapy in patients with Bulimic Disorders. The study focuses on three main predictor variables selected from the literature: severity of the symtomatology, general psychopathology and interpersonal factors.

The study found that following therapy nearly 70 % of the patients had improved to the point of remission, whilst 30% had not. When exploring this, the study found that those patients who did not improve tended to have lower interpersonal problems, longer length of illness, lower self-esteem and higher levels of restraining behaviour. When analyzing this data in detail, severity of the interpersonal problems were found to be the main predictor of improvement post IPT. This will indicate that patients with Bulimic disorders who have lower interpersonal issues are likely to do less well with IPT. This could be explained by the fact that this therapy targets specifically interpersonal problems, based in the theory that there is relationship between the bulimic symptomatology and the interpersonal problems.

The study also confirms a number of studies in the field of psychotherapy that have found that pre-treatment self-esteem levels predict outcome of treatment for bulimia nervosa (Baell & Wertheim, 1992; Davis, et al., 1999; Fairburn, et al., 1997). Self esteem is notoriously difficult to change and is rarely improved over the course of brief time limited therapies. The study also found that those patients with severe restrictive behaviour do less well than patients with low levels of restriction. This may indicate that, as found in previous research studies (McIntosh et al., 2005), patients with anorexic like disorders do not respond well to this version of IPT, although further studies are necessary.

Examining predictors of psychotherapy outcome are essential for two main reasons, firstly to aid the shaping of therapy and secondly to identify suitable patients for specific treatment modalities. This last point is particularly important when working in clinical settings with patients who suffer with eating disorders. The NICE guidelines for eating disorders (NICE 2004) recommend that patients with Bulimia Nervosa should be treated with CBT or IPT, without clear recommendations when to use each therapy. There is a clear cost difference in the training required to become an IPT or a CBT therapist, and therefore availability.

This study is limited by the small number of patients studied, and the lack of control treatment. As with many studies looking into predictors of outcome, the results are also limited by the variables selected. Future projects should explore more in depth predictors of outcome using a mix of qualitative and quantitative methodology as a part of a Randomized Control Trial.

References

Agras, W.S., Walsh, T., Fairburn, C.G., Wilson, G.T., & Kraemer, H.C. (2000). A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57, 459-466. [ Links ]

American Psychiatric Association (2004). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. [ Links ]

Arcelus J, Haslam M & Whight D. (2011) Interpersonal psychotherapy as a treatment for bulimia nervosa. In: P. Hay, Eds New Insights into the prevention and treatment of Bulimia Nervosa. London: Intech [ Links ]

Arcelus, J., Whight, D., Langham, C., Baggott, J., McGrain, L., Meadows, L., and Meyer. C. (2009). A case series evaluation of a modified version of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) for the treatment of bulimic eating disorders: a pilot study. European Eating Disorders Review, 17, 260-269 [ Links ]

Baell, W.K., & Wertheim, E.H. (1992). Predictors of outcome in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31, 330–332. [ Links ]

Barkham, M., Hardy, G., & Startup, M. (1996). The IIP-32: a short version of the inventory of interpersonal problems. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 32, 21–35. [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R.A. (1984). Internal consistencies of the original and revised Beck Depression Inventory. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 1365-1367. [ Links ]

Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A, & Garbin, G. M. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review , 8, 77-100. [ Links ]

Beck, A.T., Ward, C.H., Mendelson, M., Mock, J., & Erbaugh, J. (1961). An inventory for Measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 4, 561–71. [ Links ]

Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.) Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes, Volume I. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [ Links ]

Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss, Vol 1, London: Hogarth Press. [ Links ]

Davis, R., McVey, G., Heinmaa, M., Rockert, W., & Kennedy, S. (1999). Sequencing of cognitive behavioural treatments of bulimia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 25, 361–374. [ Links ]

Fairburn, C.G. (1993). Interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. In New applications of interpersonal therapy, G.L. Klerman & M.M. Weissman (Eds.), pp. (278–294). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press [ Links ]

Fairburn, C.G. (1997). Interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. In Handbook of treatment for eating disorders, D.M. Garner & P.E. Garfinkel (Eds.), pp. (278–294). New York:Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Fairburn C.G., & Beglin, S.J (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16, 363–370. [ Links ]

Fairburn, C.G., & Cooper, Z (1993). The Eating Disorder Examination. In: C.G.Fairburn & G.T. Wilson (Eds), Binge eating: Nature, assessment and treatment (12th ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

Fairburn, C. G., Jones, R., Peveler, R. C., Carr, S. J., Solomon, R. A., O'Connor, M. E., Burton, J., & Hope, R. A. (1991). Three psychological treatments for bulimia nervosa: A comparative trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 48, 463-469. [ Links ]

Fairburn, C. G., Jones, R., Peveler, R.C., Hope, R. A., & O'Connor, M. (1993). Psychotherapy and bulimia nervosa: longer-term effects of interpersonal psychotherapy, behavioral psychotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50, 419–428. [ Links ]

Fairburn, C.G., Kirk, J., O'Connor, M., & Anatasiades, P (1997). Prognostic factors in bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26, 233–234. [ Links ]

Fairburn, C.G., Norman, P. A., Welch, S. L., O'Connor, M. E., Doll, H. A., & Peveler, R.C (1995). A prospective study of outcome in bulimia nervosa and the long term effects of three psychological treatments. Archives of General Psychiatry, 52,304-12. [ Links ]

Fairburn, C. G., Wilson, G. T., & Kraemer, H. C. (2000). A multicenter comparison of cognitive-behavioural therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 5, 459-466. [ Links ]

Feske, U, Frank, E, Kupfer, D.J., Shear, K., & Weaver, E. (1998). Anxiety as a predictor of response to interpersonal psychotherapy for recurrent major depression: an exploratory investigation. Depression and Anxiety, 8, 135–141. [ Links ]

Frank, E. (2005). Treating bipolar disorder: A clinician's guide to interpersonal and social rhythm therapy. New York: Guilford [ Links ]

Hinrichsen, G.A., & Clougherty, K.F. (2006). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed older adult. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [ Links ]

Hoffart, A., Abrahamsen, G., Bonsaksen, T., Borge, F.M., Ramstad, R., Lipsitz, J., & Markowitz, J.C. (2007). A residential interpersonal treatment for social phobia. New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc. [ Links ]

Horowitz, L.M., Rosenberg, S.E., Baer, B.A., Ureno, G., & Villasenor, V.S. (1988). Inventory of interpersonal problems: psychometric properties and clinical applications. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 885–892. [ Links ]

Horowitz, L.M. & Vitkus, J. (1986). The interpersonal basis of psychiatric symptoms. Clinical Psychology Review, 6, 443-469. [ Links ]

Klerman, G.L., Weissman, M.M., Rounsaville, B., & Chevron. E (1984). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for depression. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Markowitz, J. C. (1998). Interpersonal Psychotherapy for Dysthymic Disorder. Washington, D.C: American Psychiatric Press. [ Links ]

McIntosh, V.V., Jordan, J., Carter, F.A., Luty, S.E., Mckenzie, J.M., Bulik, C.M., Frampton, C., & Joyce, P.R. (2005). Three psychotherapies for anorexia nervosa: a randomized, controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry; 162, 741–747. [ Links ]

Meyer, A. (1957). Psychobiology: A science of man. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas. [ Links ]

Mond, J.M., Hay, P.J., Rodgers, B., & Owen, C (2007). Self-recognition of disordered eating among women with bulimic-type eating disorders: A community-based study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39,747–753. [ Links ]

Mufson, L., Dorta, K.P., Moreau, D., & Weissman, M.M. (2004). Interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents, New York: Guildford press. [ Links ]

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2004). Eating disorders: core interventions in the treatment and management of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and related eating disorders; a national clinical practice guideline. London: National Institute for Clinical Excellence. [ Links ]

Palmer, R.L, Christie, M., Cordle, C., Davies, D., & Kenrick, J (1987). The Clinical Eating Disorders Rating Instrument (CEDRI); a preliminary description. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6, 9-16. [ Links ]

Reas, D.L., Grilo, C.M., & Masheb, R.M (2006). Reliability of the eating disorder examination questionnaire in patients with binge eating disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 43–51. [ Links ]

Rosenberg, M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [ Links ]

Roth, D.M. & Ross, D. R. (1988). Long-term cognitive-interpersonal group therapy for eating disorders. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy, 38, 491-510. [ Links ]

Ruiz, M.A., Pincus, A.L., Borkovec, T.D., Echemendia, R.J., Castonguay, L.G., & Ragusea, S.A. (2004). Validity of the inventory of interpersonal problems for predicting treatment outcome: An investigation with the Pennsylvania practice research network. Journal of Personality Assessment, 83, 213–222. [ Links ]

Weissman, M. M., Markowitz, J. C., & Klerman, G. L. (2000). Comprehensive guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books. [ Links ]

Weissman, M. M., Markowitz, J. C., & Klerman, G. L. (2007). Clinicians quick guide to interpersonal psychotherapy. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Westen, D., Novotny, C.M., & Thompson-Brenner, H. (2004). The empirical status of empirically supported psychotherapies: Assumptions, findings, and reporting in controlled clinical trials. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 631–663 [ Links ]

Wilfley, D. E., Agras, W. S., Telch, C. F., Rossiter, E. M., Schneider, J. A., Cole, A.G., Sifford, L., & Raeburn, S. D. (1993). Group cognitive-behavioral therapy and group interpersonal psychotherapy for the non-purging bulimic individual: A controlled comparison. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61, 296-305. [ Links ]

Whight, D., McGrain. L., Baggott, J., Meadows L., Langham, C., & Arcelus. J. (2011). Interpersonal psychotherapy for bulimia nervosa (IPT BNm). London, UK:Troubador Ltd. [ Links ]