Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.13 no.71 México Mai./Jun. 2022 Epub 22-Ago-2022

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v13i71.1191

Research Article

Diversity and structure of shadow trees associated with Coffea arabica L. in Soconusco, Chiapas

1Cuerpo Académico en Recursos Forestales, Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas, Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas. México.

2Escuela de Doctorado Internacional, Universidad de Santiago de Compostela. España.

3Escuela de Ciencias y Procesos Agropecuarios Industriales, Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas. México.

The traditional systems in the coffee (Coffea Arabica) producing areas develop in shady ecosystems with a wide diversity of flora and fauna species. At present, the original floristic composition has been modified by changes in the establishment of a species Inga spp. Therefore, the importance of knowing the diversity and current tree structure of the agroforestry system in coffee cultivation in Soconusco, state of Chiapas arises. For this aim, 10 sampling units (SU) were randomly established in the middle region of Soconusco Chiapas, with dimensions of 1 000 m2 (20 m x 50 m). Variables were recorded to identify their vertical and horizontal stratification, and importance value indexes (IVI), tree species diversity, Shannon-Wiener and Simpson were calculated. 23 tree species were found out of a population of 279 trees and the plantations with the highest chronological age present greater diversity and tree structure. The observed vegetation presents the lower strata ranging from <9 m and upper > 18 m. The species with the greatest presence in the SUs were Tabebuia donnell smithii, Inga micheliana, Cordia alliodora and Cedrela odorata and, according to the Simpson and Shannon diversity indexes, the vegetation that prevails has little tree species diversity. The highest importance value index came from Tabebuia donnell smithii and Inga micheliana.

Key words Shadow trees; biodiversity; structure; diversity indices; Inga spp.; agroforestry systems

Los sistemas tradicionales en las zonas productoras de café (Coffea arabica) se desarrollan en ecosistemas bajo sombra, con amplia diversidad de especies de flora y fauna. En la actualidad, la composición florística original se ha modificado por cambios en el establecimiento de Inga spp. Por lo anterior, surge la importancia de conocer la diversidad y estructura arbórea actual del sistema agroforestal en el cultivo de café en el Soconusco, Chiapas. Para tal fin se establecieron 10 unidades de muestreo (UM) al azar en la región media del Soconusco Chiapas; con dimensiones de 1 000 m2 (20 x 50 m). Se registraron variables para identificar su estratificación vertical y horizontal, y se calcularon los Índices de valor de importancia (IVI), diversidad de especies arbóreas, Shannon-Wiener y Simpson. Se identificaron 23 especies arbóreas de una población de 279 árboles; a las plantaciones con mayor edad cronológica les correspondió mayor diversidad y estructura arbórea. La vegetación observada presentó estratos inferiores de <9 m y los superiores de >18 m. Los taxones con más presencia en las UM fueron Tabebuia donnell smithii, Inga micheliana, Cordia alliodora y Cedrela odorata. De acuerdo con los índices de diversidad de Simpson y Shannon-Wiener, la vegetación prevaleciente tiene poca diversidad de especies arbóreas. El mayor Índice de Valor de importancia se registró en Tabebuia donnell smithii e Inga micheliana.

Palabras clave Árboles de sombra; biodiversidad; estructura; índices de diversidad; Inga spp.; sistemas agroforestales

Introduction

There is a wide diversity of agroforestry systems (Sánchez-Gutiérrez et al., 2016) in Mexico. considered an option to favor water harvesting (López et al., 2013), conserve the soil (Pérez-Nieto et al., 2012), improve its fertility (Geissert et al., 2017), regulate the microclimate (Villavicencio, 2013), protect and preserve biodiversity (Moguel and Toledo, 2004) and facilitate pest and disease management (Pérez-Fernández et al., 2016). In addition, tree cover generates environmental benefits (Aguirre-Cadena et al., 2016) such as carbon sequestration (Salgado-Mora et al., 2018), which contributes to climate change mitigation, and in the case of the Coffea arabica L. system, grain quality is improved (Farfán, 2014).

Coffee production in Mexico is carried out in a traditional way under the canopy of complex vegetation, diverse in strata and species, similar to the natural forest (García-Mayoral et al., 2015). These ecosystems are rich in flora and fauna (Moguel and Toledo, 2004), and the fruit trees, timber and other multipurpose species in them, are used for shade, as well as for medicinal purposes and firewood (Reyes-Reyes and López- Upton 2003). The species are associated in a spatial and chronological arrangement (Sáenz et al., 2010: Casanova-Lugo et al., 2016) and induce ecological and economic interactions simultaneously or temporally in a sequential manner (Beer and Somarriba, 1999; Krishnamurthy and Ávila 1999), in addition to being compatible with the sociocultural conditions of the region and becoming beneficial to their ways of life.

At present, the biological diversity of shade species in coffee plantations has decreased considerably, as the recommendation to establish monospecific shade with species of the Inga genus (Fabaceae) has been follwed.

With this background, the objectives of the present study were established: to know the importance of the diversity and structure of the trees that predominate as shade associated with Coffea arabica, and to determine the diversity, the value indexes of importance, density, dominance and relative frequency. of the associated vegetation.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The study was carried out in the Huehuetán municipality of the state of Chiapas, Mexico, which is located in the Soconusco region at 15°30'35" N and 92°24'27'' W at 35 masl. The climate is Am(w’’)ig, which corresponds to warm sub-humid with summer rains. The average annual rainfall is 2 800 mm and the average temperature is 28.5 °C. (Garcia, 1973). The soils belong to the two main groups, Acrisol and Luvisol (INEGI, 2005).

Sampling sites

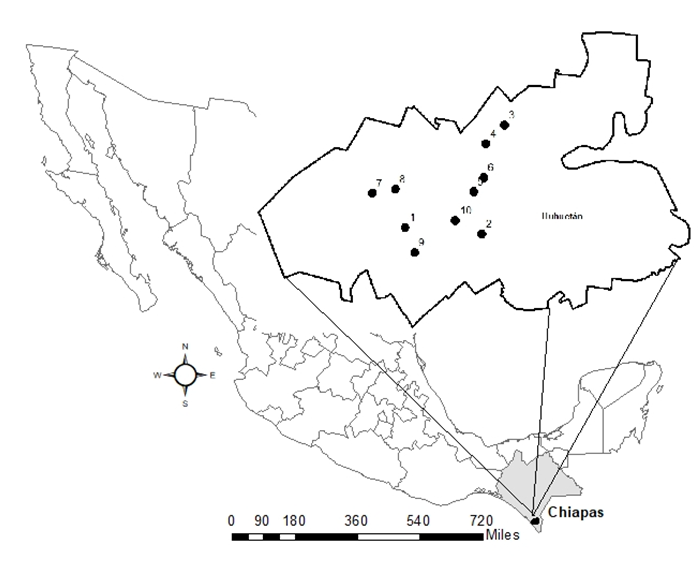

10 random sampling units (UM) were established above the intermediate part of the Huehuetán municipality (from 80 to 540 masl), where coffee cultivation predominates (Figure 1). Each experimental site or sampling unit was named according to the name of the ejido or the cantón (Table 1). Within each one, an area of 1 000 m2 (20 m x 50 m) was set aside based on what was recommended by Cox (1981) and Somarriba (1999) for tree communities in agroforestry systems.

Table 1 Sampling locations of the vegetation associated with the cultivation of Coffea arabica L. in Soconusco, Chiapas.

| UM* | Location | Altitude (masl) |

Geografic Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Longitude X | Latitude Y | |||

| 1 | Ejido Tepehuitz | 520 | 92°28´19.63´´ | 14°59´27.81´´ |

| 2 | Cantón El Búcaro | 300 | 92°25´34.14´´ | 14°59´14.64´´ |

| 3 | Ejido Santa Cecilia | 320 | 92°24´43.83´´ | 15°03´03.22´´ |

| 4 | Cantón La Estrella | 150 | 92°25´24.23´´ | 15°02´24.67´´ |

| 5 | Ejido Chamulapita | 540 | 92°25´51.91´´ | 15°00´43.05´´ |

| 6 | Cantón El Tivoli | 220 | 92°25´29.59´´ | 15°01´13.36´´ |

| 7 | Ejido Belisario Domínguez | 315 | 92°29´30.76´´ | 15°00´40.60´´ |

| 8 | Cantón El Caucho | 190 | 92°28´41.16´´ | 15°00´49.65´´ |

| 9 | Cantón El Cairo | 240 | 92°27´59.72´´ | 14°58´35.22´´ |

| 10 | Cantón Siria | 80 | 92°26´31.22´´ | 14°59´43.46´´ |

*UM = Sampling unit

Tree struture analysis

The tree species found in the sampling units were taxonomically identified, with common, scientific and family names, as described by Pennington and Sarukhán (2005).

Vertical stratification was defined by measuring the height of all the trees present in the sites, from the base of the stem to the apex. For this purpose, a Haga type altimeter was used (GmbH & Co D-90429, Germany).

The Importance Value Index (IVI), according to Curtis and McIntosh (1951), refers to the importance of one or several species in terms of the physical structure of a community or its species composition (Zarco-Espinosa et al., 2010) which reflects the percentage that each species has in the community.

The dominance, density and frequency values, as well as the value of importance per species, were obtained according to Stiling (1999).

The basimetric area of the trees (AB) was obtained by the following formula:

Where:

n = Number of trees

DAP = Diameter at breast height (DBH)

Density is defined as the number of individuals of a species that occupy a given area and is calculated as follows:

In order to know how the species are distributed, it is necessary to calculate the frequency, by counting the sampling units where they were found:

The frequency value can be interpreted as the probability of finding a species in any randomly chosen sampling unit of the same area. The relative frequency is calculated as follows:

The Shannon-Wiener Index measures the average degree of uncertainty to predict the species to which an individual randomly selected from the sampling units belongs (Somarriba, 1999).

The formula for the Shannon index is as follows:

Where:

H´ = Shannon-Wiener index

S= Number of species

Pi = Proportion of individuals of the i species

Ln = Natural logarithm

The Simpson Index measures the probability that two randomly selected individuals within a habitat belong to the same species (Pielou, 1969).

The formula to calculate the Simpson index is:

Where:

S = Number of species

N = Total of present organisms (or square units)

n = Number of samples per species

Information analysis

Based on the information obtained in the field, tables were created in Microsoft Office Excel ©2010 with the number of plant species found in each sampling unit, in which the averages were calculated for analysis and discussion for each site. The Shannon-Wiener and Simpson value indices were determined using the EstimateS program (Colwell, 2005), because it allows analyzing the number of plant species for a given sampling area.

The initial identification of the trees started from the common name directly in the field with the support and knowledge of the owners of the plots and the technician of the forestry consultancy. For the registration and taxonomic identification of the tree component, the work carried out by Pennington and Sarukhan (2005) and Miranda (2015) were taken as support. The taxonomic classification was made according to the APG III system.

Results and Discussion

Diversity of tree species

279 trees belonging to 23 species and 11 families of the medium evergreen forest were identified (Table 2).

Table 2 Tree species found in the agroforestry system of Coffea arabica L. in Soconusco, Chiapas.

| Common name |

Scientífic name | Family | Number of trees |

Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primavera | Tabebuia donnell smithii Rose | Bignoniaceae | 69 | 1 |

| Chalum | Inga micheliana Harms. | Fabaceae | 51 | 2 |

| Laurel | Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken | Boraginaceae | 34 | 1 |

| Cedro | Cedrela odorata L. | Meliaceae | 32 | 1 |

| Naranja | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Rutaceae | 20 | 2, 3 |

| Chiche | Aspidosperma megalocarpon Mull. Arg. | Apocynaceae | 12 | 1 |

| Aguacate | Persea americana Mill | Lauraceae | 9 | 2, 3 |

| Roble | Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | Bignoniaceae | 8 | 1 |

| Nance | Byrsonima crassifolia (L.) Kunth | Malpighiaceae | 7 | 2, 3 |

| Mango | Mangifera indica L. | Anacardiaceae | 6 | 2, 3 |

| Zapote | Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H. E. Moore & Stearn | Sapotaceae | 5 | 3 |

| Mandarina | Citrus reticulata Blanco | Rutaceae | 4 | 2, 3 |

| Marañón | Anacardium occidentale L. | Anacardiaceae | 3 | 3 |

| Caspirol | Inga laurina (Sw.) Willd. | Fabacea | 3 | 2, 3 |

| Guanacastle | Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. | Fabaceae | 3 | 1 |

| Paterno | Inga paterno Harms. | Fabaceae | 3 | 2, 3 |

| Yaite | Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth ex Walp. | Fabaceae | 2 | 2 |

| Coco | Cocos nucifera L. | Arecaceae | 2 | 3 |

| Casnicuil | Inga jinicuil Schltdl. Cham. | Fabaceae | 2 | 2, 3 |

| Chaperno | Lonchocarpus sp. | Fabacea | 1 | 2, 3 |

| Guagua | Inga sp. | Fabacea | 1 | 2, 3 |

| Palma | Acrocomia sp. | Arecaceae | 1 | 3 |

| Tamegüe | Tabebuia chrysantha (Jacq.) Nicholson | Bignoniaceae | 1 | 1 |

The most abundant species were Tabebuia donnell smithii Rose (maderable), Inga micheliana Harms. (firewood) Cordia alliodora (Ruiz et Pavón) Oken (posts) y Cedrela odorata L. (timber). As well as fruits such as Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck. (Orange), Byrsonima crassifolia) (L.) Kunth (Nance) and Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H. E .Moore & Stearn (Zapote). Cedrela odorata L, Brosimum alicastrum Sw., Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. and Tabebuia donnell smithii are typical of the semi-evergreen medium tropical forest (Villavicencio and Valdez, 2003).

The notable presence of Inga spp. in the region has been identified in other coffee growing regions of Mexico, such as in the Sierra Norte de Puebla where Martínez et al. (2007) determined that shade in coffee plantations was composed of a single species, such as Inga spp. (chalahuites), Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Kunth ex Walp. (cuacuite) or Alnus acuminata Kunth (elite).

The UM with the highest number of tree species (10) was number 4 (Cantón La Estrella). After this site, UM 5 (Ejido Chamulapita), UM 6 (Cantón El Tivoli) and UM 10 (Cantón Siria) followed with 9. In UM 9 (Cantón Cairo) there were four tree species and it was the site with the lowest number of species of this type. Of the total number of species found in the UMs, the largest number of timber and fruit trees was identified in the Cantón Siria (UM 10), with a total of 56. This site is located at a lower altitude.

On the other hand, in UM 8 (Cantón El Caucho), which is also at a low altitude with respect to the other eight sites, the least amount of timber and fruit trees was counted (13). This suggests the producer's preference for some species.

The difference in the number of species in the UMs may also be related to the age of the coffee plantations. The oldest plots registered an increase in the richness of trees in uses in relation to the youngest coffee plantations. In those older than 40 years, such as in UM 4 (Cantón La Estrella), there was an increase in the diversity of tree species. In addition to age, insulation can play a role; it is a community far from rural areas where tropical forests remains prevail.

Salvador-Morales et al. (2019) cite similar results, when studying agroforestry systems with Theobroma cacao L.; they found greater diversity and tree structure in T. cacao plantations over 40 years compared to younger plantations.

Of all the species found, most belong to the Fabaceae and Bignoniaceae families. These species are mainly used for firewood and timber.

Vertical stratification

The dominant height of the vegetation in the UMs was an average of 20 m, but specimens above 25 m were observed. Within the tree component, three strata were recognized. The upper stratum was considered to be trees with a height of 18 to 27 m, and in it, 19 individuals were identified, with dominance of Tabebuia donnell smithii (31.58 %). Aspidosperma megalocarpon Mull. Arg. trees represented 21.05 % and those of Inga laurina (Sw.) Willd. 15.79 % of the total number of trees.

In the middle stratum, an average height of 14 m was recorded in 167 individuals. The most common trees were Tabebuia donnell smithii (22.75 %), Inga micheliana (22.15 %), Cordia alliodora (17.36 %), Cedrela odorata (14.97 %) and Citrus sinensis (10.17 %). Finally, in the lower stratum with height less than 9 m, 93 trees were counted, 26.88 % of which were Tabebuia donnell smithii, 15.05 % to Inga micheliana, 9.67 % to Persea americana Mill and 7.52 % to Byrsonima crassifolia (L .) Kunth (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Vertical stratification of the tree component of the Coffea arabica L. agroforestry system in Soconusco, Chiapas.

The timber or fruit trees in the coffee production system exhibited greater height. This characteristic can be related to the producer's interest in subjecting them to cultural practices of pruning and thinning, in order to favor the entry of light to the coffee plant, and consequently, reduce or limit the growth of these shade trees. In these cases, in addition, species that are not important for the producer are eliminated and a decrease in diversity can be induced.

Importance Value Index (IVI)

The species with a high Importance Value Index (IVI) that exist in the UMs were: Inga micheliana, Tabebuia donnell smithii, Cedrela odorata, Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) Bertero ex A. DC. and Cordia alliodora. Inga micheliana was present at nine UMs. Other species with high IVI values were Citrus sinensis and Aspidosperma megalocarpon. Those that had structural importance in the UMs were Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H. E. Moore & Stearn and Persea americana (Table 3).

Table 3 Species with the highest Importance Value Index (IVI) in the Sampling Units (UM).

| Species | Relative dominance | Relative density | Relative frequency | IVI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UM 1 | 1 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 42.08 | 46.15 | 20.93 | 109.17 |

| 2 | Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken | 32.23 | 23.07 | 16.28 | 71.58 | |

| 3 | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | 9.76 | 11.54 | 13.95 | 35.25 | |

| 4 remaining species | 15.93 | 19.24 | 48.84 | 84.00 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 2 | 1 | Tabebuia donnell-smithii Rose | 34.45 | 34.62 | 19.44 | 88.51 |

| 2 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 32.72 | 19.22 | 25.00 | 76.95 | |

| 3 | Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken | 7.10 | 23.08 | 19.44 | 49.62 | |

| 2 remaining species | 25.73 | 23.08 | 36.12 | 84.92 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 3 | 1 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 24.00 | 26.09 | 21.95 | 72.03 |

| 2 | Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken | 28.19 | 21.74 | 17.07 | 67.01 | |

| 3 | Cedrela odorata L. | 13.08 | 8.70 | 21.95 | 43.73 | |

| 4 remaining species | 34.73 | 43.47 | 39.03 | 117.23 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 4 | 1 | Tabebuia rosea (Bertol.) DC. | 26.07 | 28 | 3.85 | 57.92 |

| 2 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 21.78 | 16 | 17.31 | 55.08 | |

| 3 | Tabebuia donnell-smithii Rose | 15.93 | 12 | 13.46 | 41.39 | |

| 7 remaining species | 36.22 | 44 | 65.38 | 145.61 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 5 | 1 | Persea americana Mill | 51.57 | 29.63 | 5.41 | 86.61 |

| 2 | Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) Oken | 16.64 | 33.33 | 18.92 | 68.89 | |

| 3 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 15.74 | 11.11 | 24.32 | 51.18 | |

| 6 remaining species | 16.05 | 25.93 | 51.35 | 93.32 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 6 | 1 | Tabebuia donnell-smithii Rose | 35.02 | 36 | 19.44 | 90.47 |

| 2 | Cedrela odorata L. | 13.63 | 16 | 25.00 | 54.63 | |

| 3 | Aspidosperma megalocarpon Mull. Arg. | 13.00 | 16 | 11.11 | 40.11 | |

| 6 remaining species | 38.35 | 32 | 44.45 | 114.79 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 7 | 1 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 15.16 | 24 | 20.45 | 59.62 |

| 2 | Cedrela odorata L. | 18.41 | 12 | 20.45 | 50.86 | |

| 3 | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | 19.20 | 16 | 13.64 | 48.83 | |

| 5 remaining species | 47.23 | 48 | 45.46 | 140.69 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 8 | 1 | Cedrela odorata L. | 59.61 | 38.50 | 31.03 | 129.11 |

| 2 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 23.72 | 38.50 | 31.03 | 93.21 | |

| 3 | Tabebuia donnell-smithii Rose | 3.97 | 7.70 | 24.14 | 35.80 | |

| 2 remaining species | 12.70 | 15.30 | 13.80 | 41.88 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 9 | 1 | Tabebuia donnell-smithii Rose | 83.60 | 69.70 | 31.82 | 185.12 |

| 2 | Inga micheliana Harms. | 13.40 | 24.30 | 40.91 | 78.55 | |

| 3 | Pouteria sapota (Jacq.) H. E. Moore & Stearn | 0.30 | 3.00 | 18.18 | 21.51 | |

| 1 remaining species | 2.70 | 3.00 | 9.09 | 14.82 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 | ||

| UM 10 | 1 | Tabebuia donell-smithii Rose | 24.23 | 37.50 | 16.28 | 78.01 |

| 2 | Cedrela odorata L. | 10.28 | 21.40 | 20.93 | 52.64 | |

| 3 | Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | 23.49 | 8.90 | 13.95 | 46.37 | |

| 6 remaining species | 42.00 | 32.20 | 48.84 | 122.98 | ||

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 |

In San Miguel, state of Veracruz, Villavicencio (2013) carried out the analysis of the tree structure of the coffee rustic agroforestry system, citing that Bursera simaruba (L.) Sarg. and Cordia alliodora reached the highest values of importance (IVI).

Even when the presence of species typical of the medium forest is evident, all the UMs showed an imbalance in their tree structure. Magdaleno et al. (2005), when evaluating the agroforestry system of trees in farmland in Vicente Guerrero, state of Tlaxcala, stated that the number of species that contribute 50 % or more of the IVI in each plot studied, varied from 9 to 13 in the low stratum, from 1 to 4 in the midium and from 1 to 3 in the high stratum.

Shannon-Wiener Index

The Shannon-Wiener index measures the average degree of uncertainty in predicting the species to which an individual taken at random from the UM belongs. The average value obtained in the coffee UMs of Soconusco was 1.2, which can be considered low in richness, when compared to those of other coffee regions in Mexico, such as the case of the Vicente Guerrero community (Magdaleno et al., 2005); thus, values from 3.55 to 3.89 were calculated. Other researchers obtained values of 3.5 in the Sierra de Atoyac, Veracruz (García-Mayoral et al., 2015). In the coffee region of Coatepec, Gómez-Martínez et al. (2018) registered an index of 8.3 in the traditional system; 2.94 in Tuxtla Chico, state of Chiapas and 2.71 in Tapachula, Chiapas (Roa-Romero et al., 2009). Zapata (2019), in a study carried out in agroforestry systems with coffee in three municipalities of Cundinamarca, Colombia, found that the tree species of greatest ecological importance in the AFS were Citrus sinensis, Calliandra pittieri Standl., Inga edulis Mart. and Cordia alliodora, and that it is related to the preferences of producers for these species due to favorable biophysical, environmental and/or economic interactions, by associating them with coffeé. In this study it was possible to appreciate that the producers have changed from the traditional shade species for timber tree species and fruit species and even introduced species, which at some point will bring them economic benefits.

Current results suggest increasing agronomic management in agroforestry systems associated with C. arabica through greater control of native vegetation with greater thinning to increase solar radiation for physiological purposes. Thus, it seeks to achieve increases in the yield of the coffee crop, in addition to reducing the effects of coffee rust; concomitantly, generate the possibility of increasing the density of coffee plants, and in other cases, that of some tree species of particular interest, which leads to a reduction in tree diversity.

Simpson Index

Simpson's index considers the dominance of the most representative species, that is, as the index increases, diversity decreases (Pielou, 1969). The predominant species in the coffee plantations are Inga micheliana and spring Tabebuia donnell smithii. The index value obtained in this study was 2.6. These species are widely accepted by producers. Inga micheliana (Chalum) for firewood and Tabebuia donnell smithii (Primavera) for the high commercial value of its wood.

Conclusions

The plantations of Coffea arabica with greater chronological age present greater diversity, tree structure and richness in uses with respect to the younger plantations.

The strata were categorized as lower (<9 m), middle (14 m), and upper (>18 m) strata, and the species with the greatest presence in the UMs were Tabebuia donnell smithii, Inga micheliana, Cordia alliodora and Cedrela odorata.

According to the Simpson and Shannon diversity indices, the prevailing vegetation has a low diversity of tree species. The highest Importance Value Index was presented in Inga micheliana and Tabebuia donnell smithii.

Acknowledgements

This work was accomplished thanks to the technical support provided by Despacho de Consultoría Forestal y Ambiental, S.C. (DECOFORES).

REFERENCES

Aguirre-Cadena, J. F., J. Cadena-Iñiguez, B. Ramírez-Velarde, B. I. Trejo-Téllez, J. P. Juárez-Sánchez y F. J. Morales-Flores. 2016. Diversificación de cultivos en fincas cafetaleras como estrategia de desarrollo. Caso de Amatlán. Acta Universitaria 26(1):30-38. Doi: 10.15174/au.2016.833. [ Links ]

Casanova-Lugo, F., L. Ramírez-Avilés, D. Parsons, A. Caamal-Maldonado, A. T. Piñeiro-Vázquez and V. Díaz-Echeverría. 2016. Environmental services from tropical agroforestry systems. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 22(3):269-284. Doi: 10.5154/r.rchscfa.2015.06.029. [ Links ]

Colwell, R. K. 2005. Estimaciones: estimación estadística de la riqueza de especies y especies compartidas a partir de muestras. Publicación de la aplicación y la guía del usuario de la versión 7.5. https://purl.oclc.org/estimates (21 de marzo del 2021). [ Links ]

Cox, W. G. 1981. Laboratory manual of general ecology. William C. Brown Co. Publishers. IA, USA. 230 p. [ Links ]

Curtis, H. and R. McIntosh. 1951. An upland forest continuum in the praire-forest border Region of Wisconsin. Ecology 32(3):476-496. Doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1931725. [ Links ]

Farfán, V. F. 2014. Agroforestería y Sistemas Agroforestales con Café. Centro Nacional de Investigaciones de Café-Cenicafé. Manizales, Caldas, Colombia. 343 p. [ Links ]

García, E. 1973. Modificaciones al sistema de clasificación climática de Köppen para adaptarlo a las condiciones de la República Mexicana. Instituto de Geografía de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México, D. F., México. 246 p. [ Links ]

García-Mayoral, L. E., J. I. Valdez-Hernández, M. Luna-Cavazos y R. López-Morgado. 2015. Estructura y diversidad arbórea en sistemas agroforestales de café en la Sierra de Atoyac, Veracruz. Madera y Bosques 21(3):69-82. Doi: 10.21829/myb.2015.213457. [ Links ]

Geissert, D., A. Mólgora-Tapia, S. Negrete-Yankelevich y R. Hunter M. 2017. Efecto del manejo de la cobertura vegetal sobre la erosión hídrica en cafetales de sombra. Agrociencia 51(2):119-133. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/agro/v51n2/1405-3195-agro-51-02-00119.pdf (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Gómez-Martínez, M. J., G. Díaz-Padilla, F. Charbonnier, G. Sánchez-Viveros y C. R. Cerdán-Cabrera. 2018. Ensambles arbóreos en sistemas agroforestales cafetaleros con diferente intensidad de manejo en Veracruz, México. Revista de Ciencias Ambientales 52(2):16-38. Doi: 10.15359/rca.52-2.2. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística (INEGI). 2005. Marco Geoestadístico Municipal, versión 3.1. Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. México. http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/mexicocifras/datos-geograficos/21/21158.pdf (1 de marzo del 2017). [ Links ]

Krishnamurthy, L. y M. Ávila. 1999. Agroforestería básica. PNUMA-FAO. Red de Información Ambiental para América Latina y el Caribe. México D. F., México. 340 p. [ Links ]

López, M., J. M. P. Vázquez, R. Martínez, y M. A. López. 2013. Rentabilidad de fincas de café. In: R. López M., G. Díaz P. y A. Zamarripa C. (Eds.). El sistema producto café en México: problemática y tecnología de producción. INIFAP-CIRGOC. Campo Experimental Cotaxtla. Cotaxtla, Ver., México. 462 p. [ Links ]

Magdaleno M., L., E. García M., J. I. Valdez-Hernández e V. de la Cruz I. 2005. Evaluación del sistema agroforestal "árboles en terrenos de cultivo", en Vicente Guerrero, Tlaxcala, México. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 28(3):203-212. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/610/61028304.pdf (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Martínez, M. A., V. Evangelista, F. Basurto, M. Mendoza y A. Cruz-Rivas. 2007. Flora útil de los cafetales en la Sierra Norte de Puebla, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, 78(1):15-40. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/rmbiodiv/v78n1/v78n1a3.pdf (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Miranda, F. 2015. La vegetación de Chiapas. Ed. Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas. Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chis., México. 686 p. [ Links ]

Moguel, P. y V. M. Toledo. 2004. Conservar produciendo: biodiversidad, café orgánico jardines productivos. Biodiversitas 55:2-7. http://200.12.166.51/janium/Documentos/4697.pdf (18 de abril de 2021). [ Links ]

Pielou, E. C. 1969. An Introduction to Mathematical Ecology. Wiley-Interscience. New York, NY, USA. 400 p. [ Links ]

Pennington, T. D. y J. Sarukhan. 2005. Árboles tropicales de México. Manual para la identificación de las principales especies. Ediciones Científicas Universitarias. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y Fondo de Cultura Económica. México, D. F., México. 523 p. [ Links ]

Pérez-Fernández, Y., M. V. González-Santiago, E. Escamilla-Robledo, A. Cruz-León, M. Rosas-Brugada y F. de J. Ruiz-Espinoza. 2016. Propuestas para la preservación de la vida en los cafetales en el municipio de Teocelo, Veracruz. Revista de Geografía Agrícola 57:7-16. Doi: 10.5154/r.rga.2016.57.007. [ Links ]

Pérez-Nieto, J., E. Valdés-Velarde y V. M. Ordaz-Chaparro. 2012. Cobertura vegetal y erosión del suelo en sistemas agroforestales de café bajo sombra. Terra Latinoamericana 30(3):249-259. h http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/tl/v30n3/2395-8030-tl-30-03-00249.pdf (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Reyes-Reyes, J. y J. López-Upton. 2003. Crecimiento del cedro rosado (Acrocarpus fraxinifolius Wight. & Arn.) a diferentes altitudes en fincas cafetaleras del Soconusco, Chiapas. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 9(2):137-142. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/629/62913142005.pdf (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Roa-Romero, H. A., M. G. Salgado-Mora y J. Álvarez-Herrera. 2009. Análisis de la estructura arbórea del sistema agroforestal de cacao (Theobroma cacao L.) en el Soconusco, Chiapas - México. Acta Biológica Colombiana 14(3):97-110. https://revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol/article/viewFile/12599/13199 (18 de abril de 2021). [ Links ]

Sáenz Reyes, J. T., J. A. González-Torres, J. Jiménez-Ochoa, A. Larios-Guzmán, M. Gallardo-Valdez, F. J. Villaseñor-Ramírez y C. Ibáñez-Reducindo. 2010. Alternativas agroforestales para reconversión de suelos forestales. Folleto Técnico Núm. 18. SAGARPA-INIFAP-CIRPAC. Campo Experimental Uruapan. Uruapan, Mich., México. 52 p. [ Links ]

Salgado-Mora, M. G., C. Ruiz-Bello, J. L. Moreno-Martínez, B. Irena-Martínez y J. F. Aguirre-Medina. 2018. Captura de carbono en biomasa aérea de árboles de sombra asociados a Coffea arabica L. en el Soconusco Chiapas. Agroproductividad 11(2):120-126. https://revista-agroproductividad.org/index.php/agroproductividad/article/view/136/114 (11 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Salvador-Morales, P., L. del C. Cámara-Cabrales, J. L. Martínez-Sánchez, R. Sánchez-Hernández y E. Valdés-Velarde. 2019. Diversidad, estructura y carbono de la vegetación arbórea en sistemas agroforestales de cacao. Madera y Bosques 25(1):1-14. Doi: 10.21829/myb.2019.2511638. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Gutiérrez, F., J. Pérez-Flores, J. J. Obrador-Olan, A. Sol S. y O. Ruiz-Rosado. 2016. Estructura arbórea del sistema agroforestal cacao en Cárdenas, Tabasco, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas, Pub. Esp. 14: 2695-2709. Doi: 10.29312/remexca.v0i14.439. [ Links ]

Somarriba, E. 1999. Diversidad Shannon. Agroforestería en las Américas 6(23):72-74. http://repositorio.bibliotecaorton.catie.ac.cr/handle/11554/7586 (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Somarriba, E. y J. Beer, J. 1999. Sistemas agroforestales con cacao en Costa Rica y Panamá. Agroforestería en las Américas 6(22):1-5. https://repositorio.catie.ac.cr/bitstream/handle/11554/6816/Sistemas_agroforestales_con_cacao_en_Costa_Rica_Panama.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Stiling, P. 1999. Ecology; Theories and Applications. 3rd edition. Prentice Hall. NJ, USA. 840 p. [ Links ]

Villavicencio-Enríquez, L. 2013. Caracterización agroforestal en sistemas de café tradicional y rústico, en San Miguel, Veracruz, México. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 19:67-80. Doi: 10.5154/r.rchscfa.2010.08.051. [ Links ]

Villavicencio-Enríquez, L. y J. I. Valdez-Hernández. 2003. Análisis de la estructura arbórea del sistema agroforestal rusticano de café en San Miguel, Veracruz, México. Agrociencia 37(4):413-423. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/302/30237410.pdf (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Zapata A., P. C. 2019. Composición y estructura del dosel de sombra en sistemas agroforestales con café de tres municipios de Cundinamarca, Colombia. Ciência Florestal 29(2):685-697. Doi: 10.5902/1980509827037. [ Links ]

Zarco-Espinosa, V. M., J. I. Valdez-Hernández, G. Ángeles-Pérez y O. Castillo-Acosta. 2010. Estructura y diversidad de la vegetación arbórea del Parque Estatal Agua Blanca, Macuspana, Tabasco. Universidad y Ciencia 26(1):1-17. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/uc/v26n1/v26n1a1.pdf (18 de abril del 2021). [ Links ]

Received: July 23, 2021; Accepted: March 30, 2022

texto em

texto em