Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.13 no.70 México mar./abr. 2022 Epub 09-Mayo-2022

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v13i70.1123

Scientific article

Structural characterization and carbon stored in a cold temperate forest surveyed in northwestern Mexico

1Programa de Doctorado en Ciencias con Orientación en Manejo de Recursos Naturales, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. México.

2Programa de Maestría en Agronegocios, Facultad de Ciencias Agrícolas y Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua. México.

3Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. México.

The objective of the present study was to define the diversity, composition, structure and content of carbon stored in the non-coeval tree mass of a research plot in northwestern Mexico. A census of the tree component was carried out in an area of 11.44 ha in the Aboreachi Ejido, Guachochi, Chihuahua. Each individual was labeled consecutively to record its normal diameter, total height and species. The Shannon-Wiener diversity index and Margalef’s richness index were estimated. The horizontal structure was characterized according to the importance value index. The Pretzsch index (A) was determined in order to evaluate the vertical structure. The total tree volume of each individual and its respective biomass were calculated using allometric equations. The aerial carbon content was determined by applying a biomass conversion factor of 0.5. The tree mass is made up of 16 species, belonging to six genera of five families. The species with the highest importance value index, of 55.93 %, was Pinus durangensis. Regarding the vertical structure, P. durangensis was the only species present in the three evaluated strata, in 49.86 % of the observations made. The species of the Pinus and Quercus genera are the ones that provide the largest volumes (155.53 m3 ha-1). A total of 93.22 Mg ha-1 of aerial biomass was calculated, of which P. durangensis represents 64.46 %; Pinus ayacahuite, 14.13 %, and Quercus sideroxyla, 12.33 %. The species with the highest carbon accumulation turned out to be P. durangensis, with a total of 30.04 Mg ha-1.

Key words Census of arboreal vegetation; Chihuahua; structure; diversity; Carbon stored; Pinus durangensis Ehren

El objetivo del presente estudio fue definir la diversidad, composición, estructura y contenido de carbono almacenado en la masa arbórea incoetánea de una parcela de investigación en el noroeste de México. Se realizó un censo del componente arbóreo en una superficie de 11.44 ha en el ejido Aboreachi, Guachochi, Chihuahua. Cada individuo se etiquetó de forma consecutiva; se registró el diámetro normal, altura total y especie. Se calculó el Índice de Diversidad de Shannon-Wiener y el Índice de Riqueza de Margalef. La estructura horizontal se caracterizó con el Índice de Valor de Importancia. Se determinó el índice de Pretzsch (A) para evaluar la estructura vertical. El volumen total árbol de cada individuo y su respectiva biomasa se obtuvo mediante ecuaciones alométricas; el contenido de carbono aéreo se determinó al aplicar un factor de conversión a la biomasa de 0.5. La masa arbórea está constituida por 16 especies, pertenecientes a seis géneros de cinco familias. Pinus durangensis presentó el mayor Índice de Valor de Importancia (55.93 %). Respecto a la estructura vertical, P. durangensis fue la única especie registrada en los tres estratos evaluados, con 49.86 % de las observaciones realizadas. Los taxones de Pinus y Quercus aportaron las mayores existencias de volumen (155.53 m3 ha-1). Se calculó un total de 93.22 Mg ha-1 de biomasa aérea; a P. durangensis correspondió 64.46 %, Pinus ayacahuite 14.13 % y Quercus sideroxyla 12.33 % del total. El taxón con más acumulación de carbono fue P. durangensis, con un total de 30.04 Mg ha-1.

Palabras clave Censo de vegetación arbórea; Chihuahua; estructura; diversidad; carbono almacenado; Pinus durangensis Ehren

Introduction

In principle, forest resources can be assessed using three methodologies: (1) temporary sites, (2) permanent sites (Corral-Rivas et al., 2008), and (3) permanent monitoring plots (Hernández and Reyna, 2015). It is also possible to use censuses (total records) in small stands (Aguirre et al., 1997). However, this methodology has the disadvantage of requiring more effort and time in large forest areas and is costly (Aguirre et al., 1995); in addition, the set of field activities to be carried out for data collection and registration of individuals is complicated, as some individuals may be overlooked or counted twice by mistake (Contreras et al., 1999).

In the state of Chihuahua, scientific monitoring of forests began in 1950 with the establishment of the first El Poleo Forestry Experimentation Site in Madera municipality (Estrada and Rodríguez, 2021). Individuals were identified and measured in 0.1 ha forestry monitoring plots which have been established in the same region since 1986 (Hernández-Salas et al., 2013). Permanent plots are intended for frequent monitoring of tree structures, with or without forestry treatment (Gadow et al., 1999; Martínez et al., 2019), in order to analyze and assess tree growth and stand performance (Rodríguez-Ortiz et al., 2011), observe the impact on biodiversity caused by climate change (Acosta-Mireles et al., 2014), and determine the functioning of the various components of the forest (Gutiérrez et al., 2015). However, there are no previous records of censuses in stands located in the interior of the state of Chihuahua oriented to monitor the dynamics of forest growth, structure and composition.

The characterization of the horizontal and vertical structure and the distribution of the different forest species that make up a forest are important to understand its functioning as a forest ecosystem, since the results derived from these data serve as a basis for making informed decisions for its proper management (Corral et al., 2005; Gadow et al., 2012; Graciano-Ávila et al., 2017; García et al., 2019).

The estimation of the stand volume is a basic tool for forest inventories (Corral-Rivas and Navar-Cháidez, 2009). It is also an indicator of the productive potential of a stand for planning, executing and evaluating the activities proposed within forest management programs (Magaña et al., 2008). Additionally, with such determinations it is possible to know the ecological potential of forest ecosystems as a main source of biomass generation and carbon storage through the accumulation of organic matter (Ni et al., 2016).

The establishment of permanent plots in large forest areas for the purpose of carrying out periodic monitoring of the diversity, composition, structure and study of the carbon reservoirs serves as a basis for the development of plans for research, conservation, management, and sustainable use of timber forest resources. Within this context, the objective of the present work was to determine the diversity, composition, structure and content of carbon stored in the non-coeval tree mass of a permanent research plot, using census information of northwestern Mexico.

Materials and Methods

Location of the study area

The study was conducted in the Aboreachi forest ejido, located in the municipality of Guachochi, southwest of the state of Chihuahua, Mexico, in the physiographic province of the Western Sierra Madre, whose coordinates are 27°11'46"N 107°23'13"W (Figure 1). The area corresponds to a non-even-aged cold temperate forest with diverse forest species; the soil types are Eutric Cambisol, EutricPlanosol and Eutric Regosol of medium to fine texture (INEGI, 2014). The climate is C(E)(w2)(x'), which corresponds to a semi-cold humid climate, with a mean annual temperature of 5 to 12 °C and a mean annual precipitation of 621.3 mm (INEGI, 2008).

Sampling method

The study area comprised an area of 11.44 ha, last intervened in 1992; in 2017 it was established as a Permanent Forest Research Plot (PFRP). The dasometric information was obtained by census or total registration in the summer of 2018. The database consisted of 5 092 trees, whose normal diameter (DN) was measured at a height of 1.3 m from ground level with a Forestry Suppliers Inc® five-meter diameter tape, and the total height (H), with a Suunto® PM5-1520 hypsometer. The species to which each individual belonged was also recorded.

Data analysis

In order to determine the alpha diversity, the Shannon-Wiener index was calculated using the expression described by Shannon (1948) (Equation 1):

Where:

H’ = Shannon-Wiener Index

S = Number of species

p i = Proportion of individuals of species i with respect to the total number of individuals

N = Total number of individuals

n i = Number of individuals of species i

Equation 2 was used to measure the species richness with the Margalef index (Margalef, 1972):

Where:

D Mg = Margalef's Index

S = Number of species

nl = Natural logarithm

N = Total number of individuals

The horizontal structure of the stand was determined by characterizing the distribution of the diameter classes present, and the number of individuals for each taxon was quantified. Abundance was calculated based on the number of trees per species, and dominance, based on the basal area. Since a census was carried out, it was not necessary to evaluate the frequency of the species. The Importance Value Index was estimated according to the above indicators (IVI) (Equation 3), with the average percentage from 0 to 100 of the previous ecological indicators (Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2011):

Where:

IVI = Importance Value Index

RA i = Relative abundance

RD i = Relative density

The characterization of the vertical structure of the stand was carried out with the Vertical Species Distribution Index (A) (Pretzsch, 2009) by means of Equations 4, 5 and 6. According to Jiménez et al. (2001), this index defines three height zones: Zone I covers 80 % to 100 % of the maximum tree height; Zone II, 50 to 80 %, and Zone III, 0 to 50 %. This index is used to determine the structural diversity in terms of vertical distribution of species (Alanís-Rodríguez et al., 2020); García et al. (2020) point out that A max corresponds to the maximum value for each of the species per stratum; finally, A rel is the standardization of A:

Where:

A = Index of vertical distribution of species

A max = Maximum value per species in each stratum

A rel = Standardized value of A

S= Number of species present

Z= Number of height strata

P ij = Percentage of species in each zone

nl = Natural logarithm

N = Total number of individuals

Table 1 shows the equations used to estimate the total tree volume (volume of stump, trunk and branches) of each individual of the recorded species; the expressions are based on the Shumacher-Hall model, collected from the biometric study of the Aboreachi ejido and from the study by Graciano-Ávila et al. (2019). Subsequently, the results per individual were used to estimate the total tree volume per hectare and at the PFRP level.

Table 1 Equations utilized to estimate the total tree volume at individual level for the coniferous and broad-leaved species present in the study area.

| Species | Equation |

|---|---|

| Pinus durangensis Ehren. |

|

| Pinus ayacahuite Ehren. |

|

| Pinus chihuahuana Engelm.** |

|

| Pinus arizonica Engelm. |

|

| Pinus leiophylla Schltdl. & Cham. |

|

| Pinus engelmannii Carr. |

|

| Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald* |

|

| Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl. |

|

| Quercus rugosa Née |

|

| Quercus mcvaughii Bonpl.† |

|

| Quercus candicans Née† |

|

| Quercus fulva Liebm.† |

|

| Arbutus xalapensis Kunth˟ |

|

| Arbutus bicolor González˟ |

|

| Juniperus deppeana Steud. |

|

| Alnus spp. Kunth |

|

* Corresponding to the equation for Pinus leiophylla; †the equation for Quercus spp.; ˟the equation for Arbustus spp.; V = Volume (m3); ND = Normal diameter (cm); H = Total height (m).

According to Aguirre-Calderón and Jiménez-Pérez (2011), the estimation of biomass and carbon content can be derived from equations based on the normal diameter at the individual tree level. Therefore, the allometric models shown in Table 2 were used to estimate the aboveground biomass per individual of the species recorded. The biomass of each individual was then scaled to the level of taxon, genus and family, which allowed calculations to be made in Megagrams per hectare, and, therefore, at the level of the entire PFRP. The carbon content was obtained by multiplying the biomass value by the conversion factor 0.50 suggested by the IPCC (1996); the unit of measurement utilized to express the results for the biomass and carbon stored in the tree layer per unit area was the Megagram per hectare (Mg ha-1).

Table 2 Equations for estimating the biomass of coniferous and broad- leaved species.

| Species | Allometric equation | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Pinus durangensis Ehren. |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2010) |

| Pinus ayacahuite Ehren. |

|

Rojas-García et al. (2015) |

| Pinus chihuahuana Engelm.* |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2009) |

| Pinus arizonica Engelm. |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2010) |

| Pinus leiophylla Schltdl. & Cham. |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2009) |

| Pinus engelmannii Carr. |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2009) |

| Pinus lumholtzii .L. Rob. & Fernald * |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2009) |

| Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl. |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2009) |

| Quercus rugosa Née |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2009) |

| Quercus mcvaughii Bonpl.† |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2010) |

| Quercus candicans Née† |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2010) |

| Quercus fulva Liebm.† |

|

Návar-Cháidez (2010) |

| Arbutus xalapensis Kunth |

|

Aguilar-Hernández et al. (2016) |

| Arbutus bicolor González• |

|

Aguilar-Hernández et al. (2016) |

| Juniperus deppeana Steud˟ |

|

Rodríguez-Laguna et al. (2007) |

| Alnus spp. Kunth | e |

Acosta-Mireles et al. (2002) |

*Corresponding to the equation for Pinus leiophylla; †equation for Quercus spp.; •equation for Arbutus xalapensis; ˟equation for Juniperus flaccida; B = Biomass (kg); ND = Normal diameter (cm); exp = Coefficient e (natural logarithm base).

Results and Discussion

Floristic diversity

Sixteen tree species belonging to six genera of the families Pinaceae, Fagaceae, Cupressaceae, Ericacea, and Betulaceae were registered in the PFRP; this composition of families was higher than those cited by García et al. (2020) and Hernández-Salas et al. (2013) in coniferous forests of the state of Chihuahua. The most representative family was Pinaceae, with seven species; this result is similar to the one documented by Márquez et al. (1999), who registered eight Pinaceae of the genus Pinus in a forest in Durango, followed by Fagaceae, Cupressaceae, Ericacea and Betulaceae, with five taxa, one, two and one, respectively. González-Elizondo et al. (2012) and Silva-Flores et al. (2014) indicate that these families are representative of the temperate forests of the Western Sierra Madre.

Species diversity and richness

The Shannon-Wiener Index (H') normally ranges between 1 and 5. Values above 3.5 are considered as high diversity; 2 to 3.5, as medium diversity, and less than 2, as low diversity (Margalef, 1972). A value of 1.52 was estimated for the PFRP, which is higher than the value estimated by Solís et al. (2006), of 1.21. For their part, Delgado et al. (2016), reported a maximum value of 1.58; in an analysis of altitudinal diversity in pine-oak forests of Durango, Medrano et al. (2017) estimated a minimum value of 1.94, which is higher than the value determined in the study documented herein. As a consequence of the physiographic and climatic conditions, the PFRP has a low species diversity, typical of temperate forest ecosystems that have been harvested in the medium term, with typical second-growth or regenerating stands.

Margalef’s richness index (D Mg ) corresponds to a value of zero when there is only one taxon in the stratum, but it can approach 5 if the number of existing species increases the complexity of the ecosystem. The study area exhibited a value of 1.76, which is lower than the value obtained by Domínguez et al. (2018) of 1.79 for mixed coniferous forests in the region of Pueblo Nuevo, Durango; for their part, García et al. (2020) estimated a value of 1.52 in mixed forests in the state of Chihuahua, lower than that reached in the PFRP; however, the values correspond to a wealth of species similar to that described in the present study. This result is consistent with what has been cited in other research for temperate ecosystems, as the climatic and physiographic conditions of coniferous forests and pine-oak associations limit the development of a wide variety of tree taxa; the opposite is the case in tropical regions, where it is possible to observe more complex tree associations.

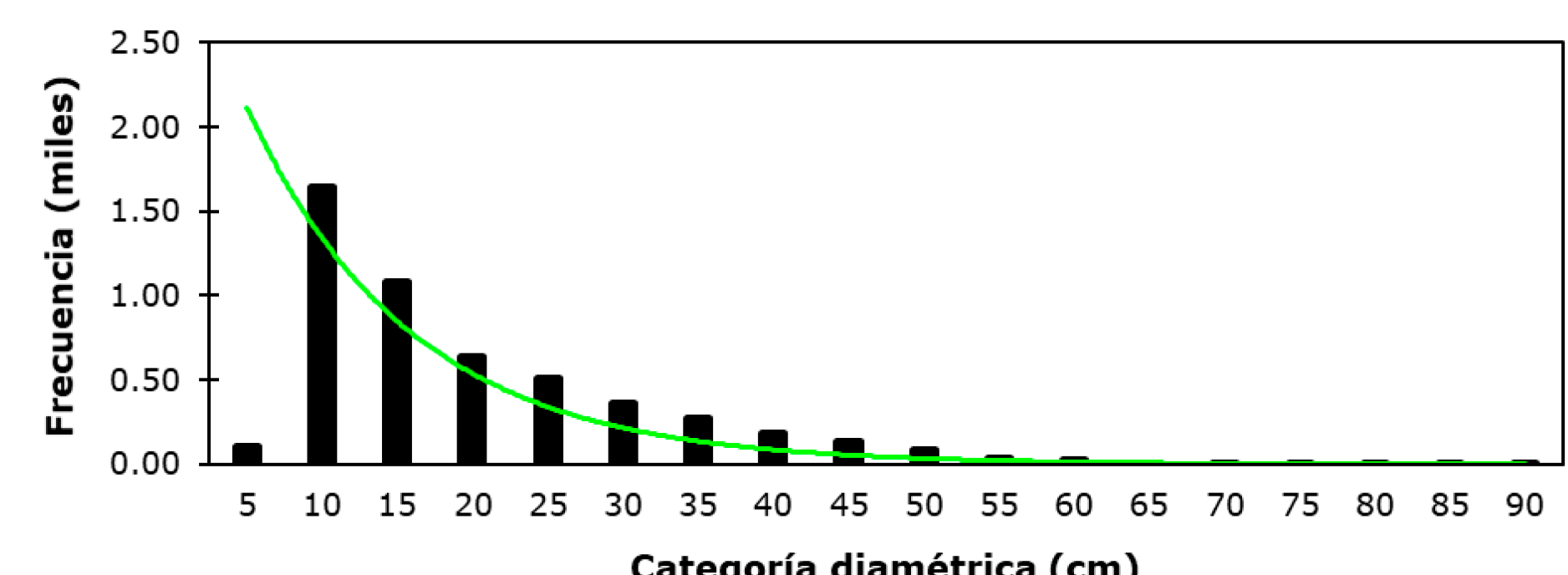

Horizontal structure

The horizontal structure of the tree stands in the PFRP showed an irregular distribution that is typical of a second-growth forest or stands in the process of regeneration, due to previous timber harvests, anthropogenic impacts such as land use change, fire, or environmental impact in the form of pests and diseases. The highest frequency was registered in trees with a diameter category of 10 cm, decreasing in proportion to larger diameters (Figure 2). In the PFRP, an average normal diameter of 16.72 cm was obtained for the total number of species recorded. The Pinus genus presented an average diameter of 19.21 cm and Quercus 13.88 cm; values similar to those reported by Návar-Cháidez and González-Elizondo, (2009), as well as by Delgado et al. (2016), for pine-oak forests in Durango, and by García et al. (2019) in pine-oak forests of the southern part of the state of Chihuahua.

Frecuencia (miles) = Frequency (thousands); Categoría diamétrica = Diameter class.

Figure 2 Frequency of tree species by diameter class determined in the PFRP.

The commercial tree community that makes up the PFRP consists of 5 092 registered individuals, equivalent to 445 trees per hectare (trees ha-1) (Table 3). Pinus had the highest density, with a total of 3 769 trees (329 trees ha-1) representing 74.02 % of the total plot; the second place is occupied by the Quercus genus, with 1 062 specimens (93 trees ha-1), amounting to 20.86 % of the stock. The Juniperus genus was present with 132 individuals (12 arb ha-1), equivalent to 2.60 % of the total. Finally, the "other leaves" group accounted for 129 trees (11 trees ha-1), which represented 2.52 % of the total number of individuals in the area. The Pinus and Quercus genera add up to 94.87 % of the tree cover; their values coincide with those described by Delgado et al. (2016), Domínguez et al. (2018), and García et al. (2019) in forests of the states of Durango and Chihuahua.

Table 3 Species and basic statistics of the trees present in the experimental plot.

| Family | Species | N | Diameter (cm) | Height (m) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Max | Medium | Min | DS | Max | Medium | Min | DS | |||

| Pinacea | Pinus durangensis Ehren. | 2 539 | 86.20 | 22.55 | 5.00 | 12.90 | 29.30 | 10.67 | 3.00 | 4.48 |

| Pinus ayacahuite Ehren. | 885 | 51.80 | 17.00 | 4.00 | 8.33 | 23.20 | 8.83 | 2.80 | 3.59 | |

| Pinus chihuahuana Engelm | 321 | 49.40 | 19.81 | 6.00 | 9.04 | 20.10 | 8.98 | 3.00 | 3.44 | |

| Pinus arizonica Engelm | 11 | 44.80 | 18.85 | 7.70 | 12.63 | 17.80 | 8.95 | 4.00 | 4.56 | |

| Pinus leiophylla Schltdl. & Cham. | 6 | 37.60 | 19.62 | 7.90 | 10.96 | 13.50 | 7.77 | 5.30 | 3.19 | |

| Pinus engelmannii Carr. | 5 | 36.00 | 16.26 | 7.80 | 11.74 | 17.00 | 8.98 | 6.00 | 4.77 | |

| Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald | 2 | 32.00 | 20.35 | 8.70 | 16.48 | 16.40 | 10.70 | 5.00 | 8.06 | |

| Fagaceae | Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl. | 845 | 90.00 | 17.84 | 6.30 | 11.19 | 19.20 | 7.57 | 2.70 | 3.05 |

| Quercus rugosa Née | 111 | 53.10 | 13.27 | 6.50 | 6.86 | 12.60 | 6.24 | 2.90 | 1.77 | |

| Quercus mcvaughii Bonpl. | 104 | 61.90 | 14.48 | 7.00 | 8.16 | 17.20 | 6.50 | 3.00 | 2.09 | |

| Quercus candicans Née | 1 | - | 7.80 | - | - | - | 4.90 | - | - | |

| Quercus fulva Liebm. | 1 | - | 16.00 | - | - | - | 7.00 | - | - | |

| Ericacea | Arbutus xalapensis Kunth | 102 | 44.10 | 17.34 | 5.90 | 7.71 | 16.10 | 6.10 | 3.00 | 2.17 |

| Arbutus bicolor González | 22 | 37.50 | 18.47 | 8.20 | 7.26 | 13.00 | 6.20 | 3.10 | 2.53 | |

| Cupressaceae | Juniperus deppeana Steud. | 132 | 45.00 | 12.15 | 6.80 | 6.60 | 12.40 | 4.91 | 2.60 | 1.73 |

| Betulaceae | Alnus spp. Kunth | 5 | 26.30 | 15.70 | 10.70 | 6.43 | 10.00 | 8.02 | 5.60 | 1.94 |

| Overall average | 5 092 | 49.69 | 16.72 | 7.04 | 11.63 | 16.99 | 7.65 | 3.71 | 4.19 | |

N = Number of observations; Max = Maximum; Min = Minimum; SD = Standard deviation.

The species with the highest abundance was Pinus durangensis Ehren., with 2 539 individuals (222 trees ha-1), equivalent to 49.86 % of the total tree cover; P. ayacahuite Ehren. registered 885 trees (77 trees ha-1), with 17.38 % of the total, and Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl., 845 individuals (74 trees ha-1), which amount to 16.59 % of the total. These three species together constitute 83.83 % of the existing trees within the PFRP (Table 4). Zúñiga et al. (2018) obtained similar results in the region of Pueblo Nuevo, Durango; according to these authors, P. durangensis tends to be the most representative taxon in pine-oak forests.

Table 4 Estimated structural parameters for the species recorded in the experimental plot under analysis.

| Species | Abundance | Dominance | IVI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute N |

Relative % |

Absolute (m2) |

Relative % |

||

| Pinus durangensis Ehren. | 2 539 | 49.86 | 134.62 | 62.00 | 55.93 |

| Pinus ayacahuite Ehren. | 885 | 17.38 | 24.92 | 11.48 | 14.43 |

| Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl. | 845 | 16.59 | 29.41 | 13.54 | 15.07 |

| Pinus chihuahuana Engelm. | 321 | 6.30 | 11.93 | 5.50 | 5.90 |

| Juniperus deppeana Steud. | 132 | 2.59 | 1.98 | 0.91 | 1.75 |

| Quercus rugosa Née | 111 | 2.18 | 7.43 | 3.42 | 2.80 |

| Arbutus xalapensis Kunth | 102 | 2.00 | 2.88 | 1.33 | 1.66 |

| Quercus mcvaughii Bonpl. | 104 | 2.04 | 2.25 | 1.04 | 1.54 |

| Arbutus bicolor González | 22 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.31 | 0.37 |

| Pinus arizonica Engelm. | 11 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.21 |

| Pinus leiophylla Schltdl. & Cham. | 6 | 0.12 | 0.23 | 0.11 | 0.11 |

| Pinus engelmannii Carr. | 5 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.08 |

| Alnus spp. Kunth. | 5 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.07 |

| Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald | 2 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Quercus candicans Née | 1 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Quercus fulva Liebm. | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Total | 5 092 | 100.00 | 217.13 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

N = Number of observations; IVI = Importance value index.

The largest basal area corresponded to P. durangensis, with 134.62 m2, equivalent to 11.77 m2 ha-1; Q. sideroxyla, with 29.41 m2 (2.57 m2 ha-1); P. ayacahuite, with 24.92 m2 (2.18 m2 ha-1), and P. chihuahuana Engelm., with 11.93 m2 (1.04 m2 ha-1). Together, these three taxa totaled 200.88 m2 (17.56 m2 ha-1), i.e., 92.52 % of the total. Valenzuela and Granados (2009) point out that P. durangensis is found in two tree associations in the state of Durango; Graciano-Ávila et al. (2020) report that P. durangensis and Q. sideroxyla are the most dominant species in a forest of the same state.

At the PFRP, Pinus exhibited an IVI of 76.70 %, while the genus with the lowest value was Alnus, with 0.07 % of total. According to López-Hernández et al. (2017), in pine-oak forests of the state of Puebla, Pinus spp. tends to be the most representative, with up to 85.20 % of the total. P. durangensis, Q. sideroxyla, P. ayacahuite, and P. chihuahuana were the species with the highest IVI: 55.93, 15.07, 14.43, and 5.90 %, respectively; these four taxa together accounted for 91.33 % of the total. Eight species were registered with values of less than one percent; in this regard, Q. candicans Née and Q. fulva Liebm. were the least outstanding. According to Graciano-Ávila et al. (2017), in a forest of Durango, P. durangensis Q. sideroxyla, and P. teocote Schiede ex Schltdl. were the most prevalent species, with 62.43 % of the community's total.

Vertical structure

The PFRP exhibited a value of 1.8916 in the vertical distribution index of species, with an A max of 3.8712 and an A rel of 48.86 %. García et al. (2020) determined an A index of 2.58, an A max of 3.40, and an A rel of 75.56 % in the mature tree stratum of a mixed forest in Chihuahua; on their part, Graciano-Ávila et al. (2020) calculated a maximum value for A of 2.72, with an A max of 3.87 and an A rel of 70 % in managed forests of Durango.

The distribution of individuals by stratum obtained from the analysis may be a consequence of the effect of the previous application of silvicultural treatments to this irregular stand, where the aim was to take advantage of the over mature individuals that were mainly located in the high stratum (I), so that the opening of the canopy favored natural regeneration, increasing the number of individuals and species in the low stratum (III). In the distribution of strata (Table 5), P. durangensis was observed to be the only species present in stratum I, with a maximum height of 29.30 m; stratum II was represented by 10 tree species, among which, again, P. durangensis registered the highest proportion within the stratum, with 80.77 %, followed by P. ayacahuite with 10.06 %. The height range for this stratum was 14.70 to 23.43 m. Finally, stratum III presented 100 % of the registered taxa, among which P. durangensis was the most abundant, representing 44.99 % of the total number of individuals in the stratum and 38.92 % of the individuals in the entire area, followed by P. ayacahuite and Q. sideroxyla, which amount to 16.04 and 15.99 %, respectively, of the total tree inventory of the PFRP.

Table 5 Pretzch’s vertical index values determined for the tree stratum of the research plot.

| Stratum | Height (m) | N | Proportion (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Of the stratum | Of the PFRP | |||

| High (I) | (23.44 - 29.30) | |||

| Pinus durangensis Ehren. | 11 | 100.00 | 0.22 | |

| Subtotal | 11 | 100.00 | 0.22 | |

| Medium (II) | (14.70 - 23.43) | |||

| Pinus durangensis Ehren. | 546 | 80.77 | 10.72 | |

| Pinus ayacahuite Ehren. | 68 | 10.06 | 1.34 | |

| Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl. | 31 | 4.59 | 0.61 | |

| Pinus chihuahuana Egelm. | 26 | 3.85 | 0.51 | |

| Arbutus xalapensis Kunth | 1 | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

| Quercus mcvaughii Bonpl. | 1 | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

| Pinus arizonica Engelm. | 1 | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

| Pinus engelmannii Carr. | 1 | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

| Pinus lumholtzii B. L. Rob. & Fernald | 1 | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

| Subtotal | 676 | 100.00 | 13.28 | |

| Low (III) | (2.60 - 14.69) | |||

| Pinus durangensis Ehren. | 1 982 | 44.99 | 38.92 | |

| Pinus ayacahuite Ehren. | 817 | 18.55 | 16.04 | |

| Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl. | 814 | 18.48 | 15.99 | |

| Pinus chihuahuana Engelm. | 295 | 6.70 | 5.79 | |

| Juniperus deppeana Steud. | 132 | 3.00 | 2.59 | |

| Quercus rugosa Née | 111 | 2.52 | 2.18 | |

| Arbutus xalapensis Kunth | 101 | 2.29 | 1.98 | |

| Quercus mcvaughii Bonpl. | 103 | 2.34 | 2.02 | |

| Arbutus bicolor González | 22 | 0.50 | 0.43 | |

| Pinus arizonica Engelm. | 10 | 0.23 | 0.20 | |

| Pinus leiophylla Schltdl. & Cham. | 6 | 0.14 | 0.12 | |

| Pinus engelmannii Carr. | 4 | 0.09 | 0.08 | |

| Alnus spp. Kunth. | 5 | 0.11 | 0.10 | |

| Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Quercus candicans Née | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Quercus fulva Liebm. | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | |

| Subtotal | 4 405 | 100.00 | 86.51 | |

| Total | 5 092 | 300.00 | 100.00 | |

N = Number of observations.

The vertical distribution analysis showed that species diversity decreases as the tree height increases; similar results were described by García et al. in mixed forests in 2019, and in a forest of Pseudotsuga in 2020, in both cases in the south of the state of Chihuahua.

Estimation of total tree volume, aboveground biomass and carbon stocks

A total tree volume of 1 810.38 m3 was quantified in the PFRP (Table 6). The genus Pinus contributed the largest volume, with 1 545.69 m3 equivalent to 85.37 % of the total; for the Quercus genus, a volume of 233.63 m3 was estimated, which corresponded to 12.90 % of the total. At the species level, a volume of 1 222.62 m3 (67.53 %) was calculated for P. durangensis, followed by P. ayacahuite, with 216.11 (11.93 %) and Q. sideroxyla, with 208.44 m3 (11.51 %). In terms of total volume at the hectare level, the PFRP exhibited an average volume of 158.25 m3 ha-1, which is lower than that obtained by Graciano-Ávila et al. (2019) in temperate forests of Durango, of 207.36 m3 ha-1; the volumetric difference is due to the fact that the study carried out in the El Salto area shows a greater density with a higher average diameter and height than those registered in this study.

Table 6 Volume, biomass and aboveground carbon obtained in the species registered in the research plot.

| Species | N | TVT (m3) | B (Mg) | C (Mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pinus durangensis Ehren. | 2 539 | 1 222.62 | 687.45 | 343.73 |

| Pinus ayacahuite Ehren. | 885 | 216.12 | 150.74 | 75.37 |

| Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl. | 845 | 208.44 | 131.46 | 65.73 |

| Pinus chihuahuana Engelm. | 321 | 101.70 | 63.03 | 31.51 |

| Juniperus deppeana Steud. | 132 | 9.34 | 7.02 | 2.82 |

| Quercus rugosa Née | 111 | 12.34 | 3.64 | 1.82 |

| Arbutus xalapensis Kunth | 102 | 14.65 | 5.33 | 2.66 |

| Quercus mcvaughii Bonpl. | 104 | 12.75 | 12.22 | 6.11 |

| Arbutus bicolor González | 22 | 3.36 | 1.25 | 0.71 |

| Pinus arizonica Engelm. | 11 | 4.31 | 1.95 | 0.97 |

| Pinus leiophylla Schltdl. & Cham. | 6 | 1.55 | 1.22 | 0.61 |

| Pinus engelmannii Carr. | 5 | 1.57 | 0.23 | 0.11 |

| Alnus spp. Kunth | 5 | 0.56 | 0.32 | 0.16 |

| Pinus lumholtzii B.L. Rob. & Fernald | 2 | 0.93 | 0.47 | 0.23 |

| Quercus candicans Née | 1 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Quercus fulva Liebm. | 1 | 0.10 | 0.09 | 0.05 |

| Total | 5 092 | 1 810.38 | 1 066.44 | 532.61 |

N = Number of observations; TVT = Total volume of the tree; B = Biomass; C = Carbon.

Regarding the aerial tree biomass determined in the PFRP, a total of 1 066.44 Mg was calculated, of which P. durangensis registered 687.45 Mg (64.46 %), P. ayacahuite 150.74 Mg (14.13 %), and Q. sideroxyla 131.46 Mg (12.33 %) of the total; Q. candicans had the lowest biomass value, with 0.01 Mg. The estimated biomass at the hectare level was 93.22 Mg, which is within the biomass range of 75.43 to 176.06 Mg determined by Martínez et al. (2016) ha-1 for pine-oak forests in the state of Durango.

The volume, biomass and above-ground carbon obtained in the species recorded in the research plot (30 to 45 cm) exhibited values of 60.62, 67.46, 63.42 and 64.99 Mg, respectively; these concentrated 47.99 % of the total carbon in the PFRP (Figure 3). The carbon stored by the genus Pinus was the highest (452.55 Mg), amounting to 84.68 % of the total PFRP; Quercus accumulated 73.71 Mg, which represents 13.79 % of the total stored.

Frecuencia (miles)= Frequency (thousands); Categoría diamétrica = Diameter class; Carbono = Carbon.

Figure 3 Aerial carbon stored by diameter class in the research plot.

Of the existing species in the study plot (11.44 ha), P. durangensis had the highest accumulated carbon values (343.72 Mg), followed by P. ayacahuite (75.37 Mg) and Q. sideroxyla (65.73 Mg). These three species accounted for 90.72 % of the total carbon accumulated in that plot. The mean value of this parameter was 46.71 Mg ha-1; the results are in agreement with those reported by Graciano-Ávila et al. (2019) in pine-oak forests of the state of Durango (65.14 Mg ha-1), but are lower than those published by Buendía-Rodríguez et al. (2019), in the range of 58.36 to 123.49 Mg ha-1, for pine-oak associations in southern part of the state of Nuevo León.

Studies characterizing forest stands in terms of diversity, structure, volume, biomass and carbon content of the tree stratum, based on census information regarding large areas such as the one documented herein, will help managers to plan informed and oriented actions in order to achieve sustainable management of timber resources in northwestern Mexico. In addition, periodic monitoring of large permanent plots will reveal the dynamics of growth over time and, thus, contribute to the development of research programs for the use and conservation of forest resources.

Conclusions

The Permanent Forestry Research Plot in the Aboreachi ejido has a richness of tree species similar to that observed in other regions of the Western Sierra Madre. The Pinaceae family is the most representative, with seven species present, followed by the Fagaceae, with five taxa. The species with the highest Importance Value Index are P. durangensis, with 55.93 % of the total, and Q. sideroxyla, with 15.07 %. In the vertical structure of the stand, P. durangensis is the only species present in the three profiles evaluated, occupying 49.86 % of the records, followed by P. ayacahuite, with 17.38 % of the total.

Species of the Pinaceae and Fagaceae families have the largest heights and diameters; both contribute the greatest stock of volume, biomass and stored aerial carbon. A total tree volume of 1 810.38 m3 has been estimated; Pinus and Quercus contribute 85.37 % and 12.90 %, respectively, of the total. The total aboveground biomass is 1 066.44 Mg, of which P. durangensis contributes 64.46 % of the total; P. ayacahuite, 14.13 %, and Q. sideroxyla, 12.33 %. The species with the highest carbon accumulation is P. durangensis, with a total of 343.72 Mg.

Referencias

Acosta-Mireles, M., J. Vargas-Hernández, A. Velázquez-Martínez y J. D. Etchevers-Barra. 2002. Estimación de la biomasa aérea mediante el uso de relaciones alométricas en seis especies arbóreas en Oaxaca, México. Agrociencia 36(6):725-736. https://agrociencia-colpos.mx/index.php/agrociencia/article/view/225/225 (12 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Acosta-Mireles, M., F. Carrillo-Anzures, D. Delgado y E. Velasco Bautista. 2014. Establecimiento de parcelas permanentes para evaluar impactos del cambio climático en el Parque Nacional Izta-Popo. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 5(26):6-29. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v5i26.287. [ Links ]

Aguilar-Hernández L., R. García-Martínez, A. Gómez-Miraflor y O. Martínez-Gómez. 2016. Estimación de biomasa mediante la generación de una ecuación alométrica para madroño (Arbutus xalapensis). In: IV Congreso Internacional y XVIII Congreso Nacional de Ciencias Agronómicas. Chapingo, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 529-530. [ Links ]

Aguirre-Calderón, O. A. y J. Jiménez-Pérez. 2011. Evaluación del contenido de carbono en bosques del sur de Nuevo León. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2(6):73-84. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v2i6.575. [ Links ]

Aguirre, O. A., J. Jiménez y B. Meráz. 1995. Optimización de inventarios para manejo forestal: Un caso de estudio en Durango, México. Investigación Agraria: Sistemas y Recursos Forestales 4(1):107-118. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/IA/article/view/4854 (7 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Aguirre, O. A., J. Jiménez, E. Treviño y B. Meráz. 1997. Evaluación de diversos tamaños de sitio demuestreo en inventarios forestales. Madera y Bosques 3(1):71-79. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.1997.311380. [ Links ]

Alanís-Rodríguez, E., J. Jiménez-Pérez, A. Valdecantos-Dema, M. Pando-Moreno, O. A. Aguirre-Calderón y E. J. Treviño-Garza. 2011. Caracterización de la regeneración leñosa post-incendio de un ecosistema templado del parque ecológico Chipinque, México. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 17(1):31-39. Doi: https://doi.org/10.5154/r.rchscfa.2010.05032. [ Links ]

Alanís-Rodríguez, E., E. A. Rubio-Camacho, P. A. Canizales-Velázquez, A. Mora-Olivo, M. Á. Pequeño-Ledezma y E. Buendía-Rodríguez. 2020. Estructura y diversidad de un bosque de galería en el noreste de México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 11(58):134-153. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v11i58.591. [ Links ]

Buendía-Rodríguez, E., E. Treviño-Garza, E. Alanís-Rodríguez, O. Aguirre-Calderón, M. González-Tagle y M. Pompa-García. 2019. Estructura de un ecosistema forestal y su relación con el contenido de carbono en el noreste de México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 10(54):4-25. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i54.149. [ Links ]

Contreras, F., C. Leaño, J. C. Licona, E. Dauber, L. Gunnar, N. Hager y C. Caba. 1999. Guía para la Instalación y Evaluación de Parcelas Permanentes de Muestreo (PPMs). Editora El País. Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia. 59 p. [ Links ]

Corral, J., O. A. Aguirre, J. Jiménez y S. Corral. 2005. Un análisis del efecto del aprovechamiento forestal sobre la diversidad estructural en el Bosque Mesófilo de Montaña “El Cielo”, Tamaulipas, México. Investigación Agraria. Sistemas y Recursos Forestales 14(2):217-228. https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/IA/article/view/2278 (7 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Corral-Rivas, J. J., B. Vargas, C. Wehenkel, O. Aguirre, G. Álvarez y A. Rojo. 2008. Guía para el Establecimiento de Sitios de Investigación Forestal y de Suelos en Bosques del Estado de Durango. Editorial UJED. Durango, Dgo., México. 81 p. [ Links ]

Corral-Rivas, S. y J. Navar-Cháidez. 2009. Comparación de técnicas de estimación de volumen fustal total para cinco especies de pino de Durango, México. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 15(1):5-13. https://revistas.chapingo.mx/forestales/?section=articles&subsec=issues&numero=39&articulo=502 (7 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Delgado, D. A., S. A. Heynes, M. D. Mares, N. L. Piedra, F. I. Retana, K. Rodríguez y L. Ruacho-Gonzá́lez. 2016. Diversidad y estructura arbórea de dos rodales en Pueblo Nuevo, Durango. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 7(33):94-107. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v7i33.92. [ Links ]

Domínguez, T. G., B. N. Hernández, H. González, I. Cantú, E. Alanís y M. Alvarado. 2018. Estructura y composición de la vegetación en cuatro sitios de la Sierra Madre Occidental. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 9(50):9-34. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v9i50.227. [ Links ]

Estrada, O. y S. G. Rodríguez. 2021. Más de 100 años de cultivo al bosque en Chihuahua. Caso Ejido El Largo y Anexos. Dirección Técnica Forestal de Ejido El Largo y Anexos. Chihuahua, Chih., México. 143 p. [ Links ]

Gadow, K., A. Rojo, J. G. Álvarez y R. Rodríguez. 1999. Ensayos de crecimiento: parcelas permanentes, temporales y de intervalo. Investigación Agraria. Sistemas y Recursos Forestales 8(Extraordinario 1):299-310. Doi: . https://doi.org/10.5424/644. [ Links ]

Gadow, K., C. Y. Zhang, C. Wehenkel, A. Pommerening, J. J. Corral-Rivas, M. Korol and X. H. Zhao. 2012. Forest structure and diversity. In: Pukkala, T. and K. von Gadow (comp.). Continuous Cover Forestry. Springer. Heidelberg, Germany., Netherlands. pp. 29-83. [ Links ]

García, S. A., E. Alanís, O. A. Aguirre, E. J. Treviño y G. Graciano. 2020. Regeneración y estructura vertical de un bosque de Pseudotsuga menziesii (Mirb.) Franco en Chihuahua, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 11(58):92-111. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v11i58.665. [ Links ]

García, S. A., R. Narváez, J. M. Olivas y J. Hernández. 2019. Diversidad y estructura vertical del bosque de pino-encino en Guadalupe y Calvo, Chihuahua. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 10(53):42-63. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i53.173. [ Links ]

González-Elizondo, S., M. González-Elizondo, J. Tena-Flores, L. Ruacho-González y L. López-Enríquez. 2012. Vegetación de la Sierra Madre Occidental, México: una síntesis. Acta Botanica Mexicana 100:351-403. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/abm100.2012.40. [ Links ]

Graciano-Ávila, G., E. Alanís-Rodríguez, O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, M. A. González-Tagle, E. J. Treviño-Garza y A. Mora-Olivo. 2017. Caracterización estructural del arbolado en un ejido forestal del noroeste de México. Madera y Bosques 23(3):137-146. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.2017.2331480. [ Links ]

Graciano-Ávila, G., E. Alanís-Rodríguez, O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, M. A. González-Tagle, E. J. Treviño-Garza, A. Mora-Olivo y E. Buendía-Rodríguez. 2019. Estimación de volumen, biomasa y contenido de carbono en un bosque de clima templado-frío de Durango, México. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 42(2):119-127. https://www.revistafitotecniamexicana.org/documentos/42-2/4a.pdf (1 de diciembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Graciano-Ávila, G., E. Alanís-Rodríguez, Ó. A. Aguirre-Calderón, M. A. González-Tagle, E. J. Treviño-Garza, A. Mora-Olivo y J. J. Corral-Rivas. 2020. Cambios estructurales de la vegetación arbórea en un bosque templado de Durango, México. Acta Botanica Mexicana 127:e1522. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/abm127.2020.1522. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, A., F. García, S. Rojas y F. Castro. 2015. Parcela permanente de monitoreo de bosque de galería, en Puerto Gaitán, Meta. Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria, 16(1):113-29. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21930/rcta.vol16_num1_art:385. [ Links ]

Hernández, L. y C. Reyna. 2015. Manual de campo para el establecimiento y remedición de parcelas permanentes de muestreo forestal en el Parque Nacional Machalilla. Departamento de Edición y Publicación Universitaria (DEPU). Editorial Mar Abierto. Manta, Manabí, Ecuador. 50 p. [ Links ]

Hernández-Salas, J., O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, E. Alanís-Rodríguez, J. Jiménez-Pérez, E. J. Treviño-Garza, M. A. González-Tagle, C. Luján-Álvarez, J.M. Olivas-García y A. Domínguez-Pereda. 2013. Efecto del manejo forestal en la diversidad y composición arbórea de un bosque templado del noroeste de México. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 19(2):189-199. Doi: https://doi.org/10.5154/r.rchscfa.2012.08.052. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2008. Conjunto de datos vectoriales escala 1: 1000000. Unidades climáticas. http://www.beta.inegi.org.mx/temas/mapas/climatologia/ (10 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2014. Conjunto de datos vectorial edafológico escala 1: 250000 Serie II (Continuo Nacional). http://www.inegi.org.mx/geo/contenidos/recnat/edafologia/vectorial_serieii.aspx (10 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). 1996. Chapter 5: Land Use Change and Forestry. En G. G. Manual, IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories, Revised Version. London, United Kingdom. 57 p. http://www.ipcc.ch/ (25 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Jiménez, J., O. A. Aguirre y H. Kramer. 2001. Análisis de la estructura horizontal y vertical en un ecosistema multicohortal de pino-encino en el norte de México. Investigación Agraria. Sistemas y Recursos Forestales 10(2):355-366. http://www.inia.es/IASPF/2001/vol10-2/jimen.PDF (24 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

López-Hernández, J. A., O. A. Aguirre-Calderón, E. Alanís-Rodríguez, J. C. Monarrez-Gonzalez, M. A. González-Tagle y J. Jiménez-Pérez. 2017. Composición y diversidad de especies forestales en bosques templados de Puebla, México. Madera y Bosques 23(1):39-51. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.2017.2311518. [ Links ]

Magaña T., O. S., J. M. Torres R., C. Rodríguez, H. Aguirre y A. M. Fierros. 2008. Predicción de la producción y rendimiento de Pinus rudis Endl. en Aloapan, Oaxaca. Madera y Bosques 14(1):5-13. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.2008.1411214. [ Links ]

Margalef, R. 1972. Homage to Evelyn Hutchison, or why is there an upper limit to diversity. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 44:211-235. https://digital.csic.es/handle/10261/166281 (15 de noviembre de 2021). [ Links ]

Márquez, M. A., S. González y R. Álvarez. 1999. Componentes de la diversidad arbórea en bosques de pino encino de Durango, Méx. Madera y Bosques 5(2):67-78. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.1999.521348. [ Links ]

Martínez, M., G. Sosa, J. M. Chacón, A. Pinedo, F. Villarreal y J. A. Prieto. 2019. El monitoreo forestal por medio de Sitios Permanentes de Investigación Silvícola en Chihuahua, México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 10(55):56-78. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i55.511. [ Links ]

Martínez, R. A., O. A. Aguirre, B. Vargas, J. Jiménez, E. J. Treviño y J. I. Yerena. 2016. Modelación de biomasa y carbono arbóreo aéreo en bosques del estado de Durango. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 7(35):91-105. Doi:https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v7i35.77. [ Links ]

Medrano, M., F. J. Hernández, S. Corral y J. A. Nájera. 2017. Diversidad arbórea a diferentes niveles de altitud en la región de El Salto, Durango. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 8(40):57-68. Doi: https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v8i40.36. [ Links ]

Návar-Cháidez, J. J. 2009. Allometric equations for tree species and carbon stocks for forests of northwestern Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 257(2):427-434. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.09.028. [ Links ]

Návar-Cháidez, J. J. 2010. Biomass allometry for tree species of northwestern Mexico. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 12(3):507-519. http://www.revista.ccba.uady.mx/urn:ISSN:1870-0462-tsaes.v12i3.391 (27 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Návar-Cháidez, J. y S. González-Elizondo. 2009. Diversidad, estructura y productividad de bosques templados de Durango, México. Polibotánica 27(1):71-87. https://www.polibotanica.mx/ojs/index.php/polibotanica/article/view/785/1009 (27 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Ni, Y., G. S. Eskeland, J. Giske and J.P. Hansen. 2016. The global potential for carbon capture and storage from forestry. Carbon Balance and Management 11(3):1-8. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13021-016-0044-y. [ Links ]

Pretzsch, H. 2009. Forest Dynamics, Growth and Yield. From Measurement to Model. Springer-Verlag. Heidelberg, Germany. 664 p. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Laguna, R., J. Jiménez-Pérez, O. A. Aguirre-Calderón y E. Jurado-Ibarra. 2007. Ecuaciones alométricas para estimar biomasa aérea en especies de encino y pino en Iturbide, N. L. Ciencia Forestal en México 32(101):39-56. https://cienciasforestales.inifap.gob.mx/editorial/index.php/forestales/article/view/827 (28 de noviembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Ortiz, G., V. A. González-Hernández, A. Aldrete, H. M. De Los Santos-Posadas, A. Gómez-Guerrero y A. M. Fierros- González. 2011. Modelos para estimar crecimiento y eficiencia de crecimiento en plantaciones de Pinus patula en respuesta al aclareo. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 34(3):205-212. https://revistafitotecniamexicana.org/documentos/34-3/8a.pdf (14 de octubre de 2021). [ Links ]

Rojas-García, F., B.H.J. De Jong and P. Martínez-Zurimendí. 2015. Database of 478 allometric equations to estimate biomass for Mexican trees and forests. Annals of Forest Science 72:835-864. Doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-015-0456-y. [ Links ]

Shannon, C. E. 1948. The mathematical theory of communication. The Bell System Technical Journal 27(3):379-423. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1538-7305.1948.tb01338.x. [ Links ]

Silva-Flores, R., G. Pérez-Verdín and C. Wehenkel. 2014. Patterns of Tree Species Diversity in Relation to Climatic Factors on the Sierra Madre Occidental, Mexico. PloS one 9(8):e105034. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0105034. [ Links ]

Solís, R., O. A. Aguirre, E. J. Treviño, J. Jiménez, E. Jurado y J. Corral-Rivas. 2006. Efecto de dos tratamientos silvícolas en la estructura de ecosistemas forestales en Durango, México. Madera y Bosques 12(2):49-64. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.2006.1221242. [ Links ]

Valenzuela, L. M. y D. Granados. 2009. Caracterización fisonómica y ordenación de la vegetación en el área de influencia de El Salto, Durango, México. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 15(1):29-41. https://revistas.chapingo.mx/forestales/?section=articles&subsec=issues&numero=39&articulo=505 (16 de diciembre de 2020). [ Links ]

Zúñiga, J.M., E.A. Martínez, C. Navarrete, J. Graciano, D. Maldonado y B. Cano. 2018. Análisis ecológico de un área de pago por servicios ambientales hidrológicos en el ejido La Ciudad, Pueblo Nuevo, Durango, México. Investigación y Ciencia de la Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes 26(73):27-36. Doi: https://doi.org/10.33064/iycuaa201873204. [ Links ]

Received: March 31, 2021; Accepted: January 13, 2022

texto en

texto en