Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.11 no.57 México ene./feb. 2020 Epub 20-Jun-2020

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v11i57.617

Scientific article

Sample size for estimating fuel loads in oak forest in the Mountain Region of Guerrero State

1Universidad Intercultural del Estado de Guerrero. México.

2Departamento Forestal. Universidad Autónoma Agraria Antonio Narro. México.

3Facultad de Ciencias Forestales, Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. México.

4Departamento BEECA sección Ecología. Facultat de Biología. Universitat de Barcelona. España.

Fuel is the only component of the triangle of fire behavior that can be manipulated in prescribed burns for the prevention of large forest fires, so estimating fuel loads will allow designing strategies for the management of forest resources. Fifteen sampling sites were determined in a random manner for the measurement of fuels 1, 10, 100 and 1 000 h based on the planar intersection technique. At the end of each line, leaf litter samples were collected in 0.09 m2, which were dried in an oven at 70 °C. The fuel load in the area was 11.11 t ha-1, 65.53 % corresponded to litter and 34.47 % to woody fuels. The comparison of Kruskal-Wallis range means by fuel type showed significant differences in leaf litter with 1, 10, 100 and 1 000 h (p <0.001) and 1 000 h with 1, 10, 100 h (p<0.05); the leaf litter values> 1000> 100> 10> 1 h. There was a significant correlation between the thickness of the litter layer (cm) and litter load (t ha-1) with (r = 0.773, p<0.001). Based on the results the area is susceptible to a superficial fire.

Key words Correlation; leaf litter; forest fire; Malinaltepec; prescribed burns; Quercus sp

El combustible es el único componente del triángulo de comportamiento del fuego que puede ser manipulado en quemas prescritas para la prevención de grandes incendios forestales, por ello estimar las cargas de combustible permitirá diseñar estrategias para el manejo de los recursos forestales. Se determinaron 15 sitios de muestreo de manera aleatoria para la medición de combustibles 1, 10, 100 y 1 000 h con base en la técnica de intersecciones planares. Al final de cada línea se colectaron muestras de hojarasca en 0.09 m2, que fueron secadas en estufa a 70 °C. La carga de combustible en el área fue de 11.11 t ha-1, 65.53 % correspondió a la hojarasca y 34.47 % a combustibles leñosos. La comparación de medias de intervalos de Kruskal-Wallis por tipo de combustible evidenció diferencias significativas en hojarasca con 1, 10, 100 y 1 000 h (p < 0.001); 1 000 h con 1, 10, 100 h (p < 0.05); los valores de hojarasca >1000 >100 >10 >1 h. Se evidenció una correlación significativa entre el espesor de la capa de hojarasca (cm) y carga de hojarasca (t ha-1) con (r = 0.773; p < 0.001). A partir de los resultados, el área es susceptible a un incendio superficial.

Palabras clave Correlación; hojarasca; incendio forestal; Malinaltepec; quemas prescritas; Quercus sp

Introduction

Forest fires are one of the main anthropogenic disturbances in the ecosystems of Mexico (Rentería-Anima et al., 2005), as well as one of the main causes of deterioration and deforestation (Morfin et al., 2012) production and release of gases and particles into the atmosphere as a result of combustion (Castañeda-González et al., 2012), which contribute too climate change.

The occurrence and the behavior of forest fires are influenced by the type of fuels, the atmospheric time and topography (DeBano, 1998). Forest fires are produced in the presence of long droughts, as there is enough fuel, and the vegetal cover has the necessary continuity for the fire to spread (Santiago et al., 1999). Fuel is the only element that can be manipulated for fighting forest fires and applying preventive measures (Morfín et al., 2012); as it is well known, areas with high fuel loads emit more heat and cause more intense fires (Vélez, 2000), producing devastating impacts on the environment. For this reason, the assessment of fuels will allow orienting the alternatives in the prevention and management of fires in forest ecosystems to avoid soil erosion and the loss of goods and services, and to preserve the biodiversity and the hydrological cycle, among other benefits.

Fuel loads are quite varied, as shown by the results of Rubio et al. (2016) when comparing between fuel loads in pine-oak forests with and without the presence of fires (36.6 t ha-1 and 49.6 t ha-1; p < 0.001) in Iturbide, Nuevo León. Chávez et al. (2016) registered 92.49 t ha-1 in oak forests in the state of Jalisco, and López et al. (2015) 14 t ha-1 of leaf litter in an oak forest dominated by Quercus magnoliifolia Née and Q. conspersa Benth. in Guerrero. For this reason, it is convenient to carry out research by ecosystem and by region, as well as on the potential factors that condition such differences.

With regard to the number of sites for the assessment of forest fuels, Castañeda et al. (2015) established 30 sites in Pinus hartwegii Lindl. forests; Hernández et al. (2016) established 15 sites in three ecosystems with incidence of fires in Juchitán, Oaxaca, and Barrios-Calderón et al. (2018) established 24 sampling sites in the La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas. Nevertheless, fuel studies do not consider a statistical criterion for determining the sampling site.

For this reason, the following research objectives were formulated: i) to determine the number of sites for estimating the loads of woody fuels and leaf litter in the study area, ii) to assess the variation of the fuel loads by site and by type, and iii) to evaluate the effect of the slope (%) and the thickness of the leaf litter layer (cm) on woody fuels and leaf litter.

Materials and Methods

Study area

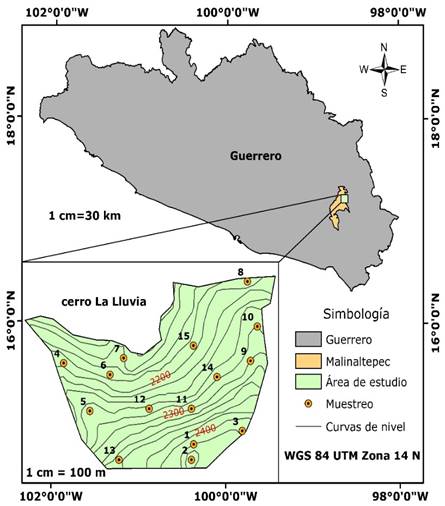

The La Lluvia mountain is located in the community of La Ciénaga, in Malinaltepec, Guerrero, at the coordinates 17º13’42.99’’ N and 98º38’3.01’’ W. Its altitude ranges between 2 120 and 2 440 masl (Figure 1). The climate is semi-warm subhumid A(C) w2 (w) (INEGI, 2008); the mean annual precipitation is 2000 mm (INEGI, 2006), and the mean annual temperature, 18 °C (INEGI, 2007). The mountain is located in the southern Pacific hydrological-administrative Region, in the upper part of the basin of the Omitlán river. This is not only a strategic conservation area but also a source of water supply for the community of La Ciénaga, Malinaltepec, Guerrero.

Simbología = Simbology; Área de studio = Study area; Muestreo = Sampling; Curvas de nivel = Contour line.

Figure 1 Location of the study area and distribution of the sampling sites.

Vegetation is made up of an oak forest (Inegi, 2017), where the tree stratum forms a semi-closed canopy. The main species belong to the genus Quercus (Quercus elliptica Née, Quercus acutifolia Née, Quercus candicans Née, Quercus martinezii C. H. Mull., Quercus obtusata Bonpl., Quercus gentryi C. H. Mull., Quercus peduncularis Née); other species present in the area are Arbutus xalapensis Kunth, Befaria leavis Benth, Bejaria aestuans Mutis ex L., Vaccinium leucanthum Schltdl., Alnus acuminata Kunth, Ostrya virginiana (Mill) K.Koch, Clethra kenoyeri Lundell, Clethra hartwegii Britton, Licaria aff. capitata (Chamisso et Schlechtendal) Kosterm., Persea chrysantha Lorea-Hern., Clusia multiflora Kunth, Magnolia schiedeana Schltdl., Miconia glaberrima (Schlechtendal) Naudin., Fraxinus uhdei (Wenz.) Lingelsh., Phyllonoma laticuspis (Turcz.) Engl., Styrax argenteus C. Presl. and Daphnopsis nevlingii J. Jiménez Ram.

In order to determine the surface area, the vertices of the polygon comprising the mountain were georeferenced using a Global Positioning System (GPS, Garmin, eTrex 20x); the total surface area, of 44 ha, was subsequently determined using the ArcGis software, version 10.2.

Sample size and sampling design

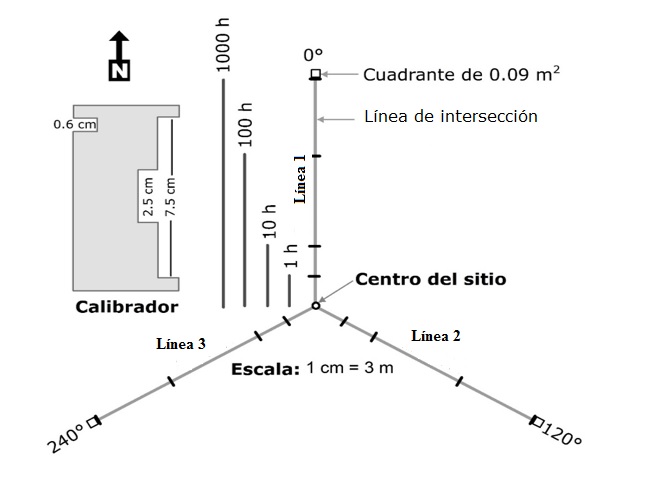

The distribution of the sampling sites across the 44 ha was random; the Create Random Points tool of ArcGis 10.2 was used to adequately establish the sites (Figure 1). The amount of fuel per category -woody and fine litter- was expressed by size classes that determine the time that the fuel takes to reach a balance with the atmospheric moisture, known as delay time (Xelhuantzi et al., 2011). The center of the sampling site was determined in the field with the aid of a GPS (UGarmin, eTrex 20x) and marked with a stake; the slope (%) was determined in each site using a BruntonTM clinometer. Three planar interception lines oriented at 0°, 120° and 240° of azimuth with a BruntonTM compass; the lines were 15 m long.

The woody fuels were quantified according to the planar intersections technique based on a count of branches or stems that intersect the vertical plane defined by a transect (Brown, 1971); the 1 h fuels were counted at 2 m (0-0.6 cm); 10 h fuels were counted at 4 m, (0.6-2.5 cm), and 100 h fuels were registered at 10 m (2.6-7.5 cm), with the measures pre-established in a handmade caliper, and the 1 000 h fuel was registered along the whole 15 m line (>7.5 cm) -divided between healthy and rotting-, whose diameter was measured directly with a Truper T-3ME flexometer (Figure 2).

Línea = Line; Línea de intersección = Intersection line; Calibrador = Caliper; Cuadrante = Square; Centro del sitio = Site center.

Figure 2 Sampling site for quantifying woody fuels and leaf litter.

The leaf litter was quantified in a 30 × 30 cm square at the end of each planar interception line, resulting in a total of 45 samples; the thickness of the leaf litter layer was measured using a BarrilitoTM ruler calibrated in cm. All the leaf litter collected in the 0.09 m2 was introduced into brown paper bags; the bags were labeled and transported to the laboratory in order to obtain their dry weight.

Ten pre-sampling sites were surveyed in order to estimate the sample size (n); the sum of the 1 and 10 h fuel loads and the leaf litter per site were used for estimating the coefficient of variation (𝑆𝑥%) when occurring at all the sites; the final sample was determined using the following formula (Ancira-Sánchez and Treviño, 2015):

Where:

Based on the previous formula, 15 sampling sites were determined for the study area, distributed across the 44 ha, with a coefficient of variation 𝑆𝑥% = 54.86 %.

Laboratory work

The leaf litter samples collected in the field were taken to the Biological Sciences Laboratory of the Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero. The dry weight was determined from the drying process in a Felisa® oven at 70 oC; the leaf litter was monitored periodically until a constant weight was obtained, measured with a NOVAL TH-II scale with 0.1 g accuracy. The woody fuels were estimated using the formulas proposed by Brown, 1971 (Table 1). The leaf litter load was calculated using the dry weight, which was extrapolated to t ha-1 using the following formula:

Where:

LLL = Leaf litter load (t ha-1)

LDW = Litter dry weight (g) in 0.09 m2 (30 × 30 cm)

0.1111 = Factor of conversion from g in 0.09 m2 into t ha-1

Table 1 Formulas for estimating the weight of woody fuels (Brown, 1971).

| Diameter class (cm) | Time of delay | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| 0-0.6 | 1 h |

|

| 0.6-2.5 | 10 h |

|

| 2.6-7.5 | 100 h |

|

| >7.5 (without rotting) | 1 000 h |

|

| >7.5 (with rotting) | 1 000 h |

|

W = Fuel weight in t ha-1; F = Number of intersections; C = Slope correction factor (%); N = Number of lines per site de; L = Length of the sampling line or sum of the lengths of the lines in linear feet [ft]: 1 m = 3.28 ft; d 2 = Square diameter of woody pieces larger than 7.5 cm, and 0.488, 3.369, 36.808, 1.46 and 1.21 = Specific weight constant.

Statistical analysis

The loads per site (15 sites, 3 lines per site) were estimated using the data of 1, 10, 100, 1000 h fuel and leaf litter; an analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 95 % confidence level was subsequently carried out in order to detect statistical differences between the sites for a given fuel; when significant differences were found, a Tukey mean comparison test (α = 0.05) was performed.

Analyses were also made to find statistical differences between fuel types (1, 10, 100, 1 000 h and leaf litter; n = 45); since the data do not follow a normal distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis non parametric mean comparison test was applied (Kruskal and Wallis, 1952). Finally, correlations were made between the 1 h, 10 h and 100 h fuels and dead litter (t ha-1) with the land slope (%) and the thickness of the litter layer (cm). All the statistical procedures were made by using the IBM SPSS Statistics software, 20 version (SPSS, 2011).

Results and Discussion

Total fuel load

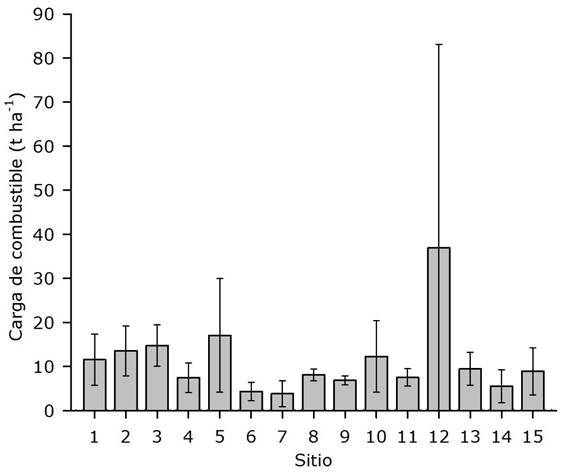

The average fuel load at the 15 sampling sites was 11.11 t ha-1; the maximum value was found at site 12 (36.90 t ha-1), and the minimum value, at site 7 (3.82 t ha-1), without significant differences P = 0.36 (Figure 3). The average obtained, is below that reported by Rodríguez and Sierra (1995), of 13.33 t ha-1, in a broadleaf forest in the State of Mexico; Xelhuantzi et al. (2011) obtained 17.90 t ha-1 in pine-oak forests of the states of Coahuila, Puebla and Jalisco, and Rubio et al., (2016) registered up to 36.6 t ha-1 in pine-oak forests of a fire-free area in Nuevo León.

The means were statistically equal (Tukey mean comparison test; n = 3, F = 1.14, and W = 0.36). The bars represent the standard deviation.

Figure 3 Total forest fuel load by site in an oak forest of the La Lluvia mountain.

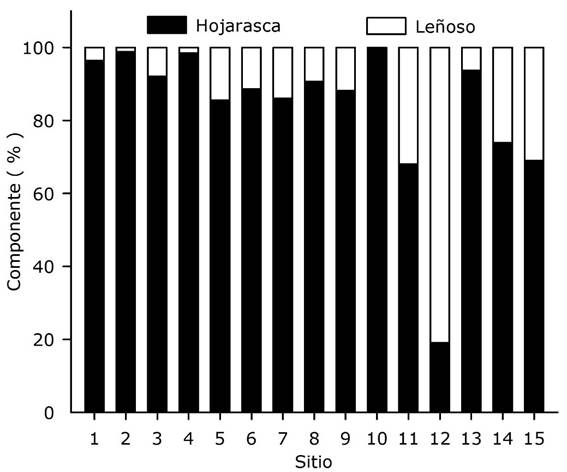

The mean litter load was 7.28 t ha-1 (65.53 %); this was the most representative material in the study area, where the values ranged between 97.72 and 18.10 % at sites 10 and 12, respectively (Figure 4). Similar values, of with 7.33 t ha-1, were reported by Hernández et al. (2016). Rubio et al. (2016) registered similar values to those of this research, namely 8.52 and 8.64 t ha-1 of litter in pine-oak forests with and without burn, respectively. López et al. (2015) recorded high litter values, of 14 t ha-1, in a 0.5 ha plot dominated by Q. magnoliifolia and Q. conspersa; however, they never reported the woody component, which leads to the assumption that it was absent or contributed little to the total fuel load of that area.

Componente = Component; Sitio = Site; Hojarasca = Litter; Leñoso = Woody component.

Figure 4 Percentage of woody fuel and leaf litter per site.

The woody fuel load registered exhibited low values, amounting to merely 3.87 t ha-1 (34.47 %) of the total load; the highest value occurred at site 12 (81.90 %), and the lowest, at site 10 (2.28 %); the result was above the figures registered by Hernández et al. (2016), with 2.32 t ha-1 for the oak ecosystem in Juchitán, Oaxaca; Rubio et al. (2016) registered values of 18.31 and 15.84 t ha-1 when comparing between the fuel loads of pine-oak forests with and without burn, respectively.

The variation in the fuel loads differs at a spatial scale within an ecosystem, as suggested by the results of Chávez et al. (2016), who registered up to 92.49 t ha-1 for the oak forest in the state of Jalisco; conversely, Villers and López (2004) quantified fuel loads in oak forests of the La Malinche National Park in Tlaxcala, as 16.3 t ha-1 of woody material and 0.27 m of thickness for the topsoil.

Fuel loads per site

According to the results of the ANOVA performed for the various fuel categories per site, leaf litter exhibited no significant differences (p = 0.36); the maximum value of the litter fuel of 12.77 t ha-1, was found at site 2; the lowest values were registered at sites 7 and 14, at 2.63 t ha-1 (Table 2). In this regard, Martínez et al. (1990) consider that a high accumulation of litter contributes to a higher incidence of fires, and its presence and thickness will determine the magnitude of the fire, as it can be easily ignited.

Table 2 Tukey mean comparison between sites for forest fuels in oak forest.

| Site | n | Fuel load (t ha-1) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 h | 10 h | 100 h | 1 000 h | Leaf litter | Total | ||

| 1 | 3 | 0.18 a | 0.44 a | 0.38 a | - | 10.55 a | 11.55a |

| 2 | 3 | 0.42 ab | 0.34 a | - | - | 12.77 a | 13.54a |

| 3 | 3 | 0.62 ab | 0.49 a | 1.28 a | - | 12.36 a | 14.75a |

| 4 | 3 | 0.40 ab | 0.20 a | - | - | 6.85 a | 7.44a |

| 5 | 3 | 0.67 ab | 1.02 a | 2.67 a | - | 12.70 a | 17.06a |

| 6 | 3 | 0.46 ab | 0.28 a | 0.41 a | - | 3.18 a | 4.33a |

| 7 | 3 | 0.36 ab | 0.45 a | 0.39 a | - | 2.63 a | 3.82a |

| 8 | 3 | 0.88 b | 1.32 a | - | - | 4.55 a | 8.09a |

| 9 | 3 | 0.77 ab | 0.86 a | 1.34 a | - | 4.78 a | 6.87a |

| 10 | 3 | 0.10 a | 0.18 a | - | - | 12.00 a | 12.28a |

| 11 | 3 | 0.68 ab | 1.23 a | 1.16 a | 0.61 a | 3.84 a | 7.52a |

| 12 | 3 | 0.43 ab | 0.52 a | 3.05 a | 26.22 a | 6.68 a | 36.90a |

| 13 | 3 | 0.17 a | 0.95 a | 0.38 a | - | 7.94 a | 9.45a |

| 14 | 3 | 0.91 b | 0.99 a | 0.87 a | - | 2.73 a | 5.50a |

| 15 | 3 | 0.51 ab | 0.21 a | 0.46 a | 2.10 a | 5.64 a | 8.92a |

|

|

0.50 | 0.63 | 0.77 | 1.93 | 7.28 | 11.11 | |

|

|

0.03 | 0.10 | 0.64 | 14.38 | 3.84 | 7.97 | |

|

|

49.68 | 62.13 | 91.56 | 149.05 | 52.79 | 80.06 | |

The 1 h fuels were in average 0.50 t ha-1 (4.50 %) of the total quantified fuel, with maximum and minimum values of 0.10 to 0.91 t ha-1 (Table 2). This load is below the values reported by Muñoz et al. (2005), of 0.70 t ha-1, but higher than that reported by Villers and López (2004), of 0.42 t ha-1. The contribution of this category to the total load was low.

The variance analysis showed significant differences in this category (p = 0.001). The Tukey mean comparison test indicated low values at sites 10 and 1, of 0.10 to 0.18 t ha-1; conversely, the highest values, of 0.88 y 0.91 t ha-1, were found at sites 8 and 14. Barrios-Calderón et al. (2018) registered differences between mangrove sites, with values of 5.39 and 2.85 t ha-1; Castañeda et al. (2015) reported differences in high mountain forests dominated by Pinus hartweggi (p = 0.0399) in forests with a dense cover and forests with semi-dense and fragmented covers.

The 10 h fuel was quantified at 0.63 t ha-1 (5.67 %); the maximum and minimum values ranged between 0.35 and 0.05 t ha-1 at sites 8 and 10 (Table 2); no significant differences were found (p = 0.17). In contrast, Castañeda et al. (2015) quantified high values, of 3.82, 4.48 and 5.18 t ha-1, for dense, semi-dense and fragmented covers (p = 0.23).

Non significant differences were found in the 100 h fuel (p = 0.61); the average value was 0.77 t ha-1 (6.93 %), while the highest and lowest values, of 3.05 and 0.38 t ha-1, were registered at sites 12 and 1 (Table 2). Xelhuantzi et al. (2011) registered lower values, of 0.3 t ha-1, in forests dominated by pine and oak species in the states of Coahuila, Puebla and Jalisco.

Finally, 1 000 h fuels exhibited values of 0.61 to 26.22 t ha-1 at sites 11 and 12, respectively (Table 2); these fuels were registered only at three of the 15 sites, with an average of 1.93 t ha-1 (17.37 %), and without significant differences (p = 0.42). This is a higher value than the 0.43 t ha-1 found by Chávez et al. (2016) for 1 000 h fuel in a rotten condition for a pine-oak forest of the state of Jalisco. Likewise, in this study, all the material quantified in this category was found in a state of decay, and therefore it entails little danger, as it will soon be incorporated into the organic layer of the soil.

Forest fuels by type

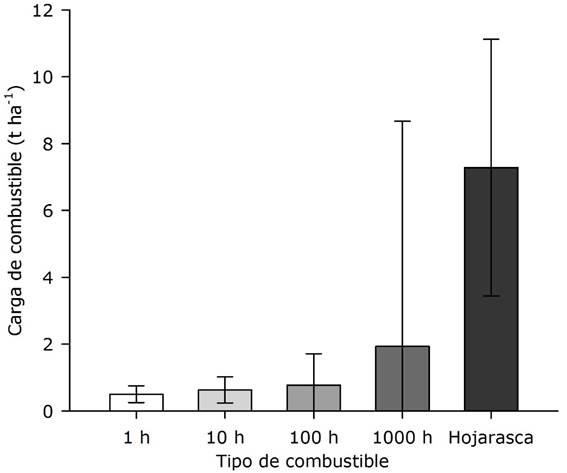

Regarding the loads of the various types of forest fuels, the highest value is for leaf litter, i.e. 65.53 % (7.28 t ha-1), followed by the 1 000 h fuels, with 17.37 % (1.93 t ha-1); 100 h fuel, with 6.93 % (0.57 t ha-1); 10 h fuel, with 5.67 % (0.169 t ha-1), and 1 h fuel, with 4.50 % (0.067 t ha-1) (Figure 5). These differ from the loads reported by Xeluantzi et al. (2011), who estimated 6.19 t ha-1 for leaf litter; 0.30 t ha-1, for 10 h; 0.12 t ha-1 for 100 h, and 0.03 t ha-1 for 1 h fuel in clusters of temperate forests distributed between Coahuila, Puebla and Jalisco.

Carga de combustible = Fuel load; Tipo de combustible = Type of fuel; Hojarasca = Litter.

Vertical lines represent the standard deviation.

Figure 5 Load by type of fuel in the oak forest in Guerrero, Mexico.

The Kruskal-Wallis mean comparison test exhibited significant differences between leaf litter and the 1, 10, 100 and 1 000 h fuel types (p <0.001), and between 1000 h fuel and 1, 10 and 100 h fuels (p = 0.002, 0.002 and 0.023); the rest of the comparisons did not show significant differences, with p > 0.05 (Table 3). Given the higher litter fuel load, a superficial fire may be expected; although the component of the 1 000 h fuel registered the second most important load, its distribution was incipient, since it was registered only at 3 of the 15 sites.

Table 3 Kruskal-Wallis mean comparison test by type.

| Comparison | Statistic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| X2 | p | ||

| 1 h | 10 h | 0.76 | 0.38 |

| 100 h | 0.08 | 0.77 | |

| 1 000 h | 9.93 | 0.002* | |

| Leaf litter | 21.77 | <0.001* | |

| 10 h | 100 h | 0.23 | 0.63 |

| 1 000 h | 9.93 | 0.002* | |

| Leaf litter | 21.77 | <0.001* | |

| 100 h | 1 000 h | 5.17 | 0.023* |

| Leaf litter | 20.68 | <0.001* | |

| 1 000 h | Leaf litter | 17.46 | <0.001* |

*= Significant (p ≤ 0.05)

Slope and depth of leaf litter with fuels

The correlation between the thickness and the load of the litter layer was positive, with r = 0.773 and p = 0.001 (Table 4); the thickness of the layer was 3.18 ± 1.28 cm, i.e. lower than the thickness registered by Estrada and Ángeles (2007) for the oak forests of the El Chico National Park in Hidalgo. Likewise, the relationship between the slope of the terrain and the 1 h fuel was positive and significant, with r = 0.639 and p = 0.010 (Table 4); the largest loads (0.91 t ha-1) occurred at the most pronounced slope (75 %). This result contradicts those of Villers et al. (2012), who registered higher fuel loads at sites with the least slope as a result of dragging due to gravity or runoff. For their part, Castañeda et al. (2015) found a positive correlation between 1 000 h fuels in dense forests with slopes ranging between 7 and 12° (p = 0.049).

Table 4 Spearman’s correlation between the slope (%) and the thickness of the litter layer (cm) with 1, 10, 100 h fuels and leaf litter in oak forests.

| Correlation | n | r | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slope (%) | 1 h | 15 | 0.639 | 0.010 |

| 10 h | 15 | 0.131 | 0.643 | |

| 100 h | 11 | 0.299 | 0.372 | |

| Leaf litter | 15 | -0.250 | 0.368 | |

| Thickness (cm) | 1 h | 15 | -0.304 | 0.270 |

| 10 h | 15 | 0.091 | 0.746 | |

| 100 h | 15 | 0.358 | 0.279 | |

| Leaf litter | 15 | 0.773 | 0.001 | |

| 1 h | 10 h | 15 | 0.650 | 0.009 |

| 100 h | 11 | 0.579 | 0.062 | |

| Leaf litter | 15 | -0.368 | 0.177 | |

| 10 h | 100 h | 11 | 0.451 | 0.164 |

| Leaf litter | 15 | -0.236 | 0.398 | |

| 100 h | Leaf litter | 11 | 0.251 | 0.457 |

n = Pairs of data; r = Coefficient of correlation; p = Probability

Among the various fuel types, a positive and significant relationship was found only between the loads of the 1 and 10 h fuels, with r = 0.650 and p = 0.009 (Table 4), which is reasonable, as the wind and the rainfall naturally cause the detachment of small branches and twigs. For the rest of the fuels, as assumed by Xelhuantzi et al. (2011), increases in any type of fuel are independent from the rest of the categories and may be the result of other disturbance factors, such as fires, excessive felling, and grazing, which was not observed at the 15 sampling sites.

Conclusions

The 15 sampling sites for determining the fuel load turned out to be correct, according to the estimation of the sample size, having a variation coefficient of 54.86 %; this is confirmed by the statistical analysis, which showed no significant differences in relation to the sum of all the assessed fuels (P = 0.36). Significant differences were exhibited by site in the 1 h category, and by type between leaf litter and 1, 10, 100 and 1 000 h fuels, as well as between the 1 000 h fuel and the 1, 10 y 100 h fuels.

The highly significant correlation between the thickness and the load of leaf litter provides a guideline for estimating the litter load in situ, solely by measuring the thickness of the layer, which will facilitate its estimation and will contribute to fire management decision making and to the fight against forest fires.

The quantification of the forest fuel loads in the ecosystems is extremely valuable and helpful for determining the potential behavior and intensity of fires. Furthermore, it provides indispensable data for decision making in forest fire management, prevention and fighting.

Referencias

Ancira-Sánchez, L. y E. J. Treviño G. 2015. Utilización de imágenes de satélite en el manejo forestal del noreste de México. Madera y Bosques. 21(1): 77-91. Doi: 10.21829/myb.2015.211434. [ Links ]

Barrios-Calderón, R. J., D. Infante-Mata, J. G. Flores-Garnica, C. Tovilla-Hernández, S. J. Grimaldi-Calderón and J. R. García A. 2018. Woody fuel load in coastal wetlands of the La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve, Chiapas, México. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 24(3): 339-357. Doi: 10.5154/r.rchscfa.2017.12.068. [ Links ]

Brown, J. K. 1971. A planar intersects method for sampling fuel volume and surface area. Forest Science 17(1): 96-102. Doi: 10.1093/forestscience/17.1.96. [ Links ]

Castañeda-González J. C., A. Gallegos-Rodríguez, M. Sánchez-Durán y P. A. Domínguez-Calleros. 2012. Biomasa aérea y posibles emisiones de CO2 después de un incendio; caso del bosque "La Primavera", Jalisco, México. Ra Ximhai 8(3) 1-15. Doi: 10.35197/rx.08.03.e1.2012.01.jc. [ Links ]

Castañeda R., M. F., A. R. Endara A., M. L. Villers R. y E. G. Nava B. 2015. Evaluación forestal y de combustibles en bosques de Pinus hartwegii en el Estado de México según densidades de cobertura y vulnerabilidad a incendios. Madera y Bosques 21(2): 45-58. Doi: 10.21829/myb.2015.212444. [ Links ]

Chávez D., Á. A., J. Xelhuantzi C., E. A. Rubio C., J. Villanueva D., H. E. Flores L. y C. De la Mora O. 2016. Caracterización de cargas de combustibles forestales para el manejo de reservorios de carbono y la contribución al cambio climático. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. (13): 2589-2600. Doi: 10.29312/remexca.v0i13.485. [ Links ]

DeBano, L. F., D. G. Neary y P. F. Ffolliot. 1998. Fire's Effects on Ecosystems. John Wiley y Sons Inc. New York, NY, USA. 333 p. [ Links ]

Estrada C., I. y E. R. Ángeles C. 2007. Evaluación de combustibles forestales en el Parque Nacional “El Chico”, Hidalgo. Ecología y biodiversidad, claves de la prevención. Wildfire. Sevilla, España. 17 p. [ Links ]

Hernández G., J., G. Rodríguez O., J. R. Enríquez del V., G. V. Campos A. y A. Hernández H. 2016. Biomasa arbustiva, herbácea y en el piso forestal como factor de riesgo de incendios. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 7 (36): 51-63. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v7i36.59. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2006. Conjunto de datos vectoriales Precipitación media anual Escala 1:1000 000. Aguascalientes, Ags., México. s/p. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2007. Conjunto de datos vectoriales Temperatura media anual Escala 1:1000 000. Aguascalientes, Ags., México. s/p. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2008. Conjunto de datos vectoriales Unidades Climáticas Escala 1:1 000 000. Aguascalientes, Ags., México. s/p. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (Inegi). 2017. Conjunto de datos vectoriales de uso del suelo y vegetación Escala 1:250 000. Serie VI (Conjunto nacional). Aguascalientes, Ags., México. s/p. [ Links ]

López M., M. A., D. A. Rodríguez T., F. Santiago C., V. A. Sereno C. y D. Granados S. 2015. Tolerancia al fuego en Quercus magnoliifolia. Revista Árvore, Viçosa-MG 19 (3): 223-233. Doi:10.1590/0100-67622015000300013. [ Links ]

Martínez, A., J. G. Flores G. y J. de D. Benavides S. 1990. Índices de riesgo de incendio en la Sierra de Tapalpa, Estado de Jalisco. Ciencia Forestal en México 15(67): 3-34. [ Links ]

Morfin R., J. E., E. J. Jardel P., E. Alvarado C. y J. M. Michel F. 2012. Caracterización y cuantificación de combustibles forestales. Comisión Nacional Forestal-Universidad de Guadalajara. Guadalajara, Jal., México. 111 p. [ Links ]

Muñoz R., C. A., E. J. Treviño G., J. Verástegui C., J. Jiménez P. y O. Aguirre C. 2005. Desarrollo de un modelo espacial para la evaluación del peligro de incendios forestales en la Sierra Madre Oriental de México. Investigaciones geográficas 56: 101-117. Doi: 10.14350/rig.30099. [ Links ]

Kruskal, W. H. and Wallis W. A. 1952. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association 47(260): 583-621. Doi: 10.2307/2280779. [ Links ]

Rentería-Anima, J. B., E. J. Treviño-Garza, J. de J. Návar-Chaidez, O Aguirre-Calderón y I. Cantú-Silva. 2005. Caracterización de combustibles leñosos en el ejido Pueblo Nuevo, Durango. Revista Chapingo. Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 11(1): 51-56. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, D. A. y A. Sierra P. 1995. Evaluación de los combustibles forestales en los bosques del Distrito Federal. Ciencia Forestal en México 20(77): 193-218. [ Links ]

Rubio C., E. A., M. A. González T., J de D. Benavides S., A. A. Chávez D. y J. Xelhuantzi C. 2016. Relación entre necromasa, composición de especies leñosas y posibles implicaciones del cambio climático en bosques templados. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas . (13): 2601-2614. Doi: 10.29312/remexca.v0i13.486. [ Links ]

Santiago F. H., M. Servín M., H. C. Rodarte R. y F. J. Garfias A. 1999. Incendios Forestales y Agropecuarios: Prevención e impacto y restauración de los ecosistemas. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca, Instituto Politécnico Nacional. México, D.F., México. 178 p. [ Links ]

Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS). 2011. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows. Version 20.0. IBM Corp. New York, NY, USA. n/p. [ Links ]

Vélez, R. 2000. La defensa contra incendios forestales. Fundamentos y experiencias. Mc Graw Hill. Madrid, España. 1320 p. [ Links ]

Villers R., L. y J. López. 2004. Comportamiento del fuego y evaluación del riesgo por incendios en las áreas forestales de México: un estudio en el volcán de La Malinche. In: Villers. R. L. y J. López (ed.). Incendios forestales en México. Métodos de evaluación. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Centro de Ciencias de la Atmósfera. México, D. F., México. pp. 61-78. [ Links ]

Villers G., S., L. Villers R. y J. López B. 2012. Modelos que relacionan las características biofísicas del terreno con la presencia de combustibles forestales en las montañas centrales de México. Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles 59: 369-388. Doi: 10.21138/bage.1462. [ Links ]

Xelhuantzi C., J., J. G. Flores G. y Á. A. Chávez D. 2011. Análisis comparativo de cargas de combustibles en ecosistemas forestales afectados por incendios. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 2(3): 37-52. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v2i3.624. [ Links ]

Received: July 27, 2019; Accepted: November 11, 2019

texto en

texto en