Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.10 no.56 México nov./dic. 2019 Epub 30-Abr-2020

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i56.462

Scientific article

Mortality and health of provenances of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. in the coast of Oaxaca

1Centro Nacional de Investigación Disciplinaria en Conservación y Mejoramiento de Ecosistemas Forestales, INIFAP. México.

3Posgrado en Ciencias Forestales, Colegio de Postgraduados. México.

In Mexico, there is a knowledge gap on plant mortality and health of tropical forest plantations. Therefore, a provenances test of Enterolobium cyclocarpum was established in two sites (Pinotepa de Don Luis and Valdeflores) in the coastal region of Oaxaca, Mexico to determine the mortality factors and biotic agents related to the health of this specie. Mortality and plant health were recorded during 18 months; also, differences between sites and between provenances were determined. Orthogeomys grandis (pocket gopher) in Pinotepa de Don Luis (27.9 %) and drought (29.2 %) in Valdeflores caused higher plant mortality. Powdery mildews (Oidum), aphid (Aphis), cottony cochineal (Pseudoccocus longispinus), twig girdlers (Oncideres), borer (Lepidoptera) and defoliator (Lepidoptera) were the biotic agents related to health of E. cyclocarpum. The powdery mildews and the aphids infected the highest number of plants; in Pinotepa de Don Luis, the powdery mildews and the aphids infected 58.8, 29.2 % of the plants, respectively; whereas, in Valdeflores, the powdery mildews and aphids infected 3.3 % and 0.8 % of the plants, respectively. In Pinotepa de Don Luis, plants from Cortijo and Colotepec had the lowest powdery mildews infection, and the aphid infestation was not different in plants between provenances. In Valdeflores, plants from five provenances were free of powdery mildews infection, and the aphids only infested plant from the El Zarzal provenance. The location and precipitation of the sites influenced the levels mortality and infection of E. cyclocarpum plants.

Key words Aphis; Oidium; Oncideres; tropical plantations; Pseudococcus longispinus (Targioni Tozzetti; 1867); drought

En México existe un vacío de conocimiento sobre la mortalidad y sanidad de plantaciones forestales tropicales. Por tanto, un ensayo de procedencias de Enterolobium cyclocarpum se estableció en dos sitios (Pinotepa de Don Luis y Valdeflores) de la región Costa de Oaxaca, México, para conocer los factores y agentes bióticos relacionados con esta especie. La mortalidad y sanidad de las plantas se registró durante 18 meses, y se determinaron diferencias entre sitios y procedencias. Orthogeomys grandis (tuza) en Pinotepa de Don Luis (27.9 %) y la sequía (29.2 %) en Valdeflores causaron mayor mortalidad de individuos. Cenicilla (Oidum), pulgón (Aphis), cochinilla algodonosa (Pseudoccocus longispinus), corta palos (Oncideres), un barrenador (Lepidoptera) y un defoliador (Lepidoptera) se vincularon con la sanidad de E. cyclocarpum. Las cenicillas y los pulgones afectaron el mayor número de ejemplares; en Pinotepa de Don Luis, las cenicillas infectaron 58.8 % de las plantas y los pulgones a 29.2 %; mientras que, en Valdeflores la afectación fue de 3.3 % y 0.8 %, respectivamente. En Pinotepa de Don Luis, Cortijo y Colotepec tuvieron menor infección de cenicilla y la infestación de pulgones no fue significativa entre las procedencias. En Valdeflores, cinco procedencias carecieron de presencia de cenicilla y, únicamente, El Zarzal tuvo evidencia de pulgones. La ubicación y la precipitación de los sitios influyeron en los niveles de mortalidad y sanidad de las plantas de E. cyclocarpum.

Palabras clave Aphis; Oidium; Oncideres; plantaciones tropicales; Pseudococcus longispinus (Targioni Tozzetti; 1867); sequía

Introduction

In Mexico, 4.708 million ha of forest have been planted for commercial and conservation purposes between years 2000 and 2018; however, their survival rate is 20 to 64 % (GEUM, 2018). This rate is similar in experimental plantations, ranging between 22 and 82 % (Pedraza and Williams-Linera, 2003; Alvarez-Aquino et al., 2004; Muñoz et al., 2013; Sigala et al., 2015). This low survival is due to a number of factors, including the quality of the plant, the production systems and the provenance of the seeds (Ramírez-Contreras and Rodríguez-Trejo, 2004; Rodríguez-Trejo, 2006; Sigala et al., 2015), as well as to the conditions of the plantation site, predation, pests and diseases (Alvarez-Aquino et al., 2004; Ramírez-Contreras and Rodríguez-Trejo, 2004; Cibrián, 2013).

Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. is a multipurpose tree (Couttolenc-Brenis et al., 2005) of significant forestry importance. It is native of Mexico and Central America (Vázquez-Yanes et al., 1999; Pennington and Sarukhán, 2005). In tropical zones of Mexico, it is used for restoration programs, agroforestry and silvopastoral systems and commercial forest plantations (Vázquez-Yanes et al., 1999; Muñoz-Flores et al., 2016). Nevertheless, the survival rate ranges between 50.8 and 64 % (Foroughbakhch et al., 2006; Muñoz et al., 2013), although the causes of mortality in these plantations are unknown, they may be assumed to be related to the provenance of the seeds, and plantation site (Foroughbakhch et al., 2006; Muñoz et al., 2013) and to pests and diseases (Cibrián, 2013).

In Mexico, there is a huge gap in the knowledge on the predation and the biotic agents related to the health of E. cyclocarpum in forest plantations. However, these delay the growth, affect the productivity and may cause the death of the trees (Cibrián, 2013). As for the health of E. cyclocarpum, insects of the Aphis genus, the citrus mealy bug, and the pink mealy bug have been found to affect the shoots, leaves, branches and fruits of adult individuals across the country (Solares, 2008; López-Arriaga et al., 2010; Sinavef, 2011; Isiordia-Aquino et al., 2012). Furthermore, three bark beetle species, including Xyleborus volvulus (F.), damage the tree stem (Cibrián et al., 1995; Solares, 2008).

On the other hand, knowledge of the geographic adaptive variation allows the creation of movement rules of forest seeds (Zobel and Talbert, 1988; White et al., 2007), which increase the likelihood of success of the plantations. It is essential to choose the adequate provenance for each particular site, in order to reduce the mortality, increase the productivity and improve the health of the planted trees (White et al., 2007). For this reason, provenance assays are necessary to select plants that are resistant to predation and biotic agents associated with to health (Zobel and Talbert, 1988; White et al., 2007).

Within this context, an assay of the provenances of E. cyclocarpum was performed in two sites of the region of the Coast of Oaxaca, Mexico, with the following purposes: 1) to determine the mortality factors and to assess the percentage of dead plants in provenances of E. cyclocarpum; 2) to identify biotic agents related to health and to evaluate the affectation percentage in provenances of E. cyclocarpum. The proposed hypothesis was that the ecological conditions of the plantation sites may favor or affect the mortality and health of the provenances of E. cyclocarpum.

Materials and Methods

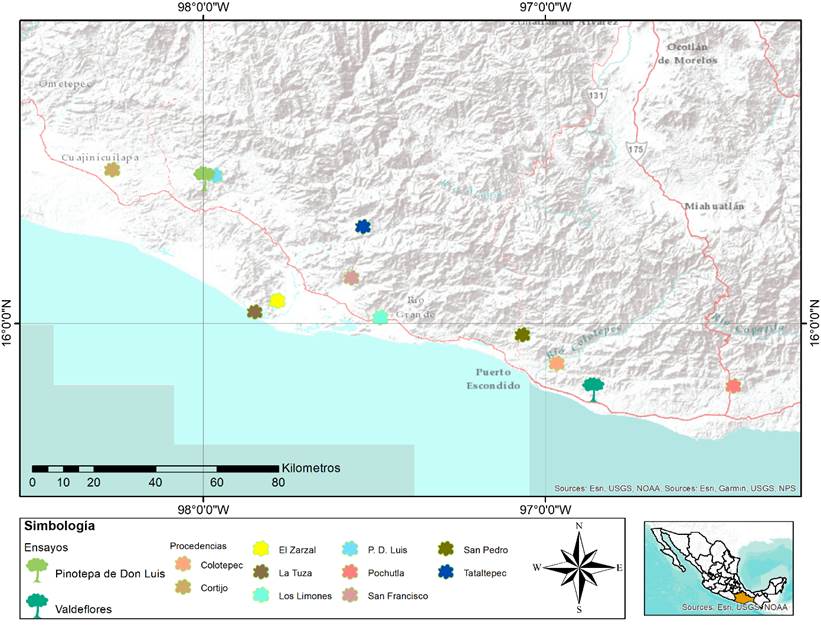

A provenance assay of E. cyclocarpum was established at two sites in the Coast of Oaxaca region (Figure 1, Table 1). The seeds from 10 provenances were collected between March and May 2008 in the coast of Oaxaca. The germination and production of plants took place on a substrate constituted by 35 % soil, 35 % bark, and 305 sawdust. The age of the plants was six months, and the average height at the time of the planting, in June 2009 in Valdeflores, and in July 2009 in Pinotepa de Don Luis, was 25 cm. The nearest provenance to the first locality was Colotepec, and the second provenance was local. In both, the experimental design consisted of randomized complete blocks with 10 treatments (provenances), six replications and four plants per experimental unit.

Figure 1 Spatial distribution of the provenances of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. and geographic location of the assay sites in the Coast of Oaxaca.

Table 1 Characteristics of the sites and provenances of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. evaluated in the Coast of Oaxaca region.

| Altitude (m) | MAT (°C) | MAP (mm) | AI | ST | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sites | |||||

| Pinotepa de Don Luis | 455 | 25.9 | 1645 | 4.6 | Regosol |

| Valdeflores | 90 | 25.8 | 910 | 8.2 | Phaeozem |

| Provenances | |||||

| Cortijo | 59 | 26.9 | 1176 | 6.7 | Luvisol |

| Pinotepa de Don Luis | 420 | 26.1 | 1658 | 4.6 | Regosol |

| El Zarzal | 14 | 26.8 | 1194 | 6.6 | Phaeozem |

| La Tuza | 15 | 26.8 | 1185 | 6.6 | Regosol |

| Tataltepec | 370 | 26.5 | 1296 | 6.0 | Regosol |

| San Francisco | 67 | 26.9 | 1215 | 6.5 | Phaeozem |

| Los Limones | 23 | 26.9 | 1197 | 6.6 | Phaeozem |

| San Pedro | 240 | 25.9 | 1102 | 6.8 | Phaeozem |

| Colotepec | 37 | 26.3 | 938 | 8.2 | Cambisol |

| Pochutla | 234 | 25.4 | 1331 | 5.5 | Cambisol |

MAT = Mean annual temperature; MAP = Mean annual precipitation; AI = Aridity index, provided by the Moscow Forestry Science Laboratory (Crookston, 2018); ST = Soil type (INEGI, 2013).

The plantation was inspected fortnightly during the first 18 months; the cause of mortality and the biotic agents present (pests or pathogenic organisms) present in the plants were recorded in each visit. At the end of the period, the mortality rate and the number of infected and infested individuals was estimated. These were identified (by class, family, genus or species) by comparing the specimen and its damage with the information cited in books, manuals, brochures, data sheets and specialized taxonomic codes (Cibrián et al., 1995; Cibrián et al., 2007a; Solares, 2008; Barriga, 2009; Monné and Bezark, 2011; Cibrián, 2013); in addition, specialists in certain taxonomic groups were consulted.

The assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances of the data were verified with the Shapiro-Wilks test and Levene’s test, respectively. Neither variable met any of the two assumptions; therefore, the differences between sites and between provenances in each site were determined by means of a variance analysis and RT-3 multiple range RT-3 comparisons (Conover, 2012).

Results and Discussion

Mortality

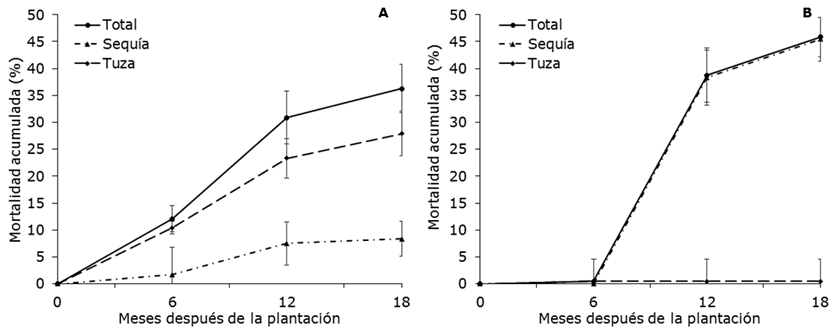

In both plantations, drought and gophers were the main factors that caused the largest plant mortality percentages. The symptoms of death by drought were curling of the leaflets, followed by withering and death of young leaves and, subsequently, by downward withering and death of the adult leaves and stem; the roots exhibited no damage due to predation. The individuals killed by gophers exhibited gnawed roots and the presence of gopher tunnel entrances at the base of the plant stems. The identified species was Orthogeomys grandis (Thomas, 1893), which is widely distributed in the Coast of Oaxaca (Lira et al., 2005). Total mortality rates increased during the evaluation period (Figure 2), and there were significant differences between sites (p= 0.03312); mortality due to drought (p˂ 0.0001) and to gophers (p˂ 0.0001) also increased. In both Pinotepa de Don Luis and Valdeflores, the total mortality rate was 38.3 and 45.8 %; mortality due to drought was 8.3 and 29.2 %, and mortality due to gophers, 27.9 y 0.4 %, respectively (Figure 2).

Mortalidad acumulada = Accumulated mortality; Meses después de la plantación = Months after planting.

Figure 2 Mortality (total, due to droughts and to gophers) of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. accumulated in three periods (6, 12 and 18 months) in Pinotepa de Don Luis (A) and Valdeflores (B), in the Coast of Oaxaca region.

The mortality factors were differentiated between plantation sites: drought was the main cause of mortality in Valdeflores, and attack by gophers, in Pinotepa de Don Luis. The difference in mortality rates due to drought between the sites was rain-related: the mean annual precipitation in Valdeflores (910 mm) was lower than that registered in Pinotepa de Don Luis (1 645 mm), while the aridity index (AI) in Valdeflores (8.2) was higher than that of Pinotepa de Don Luis (4.6). In the latter locality, predation by gophers was greater, due, perhaps, to the fact that, during the first six months, the plantation was mixed with corn crops, which may have induced a greater damage because corn is food for the gophers. Viveros-Viveros et al. (2005) cited mortality caused by gophers in a Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. assay in which the population of this rodent increased in response to the agricultural history of the site, the availability of food, and the elimination of its natural predators. Furthermore, the soils of Pinotepa de Don Luis are silty and deep, which facilitates the digging of burrows by this mammal; on the other hand, in Valdeflores the soil is clayey and shallow (INEGI, 2013).

The total mortality was significantly different (p≤ 0.0355) between provenances at both sites. In Pinotepa de Don Luis, the plants from the San Pedro provenance had a lower total mortality and those from Colotepec had the highest; likewise, the plants from San Pedro and Pochutla were less affected by the gophers, and those from Cortijo were most affected. On the other hand, individuals from four provenances showed more tolerance to drought (Table 2). In Valdeflores, plants from the Cortijo and Tataltepec provenances had a lower total mortality and exhibited a higher tolerance to drought, unlike those of San Francisco, which had the highest total mortality rate and less tolerance to drought (Table 2).

Table 2 Percentage and mean comparison of mortality rates between Enterolobium cyclocarpum provenances in Pinotepa de Don Luis and Valdeflores, in the Coast of Oaxaca region.

| Provenances | Pinotepa de Don Luis | Valdeflores | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Drought | Gophers | Total | Drought | Gophers | |

| Cortijo | 50.0cd | 8.3ab | 41.7b | 29.2a | 29.2ab | 0.0a |

| Pinotepa de Don Luis | 29.2abcd | 4.2a | 25.0ab | 50.0abc | 50.0abcd | 0.0a |

| El Zarzal | 37.5abcd | 4.2a | 33.3ab | 37.5ab | 37.5abc | 0.0a |

| La Tuza | 45.8bcd | 8.3ab | 37.5ab | 45.8abc | 45.8abcd | 0.0a |

| Tataltepec | 41.7abcd | 12.5ab | 29.2ab | 29.2a | 25.0a | 4.2b |

| San Francisco | 41.7abcd | 4.2a | 37.5ab | 66.7c | 66.7d | 0.0a |

| Los Limones | 25.0abc | 8.3ab | 16.7ab | 54.2abc | 54.2bcd | 0.0a |

| San Pedro | 16.7a | 4.2a | 12.5a | 37.5ab | 37.5abc | 0.0a |

| Colotepec | 54.2d | 20.8b | 33.3ab | 45.8abc | 45.8abcd | 0.0a |

| Pochutla | 20.8ab | 8.3ab | 12.5a | 62.5bc | 62.5bcd | 0.0a |

Values with different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p≤ 0.0389).

In Pinotepa de Don Luis, the plants produced with seeds from the same locality evidenced a higher tolerance to drought, which proved that the local provenance is better adapted. However, the specimens from San Pedro were tolerant to drought and to predation by gophers. This response may be due to the fact that it is one of the provenances with a similar altitude to that of the plantation site and a high AI (6.8); thus, it is a better location for planting than Pinotepa de Don Luis, which is more humid (AI= 4.6). In Valdeflores, the Colotepec provenance was the closest to the plantation site and had the same AI as this (8.2); therefore, it was expected to have the lowest plant mortality rate. Nevertheless, it exhibited an intermediate value, which is statistically equal to all the provenances. The result for Colotepec in Valdeflores may have been due to the difference in the soil type, which is Cambisol in Colotepec and Phaeozem at the site of establishment (Inegi, 2013).

Health

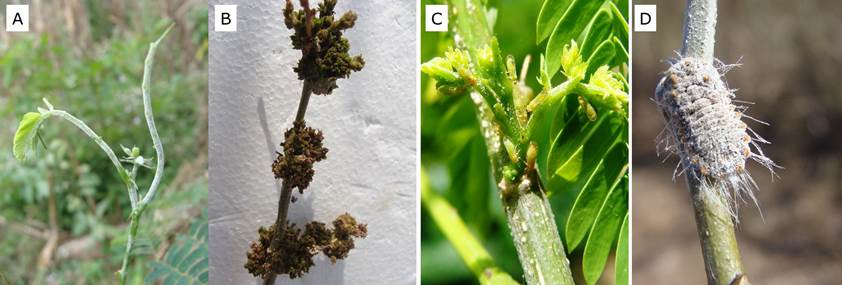

Six biotic agents related to the health of E. cyclocarpum were identified (Table 3, figures 3 and 4) during the assessment period; of these, powdery mildew of the genus Oidium Link and aphids (Aphis L.) were more prevalent on the assay plants. In Mexico, there are few records of attack by powdery mildew in forest species, particularly in tropical ones. Robles (2010) refers to cases of infection by Oidium sp. in nursery-grown E. cyclocarpum saplings. García and Cibrián (2007) cite infections in nursery-grown Acacia spp., Erythrina spp. and Quercus spp. saplings, while Cibrián et al. (2007b) document infection by powdery mildew (Podosphara Kunze, Micrisphaera Lév. and Phyllactina Lév.) in adult Acacia spp., Fraxinus spp., Quercus spp., Ulmus spp., Acer negundo L., Erythrina coralloides DC. and Platanus occidentalis L. plants.

Table 3 Biotic agents associated to health and description of damages in Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. provenances of the Coast of Oaxaca.

| Biotic agent | Description of the damage |

|---|---|

| Powdery mildew: Oidium sp. (Erysiphales: Erysiphaceae) | The apical buds and tender stems were affected: a white powder was observed (Figure 3A). The main stem stopped growing, and multiple buds emerged (Figure 3B). |

| Aphid: Aphis sp. (Homoptera: Aphididae) | These insects sucked the sap of apical buds, shoots and tender leaves, causing a yellowing and the growth in height was stalled (Figure 3C). |

| Long-tailed mealybug: Pseudoccocus longispinus (Targioni Tozzetti, 1867) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) | The shoots and apical buds were affected: the insect sucked the sap and thereby limited the growth in height (Figura 3D). |

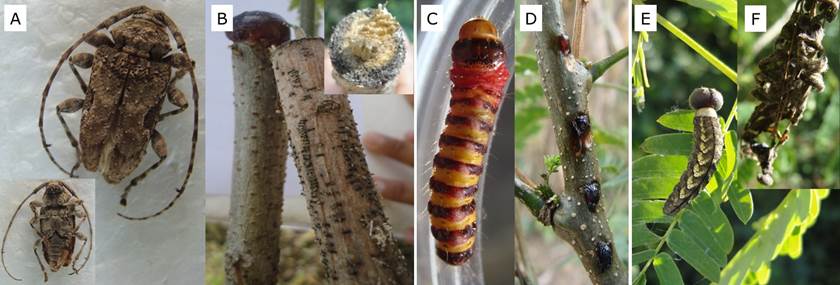

| Longhorn beetles: Oncideres sp. (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) | This insect attacked the stem and the main branches: it made a (spiraling) circular cut that caused the toppling of the upper part of the spiral. The standing stem (below the cut) produced new shoots, and forking occurred (Figure 4A, 4B). |

| Bark beetle: (Lepidoptera) | This insect attacked the main stem: the larvae drilled the pith; first, a borehole was observed close to the apical bud (which died); subsequently, several lumps of sap oozed from the stem (Figure 4C, 4D). |

| Defoliator: (Lepidoptera) | This insect attacked young leaves: the larvae (Figure 4E) fed on these and produced silk, with which they surrounded the branches, causing their death (Figure 4F). |

Figure 3 Powdery mildew of the genus Oidium (A) and its effect (B), aphids of the Aphis genus (C) and Pseudoccocus longispinus (Targioni Tozzetti, 1867) (D) in provenances of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. in the Coast of Oaxaca.

Figure 4 Longhorn beetle of the genus Oncideres (A), larva of the stem bark beetle (C) and larva of the defoliator insect (E), and their respective damages (B, D, F) in Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. provenances of the Coast of Oaxaca.

In Mexico, aphids of the genus Aphis damage the rachis of the leaves and tender stems of nursery-grown E. cyclocarpum saplings and adult plants (Solares, 2008; Robles, 2010); in Venezuela, Aphis spiraecola Pach affects adult plants of the same species (Evelin and Marcos-García, 2004). In Mexico City and in the State of Mexico, Aphis nerii Boyer de Fonscolombe aphids damage Nerium oleander L. leaves (Cibrián et al., 1995). In other countries, like Costa Rica, Cuba, Colombia and Venezuela, Aphis sp. attacks Eucalyptus deglupta Blume (Arguedas, 2008), A. gossypii Glover affects Tectona grandis L. Fil, A. spiraecola Patch damages Cordia alliodora (Ruiz & Pav.) (Cibrián, 2013), and A. craccivora Coch affects Gliricidia sepium (Jacq.) Steud and Cordia alba (Jacq.) Roem & Schult (Evelin and Marcos-García, 2004).

The occurrence of Oidium sp. and Aphis sp. was significantly different between sites (p˂ 0.0001). In Pinotepa de Don Luis, an average of 58.8 % and 29.2 % of the plants exhibited infection by Oidium and Aphis, respectively, while in Valdeflores the average percentages were 3.3 % and 0.8 %. This may be due to the difference in location and precipitation of the sites. Pinotepa de Don Luis is located at a higher altitude, and there is a greater precipitation in this site than in Valdeflores (Table 1). Accordingly, the risk of attack by Oidium mangiferae Berthet increases with the altitude of the sites (Arias et al., 2004). Furthermore, infection by the fungus Cercospora coffeicola Berk & Cooke is related to high precipitation (Montes et al., 2012).

In each of the plantations, the incidence of Oidium sp. was significantly different between provenances (p≤ 0.0389). In Pinotepa de Don Luis, the Cortijo and Colotepec provenances had a lower percentage of plants infected by Oidium sp. (41.7 %); conversely, Los Limones registered a higher percentage of infection (70.8 %) (Table 3). In Valdeflores, the Cortijo, El Zarzal, La Tuza, Tataltepec and San Francisco provenances exhibited infection (4.2 to 8.3 %), while the others had none. Since the provenances Cortijo, El Zarzal and La Tuza showed lower percentages of infection by Oidium sp. in Pinotepa de Don Luis, no infection was expected to be found in Valdeflores; however, the opposite was the case, due to the genotype x environment interaction (p= 0.049) in the occurrence of Oidium sp. on E. cyclocarpum.

As for the occurrence of Aphis, there were no significant differences between the provenances in Pinotepa de Don Luis (p= 0.0603); conversely, such differences were found in Valdeflores (p= 0.0012), but the effect of the genotype X environment interaction was not significant (p= 0.5300). In Pinotepa de Don Luis, infection by Aphis varied from 16.7 to 41.7 % between provenances. However, in Valdeflores only 8.3 % of the plants of El Zarzal exhibited infection (Table 4).

Table 4 Percentage and comparison of measures of plants affected by two biotic agents related to the health of the provenances of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb., in the Coast of Oaxaca.

| Provenances | Pinotepa de Don Luis | Valdeflores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oidium | Aphis | Oidium | Aphis | |

| Cortijo | 41.7a | 20.8a | 8.3ab | 0.0a |

| Pinotepa de Don Luis | 62.5ab | 33.3a | 0.0a | 0.0a |

| El Zarzal | 54.2ab | 41.7a | 4.2ab | 8.3b |

| La Tuza | 54.2ab | 25.0a | 4.2ab | 0.0a |

| Tataltepec | 62.5ab | 25.0a | 12.5b | 0.0a |

| San Francisco | 58.3ab | 29.2a | 4.2ab | 0.0a |

| Los Limones | 70.8b | 41.7a | 0.0a | 0.0a |

| San Pedro | 70.8b | 16.7a | 0.0a | 0.0a |

| Colotepec | 41.7a | 20.8a | 0.0a | 0.0a |

| Pochutla | 70.8b | 37.5a | 0.0a | 0.0a |

Values with different letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p≤ 0.0389).

The difference between the occurrence of Oidium sp. and that of Aphis sp. in E. cyclocarpum allows selecting of adequate provenances for each plantation site. However, the existence of the genotype x environment interaction in young plants hinders their early selection for various sites. Nevertheless, the instability of certain characteristics in different environments is usual in trees or in wild provenances (Salaya-Domínguez et al., 2012). On the other hand, subsequent assessments are required, as the effect of the interaction may vary according to age (Salaya-Domínguez et al., 2012).

During the study period, powdery mildew affected only three plants in Pinotepa de Don Luis. In Mexico, these insects are documented to affect the leaves and stems of adult E. cyclocarpum trees, causing yellowing, reduced growth, and branch death (Solares, 2008). Likewise, the pink mealy bug (Maconellicoccus hirsutus (Green)) also causes malformation in E. cyclocarpum shoots, leaves, branches and fruits (López-Arriaga et al., 2010; Sinavef, 2011; Isiordia-Aquino et al., 2012). There are no records of attack by powdery mildew in other forest species; only the pink mealy bug has been documented in Tectona grandis, Artocarpus hererophyllus Lam. and Acacia spp. (Sinavef, 2011).

In Mexico, 20 species of the Oncideres Lacordaire genus have been registered (Monné and Bezark, 2011), which are in the habit of forming rings around adult tree branches or trunks of young specimens in order to deposit their eggs (Villaverde and Acosta, 2013), as was observed in one and three E. cyclocarpum plants in Valdeflores and Pinotepa de Don Luis, respectively. Although the presence of Oncideres species, which no attack of E. cyclocarpum was observed in Huatulco (in the Coast of Oaxaca region), the occurrence of Oncideres pallifasciata Noguera (Noguera et al., 2018) has been registered at a linear distance of 108 and 57 km from Pinotepa de Don Luis and Valdeflores, respectively. However, there is no documentary evidence of infestation by Oncideres spp. in E. cyclocarpum plants; therefore, this study is the first record of its occurrence. Notably, in Costa Rica, Oncideres punctata Dillon & Dillon causes the same damage in E. cyclocarpum trunks (Hilje and Arguedas, 1996).

The presence of Oncideres ocellaris Bates, O. scitula Bates; O. senilis Bates and O. albomarginata chamela (Noguera, 1993; Toledo et al., 2007; MacRae et al., 2012; Nearns et al., 2014) is cited in Oaxaca, Mexico. The third of these species affects Amphipterygium adstringens Schide ex Schlecht, Bursera Jacq. ex L. spp. y Ceiba pentandra (L.) Gaertn trees (Calderón-Cortés et al., 2011). In Tamaulipas, Mexico, O. pustulata LeConte is hosted by Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. and Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit plants (Rodríguez-del-Bosque and Garza-Cedillo, 2008; Rodríguez-del-Bosque, 2013). In the Desert of Chihuahua, Mexico, O. rhodosticta attacks Prosopis glandulosa var. torreyana (L. Benson) M.C. Johnston (Martínez et al., 2009), while, in Nuevo León and Tamaulipas, Mexico, O. cingulata texana Horn and O. pustulatus infest specimens of Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd., Acacia spp., Citrus spp., Leucaena spp., Pithecellobium spp. and Prosopis spp. (Cibrián et al., 1995).

The stem bark beetle of E. cyclocarpum (Lepidoptera) affected 22 plants in Pinotepa de Don Luis, and five in Valdeflores. Although this species was not identified due to a lack of adult specimens, this is the first record of damage by a bark beetle in young E. cyclocarpum plants in Mexico. On the other hand, an unidentified bark beetle that bores superficial galleries in the stems and another one that bores numerous galleries damaging the vascular cambium, the xylem and the phloem (Solares, 2008) were observed in adult trees. Xyleborus volvulus (F.) (Coleoptera) forms galleries at various levels of the tree trunk (Cibrián et al., 1995). The damage caused by X. volvulus (Cibrián et al., 1995) and by the bark beetles mentioned by Solares (2018) do not correspond with the damage observed in the present study, in which the main shoot is the affected part (Table 3, Figure 4C and 4D).

At both plantation sites, a defoliator insect of the Lepidoptera order was observed in four E. cyclocarpum plants. In Mexico, there are no records of defoliator insects in E. cyclocarpum; therefor, the present study is the first record of the present of these insects; however, more studies are required in order to be able to identify the species, its life cycle, and its effect on E. cyclocarpum plants. Coenipita bibitrix Huebner (Noctunidae), Mocis latipes Guenée (Noctunidae), Hylesia lineata (Saturniidae), and an unidentified species of the family Meloidae are known to defoliate E. cyclocarpum plants in Costa Rica (Janzen, 1981; Arguedas, 2008).

Conclusions

Drought and damage caused by pocket gophers are the main causes of mortality in E. cyclocarpum plants. The two mortality factors affect the plants differently; this has to do with the humidity level and with the soil type of the plantation sites. The six health-related agents described constitute the first record in Mexico of damage in young E. cyclocarpum plants. The difference between sites in the occurrence of Oidium and Aphis are related to the location of the plantation sites and to the precipitation levels in each of them.

The existence of an interaction between the genotype and the environment renders the selection of tolerant provenance for all the plantation sites difficult. However, the differential response of the various provenances to the mortality factors and biotic agents related to the health of E. cyclocarpum allows selecting adequate provenances for each plantation site.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to René Robles Silva for the collection of seeds, and to Rolando Galán Larrea and Justino Ríos Altamirano for providing the plots for the assays.

REFERENCES

Alvarez-Aquino, C., G. Williams-Linera and A. C. Newton. 2004. Experimental native tree seedling establishment for the restoration of a Mexican cloud forest. Restoration Ecology 12(3): 412-418. [ Links ]

Arguedas G., M. 2008. Plagas y enfermedades forestales en Costa Rica. Ed. Corporación Garro y Moya. San José, Costa Rica. 68 p. [ Links ]

Arias S., J. F., J. Espinoza A., H. R. Rico P. y M. A. Miranda S. 2004. La cenicilla Oidium mangiferae Berthet del mango en Michoacán. INIFAP, CIRPAC. Campo Experimental Valle de Apatzingán. Folleto Técnico Núm. 1. Apatzingán, Mich., México. 24 p. [ Links ]

Barriga T., J. E. 2009. Coleoptrera Neotropical. http://www.coleoptera-neotropical.org/paginaprincipalhome.html (14 de agosto de 2018). [ Links ]

Calderón-Cortés, N., M. Quesada and L. H. Escalera-Vázquez. 2011. Insects as stem engineers: interactions mediated by the twig-girdler Oncideres albomarginata chamela enhance arthropod diversity. PLoS ONE 6(4): e19083. [ Links ]

Cibrián T., D. 2013. Manual para la identificación y manejo de plagas de plagas en plantaciones forestales comerciales. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. 229 p. [ Links ]

Cibrián T., D., D. Alvarado R. y S. E. García D. 2007a. Enfermedades Forestales de México. UACH, CONAFOR-SEMARNAT, FS-USDA, NRCAN-FS, COFAN-FAO. Chapingo, Edo. de Méx., México. 453 p. [ Links ]

Cibrián T., D. , J. T. Méndez M., R. Campos B., H. O. Yates y J. Flores L. 1995. Insectos Forestales de México. DCF-UACH, SFFS-DSF, FS-USDA, FS-NRCAN. Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. 453 p. [ Links ]

Cibrián T., D. , S. E. García D. y D. Alvarado R. 2007b. Cenicillas polvorientas de latifoliadas. Podosphara Kunze, Micrisphaera Lév. y Phyllactina Lév. (Erisiphales, Erisiphaceae). In: Cibrián T., D. , D. Alvarado R. y S. E. García D. (eds.). Enfermedades Forestales de México. UACH, Conafor-Semarnat, FS-USDA, FS-NRCAN, Cofan-FAO. Chapingo, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 132-134. [ Links ]

Conover, W. J. 2012. The rank transformation-an easy and intuitive way to connect many nonparametric methods to their parametric counterparts for seamless teaching introductory statistics courses. Computational Statistics 4(5): 432-438. [ Links ]

Couttolenc-Brenis, E., J. A. Cruz-Rodríguez, E. Cedillo-Portugal y M. A. Musálem. 2005. Uso local y potencial de las especies arbóreas en Camarón de Tejeda, Veracruz. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 11(1): 45-50. [ Links ]

Crookston, N. 2018. Research on forest climate change: potential effects of global warming on forests and plant climate relationships in western North America and Mexico. http://forest.moscowfsl.wsu.edu/climate/customData/ (9 de mayo de 2018). [ Links ]

Evelin A., F. D. y A. A. Marcos-García. 2004. Nuevos áfidos presa de Pseudodoros clavatus (Fabricius, 1794) (Diptera, Syrphidae) potencial agente de control biológico. Boletín de la Sociedad Española de Entomología 28 (1-2): 245-249. [ Links ]

Foroughbakhch, R., M. A. Alvarado-Vázquez, J. L. Hernández-Piñero, A. Rocha-Estrada, M. A. Guzmán-Lucio and E. J. Treviño-Garza. 2006. Establishment, growth and biomass production of 10 tree woody species introduced for reforestation and ecological restoration in northeastern Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 235: 194-201. DOI :10.1016/j.foreco.2006.08.012 [ Links ]

García D., S. E. y D. Cibrián T. 2007. Cenicillas polvorientas. Oidium Link (Moniliales, Moniliaceae). In: Cibrián T., D. , D. Alvarado R. y S. E. García D. (eds.). Enfermedades Forestales de México. UACH, CONAFOR-SEMARNAT, FS-USDA, NRCAN-FS, COFAN-FAO. Chapingo, Edo. de Méx., México. pp:522-523. [ Links ]

Gobierno de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (GEUM). 2018. Sexto Informe de Gobierno 2017-2018. Presidencia de la República. Ciudad de México, México. 873 p. [ Links ]

Hilje, L. and M. Arguedas. 1996. Pests of important nitrogen fixing trees that tolerate acid soil. In: Powell, M. H. (ed.). Nitrogen Fixing trees for acid soils. Winrock International. Morrilton, AR, USA. pp: 58-71. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística (INEGI). 2013. Mapa Digital de México: Suelos 1:250000 (2002-2007). http://gaia.inegi.org.mx/mdm6/?v=bGF0OjE2LjI0MTkwLGxvbjotOTYuMDcxNDcsejo1LGw6YzQxNg== (8 de octubre de 2018). [ Links ]

Isiordia-Aquino, N., A. Robles-Bermúdez, O. García-Martínez, R. Lomelí-Flores, R. Flores-Canales, J. R. Gómez-Aguilar y R. Espino-Alvarez. 2012. Especies forestales y arbustivas asociadas a Maconellicoccus hirsutus (Green) (Hemiptera: Pseudococcidae) en el norte de Nayarit, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 28(2): 414-426. [ Links ]

Janzen, D. H. 1981. Patterns of Herbivory in a Tropical Deciduous Forest. Biotropica 13(4): 271-282. [ Links ]

Lira T., I., L. Mora A., M. A. Camacho E. y R. E. Galindo A. 2005. Mastofauna del Cerro de La Tuza, Oaxaca. Revista Mexicana de Mastozoología 9:6-20. [ Links ]

López-Arriaga, J. G., M. A. Urias-López y L. M. Hernández-Fuentes. 2010. Manual técnico para la Identificación y control de la cochinilla rosada del hibisco. Folleto Técnico Núm. 15. INIFAP, Campo Experimental Santiago Ixcuintla. Nayarit, México.65 p. [ Links ]

MacRae, T. D., L. G. Bezark and I. Swift. 2012. Notes on distribution and host plants of Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) from southern Mexico. The Pan-Pacific Entomologist 88(2): 173-187. [ Links ]

Martínez, A. J., J. López-Portillo, A. Eben and J. Golubov. 2009. Cerambycid girdling and water stress modify mesquite architecture and reproduction. Population Ecology 51:533-541. [ Links ]

Monné, M. A. and L. G. Bezark. 2011. Checklist of the Cerambycidae and related families (Coleoptera) of the Western Hemisphere 2011 Version. http://plant.cdfa.ca.gov/byciddb/checklists/WestHemiCerambycidae2011.pdf (14 de agosto de 2018). [ Links ]

Montes R., C., O Armando P. y R. Amilcar C. 2012. Infestación e incidencia de broca, roya y mancha de hierro en cultivo de café del Departamento del Cauca. Biotecnología en el Sector Agropecuario y Agroindustrial 10(1): 98-108. [ Links ]

Muñoz F., H. J., J. J. García M., G. Orozco G., V. M. Coria Á. y M. B. Nájera-Rincón. 2013. Evaluación de una plantación con dos especies tropicales cultivadas en diferentes tipos de envases. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 4(18): 28-43. [ Links ]

Muñoz-Flores H. J., J. T. Sáenz-Reyes, A. Rueda-Sánchez, D. Castillo-Quiroz, F. Castillo-Reyes, D. Y. Avila-Flores. 2016. Areas with Potential for Commercial Timber Plantations of Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jacq.) Griseb. in Michoacán, México. Open Journal of Forestry 6(5): 476-485. [ Links ]

Nearns, E. H., M. V. L. Barclay and G. L. Tavakilian. 2014. Onciderini Thomson, 1860 (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae: Lamiinae) types of The Natural History Museum (BMNH). Zootaxa 3857(2): 261-274. [ Links ]

Noguera, F. A. 1993. Revisión taxonómica del género Oncideres Serville en México (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). Folia Entomológica Mexicana 88: 9-60. [ Links ]

Noguera, F. A., M. A. Ortega-Huerta, S. Zaragoza-Caballero, E. González-Soriano and E. Ramírez-García. 2018. Species richness and abundance of Cerambycidae (Coleoptera) in Huatulco, Oaxaca, Mexico; relationships with phenological changes in the tropical dry forest. Neotropical Entomology 47: 457-469. [ Links ]

Pedraza, R. A. and G. Williams-Linera. 2003. Evaluation of native tree species for the rehabilitation of deforested areas in a Mexican cloud forest. New Forests 26: 83-99. [ Links ]

Pennington, T. D. y J. Sarukhán. 2005. Árboles tropicales de México. Manual para la identificación de las principales especies. UNAM. México, D.F., México. 523 p. [ Links ]

Ramírez-Contreras, A. y D. A. Rodríguez-Trejo. 2004. Efecto de calidad de planta, exposición y micrositio en una plantación de Quercus rugosa. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 10(1): 5-11. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-del-Bosque, L. A. 2013. Feeding and Survival of Oncideres pustulata (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) Adults on Acacia farnesiana and Leucaena leucocephala (Fabaceae). Southwestern Entomologist 38(3): 487-498. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-del-Bosque, L. A . and R. D. Garza-Cedillo. 2008. Survival, emergence, and damage by Oncideres pustulata (Coleoptera: Cerambycidae) on huisache and leucaena (Fabaceae) in Mexico. Southwestern Entomologist 33(3): 209-217. [ Links ]

Rodríguez-Trejo, D. A. 2006. Notas sobre el diseño de plantaciones de restauración. Revista Chapingo Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 12(2): 111-123. [ Links ]

Salaya-Domínguez J. M., J. López-Upton y J. J. Vargas-Hernández. 2012. Variación genética y ambiental en dos ensayos de progenies de Pinus patula. Agrociencia 46(5): 519-534. [ Links ]

Sigala R., J. A., M. A. González T. y J. A. Prieto R. 2015. Supervivencia en plantaciones de Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. en función del sistema de producción y preacondicionamiento en vivero. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 6(30): 20-31. [ Links ]

Sistema Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica Fitosanitaria (Sinavef). 2011. Reporte epidemiológico: cochinilla Rosada del hibisco. SAGARPA, SENASICA, UASLP. San Luis Potosí, México. 15 p. [ Links ]

Solares A., F. 2008. Diagnóstico de los problemas fitosanitarios del árbol histórico de la Parota (Enterolobium cyclocarpum (Jaq.) Griseb.) de la plaza central de la Ciudad de Ayala, Morelos. Folleto Técnico Número 24. INIFAP. Campo Experimental Zacatepec, Morelos, México. 12 p. [ Links ]

Toledo, V. H., A. M. Corona and J. J. Morrone. 2007. Track analysis of the Mexican species of Cerambycidae (Insecta, Coleoptera). Revista Brasileira de Entomologia 51(2): 131-137. [ Links ]

Vázquez-Yanes, C., A. I. Batis M., M. I. Alcocer S., M. Gual D. y C. Sánchez D. 1999. Árboles y arbustos potencialmente valiosos para la restauración ecológica y la reforestación. CONABIO, Instituto de Ecología, UNAM. México D. F., México. 262 p. [ Links ]

Villaverde, R. y N. Acosta. 2013. Oncideres spp. “Corta palos”, “Serrucho”. Ficha Técnica-Sanidad Forestal, Plagas no. 4. MAGyP- Dirección de Producción Forestal, Área de Sanidad Forestal. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 7 p. [ Links ]

Viveros-Viveros, H., C. Sáenz-Romero, J. López-Upton y J. J. Vargas-Hernández. 2005. Variación genética altitudinal en el crecimiento de plantas de Pinus pseudostrobus Lindl. en campo. Agrociencia 39: 575-587. [ Links ]

White, T. L., W. M. Adams and D. B. Neale. 2007. Forest Genetic. CAB International. Cambridge, MA USA. 682 p. [ Links ]

Zobel, B. y J. Talbert. 1988. Técnicas de mejoramiento genético de árboles forestales. Limusa. México, D.F., México. 545 p. [ Links ]

Received: November 22, 2018; Accepted: April 02, 2019

texto en

texto en