Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.10 no.56 México Nov./Dez. 2019 Epub 30--2020

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i56.454

Scientific article

Phytophagous mites and insects in the Recreational and Cultural Tezozómoc park trees, Azcapotzalco, Mexico City

1Laboratorio de Control de Plagas, Unidad de Morfología y Función, Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México.

2Laboratorio de Entomología y Fitopatología Forestal, Centro Nacional de Investigación Disciplinaria en Conservación y Mejoramiento de Ecosistemas Forestales, INIFAP. México.

Urban and suburban trees are essential elements in the character of populated areas as they have the capacity to transform cities, providing environmental, aesthetic, cultural and economic benefits. In Mexico City, Tezozomoc Park is very important for the neighbors in the northern area because it has an artificial central lake surrounded by abundant vegetation. However, its trees have been damaged by different, which led to in this study, in which phytophagous insects and mites were detected and determined. For the diagnosis, 10 % of the total frequency of the dominant tree and shrub species was sampled, while the total of the individuals was considered for the low frequency host species. The damages caused by the organisms were: chlorosis, gills or cecidia, defoliation, damage to phloem and bark. Samples were obtained by direct collection in vials with 70 % alcohol. Most of the specimens collected were insects and sap sucking mites; the secondary damage associated with them was the formation of fumagins. The tree species most susceptible to pests was Salix bonplandiana, with 10 species of phytophagous that represented 19 % of the total found on the trees in the park. Derived from this study, the Eulophidae wasp and gill-forming aphelinidae in S. bonplandiana, the Specularius impressithorax bruch and the seed borer in Erythrina coralloides are recorded for the first time.

Key words Galls; urban trees; defoliating insects; bark beetles; phytophagous insects; Salix bonplandiana Kunth

Los árboles urbanos y suburbanos son elementos esenciales en las zonas pobladas, ya que tienen la capacidad de transformar las ciudades al aportar beneficios ambientales, estéticos, culturales y económicos. En la Ciudad de México, el parque Tezozómoc es muy importante para los habitantes de la zona norte por tener integrado un lago central artificial rodeado de abundante vegetación. Sin embargo, su arbolado ha presentado daños por diferentes agentes causales, por lo que en este estudio se detectaron y determinaron los insectos y ácaros fitófagos. Para el diagnóstico se muestreó 10 % de la frecuencia total de las especies dominantes de árboles y arbustos, mientras que para las especies de hospederas de poca frecuencia se consideró el total de los individuos. Los daños causados por los organismos fueron: clorosis, agallas o cecidias, defoliación, daños en floema y corteza. La obtención se realizó mediante colecta directa en frascos viales con alcohol al 70 %. La mayoría de los ejemplares colectados fueron insectos y ácaros chupadores de savia; el daño secundario asociado a ellos fue la formación de fumaginas. La especie arbórea más susceptible a plagas fue Salix bonplandiana, con 10 especies de fitófagos que representaron 19 % del total encontrado sobre los árboles del parque. Se registran por primera vez la avispa Eulophidae y a la formadora de agallas Aphelinidae en S. bonplandiana, el bruquido Specularius impressithorax y el barrenador de semilla en Erythrina coralloides.

Palabras clave Agallas; arbolado urbano; defoliadores; descortezadores; insectos fitófagos; Salix bonplandiana Kunth

Introduction

Plant species face different types of selective pressures of a biotic and abiotic nature during their growth and development. The first type highlights the damage caused by phytophagous and pathogens; among abiotic factors, deficiencies in the nutritional quality of the soil, water, microclimatic conditions, pH and light (Azcon, 1993), which leads to the mechanical or physiological deterioration of trees, such as deformations, decreased growth , weakening or even death, with the consequent ecological, economic and social impact (Semarnat, 2002).

Of the five major orders of insects derive the majority of those that feed on plants (Coleoptera, Lepidoptera, Himenoptera, Diptera and Hemiptera). These arthropods are considered the first and most important consumers of vegetables in terrestrial systems, and together with mites, outnumber herbivorous vertebrates (Daly et al., 1998).

Any phytophagous population, whether plague or not, is influenced by the abiotic (physical and chemical) and biological environment that surrounds it: climate, water, soil, plants, other pests, natural enemies and alterations that produce cultural practices, as well as pesticide applications. The alterations that occur in such components usually have an impact on the levels reached by pest populations (Cisneros, 2010).

Foliage is the predominant photosynthetic part of plants, so their absence from pests, for example, results in the loss of the photosynthetic area and a reduction in the production of carbohydrates (Resh and Cardé, 2003). In the case of urban green areas, this behavior is particularly important due to the vital functions that this vegetation exerts: regulation of the microclimate, balance and control of environmental problems, landscape architecture, habitat of different species of fauna, recreation and recreation (González and García, 2007). Therefore, it is important to know the entomofauna that affects urban trees, due to the benefits it brings. In this context, the objective of this study was to identify insects and phytophagous mites, as well as their effect with the physical state of the trees of the Tezozomoc Cultural and Recreational Park (PCyRT), Azcapotzalco, Mexico City.

Materials and Methods

Location and description of the study area

The Tezozómoc Cultural and Recreational Park (PCyRT) was designed in 1978 by the architect Mario Schjetman de Garduño, and opened on March 21, 1982 as a cultural-recreational space, in a densely populated area in the northwest of Mexico City, where there are few green areas. The purpose of this project was to recreate the topography-orography of the Valley of Mexico and its five lakes from the end of the 15th century, to offer through an cultural tour an historical and ecological vision in an easy and attractive way (Reséndiz et al., 2015).

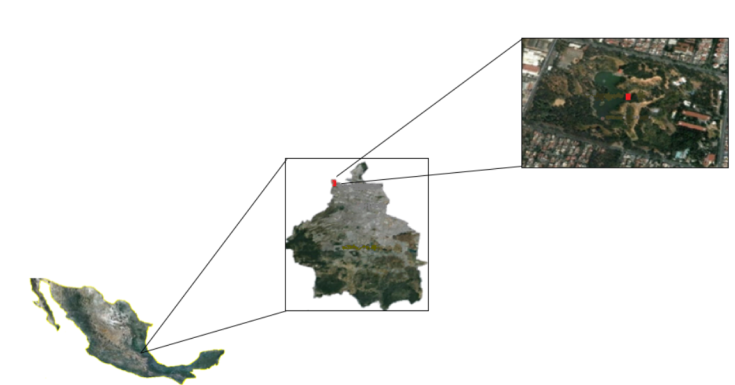

The PCyRT is located northwest of the Azcapotzalco City Hall in Mexico City; its coordinates are 19°29’05” N and 99°12’38” West, at 2 250 meters above sea level (Figure 1). It covers an area of 270 000 m2 (González and Moctezuma, 1999-2000). It borders to the north with the Tlalnepantla municipality, to the west with the municipality Naucalpan, to the south with the Cuauhtémoc and Miguel Hidalgo mayoralties and to the East with that of Gustavo A. Madero.

According to the Azcapotzalco weather station, the climate corresponds to type C (w0), subhumid temperate with rains in summer, of medium humidity, according to the Köeppen classification modified by García (Cuaderno Estadístico Delegacional, 2000).

At present, the soils in the Tezozómoc Park are sanitary landfills composed mainly of rubble and various garbage materials, so given its anthropic influence this type of soil is known as Androsol.

The flora of the park is represented by the following species, some of which are present in other major urban parks such as San Juan de Aragón (González et al., 2014): eucalyptus (Eucalytus globulus Labill.; E. camaldulensis Dehnh), ash (Fraxinus uhdei (Wenz.) Lingelsh), white poplar (Populus alba L.), jacaranda (Jacaranda mimosifolia D. Don), peach (Prunus persica (L.) Stokes), Mexican hawthorne (Crataegus mexicana DC.), avocado (Persea americana Mill.), Chinese orange blossom (Pittosporum tobira (Thunb.) A. T. Aiton), laurel rose (Nerium oleander L.), scarlet firethorn (Pyracantha coccinea M. Roem.), orchid tree (Bauhinia variegata L.), Montezumae cypress (Taxodium mucronatum Ten.), ahuejote (Salix bonplandiana Kunth), loquat (Eriobotrya japonica (Thunb.) Lindl.), ficus (Ficus microcarpa L. F.; Ficus benjamina L.), casuarina (Casuarina equisetifolia L.), weeping willow (Salix babylonica L.), flame coral tree (Erythrina coralloides DC.), privet (Ligustrum lucidum A. T. Aiton; Ligustrum japonicum Thunb.), cedar (Cupressus sempervirens L.), cypress (Cupressus lusitanica Mill.), Peruvian peppertree (Schinus molle L.), radiata pine (Pinus radiata D. Don), flagship pine (Pinus radiata var. binata (Engelm.) Lemmon), Mexican pinyon (Pinus cembroides Zucc.), palm (Phoenix canariensis Hort ex Chabaud.), yuca (Yucca guatemalensis Baker.) and rubber tree (Ficus elastica Roxb. ex Hornem.), trembling poplar (Populus tremuloides Michx.), swamp wattle (Acacia retinodes Schltdl.), wild black cherry (Prunus serotine Ehrn. ssp. Capuli (Cav.) Mc Vaugh), oak (Quercus acutifolia Née) and yucca (Yucca elephantipes Regel ex Trel.).

Field work

In order to know the general state of the study area, a preliminary tour was initially made in the Tezozomoc park with the help of a map provided by its administration. The different areas of the park were recognized, as well as their distribution and the type of aggregation of the trees; subsequently, a census of August 2009-2010 was carried out. From the botanical samples collected, the trees were identified based on the work of Rodríguez and Cohen (2003) and Martínez and Tenorio (2008). Pine samples were taken to the Forest Entomology and Phytopathology Laboratory of Cenid Comef from the Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Agrícolas y Pecuarias (INIFAP).

Entomological material collection. The health status assessment considered 10 % of the most frequent species from the census carried out; of the less frequent species, all the individuals were included. Samples of leaves, branches, fruits and bark were taken; the technique of beating and direct collection was applied, as well as a tray with 70 % alcohol. The plant material was placed in plastic bags to prevent desiccation and insects collected in the field were stored in vial tubes with 70 % alcohol, immature forms, such as nymphs, larvae or pupae that were found at the time sampling was collected and kept in breeding chambers (boxes) with part of plant material in the case of nymphs and larvae, in order to obtain the adult phases; this procedure was carried out in the Pest Control Laboratory of the Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala (Iztacala Graduate Studies School) where it was finally identified.

Laboratory work

Determination of pines. Cones, bark and needle samples were taken. Cross-sections were made of the latter and placed on slides to observe the arrangement and number of the channels in the optical microscope (Carl Zeiss Axiostar Plus) and contrast them with the keys of Farjon et al. (1997) and Martínez (1948).

Entomological determination. The collected insects were observed under a stereoscopic Carl Zeiss Stemi 2000-C microscope and photographs were taken with a Canon Power Shot A640® camera. The taxonomic determination was made at the family, genus and species level through the support of the taxonomic keys of Ferris (1938), Peterson (1973), Stehr (1987), Blackman and Easton (1994, 2006), Halbert (2001) , Triplehorn et al. (2005), Bautista (2006) and Unruh and Gullan (2008).

The assemblies were made according to the characteristics and size of the organisms: the dry assembly was carried out using entomological pins (bed bugs and beetles), as well as by specialized techniques in slides with Canadian balm (aphids and scales). In the case of mites, direct assembly with Hoyer's liquid was used (Remaudière, 1992; Solís, 1993; Triplehorn et al., 2005).

Statistical analysis

To process the data obtained from the mite and insect samples, the relative frequency (F) was used, which is considered as the number of times in which a species appears recorded at least once and is expressed as a percentage (Dix, 1961), whose formula is:

Where:

mi= Number of sampes where one species appeared in the total number of samples (M).

To determine whether there is independence between the sanitary condition (insects and mites) and the physical state of the crown and the tree trunk, a χ2 test was used with the following formula:

Where:

Σi=1…r (sum of the number of populations or rows of the contingency table)

Σj=1…c (sum of categories or columns of the contingency table)

Oij = Observed frequency per cell

Eij = Expected frequency per cell

The criteria used to determine the percentage of damage are based on the following categories: minimum (0 to 25 %), significant (26 to 50 %), Severe (51 to 75 %) and very severe (76 to 100 %) (Benavides, 1996).

The hypotheses raised were the following:

Null hypothesis (Ho): the presence of insects or mites are independent of the physical condition of the trees.

Alternative hypothesis (Ha): the presence of insects or mites if it is dependent on the physical condition of the trees.

According to Durán et al. (2005), the decision rule was applied to reject the null hypothesis (Ho): χ20> χ2α, (r-1) (c-1).

Results and Discussion

Tree composition

According to the census, in the Tezozómoc Park there are 3 758 trees made up of 30 species that are grouped into 16 botanical families, of which 15 are native and 15 exotic. Regarding the permanence of the foliage, it was observed that 67 % (20) are evergreen and 33 % (10) are deciduous (Table 1).

Table 1 Listado de especies arbóreas en las que se ubicó a los fitopatógenos del parque Tezozomoc.

| Species | Family | Number of trees |

|---|---|---|

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | Myrtaceae | 1 142 |

| Populus tremuloides Michx. | Salicaceae | 680 |

| Schinus molle L. | Anarcardiaceae | 380 |

| Pinus radiata var. binata (Engelm.) Lemmon | Pinaceae | 370 |

| Cupressus lusitanica Mill. | Cupresaceae | 214 |

| Erythrina coralloides DC. | Fabaceae | 175 |

| Fraxinus uhdei (Wenz.) Lingelsh. | Oleaceae | 150 |

| Total | 3 111 |

Determination of insects and mites

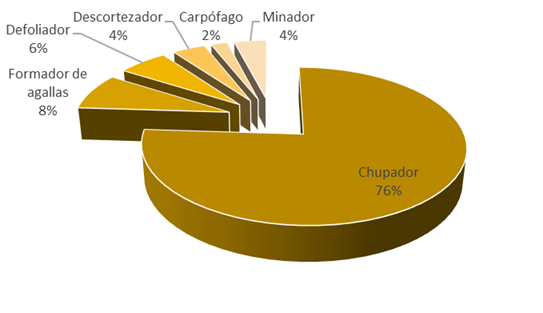

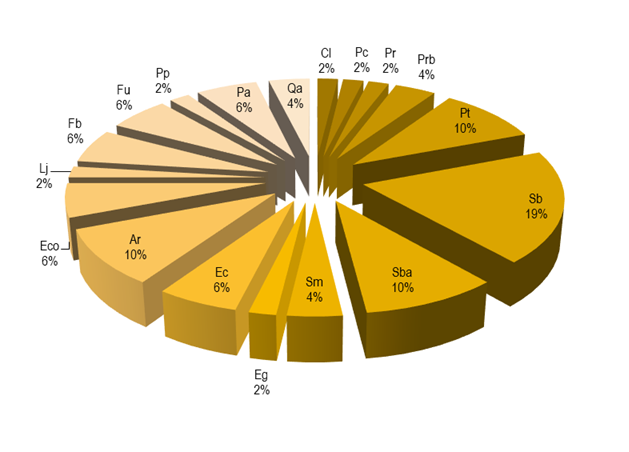

The phytophagous entomofauna and acarofauna grouped into 45 species included in 34 genera, 18 families and 6 orders (Table 2). The main eating habits of organisms are suckers (76 %) (Figure 2), which may be a consequence of the most abundant families being Aphididae (20 %), followed by Tetranychidae (13 %) (Figure 3); while, in the hosts the one that presented more phytophagous species was Salix bonplandiana (11), followed by Populus tremuloides (6) and Acacia retinodes (5) (Figure 4).

Table 2 Phytofagous mites and insects collected in each tree species.

| Entomofauna | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tree species | Order | Family | Species | Common name | Damaged structure | Damage kind | Frequency (%) |

| Cupressus lusitanica Mill. | Coleoptera | Curculionidae | Phloeosinus baumanni Hopkins | Bark beetle | Trunk | Debarking | 10.15 |

| Hemiptera | Aphididae | Cinara Curtis | Fleam | Sucker | |||

| Pinus cembroides Zucc. | Hemiptera | Diaspididae | Chionaspis Signoret | Pine sclae | Foliage | Sucker | 29.63 |

| Pinus radiata D.Don | Hemiptera | Diaspididae | Pine sclae | Foliage | Sucker | 100 | |

| Hemiptera | Aphididae | Eulachnus rileyi Williams | Fleam | Sucker | |||

| Pinus radiata var. binata (Engelm.) Lemmon | Hemiptera | Diaspididae | Pine sclae | Foliage | Sucker | 41.34 | |

| Coleoptera | Curculionidae | Bark beetle | Trunk | Debarking | 6.61 | ||

| Populus tremuloides Michx. | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | Empoasca Walsh | Little cicada | Foliage | Sucker | 45.00 |

| Alebra Fieber | Little cicada | Foliage | Sucker | 45.45 | |||

| Tingidae | Corythucha salicata Gibson | Lace bug | Foliage | Sucker | 20 | ||

| Aphididae | Pemphigus populitransversus Riley | Fleam | Petiole | Gill-forming | 1.51 | ||

| Chaitophorus Koch | Fleam | Foliage | Sucker | 3.8 | |||

| Diptera | Minelayer | Foliage | Minelayer (chewer) | 13.64 | |||

| Salix bonplandiana Kunth | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | Alebra Fieber | Little cicada | Foliage | Sucker | 95 |

| Tingidae | Corythucha salicata Gibson | Lace bug | Foliage | Sucker | 20 | ||

| Aphididae | Macrosiphum californicus Baker | Fleam | Foliage (new buds) | Sucker | 25 | ||

| Cavariella pustula Essig | Fleam | Foliage | Sucker | 25 | |||

| Pterocomma smithiae Monell | Red fleam | Branches | Sucker | 35 | |||

| Hymenoptera | Eulophidae o Aphelinidae | Wasp | Foliage | Gill-forming | 65 | ||

| Lepidoptera | Gracillariidae | Phyllocnistis Zeller | Minelayer | Foliage | Minelayer (chewer) | 75 | |

| Geometridae | Caterpillar | Foliage | Defoliador | 5 | |||

| Hemiptera | Largidae | Stenomacra marginella Herrich-schaeffer | Red bug | Foliage | Sucker | 15 | |

| Prostigmata | Eriophydae | Aculops tetanothrix Nalepa | Eriophid | Foliage | Gill-forming | 95 | |

| Tetranychidae | Tetraniquid | Foliage | Sucker | 40 | |||

| Salix babylonica L. | Prostigmata | Tetranychidae | Eotetranychus lewisi McGregor | Tetraniquid | Foliage | Sucker | 26.31 |

| Hemiptera | Aphididae | Pterocomma smithiae Monell | Fleam | Branches | Sucker | 15.8 | |

| Chaitophorus pusilus Hottes and Frison | Fleam | Foliage | Sucker | 10.53 | |||

| Largidae | Stenomacra marginella Herrich-schaeffer | Red bug | Foliage | Sucker | 10.53 | ||

| Schinus molle L. | Lepidoptera | Arctiidae | Lophocampa Harris | Tussok moth | Foliage | Defoliation | 2.41 |

| Hemiptera | Psyllidae | Calophya rubra Blanchard | Psyllid | Foliage | Gill-forming | 100 | |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | Hemiptera | Psyllidae | Ctenarytaina eucalypti Maskell | Psyllid | Foliage (new buds) | Sucker | 100 |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | Hemiptera | Largidae | Stenomacra marginella Herrich-schaeffer | Red bug | Foliage | Sucker | 4.2 |

| Psyllidae | Blastopsylla occidentalis Taylor | Psyllid | Foliage | Sucker | 34.45 | ||

| Glycaspis brimblecombei Moore | Red gum lerp psyllid | Foliage | Sucker | 100 | |||

| Acacia retinodes Schltdl. | Prostigmata | Tetranychidae | Mite | Foliage | Sucker | 83.67 | |

| Hemiptera | Aleyrodidae | White little fly | Foliage | Sucker | 14.29 | ||

| Monophlebidae | Icerya Douglas | Scale | Branches | Sucker | 2.04 | ||

| Aphididae | Macrosiphum Linnaeus | Fleam | Fruit (pods) | Sucker | 2.04 | ||

| Diaspididae | Aspidiotus Bouche | Scale | Foliage | Sucker | 83.67 | ||

| Erythrina coralloides DC. | Coleoptera | Bruchidae | Specularius impressithorax Pic | Bean weevil | Fruit (pods) | Carpofagous (borer) | 5 |

| Prostigmata | Tetranychidae | Mite | Foliage | Sucker | 20 | ||

| Hemíptera | Coccidae | Toumeyella erythrinae Kondo and Williams | Scale | Branches (females), Foliage (males). | Sucker | 100 | |

| Ligustrum japonicum Thunb. | Hemiptera | Largidae | Stenomacra marginella Herrich-schaeffer | Red bug | Foliage | Sucker | 100 |

| Ficus benjamina L. | Hemiptera | Cicadellidae | Empoasca Walsh | Little cicada | Foliage | Sucker | 23.3 |

| Alebra Fieber | Little cicada | Foliage | Sucker | 23.3 | |||

| Aphididae | Greenidea ficicola Takahashi | Fleam | Foliage | Sucker | 3.3 | ||

| Fraxinus uhdei (Wenz.) Lingelsh. | Hemiptera | Miridae | Tropidosteptes chapingoensis Carvalho | Ash tree bug | Foliage | Sucker | 100 |

| Prostigmata | Tetranychidae | Olygonichus punicae Hirst | Mite | Foliage | Sucker | 34.28 | |

| Eriophydae | Aceria fraxiniflora Felt | Eriophid | Flower | Gill-forming | 7.14 | ||

| Prunus serotina subsp. Capulli (Cav. ex Sreng.) McVaugh | Lepidoptera | Arctiidae | Lophocampa Harris | Tussok moth | Foliage | Defoliation | |

| Persea americana Mill. | Hemiptera | Aleyrodidae | White little fly | Foliage | Sucker | ||

| Aethalionidae | Aethalion subquadratum Saussure | Avocado green fly | Branches | Sucker | |||

| Hoplophorion monograma Germar | Avocado periquitos | Branches | Sucker | ||||

| Prostigmata | Tetranychidae | Olygonychus persea Tuttle, Baker and Abbatiello | Mite | Foliage | Sucker | ||

| Quercus acutifolia Née | Prostigmata | Tetranychidae | Mite | Foliage | Sucker | ||

| Hemiptera | Aleyrodidae | White little fly | Foliage | Sucker | |||

Sb = Salix bonplandiana; Sba = Salix babylonia; Sm = Schinus molle; Eg = Eucalyptus globulus; Ec = Eucalyptus camaldulensis; Ar = Acacia retinodes; Eco = Erythrina coralloides; Lj = Ligustrum japonicum; Fb = Ficus benjamina; Fu = Fraxinus uhdei; Pp = Pinus patula; Pa = Persea Americana; Qa = Quercus acutifolia; Cl = Cupressus lusitanica; Pc = Pinus cembroides; Pr = Pinus radiate; Prb = Pinus radiata var. binate; Pt = Populus tremuloides.

Figure 4 Percentage of hosts affected by insects and mites.

The most frequent symptoms in the hosts were chlorosis or chlorotic points in the foliage, since the pathogens feed on the vascular tissue, mainly of the phloem, which causes the cells to collapse and block the passage of nutrients, in severe infestations cause premature fall of the foliage, in addition to the fact that most of these species produce honeydew (Cibrián et al., 1995), (with the exception of mites) on which they develop fumagins, which are non-parasitic fungi, but live entirely of the honeydew produced by these insects, forming a dark and dense layer that reduces the amount of light that reaches the surface of the plant (Agrios, 2008). This fumagina was most evident in Erythrina coralloides caused by Toumeyella erythrinae Kondo and Williams in all trees (100 %).

Despite the observed frequency of Aspidiotus sp. (83.67 %) in Acacia retinodes, the percentage of damage could not be determined, because this host showed other problems such as a micromycete and abiotic factors, so it could not be defined which factor is affecting its health condition. However, the damage caused by Icerya sp. was minimal (0-25 %), because it sucks the sap in the branches and its frequency was minimal (2.04 %) for this host.

Although Stenomacra marginella, Alebra sp. and Empoasca sp. were frequent, had no significant effects (0-25 %) on their hosts (Ligustrum japonicum (100 %), Ficus benjamina (23 %) and Populus tremuloides (45 %); the above can be explained as they are polyphagous, that is, they feed on different plant species: The opposite occurred in Salix bonplandiana in which the damage was severe (51-75 %) since it presented chlorotic points on the leaf caused by a set of Tetraniquid species: S. marginella (95 %), Alebra sp. (95 %), Empoasca sp. (95 %) and Corythucha salicata (20 %); the latter was also observed in Populus tremuloides (20 %), with minimal damage (0-25 %).

On the other hand, the incidence of diaspidids (possibly of the Chinaseis genus) in Pinus radiata (100 %), P. cembroides (29.6 %), P. radiata var. binata (41.3 %) was minimal (0-25 %), which may be related to the fact that low density was recorded in all these species. The presence of Tropidosteptes chapingoensis Carvalho (100 %) was significant (26-50 %) in adult trees, and severe damage (51 to 75 %) was observed in young trees with a leaf yellowing, and chlorotic stippling, - characteristic symptom of this species- and foliage shed by 50 %. However, these expressions may be associated with different biotic factors such as other phytophagous insects and even abiotic factors such as air or soil pollutants.

The damage caused by aphids was very low (0-25 %) in the hosts Cupressus lusitanica (1 %), Pinus radiata (1 %), Acacia retinodes (2.04 %), Populus tremuloides (3.8 %), Ficus benjamina (3.3 %). In Salix bonplandiana (25 % and 35 %) it was significant (26-50 %) because it presented three different species of the Aphididae family.

The effects associated with the Tetranychidae family in their hosts (Erythrina coralloides (20 %), Fraxinus uhdei (34.28 %) and Salix babylonica (26.3 %) were minimal (0-25 %), as were the damages caused by Blastopsylla occidentalis Taylor (34.45 %) found in Eucalyptus camaldulensis, since in both cases not many organisms were found per host.

About the mites and insects forming gills or cecidia, Aculops tetanothrix Nalepa, 1889 is consigned, which causes the leaves to form a hard red structure that surrounds the mites; gills cause the leaves to bend and be shorter than those not infested, which favors their premature fall (Cibrián et al., 1995). This behavior is consistent with what was observed in the field in the Salix bonplandiana host in which the frequency was 100 %; in the same way, gills that were not red were recognized. The same symptoms produced by Aculops tetanothrix were identified in Schinus molle (100 %), but were caused by the psyllid Calophya rubra Blanchard, 1852 (100 %), with damage of 51 to 75 %, but without a severe infestation.

Organisms belonging to the Eulophidae or Aphelinidae family (65%) were found in some gills, since according to Triplehorn et al. (2005), there is no great anatomical difference between these families, so it was difficult to define the family to which this wasp belongs; both have been reported as parasitoids, and there are no records on wasps of them mthat form gills in Salix bonplandiana. However, there are data on wasps belonging to the Eulophidae family, which are gill-forming in Ophelimus eucalypti Gahan, 1922 (species native to Australia) and in Chile in Eucalyptus spp. (Gómez et al., 2006). The damage caused by these two phytophages in Salix bonplandiana was very severe (76-100 %). Another species belonging to this family is Quadrastichus erythrinae Kim, 2004, recorded in different species of Eritrina in Taiwan (Yang et al., 2004).

Among the mites and insects that make gills, the aphid is characterized by forming them in the petiole; therefore, the passage of water and nutrients to the leaves is partially interrupted, which leads to yellowing and premature fall of the foliage. In Populus tremuloides the damage by this organism was minimal (0-25 %) since its frequency was low (1.51 %). But, because it is a deciduous species, it causes the early loss of foliage and the presence of gills in the leaves that have fallen.

The erryphid Acerya fraxinoflora (7.14 %) is a newly reported mite for Fraxinus uhdei (Otero et al., 1999), which has caused significant damage (26-50 %) as it affects flower buds and manifests itself with deformation of the inflorescence in the form of gills and abortion of flowers. García (1981) described that the formation of these gills or cecidia resulted from the continuous stimulation of the invading organism, which uses the gill as a means to develop.

A genus of lepidoptera was also identified among defoliator insects: Lophocampa sp. on Schinus molle (2.41 %) and on Prunus serotina subsp. capulli. This lepidopter caused minimal damage (0-25 %) in its hosts, probably because they are more specific, since they are primary parasites that attack vigorous trees, and not individuals in a state of physiological deficiency (Dajoz, 2001). This is not the main cause of defoliators having less frequency in the park, since they play an important role in food chains by transforming plant biomass into animal biomass and serving as food for numerous predators such as birds, which in the park are abundant (Martínez and Leyva, 2014).

Another type of common damage is that caused by mining insects, which are characterized by forming a mine, path, channels or streamers in the leaflet since it feeds mainly on the leaf mesophyll and causes it to yellow (Méndez et al., 2008).

Two miners were registered in the park, an undetermined diptera in Populus tremuloides (13.64 %) and a lepidoptera of the Gracillariidae family, possibly of the genus Phyllocnistis sp., in Salix bonplandiana (75 %). They were counted at the rate of three dipterans per leaflet, while the microlepidopteros only one per leaflet. The damage caused by these insects was 26 to 50 %. Collected dipterans were found dead inside the mine without traces of parasitoids, possibly due to the plant itself or to endophytic fungi (Cornell and Hawkins, 1995), which can be explained because the defense chemicals are concentrated in the cuticle and in the cuticle. epidermis of the leaves.

In relation to the trunk, bark insects were less frequent, since they are only present when the trees are weakened by other factors, which, in extreme cases, results in the death of trees (Wood, 1982). Two species belonging to the Curculionidae family were found, one (Dentrictonus adjuntus Blanford, 1897) on Pinus radiata var. binata (6.61 %) and Phloeosinus baumanni Hopkins, 1905 in Cupressus lusitanica (10.15 %); in both species they caused severe damage (51 to 75 %). These barkers are characterized by feeding on the tissues of the vascular cambium and the inner bark of the trees.

Cibrián et al. (1995) indicates that Phloeosinus baumanni is not a primary pest for urban trees, but it becomes infested when it is weakened or in decline; they also mentioned that in Valle de México it is common to observe it on old trees of Cupressus benthamii and C lindleyi; however, these author do not specify location of plagued areas in the region nor percentage of damage.

NOM-019-SEMARNAT-2006 establishes that in Mexico there are bark insects of the Dendroctonus, Ips, Phloesinus and Scolytus genera, among others. Several of its species have an economic impact, to the extent that they are recognized as the most harmful forest pests in the country (Semarnat, 2012). Of the genera mentioned in the norm, Phloesinus spp. was detected in this study. on the trees of Cupressus lusitanica.

Another type of damage that was infrequent and less representative in terms of the number of species corresponds to carpal ghosts of Specularius impressithorax (Pic), which affected only 5 % of the individuals of Erythrina coralloides. This bruquido feeds on the seeds of the color; its distribution in Mexico and the severity of its damage are unknown, since it is a poorly reported species (Romero et al., 2009).

Table 3 Results of χ2 and significance observed in the comparison of the health and physical state of the crown.

| Species | χ2 | Observed significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cupressus lusitánica Mill. | 21.387 | 8.747E-05 |

| Pinus cembroides Zucc. | 12.5 | 0.019 |

| Pinus radiata D.Don | 22 | 2.727E-06 |

| Pinus radiata var. binata (Engelm.) Lemmon | 93.472 | 5.043E-21 |

| Pinus patula Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. | 30 | 4.320E-08 |

| Populus tremuloides Michx. | 142.216 | 1.258E-30 |

| Salix babylonica L. | 10.363 | 0.0012 |

| Salix bonplandiana Kunth | 31.544 | 1.414E-07 |

| Acacia retinodes Schltdl. | 0.196 | 0.658 |

| Erythrina coralloides DC. | 3.243 | 0.072 |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | 15.827 | 0.0004 |

| Eucalyptus globulus Labill. | 10 | 0.0015 |

| Schinus molle L. | 6.666 | 0.0098 |

| Fraxinus uhdei (Wenz.) Lingelsh | 92 | 1.053E-20 |

| Prunus pérsica (L.) Stokes | 12 | 0.00053 |

| Ligustrum japonicum Thunb. | 8 | 0.0046 |

| Ficus benjamina L. | 60 | 9.485E-15 |

| Yucca elephantipes Regel ex Trel. | 56 | 7.247E-14 |

Table 4 Results of χ2 and significance observed in the comparison of the health and physical state of the trunk.

| Species | χ² | Observed significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cupressus lusitánica Mill. | 74.746 | 5.700E-17 |

| Pinus radiata var. binata (Engelm.) Lemmon | 19.599 | 2.050E-04 |

| Schinus molle L. | 58.032 | 2.578E-14 |

| Populus tremuloides Michx. | 240.711 | 6.679E-52 |

| Salix babylonica L. | 22.166 | 1.537E-05 |

| Salix bonplandiana Kunth | 3.243 | 0.071 |

| Acacia retinodes Schtdl. | 67.618 | 1.381E-14 |

| Erythrina coralloides DC. | 40 | 2.539E-10 |

| Eucalyptus camaldulensis Dehnh. | 238 | 2.084E-52 |

| Ficus benjamina L. | 3.158 | 0.075 |

The value of α was 0.05; when the observed significance was greater, the null hypothesis (Ho) was accepted; in Acacia retinodes and Erythrina coralloides this hypothesis was accepted (Table 2), which means that the physical state of the crown is independent of the presence of insects and mites. In the case of the first species, other factors were observed that could influence their condition, such as exposed roots, because 16 % of the trees did not show foliage; while in E. coralloides the damage caused by the phytophagous did not influence the physical state of the leaves.

On the other hand, the physical condition of the crown of Cupressus lusitanica, Pinus cembroides, P. radiata var. binata, P. radiata, P. patula, Populus tremuloides, Salix babylonica, S. bonplandiana, Eucalyptus camaldulensis, E. globulus, Fraxinus uhdei, Prunus persica, Ligustrum japonicum, Schinus molle, Ficus benjamina and Yucca elephantipes was affected by the presence of those entomological agents.

In P. radiata var. binata, C. lusitanica, E. camaldulensis, S. molle, P. tremuloides, S. babylonica, S. bonplandiana, A. retinodes and E. coralloides, dependence was confirmed between the presence of bark beetles and the physical condition of the trunk.

The debarkers of P. radiata var. binata and C. lusitanica caused mechanical damage to the trunk; in S. molle, P. tremuloides, S. babylonica, S. bonplandiana, A. retinodes, E. coralloides and E. camaldulensis no debarking was found.

Conclusions

The trees and shrubs determined in this park comprised 30 species, of which half were native and the other half exotic. The mostly used for reforestation were four: Eucalyptus camaldulensis, Populus tremuloides, Schinus molle and Pinus radiata var. binata, which suggests little tree diversity.

When assessing the relationship of the sanitary condition and the physical state of the crown and trunk, it was concluded that in most of the hosts the damages were due to the action of insects and phytophagous mites, while Salix bonplandiana was the most susceptible tree species to pests with 10 species of insects and mites, which represented 19 % of the total phytophagous entomofauna found in the park. The Eulophidae or Aphelinidae gill-forming wasp in S. bonplandiana and the existence in the park of Specularius impressithorax as seed borer of Erythrina coralloides are considereded new reports.

Referencias

Agrios, G. N. 2008. Fitopatología. Editorial Limusa. México, D.F., México. 838 p. [ Links ]

Azcon B., J. y M. Talón. 1993. Fundamentos de fisiología vegetal. Mc Graw Hill. México, D. F., México. 489 p. [ Links ]

Bautista M., N. 2006. Insectos plaga, Una guía ilustrada para su identificación. Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillo, Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. 113 p. [ Links ]

Benavides M., H. y C. Segura. 1996. Situación del arbolado de la Ciudad de México: Delegaciones Iztacalco e Iztapalapa, Distrito Federal. Revista Ciencia Forestal en México 21(77):121-164. [ Links ]

Blackman, R. L. and V. F. Eastop. 1994. Aphids on the world’s trees. An identification and information guide. CAB International. Cambridge, UK. 986 p. [ Links ]

Blackman, R. L. and V. F. Eastop. 2006. Aphids on the world’s herbaceous plants and shrubs. John Wiley & Sons. Chichester, UK. 1460 p. [ Links ]

Cibrián T., D., J. Méndez M., R. Campos B., Y. Harry O. y J. Flores L. 1995. Insectos forestales en México. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. 587 p. [ Links ]

Cisneros F., H. 2010. Consideraciones ecológicas sobre las plagas y los campos de cultivo. AgriFoodGateway Horticulture International. Department of Horticultural Science. College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. North Caroline State University. Raleigh, NC USA https://hortintl.cals.ncsu.edu/sites/default/files/articles/Control_de_Plagas_Agricolas_MIP_Ene_2010.pdf (1 de febrero de 2018). [ Links ]

Cornell, V. H and B. A. Hawkins. 1995. Survival patterns and mortality sources of herbivorous insects: Some demographic trends. American Naturalist 145(4): 563-593. Doi: 10.1086/285756. [ Links ]

Cuaderno Estadístico Delegacional. 2000. Departamento de Parques y Jardines. Azcapotzalco, México, D. F., México. 41 p. [ Links ]

Dajoz, R. 2001. Entomología forestal: los insectos y el bosque. Ediciones Mundi Prensa. Madrid, España. 550 p. [ Links ]

Daly, H. V., J. T. Doyen and -A. H. Purcell. 1998. Introduction to insect biology and diversity. Oxford University Press. New York, NY USA. 680 p. [ Links ]

Durán D., A., C. Cisneros y A. Vargas V. 2005. Bioestadística. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Facultad de Estudios Superiores Iztacala. Tlalnepantla, Edo. de Méx., México. 89 p. [ Links ]

Dix, R. L. 1961. An application of the Point-Centered Quarter Method to the Sampling of Grassland Vegetation. Journal of Range Management 14:63-69. Doi: 10.2307/3894717. [ Links ]

Farjon, A., B. Thomas y J. A. Pérez de la Rosa. 1997. Guía de campo de los pinos de México y América Central. The Kew Royal Botanic Gardens. Richmomnd, England. 151 p. [ Links ]

Ferris, G. F. 1938. Atlas of the scale insects of North America. Introduction supplementary note. Stanford University. San Francisco, CA USA. 237 p. [ Links ]

García, M. C. 1981. Lista de insectos y ácaros perjudiciales a los cultivos en México. 2 SARH. México, D. F., México. 196 p. [ Links ]

Gómez, M., J. F., A. M. Hernández N., A. M. Garrido T., R. Askew y J. L. Nieves A. 2006. Los Chalcidonea (Hymenoptera) asociados con agallas de Cinípidos (Hymenoptera, Cynipidae) en la comunidad de Madrid. Graellsia 62:293-331. Doi: 10.3989/graellsia.2006.v62.iExtra.122. [ Links ]

González O., G y J. García V. 2007. Riesgo por caída de árboles en un Parque Metropolitano de Guadalajara, Jalisco, México. Instituto de Medio Ambiente y Comunidades Humanas, Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias. Universidad de Guadalajara. Guadalajara, Jal., México. pp. 93-98. [ Links ]

González, H., A., K. I. Toledo G., V. M. Jiménez E. y F. Moreno S. 2014. Distribución espacial del arbolado del Bosque San Juan de Aragón. Folleto Técnico Núm. 14. Cenid-Comef, INIFAP. México, D.F., México. 52 p. [ Links ]

González, M. y B. Moctezuma. P. 1999-2000. Ciudad de México. Delegación Azcapotzalco. Monografía. Edición Delegacional. México, D.F., México. pp.7-74. [ Links ]

Halbert, E. S., R. J. Gill and J. N. Nisson. 2001. Two Eucalytus psylids new to Florida (Homoptera: Psyllidae). Entomology Circular Num. 407. Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services. Division of Plant Industry. Gainesville, FL USA. 2 p. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2000. Azcapotzalco. Distrito Federal. Cuaderno Estadístico Delegacional. México, D.F., México. pp.3-14. [ Links ]

Martínez, M.1948. Los pinos mexicanos. Ediciones Botas. México D. F., México. 361 p. [ Links ]

Martínez G., L. y P. Tenorio L. 2008. Árboles y áreas verdes urbanas de la Ciudad de México y su Zona Metropolitana. Fundación Xochitla, A. C. Méxic, D. F., México. 549 p. [ Links ]

Martínez R., A. y A. Leyva G. 2014. La biomasa de los cultivos en el ecosistema. Sus beneficios agroecológicos. Cultivos Tropicales 35(1) 11-29. [ Links ]

Méndez, M. T. J., S. García, S., B. Don Juan, M., L. Ángel, A. 2008. Diagnostico fitosanitario en plantaciones forestales comerciales en las Choapas, Veracruz y Huimanguillo, Tabasco. Comisión Nacional Forestal, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. 112 p. [ Links ]

Otero C., G., D. H. Noriega, C. R. Sánchez M. R., M. C. Acosta R., M. T. Santillán G. y F. Miranda Z. 1999. Descripción morfológica de la escoba de bruja del mango en brotes vegetativos y florales. Colegio de Postgraduados. Instituto de Fitosanidad. Montecillo, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 5-7. [ Links ]

Peterson, A. 1973. Larvae of insects an introduction to Nearctic species. Part 1. Lepidoptera and a Plant Infesting Hymenoptera. Edwards Brothers. Columbus, OH USA. 315 p. [ Links ]

Remaudière, G. 1992. Une mèthode simplifiée de montage des aphides et autres petis insectes dans le baume de Canadá. Revue française d’entomologie (N. S.) 14(4):185-186. [ Links ]

Reséndiz M., J. F., L. Guzmán D., A. Muñoz V., C. Nieto de Pascual P. y L. P. Olvera C. 2015. Enfermedades foliares del arbolado en el Parque Cultural y Recreativo Tezozómoc, Azcapotzalco, Cd. de México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 6(30): 106-123. Doi: 10.29298/rmcf.v6i30.211. [ Links ]

Resh, V. H. and R. T. Cardé (Eds.). 2003. Encyclopedia of insects. Academic Press. New York, NY USA. 1266 p. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, S. L. y E. J. Cohen F. 2003. Guía de árboles y arbustos de la zona metropolitana de la Ciudad de México. Gobierno del Distrito Federal. Secretaría del Medio Ambiente. México, D. F., México. 383 p. [ Links ]

Romero, N. J., J. M. Kingsolver and H. C. Rodríguez. 2009. First report of the exotic bruchid Specularius impressithorax (Pic) on seeds of Erythrina coralloides DC. in México (Coleoptera: Bruchidae). Acta Zoológica Mexicana 25(1): 195-198. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2012. Informe de la situación del medio ambiente en México. Compendio de Estadística Ambiental. México, D. F., México. 361 p. http://biblioteca.semarnat.gob.mx/janium/Documentos/Ciga/Libros2013/CD001623.pdf (1 de marzo de 2018). [ Links ]

Solís A., J. F. 1993. Escamas (Homoptera: Coccoidea). Descripción morfología y técnica de montaje. Serie: Protección Vegetal Núm. 3. Departamento de Parasitología Agrícola. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 34-35. [ Links ]

Stehr, F. W. 1987. Order Lepidoptera. In: Stehr, F. W. (ed.). Immature Insects. Vol. I. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Co. Dubuque, IA USA. pp. 288-340. [ Links ]

Triplehorn, C. A., F. N. Johnson and D. J. Borror. 2005. Introduction to the Study of insects. Thompson-Brooks/Cole. Belmont, CA USA. 864 p. [ Links ]

Unruh, C. M. and P. J. Gullan. 2008. Identification guide to species in the scale insect tribe Iceryni (Coccoidea: Monophlebidae). Zootaxa 1803. Auckland, New Zealand. 106 p. [ Links ]

Wood, S. L. 1982. The bark and ambrosia beetles of North and Central America (Coleoptera: Scolytidae) a taxonomic monograph. Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs 6:1-1356. [ Links ]

Yang, M. M., G. S. Tung, J. La Salle and M. L. Wu. 2004. Outbreak of erythrina gall wasp (Hymenoptera: Eulophidae) on Erythrina spp. (Fabaceae) in Taiwan. Plant protection Bulletin 46: 391-396. [ Links ]

Received: July 11, 2018; Accepted: September 13, 2019

![Identificación del agente causal de la antracnosis en el cultivo de hule [Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A. Juss.) Müll. Arg.]](/img/pt/prev.gif)

texto em

texto em