Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.10 no.56 México nov./dic. 2019 Epub 30-Abr-2020

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i56.551

Scientific article

Identification of the causal agent of antracnosis in the cultivation of the rubber tree [Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A. Juss.) Müll. Arg.]

1Centro Nacional de Investigación Disciplinaria en Conservación y Mejoramiento de Ecosistemas Forestales, INIFAP. México.

2Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo. México.

3Campo Experimental El Palmar, CIR-Golfo Centro, INIFAP. México.

In 2016, a disease developed in clonal rubber tree gardens (clone IAN-710) in San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, Oaxaca, the symptoms were observed in new leaves, buds and stems characterized by small watery spots that become in circular to irregular necrotic lesions, dark cream to black with yellow edges. Symptomatic samples were taken and 17 colonies were isolated in PDA media, seven from the stem and 10 from the leaves. The pathogen was determined using traditional techniques, PCR-Sequencing with the pair of ITS5 and ITS4 primers that amplified a 550 bp fragment. The phylogenetic analysis was performed with Bayesian inference with 1 000 000 generations and a final standard deviation of 0.008. The isolates presented morphological characteristics of the Colletotrichum genus, while phylogenetic analyzes indicated that the isolates were grouped within the species of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides complex.

Key words Antracnose; phylogenetic; phytopathogen; fungus; rubber; PCR

El hule es un producto estratégico para el desarrollo rural y su cultivo es una alternativa económica importante para las regiones del trópico húmedo de México, porque propicia una actividad ocupacional diversa y numerosa durante todas sus fases de producción, desde el trabajo en viveros hasta el establecimiento y mantenimiento de plantaciones forestales. En jardines clonales de hule (clon IAN-710) en el municipio San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, Oaxaca, en 2016 se presentó una enfermedad en las hojas nuevas, brotes y tallos caracterizada por pequeñas manchas acuosas que se convierten en lesiones necróticas de forma circular a irregular, de color crema oscuro a negro, con bordes amarillos. Se tomaron muestras sintomáticas de las cuales se aislaron 17 colonias en medio de cultivo PDA, siete de tallo y 10 de hojas. La determinación del patógeno se realizó mediante técnicas tradicionales y con PCR-Secuenciación con el par de iniciadores ITS5 e ITS4 que amplificaron un fragmento de 550 pb. El análisis filogenético se efectuó con inferencia bayesiana con 1 000 000 de generaciones y una desviación estándar final de 0.008. Los aislamientos presentaron características morfológicas del género Colletotrichum, mientras que los análisis filogenéticos indicaron que los aislados se agruparon dentro de las especies del complejo Colletotrichum gloeosporioides.

Palabras clave Antracnosis; filogenia; fitopatógeno; hongo; hule; PCR

Introduction

Rubber or rubber tree [Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A. Juss.) Müll. Arg.] belongs to the Euphorbiaceae family and is native to the Amazon plains in Latin America (Compagnon, 1998; SIAPa, 2018). In Mexico, its cultivation dates back to 1882, when the English and Dutch companies established the first plantations in the Tezonapa municipalities, in the state of Veracruz and in Tuxtepec, Ojitlán and Santa María Chimalapa, in the state of Oaxaca (Picón et al., 1997).

Rubber cultivation represents a strategic product, as it is considered an alternative for the development of the humid tropic regions of Mexico; from the socioeconomic point of view, it occupies a large workforce during all its cultivation phases, from the establishment of nurseries, to the establishment and maintenance of the plantations. In 2018, the total production of rubber in Mexico was 75 922.65 t, from the states of Veracruz, Chiapas, Tabasco, Oaxaca and Puebla as those that contribute the greatest part (Rojo et al., 2005; Izquierdo et al., 2008; SIAPb, 2018).

The rubber tree is susceptible to the attack by fungi, which are responsible for considerable losses in terms of latex production each year, as they affect the root, the perforation tapping panel, the stem, the branches and leaves (Anacafé, 2004). Among the most economically important pathogens worldwide, Microcyclus ulei (Henn.) Arx, Colletotrichum gloesporioides (Penz.) Penz & Sacc., Drechslera heveae (Petch) M. B. Ellis and Corynespora cassicola C. T. Wei stand out (Jaimes and Rojas, 2011). C. gloeosporioides is the causal agent of a various types of damage and symptoms in different crops in Mexico, as it affects several plant organs at different phenological stages (Gutiérrez et al., 2001).

Oaxaca ranks fourth nationally with a production of 6 457.82 t and a planted area of 4 021.50 ha (SIAPa, 2018). In 2016, a disease incidence of 6 % was recorded in San José Chiltepec and 63 % in San Juan Bautista, Tuxtepec, Oaxaca(Gijón et al., 2017); small circular to irregular necrotic spots were observed with yellow leaf edges and young stems. The producers of the region associated it with the damage caused by Microcyclus ulei (Henn.) Arx, but, when making the observations under a stereoscope microscope, the signs agreed with the disease known as anthracnose. For this reason, the management measures they have implemented in the producing area have not been efficient for disease control. Given the socio-economic importance of the crop and being the municipality with the largest area planted in the state (863 ha), a correct diagnosis of the pathogen is substantial, so the objective of the present investigation was to identify the causative agent associated with anthracnose in the cultivation of rubber.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

Walks in the rubber clonal gardens were made in October, 2016 in San Juan Bautista municipality, Tuxtepec, Oaxaca State. Twenty foliar samples and 10 stems with anthracnose symptoms were collected, which were processed at the Cenid Comef Forest Health Laboratory.

Isolation and purification of fungi

Plant material (leaves and stems) with anthracnose symptoms were cut into squares of approximately 1 cm²; they were disinfested with 1 % sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes, then rinsed three times with sterile distilled water and excess moisture was removed on sterile filter paper. Finally, they were placed in a humid chamber and in Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) culture medium.

Seeds of both methods were incubated at 28 ± 1 °C for five days with a 12: 12h controlled photoperiod. After the period, fungus growth was observed and purification was performed in PDA to obtain monosporic cultures. Those strains were preserved in inclined tubes with PDA culture medium with mineral oil.

Morphological characterization

From monosporic cultures in PDA, mycelium coloration and fungus growth were scored. Temporary and permanent preparations of the isolates were made, as well as mounting of cuts of the structures obtained in a humid chamber for visualization in optical microscopy with phase contrast (AxiolabdrbKT, Zeiss) and scanning electron microscopy (EVO MA15, Zeiss) by using the cryofracture technique, in order to obtain a higher resolution image that would allow to notice a more detailed approach to the structures present in the preparations. To determine the genus, general keys were used (Humber, 1997; Barnett and Hunter, 1999).

Molecular characterization

For the molecular study, two isolated strains of stem (M51 and M95) and three of leaves (M39, M46 and M48) were selected. DNA extraction was carried out by the modified AP (Alkaline Phosphatase) method (Sambrook and Russell, 2001) with four-day monosporic cultures of PDA growth. The ITS region was amplified with primers ITS5 (5´GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3´) and ITS4 (5´-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3´) (White et al., 1990), found in the conserved regions of the 18S and 28S genes respectively.

The PCR amplifications were performed in a Biorad T100 thermocycler with the following program: an initial denaturation cycle of 3 min at 94 °C, followed by 34 cycles, each consisted of three steps: denaturation of 30 s at 94 °C, annealing of 30 s to 58 °C and an extension of 1 min at 72 °C, finally an extension of 1 min at 72 °C. The purification of the PCR products was made with the WizardTM SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System Kit (Promega Corporation, 1999). Sequencing was performed at Macrogen Inc. in Seoul, Korea.

The sequences obtained were cleaned, assembled in Mega X and a search of reference sequences of the related species of the Colletotrichum complex deposited in the GenBank database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) was downloaded.

All sequences were aligned with the muscle method (Edgar, 2004) included in Mega X software (Kumar et al., 2018). Phylogenetic reconstruction was performed by Bayesian inference using Markov Chains Monte Carlo (MCMC), implemented in the Mr Bayes v.3.2.1 program (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) with 1 000 000 generations. The 25 % of the trees produced were discarded with the ‘burn-in phase’ option and the subsequent probability was determined with the remaining trees. Colletotrichum boninense Moriwaki, Toy. Sato & Tsukib. accession number JQ005162 was used as an outgroup.

Results and Discussion

Symptom description

The samples collected from rubber plants of clone IAN-710 showed symptoms of anthracnose (Figure 1A): in the leaves, small, circular, irregular, cream-colored necrotic water spots were observed, which later turned dark with yellow edges (Figure 1B) ; in addition, split black lesions and descending petiole death were observed in the stems (Figure 1C).

Morphological description

Seventeen monosporic isolates were obtained, seven of stems and 10 of leaves, which presented morphological characteristics of the Colletotrichum genus. White to light gray mycelial growth was observed, with small black dots and with salmon conidial masses in PDA (Figure 2A), cylindrical conidia, with rounded, hyaline, unicellular and fusiform ends (Figure 2B and 2C) that are located in a reproductive structure called acervulus. The septate and branched conidiophores originate in the upper part of the pseudoparenchyma.

A) Colonial development in PDA medium; B) Conidia observed in compound microscope (40x); C) Conidia seen in scanning electron microscope (mag 358X).

Figure 2 Colletotrichum morphology, isolated from rubber tree leaves.

Li et al. (2012) described Colletotrichum gloeosporioides with cylindrical conidia, obtuse at the ends, hyaline, smooth. The colonies in PDA with white, gray, dark gray or olive-gray mycelia and sporulation of orange and brown or olive green on the reverse, which is similar to that observed in the isolates obtained. Anthracnose in rubber cultivation is caused by species of the Colletotrichum genus, in particular by C. gloesporoides (Jaimes and Rojas, 2011).

The disease caused by this pathogen, usually occurs in the production sites of some plant species in the tropics. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Penz. is the causative agent of a variety of damages and symptoms in different crops in Mexico, and affects several plant organs at different phenological stages (Gutiérrez et al., 2001). It shows in nurseries, clonal gardens and adult plants and limits production by causing the death of affected young tissues (Grupo Técnico Procaucho, 2012).

Molecular description

The amplification of the PCR products with the ITS4 and ITS5 primers of the rDNA of the 17 isolates yield a fragment of approximately 550 bp (Figure 3).

M = Molecular marker 1kb, lane 1 to 7 strains of fungi obtained from stems, 8 to 17 strains of fungi obtained from leaves; (+) = Positive control (Colletotrichum sp isolated from mango); (-) = Negative control (Water free of nucleases).

Figure 3 PCR product amplification of Colletotrichum sp. associated with anthracnose in leaves and rubber stems.

Silva and Ávila (2011) obtained fragments of approximately 580 bp for Colletotrichum species isolated from avocado (Persea americana Mill.). On the other hand, Dominguez-Guerrero et al. (2012) reported a fragment of approximately 600 bp for Colletotrichum gloeosporioides of African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) and Martínez et al. (2015), 580 bp for isolates of C. gloeosporioides in litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.).

Phylogenetic analysis

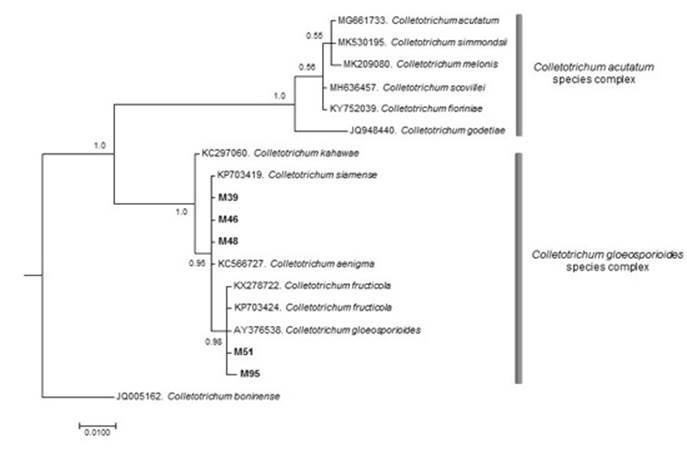

The resulting tree was obtained with 1 000 000 generations and a final standard deviation of 0.008780. The formation of two well-defined clades was observed, in the first clade, the species under study were included and in the second clade, six species corresponding to the C. acutatum J. H. Simmonds complex, the statistical support of both clades was equal to 1 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Phylogenetic consensus tree based on Bayesian inference that illustrates the relationship of Colletotrichum isolates associated with anthracnose in rubber cultivation within the complexes of Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. & Sacc. species.

The sequences of the M39, M46 and M48 isolates were grouped with sequences corresponding to C. siamense Prihast, L. Cai & K. D. Hyde and C. aenigma B. S. Weir & P. R. Johnst., as well as M51 and M95 with C. fructicola Pihasti, L. Cai & H. D. Hyde, these species have recently been described within the C. gloeosporioides species complex (Weir et al., 2012). The phylogenetic reconstruction showed that the isolates under study were different from the species included within the C. acutatum species complex (Damm et al., 2012a) and outside the C. boninense group (Damm et al., 2012b).

Based on the phylogenetic reconstruction of the ITS region of the rDNA, the M39, M46 and M48 isolates are found in the clade consisting of C. siamense and C. aenigma. Both species are phylogenetically related, although none of them have been declared as causing the effects of rubber in the country, so they represent ‘novel’ sequences for further studies.

With regard to the M51 and M95 isolates, they were identified as C. fructicola, together with the accession number AY376538 designated as C. gloeosporioides, this sequence has been reassigned in the C. fructicola subclade.

Conclusions

The anthracnose symptoms observed on the leaves and stems of rubber trees in San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, Oaxaca, were caused by Colletotrichum sp. and the phylogenetic analyses indicated that the studied isolates are part of the Colletotrichum gloeosporioides complex, which is made up by more than 22 species and two subspecies. This is the first report of the disease with scientific support for Colletotrichum in rubber plantations of México.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Programa de Fomento a la Agricultura de la Secretaria de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación (SAGARPA) (Program for the Promotion of Agriculture of the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food) (Sagarpa) for financing the development of this work that is part of the project “Actualización y transferencia de un paquete tecnológico para el cultivo del hule (Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) en el trópico húmedo mexicano” SURI: DF1600000621(“Update and transfer of a technological package for the cultivation of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) in the Mexican humid tropics” SURI: DF1600000621.

REFERENCES

Asociación Nacional del Café (Anacafé). 2004. Cultivo de hule. Programa de diversificación de ingresos de la empresa cafetalera. Guatemala, Guatemala. 23 p. [ Links ]

Barnett, H. L. and B. B. Hunter. 1999. Illustrated genera of imperfect fungi. The American Phytopathological Society Press. St. Paul, MN, USA. 218 p. [ Links ]

Compagnon, P. 1998. El caucho natural, biología-cultivo-producción. CIRAD-CMH. México, D. F., México. 695 p. [ Links ]

Damm, U., P. F. Cannon, J. H. Woudenberg and P. W. Crous. 2012a. The Colletotrichum acutatum species complex. Studies in Mycology 73(1): 37-113. Doi: 10.3114/sim0010. [ Links ]

Damm, U., P. F. Cannon, J. H. C. Woudenberg, P. R. Johnston, B. S. Weir, Y. P. Tan, R. G. Shivas and P. W. Crous. 2012b. The Colletotrichum boninense species complex. Studies in Mycology 73: 1-3. Doi: 10.3114/sim0002 [ Links ]

Domínguez-Guerrero, I. P., S. R. Mohali-Castillo, M. A. Marín-Montoya. y H. B. Pino-Mrnrdini. 2012. Caracterización y variabilidad genética de Colletotrichum gloeosporioides sensu lato en plantaciones de palma aceitera (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) en Venezuela. Tropical Plant Pathology 37(2): 108-122. Doi: 10.1590/S1982-56762012000200003. [ Links ]

Edgar R., C. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 32: 1792-1797. Doi:10.1093/nar/gkh340. [ Links ]

Gijón H., A., R., I. M. Pérez G., B. Torres H., E. Ortíz C., P. E. Sánchez G., X. R. Villagómez R. y J. F. Reséndiz M. 2017. Enfermedades del Cultivo de Hule [Hevea brasiliensis (Willd. ex A. Juss.) Müll. Arg.] . Folleto Técnico Núm. 23. Cenid-Comef, INIFAP. Coyoacán, Ciudad de México, México. 40 p. [ Links ]

Grupo Técnico Procaucho. 2012. Manejo integrado de plagas enfermedades en el cultivo del caucho (Hevea brasiliensis). Medidas para la temporada invernal. Instituto Colombiano Agropecuario (ICA). Bogotá, Colombia. 32 p. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez A., J. G., D. Nieto A., D. Téliz O., E. Zavaleta M., H. Vaqueda H., T. Martínez D. y F. Delgadillo S. 2001. Características de crecimiento, germinación, esporulación y patogenicidad de aislamientos de Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Penz. obtenidos de Frutos de Mango (Mangifera indica L.). Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 19 (1): 90-93. https://www.gob.mx/siap/articulos/hule-hevea-productor-de-latex?idiom=es (14 de mayo de 2019). [ Links ]

Humber, R. A. 1997. Fungi: Identification. In: Lacey, L. (ed.) Manual of techniques in insect pathology. Academic Press. San Diego, CA, USA. pp. 153-185. [ Links ]

Izquierdo B., H. 2008. Diagnóstico del manejo de cosecha y aplicación de estimulantes en plantaciones de hule Hevea basiliensis Müell Arg. en Tabasco. Tesis de maestría. Producción Agroalimentaria en el trópico. Colegio de Postgraduados. H. Cárdenas, Tab., México. 83 p. [ Links ]

Jaimes S., Y. Y. y J. Rojas M. 2011. Enfermedades foliares del caucho (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.) establecido en un campo clonal ubicado en el Magdalena Medio Santandereano (Colombia). Corpoica Ciencia y Tecnología Agropecuaria 12 (1): 65-76. Doi: 10.21930/rcta.vol12_num1_art:216. [ Links ]

Kumar, S., G. Stecher M., C. Knyaz L. and K. Tamura. 2018. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 35: 1547-1549. Doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [ Links ]

Li, Z., Y.-M. Liang and C. M. Tian. 2012. Characterization of the causal agent of poplar anthracnose occurring in the Beijing region. Mycotaxon 120: 277-286. Doi: 10.5248/120.277. [ Links ]

Martínez B., M., D. Téliz O., A. Mora A., G. Valdovinos P., D. Nieto Á., E. García P. and V. Sánchez L. 2015. Anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides Penz.) of litchi fruit (Litchi chinensis Soon.) in Oaxaca, México. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología. 33(2): 140-155. [ Links ]

Picón R., L., E. Ortiz C. y J. M Hernández C. 1997. Manual para el cultivo del hule Hevea brasiliensis Muell Arg. Folleto técnico núm. 18. Campo Experimental, El Palmar. INIFAP. Tezonapa, Ver., México. 128 p. [ Links ]

Promega Corporation. 1999. GenePrint@ Fluorescent STR Systems Technical Manual. Promega Corporation. Madison, WI, USA. https://www.ohio.edu/plantbio/staff/showalte/MCB%20730/STRmanual.pdf (9 de octubre de 2019). [ Links ]

Rojo M., G. E., J. Jasso M., J. Vargas H., D. Palma L. y A. Velázquez M. 2005. Análisis de la problemática de carácter técnico-económico del proceso productivo del hule en México. Ra Ximhai. 1(1): 81-110. [ Links ]

Ronquist, F. y J. Huelsenbeck P. 2003. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic reference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572-1574. Doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [ Links ]

Sambrook, J. and D. Russell. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA. 2100 p. [ Links ]

Servicio de Información Agropecuaria y Pesquera (SIAPa). 2018. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Agrícola. Cierre de producción Agrícola 2018. https://nube.siap.gob.mx/cierreagricola/ (14 de mayo de 2019). [ Links ]

Servicio de Información Agropecuaria y Pesquera (SIAPb). 2018. Hule hevea, productor de látex. https://www.gob.mx/siap/articulos/hule-hevea-productor-de-latex?idiom=es (14 de mayo de 2019). [ Links ]

Silva R., H. V. and G. D. Ávila Q. 2011. Phylogenetic and morphological identification of Colletotrichum boninense: a novel causal agent of anthracnose in avocado. Plant Pathology 60:899-908. Doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2011.02452.x. [ Links ]

Weir, B. S., P. R. Johnston and U. Damm. 2012. The Colletotrichum gloeosporioides species complex. Studies in Mycoloy. 73(1): 115-180. Doi:10.3114/sim0011. [ Links ]

White, T. J., T. Bruns, S. Lee and J. Taylor. 1990. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. Academic Press, Inc. New York, NY, USA. pp. 315-322. [ Links ]

Received: April 08, 2019; Accepted: October 04, 2019

texto en

texto en