Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.10 no.55 México Set./Out. 2019 Epub 14-Fev-2020

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i55.593

Scientific article

Accumulated carbon estimation in Gmelina arborea Roxb. from Tlatlaya, Estado de México with allometric equations

1Facultad de Ciencias Forestales. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. México.

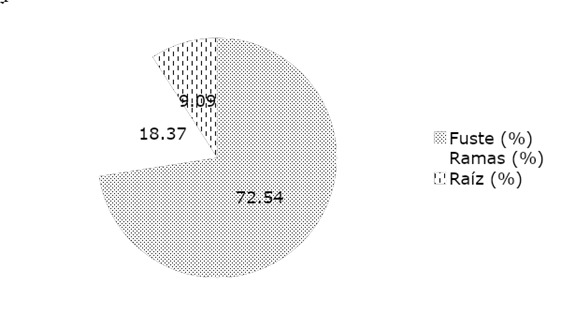

Based on the carbon storage capacity of forest species, the accumulated carbon in an eight ha plantation, of Gmelina arborea of different ages, established in 2014, was estimated by means of mensuration variables and allometric equations; This plantation is located in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico, at 694 masl, with a slope of 40 % and a density of 1 040 ha-1 trees. Work was carried out on eight permanent circular sampling plots of 400 m2 and a radius of 11.28 m, in which 207 trees were counted in total. An analysis of variance was performed and compared with the Tukey means test (p <0.05). The results indicate that the increase in DAP was 0.75 cm and the height of 0.54 m in the measurement period (six months); the biomass is distributed in the trunk (72.54 %), branches (18.37 %) and root (9.09 %) of the trees. The carbon accumulated in the tree components showed significant statistical differences in the ages evaluated. After three years the carbon accumulated in the trunk was 6.07 t ha-1, in the branches, 1.49 t ha-1, at the root of 0.76 t ha-1 and the total carbon accumulated, 8.31 t ha-1. It is concluded that the managed values of the predictive variables in the equation adjusted to estimate the carbon accumulated in the plantation of G. arborea vary by factors such as age, edaphoclimatic conditions, silvicultural practices and woodland density.

Key words Biomass; forest management; mathematical model; forest plantation; carbon sequestration; environmental services

Con base en la capacidad de almacenamiento de carbono de las especies forestales, se estimó el carbono acumulado en una plantación de 8 ha, de Gmelina arborea de diferentes edades, establecida en 2014, por medio de variables dasométricas y ecuaciones alométricas; dicha plantación se ubica en Tlatlaya, Estado de México, a 694 msnm, con una pendiente de 40 % y una densidad de 1 040 árboles ha-1. Se trabajó en ocho parcelas permanentes de muestreo, circulares de 400 m2y un radio de 11.28 m, en las cuales se contabilizaron 207 árboles. Se realizó un análisis de varianza y se comparó con la prueba de medias de Tukey (p<0.05). Los resultados indican que el incremento del DAP fue de 0.75 cm y la altura de 0.54 m en el periodo de medición (seis meses); la biomasa se distribuye en el fuste (72.54 %), ramas (18.37 %) y raíz (9.09 %) del arbolado. El carbono acumulado en los componentes del árbol mostró diferencias estadísticas significativas en las edades evaluadas. A los tres años el carbono acumulado en el fuste fue de 6.07 t ha-1, en las ramas, de 1.49 t ha-1, en la raíz de 0.76 t ha-1 y el carbono total acumulado, de 8.31 t ha-1. Se concluye que los valores manejados de las variables predictoras en la ecuación ajustada para estimar el carbono acumulado en la plantación de G. arborea varían por factores como la edad, las condiciones edafoclimáticas, las prácticas silvícolas y la densidad del arbolado.

Palabras clave Biomasa; manejo forestal; modelo matemático; plantación forestal; secuestro de carbono; servicios ambientales

Introduction

One of the options to mitigate climate change is carbon capture and storage because of its high potential to reduce greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (Benea, 2017). Carbon is absorbed by vegetation with photosynthesis and by the soil of ecosystems through the dynamics of carbon, which consists of the contributions of dead plant material, its loss by mineralization and its accumulation by humification; therefore, this component stores the largest amount of the element (IPCC, 2015).

The importance of the biomass of tree species in carbon storage has been recognized for several decades (Bohre et al., 2013); in this context, forest plantations are particularly valuable (Rasineni et al., 2011) and, even more, when fast-growing taxa are incorporated (Norby et al., 2005).

There is a potential for carbon uptake in biomass that could preserve carbon for decades in the wood. In addition, the use of biomass for energy purposes, from waste by-products from wood or crops, or from cultivated trees expressly intended for that purpose, could lead to a reduction in net greenhouse gas emissions if fossil fuels will be replaced (IPCC, 2015).

Mexico has an established area of commercial forest plantations of 270 000 ha of the main timber species, among which Gmelina arborea Roxb. occupies 24 061 ha-1 (Conafor, 2014).

At international level, several studies have been developed aimed at estimating the carbon stored in plantations of G. arborea with the use of allometric equations. In India, Bohre et al. (2013) calculated the accumulated carbon worked with the normal diameter (1.30 m) and the total height as predictive variables. In Colombia, Melo (2015) with models based on processes such as photosynthetically active radiation; temperature; the availability of water in the soil, among others, estimated the carbon stored. In that same country years later, Patiño et al. (2018) estimated the carbon stored according to the normal diameter (1.30 m) in a five years old. In Mexico, Cámara et al. (2013) determined the carbon stored in plantations four years old established in Tabasco. Although research has been carried out that evaluates the accumulated carbon of G. arborea for some regions, the storage potential of plantations established in the State of Mexico with this species still needs to be evaluated.

Therefore, the objective of the study described below was to estimate the carbon accumulated from mensuration variables and allometric equations in a Gmelina arborea plantation of different ages established in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The study was carried out in the commercial forest plantation (PFC, for its acronym in Spanish) of G. arborea located in the Las Piñas farm, Tlatlaya municipality, State of Mexico (Figure 1). The region is part of the Sierra Madre del Sur physiographic province and the Depression of the Balsas River subprovince (Inegi, 2009). The geographical coordinates of the area of interest are 18°22´ N and 100°04´ O; its average altitude is 694 m and has a slope of 40 %.

The trees are planted with a 3.10 m × 3.10 m spacing, which make up a density of 1 040 ha-1 trees in an area of eight hectares established in 2014. The types of soil in the area are Phaeozem (37.34 %), Regosol (34.5 %), Leptosol (10.1 %), Luvisol (10.1 %), Cambisol (6.5 %), Vertisol (0.76 %) and Fluvisol (0.31 %) (Inegi, 2009).

The climate is of the Aw1 type, warm subhumid with rains in summer and mean humidity of 70.88 %; and of the Aw2 type, warm subhumid with rains in summer, medium humidity (20.14 %), average annual temperature from 18 °C to 28 °C and annual rainfall, 1 000 mm to 1 500 mm (Inegi, 2009).

Mensuration data

Field data collection was carried out in 2016 and 2017, at 2.4, 2.6, 2.8 and 3 years after planting. A systematic sampling was used, through which eight permanent circular sampling plots with a radius of 11.28 m (400 m2) were established, which in total formed an inventoried area of 3 200 m2, corresponding to a sampling intensity of 4 %. In total, an inventory of 207 trees of the plantation was obtained, of which DAP data were recorded at 1.3 m (d1.3) by means of a Haglof Sweden® calipper, and the total height with the Nikon Forestry Pro® hipsometer. With the variables obtained in the inventory, data were obtained regarding the basimetric area and the stem volume with the cubication equation of Rodríguez and Castañeda (2014) (Equation 1), in addition to the trunk biomass, branch biomass, foliage biomass, total aerial biomass, carbon in the trunk, carbon in branches, carbon in foliage and total carbon of the tree, to estimate the carbon accumulated in the aerial part of the plantation 2.4, 2.6, 2.8 and 3.0 years.

Where:

V = Volume (m3)

D = Diameter (m)

h = Total height (m)

ff = Shape factor (0.46)

Estimation of aerial biomass (shaft and branches) and accumulated carbon

Biomass was quantified with a non-destructive sampling of the components of each Gmelina tree that make up the plantation (shaft and branches) (Ordóñez et al., 2001; López et al., 2016). For the aerial biomass, the equations proposed by Arias et al. (2011) for plantations of the same species in Costa Rica (Equations 2 and 3):

Where:

d = Normal diameter (cm)

B fuste = Stem biomass (kg)

B ramas = Branch biomass (kg)

Root biomass / total biomass ratio (R / T)

Fonseca et al. (2009) used the value of 0.10 of Mac Dicken (1997), which is a conservative value, to estimate the biomass of native species in plantations and secondary forests in Costa Rica.

Conversion Facto r(FC)

Conversion factor from ton of biomass (dry matter) to ton of carbon (tC). It is the of mass carbon per cent of wood; 50 % carbon; 41 %, oxygen; 6 %, hydrogen; 1 %, nitrogen and 2 %, ash, so the amount of carbon per ton of biomass (dry matter) is close to 500 kg (50 %) (Norverto, 2006). For the present study, the value of 0.4 was considered, which coincides with that referred for young Gmelina plantations (between 4 and 15 years) by Cubero and Rojas (1999) who calculated an interval between 0.32 and 0.4.

Statistical Analysis

The data were subjected to an analysis of variance (Anova) and comparison of Tukey means (<0.05) with the Statistica statistical program (Guisande et al., 2013) to determine the statistical difference in the PFC of G. arborea at different ages.

Results

Based on the forest inventories carried out in December 2016, February, April and June 2017, the PFC is established in an area of 8 ha, with the following characteristics:

Mensuration variables

The analysis of variance showed a high significant difference in the variables normal diameter and total height in the ages considered of the PFC with a probability (p <0.005). The comparison of Tukey means shows that the diameter of the plantation at different ages is statistically different (Table 1).

Table 1 Mean comparison of the mensuration data of Gmelina arborea Roxb. in Tlatlaya, Estado de México.

| Age (years) |

Normal diameter (cm) |

Height (m) |

Basimetric area (m2 ha-1) |

Stem volume (m3 ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 | 7.89 a | 5.68 a | 5.43 a | 15.09 a |

| 2.6 | 8.12 b | 5.80 b | 5.74 b | 16.31 b |

| 2.8 | 8.33 c | 5.92 c | 6.04 c | 17.54 c |

| 3.0 | 8.64 d | 6.22 d | 6.46 d | 19.63 d |

*Different letters in the columns mean significant differences (p<0.05).

The increase in normal diameter in the PFC between 2.4 and 3.0 years was 0.75 cm, with a significant difference (Table 1).

The total height of the trees also showed significant differences in the ages of measurement, with an increase of 0.54 m (Table 1).

With respect to the basimetric area, in addition to the significant differences in the ages, it recorded an increase of 1.03 m2 ha-1 from 2.4 to 3.0 years of planting.

The stem volume exhibited significant differences (p≤ 0.00) with a probability of (p <0.05) in the analysis of variance. The Tukey mean comparison test indicated significant statistical difference in ages and an increase of 4.55 m3 ha-1.

Stem, branches, root and total biomass

The stem biomass showed significant differences in the measurement ages; this component represents 72.10 %, 72.41 %, 72.67 % and 73 % of the biomass at 2.4, 2.6, 2.8 and 3.0 years, respectively, also showed an increase of 2.85 ton ha-1 (Table 2).

Table 2 Comparison of the means of stem, branches, root and total biomass of Gmelina arborea Roxb. established in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico.

| Age (years) |

Stem biomass (ton ha-1) |

Branch biomass (t ha-1) |

Aerial biomass (t ha-1) |

Root biomass (t ha-1) |

Total biomass (t ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 | 12.32 a | 3.21 a | 15.53 a | 1.55 a | 17.09 a |

| 2.6 | 13.19 b | 3.37 b | 16.56 b | 1.66 b | 18.21 a |

| 2.8 | 14.00 c | 3.51 c | 17.51 c | 1.75 c | 19.27 c |

| 3.0 | 15.17 d | 3.72 d | 18.89 d | 1.89 d | 20.78 d |

*Different letters in the columns mean significant differences (p<0.05).

Branch biomass showed significant differences in the different ages, which represents 18.81 %, 18.50 %, 18.24 % and 17.91 % of biomass at 2.4, 2.6, 2.8 and 3.0 years, respectively (Table 2).

Root biomass, which represents 9.09 % of the total woodland biomass, also registered significant differences (Table 2).

In general, the components of the total biomass (stem, branches and root) show a similar distribution in the different ages studied (Figure 2).

Stem, branches, root and total carbon

The result of the Tukey averages test for the carbon accumulated in the woodland components (stem, branches, aerial and total) in the four measurement ages showed significant differences except for the carbon accumulated in the root at 2.6 and 2.8 years, which showed no significant differences (Table 3). The stem stores 73.86 % of carbon accumulated at different ages, followed by the branches with 18.71 % and the root that stores carbon in a smaller proportion (7.43 %). It is observed that the accumulation of carbon in the components (stem, branches and root) has a similar distribution in the different measured ages of G. arborea trees (Figure 3).

Table 3 Comparison of means, carbon in stem, branches, root and total of Gmelina arborea Roxb. established in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico.

| Age (years) |

Stem (ton ha-1) |

Branches (t ha-1) |

Aerial (t ha-1) |

Root (t ha-1) |

Total (t ha-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.4 | 4.93 a | 1.29 a | 6.21 a | 0.16 b | 6.37 a |

| 2.6 | 5.28 b | 1.35 b | 6.62 b | 0.66 a | 7.29 b |

| 2.8 | 5.60 c | 1.41 c | 7.01 c | 0.70 a | 7.71 c |

| 3.0 | 6.07 d | 1.49 d | 7.56 d | 0.76 c | 8.31 d |

*Different letters in the columns mean significant differences (p<0.05).

Discussion

Based on the above, it was estimated that the G. arborea trees of the PFC presented an increase in normal diameter of 0.75 cm and an increase in height of 0.54 m, over a period of six months with significant differences; the total height is 6.22 m and the average DBH is 8.64 cm at 3.0 years, with a density of 1,040 ha-1 trees; Cámara et al. (2013) report a total height of 5.96 m and an average DBH of 11.04 cm in a four-year-old G. arborea plantation at a density of 906 ha-1 trees established at 20 masl in the state of Tabasco; described that the total height and the DAP influence the amount of biomass and carbon accumulated in the woodland; these results are different from those obtained in G. arborea established at 694 m; Jiménez (2016) recommends doing the first thinning in plantations of this species under an intensity of 50 to 25 % at three or four years and indicates that the objective is to favor the most vigorous trees, with good shape, which will be left to the final crop at the age of 10 to 12 years with a density of 277 to 416 ha-1 trees, respectively.

The biomass of the stem component was 72.54 %, branches 18.37 % and 9.09 % root in general in the plantation at the different ages evaluated, these results are consistent with those reported by Emanuelli and Milla (2014) who indicate that the fuste component contributes between 55-70 %, and the leaves component between 10-37 %, the distribution of biomass by components in G. arborea trees coincides with López et al. (2016), these authors obtained an average of 70.20 % in the stem component and 29.83 % in the branches component and state that the results showed significant statistical differences in plantations of Hevea brasiliensis Müell. Arg. of different ages, established in Tabasco, Mexico.

The carbon accumulated in the woodland components of the G. arborea plantation at three years was 6.07 t ha-1 in the shaft, 1.49 t ha-1 in the branches, 0.76 t ha-1 in the roots and 8.31 ton ha-1 of total accumulated carbon, this result lower than that of Cámara et al. (2013) who determined that the carbon stored is 15.54 t ha-1 in four-year-old G. arborea plantations with a density of 906 ha-1 trees in Tabasco; likewise, it differs from what was recorded by Melo (2015), who estimated with allometric equations and process-based models (photosynthetically active radiation, temperature, availability of water in the soil, etc.), which the forest plantation of G. arborea with a density of trees with 1100 six-year-old ha-1 trees established in Colombia at an altitude of 595 m, it stores 24.39 t ha-1; Patiño et al. (2018) estimated the carbon capture in the biomass of G. arborea in a Colombian plantation at an altitude of 250 m with a density of 1 111 ha-1 trees; their predictor variable was the DAP in the adjustment of allometric equations and they determined that at the age of five years the carbon stored is 41.6 t ha-1.

Several investigations have been carried out to estimate the carbon accumulated by adjusting allometric equations for different species, among which those carried out by Díaz et al. (2007) who adjusted a two-parameter equation in which they used as a predictor variable the normal diameter to estimate carbon in Pinus patula Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham., concluded that the carbon stored in the woodland components is distributed in the stem with 78.82 %, and in the branches and foliage component with 16.11 %. This distribution of carbon stored in the components is similar to that obtained in the plantation of G. arborea studied, since the stem stores 73.86 % and foliage 18.71 %.

Cámara et al. (2013) worked with equations to quantify the carbon stored in four-year Eucalyptus europhylla S. T. Blake plantations established in Tabasco with a 954 trees ha-1 density and in the Quercus oleoides Schltdl. et Cham savanna with a 258 trees ha-1 density; they determined that the carbon stored was 14.75 t ha-1 and 68.29 t ha-1 respectively.

The edafoclimatic characteristics of the study area of the plantation are some of the factors that condition the ability to store carbon, G. arborea established in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico at an altitude of 694 m, with a slope of 40 %, and with a density of 1 040 trees ha-1 the dominant soil is Phaeozem and the average rainfall of 1 000 mm.

Douterlungne et al. (2013) determined that the best predictors are the DAP and the diameter of the base in the adjustment of equations to estimate biomass and carbon in plantations for the purpose of restoration of Guazuma ulmifolia Lam., Trichospermum mexicanum (DC.) Baill., Inga vera Wild. and Ochroma pyramidale (Cav. ex Lam) Urb. with densities of 1 600 ha-1 trees established in Chiapas. They concluded that the plantations of T. mexicanum and G. ulmifolia are more efficient as carbon sinks and that the accumulation rates are not extrapolated to quantify the long-term stored carbon as indicated by Lugo et al. (2004); These authors asserted that the annual biomass and carbon accumulation rate declines with the age of the plantation as competition between trees increases.

Kongsager et al. (2013) estimated carbon stored in 21-year-old Theobroma cacao L. plantations with a density of 1 097 ha-1 trees, seven-year-old Elaeis guineensis Jacq with a density of 144 ha-1 trees, H. brasiliensis de 12 years and Citrus sinensis L. of 25 years with 266 ha-1 trees established in Ghana at an altitude of 114 m, used allometric equations in which the DBH and the diameter of the base were the predictor variables and conclude that the planting of H. brasiliensis has the greatest potential to store carbon (214 t ha-1) followed by T. cocoa with 65 t ha-1 carbon. These results are superior to those obtained in three-year G. arborea established in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico, and represents a potential to store carbon with adequate silvicultural management and practices.

López et al. (2016) determined the carbon stored in the aerial biomass of H. brasiliensis plantations established in Tabasco of different ages with the adjustment of allometric equations and that the carbon varies for each age. Thus, they estimated that in the five-year plantation, the carbon stored was 26.28 t ha-1 with a density of 491 trees ha-1, a result that differs from that obtained for G. arborea in Tlatlaya, which stores 8.31 ton ha- 1 at three years old.

Conclusions

The carbon accumulated in the G. arborea plantation established in Tlatlaya, State of Mexico at three years was 8.31 t ha-1, with a density of 1 040 ha-1 trees.

The distribution of biomass and carbon accumulated in the tree components of the plantation of G. arborea showed significant statistical difference for the different ages of measurement.

The values used of the predictive variables in the equation adjusted to estimate the carbon accumulated in the plantation studied of G. arborea may vary due to extrinsic and intrinsic factors such as age and forest density.

Acknowledgements

To the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología for the scholarship granted to the first author to carry out his Graduate studies.

REFERENCES

Arias, D., J. Calvo A., B. Richter and A. Dohrenbusch. 2011. Productivity, aboveground biomass, nutrient uptake and carbon content in fast-growing tree plantations of native and introduced species in the Southern Region of Costa Rica. Biomass and Bioenergy, 35(5): 1779-1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2011.01.009 (10 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Benea, L. M. 2017. Capture and storage of Carbon dioxide: a method for countering climatic changes. In : IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 163(1): 012045. Doi:10.1088/1757-899X/163/1/012045. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/163/1/012045/pdf (20 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Bohre, P., O. P. Chaubey and P. K. Singhal. 2013. Biomass accumulation and carbon sequestration in Tectona grandis Linn. f. and Gmelina arborea Roxb. International Journal of Bio-science and Bio-technology 5(3): 153-174. https://www.earticle.net/Article/A207142 (5 de marzo de 2019). [ Links ]

Cámara, C. L. del C., C. Arias M., J. L. Martínez S. y O. Castillo A. 2013. Carbono almacenado en selva mediana de Quercus oleoides y plantaciones de Eucalyptus urophylla y Gmelina arborea en Huamanguillo, Tabasco. In: Pellat, F. P., W. G. Julio, B. Maira y V. Saynes (eds.). Estado actual del conocimiento del ciclo del carbono y sus interacciones en México: Síntesis a 2013. Colegio de Posgraduados, Universidad Autónoma de Chapingo, Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey. Texcoco, Estado de México. 702 p. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Xochitl_Cruz-Nunez2/publication/263043104_42_Incendios_forestales_carbono_negro_y_carbono_organico_en_Mexico_2000_-_2012/links/0f3175399dd7314471000000/42-Incendios-forestales-carbono-negro-y-carbono-organico-en-Mexico-2000-2012.pdf (10 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2014. Principales especies maderables establecidas en PFC por entidad federativa en el periodo 2000-2014. Coordinación General de Producción y Productividad. Gerencia de Desarrollo de Plantaciones Forestales Comerciales. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. http://www.conafor.gob.mx:8080/documentos/docs/43/6019Principales%20especies%20maderables%20establecidas%20en%20PFC%20por%20Entidad%20Federativa%20en%202000%20-%202014.pdf (18 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Cubero, J. y S. Rojas, 1999. Fijación de carbono en plantaciones de melina (Gmelina arbórea Roxb.), teca (Tectona grandis L. f.) y pochote (Bombacopsis quinata Jacq.) en los cantones de Hojancha y Nicoya, Guanacaste, Costa Rica. http://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:taRWtUkKV4QJ:cglobal.imn.ac.cr/Pdf/mitigacion/Estudio%2520sobre%2520Fijación%2520de%2520Crbono%2520en%2520%Plantaciones.pdf (15 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Díaz F., R., M. Acosta-M., F. Carrillo A., E. Buendía R., E. Flores A. y J. D. Etchevers B. 2007. Determinación de ecuaciones alométricas para estimar biomasa y carbono en Pinus patula Schl. et Cham. Madera y Bosques 13(1): 25-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.21829/myb.2007.1311233 (12 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Douterlungne, D., A. M. Herrera G., B. G. Ferguson, I. Siddique y L. Soto P. 2013. Ecuaciones alométricas para estimar biomasa y carbono de cuatro especies leñosas neotropicales con potencial para la restauración. Agrociencia 47(4): 385-397. http://www.scielo.org.mx/pdf/agro/v47n4/v47n4a7.pdf (12 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Emanuelli A., P. y F. Milla A. 2014. Construcción de funciones de volumen. Volumen, Biomasa y Carbono Forestal. Nota Técnica Núm. 4: 4: http://www.reddccadgiz.org/monitoreoforestal/docs/mrv_2099067706.pdf (12 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Fonseca G., W., F. Alice G. y J. M. Rey B. 2009. Modelos para estimar la biomasa de especies nativas en plantaciones y bosques secundarios en la zona Caribe de Costa Rica. Bosque 30(1): 36-47. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0717-92002009000100006 (12 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Guisande G., C., A. Vaamonde L. y A. Barreiro F. 2013. Tratamiento de datos con R, Statistica y SPSS. Editorial Díaz de Santos. Madrid, España. 997 p. http://blog.utp.edu.co/estadistica/files/2017/09/TRATAMIENTO-DE-DATOS-CON-R-ESTATISTICA-Y-SPSS.pdf (18 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Panel Intergubernamental de Cambio Climático (IPCC). 2015. Cambio climático 2014 Informe de síntesis. In: Pachauri, R. K. y L. A. Meyers (eds.). Contribución de los Grupos de trabajo I, II Y III al Quinto Informe de Evaluación del Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático. Ginebra Suiza: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/SYR_AR5_FINAL_full_es.pdf (15 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (Inegi). 2009. Prontuario de información geográfica municipal de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Tlatlaya, Estado de México. Clave geoestadística 15105. http://www3.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/app/mexicocifras/datos_geograficos/15/15105.pdf (20 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Jiménez P., L. P. 2016. El cultivo de la Melina (Gmelina arborea Roxb.) en el trópico. 125 p Editorial Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE. Sangolquí, Ecuador. http://repositorio.espe.edu.ec/jspui/handle/21000/11687 (12 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Kongsager, R., J. Napier and O. Mertz. 2013. The carbon sequestration potential of tree crop plantations. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 18(8): 1197-1213. Doi 10.1007/s11027-012-9417-z. [ Links ]

López R., L. Y., M. Domínguez D., P. Martínez Z., J. Zavala C., A. Gómez G. y S. Posada C. 2016. Carbono almacenado en la biomasa aérea de plantaciones de hule (Hevea brasiliensis Müell. Arg) de diferentes edades. Madera y Bosques 22 (3): 49-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.21829/myb.2016.2231456 (12 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Lugo, A. E., W. L. Silver and S. Molina C. 2004. Biomass and nutrient dynamics of restored neotropical forests. In: Wieder, R. K., M. Novák and M. A. Vile. (eds.). Biogeochemical Investigations of Terrestrial, Freshwater, and Wetland Ecosystems across the Globe. Springer, Dordrecht. pp. 731-746. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-007-0952-2_50 (20 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Mac Dicken, K. 1997. A guide to monitoring carbon storage in forestry and agroforestry projects. Forest Carbon Monitoring Program. Winrock International Institute for Agricultural Development (WRI). http://www.winrock.org/REEP/PUBSS.html (17 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Melo C., A. O. 2015. Modelación del crecimiento, acumulación de biomasa y captura de carbono en árboles de Gmelina arborea Roxb., asociados a sistemas agroforestales y plantaciones homogéneas en Colombia. Tesis de Doctorado Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias. Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Sede Medellín. Medellín, Colombia. 166 pp. http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/50068 (25 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Norby, R. J., E. H. DeLucia, B. Gielen, C. Calfapietra, C. P Giardina, J. S King and P. De Angelis. 2005. Forest response to elevated CO2 is conserved across a broad range of productivity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102(50): 18052-18056. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0509478102 (25 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Norverto, C. A. 2006. La fijación de CO2 en plantaciones forestales y en productos de madera en Argentina. 13 p. Editorial GRAM. Buenos Aires, Argentina. 13 p. [ Links ]

Ordóñez, J. A., B. H. J de Jong y O. Masera, 2001. Almacenamiento de carbono en un bosque de Pinus pseudostrobus en Nuevo San Juan, Michoacán. Madera y Bosques 7 (2): 27-47. https://doi.org/10.21829/myb.2001.721310 (10 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Patiño F., S. L. N. Suárez S., H. J. Andrade C., y M. A Segura M. 2018. Captura de carbono en biomasa en plantaciones forestales y sistemas agroforestales en Armero-Guayabal, Tolima, Colombia. Revista de Investigación Agraria y Ambiental 9 (2). https://doi.org/10.22490/issn.2145-6453 (12 de febrero de 2019). [ Links ]

Rasineni, G. K., A. Guha and A. R. Reddy. 2011. Responses of Gmelina arborea, a tropical deciduous tree species, to elevated atmospheric CO2: growth, biomass productivity and carbon sequestration efficacy. Plant Science 181(4): 428-438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.07.005 (18 de enero de 2019). [ Links ]

Rodríguez A., L. G. and A. M. Castañeda G. 2014. Carbon capture in three forest species in Meta Department. Revista Científica Guarracuco, 18(29). http://revistas.unimeta.edu.co/index.php/rc_es_guarracuco/article/view/67/277 (05 de marzo de 2019). [ Links ]

Received: June 13, 2019; Accepted: August 30, 2019

texto em

texto em