Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.10 no.51 México 2019

https://doi.org/10.29298/rmcf.v10i51.295

Articles

Identification and initial growth of forest species used for curing Virginia tobacco

1Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria - AGROSAVIA, C.I. Colombia.

In Colombia, Virginia tobacco producers (Nicotiana tabacum L.) use artisan kilns based on the combustion of firewood and charcoal for the curing of the leaves. This study aimed to mitigate the threat of deforestation by identifying which forest species are used and quantifying their gross combustion heat (CCB) from samples collected at the sites of usage, at a first stage. Afterwards, in a second phase, the initial growth of eight native and exotic species were evaluated, establishing two experiments in the municipalities of Soata (Boyacá), Enciso and San José de Miranda (Santander). The experimental design used was of randomized complete blocks with three replicates (species as treatments). As a result, Eucalyptus sp (57 %), Pithecellobium dulce (48 %), Escallonia pendula (12 %) and Manclure tinctoria (9 %) were the most used species. As for CCB, E. pendula (18.8 MJ kg-1) had the highest value, while Citrus sinensis (12.5 MJ kg-1) had the lowest value. After 150 days of establishment, E. grandis and E. globulus had a larger diameter of stem (13.7 mm) and height (132.2 cm), while Pithecellobium dulce and Pseudosamanea guachapele were the lowest, with 6.5 mm and 40.9 cm each one. Findings shows a higher growth of the exotic species for the three localities. Furthermore, around 20 multipurpose species showed a great variation in their caloric value.

Key words: Gross combustion heat; deforestation; dendroenergetic species; Nicotina tabacum L.; Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth; calorific value

En Colombia, los productores de tabaco Virginia (Nicotiana tabacum L.) emplean hornos artesanales basados en la combustión de leña y carbón mineral para el curado de las hojas. Con el objetivo de mitigar la amenaza por deforestación, en una primera fase se identificaron las especies forestales usadas y se cuantificó su calor de combustión bruto (CCB), a partir de muestras recolectadas en los sitios de utilización. En la segunda fase, se evaluó el crecimiento inicial de ocho especies nativas y exóticas, mediante dos experimentos en los municipios de Soata (Boyacá), Enciso y San José de Miranda (Santander). El diseño experimental usado fue de bloques completos al azar con tres repeticiones (especies como los tratamientos). Eucaliptus sp (57 %), Pithecellobium dulce (48 %), Escallonia pendula (12 %) y Manclura tinctoria (9 %) fueron los taxones más utilizados. En cuanto al CCB, E. pendula (18.8 MJ kg-1) presentó el mayor valor y Citrus sinensis (12.5 MJ kg-1), el menor. Transcurridos 150 días desde el establecimiento, E. grandis y E. globulus evidenciaron un diámetro de tallo superior (13.7 mm) y altura (132.2 cm); mientras Pithecellobium dulce y Pseudosamanea guachapele fueron los de menor porte, 6.5 mm y 40.9 cm. Se constató más crecimiento de las especies exóticas para las tres localidades. Además, alrededor de 20 taxa multipropósito presentaron amplia variación en su valor calórico.

Palabras clave: Calor de combustión bruto; deforestación; especies dendroenergéticas; Nicotina tabacum L.; Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth; valor calórico

Introduction

Although in the long term the worldwide demand of tobacco generates many questions due to the health risks that its consumption entails, its production is the means of sustenance of a large number of families in the underdeveloped countries of Africa and Latin America (Siddiqui, 2001; Jimu et al., 2017). In Colombia, this crop has over a century of history, and, at the national level, approximately 6 000 ha of land are planted with tobacco (MADR, 2016). The department of Santander represents 40 % of this area, followed by Huila and Boyacá (36 %) (MADR, 2016).

For drying the tobacco leaves, the small producers in the Third World countries use artisanal kilns fueled with firewood (Siddiqui, 2001; Jimu et al., 2017). This flue cured or “barn-style” drying method is the most common in Santander, where Virginia tobacco is produced for the manufacture of cigarettes (Cerquera and Pastrana, 2014; MADR, 2016).

Given their artisanal design, these kilns, fueled with firewood or charcoal, have a very low efficiency level (below 5 %); furthermore, they have unstable temperatures above the recommended values and an uneven dehydration of the leaves (Cerquera and Pastrana, 2014; Munanga et al., 2014).

Considerations regarding the preservation of the native forests and the environmental pollution in tobacco-producing regions were unattended for several decades (Jimu et al., 2017). I.e., according to the estimates, between 1.2 and 2.5 million hectares of forests are required every year worldwide for the purpose of curing tobacco; this represents 2 to 4 % of the global deforestation (Hu and Lee, 2015). Due to environmental restrictions for coal combustion and to the higher cost of other systems for the small tobacco producers, it may be assumed that firewood will continue to be the main fuel.

Although in Colombia approximately 60 million hectares (52 % of the country’s territory) are covered with forests, deforestation rates are high (Armenteras et al., 2013). Field identification and evaluation of the species utilized in traditional tobacco kilns may contribute to reforestation plans and to the development of technologies for improving their efficiency.

Based on the above, the present study had the following objectives: 1) to identify the species and quantify their calorific power when utilized as firewood at the use sites, and 2) to evaluate the initial in-field growth of eight native and exotic forest species with a high dendroenergetic potential.

Materials and Methods

The study comprised two phases, conducted during the years 2010 and 2011. In the first phase, the species utilized as firewood in traditional kilns were identified, and their gross combustion heat was quantified; the second phase corresponded to the assessment of eight forest taxa with a high dendroenergetic potential in three municipalities of Boyacá and Santander.

Identification and calorific power of the species

From March to May, 2010, the Virginia tobacco producing areas of Capitanejo, Concepción, Enciso, Málaga, Macaravita, San José de Miranda, San Miguel and San José de Miranda (Santander), and Boavita, Covarachia, El Espino, Tipacoque, San Mateo and Soata (Boyacá) municipalities, whose altitude ranges between 1 500 and 2 000 masl, were visited. The tree taxa utilized for curing tobacco through semi-structured surveys; the sampled population consisted of the 26 producers that best represent these areas, as suggested by the community and by the tobacco-producing companies. The percentage of use (% U) of a particular species, was calculated according to Equation 1:

In addition, the information consolidated in the diagnose included the most precocious forest species, species with a low smoke emission and species used as domestic fuel; the cost and provenance of the firewood; the land tenure structure of the plot and the size of the tobacco plantation, and the tobacco curing infrastructure and process, among other socioeconomic aspects.

Furthermore, samples of flowers, leaves and stems of each taxon were collected from the rural properties, pressed and fixed on kraft paper in order to corroborate their identification in the wood laboratory of the Universidad Industrial de Santander (UIS) (UIS), Sede Málaga (Industrial University of Santander (UIS), Málaga Headquarter).

In order to characterize the treatments according to their calorific power (Table 1), 20 logs (one per species) were obtained directly from the traditional kilns and transformed into (10 cm long × 4 cm wide) test specimens, which were dried and processed into sawdust. The samples (20 g) were subsequently analyzed using the standard gross combustion heat method (GCH), with a calorimetric pump (Parr 6200), according to the norm ASTM D 240 (ASTM, 2007), at the facilities of the Instituto Colombiano del Petróleo (Colombian Institute of Petroleum), in the Piedecuesta municipality, Santander.

Table 1 Native and exotic species used as firewood for curing tobacco in Santander and Boyacá, and their gross combustion heat.

| Scientific name | Common name | GCH (MJ kg-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC. | Cuji | 16.59 3 |

| Psidium guajava L. | Guava | 18.60 4 |

| Quercus humboldtii Bonpl. | Oak | 14.40 2 |

| Guazuma ulmifolia Lam. | Bay cedar | 15.96 4 |

| Cardiospermum corindum L. | Balloon vine | 17.32 1 |

| Manclura tinctoria (L.) D. Don ex Steud. | Dyer’s mulberry | 16.83 4 |

| Eucaliptus grandis W. Hill | Rose gum | 17.55 2 |

| Eucaliptus globulus Labill | Tasmanian Bluegum | 15.91 6 |

| Duranta mutisii L.f. | Hawthorn | 15.78 1 |

| Myrsine guianensis (Aubl.) Kuntze | Rapanea | 17.42 2 |

| Escallonia pendula (Ruiz & Pav.) Pers | Loqueto | 18.77 2 |

| Calliandra pittieri Standl. | Carbonero | 17.43 5 |

| Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth | Huamuche | 17.42 4 |

| Fraxinus chinensis Roxb. | Chinese ash | 16.01 6 |

| Pseudosamanea guachapele (Kunth) Harms | Igua | ** |

| Casuarina equisetifolia L. | Australian pine | 17.94 5 |

| Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit | Leucaena | 17.12 5 |

| Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck | Orange tree | 12.55 |

| Salix humboldtiana Willd. | Humboldt’s willow | ** |

| Weinmannia tomentosa L.f | Encenillo | ** |

*Gross combustion heat; **No test was conducted. Municipality of origin of the material: 1 = San José de Miranda; 2 = Concepción; 3 = Capitanejo; 4 = Enciso en Santander; 5 = Boavita; 6 = Soata in Boyacá.

Initial growth of eight tree species with dendroenergetic potential

Once the surveys were conducted, two experiments were established in San José de Miranda and Enciso municipalities, department of Santander and Soata, department of Boyacá (Figure 1). The selected species stand out to a greater or lesser extent for their dendroenergetic potential, for the shade that they cast over the grasslands, for serving as living fences, and for being an additional source of food for animals and humans (Pérez et al., 2011; Olivares et al., 2011; Pinto et al., 2014; Díaz et al., 2014; Chitra and Balasubramanian, 2016; Márquez et al., 2017). The treatments were prioritized with the participation of the local communities.

Municipio = Municipality; Parcela = Plot; Coordenada geográfica = Geographic coordinate; Altitud = Altitude; Unidad experimental = Experimental unit;

Figure 1 Geographic location of the established plots and field arrangement of the experiment (experimental unit).

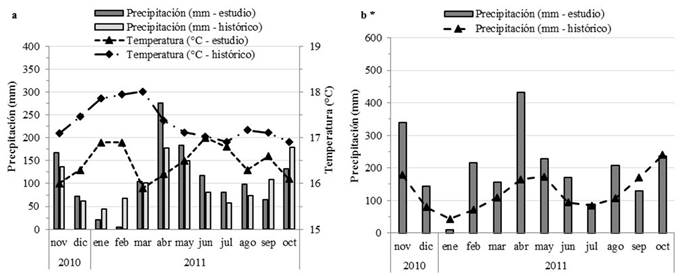

The study region has a tropical equatorial (Af) climate, according to Köppen’s classification; the rainfalls are concentrated in two periods: from April to May and from September to October; i.e., the region has a bimodal season regime. The utilized records of monthly temperatures and precipitations obtained through the Instituto de Hidrología, Meteorología y Estudios Ambientales, IDEAM (Institute of Hydrology, Meteorology and Environmental Studies) located at a distance of 5 to 10 km of the plots, were historical and specific for the study period (Figure 2).

Temperatura = Temperature; Precipitación = Precipitation

*No temperature record was available.

Figure 2 Climate rainfall and precipitation records and monthly temperatures of the study period (Dec_2010 to Apr/2011) and historical records (1979-2009 series) for San José de Miranda and Enciso (a), and Santander and Soata (b), Boyacá municipalities.

As for the soils, they are characterized by medium to low contents of organic matter, exchangeable bases and available phosphorus; and neutral to lightly alkaline pH levels. According to the soil taxonomy of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and FAO, they are classified as ustropepts, ustorthents and dystropepts (León and Coronado, 2003; Rodríguez et al., 2012).

Seedling production

The seeds were commercially acquired and sown in plastic trays with peat moss. Once they attained a mean height of 5 to 6 cm, they were transplanted to (17 cm long × 12 cm wide) plastic bags that contained a mix of substrate consisting of earth, sand and vermicompost (v:v:v: 3:1:1), and were cultivated in an agricultural nursery with 65 % shade. The production of the seedlings started in June, 2010, at the facilities of the La Suiza of the Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria (AGROSAVIA), (Research Center of the Colombian Corporation for Research on Agriculture and Livestock) in Rionegro municipality (7°22’12” N; 73°10’39” W; 532 masl) for Guazuma ulmifolia Lam., Leucaena leucocephala (Lam.) de Wit, Psidium guajava L., Pithecellobium dulce (Roxb.) Benth and Pseudosamanea guachapele (Kunth) Harms; Eucalyptus grandis W. Hill was produced at UIS, Málaga (6°41’58” N; 72°43’58” W; 2 335 masl).

Eucaliptus globulus Labill and Acacia mangium Willd seedlings were obtained from a commercial nursery located in Málaga municipality. Finally, all the plants were taken to the field in November, 2010, at five months of age, after (30 cm wide x 30 cm deep) holes had been manually dug in each site, and planted in staggered rows or in a triangular arrangement (3 m x 3m). The application of 10 g of polyacrylamide hydrogel (soil conditioner) per seedling at the time of the transplant was a common practice. No irrigation systems were installed on the plots.

The management of the plots during the evaluation period included weed control with scythes 60 and 100 days after the in-field establishment and three fertilizations. The first was carried out at 50 after the establishment, with the application of 2 kg of vermicompost per seedling; the other two were cover fertilizations, each with 30 of diammonium phosphate (18 % N; 46 % P2O5), 60 and 120 days after the establishment. No symptoms due to pest or phytosanitary attacks were observed.

Field evaluation and statistical design

Two experiments were conducted on four tall forest species in each locality (in San José de Miranda, Enciso and Soata municipalities) ―E. grandis, E. globulus, A. mangium and P. guachapele―, and on an equal number of short forest species ―P. guajava, P. dulce, G. ulmifolia and L. leucocephala. The treatments were the various species. Given the irregular topography in the field, a randomized complete block design was used with three replications, and with 25 seedlings as experimental unit.150 days after the establishment, measuring the stem diameter (at ground level) with a caliper gauge (Discover Meter ISO), and the height with a flexometer (Stanley PowerLock). Four central seedlings were selected from each experimental unit in order to collect the data (Figure 1).

Statistical analysis

The data were subjected to a variance analysis, and the means of the treatments were compared with a Tukey’s test where there were differences (p<0.05), using the Statistical Analysis System software, version 9.3 (SAS, 2013). At the beginning, a variance analysis was carried out by locality and species size. After verifying the homoscedasticity of the variances, the locality effect in each assay was evaluated through a statistical procedure for the analysis of joint experiments, (Banzatto and Kronka, 2006). The information from the surveys was consolidatated in a database for its descriptive analysis.

Results and Discussion

The availability of a particular species was proven to depend on three aspects: 1) offer by the small foresters of cold areas (> 2 000 masl); 2) utilization of the trees scattered within the tobacco-producing plots as living fences, and 3) firewood collected from Chicamocha, Servita and Tunebo rivers. Furthermore, we identified 20 multipurpose species used (Table 1) to fuel the kilns, among which E. globulus and E. grandis (57 %) are the most prominent, due to their easy availability and because of their provenance from the Concepción, Málaga and San Miguel municipalities, in Santander, and Soata, Boavita, El Espino and Susacón, in Boyacá.

The tropical region includes a wide variety of native taxa with a high timber potential for the recuperation of natural forests and the preservation of their biodiversity. However, silviculture in the country has focused on only a few species, usually on Eucaliptus spp. and Acacia spp. (Breugel et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2016). The present study proved Eucaliptus spp. to be the most frequently used. This accounts for the existence of small plantations in temperate and cold areas very close to the tobacco-producing zones, which makes them easy to acquire, compared to mineral coal obtained from more distant municipalities. Other utilized taxa were P. dulce (48 %), E. pendula (12 %), M. tinctoria (9 %), C. pittieri (8 %) and F. chinensis (8 %). In general, all the logs with a medium length of 50 to 80 cm and thickness of 0.5 to 20 cm are utilized in the process of curing tobacco 20 to 30 days after felling.

The residues of the materials left from the fires are incorporated to the prairies and to the crops after at least one year of decay.

The GCH ranged between 12.55 MJ kg-1, for C. sinensis, and 18.77 MJ kg-1, for E. pendulla. Its mean value for the rest of the species was 16.8 MJ kg-1 (Table 1). Pérez et al. (2011) obtained values of 17 to 20 MJ kg-1 for plantations of various eucalyptus species. The lower figures estimated in this study for E. globulus (15.91 MJ kg-1) and E. grandis (17.55 MJ kg-1) may be due to the acquisition of lower-quality or precocious logs by the producers.

Likewise, a study conducted in the Reserva de la Biosfera Selva El Ocote, (El Ocote Rainforest Biosphere Reserve) in Chiapas, Mexico, concluded that there was no relationship between the firewood value index (a combination of the calorific content, wood density, moisture content and amount of ash) and the preference for the 39 species utilized by the inhabitants, as only six taxa attained high values. The authors mention that the availability, closeness to home and viability may influence the choice of the species used for firewood (Márquez et al., 2017).

In regard to the initial growth, the variance analysis evidenced a significant effect for the species-locality interaction on the variables stem diameter and height, both in tall (valor p=0.0183 y p=0.0137, respectively) and short species (value p=0.0421 and p=0.0001, respectively). 150 days after the establishment, E. grandis and E. globulus exhibited the best results for stem diameter, compared to the two other species, in three localities; however, their individual behavior was lower in the municipality of Soata, with 11.7 and 9.2 mm, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2 Stem diameter for eight forest species in three municipalities of Santander and Boyacá, 150 days after the establishment.

| Locality | Tall species (mm) | |||

| E. grandis | E. globulus | P. guachapele | A. mangium | |

| San José de Miranda | 15.9 a AB | 12.0 ab AB | 6.7 c A | 8.5 bc A |

| Enciso | 19.1 a A | 14.2 b A | 9.4 c A | 7.8 c A |

| Soata | 11.7 a B | 9.2 ab B | 7.3 b A | 6.9 b A |

| Locality | Short species (mm) | |||

| P. guajaba | P. dulce | G. ulmifolia | L. leucocephala | |

| San José de Miranda | 9.7 a A | 8.2 a A | 9.2 a A | 10.1 a A |

| Enciso | 9.6 a A | 5.4 b A | 11.9 a A | 11.0 a A |

| Soata | 7.7 bc A | 5.9 c A | 10.7 ab A | 11.9 a A |

Means followed by the same low-case letter in the same row and by the same capital letter in the same column do not differ, according to Tukey’s test. * p<0.05.

P. guchapele and A. mangium exhibited the lowest values for this variable, although without significant differences between localities. Only San José de Miranda showed no statistical differences between the four short species. In Soata (5.4 cm) and Enciso (5.9 cm), P. dulce had lower values than the other taxa. No significant effect of the locality factor was observed (value of p=0.7830) (Table 2).

The tall species P. guachapele and A. mangium exhibited greater heights than the other two taxa in the three assessed localities. In Enciso, E. grandis and E. globulus exhibited their best performance, with 205.6 cm and 153.3 cm, respectively; these values were higher than those of the localities of San José de Miranda and Soata. P. guachapele and A. mangium registered no differences between the three municipalities (Table 3).i.e., the exotic taxa showed the greatest growth in the three localities.

Table 3 Plant height for eight forest species in three municipalities of Santander and Boyacá, 150 days after establishment.

| Locality | Tall species (cm) | |||

| E. grandis | E. globulus | P. guachapele | A. mangium | |

| San José de Miranda | 115.9 a B | 94.3 a B | 32.9 b A | 50.2 b A |

| Enciso | 205.6 a A | 153.5 b A | 46.7 c A | 55.7 c A |

| Soata | 122.5 a B | 101.1 a B | 43.15 b A | 51.2 b A |

| Locality | Short species (cm) | |||

| P. guajaba | P. dulce | G. ulmifolia | L. leucocephala | |

| San José de Miranda | 66.3 ab A | 50.2 ab AB | 34.5 b C | 79.8 a A |

| Enciso | 74.5 b A | 64.4 b A | 72.7 b A | 118.9 a A |

| Soata | 43.8 b B | 37.1 b B | 57.1 b B | 123.0 a A |

Means followed by the same low-case letter in the same row and by the same capital letter in the same column do not differ, according to Tukey’s test. * p<0.05.

Given the high vigor, the broad adaptability and the short period until the forest exploitation of eucalyptus, according to Farias et al. (2016), this taxon may be assumed to have a greater acceptance in the studied tobacco-producing areas. However, the use of introduced species must be analyzed in depth. For example, the poor survival of Eucalyptus plantations located in southern China and, to a lesser extent, the emergence of twelve native tree species, are due to the allelopathic effects of their roots. Conversely, their topsoil promoted the initial growth of most of the taxa; therefore, differentiated management strategies are advisable (Zhang et al., 2016).

The lower response in height for native species, may be due to their incipient domestication status and to lack of knowledge of their interaction with the environment, which hinders implementation of management techniques. However, they have other attractive ecological and environmental attributes.

In degraded soils of the southern Amazon, Tachigali vulgaris L.f. Gomes da Silva & H.C. Lima exhibited a greater survival, a growth rate thrice as fast and a topsoil production twice higher than those of E. urophylla and E. grandis. Furthermore, it suppressed the invasive species (Farias et al., 2016). Another positive experience is cited in a joint plantation of E. grandis and P. guachapele on sandy soils, where the amount of N contributed to the soil and the mineralization rate of the residues increased significantly, even with a small contribution (11 % of the total deposited) of the legume (Carvalho et al., 2004).

L. leucacephala is a forage species with a high protein content for the nutrition of ruminants and birds in grasslands, or as living fences, as is common in small tobacco farmsteads with a peasant economy. Pinto et al. (2014) assessed biomass production in Leucana collinsi Britton & Rose, with records of up to 2 490 kg ha-1 of dry matter, 120 days after planting. P. guachapele, selected for this study, stands out for its high protein and fiber contents (18.9 % and 24.4% based on the dry weight, respectively) in its leaves; therefore, it is also recommended as a dietary supplement (Chitra and Balasubramanian, 2016).

In Colombian long-haired sheep under grazing conditions, supplementation with G. ulmifolia, a tree species of the dry tropical forest, contributed to the maintenance and increase of weight gain, in contrast to the treatment without supplements, especially during the dry season (Díaz et al., 2014). These additional qualities are of interest for the tobacco producers, because in Santander the sheep and goat chain has gradually become established, although its limiting factor is the low availability of water.

The results of the present study indicated a greater initial vigor of forest species for the edaphoclimatic conditions of the municipality of Enciso, without very marked differences between the localities of Soata and San José de Miranda. According to Breugel et al. (2011), out of 47 native and 2 exotic tree species, 35 % exhibited differences in the final growth, in sites of high or low fertility and in humid or dry sites of Panama, two years after planting.

Likewise, the strong correlation (r= 0.62 to 0.91) of the climate conditions (temperature, rainfalls and accumulated solar radiation) on the growth in height was validated in E. urophylla × E. grandis (Elli et al., 2017). On the other hand, selection and a successful protocol for the obtainment of high-quality seedlings during the nursery phase are crucial to restoration programs with native species, as documented by Lu et la. (2016).

Conclusions

Tobacco growers of Boyacá and Santander use approximately 20 multipurpose species with different caloric values (12.5 to 18.8 MJ kg-1). The species most frequently used are Eucaliptus spp. (57 %), Pithecellobium dulce (48 %), Escallonia pendula (12 %) and Manclura tinctoria (9 %). In general, the tall exotic taxa E. grandis and E. globulus exhibit a higher growth (mean height of 132.2 cm) than the native species P. guachapele (mean height of 40.9 cm). Finally, these studies must be continued until the forest exploitation and they must characterize the dendroenergetic and ecological potential of the evaluated species.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to forest engineers Fabio Ortiz, for his support in field work and Victoriano Vargas, for the botanical identification of the specimens. This study is part of the project “Utilización de fuentes dendroenergéticas para el mejoramiento de la curación del tabaco Virginia en los departamentos de Santander, Boyacá y Huila” (“Utilization of dendroenergetic sources for the improvement of the curing of Virginia tobacco in the departments of Santander, Boyacá and Huila”), conducted by AGROSAVIA with resources from the Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural de Colombia (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development of Colombia), through an agreement with UIS, Unisangil, Philip Morris International and British American Tobacco Colombia SAS.

REFERENCES

Armenteras, D., E. Cabrera, N. Rodríguez and J. Retana. 2013. National and regional determinants of tropical deforestation in Colombia. Regional Environmental Change 13 (6): 1181-1193. [ Links ]

America Society of Testing Materials (ASTM). 2007. ASTM International: Heat of Combustion of Liquid Hydrocarbon Fuels by Bomb Calorimeter Standard Test West Conshohocken, PA USA. 9 p. [ Links ]

Banzatto, D. e S. N. Kronka. 2006. Experimentação agrícola. Ed. FUNEP - UNESP. Jaboticabal, Brasil. 237 p. [ Links ]

Breugel, M., J. S. Hall, D. Craven, T. G. Gregoire, A. Park, D. Dent, M. H. Wishnie, E. J. Mariscal, D. Deago, N. Ibarra, N. Cedeño and M. Ashton. 2011. Early growth and survival of 49 tropical tree species across sites differing in soil fertility and rainfall in Panama. Forest Ecology and Management 261 (10): 1580-1589. [ Links ]

Carvalho, F., A. A. Franco, M. Pereira, E. F. Cameiro, L. E Dias, S. Faria e B. Rodrigues. 2004. Dinâmica da serapilheira e transferência de nitrogênio ao solo, em plantios de Pseudosamanea guachapele e Eucalyptus grandis. Pesquisa Agropecuaria Brasileira 39 (6): 597-601. [ Links ]

Cerquera, N. E. y E. Pastrana. 2014. Evaluación de la eficiencia energética en los hornos tradicionales de curado de tabaco. EIA 11 (22): 155-165. [ Links ]

Chitra, P. and A. A. Balasubramanian. 2016. Study on chemical composition and nutritive value of Albizia tree leaves as a livestock feed. International Journal of Science, Environment and Technology 5(6): 4638-4642. [ Links ]

Díaz, V., J. Hemberg e R. Castañeda. 2014. Desempeño animal de ovinos de pelo colombianos, suplementados con especies arbóreas del bosque seco tropical. Revista Colombiana de Ciencia Animal 7 (1): 82-88. [ Links ]

Elli, E., B. O. Caron, A. Behling, E. Eloy, V. Queiróz, F. Schwerz and J. R. Stolzle. 2017. Climatic factors defining the height growth curve of forest species. Italian Society of Silviculture and Forest Ecology 10: 547-553. [ Links ]

Farias, J. B., L. Marimon, F. Silva, F. R. Petter, P. Andrade, S. Morandi and B. M Marimon. 2016. Survival and growth of native Tachigali vulgaris and exotic Eucalyptus urophylla × Eucalyptus grandis trees in degraded soils with biochar amendment in southern Amazonia. Forest Ecology and Management 368: 173-182. [ Links ]

Hu, T. and A. H. Lee. 2015. Tobacco control and tobacco farming in African countries. Journal of Public Health and Policy 36 (1): 41-51. [ Links ]

Jimu, J., L. Mataruse, L. Musemwab and I. Nyakudya. 2017. The miombo ecoregion up in smoke: The effect of tobacco curing. World Development Perspectives 5: 44-46. [ Links ]

León, C. E y R. A. Coronado. 2003. Cultivos de cobertura: una alternativa para la agricultura sostenible en las provincias de Guanetá y Comunera y de García Rovira en Santander - Boletín técnico. Corporación Colombiana de Investigación Agropecuaria. Bucaramanga, Colombia. 50 p. [ Links ]

Lu, Y., S. Ranjitkar, J.-C. Xu, X.-K. Ou, Y.-Z. Zhou, .J.-F. Ye, X.F. Wu, H. Weyerhaeuser and J. He. 2016. Propagation of native tree species to restore subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests in SW China. Forests 7 (1): 1-14. [ Links ]

Márquez, M., N. Ramírez, S. Cortina and S. Ochoa. 2017. Purpose, preferences and fuel value index of trees used for firewood in El Ocote Biosphere Reserve, Chiapas, Mexico. Biomass and Bioenergy 100: 1-9 [ Links ]

Ministerio de Agricultura y Desarrollo Rural (MADR). 2016. Cadenas productivas. Sistema de Información de Gestión y Desempeño de Cadenas. https://sioc.minagricultura.gov.co/Tabaco/Documentos/002%20-%20Cifras%20Sectoriales/Cifras%20Sectoriales%20-%202016%20Octubre.pdf/ (5 de marzo de 2018). [ Links ]

Munanga, W., F. Mugabe, C. Kufazvinei and E. Svotwa. 2014. Evaluation of the curing Efficiency of the rocket barn. International Journal of Agriculture Innovations and Research 3 (2): 436-441. [ Links ]

Olivares J., F. Avilés, B. Albarrán, S. Rojas y O. Castelán. 2011. Identificación, usos y medición de leguminosas arbóreas forrajeras en ranchos ganaderos del sur del estado de México. Tropical and Subtropical Agroecosystems 14: 739 -748. [ Links ]

Pérez, S., C. Renedo, A. Ortiz, M. Mañana, F. Delgado and C. Tejedor. 2011. Energetic density of different forest species of energy crops in Cantabria (Spain). Biomass and Bioenergy 35: 4657-4664. [ Links ]

Pinto, R., F. Medina, H. Gómez, F. Guevara y A. Ley. 2014. Caracterización nutricional y forrajera de Leucaena collinsii a diferentes edades de corte en el trópico seco del sur de México. Revista de la Facultad de Agronomía (LUZ) 31 (1): 78-99. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, M., V. Hoyos y G. Plaza. 2012. Chemical characterization of some soils from four counties that produce Flue-cured tobacco. Agronomía Colombiana 30 (3): 425-435. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis System (SAS) 2013. SAS: Statistical Analysis System. SAS Institute. Cary, NC USA. n/p. [ Links ]

Siddiqui, K. 2001. Analysis of a Malakisi barn used for tobacco curing in East and Southern Africa. Energy Conversion and Management 42 (4): 483-490. [ Links ]

Zhang, C., P. Li, X. Chen, J. Zhao, S. Wanb, Y. Lin and S. Fu. 2016. Effects of Eucalyptus litter and roots on the establishment of native tree species in Eucalyptus plantations in South China. Forest Ecology and Management 375: 76-83. [ Links ]

Received: April 11, 2018; Accepted: December 01, 2018

texto en

texto en