Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.8 no.40 México mar./abr. 2017

Articles

Diversification of the traditional shadow of coffee trees in Veracruz through timber species

1Programa de Posgrado, Colegio de Postgraduados. México. Correo-e: sergio.sanchez@colpos.mx

2 Colegio de Postgraduados, Campus Veracruz. México.

3Campo Experimental Pabellón de Arteaga. CIR Norte Centro. INIFAP. México.

The central region of the state of Veracruz is considered one of the most important producers of shade coffee and the innovation coffee at the state has brought many improvements to the benefit of producers and consumers. Diversification with timber trees is one of them. In order to document the existence and the forms of wood utilization and the economic contributions of tree species introduced in shade coffee farms in the center of the state of Veracruz, semi-structured interviews were conducted in Huatusco and Coatepec, and the main timber species were recognized. Introduced and native or from the region species were found. Of the first kind, there are the pink cedar of India (Acrocarpus fraxinifolius), grevilia (Grevillia robusta), tulip of India (Spathodea campanulata), bracatinga (Mimosa scabrella), piocho (Azadirachta indica), duela (Schizolobium parahyba) and primavera (Tabebuia chrysantha). Native species include ixpepelt (Trema micrantha), texmol (Quercus robur), cacaotillo (Virola guatemalensis), red cedar (Cedrela odorata), mango (Mangifera indica), vainillo (Inga vera), oak (Quercus laurina) and pambacillo (Alchornea latifolia). Producers prefer the wood of red cedar and oak, but in the case of firewood they rather use oak, pink cedar, pambacillo and vainillo. For shade of coffee plantations, growers prefer the latter.

Key words: Shade coffee; coffee cultivation; tropical timber species; diversification; use of wood; Veracruz

La región centro del estado de Veracruz se considera una de las más importantes productoras de café bajo sombra y la innovación en la cafeticultura estatal ha aportado numerosas mejoras en beneficio de los productores y de los consumidores. La diversificación con árboles maderables es una de ellas. Con el fin de documentar la existencia y las formas de utilización de la madera y los aportes económicos de especies arbóreas introducidas en fincas de café de sombra en el centro del estado de Veracruz, se realizaron entrevistas semiestructuradas en Huatusco y Coatepec, y se identificó a las principales especies maderables. Se reconocieron especies introducidas y nativas o de la región; de las primeras, destacan el cedro rosado de la India (Acrocarpus fraxinifolius), grevilia (Grevillia robusta), tulipán de la India (Spathodea campanulata), bracatinga (Mimosa scabrella), piocho (Azadirachta indica), duela (Schizolobium parahyba) y la primavera (Tabebuia chrysantha). De las del segundo tipo, ixpepelt (Trema micrantha), texmol (Quercus robur), cacaotillo (Virola guatemalensis), cedro rojo (Cedrela odorata), mango (Mangifera indica), vainillo (Inga vera), roble (Quercus laurina) y pambacillo (Alchornea latifolia). Los productores prefieren la madera de cedro rojo y de encino, conocido localmente como tezmol, pero para leña, encino, cedro rosado, pambacillo o vainillo, y este último para sombra de cafetales.

Palabras clave: Café a sombra; cafeticultura; especies maderables tropicales; diversificación; uso de la madera; Veracruz

Introduction

Coffee cultivation in Mexico began as a multiple agrosystem, generally associated with native tree species with low management and inputs, as well as with low yields called rusticano (Escamilla, 2015). At present, systems similar to the original ones are aboundant, as the traditional systems. In general they are of small extension, maintain a diverse tree structure; the shrub stratus, in its entirety consists almost exclusively of coffee trees (Escamilla and Diaz, 2002; Escamilla, 2015). The coffee production systems are classified into five types: rustican coffee system, traditional polyculture, commercial polyculture, shaded monoculture and monoculture without shade (Escamilla, 2015).

The central region of Veracruz State is considered one of the most outstanding producers of shade coffee, in which they emphasize traditional, shade and commercial shade systems are particularly important.

Some characteristics of the rustic coffee system are the low or no use of agrochemicals and minimal agricultural work (only some pruning and removal of low canopy shrubs). Most of the native species and native palms (Pérez and Geissert, 2004) are conserved as part of the system, due to the commercial or traditional use and the use of family labor. This type of coffee plantations constitutes an agroforestry system, in which coffee is a non-timber horticultural product (Rice and Ward, 1996; Moguel and Toledo, 1999a; 1999b).

From the tree native taxa to the coffee-growing areas of the center of Veracruz, wood of good quality is obtained for local or regional markets; for example, guanacaxtle, avocado, liquidámbar, cypress, walnut, ash, and white and red oak, whose properties are appreciated for the manufacture of furniture, and medium strength for construction. In recent years, species with a double purpose (shade and wood) have been introduced, some of which are Acrocarpus fraxinifolius Arn., Mimosa scabrella Benth. and Melia azedarach L., which are also of economic interest to producers (Soto et al., 1999; Beer et al., 2003; McDonald, 2003; Rojas et al., 2004; Soto et al., 2006; 2007).

Traditional coffee systems tend to have fewer species in the canopy, which usually fulfill the primary function of providing shade. Trees can be marketed as fuel or wood and, in other cases, to obtain commercial fruits. At present, coffee research is also directed towards varieties tolerant to diseases such as rust (Hemileia vastatrix Berk & Broome), through the development of F1 hybrids in some research centers (Van der Vossen et al., 2015). Agroforestry systems are designed for viability within the socio-economic, political-cultural and geographic- ecological complexity of a region (Álvarez, 2003).

Based on the above, the objectives of this work were to document the existence and the forms of use of wood and the economic contributions of tree species introduced in shade coffee farms in the center of the state of Veracruz.

Materials and Methods

The research was carried out in the coffee plantations of the center of Veracruz. Five estates were selected to perform the fieldwork for being cooperating and having a broad knowledge of the coffee production system. In the region of Huatusco were located four (Finca Kassandra, Finca de Bernardi, Finca Ismael Gómez and Finca Genaro Morales); for the second site, Coatepec, Finca La Herradura was visited) (Table 1).

Semi-structured interviews were applied through a dialogue to the representatives of each of the farms (Gueifus, 2002), complemented with a round of the plots; this allowed to recognize the species, as well as to demonstrate the knowledge of the producer about them and of the traditional and commercial cultivation of coffee. Topics related to the production system, the importance of shade, the identification of trees and their uses were discussed.

From the interviews and from the field trips, the species with timber characteristics recognized by the producers were identified. The use of each was described, and their scientific names were recorded from previous studies in the region (Niembro et al., 2010). The topics addressed were utility, management, importance of the tree in the coffee plantation, origin, sales, timber market, and competition with coffee.

Results and Discussion

Three estates are considered as traditional shade coffee plantations, and two with commercial shade. The latter are Kassandra and La Herradura, which provide additional income for the owners.

The use of different tree taxa within the coffee plantation is a practice that the owners have had for a long time. The reasons related to the inclusion of a tree are diverse; mainly they look for species that are positively coupled with the coffee bush. Trees should provide a light shade and a continuous supply of easily disintegrating litter, which nourishes the coffee grower’s soil; they must be of short and light roots, which do not interfere with the root of the main crop, coffee. Currently, producers are looking for trees that generate additional economic benefits such as timber, fruit, ornamental and nitrogen fixers, among others (Robledo, 2015) (tables 2 and 3).

Data derived from the survey indicate that the sale of cherry coffee generates continuous annual profits, in contrast to that of by-products such as tables, posts, molds and fruits. The interviewees mentioned that they anticipated that the income from the wood would be sporadic, that is, it is possible that few trees are sold a year, to whom it may have the means to extract and industrialize them, since the coffee grower does not contemplate these tasks (tables 3 and 4).

Management of coffee species is an activity in which the producer decides what he sows or eliminates. Its biological, economic and cultural needs lead him to design the coffee plantation with certain trees (Cruz, 2004; Martínez et al., 2004), according to the elements that it has. Thus, the diversity in the coffee plantation depends on the purpose of the owner of the estate; for example, vanilla, of the genus Inga, was promoted by the Instituto Mexicano del Café (Mexican Coffee Institute) (Inmecafé), as it fixes nitrogen. Pink cedar and vanilla are susceptible to attack by defoliating insects, but the damage is not fatal. Interviewees consider that both species are suitable for intercropping in the coffee plantation. It is possible to add that the pink cedar wood has a good market, a reason why the Comisión Nacional Forestal (National Forest Commission of Mexico) (Conafor) promoted it during two years.

The present study evidences a select group of species present in the coffee plantations of the region of Coatepec and Huatusco. The main one is coffee, the others are options that can be planted inside the estate, which at any time can be replaced by new ones or recover others that had been discarded. It is therefore pertinent to mention that the decisions that the owners of the coffee plantations take are in constant dynamism, making some productive systems rather uncertain, such as agroforestry systems with timber, fruit and ornamental species.

Based on this dynamism, it can be accepted what was posed by some of the previous research done by Dzib (2003), Beer et al. (2003), Rojas et al. (2004), Jende and Jürgen (2006). These studies highlight that, among the uses of tree species used as shade on coffee estates, timber can be a good alternative to generate income, when coffee production is not profitable or to have cash flow between harvests. In relation to the age of coffee plantations, there are from two to 25 years, which is part of the strategy that producers have to ensure the coffee harvest every year.

The main uses for the different species (Table 4) were wood for rustic constructions such as boards, posts, beams, firewood for food preparation and to toast the fruit of macadamia nut (Finca Kassandra and La Herradura); the contribution of nitrogen to the soil for coffee plant nutrition with species such as vanilla, pink cedar, bracatinga and grevilia (Figure 1), mainly due to the organic matter that they generate in the soil from the decomposition of leaves. Aguilera (2009) identified 31 species, 28 trees and 3 shrubs, which are used for fuel (firewood), in a study carried out in Coatepec communities.

A) Ixpepetl wood sawing. B) Drying of the table. C) Carrying of the table for rural constructions. D) Wood drying in the shade.

Figure 1 Uses of wood: boards for rustic constructions and firewood.

Table 4 Main uses of trees with timber characteristics, identified by producers in the central region of Veracruz.

FHE = La Herradura Estate; FKA = Kassandra Estate; FBE = de Bernardi Estate; FISM = Ismael Morales Estate; FGE= Genaro Gómez Estate.

Table 4 lists the species with timber characteristics recognized by the producers. There are other coffee regions in which the tree species have also been incorporated; thus, in an agroforestry system in Chiapas, Soto (1999) recorded more than 60 woody species in the tree stratum, which are used as food (49.1 %), firewood (31.8 %), and rural construction (10.4 %), as well as others such as the manufacture of handicrafts, live fences, domestic tools, resins, dyes, condiments, dead fences, ornamental and medicinal uses.

The benefits to the agricultural soil of the coffee tree are known by the action of the Fabaceae family fixing trees, which supply high quantities of organic matter in nitrogen, and, consequently, improve the physical, chemical and biological conditions of the substrate, due to the effects of he decomposition of the leaves they shed (Khalajabadi, 2008; Youkhana and Idol, 2009).

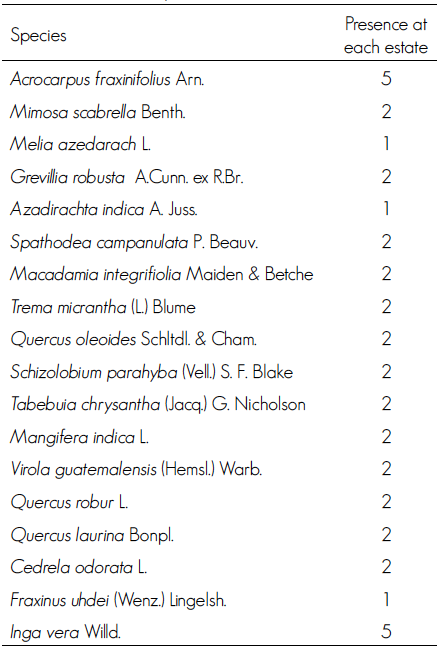

Table 5 shows the distribution of the species in the different estates, among which vanilla and pink cedar stand out as the ones with the greatest presence, since they were recorded in the five studied properties. Other trees such as ixpepetl, macadamia, grevilia and oaks, among others, in at least two of them. This suggests a high importance of the arboreal stratum as a shade of the coffee plantations as well as their usefulness for the agrosystem owners (Robledo, 2015).

According to Escamilla (2015), traditional management systems consist of coffee cultivation along with different species, such as trees, shrubs, grasses, which contribute a further by-product to the owner of the farm. In the case of the specialized coffee system, macadamia is a successful case because it contributes a significant income, related to income from coffee sales. In a study carried out the Atzacan, Ver., Hernández et al. (2012) report that the tendency of coffee producers is to establish ornamental plants instead of coffee because they are more profitable. In the studied region it would be the production of coffee under shade of macadamia, or of timber species the option with better net income.

From the data obtained in the walks and interviews with the coffee owners, several health problems were mentioned, such as the budding of red cedar, which according to the producers, has limited the full development of the species. The attack is widespread, but when it affects the apical bud, its growth is threatened. The cause of this damage is the foliage borer (Hypsiphylla grandella Zeller, 1848) (Pineda, 2014).

Pink cedar is susceptible to infestation by defoliating ants (Atta sp.) and termites (Cryptotermes brevis Walker, 1853) and Nasutitermis corniger (Motshulsky) (Cibrián et al., 1995); vanilla, chalahuite and jinicuil, all three of the genus Inga, are currently being affected by species of the genus Hemiceras, and also by parasitic plants such as Viscum album L. (Arguedas, 2008).

Fungi (Phytoptora sp.) has been found in macadamia trees and they are affecting plantations in productive stage, and some have even been lost because of this fungus that causes yellowing of foliage (ANACAFÉ, 2004). Among the exotic species susceptible to these attacks are the pink cedar of India (FAO, 2007), macadamia and grevilia from Australia (Nath et al., 2011) and bracatinga from Brazil (Mello et al., 2012).

Conclusions

The total number of trees recognized as the most important by the producers was 18 species, both local and introduced. These materials are mainly used for shade of coffee, rustic constructions and firewood. Among the most used in the agroforestry system with coffee are pink cedar, grevilia, duela, vanilla, oak, ixpepetl, macadamia and mango. These species continue to be planted, harvested and replenished within the coffee plantations due to the stability they give to the flow of income in the medium and long term.

In the region of study two farms with commercial production of coffee under macadamia were found. In this combination two products of high value are obtained, relative to the traditional cultivation regime, represented in this study by three other farms. In traditional systems such as those studied here the main income is the sale of cherry coffee, and rarely by trade in fruits or wood. The importance of traditional systems is that they retain a greater richness in the floristic composition of the shade.

Referencias

Aguilera L., C. 2009. Conocimiento sobre la leña de tres comunidades cafetaleras del centro de Veracruz. Universidad Veracruzana. Xalapa, Ver., México. 94 p. [ Links ]

Álvarez O., P. 2003. Introducción a la Agrosilvicultura. Editorial Félix Varela. La Habana, Cuba. 205 p. [ Links ]

Arguedas G., M. 2008. Plagas y enfermedades forestales en Costa Rica. Instituto Tecnológico de Costa Rica. San José, Costa Rica. 69 p. [ Links ]

Asociación Nacional del Café (Anacafé). 2004. Programa de la diversificación de ingresos en la empresa cafetalera. Guatemala, Guatemala. 10 p. [ Links ]

Beer, J., R. Muschler, D. Kass and E. Somarriba. 1998. Shade management in coffee and cacao plantations. Agroforestry Systems 38(1-3):139-164. [ Links ]

Beer, J ., M. Ibrahim, E. Somarriba, A. Barrance and R. Leakey. 2003. Establecimiento y manejo de árboles en sistemas agroforestales. In: Cordero, J. y D. H. Boshier (eds). Árboles de Centroamérica. OFI/ CATIE. Turrialba, Costa Rica. pp. 197-242. [ Links ]

Cibrián T., J., J. T. Méndez M., R. Campos B., Harry O. Tates III y J. E. Flores L. 1995. Insectos forestales de México. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. 453 p. [ Links ]

Cruz, A. 2004. La importancia del hilite blanco Alnus acuminata ssp. arguta (Schlecht.) Furlow, Betulaceae, en la sombra de cafetales de Xochitlán de Vicente Suárez, Puebla. Tesis de Maestría. Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM, México, D. F., México. 194 p. [ Links ]

Dzib C., B. B. 2003. Manejo, almacenamiento de carbono e ingresos de tres especies forestales de sombra en cafetales de tres regiones contrastantes de Costa Rica. Tesis de Maestría. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza. Programa de Enseñanza para el Desarrollo y la Conservación. Escuela de Posgrado. Turrialba, Costa Rica. 124 p. [ Links ]

Escamilla P., E. y C. Díaz. 2002. Sistemas de cultivo de café en México. CRUO- CENIDERCAFE, Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Texcoco, Edo. de Méx., México. 54 p. [ Links ]

Escamilla P., E.2015. Sistemas de cultivo de café en México. Memorias del Curso Anual de Cafeticultura Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Centro Regional Universitario de Oriente. Huatusco, Ver., México. 94 p. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2007. Ecocrop. Acrocarpus fraxinifolius, view crop and data sheet. http://ecocrop.fao.org/ecocrop/srv/en/dataSheet?id=2780 (4 de diciembre de 2007). [ Links ]

Geilfus, F. 2002. 80 herramientas para el desarrollo participativo: diagnóstico, planificación, monitoreo, evaluación. Instituto Interamericano de Cooperación para la Agricultura. San José, Costa Rica. 208 p. [ Links ]

Hernández M., F., A. L. Licona V., E. Pérez P., V. M. Cisneros S. y S. Díaz C. 2012. Diversificación productiva café-plantas ornamentales en La Sidra, Atzacan, Veracruz. Revista de Geografía Agrícola 48-49: 39-50. [ Links ]

Jende, O. y H. A. Jürgen P. 2006. Forestación y reforestación en cafetales. In: Jürgen P., H. A., L. Soto P. y J. Barrera (eds.). El cafetal del futuro. Realidad y visiones. Shaker Verlag. Aachen, Germany. pp. 279-298. [ Links ]

Khalajabadi, S. S. 2008. Fertilidad del suelo y nutrición del café en Colombia. Cenicafé. Chinchiná, Colombia. Boletín Técnico Núm. 32. 44 p. [ Links ]

Martínez, M., V. Evangelista, M. Mendoza, F. Basurto y C. Mapes. 2004. Estudio de la pimienta gorda Pimenta dioica (L.) Merrill, un producto forestal no maderable de la Sierra Norte de Puebla, México. In: Alexiades, M. y P. Shanley (eds.). Productos forestales, medios de subsistencia y conservación. Estudios de caso sobre sistemas de manejo de productos forestales no maderables, América Latina. CIFOR. Bogor Barat, Indonesia. Vol. 3. pp. 23-41. [ Links ]

McDonald, M. A., A. Hofny-Collins, J. R. Healey and T. C. R. Goodland. 2003. Evaluation of trees indigenous to the montane forest of the Blue Mountains, Jamaica for reforestation and agroforestry. Forest Ecology and Management 175(1-3):379-401. [ Links ]

Mello, A. A., L. Nutto, K. S. Weber, C. E. Sanquetta, J. L. Monteiro de Matos and G. Becker. 2012. Individual biomass and carbon equations for Mimosa scabrella Benth. (Bracatinga) in southern Brazil. Silva Fennica 46(3): 333-343. [ Links ]

Moguel, P. and V. M. Toledo. 1999a Biodiversity conservation in traditional coffee systems of Mexico. Conservation Biology 13(1):1-21. [ Links ]

Moguel, P . and V. M. Toledo. 1999b. Biodiversity conservation in traditional coffee systems of Mexico: a review. Conservation Biology 13(1): 1-1. [ Links ]

Nath, C. D., R. Pélissier and C. García. 2011. Promoting native trees in shade coffee plantations of southern India: comparison of growth rates with the exotic Grevillea robusta. Agroforest Systems 83:107-19. [ Links ]

Niembro R., A., M. Vázquez T. y O. Sánchez S. 2010. Árboles de Veracruz. 100 especies para la reforestación estratégica. Comisión del Estado Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave para la conmemoración de la Independencia Nacional y la Revolución, Centro de Investigaciones Tropicales. Xalapa, Ver., México. 256 p. [ Links ]

Pérez P., E. y D. Geissert. 2004. Distribución potencial de palma camedor (Chamaedorea elegans Mart.) en el estado de Veracruz, México. Revista Chapingo Serie Horticultura 10(2): 247-252. [ Links ]

Pineda R, J. M. 2014. Aislamiento e identificación de la feromona sexual de Hypsiphylla grandella Zeller. Tesis de Maestría. Colegio de Postgraduados. Montecillos, Edo. de Méx., México. 49 p. [ Links ]

Rice, R. A. and J. R. Ward. 1996. Coffee, conservation, and commerce in the Western Hemisphere. Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center / Natural Resources Defense Council, Washington, DC., USA. 207 p. [ Links ]

Robledo, E. 2015. La diversificación productiva en cafetales del centro de Veracruz. Centro Regional Universitario de Oriente. UACh. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo. Huatusco, Ver., México. 62 p. [ Links ]

Rojas, F., R. Canessa y J. Ramírez. 2004. Incorporación de árboles y arbustos en los cafetales del valle central de Costa Rica. ICA-FE/ITCR. Cartago, Costa Rica. 151 p. [ Links ]

Soto P., L. 1999. Manejo de especies arbóreas para sistemas agroforestales en la región maya tzotzil-tzeltal del norte de Chiapas. Conabio. México, D. F., México. 25 p. [ Links ]

H. J. de Jong B., E. Esquivel B. y S. Quechulpa. 2006. Potencial ecológico y económico de almacenamiento de carbono en cafetales. In: Jürgen P., H. A., L. Soto P. y J. Barrera (eds.). El cafetal del futuro. Realidad y visiones. Shaker Verlag. Aachen, Germany. pp. 373-380. [ Links ]

Soto P., L., V. Villalvazo L., G. Jiménez F., N. Ramírez M., G. Montoya and F. L. Sinclair. 2007. The role of local knowledge in determining shade composition of multistrata coffee systems in Chiapas, Mexico. Biodiversity and Conservation 16(2):419-436. [ Links ]

Van der Vossen, H., B. Bertrand and A. Charrier. 2015. Next generation variety development for sustainable production of Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica L.): a review. Euphytica 204(2): 243-256. [ Links ]

Youkhana, A. and T. Idol. 2009. Tree pruning mulch increases soil C and N in a shaded coffee agroecosystem in Hawaii. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41: 2527-2534 [ Links ]

Received: July 28, 2016; Accepted: January 25, 2017

texto en

texto en