Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.8 no.39 México ene./feb. 2017

Articles

State and forest landscape dynamics in Cherán Municipality, Sierra Tarasca, Michoacán

1Unidad Académica de Estudios Regionales de la Coordinación de Humanidades de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. México. Correo-e: arredondo@humanidades.unam.mx

The work described here analyzes the state and dynamics of the forest landscape in the Cherán municipality located in the central part of the Meseta Purépecha region of Michoacán State. The spatial configuration and transformation of the landscape is due to both natural and socio-cultural factors; from this perspective, takes a leading role as the synthesizing element of anthropic intervention on the natural physical environment. The description was based on a photographic inventory and the landscape dynamics in georeferenced spatial information in a GIS that is obtained from the interpretation of aerial photographs and Landsat satellite images. The resulting maps were subjected to a statistical analysis to calculate the surfaces, Deforestation Indices (r) and Annual Average Transformation (ITMA) to evaluate the magnitude of the change in the area covered by forest. Results indicate that the current state is subordinated, inter alia, to the geographical situation of the municipalities in the region and the communication channels, while the dynamics, in terms of land use, has been characterized by a long history of deterioration that, in the last three decades, has been reduced by the effects of abandonment with the consequent expansion of the forest area. The results indicate that the state of forest landscape is subject, among other things, to the regional geographical situation of the municipalities, while the landscape dynamics -in terms of the land uses- has been characterized by a long history of deterioration that has been diminished in the past three decades due to the abandonment of the land use, so the forest area has been gradually expanded.

Key words: Cherán; forest dynamics; Meseta Purépecha region; landscape; spatial transformation; land use

El trabajo que se describe a continuación analiza el estado y dinámica del paisaje forestal en el municipio Cherán ubicado en la parte central de la región Meseta Purépecha del estado de Michoacán. La configuración y transformación espacial del paisaje obedecen tanto a factores naturales, como socio-culturales; desde esta perspectiva, el paisaje retoma un papel protagónico al ser el elemento sintetizador de la intervención antrópica sobre el medio físico natural. La descripción realizada se basó en un inventario fotográfico y la dinámica del paisaje en información espacial georreferenciada en un sistema de información geográfica (SIG) que se obtiene a partir de la interpretación de fotografías aéreas e imágenes de satélite Landsat. Los mapas resultantes se sometieron a un análisis estadístico para calcular las superficies, los Índices de Deforestación (r) y de Transformación Media Anual (ITMA) para evaluar la magnitud del cambio en la superficie cubierta por bosque. Los resultados indican que el estado actual está subordinado, entre otros aspectos, a la situación geográfica que guardan los municipios en la región y las vías de comunicación, en tanto que la dinámica, en términos de los usos del suelo, se ha caracterizado por una larga historia de deterioro que, en las últimas tres décadas, se ha reducido por efectos de abandono con la consecuente expansión de la superficie forestal.

Palabras clave: Cherán; dinámica forestal; Meseta Purépecha; paisaje; transformación espacial; uso de suelo

Introduction

In order to explain the impact of the processes of occupation and land use on the environmental and landscape dynamics in mountain areas from a space-time perspective, the scientific research of the last decades has focused on the diagnosis of the present state and trends in Coverage Changes and Land Use (CCUS, for its acronym in Spanish). Its study has been made in regard to human activities involved in several environmental processes of global relevance (Houghton, 1994; Ojima et al., 1994; Riebsame and Parton, 1994; Schweik et al., 1997; Price, 1999; Olsson et al., 2000; Tekle and Hedlund, 2000; Turner et al., 2003), such as deforestation, climate change (Houghton et al., 1999) and soil degradation (Tolba et al., 1992), which have been identified as factors that impact on the structures and functions of the environmental and landscape systems (Kasperson et al., 1995; Everham and Brokaw, 1996; Vitousek et al., 1997), at different scales of analysis: global, regional and local (Cortina et al., 1998).

It has been determined that one of the most serious impacts of land use change is deforestation (Bocco et al., 2001). To this process (the disappearance of forest masses, mainly caused by human activities) is attributed the fact that large tracts of forest on the planet have been reduced by 44 % (Houghton, 1994), with consequent serious damage to the environmental system and mountain landscapes. The problem gets worse when the remaining forests, after the deforestation process, experience varying degrees of fragmentation. As such, it is understood the process of spatial segregation of entities that, when segmented, manifest a decrease of the original habitat, increase of the landscape heterogeneity and greater isolation of the fragments (He et al., 2000; Carsjens and Lier, 2002; Jongman, 2002).

Of the total national territory, 89.60 % of the surface corresponds to rustic lands; from these, 37.60 % are privately owned and 51.4 % are socially owned, and it is distributed among 3 500 000 ejidatarios and comuneros. Also, the vast majority of Mexico’s forest areas and watercourses, mineral resources, flora and fauna are under this ownership regime (Inegi-Semarnat, 2000). Robles and Concheiro (2004) point out that of the more than 29 000 villages and rural communities, 82 % have at least one natural resource that can be exploited. In fact, they add, that 28 % of the forests and half of the forests that exist in the country belong to indigenous peoples.

In Mexico, demographic explosion, agrarian distribution, development and expansion of agricultural activities coupled with the deforestation and livestock program have been identified as the main causes of the transformation of land uses. For example, between 1970 and 1990 there was a 39 % increase in agricultural land, while the area devoted to livestock production rose to 15 % (Inegi-Semarnat, 2000). Due to the above, the loss of wooded area in the country was more than 42.7 million hectares (Semarnap, 1998), of which 82 % were due to deforestation, 2 % to changes in land use, 4 % to forest fires and 8 % to illegal logging, leaving the proportion of forest cover per capita below the world average (Masera, 1996; Velázquez et al., 2001).

Within this framework, Michoacán is one of the states most affected by unplanned land use changes (Masera, 1996; Bocco et al., 1999; Semarnap, 1998). According to these authors, Michoacán lost 513 644 ha of temperate forests in the period between the ‘70s and ‘90s of last century, while the disturbed surface reached 1 355 878 ha (21.51 % of the total forests), only surpassed by the area for agriculture and the grasslands (24.61 %). For example, the area occupied by semi-permanent crops increased 13 times (from 39 784 ha to 508 009 ha), while the forest area decreased by 28.40 % (from 1 811 232 ha to 1 297 188 ha) (Inegi-Semarnat, 2000).

During this period, the annual deforestation rate was 1.8 % and the trends are directed towards the intensification of deforestation, which could lead to a decline of forest area by 55.9 % compared to its situation in the 1970s. Temperate forests are only 23% likely to be conserved, compared to 36 % that might become open forests (Bocco et al., 2001).

In contrast to the evidence that indicates the reduction of the forest area in Michoacán, Cortina et al. (1998) found significant processes of regeneration of the forests attributed to the economic crisis of the early 1980s, the sudden increase in the cost of production, and changes in environmental and forest policies. More than a conservation policy, other authors point out that the recovery of forests is an effect of migration and structural changes in rural development, which led, between 1980 and 2000 (Velázquez et al., 2003) to abandonment of lands in the first case, and the organization of indigenous groups dedicated to the conservation of forests with ecotourism practices, in the second. Reyes et al. (2003) also point out that, although some financing granted between 1993 and 1995 (including the government reforestation program) was intended to improve the conditions in the countryside, they were allocated to family economic sustenance by peasants, which stopped the extraction of wood and favored the conservation of the forest spaces.

One of the most affected areas by unplanned land use changes in the state of Michoacán is the Purépecha region. This region is located in the central and northwestern portion of the state of Michoacán, in a mountainous area (6 000 km2) that extends between 1 600 and 3 200 masl of the Transversal Neovolcanic Axis. The climate is predominantly subhumid temperate; however, the orientation of the slopes and altitudinal slope (1 600 m) that exhibit its mountains of volcanic origin generate three subtypes: temperate humid, semi-warm humid and semi-humid humid, all with abundant rains in summer, with an average annual rainfall between 1 260 and 1 500 mm. Its population is concentrated in 22 municipalities, mainly; however, the indigenous presence in the region (23 % of the total population of the region) is gathered in only 14 municipalities, of which seven are considered indigenous, four with indigenous presence and three with dispersed indigenous populations (CDI, 2006).

Recent studies indicate, for example, that between 1976 and 2000, the Purépecha region lost 17 484 ha of forests converted by land-use change into another type of cover with an annual exchange rate of -0.34, while the crops increased to 11 163 hectares with a positive rate of change equal to 0.29 % (Garibay and Bocco, 2007). These data reflect that the region has been subject in the last decades to intense processes of change of land use that reflect the anthropization of the regional landscape. It is estimated that during the 1976-2000 period the rate of deforestation of the primary forest and the agricultural area converted into avocado crops was 1.8 (7 343 ha) and 3 % (12 268 ha), respectively, and that the permanence of this plantation rose to more than 34 606 ha (8.5 %). Garibay and Bocco (2007) point out that changes in land use in this region as a result of the regional market decline are associated with three main processes: a) regional specialization in forest harvesting, b) the expansion of avocado monoculture and, c) the bankruptcy of the maize-cattle farming system.

The actual study focused on the current state and the dynamics exhibited by the forest landscape in Cherán municipality starting from the assumption that land tenure is the probable cause that explains them, from the law lack of definition in communal lands. This situation acts as a starting agent of the conflicts that occur in such lands and the limits with other indigenous communities or ejidos, internal disputes within the same community, disobediences that induce undercover felling, which favors intense deforestation processes.

Materials and Methods

The study area

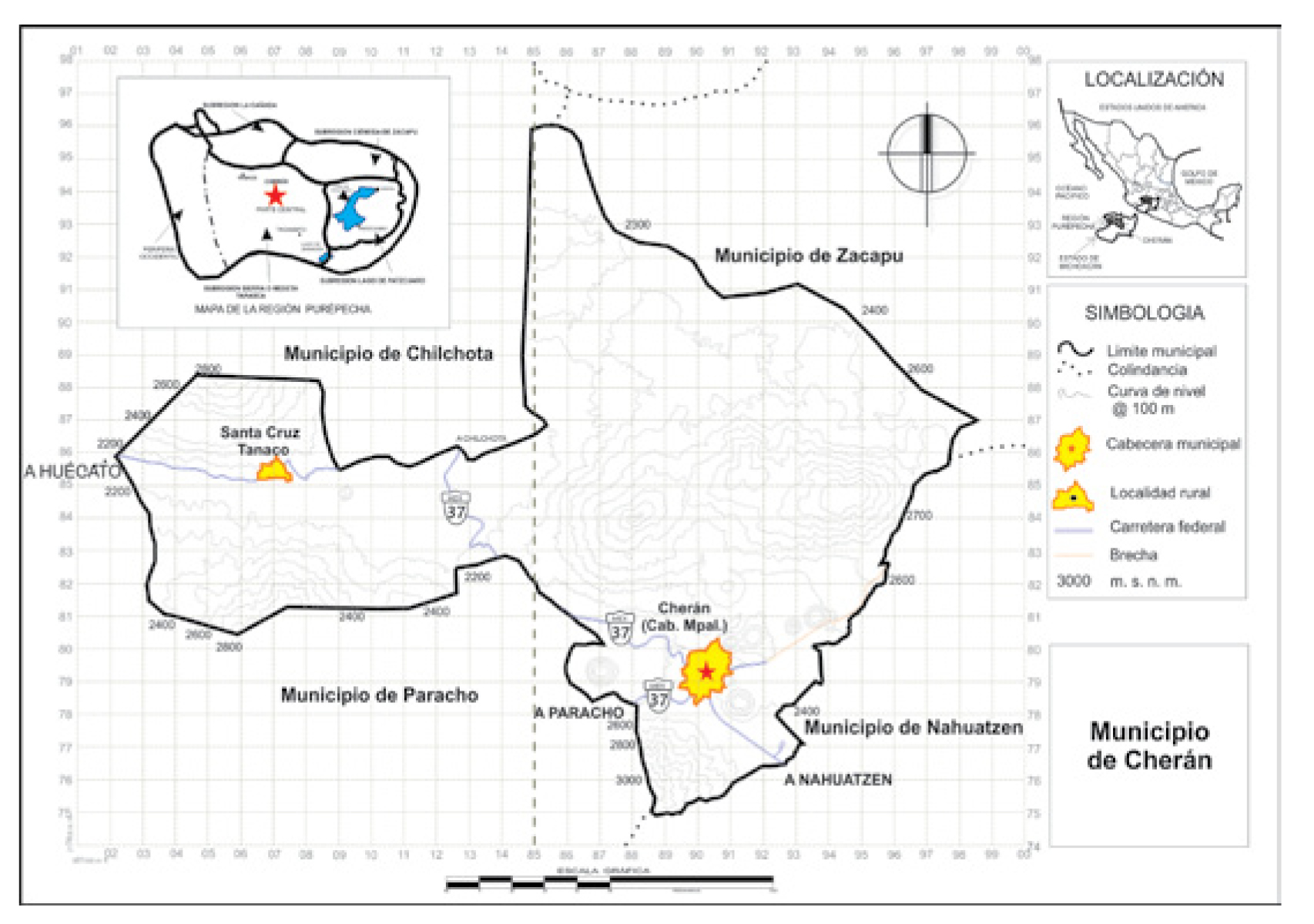

Cherán (221 km2) is one of the 11 municipalities that make up the Purépecha region. It is located in the central part of the region at a height above sea level of 2 400 m, and shares the territorial space with Zacapu, Nahuatzen, Paracho and Chilchota municipalities. Here prevails a temperate climate with rains in summer, with temperatures of 4.1 to 25.4 °C and an annual rainfall near 930 mm, which generates a bioclimatic floor conformed mainly by mixed forests of pine-oak where forest harvesting takes place and to a lesser extent, but not least important, temporary agriculture.

Of the total number of human settlements (17) recorded by Cherán municipality, two represent 96 % of its total population: the municipal head of the same name (12 331 inhabitants) and the community of Tanaco (2 860 inhabitants) (Inegi, 2005) (Figure 1).

A first phase of the present work consisted on describing the state of the landscape from a physical-geographical and anthropic perspective of Cherán municipality with the aim of contextualizing it at the local and regional levels.

The dynamics of the landscape were addressed in three periods: 1976-1986, 1986-2000 and 1976-2000. Thus, land cover maps based on the interpretation of aerial photographs (scale 1: 75 0000) (Inegi, 1995), Landsat MSS satellite images of 1976 and 1986 and Landsat ETM of 2000 were elaborated in SIG (ILWIS ver 3.0). The photographs were converted to digital format at a resolution of 500 DPI and imported into the GIS with a resolution of 2 m per pixel (Campbell, 1996). The satellite images were georeferenced using the Tie-Points method, for which the Digital Terrain Model (DTM) was elaborated from altitude data in Inegi (1995) DXF format, with at least eight control points extracted from the map of land use and vegetation at a scale of 1: 50 000. In order to verify the correct overlap of the images, the RMSE or SIGMA =<2 precision index (ITC, 2001) was used.

A minimum map area of 4 ha (Campbell, 1996) was considered from aerial photographs of 1995, which offer the best resolution (2 m per pixel), and from the resulting map, satellite images are interpreted; first the most recent and best resolution (2000 and 1986) and then the 1976 image, whose interpretation was made on the map of covers of the year 1986. To avoid errors due to the different resolution of the images, the covers are digitized by a method of interpretation of “visual” class (Mas and Ramírez, 1996; Arnold, 1997; Chuvieco, 2002; Slaymaker, 2003), which consists of a series of direct, associative and deductive techniques of interpretation to differentiate “traits” from the covers on the images (Powers and Khon, 1959; Enciso, 1990; Mas and Ramírez, 1996). In order to obtain a better differentiation of the covers, red, green and blue color compounds were used: 2, 3, 4 in Landsat MSS and 3, 2, 1 (natural color) and 4, 5, 7 (false color) in Landsat TM.

To establish the class of the covers of land, the natural / cultural origin, the physiognomic development of vegetation, the class and the intensity of land use, as well as the permanence of the disturbance associated to the use were considered. In order to verify, adapt and, if necessary, correct the cartographic and classification information, the criteria of the 1:50 000 map of land use and vegetation were considered, also carrying out inspections and field interviews.

The resulting maps were subjected to a statistical analysis to evaluate the magnitude of soil cover dynamics. The data obtained in GIS were exported to a statistical package to calculate the surfaces, the Deforestation Indices (r) (Dirzo and García, 1992) and the Annual Average Transformation index (ITMA) (Nascimento, 1995).

Annual Average Transformation index (ITMA) proposed by Nascimento (1995):

Where:

k |

= Annual Average Transformation index (ITMA) |

x 0 |

= Soil cover at the beginning of the period |

x 1 |

= Soil cover at the end of the period |

n |

= Time of the period |

Deforestation Índex (r)

Where:

r |

= Deforestation Índex |

A1 |

= Forest area at the beginning of the period |

A2 |

= Forest area at the end of the period |

t |

= Lapse in years |

From these indexes, transition matrixes were made to measure and classify changes according to the kind of process and four variations: a) positive -conservation and regeneration- and b) negative -intensification and distrub. The first ones include a) conservation or permanence of full-grown forests with disperse forest use, b) regenertion or substitution of one type of cover by other of greater “naturality” and development (the mature vegetation is taken as a reference).

Results

Landscape state

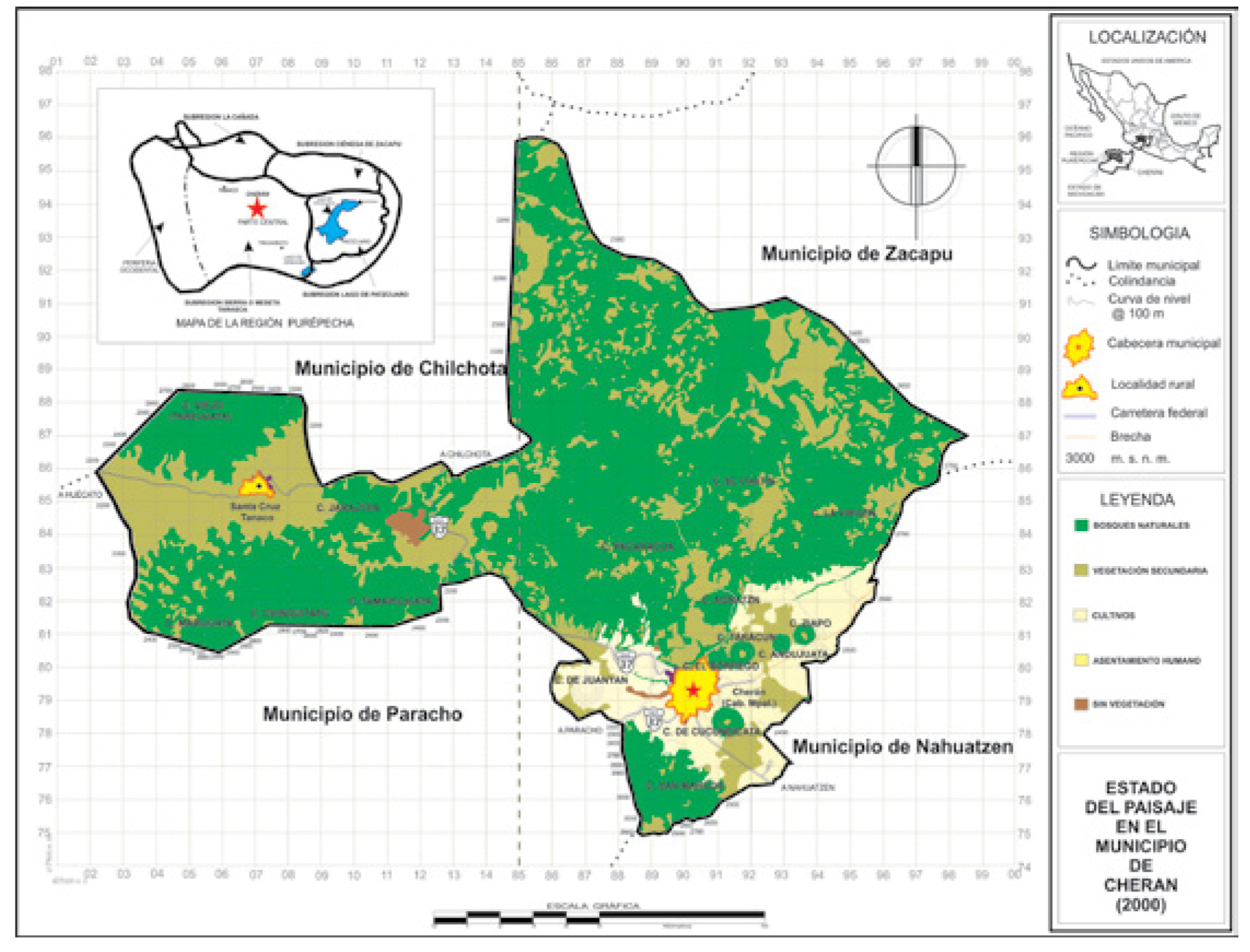

Of the total area of Cherán municipality, 63.68 % corresponds to mixed natural forests of pine-oak (BPQ) among other forest formations, followed by secondary vegetation (MP = 26.05 %) which is made up by shrubland and grassland. Temporary (TC) crops occur in 8.75 % of the territory. This municipality is characterized by a high number of patches of secondary vegetation (MP = 320) that represent 87.91 % of the total fragmentation and 26.05 % of the surface of the municipality. The presence of patches between one and five hectares stands out (168). Forest fragments (BPQ = 33), two large and compact, constitute 9.06 % of the total area and 63.68 % of the surface of the municipality; one measures 9 547.69 ha and another one of 2 488. 88 ha. Human settlements (AH) are gathered mainly by the municipal head (0.85 %) and Santa Cruz Tanaco (0.16 %); and the landscape representation of the soil devoid of vegetation or without apparent vegetation (SDV = 0.48 %) is scarce.

The landscape of the forest system

This type of landscape is composed of temperate coniferous and oak forests, which are composed of pure fir masses (Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. et Cham.) and pine (Pinus spp.), as well as mixed pine-oak (Pinus- Quercus). In the fir forest, as in other parts of the Meseta Purépecha, it can be found in the form of isolated patches on a hill, a slope or a glen. The bioclimatic floor of this plant formation requires rainfall above 1 000 mm and an average annual temperature of 7 to 15 °C.

This plant community presents the three strata: arboreal, shrub and herbaceous; The first of which reaches an average height of 30 m. Cups of the dominant species usually project between 80 and 100 % of the land (Rzedowski, 1988). If the amount of light penetrating into the interior of the forest is sufficient, an understory is formed by a moderately dense shrub, represented by Arctostaphylos arguta (Zucc.) D C., Symboricarpos microphyllus (Humb.& Bonpl. ex Schult.) Kunth, Ribes ciliatum Humb. et Bonpl. ex Roem et Schult., Salix oxylepis C. K. Schneid, Solanum cervantesii Lag, Acaena elongata L. and Salvia spp., among others and a herbaceous stratum composed of Echeveria secunda Booth ex Lindl., Eupatorium glabratum Kunth, Peperomia campylotropa A. W. Hill, Sigesbeckia jorullensis Kunth, Stellaria cuspidata Willd. ex Schltdl. and Senecio spp., among other species.

The opposite happens in the absence of sunlight, since when light is insufficient in the understory of the fir forest, the vegetation becomes scarce. In this case, a soil cover composed of mosses that cover 60 and up to 95 % of the surface develops (Madrigal, 1967).

Although this forest forms pure masses, it is common to find associations with pine (Pinus spp.), oak (Quercus spp.), adler (Alnus acuminata Kunth), strawberry tree (Arbutus spp.), ahuejote (Salix paradoxa Kunth), white cedar (Cupressus lusitanica Mill.) and jaboncillo (Clethra mexicana DC.), among other tree species (Carranza, 2005). This community is located in the most outstanding peaks of Cherán municipality, San Marcos, El Pajarito and Pito Real hills.

There are associations of pine in its pure form or associated with other tree species, one of which is madroño (Arbutus) and oak (Quercus).

Rzedowski (1988) stated that the seasonal structure and behavior of each mixed pine-oak forest depends on the relative proportion of the dominance of either. These forests typical of the subhumid temperate zone are 8 to 12 m high where one or more species of Quercus and Pinus prevail; regularly only the second dominate since this genus demands more light, while the oaks better tolerate the shade and form an arboreal under canopy. One or two arboreal and shrub strata are generally recognized; from it, the Agave, Archibaccharis, Baccharis, Eupatorium, Juniperus, Quercus and Senecio genera stand out. The herbaceous strata are mainly represented by Lamiacea, Rosaceae and Apiaceae.

The pine-oak forest is the most representative type of vegetation in the studied municipality. It is distributed in transition zones in the development of pure oak or pine forests, and in many cases it is the mountainous climax vegetation. They are located in the Pacaracua, El Chatín, La Virgen, Marijuata, Cuinguitapu and San Marcos hills, as well as on the Juanyan and Cucundicata monogenetic volcanoes (Figure 2).

Landscape dynamics

Of the processes that were present between 1976, 1986 (Figure 3) and 2000 (Figure 2), attention is drawn to the conservation that reached 59.32 %. This representation was similar for the periods 1976 to 1986 (63.33 %) and from 1986 to 2000 (61.15 %). In the same way, the intensification of MP and CT as the second one with greater permanence, and the most highlighted in the first period (34.93 %) and of lower intensity between 1986 and 2000 (29.94 %), were exhibited

Regeneration and disturbance showed upward values in all three intervals, as shown by, for example, regeneration - from MP to BPQ, mainly - from 1976 to 1986, from 0.92 % to 4.34 % from 1986 to 2000, and was established at 6.19 % during the whole period (1976 to 2000).

In a period of 30 years at municipal level, BPQ and MP had the most significant permanence, and the most notable change was from MP to BPQ (4.09 %), and vice versa, from BPQ to MP (4.19%). It is also observed the regeneration of MP (1.34 %) by a cessation of agricultural activities, among them, temporary agriculture. Thus, attention is also given to the intervention of the inhabitants of Cherán on secondary vegetation to convert unused land into temporary crops that are potentially suitable for human settlements (AH = 0.62 %). The most dynamic vegetation cover was the secondary vegetation (MP = 4.991 %), followed by pine-oak forests (BPQ = 4.786 %) and temporary crops (CT = 1.67 %).

The Annual Average Transformation Index (ITMA) for the period 1976-2000 highlights AH as the hedge with the highest exchange rate (ITMA = 0.0566) due to the high values reached by ITMA from 1986 to 2000 (0.0867). Although BPQ increased its area between 1976 and 1986 (0.14 km2), this index reveals a loss towards the second period (1986-2000) (0.8623 km2), going from 143.63 to 142.77 km2 with values of ITMA = -0.0004, which confirms its respective negative value between 1976 and 2000 (ITMA = -0.0002). The most important negative index corresponds to TC (ITMA = -0.0162) from 16.49 to 13.13 km2 from 1986 to 2000, which represents a negative ITMA between 1976-2000 (-0.0090), despite the increase obtained in the first period (ITMA = 0.0010). MP does not show significant changes in the first time interval, however, they are moderate in the second, which favored an increase of 2.31 km2, on the one hand, and, on the other, a positive increase (ITMA = 0.0029) (Table 1).

The Deforestation Index (r) indicates that, in 30 years, the soil cover most affected by unplanned land use changes were the forests (r = 0.0002), compared to secondary vegetation (shrubland and grassland) which increased from 56.078 km2 in 1976 to 58.400 km2 in 2000, resulting in negative values in the deforestation index (r = -0.002). Such behavior is due to the disturbance exerted on the forests in the second period where “r” reached higher values (0.0004) in the last 14 years compared to the first one, when the resilience of the forests increased discreetly, which translated into an “ r “almost null (Figure 4).

Discussion

A first approach to understand from a social point of view the state that keeps the rural landscape in the Cherán municipality came from the contact with the main authorities that influence decision making directly or indirectly at regional, municipal and agrarian community level. In relation to the first, the Comisión Forestal de Michoacán (Comof) (Forestry Commission of Michoacán) through its Regional Forestry Delegation, which covers 11 municipalities (Charápan, Tancítaro, Cherán, Taretan, Chilchota, Tingambato, Nahuatzen, Uruapan, Nuevo Parangaricutiro, Ziracuaretiro and Paracho), bring assistance to requesters for conservation and restoration of forest soils; processes the so-called community forestry development programs; authorizes timber harvesting; provides advice for the improvement of forest areas and supports forestry planning, among other efforts.

The communal land conflicts between Cherán and the neighboring communities have transformed the rural landscape of the municipality, especially if they are disputes and disagreements that have to do with the exploitation of the forest resources. The legal uncertainty of these territories (Calderón, 2004) on the one hand, and the recognition of adjacent populations that forests are located on a common property -region-, on the other (Works and Hadley, 2004) were some of the factors that triggered its clandestine exploitation, with intense processes of deforestation in the place.

Although clandestine logging was strongly related to border conflicts between communities, forestry was already part of Cherán since its founding. Nevertheless, the commercialization of the wood in the serranas zones to this municipality was sharpened until the end of the XIXth century with the establishment of sawmills that supplied of wood to the towns of La Piedad, Zamora or Purépero. An important datum provided by Calderón (2004) is the fact that the indiscriminate exploitation of forests increased when the railroad arrived at the end of the Porfiriato; although there is no evidence of a railroad crossing the municipality, there are testimonies that a branch of the railroad might extend from Capacuaro to the territory of Cherán.

This municipality and other surrounding communities provided wood for the elaboration of sleepers, which were subsidized with foreign investment through the so-called leases. A particular case provided by this author and applied to the case of Cherán is the conclusion of a contract, with the approval of the State Government, by means of which the Cherán mountains were leased with all their entrances and exits, use, customs and easements to exploit the forests for a period of 30 years with the possibility of extending to 20 years more.

It should also be noted that public policies in the forest matter rather than favoring the conservation of forest ecosystems have accelerated their deterioration. Merino (2008) points out that public policy failures have been a constant throughout the country’s history, which have had considerable impacts on the forest sector due to the lack of coordination and contradiction between agricultural, forestry and conservation policies. The granting of high subsidies to the agricultural sector, ignorance of the forest character, disarticulation and even contradiction between guidelines and actions are some of the factors that impregnated the rural landscape of Cherán municipality with a wild character.

The internal situation of the farming communities and the training received in forestry are two aspects that explain directly or indirectly the state of the forests and the rural landscape of Cherán. It is estimated that from 2002 to 2007 only one community received training related to the management or care of forest, while the internal situation of these populations was mainly related to conflicts of invasion of land, boundaries and their vicinity.

It can also be pointed out that the condition or state of the forests and the rural landscape of Cherán is exacerbated if conflicts and disputes are added to structural problems and content in terms of their respective community statutes. Like the internal regulations that an ejido enjoys by means of which regulates the use, harvesting, access and conservation of lands of common use, included the rights and obligations of ejidatarios and established with respect to such lands (Article 74 of the Agrarian Law), the agrarian communities have their respective statutes. As such, they regulate and regulate the usufruct of the forest resources of common use in a sustainable way.

The formalization of internal rules in relation to effective control over forests in communal lands strengthens the capacity for decision making in the definition and management of conservation areas. Its omission or lack of compliance is a determining factor that can hinder actions aimed at revitalizing the so-called community forestry development programs, specifically the so-called territorial ordering. In other words, these instruments promote forestry organization and planning.

In the cases of Cherán, Santa Cruz Tanaco and San Francisco Pichátaro, the state of the landscape is understood, as already mentioned, if it is considered from the start, that these are three agrarian communities located in the central part of the Tarascan Sierra, which like the rest of the rural areas of the country, presents conflicting indexes related to the disagreement of land tenure, the dispute over social property and its natural resources (Rascón, 2006). The situation of forest landscapes in these three localities, for example, is strongly linked to the problematic context experienced by these ecosystems on a regional scale: of the 40 agrarian conflicts in the state of Michoacán, 32 are located in the Meseta Purépecha with 18 594 ha in dispute. In this way, the causes that motivate the loss of forests are related to clandestine logging in lands of common use without any authorization from the agricultural communities (Works and Hadley, 2004).

In Cherán, this scenario is exemplified if it is considered that in the last decades this social group collapsed in a strong depression due to the conflicts of boundaries and internal disputes that entailed the transformation of the forest ecosystems in the vicinity with ejidos and agrarian community neighbors. According to information provided by the main local actors, community members and ejido commissars, this conflict was aggravated during the six years of President Carlos Salinas de Gortari, who eliminated the figure of the forest ranger, and from 1994 powers in matters of forest use to federal, state and municipal police were granted, with serious consequences.

Therefore, one of the causes of the state of the forest landscape in the municipality of interest is related to the clandestine networks that have been formed in the last decades, as confirmed by Merino and Segura (2002). This problem is associated with factors such as the problems in the location of boundaries and the delimitation of property rights, the lack of alternatives for the development of villages based on the use of their forest resources, the lack of a legal framework to stimulate a sustainable production in favor of the owners of the resource and the weakness in government institutions to promote sustainable use; a contradiction between guidelines and actions prevails among the same authorities in charge of the management of forest resources, monitor and sanction, Illegal logging.

In addition, access to the forest resource should be considered. Recent studies indicate that the current state of forest landscapes is associated with the geographical location of forest communities in relation to the habitat or human settlement of local actors, as well as the means of communication. Works and Hadley (2004) found in Sevina and Pichátaro, two indigenous communities of the Meseta Purépecha, that the distance that the towns keep in relation to the forests influences the structure and physiognomy of the same. For example, it was estimated that the size and basal area of the Pichátaro forests are related to access to the resource, that is, to greater access to forests, the more intense is the change of land use and the deforestation; whereas the forests that are located in inaccessible lands resultinf from the topographic complexity, show less antropic intervention and thus are kept better preserved.

With regard to the relationship between the state of the forest landscapes and the roads of communication, one is explained by the introduction of the railroad through Tingambato and neighboring municipalities, as well as the federal highway. The deterioration and intensification of land use have always been linked to these two routes of communication, without, of course, discarding the influence of tillage techniques imposed by the Spanish colonization, a new farming system centered on the Egyptian plow, which entailed not only the rupture of the lands of the plain, but also an increase of pastures for cattle and sheep on low slopes of the hills, which led to a decline in the conservation of temperate forests (Garibay and Bocco, 2007).

The railway through Tingambato brought a massive exploitation of the forests. The extracted wood was used for the manufacture of sleepers and poles of light, another amount was transferred to other parts of the country, even exported to the United States of America. The expansion and paving of the road network consolidated a more succulent profitability of the forest by the furniture and building industry in the regional cities of Uruapan, Zamora and Morelia (Garibay and Bocco, 2007). San Francisco Pichátaro is a clear example of it. This agrarian community allocates most of its forest resources to the production of handicraft furniture, among which are bed headboards, beds, bureaus, cabinets, central tables for living rooms and dining rooms, bars, bookshelves, showcases, chairs, as well as wooden sculptures (Works and Hadley, 2004).

All these conditions affect resource availability, disturbance sensitivity and productivity (Arredondo et al., 2008), so that the dynamics of land use in the region has had repercussions on the landscape; However, in the last three decades trends have changed due, among other reasons, to the abandonment of forest use, which has allowed the gradual recovery of this ecosystems (Bocco et al., 2001). According to Farina (1998), this is important because the landscape matrix exerts a significant control over the dynamics of the environmental system, which favors high and medium levels of conservation. Nevertheless, the forestry industry, and in particular the pulp and paper industry, are an important pole of development, based on the use of different pine species for the extraction of timberwood, resin and firewood, the manufacture of coal and for the elaboration of poles, furniture, hard floors and handicrafts in general.

Conclusions

The varied causes of landscape dynamics and associated processes in the Cherán municipality are framed within a pattern that is typical of other municipalities that make up the Meseta Purépecha region. The current state of the forest landscape, associated with negative processes, is rooted in the legal indefinition of communal lands. Uncertainty over land tenure creates conflicts by establishing boundaries and property rights, which in turn generates disputes over social property and its natural resources, which encourages clandestine forest felling on land in common use without the authorization of agrarian communities.

The structural and content problems of the communal statutes in relation to the clear formalization of the internal rules that give certainty to the control of the forest resources explain the state and dynamics of the landscape in terms of the negative processes.

Cherán municipality has been immersed in this condition that undermines the integrity and function of forest ecosystems, and there have been initiatives by Cofom aimed at promoting their conservation and regeneration, as demonstrated by the Proárbol and Procymaf programs, which provide support for reforestation with nursery plants and subsidies to the production of resin, respectively, as well as others aimed at soil conservation and fire prevention and planning instruments leading to municipal land use ordination.

The general pattern of land use in Cherán is similar to that of other areas in the center of the country, the state and other municipalities that make up the Purépecha region: a) predominance of mature forests, although with medium and high values of historical deforestation, which in this case has reduced the forest area in the last decades, (b) decline of fragmented forests, although there has been an expansion of scrub and secondary pastures and (c) regression of temporary crops, although with a certain increase in agroforestry plantations and intensive uses generated from human settlements

Referencias

Arnold, R. H. 1997. Land use and land cover mapping. In: Interpretation of airphotos and remotely sensed imagery. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA. pp. 36-43. [ Links ]

Arredondo L., C., J. Muñoz J. and A. García R. 2008. Recent changes in landscape-dynamics trends in tropical highlands, Central México. Interciencia 33(8): 569-577. [ Links ]

Bocco, G. y M. Mendoza. 1999. Evaluación de los cambios de la cobertura vegetal y uso del suelo en Michoacán (1975-1995). Lineamientos para la ordenación ecológica de su territorio. Proyecto No. 96 06 042, Programa SIMORELOS-CONACYT. Departamento de Ecología de los Recursos Naturales, Instituto de Ecología, UNAM, Campus Morelia. Morelia, Mich., México. 50 p [ Links ]

Bocco, G., M. Mendoza y O. Masera. 2001. La dinámica del cambio del uso del suelo en Michoacán. Una propuesta metodológica para el estudio de los procesos de deforestación. Investigaciones Geográficas 44: 18-38. [ Links ]

Calderón M., M. A. 2004. Historias, procesos políticos y cardenismos: Cherán y Sierra Purhépecha. El Colegio de Michoacán, A.C. Zamora, Mich., México. 335p. [ Links ]

Campbell, J. B. 1996. Introduction to remote sensing. Guilford Press. Guilford, NY, USA. 667p. [ Links ]

Carsjens, G. and V. Lier. 2002. Fragmentation and land-use planning: an introduction. Landscape and Urban Planning 58:79-82. [ Links ]

Carranza, E. 2005. Vegetación. In: Villaseñor G., L. E. (ed.). La biodiversdiad en Michoacán: estudio de estado. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, Secretaría de Urbanismo y Medio Ambiente, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo. Morelia, Mich., México. pp. 38-43. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas (CDI). 2006. Regiones de México. Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo. México. http://www.cdi.gob.mx/regiones/regiones_indigenas_cdi.pdf (20 de mayo de 2016). [ Links ]

Chuvieco, S. E. 2002. Teledetección ambiental. La observación de la tierra desde el espacio. Ariel Ciencia. Barcelona, España. 584p. [ Links ]

Consejo Nacional de Población (Conapo). 2005. Grado de Intensidad Migratoria Medio por municipio. pp. 33-44 33-44 http://www.conapo. gob.mx/work/models/CONAPO/intensidad _ migratoria/pdf/IIM _ Estatal_y_ Municipal.pdf (21 de mayo de 2016). [ Links ]

Cortina, V. S., M. P. Macario y H. Y. Ogneva. 1998. Cambios en el uso del suelo y deforestación en el sur de los estados de Campeche y Quintana Roo, México. Investigaciones Geográficas 38:41-56. [ Links ]

Dirzo, R. and M. Garcia. 1992. Rates of deforestation in Los Tuxtlas, a tropical area in southeast Mexico. Conservation Biology 6: 84-90. [ Links ]

Enciso, J. L. 1990. La fotointerpretación como instrumento de apoyo a la investigación urbana. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. México, D. F., México. 47p. [ Links ]

Everham, E.M. and N. V. L. Brokaw. 1996. Forest damage and recovery from catastrophic wind. Botanical Review. 62: 113-185. [ Links ]

Farina, A. 1998. Principles and methods in landscape ecology. Chapman and Hall, Cambridge, UK. 235p. [ Links ]

Garibay, C. y G. Bocco. 2007. Situación actual en el uso del suelo en comunidades indígenas de la región Purépecha 1976-2005. CIGA Morelia-Delegación estatal de la Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas. Morelia, Mich., México. 66p. [ Links ]

He, Ch., S. Malcolm, K. Dahlberg and B. Fu. 2000. A conceptual framework for integrating hydrological and biological indicators into watershed management. Landscape and Urban Planning 49: 25-34. [ Links ]

Houghton, R. A. 1994. The worldwide extent of land-use change. Bioscience 44(5): 305-313. [ Links ]

Houghton, R. A., J. L. Hackler and K. T. Lawrence. 1999. The US carbon budget: contributions from land-use change. Science 285: 574-578. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática-Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (INEGI-SEMARNAT). 2000. Estadísticas del Medio Ambiente. http://www.paot.org.mx/centro/ inegi/amb1999/amb1999.html (25 de marzo de 2011). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 1995. Fotografía aérea escala 1:75 000. México. http://www.inegi.org. mx/geo/contenidos/topografia/productos _geograficos.aspx (20 de marzo de 2011). [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística Geografía e Informática (INEGI). 2005. II Conteo de Población y Vivienda. México. http://www.inegi.org. mx/est/contenidos/proyectos/ccpv/cpv2005/Default.aspx (17 de febrero de 2010). [ Links ]

Aerospace Survey and Earth Sciences (ITC). 2001. Ilwis 3.0 Academic User’s Guide. ITC. Enschede, Netherland. n/p. [ Links ]

Jongman, R.H.G. 2002. Homogenization and fragmentation of the European landscape: ecological consequences and solutions. Landscape and Urban Planning. 58:211-221. [ Links ]

Kasperson, R. E., J. X. Kasperson, B. L.Turner, K. Dow and W.B. Meyer. 1995. Critical environmental regions: concepts, distinctions and issues. In: Kasperson, J. X., R. E. Kasperson and B. L. Turner. (eds.). Regions at risk: comparisons of threatened environments, United Nations University Press. Tokyo, Japan. pp. 1-41. [ Links ]

Madrigal, X. 1967. Contribución al conocimiento de la ecología de los bosques de oyamel (Abies religiosa) en el Valle de México. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales Boletín Técnico 18. México, D.F., México. 94 p. [ Links ]

Mas, J. F. and I. Ramírez. 1996. Comparison of land use classifications obtained by visual interpretation and digital processing. ITC Journal (3-4): 278-283. [ Links ]

Masera, O. R. 1996. Deforestación y degradación forestal en México. Documentos de trabajo núm. 19. (Enero). GIRA, A. C., Pátzcuaro, Mich. México. 52p. [ Links ]

Merino P., L. 2008. La importancia de los bosques comunitarios. Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales 4(28):8-11. [ Links ]

Merino P., L. y G. Segura. 2002. El manejo de los recursos forestales en México (1992-2002): procesos, tendencias y políticas públicas. In: Leff, E., E. Ezcurra, I. Pisanty y P. Romero L. (comps.). La transición hacia el desarrollo sustentable. Perspectivas de América Latina y el Caribe. Instituto Nacional de Ecología. México, D. F., México. pp. 237-256. [ Links ]

Nascimento, J. R. 1995. Discutendo números do desmatamento. Interciencia 16: 232-239. [ Links ]

Ojima, D. S. 1994. The global impact of land-use change. Bioscience 44(5): 300-304. [ Links ]

Olsson, E., G. Austrheim and S. Grenne. 2000. Landsacpe change patterns in mountains, land use and environmental diversity, Mid-Norway 1960-1993. Landscape Ecology 15: 155-170. [ Links ]

Powers, W. E. and C. F. Khon. 1959. Identification of selected cultural features. Aerial photointerpretation of landforms and rural-cultural features in glaciated and coastal regions, Northwestern University. Evanston, IL, USA. pp. 58-97. [ Links ]

Price, M. 1999. Global change in mountains. Parthenon Publishing. Oxford, UK. pp. 60-61. [ Links ]

Rascón F., F. 2006. Violencia y recursos naturales en México. Informe nacional sobre violencia y salud. Secretaría de Salud y Asistencia. México, D. F., México. pp. 353-374. [ Links ]

Reyes H., H., S. Cortina V., H. Perales R., E. Kauffer M. y J. M. Pat F. 2003. Efecto de los subsidios agropecuarios y apoyos gubernamentales sobre la deforestación durante el periodo 1990-2000 en la región de Calakmul. Campeche, México. Boletín del Instituto de Geografía 51:88-106. [ Links ]

Riebsame, W. E. and W. J. Parton. 1994. Integrated modeling of land use and cover change. Bioscience. 44(5): 350-356. [ Links ]

Robles B., H. y L. Concheiro B. 2004. Entre las Fábulas y la Realidad, los Ejidos y Comunidades con Población Indígena. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana. CDI. México, D.F, México. 128p. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, I. J. 1988. Vegetación de México. Ed. Limusa. México, D.F., México. 432p. [ Links ]

Schweik, C. M., K. Adhikari and P. K Nidhi. 1997. Land-cover change and forest institutions: a comparison of two sub-basins in the southern Siwalik hills of Nepal. Mountain Research and Development 17: 99-116. [ Links ]

Secretaria de Medio Ambiente, Recursos Naturales y Pesca (Semarnap). 1998. Diagnóstico de la deforestación en México. Dirección General Forestal. Unidad del Inventario Nacional de Recursos Naturales. http://www.ccmss.org.mx/descargas/diagnostico _ de _ la _ deforestacion _ en _ mexico.pdf (28 de noviembre de 2007). [ Links ]

Slaymaker, D. 2003. Using georeferenced large-scale aerial videography as a surrogate for ground validation data. In: Wulder M. A. and S. E. Franklin (eds.). Remote sensing for forest environments: concepts and case studies. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Norwell, MA USA. pp. 469-488. [ Links ]

Tekle, K. and L. Hedlund, 2000. Land cover changes between 1958 and 1986 in Kalu District, Southern Wello, Ethiopia. Mountain Research and Development 20: 42-51. [ Links ]

Tolba, M. K., O. A. EL-Kholy, E. El-Hinnawi, M. W. Holdgate, D. F. McMichael and R. E. Munn. 1992. The World Environment 1972-1992. Chapman & Hall. London, UK. 884p. [ Links ]

Turner, M.G., S. M. Pearson, P. Bolstad and D. N. Wear. 2003. Effects of land-cover change on spatial pattern of forest communities in the Southern Appalachian Mountains (USA). Landscape Ecology. 18:449-464. [ Links ]

Velázquez, A., G. Bocco and A. Torres. 2001. Turning scientific approaches into practical conservation actions: the case of Comunidad Indígena de Nuevo San Juan Parangaricutiro, México. Environmental Management 3: 21-32. [ Links ]

Velázquez, A ., E. Durán, I. Ramírez, J. F. Mas, G. Bocco, G. Ramírez, J. L. Palacio. 2003. Land use-cover process in highly biodiverse areas: the case of Oaxaca, Mexico. Global Environmental Change 13: 175-184. [ Links ]

Vitousek, P. M., H. A. Mooney, J. Lubchenco and J. M. Melillo. 1997. Human domination of hearth´s ecosystems. Science 277 (5325): 494-499. [ Links ]

Works, M. A. and K. Hadley. 2004. The cultural context of forest degradation in adjacent Purépechan communities, Michoacán, Mexico. The Geographical Journal 170(1):22-38 [ Links ]

Received: July 28, 2016; Accepted: December 22, 2016

texto en

texto en