Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.7 no.38 México Nov./Dez. 2016

Articles

Protected natural areas and common use system of forest resources in Nevado de Toluca

1Instituto de Ciencias Agropecuarias y Rurales (ICAR). Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. México.

2División de Tecnología Forestal. Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Valle de Bravo. México.

San Francisco Oxtotilpan ejido is an agrarian entity whose territory overlaps with three natural protected areas (NPAs), two of which are under federal governance, while the other one is managed at the state level. About 98 % of the 2107 ha ejido lands are forested. A system of common natural resources management of the area is confronted with conservation policies of the natural heritage, in the form of federal and state protected areas. This situation is expected to reorganize with the current Federal Government proposal of new conservation and management programs for the two protected areas, which would encourage a higher surveillance and legal certainty for natural resources management which would allow the ejido members a broader sense of ownership of their territory. In other terms, the agreements within the ejido, and between the ejido and other community and formal institutions, will be modified so that they will involve pressures to the systems that will necessarily promote their re-organization. This paper brings elements towards the comprehension of this dynamic and for the development of conservation and forest use public policies and actions that consider the social impact on formal and informal community institutions for a participatory management in natural protected areas.

Key words: Protected natural areas; Nevado de Toluca Flora and Fauna Protection Area; Natural Resource Protection Areas of Valle de Bravo-Malacatepec-Tilostoc and Temascaltepec; forest management; Matlatzinca; San Francisco Oxtotilpan

El ejido San Francisco Oxtotilpan posee un territorio de 2 107 ha, de las cuales 98% son forestales y forma parte de tres áreas naturales protegidas, dos federales y una estatal. Esto genera una dinámica que entrelaza el aprovechamiento de recursos forestales a través de la conformación y funcionamiento de un sistema de recursos de uso común del ejido, con la política de conservación del patrimonio natural mediante áreas naturales protegidas. Situación que se reordenará con la propuesta actual del Gobierno Federal de generación de nuevos programas de conservación y manejo para las dos áreas protegidas federales, lo que propiciará más vigilancia y certidumbre normativa para el manejo de los recursos forestales al permitir que los ejidatarios perciban una mayor apropiación de su territorio. Sin embargo, no necesariamente se traducirá en una mejor integración a la cadena productiva. Los arreglos y acuerdos al interior del ejido, y de este con otras instituciones comunitarias y con instituciones formales, se verán modificados, por lo que ejercerán presiones sobre los sistemas naturales, lo que promoverá su reordenamiento. El presente análisis aporta elementos para la comprensión de tal dinámica y para la generación de acciones y políticas públicas de conservación y fomento del aprovechamiento forestal que tomen en cuenta su impacto sobre las instituciones comunitarias formales y no formales afines a un manejo participativo en las áreas naturales protegidas.

Palabras clave: Áreas naturales protegidas; Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Nevado de Toluca; Área de Protección de Recursos Naturales Valle de Bravo-Malacatepec-Tilostoc y Temascaltepec; manejo forestal; Matlatzinca; San Francisco Oxtotilpan

Introduction

One of the most important instruments of Mexican environmental policy is the protected natural areas (ANPs). Even though from the outset it was considered substantial to include the local inhabitants in their management, a conservation vision based on the establishment of permanent closures to the use of forest resources and the expropriation of the territory to be protected was also being carried out (Bautista-Calderón, 2007), which led to the creation of national parks, and with it, a formal restriction on the use of forests for the communities.

In fact, the inhabitants of these areas and their areas of influence make use of the goods and services that these ecosystems provide, and establish community institutions (not necessarily formal, explicit, or recognized by State institutions) that can be framed within the common use of resource systems (Thomé, 2016). One of its main characteristics is the law shared among the members of the community based on a set of access rules accepted by the group and that excludes other agents who do not own or possess the land, although they do not always obey the principle of equality as to the right to use the resource, as rather there are practices of social differentiation (Ostrom, 1990, Álvarez, 2006).

This study took as a case study the San Francisco Oxtotilpan (SFO) ejido, as the formal institution of land management more linked to its community-inhabitants as a system of resources of common use, particularly forestry, since it is recognized, in addition, its close relationship with the protected natural areas in which it is located.

The present work is a contribution to the knowledge of the society-nature relationship in the protected natural areas of Mexico with a qualitative approach that considers the analysis perspective of an indigenous community, Matlatzinca, in the context of the restructuring of the normative framework of the Nevado de Toluca region. The moment of legal adaptation is under discussion by different social actors and, often, without sufficient information on the socio-environmental dynamics of these areas. Therefore, this study can generate some indicators to contribute to the process of designing, implementing and application of new public policies aimed at sustainable use and conservation of environmental goods and services.

Materials and Methods

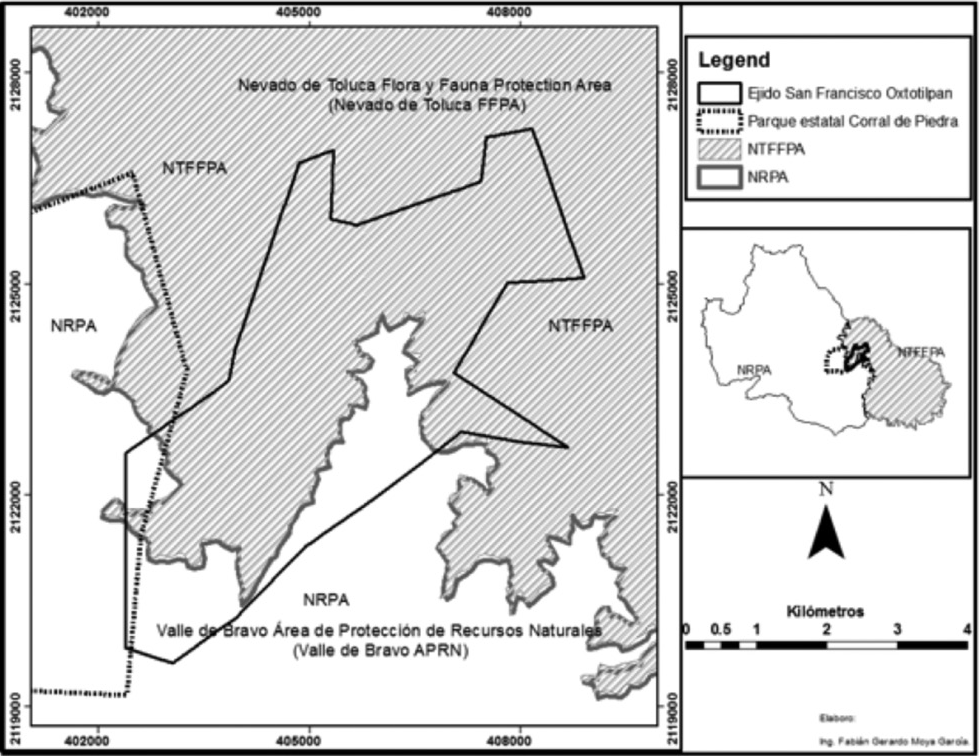

The SFO ejido is part of Temascaltepec municipality, southwest of the State of Mexico, with a total area of 2 107 ha, made up by 1 950 ha of forest (mainly pine and fir), 130 ha of grassland and 27 ha of cultivation and integrated to the Matlatzinca indigenous town (Figure 1). Its soil is of forest vocation, although in it agricultural activities are carried out and to a lesser extent, extensive cattle ranching.

The Matlatzinca territory can be considered as a metasystem, formed by the ejido and the communal goods. Physiographically, the former encompasses, essentially, Pinus and Abies-Pinus forests with small agricultural areas and pastures, while the second includes Pinus and Abies-Pinus forests, agricultural valleys and human settlements that make up the town with its seven neighborhoods. There are no human settlements here, because both, the ejidatarios and the other inhabitants of the village, live in the communal goods.

According to the approach of socioecological systems (Walker et al., 2002), from the 3 000 masl, the protected natural area of Nevado de Toluca, until 2013 with National Park category, contained forest areas that were closed to productive use. Another subsystem was below the mentioned limit, but within the Área de Protección de Recursos Naturales Valle de Bravo, Malacatepec, Tilostoc y Temascaltepec (Natural Resources Protection Area Valle de Bravo, Malacatepec, Tilostoc and Temascaltepec) (APRNVBMTT), with forest utilization zones. Finally, to the west of the ejido is located a small strip in the Santuario del Agua Corral de Piedra (Corral de Piedra Water Sanctuary) State Protected Area.

This scenario has been reclassified from National Park to Protected Area of Flora and Fauna, and until 2016 is undergoing sub-zoning with the elaboration of Conservation and Management Programs of the two federal protected natural areas (Figure 2).

Source: Conanp, 2014; Semarnat, 2016.

Figure 2 Protected Natural Areas and San Francisco Oxtotilpan ejido.

A documentary research was carried out on the use of natural resources and the organization in the agrarian nucleus and the locality, in order to know the background and current situation on the process of appropriation of the territory and its forest resources.

Qualitative methods were used for the collection of first-hand information and a descriptive method for analyzing the perspectives of the ejidatarios.

In the first instance, interviews were carried out with key informants such as agrarian representatives, ejidatarios and family members, advisors to private organizations and public policy operators in the region. During field work, supported by the participant observation method (Kawulich, 2006), the processes of management of government programs were recorded and accompaniment was offered in the supervision of government subsidy programs in forest in local forests.

In the second instance, a survey was conducted on 33 of the 69 ejidatarios in active employment on the perception of the use of the ejido’s forest resources and the relationship with the protected natural area of Nevado de Toluca, through a questionnaire with 18 reagents, with two matrices of double entry on the use of forest resources. It was not considered a probabilistic sample, but a consenting effort on the part of the ejidatarios that was accessed during field work and that in a first application, with only 13 individuals, results showed little variability in the responses. This information was systematized based on a scale of perception of the state of conservation of forest resources, which was ordered and analyzed through descriptive statistics to generate a conceptual model of appropriation of nature through an analysis of the flows (García, 2006; García and Toledo, 2008) applied to the system of common use of forest resources of the ejido.

On the other hand, a scenario was proposed of the use of forest resources in the ejido under the new normative framework considering its current use, obtained through the documentary and field research, comparing it with that allowed in the proposals of conservation and management programs that are being reviewed by federal Nevado de Toluca and APRNVBMTT ANPs.

Results and Discussion

Description of the Common Use Forest Resources System of the San Francisco Oxtotilpan Ejido (SRFUC-SFO).

The SRFUC-SFO is conceptualized as a geographic space delimited within the ejido territory, with 2 080 ha of forest and grassland, with the exception of 27 ha of agriculture. From the social perspective, the 69 ejidatarios are considered directly or indirectly participating in the assemblies and activities agreed by them, of which 48 are men and 21 women.

As an immediate environment of this system, the Communal Goods of SFO and some small properties that together form the SFO town (metasystem) are conceptualized, with important exchanges of matter, energy and information, and even their belongings.

In the sample of surveyed people, the age range is 32 to 85 years, with an average of 67 years for women and 60.7 for men, which represents an aging process in the ejido assembly, although 22% of The ejidatarios are between 30 and 49 years old that would be constituted as their generational change.

The schooling includes a range that goes from the total lack of studies to the finished secondary school (9 years); two dominant groups, one of women without education and the other of men with completed primary education, stand out. The average academic instruction by gender is 1.9 years for women and 4.8 years for men. Based on the above, the fact is that women accumulate more age and less schooling as a result of a historical gender inequality in terms of access to land and education.

It is important to mention that families form networks that give their members a social capital that allows them access to different spaces and availability of resources, promotes greater cohesion among groups, thus forming ways of life that take advantage of the multiple use of the forest. This situation gives the characteristic of diffuse system to the SRFUC, since the comuneros (communers), neighbors and relatives of the ejidatarios can approach to forest resources by their relation with them.

In the case of timber resources (housing, accessory areas and tools), the protected natural area of Nevado de Toluca is the supply area for all members of the town (pueblo) (ejidatarios, comuneros, neighbors and their relatives), whose houses are mainly settled within the lands of the Communal Goods. The president of the Ejidal Commissariat grants the authorization of use for a volume suitable for this use, so that there is no excessive extraction of wood.

With the assistance of a Forest Technical Services Provider (PSTF), the Forest Management Plan is implemented in the area outside the Nevado de Toluca ANP; thus, the volume of wood to be extracted is established, for which the trees are selected and marked for harvesting. In this activity, along with the commercial use of non-timber resources and the payment for hydrological services, those who are entitled to receive profits or distribution, are the 69 ejidatarios formally recognized and listed. In addition, the ejido provides resources for common benefit such as patronage festivals and primary and secondary schools.

For more than 15 years, timber has been sold annually to a buyer in the metropolitan area of Toluca city, who is an entrepreneur of the timber industry, who purchases it on the ground (standing sale) and extracts it with his staff; he also hires a documenter who supervises the extraction of wood and the Supervisory Board supervises these tasks. However, members of the ejido have no knowledge of wood cubication so they are subject to what the technician and the documenter indicate. Finally, the wood in logs, which is now property of the buyer, is transferred to the sawmill for its transformation into commercial products.

The PSTF provides information to the ejido assembly where he is consulted on aspects of forest management and its commercialization, but these explanations are given in a synthesized form and not all are understood by the ejidatarios, nor the agrarian representatives, given their technical complexity and the low levels of education of most of them, who, in many cases, intuit that what they communicate, both the technician and in some cases the buyer of the wood (contractor), is not totally true (the result of interviews with several ejidatarios).

In the natural protected area, since it is not of commercial interest, the technical and scientific knowledge and the monitoring of the territory by the ejido is almost null, except for areas under supervision for having led to the sanitation of the forest, or that are committed for reforestation in government projects and those committed in the Program for Payment for Hydrological Environmental Services. In some occasions they make reconnaissance tours of the place.

In general, there is an ambiguity about the control and appropriation of these lands, for although the ejidatarios know that it is formally of the ejido, they do not consider it under their control, reason why the expression: “To take care, yes it is ours, we have the responsibility, but if we want to take use it, there we can not, it’s not ours, it’s of the government.“ is a very common expression among them.

From the above, it is clear that the technical and scientific data, mensurising and environmental, used to elaborate the Program of Forest Management with which decisions are made in the use of this part of the territory, are manipulated, mainly, by technical agents external to the ejido (PSTF, governmental authorities and buyer, among others). Therefore, a technocratic practice prevails which is more convenient for government representatives than for the community itself, where ejidatarios have limited participation in the control of their forest resources.

From the governmental point of view, it is less complicated to establish a management plan that only considers technical aspects, which could exclude any level of symbolic participation (to inform, consult and appease) and of citizen power (to associate and delegate power) (Arnstein, 1996).

However, in the daily life of the population, labors are carried out in the ejido for the maintenance and conservation of the forest through jobs or cooperative work, as well as extraction roads, under the indications of those who represent the PSTF and the approval of the activities in assembly. In fact, it is not uncommon for the PSTF to be the only indications, and it is the ejidal Commissariat and the Supervisory Board who plan, convene and supervise the tasks in the field.

For example, some community practices such as the use and management of moss (Thuidium sp.), the pearl stick (Symphoricarpos microphyllus HBK.) and the white wand (Salvia hirsuta Jacq.) are highlighted. Buyers outside the SFO approach the authorities to negotiate their exploitation and commercialization. Once the agreement is reached, the agrarian representatives of the ejido request the PSTF to prepare the technical justification study and a notification to Semarnat (Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources). The management for authorization is done between the PSTF and the curator and subsequently such management is “sold” to the buyer, who usually brings his workers to the extraction. Even if such an operation should be to comply with environmental and forestry regulations, it is not supervised by the Supervisory Committee because the same members and workers do not know the regulatory constraints for the sustainable use of the resource.

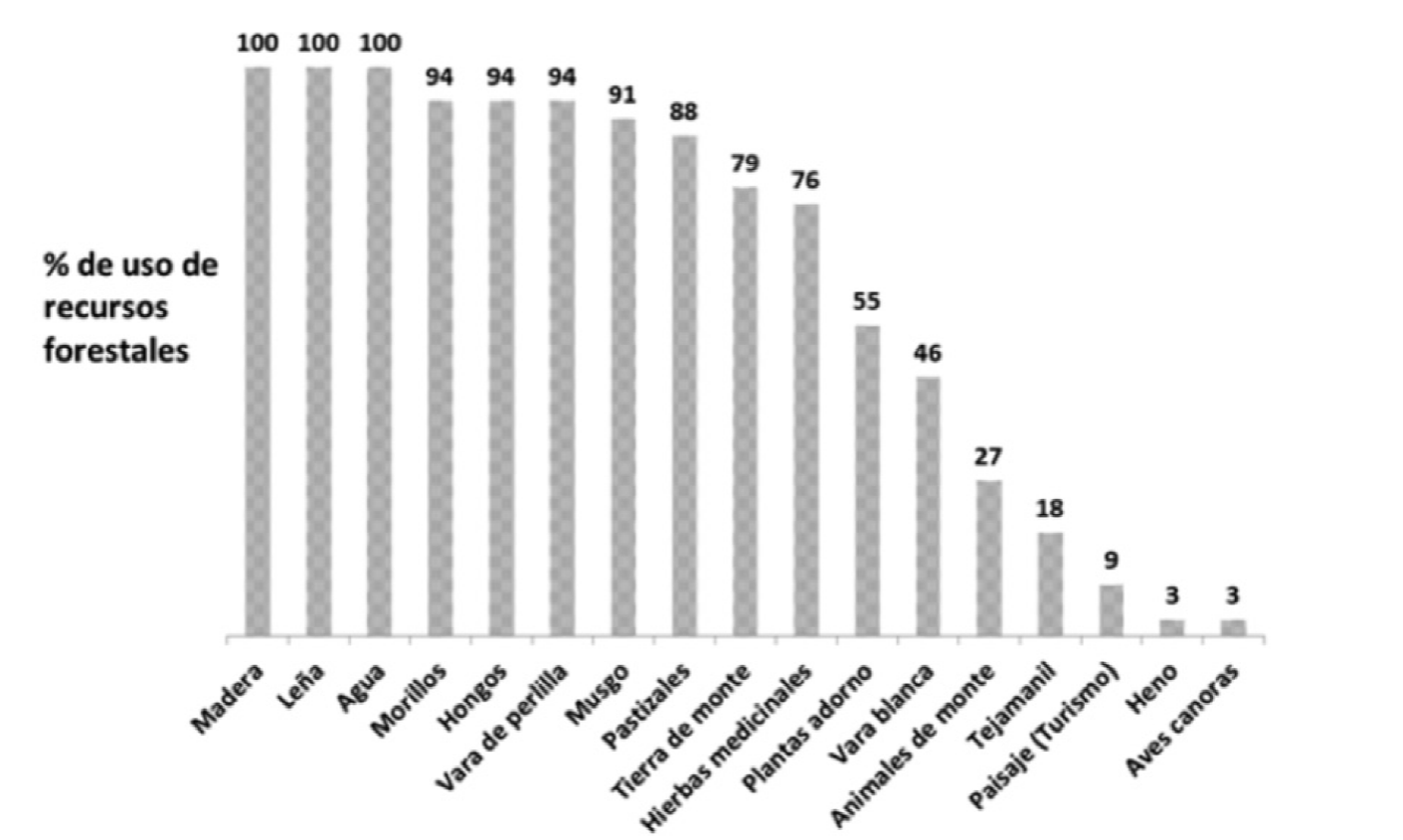

Through the survey on the perception of access to and use of forest products, 17 were identified, of which 11 are recognized by more than half the respondents. The most used resources are wood, firewood, water, morillo, fungi, pearl stick and moss. Access to these is 90% of those identified as ejidatarios and neighbors (Figure 3).

In regard to water, there are 23 springs in the land, 9.2 km of permanent streams and 27.9 km of intermittent flows (Field Information of the San Francisco Oxtotilpan Community Territorial Ordinance), which serve to supply drinking water, and for agricultural irrigation as well as for the cultivation of trout.

Again, based on the results of the survey, it came that the perception on the state of the forest goods is very good and good for most of the ejidatarios in 14 of the 15 mentioned resources, except for the landscape (tourist use), to which it has poor, regular and, to a lesser extent, very poor perception. Figure 4 shows a SFO SRFUC model based on the analysis of flows and appropriation of nature (García, 2006; García and Toledo, 2008).

This system of resources is organized organically with different formal and non-formal institutions that operate in the territory of the SFO town: the two agrarian nuclei, the Municipal Delegates as political authorities linked to the municipality of Temascaltepec, and the Water Committee, which is a non-formal institution validated by the “uses and customs” of theMatlatzinca people.

Uses and customs are protected by the Political Constitution of the Mexican United States (Articles 2 and 33) and linked to the Treaty 169 of the International Labor Organization, ratified by the Mexican Government in 1990 (Gamboa and Gutiérrez, 2008). Thus, the use for self-consumption of several non-timber resources that do not have a specific regulation within national or state legislation falls within this protection or even, in some cases like water and species at risk, the authority does not apply the normative formal systems in the face of the risk of violating the traditions of the Matlatzinca people; therefore, in fact, their management is under the administration of the community institutions.

Formally, forest resources are directly regulated by three federal laws and four regulations, 16 federal environmental standards, two federal and state ANP decrees, three ecological, one state and two regional, and two of conservation and ANP management programs. To consider them all, and once the above-mentioned programs are authorized for both federal ANPs, a rather complex scheme of normative instruments would be obtained to operate efficiently in the SRFUC-SFO, as shown in Figure 5.

Use of territory and income

In 2013, 1 467 ha (64%) of the forest area of 1950 ha had no authorized use and 380 ha (17%) were outside the national park. Likewise, 333.8 ha (15%) received a Federal Government subsidy as payment for environmental services (Conafor, 2013) and 103 ha (5%) received payment for hydrological services from the Government of the State of Mexico (Gaceta de Gobierno, 2013). This changed in 2014, as support ended and only 103 ha (5%) receive the state payment (Gaceta de Gobierno, 2013).

The Forest Management Program is based on the Mexican Method of Irregular Forest Management, which is a selective cutting for the maintenance of an irregular and multispecific forest mass, which seeks to keep the structure of a natural temperate forest. In this program, 16 timber species, 12 broadleaf and 4 coniferous have been identified, which, being the most attractive from a commercial perspective, are focal to forest management. The proposed cutting cycle for timber harvesting is 10 years, which began in 2008 and is scheduled to be completed by 2018.

For 2011, prices for the sale of timber forest products in the region’s market per cubic meter were: $ 1 200.00 Mexican pesos for pine; $ 500.00 Mexican pesos for broadleaves and oak; both amounts are calculated by using 70% roundwood. In 2014, the state government granted a subsidy of a total of $ 154 500.00 Mexican pesos for to pay for hydrological services. Thus, it can be estimated that 20% of the territory under persistent forest use generated 91% of the income.

On the other hand, the subsidies for payment of environmental services for conservation in 5% of the territory contributed with 9% of the income from the forest, while 75% remained as a protected natural area without commercial use of forest resources. It should be noted that not all gross income is distributed as “distribution” to ejidatarios, since a percentage is used to finance administrative and legal actions, social works and operating expenses of the maintenance of the forest (food, materials, equipment, gasoline and vehicle repair).

Evaluation of the ejido level as a Common Use Resources System and as a Community Forestry Company

Based on Álvarez’s (2006) classification on the typology of resources commonly used in Mexico, it is identified that the ejido would be closer to Type 3, although it would have Type 4 elements. In this way the following characterization is obtained:

Type 3. Assisted common resource organizations, because they have a relative control over the access and management of their natural resources. They are usually communities that have achieved the reappropriation of their natural resources and almost all of them have been involved in a struggle for the recovery of control of their resources.

Type 4. Semi-assisted resource-based organizations, because they clearly control access to their natural resources and have community rules and regulations to achieve an equitable distribution of benefits. In general, they are associated with some external or governmental financing whose fundamental purpose is to create governance in the management of common resources.

With regard to ejido participation in the production chain, the level of vertical integration in timber forest production is identified according to the classification of the Semarnat Forest Conservation and Sustainable Management Project (Procymaf) at level II (“ low “), of the four types proposed. It is characterized as follows:

Type II. Producers selling standing timber: owners and / or owners of properties subject to forest exploitation, by third parties through a purchase contract, without the owner or holder participating in any phase of the harvest.

Likewise, based on the Index of Development of Community Forestry Activity (Merino, 2014), the ejido obtains a value of “nine” equivalent to “low level of development of forestry activity”, which is 7.8% of the forest communities of Mexico (Merino, 2014). In socioeconomic terms, this means that the wealth generated by forests is transmitted to subjects outside the ejido.

The perspective with the rearrangement of the ANPs in the western part of the State of Mexico

During the year 2013, in the two federal ANPs that have an impact on the territory of the ejido, Semarnat in collaboration with different actors, made the proposal of Conservation and Management Plans for them. These exercises are performed independently by each of the protected area directions, even though the ejido will have to assume the regulation of both.

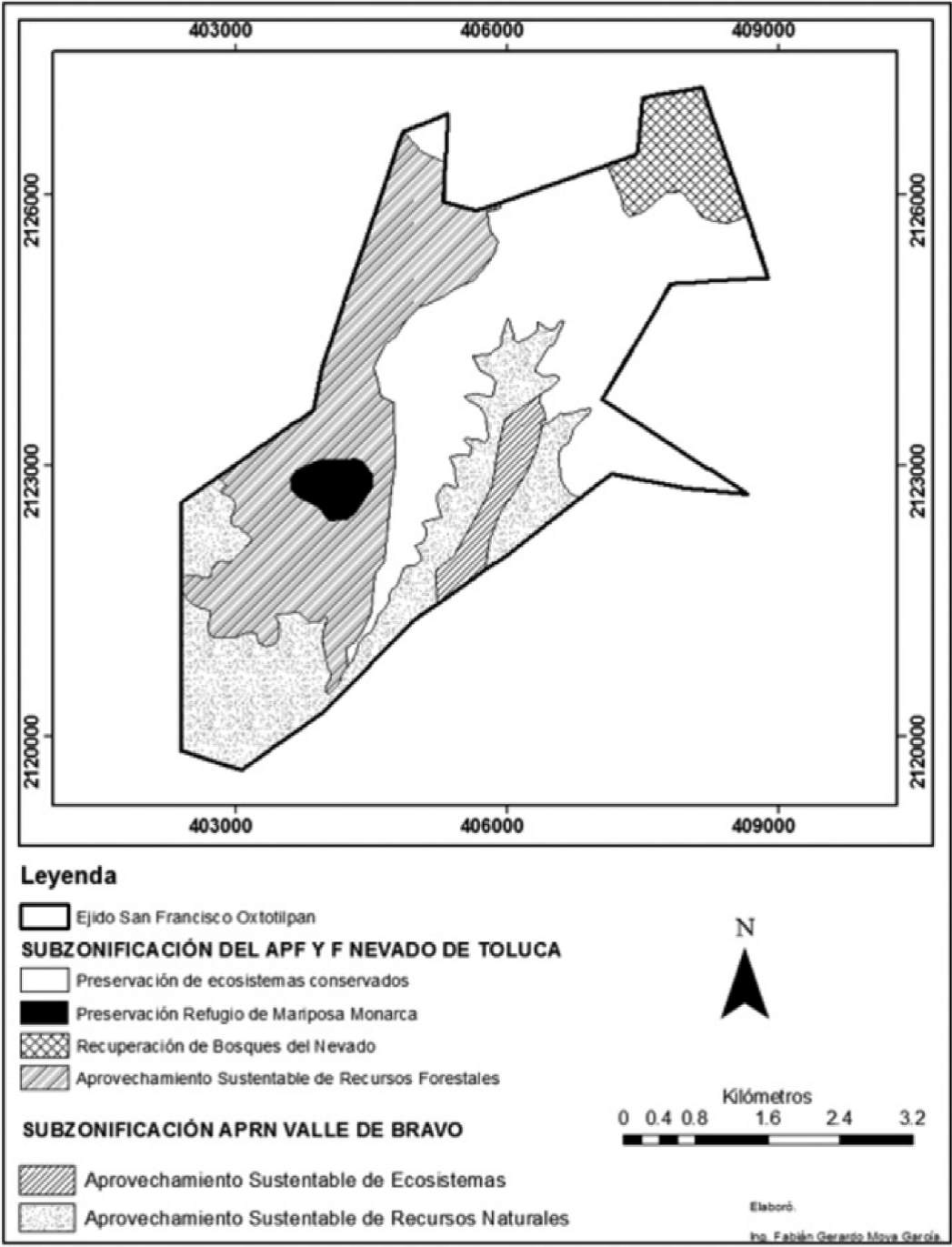

In order to identify the proposed subzoning that will regulate the land use patterns in the ejido, a map was elaborated in which both zonifications proposed in the Conservation and Management Program of each area were combined (Figure 6).

Source: Conanp, 2014; Semarnat, 2016.

Figure 6 Zoning of federal protected natural areas in the San Francisco Oxtotilpan ejido.

Based on the map above, the subzones and activities allowed with direct relation to the SRFUC were identified:

Preservation Sub-areas of Conserved Ecosystems (SPEC)

These subareas appear in the APFF Conservation and Management Program; they include dense Sacred fir forests (Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. et Cham.), in good state of conservation, in canyons with slopes average greater than 40%, the reason why they can be considered fragile ecosystems, because the removal of the vegetation can lead to erosion and loss of the soil. In these places, productive activities of low environmental impact would be permitted, as well as forest management for the preservation of ecosystems, restoration of them and induction of natural regeneration (Conanp, 2014), resulting in two SPECs in the same APFF:

Fringe that covers part of the northeast and central portions of the ejido and forming a wedge that runs to the south of it with an area of 823 ha.

Compact area that is found to the northwest end of the ejido with 14.96 ha. In total they comprise an area of 838 ha and represent 39.7% of the ejidal territory.

Monarch butterfly preservation subarea

This subarea includes areas of dense fir forest in good conservation status, at average altitudes of 3 220 to 3 430 m, which favors the seasonal establishment of the Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus L.). This area would allow productive activities of low environmental impact, forest management for ecosystem preservation and restoration, maintenance of existing roads and reintroduction of native species (Conanp, 2014). It is located in the central zone of the ejido, has an area of 45.8 ha and represents 2.17% of the ejidal territory.

Forest Recovery of the Nevado (SRBN) Subarea

It gathers fragmented pine forests (Pinus hartwegii Lindl.) with crown coverings of less than 50%. Here, forest management for the protection, conservation, restoration and preservation of ecosystems and forest sanitation would be developed (Conanp, 2014). It is a small portion to the northwest of the ejido, with 136.4 ha, corresponding to 6.4% of the ejidal territory.

Sustainable Use of Natural Forest Resources (SASRNF) Subarea

This subarea appears in the Conservation and Management Program of the APFF. They are dense and semi-dense forests of pine and fir in slopes smaller than 40% where sustainable use will be allowed. In these areas are allowed the opening of logging gaps, removal of dead timber and felled by natural phenomena for self-consumption, forest management, maintenance of gaps and roads (provided they are not expanded or paved), payment for environmental services and Federal and state support programs for conservation, protection and restoration of natural resources, and low environmental impact tourism (Conanp, 2014). It is located in the western part of the ejido running from north to south with an area of 689 ha, which corresponds to 32.7% of the ejidal territory.

Sustainable Use of Ecosystems Subarea

This subzone is a strip of 74.6 ha corresponding to 3.5% of the ejidal territory, which runs from south to north in the central and eastern part of the ejido, where there are relics of primary vegetation such as pine-fir, pine, pine-oak and gallery forest. Also, in this area there is a breach of access to the Cerro San Antonio that belongs to the western part of the Nevado de Toluca APFF. In this area, productive activities of low environmental impact, as well as restoration can be carried out. Commercial forest plantations with native species, forest management and tourism with low environmental impact are allowed (Conanp, 2014).

Sustainable Use of Natural Resources Subarea

This area of 523 ha, which is 24.8% of the ejido, is equivalent to two polygons in the southeast and southwest end; here coniferous forests are displayed in which Pinus and Abies species, as well as some broadleaves predominate. Productive activities with low environmental impact and restoration are granted, as well as forest and fire management, establishment of UMA and tourism with low environmental impact (Conanp, 2014).

Forest resources use scenario under the new regulatory framework

From the Sustainable Use of Natural Forest Resources (SASRNF) Subarea, potentially, 689 ha could be put under forest management, since from the change of the national park decree to Flora and Fauna Protection Area such options are opened; the main consequences of it would be:

An increment in the land under forest management with which the forest could get better when applying forestry labors of forest masses maintenance that at present have not been made as ejidatarios have not got interested in doing so as they consider it a restricted territory, as well as to have a greater control of forest plagues in the APFF.

A lower use of forest lands not included in the market and from which the inhabitants of SFO have traditionally taken timber for self-consumption.

A higher timber on foot sale, and therefore an income increase, where the main beneficiaries will be the contractors and service providers related to forest harvest, as far as the ejidatarios that do not get involved in the management and transformation of timber products.

Non-timber resources will have a greater pressure, as a result of wood cutting and extraction.

Conclusions

The maintenance of SRFUC has been allowed as an important component for the integration and social reproduction in San Francisco Oxtotilpan (SFO).

The established restrictions by the Nevado de Toluca Protected Natural Area (ANPNT) to harvest forest resources in SFO ejido have retarded the development of a culture related to the woods, which, by themselves, have not been the major factor to the small access of the ejido to the productive chain and the construction of a community enterprise culture. The possibility of the increment of land under forest harvest with the category change will be limited, as it is not a complete opening and will be subjected to a broad regulatory framework in environmental and forest matters, and therefore, harvest could be oriented towards sustainability in the benefit of the forest and their owners.

The category change of the ANPNT will produce qualitative and quantitative differences in the flows and processes in SRFUC-SFO, thus opening the chance to strengthen the forestry Matlatzinca culture and of the community enterprise, in order not to start pressures that could polarize the ejido, or the agrarian nucleus with the rest of the community institutions.

Female contribution is less than a third in the ejidal assembly and communal goods, which could be a sign of the feminization process, at least in decision taking. This implies to think the policies of forest management, conservation and environmental service payment with a gender perspective, inclusive, fair and sustainable.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to Conacyt for the financial supported granted to the Project “Tenencia de la tierra, uso y conservación de los recursos naturales en el Parque Nacional Nevado de Toluca”, 3503/2013CHT. Likewise, to Fabián Gerardo Moya García for making the maps; to Monserrat Estefany Alvarado Jaramillo and Azucena López Martínez for their support in field work and to Regina Trujillo Marín for reviewing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Álvarez I., P. 2006. Los recursos de uso común en México: un acercamiento conceptual. Gaceta Ecológica 80: 5-17. [ Links ]

Arnstein S., R. 1969. A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners JAIP 35(4): 216-224. [ Links ]

Bautista-Calderón, L. 2007. “Las vedas forestales en el México post-revolucionario”. Tesis de maestría en Estudios Regionales. Instituto de Investigaciones José María Luis Mora. México, D.F., México. 186 p. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2013. Apoyos 2013. http://www.conafor.gob.mx/aopoyos/index.php/inicio/app.apoyos#/detalle/2013/23 (6 de noviembre de 2015). [ Links ]

Gaceta de Gobierno, 2013. Solicitudes factibles del Programa para el pago por Servicios Ambientales Hidrológicos 2013. Gaceta de Gobierno del 5 de noviembre de 2013. Toluca, Edo. de Méx. http://legislación.edomex.gob.mx/sites/legislación.edomex.gob.mx/files/files/vigentes/nov053.PDF (6 de noviembre de 2015). [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (Conanp) 2014. Programa de Manejo del Área de Protección de Recursos Naturales Zona Protectora Forestal Los Terrenos Constitutivos de las Cuencas de los ríos Valle de Bravo, Malacatepec, Tilostoc y Temascaltepec, México para consulta pública de conformidad con el artículo 65 de la Ley General del Equilibrio Ecológico y la Protección al Ambiente. Semarnat. [ Links ]

Gamboa M., C. y M. Gutiérrez S. 2008. “Derechos Indígenas” Estudio Teórico Conceptual, de Antecedentes e Iniciativas, presentadas en la ILX Legislatura y en los Dos Primeros Años de Ejercicio de la LX Legislatura. Primera Parte. Cámara de Diputados. LX Legislatura. México, D. F., México. 115 p. [ Links ]

García F., E. 2006. Conservation from below: Sociecological system in natural protected areas in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. Tesis de Doctorado en Ciencias Ambientales. Instituto de Ciencia y Tecnologías Ambientales. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Barcelona, España. 252 p. [ Links ]

García-Frapolli, E y V. M. Toledo M. 2008. Evaluación de sistemas socioecológicos en áreas naturales protegidas: Un instrumento desde la economía ecológica. Argumentos, Nueva Época Año 21 (56): 103-116. [ Links ]

Kawulich, B. 2006. La observación participante como método de recolección de datos. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 6 (2), Art. 43. http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs0502430 (29 de enero de 2015). [ Links ]

Merino P., L. y E. Martínez A. 2015. A vuelo de pájaro. Las condiciones de las comunidades con bosques templados en México. Conabio., México D. F., México. pp. 188. [ Links ]

Ostrom, E. 1990. El gobierno de los bienes comunes. FCE, UNAM, IIS, CRIM. México, D. F., México. 395 p. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2016. Acuerdo por el que se da a conocer el Resumen del Programa de Manejo del área natural protegida con categoría de Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Nevado de Toluca, Diario Oficial de la Federación del 21 de octubre 2016. Ciudad de México, México. http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5457780&fec ha=21/10/2016 (30 de octubre de 2016). [ Links ]

Thomé O., H., 2016. Turismo rural y sustentabilidad. El caso del turismo micológico en el Estado de México. In: Carreño, M. y G. V. A Yaneth. (coords.). Ambiente y patrimonio cultural. UAEM. Toluca, Edo. de Méx., México. pp. 43-69 [ Links ]

Walker, B., S. Carpenter, J. Anderies, N. Abel, G. S. Cumming, M. Janssen, L. Lebel, J. Norberg, G. D. Peterson and R. Pritchard. 2002. Resilience management in social-ecological systems: a working hypothesis for a participatory approach. Conservation Ecology 6(1):14. [ Links ]

Received: October 21, 2015; Accepted: October 03, 2016

texto em

texto em