Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.7 no.37 México Set./Out. 2016

Articles

Utilization of non-timber forest products in the high mountain forests of central Mexico

1Instituto de Ciencias Agropecuarias y Rurales, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. México. Correo-e: sfrancom@uaemex.mx

2Programa de Postgrado en Desarrollo Rural, Colegio de Postgraduados. México.

The forms of exploitation of three Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) of the high mountain forests of central Mexico are described: pink snowberry (Symphoricarpos microphyllus), moss (Thuidium delicatulum var. delicatulum) and edible mushrooms (Fungi kingdom). The research was carried out in the Nevado de Toluca Flora and Fauna Protection Area in the San Bartolo Oxtotitlán ejido in the municipality of Jiquipilco, State of Mexico, through surveys, semi-structured interviews, transects along the extraction routes, random sampling of the flora and participative observation. The results showed that, in the case of moss, it is extracted and exploited by people outside the community, and therefore the locals receive no significant benefits from this activity. As for the pink snowberry, it is exploited by a few families in the community, who are the main beneficiaries. Access to the harvesting of wild edible mushrooms is free, and it is practiced by most of the local population; although in the past this activity was only for purposes of self-consumption, today it is evolving toward commercialization through intermediaries. The forms of utilization of each resource vary in terms of their temporality, demand and commercialization channels.

Key words: High-mountain forests; edible wild mushrooms; non-timber forest products; sustainable management; Symphoricarpos microphyllus (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Schult.) Kunth; Thuidium delicatulum var. delicatulum (Hewd.) Schimp

Se describe la forma de aprovechamiento de tres Productos Forestales No Maderables (PFNM) en los bosques de montaña alta del centro de México: vara de perlilla (Symphoricarpos microphyllus), musgo (Thuidium delicatulum var. delicatulum) y hongos comestibles (reino Fungi). La investigación se realizó en el Área de Protección de Flora y Fauna Nevado de Toluca y en el ejido de San Bartolo Oxtotitlán, municipio Jiquipilco, Estado de México, a través de encuestas, entrevistas semiestructuradas, transectos por las rutas de extracción, muestreos aleatorios de flora y observación participativa. Los resultados mostraron que, en el caso del musgo, son personas externas a la comunidad quienes realizan su extracción y aprovechamiento; y, por tanto, los pobladores locales no reciben beneficios significativos por dicha actividad. Respecto a vara de perlilla su recolección la llevan a cabo unas cuantas familias de la comunidad, quienes son las principales beneficiarias. La recolecta de hongos silvestres comestibles es de libre acceso y la practican la mayoría de los pobladores locales; cabe señalar que, si bien, antes esta actividad se destinaba al autoconsumo, en la actualidad está transitando hacia la comercialización, a través de intermediarios. Las formas de aprovechamiento de cada recurso varían en función de su temporalidad, demanda y canales de comercialización.

Palabras clave: Bosques de montaña alta; hongos silvestres comestibles; productos forestales no maderables; manejo sustentable; Symphoricarpos microphyllus (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Schult.) Kunth); Thuidium delicatulum var. delicatulum (Hewd.)Schimp)

Introduction

Non-Timber Forest Resources (NTFR) are vegetal species of forest areas that are susceptible of exploitation, due to their potential usefulness. Non-Timber Forest Resources (NTFR) refer to any part of these species being extracted or utilized for their service to the environment (Wong et al., 2001).

According to the Secretaría del Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Department of the Environment and Natural Resources) (Semarnat, 2014), the exploitation of the NTFRs in Mexico surpasses 70.5 tons; prevalent among these resources being commercialized are soil (62 %), resins (17.4 %) and medicinal plants, edible mushrooms and shrubs (19.1 %). The main resources collected in the State of Mexico are medicinal plants and edible mushrooms, followed by resins and soil (Semarnat, 2005a, 2005b).

Studies on NTFRs are scarce. The Comsión Nacional Forestal (National Forestry Commission) (Conafor, 2010) created a catalogue of major non-timber species in Mexico. Coronel and Pulido (2011) analyzed the possibility of preserving and utilizing the palm tree (Brahea dulcis (Kunth) Mart.) in the state of Hidalgo. Martínez et al. (2007) studied the useful flora o the coffee plantations of the Northern Sierra of Puebla and identified species that can be commercialized, including medicinal and edible plants. In southern Mexico, Martínez et al. (2011) assessed the effect of the utilization of chamaedorea (Chamaedorea quezalteca Standl. & Steyerm.) at the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve in Chiapas; Sánchez and Valtierra (2003) have documented research on Chamaedorea spp. at the Montes Azules Biosphere Reserve; Levy et al. (2002) characterized the traditional use of the spontaneous flora of the Lacandona rainforest in Lacanhá, Chiapas.

In the State of Mexico, Martínez et al. (2015) carried out a study of fruits and edible seeds which includes 40 fruit families and 138 fruit species. Arana et al. (2014) describe the obtainment of strains and the production of the inoculum of five wild edible mushroom species of the high mountains of central Mexico. Lara et al. (2013) recorded the traditional knowledge of wild mushrooms among the Otomi community of San Pedro Arriba, in Temoaya municipality. Franco et al. (2012) registered the wild edible mushrooms of Nevado de Toluca, while Franco and Burrola (2010) wrote a compendium and a taxonomic characterization of edible mushrooms of Nevado de Toluca.

Besides the exploitation of the NTFRs rural social organizations have also been studied, as in the case of bay laurel (Litsea glaucescens Kunth) leaves (Montañez et al., 2011); chamaedorea (Chamaedorea spp.) (Sánchez and Valtierra, 2003), and pink snowberry (Symphoricarpos microphyllus (Humb. & Bonpl. ex Schult.) Kunth) (Mendoza et al., 2011; Mendoza et al., 2012; Monroy et al., 2007). These researches describe the extraction process and commercialization of the resources and the forms of participation by various social stakeholders.

The purpose of the present study was to characterize the forms of exploitation of three NTFRs of the high mountain areas of the State of Mexico: pink snowberry, moss and wild edible mushrooms.

Materials and Methods

High-mountain forests are distributed at an altitude of 3 500 masl, and predominant species are Pinus hartwegii Lindl. (Hartweg’s pine) and Abies religiosa (Kunth) Schltdl. et Cham. (Sacred fir) (Endara et al., 2013). Pink snowberry, moss and edible mushrooms are abundant in this region (De Beer and McDermott, 1989). These products are subject to differentiated extraction dynamics; comparative analysis made it possible to identify similarities and differences in the extraction and commercialization processes of each product.

The study of wild mushrooms and Symphoricarpos microphyllus was carried out in the Nevado de Toluca Flora and Fauna Protection Area (NTFFPA), where there is a significant extraction of these resources. However, because it is a protected area, there is no considerable exploitation of moss (Thuidium delicatulum W. P. Schimper in B.S.G., 1852); therefore, this activity was researched at the San Bartolo Oxtotitlán ejido. This community shares ecological characteristics with Nevado de Toluca in terms of environmental conditions and of the organization of farmers’ communities.

NTFFPA is located in the southern-central State of Mexico and has a surface area of 53 590 hectares, comprising Almoloya de Juárez, Amanalco de Becerra, Calimaya, Coatepec Harinas, Temascaltepec, Tenango del Valle, Toluca, Villa Guerrero, Villa Victoria and Zinacantepec municipalities (Figure 1). Pine, Sacred fir and alder forests and alpine vegetation are prevalent. Despite its being a protected area, most of Nevado de Toluca is communal property, and the locals usually extract timber (wood and firewood) and non-timber (pink snowberry, mushrooms, earth and medicinal plants) forest products (DOF, 1937).

APFFNT=NTFFPA. Source: División Política del Estado de México; scale: 1:250 000 (Conabio, 1995).

Figure 1 Location of the Nevado de Toluca Flora and Fauna Protection Area and of Jiquipilco municipality.

The San Bartolo Oxtotitlán ejido belongs to Jiquipilco municipality; it is located in central State of Mexico, between Jocotitlán, Villa del Carbón, Temoaya and Ixtlahuaca municipalities (Figure 1). The predominant vegetation corresponds to conifers (pine and Sacred fir) and to certain oak species. The main economic activities of the local population are trade, the provision of services and, to a lesser extent, rain-fed agriculture. Besides, they extract wood, moss, edible mushrooms, medicinal plants and soil (GEM, 2004).

In 2008, information was collected to analyze the extraction of NTFPs on Nevado de Toluca through the application of 165 surveys in the communities of Agua Blanca, Buenavista, San José Contadero, El Varal, La Peñuela, La Puerta, Loma Alta, Raíces and San Román, all of which are ejido-based. The survey was structured around eight information cores: general data of the locality, data of the interviewees, characteristics of the family unit, economic activities, non-timber forest resources, timber forest resources and regulations for the extraction of resources.

The study on pink snowberry required the application of 12 semi-structured interviews applied to key informants (harvesters and a trucker) between January and October, 2013. Almost half of the 25 people involved in the activity were interviewed; the questions were based on four major cores: characteristics of the informer, knowledge regarding the extraction of the resources, workings of the social organization and participation in distribution and commercialization.

In addition, three transects were carried out -one for each locality-, and three samples of plants were taken from each, adding up to a total of nine. The routes were selected based on those followed by the harvesters who are familiar with the paths to where the plants are most abundant. The sites in each transect were selected at random and corresponded to those where the harvesters were going to collect the snowberry twigs. The sample is not representative of the entire area of communities studied, for those areas where no twigs were cut were excluded. For this reason, the sampling sites are typical of the extraction areas where the plants are most abundant, but they are not representative of the entire area where pink snowberry is present, as this is distributed in a heterogeneous manner; areas where snowberries were scarce were left out of the study.

The length of the transects was determined by the distance that the harvesters were going to travel. The transect at La Peñuela was 3.2 km long; it began 3 km away from the community and ended at the distance of 6.2 km. The transect in Buenavista began at 2.8 km and ended at 3.5 km. In Contadero, the transect was very close to the town, beginning at 1.5 km and ending at 2.5 km.

Pink snowberry grows in heterogenous patches in the forest. The species is characterized by growing in clusters, in areas with anthropic disturbance (Matesanz and Valladares, 2009). Due to these characteristics, the decision was made to select the sampling site at random in those places where it is harvested.

The product was quantified before its extraction, and the total number of shrubs per square meter, their height, number of twigs per plant and the maturity of the branches (shoot, young or ripe) were recorded. Once this information was recorded, the harvesters were allowed entry, and the total number of twigs cut per shrub was counted. The rolls of twigs were weighed and measured to verify whether they met the quality features demanded by the buyer. The species was determined at the laboratory of the Instituto de Ciencias Agropecuarias y Rurales, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (Institute of Agricultural and Rural Sciences of the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico).

The research on moss included 20 semi-structured interviews to key informants (harvesters, business owner and a trucker). The questions were integrated into the same basic cores as in the study of the pink snowberry.

During the months of November and December, 2012, 2013 and 2014, 10 transects were carried out in the area of extraction of moss -Cerro de La Bufa, in the San Bartolo Oxtotitlán ejido- using a GPS; the extraction techniques were identified through direct observation; the extracted amount was quantified, and the quality of the harvested resource was determined.

Based on the moss samplings, the percentage of exploitation per square meter, the weight, the surface area extracted and the quality of the bundles were estimated. For this purpose, ten 25 m2 plots were delimited at random, and the percentage covered by moss and its quality were calculated. Once this information was collected, the harvesters were given access, and the amount of moss extracted per square meter was quantified in order to verify whether the Official Norm NOM-01-SEMARNAT-1996 was being met (DOF, 2003b). The moss species extracted was identified at the Instituto de Biología of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (Institute of Biology of the National Autonomous University of Mexico).

As for the study of the extraction of wild edible mushrooms, based on the surveys applied in 2008, 13 harvesting rounds were carried out together with the key informers in order to obtain references of the location of the mushrooms, general data of the undergrowth, cutting techniques, common names of the mushrooms and forms of organization for the harvesting. Once the amount of mushrooms was estimated, the specimens were taken to the laboratory of the Centro de Investigación en Recursos Bióticos de la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (Center for Research on Biotic Resources of the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico) for their taxonomic identification.

Results and Discussion

Regulations for the extraction of NTFPs

The Normas Oficiales Mexicanas (Mexican Official Norms) (NOM) in matters of NTFPs are an environmental policy instrument that allows regulating the access to them and their exploitation. These norms establish that there must be consent from the landowners for the extraction of the resource. And the social stakeholders (both within and outside the communities) are responsible for managing this consent (in the case of the study documented herein, the Comisionado de las Tierras Comunales (Commissioner of the Communal Lands) is in charge of doing so). Subsequently, the buyer processes the extraction permits and the issuing of guides and invoices before the regional delegation of Semarnat in order to safeguard the legality of the resource extracted for commercial purposes.

The survey revealed that edible mushrooms and pink snowberry are the NTFPs extracted in the largest amounts in the region of Nevado de Toluca. The exploitation of pink snowberry, utilized for the manufacture of rustic brooms, is regulated via the NOM-005-SEMARNAT-1997 norm, which indicates the phenologic stage at which the exploitation must take place: “In order to promote the exploitation (of the branches) of the group of plants of the same age and size, only the extraction of a maximum of 60 % of the stalks ready for harvest shall be allowed. While the plant groups are in the flowering and seeding periods, only the same percentage must be exploited, in order to favor their reproduction from the seeds” (DOF, 2003a).

The ideal time for the extraction of pink snowberry is between May and August (Monroy et al., 2007). However, in the study area, it is harvested all year around: in the Buenavista community it is extracted from January to June; in La Peñuela, from May to June, and in San José Contadero, from August to October.

The extraction of moss has not been extended to all the high- mountain forest areas, as it depends on the abundance and quality of the resource, as well as on the accesibility to the extraction areas. The San Bartolo Oxtotitlán ejido has a surface of 1 625 ha, of which 200 were authorized in 2012 for intensive extraction (Semarnat, 2012). The NOM-01-SEMARNAT-1996 norm establishes that: “Moss must be exploited in patches or strips with a maximum width of 2 m, along the contour of the terrain, extracting a maximum of 50 % of the stock in each exploited site, in order to ensure its regeneration. The same site must not be exploited again until it has recovered completely.... The exploitation at the edges of roads, rivers, creeks and water bodies in general must be carried out leaving a 2 m wide protective strip in order to prevent erosion problems” (DOF, 2003b).

The extraction of edible mushrooms is regulated by the NOM-010-SEMARNAT-1996 norm, which establishes the procedures, criteria and specifications for the exploitation, transportation and storage of the mushrooms: “The exploitation of mushrooms will be subject to the following criteria and technical specifications: only fruiting bodies will be utilized at the ripe harvesting stage, being identified by their button shape, size and opening, according to the species to be exploited. The dry leaves that cover the mushoom must be removed gently; the fruiting body must be cut at ground level, and the site from which it was extracted must be covered in order to protect the mycellium” (DOF, 1996).

The season for the extraction of the mushrooms tends to vary in terms of the fruiting time of each species, although it is more intense in the summer. According to the data obtained, the mushrooms are harvested mainly for self-consumption, but there is a growing demand in the market. The regulations are little known, and the commercialization of the protected species is carried out illegally, as in the case of the white pine mushrooms (Tricholoma magnivelare (Peck) Redhead); pancitas or pambazos (penny buns, Boletus edulis Bull., Fr.), the yellow chanterells or duraznillos (Cantharellus cibarius Fr.), the morel or chile seco (Morchella esculenta Fr.), and the black morels known as elotillo (Morchella conica Pers.), colmenilla (Morchella costata (Vent.) Pers.) and morilla (Morchella elata Fr.), all of which may be productively endangered (DOF, 1996).

Location of the extraction sites

The extraction sites of the NTFPs are closely related to the type of forest. The snowberry grows at the edges of the Sacred fir forests, in disturb areas close to the roads and agriculture plots, as well as in ravines with steep slopes (Monroy et al., 2007; Matesanz and Valladares, 2009). Moss develops in Sacred fir forests with high levels of humidity (Conabio, 2012). Mushrooms grow in the pine, oak and -particularly- Sacred fir forests (Franco et al., 2012), where a larger variety and abundance is found (Franco and Burrola, 2010).

Characteristics of the NTFRs for commercialization

The selection of the resources for commercialization depends on the demands of the buyer. The pink snowberry branches must be at least 1.20 m long, with a diameter of over 0.5 cm, a dark brown color and a vigorous appearance, without signs of dehydration or flaking in their bark. Moss must be of a deep sage green or a similar hue, with minimum 2 cm height, a healthy appearance, without dead leaves, seeds or other herb species. The mushrooms must be frech, without marks or signos of decay, dehydration or excess dirt.

Extraction techniques

The extraction techniques affect the propagation and regeneration of organisms. According to Hartmann and Kester (1985), snowberry branches must be cut diagonally in order to promote the growth of both the shoots and the plant. Three techniques for the extraction of moss were identified: a) the use of a machete to detach it from the ground and harvest as cleanly as possible; b) the use of a piece of raffia, which is fastened and tensed with both hands and passed underneath the moss in order to detach it, and c) uprooting with the fingers. The mushrooms are pulled out by hand, breaking their stem at ground level (Franco and Burrola, 2010).

Preparation of the NTFPs

The harvesters are mainly men (92 %). In the case of snowberry, after the branches are cut, rolls of 200 to 220 twigs are tied together; the number depends on the quality-if it is 200, this is because there is a larger proportion of high-quality ripe material. Occasionally young twigs are placed at the center of the roll in order to equal the thickness of optimal quality rolls.

Moss is harvested only by men. Once “carpets” have been obtained, squares are formed and placed inside wooden crates measuring 30 cm in height, 40 cm in width and 30 m in length. When the crates are full, the bundles are bound together using branches as supports. Mushrooms are harvested during the early hours of the morning; men, women, adults and children participate indistinctly. The harvested mushrooms are transported in chiquihuites or baskets to allow airing and prevent rotting. At the end of the day, they are sorted by to their common names.

Storage and transportation

The pink snowberry is harvested in agreement with the business owner and a local stocker, who puts together the required number of rolls. He determines the loading sites, the mount of rolls to be supplied and the cost of the transaction. The La Peñuela ejido is the only one with permission by Semarnat to exploit the snowberry. The product harvested in the Buenavista and Contadero ejidos is commercialized as if it were included in this permit, which, in a strict sense, renders its exploitation illegal. The agreed number of rolls is transported to the political delegations of Mexico City for the public street cleaning service.

The bundles of moss harvested in the ejido are piled at the edge of the roads to be picked up later and placed on automotive vehicles for transportation. The harvesters load up the material and at the same time keep record of the total number of bundles collected by each person. The loaded trucks are concentrated at a particular spot in the ejido and depart simultaneously toward the place where they will commercialize, as the sales invoice must cover the total number of transported bundles.

In the case of edible mushrooms, these are basically destined to self-consumption and, to a lesser extent, to commercialization. This is a family activity; once the mushrooms have been sorted, they are taken to the local markets to be sold.

Commercialization of NTFPs

The commercialization process of pink snowberry depends on the demand generated by the Gobierno de la Ciudad de México (Government of Mexico City, GDF). The government issues tenders for the snowberry to be supplied within a certain time. These tenders establish the characteristics that the twigs must meet. For example, in the 2012 tender, the Comité Delegacional de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Prestación de Servicios de la delegación Coyoacán (Purchase, Rental and Service Provision Committee of Coyoacán delegation) published the following: “Purchase of 1.20 to 1.50 m high snowberry twigs in bales, each bale consisting of 25 rolls, and each roll comprising 50 twigs, for the January-June 2012 period, to support the jobs of traditional sweepers who sweep by hand the streets of this delegation (Coyoacán). Sum to be payed: 5 000 000.00 MXN (five million pesos 00/100) for 7 194 bales of snowberry. Coyoacán, Mexico, January 13, 2012” (Anastacio et al., 2015).

This tender established a price of 695.00 MXN per bale. A bale consists of 1 250 twigs, and therefore, a roll of 200 twigs was worth 1.20 MXN. The average transportation costs were of 0.64 MXN per roll, and the business owner paid 23.00 MXN to the local stocker. This implies that the business owner had a net income of 87.56 MNX per roll (78.7 % of the value of the roll sold to GDF. Out of the 23.00 MXN received, the local stocker paid 17.00 MXN per roll to the harvesters’ leader, and therefore received a surplus of 6.00 MXN (5.4 % of the total value of the roll). The harvesters’ leader, in turn, had to pay 10.00 MXN to the harvester; therefore, his profit was 7.00 MXN per roll (6.3 % of its total value). Payment to the harvesters amounted to a mere 8.9 % of the final price of pink snowberry.

In 2013, the price per roll ranged between 10.00 and 15.00 MXN, according to its quality. An inexperienced harvester extracted 10 poor-quality rolls per day (with more young than ripe twigs) and received an income of 100.00 MXN; an experienced harvester obtained up to 25 rolls per day and earned 250.00 MXN. When the harvester had family or friendship ties with his leader, the latter paid him up to 17.00 MXN per roll.

The commercialization of moss responds to demand by the local and regional markets. The ejido grants the business owner authorization to extract the moss in exchange for a sum in cash, established by the Commissioner of the Communal Lands. In 2012 and 2013, the payment received annually by the ejido was 15 000.00 MXN. The production value was distributed as follows: the ejido obtained 3 MXN per extracted bundle; each harvester received 10.00 per bundle; the harvesters’ leader who organized, recorded and oversaw the harvest earned 2 MXN per bundle; the business owner had a profit of 8 MXN per bundle, and the shopkeeper at the wholesale market received 20 MXN per bundle. A truck loaded with 450 bundles implied an income of 1 350.00 MXN for the Commissioner of the Communal Lands; the harvester earned 200 MX for 20 bundles; the harvesters’ leader earned 900 MXN for the total of bundles; the business owner had a surplus of 3 600 MXN, and the shopkeeper at the wholesale market earned 9 000 MXN.

The commercialization of edible mushrooms is subjected, to a large extent, to the supply of the product and to the demand generated in the local markets. It was not possible to estimate the cash flow generated as a result of its exploitation, since the value of the commercialized amount is determined by the species, with prices ranging between 20 and 250 MXN per kilogram.

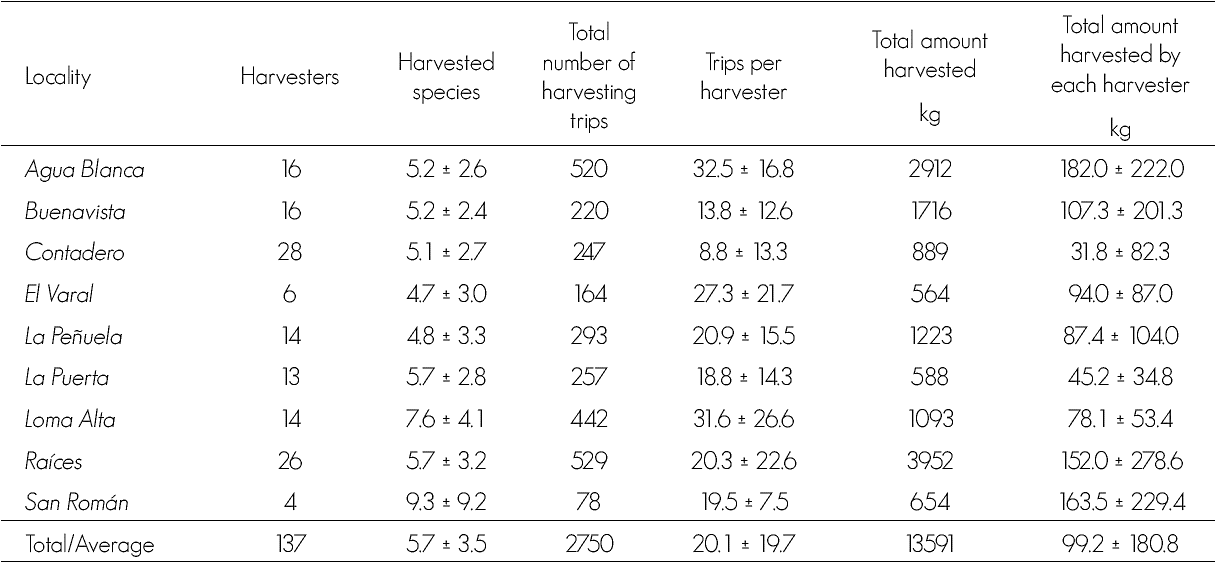

Based on the rounds made in each locality, it was estimated that a little over thirteen tons of mushrooms were harvested annually, and 140 (84 %) of the 165 interviewees harvested mushrooms mainly for self-consumption. The communities where this activity was most prevalent were: Raíces, Agua Blanca, La Peñuela, Buenavista and Loma Alta (Table 1). 77 mushroom species of edible wild mushrooms were identified at NTFFPA in the study, although an average of five taxa were harvested by each family (Franco et al., 2012; Franco and Burrola, 2010).

The highest percentage of utilization results when the heads of the family serve as guides in the harvesting, leading the children and their mothers (Figure 2).

The term “nuclear family” refers to harvesting by the members of the direct family; the term “extended family” refers to participation not only by the nuclear or direct family but also by in-laws, friends and neighbors.

Figure 2 Percentage of extraction of edible mushrooms by groups in the study locations, 2008.

Social stakeholders in the exploitation of NTFPs

Three groups of social stakeholders who participate in the exploitation of NTFPs were identified: a) governmental sector and institutions, b) businesspersons and intermediaries, and c) the local population.

The local population should be the primary subject of governance and of the preservation of the natural resources; however, it does not often have a key position in the exploitation of these resources; as Leff (2010) points out, decision making often falls on other stakeholders.

Governance of the resources must be defined by their owners with the support of governmental institutions (Semarnat, Profepa, Secretaría de Medio Ambiente del Gobierno del Estado de México (Department of the Environment of the Government of the State of Mexico) or of any other social stakeholder involved (universities, non-governmental organizations, professionals or others) in order for the exploitation to be sustainable and to thereby ensure the regeneration of vegetal populations as well as compliance with the laws, the NOM norms and Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Neither the harvesters who make their living on this exploitation nor the business owners who obtain the largest profits can be excluded. The term “stakeholders” is the one that best defines the social agents with an interest or responsibility in the preservation of natural resources.

According to Hasan (2001), poverty, lack of interest, disorganization, lack of financial support and lack of knowledge of the ecological importance of these resources, may be causing the profits from their utilization to go to people who are alien to the community. In the case of the exploitation and commercialization of moss and pink snowberry, the particularities of the market determine the low participation and the lack of interest of the local population.

A study by the International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO) on the sustainable utilization and commercialization of a selected group of NTFPs to support the artisanal industry and the development of the rural communities (in the Phillipines) points out that, although various social stakeholders are involved in the process, only a few participate actively in the commercialization of their products. In the case of the Phillipines, the inhabitants do not have any other source of income or the necessary means to perform any other role in the utilization of the resources. And those who do have the knowledge required to disseminate the products are the ones who obtain the largest profits (ITTO, 2012). In the studied communities, the exploitation of NMFPs is a complementary activity that may involve additional income for the inhabitants of the region, but which do not have a significant impact on their livelihood conditions. Under such circumstances, given the particularities of the market, this activity has little appeal for them.

The exploitation of NTFRs is very variable. That of pink snowberry and, above all, of moss, coincides with the statement of the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO, 2004) in the sense that there are communities whose inhabitants do not extract the resources directly and do not exercise the adequate governance for their preservation. External private stakeholders organize themselves to exploit these resources and appropriate the largest part of the production value.

The extraction of edible mushrooms continues to be a family activity that benefits the communities, although this situation has changed in the last few years as a result of the increase in the demand for the population of large cities.

The harvesting should adjust to the ecological temporality, regeneration and productivity of each resource, which do not always correspond to the economic cycles ruled by the demand, or to the social and cultural processes that oppose to them (Leff, 1995). As for the snowberry, its exploitation is not limited to the best time according its phenologic calendar. The harvesting of moss responds to the demand in the urban areas of the State of Mexico and Mexico City during Christmastime. And the harvesting of edible mushrooms is determined by the rainy season.

Article 27 of the Political Constitution of the Mexican United States points out that: “The nation shall at all times have the right to impose upon private property the modalities dictated by the public interest, as well as to regulate, for social well-being, the exploitation of the natural elements that are susceptible of appropriation, in order to carry out an equitable distribution of public wealth, to watch over its preservation, and to achieve balanced development of the country and the improvement of the living conditions of the rural and urban populations” (Segob, 2016). The governmental institutions do not always comply with this constitutional precept, nor do they favor the engagement of the social stakeholders in the proper use and preservation of the natural resources.

In the present study it was observed that Semarnat does not monitor the harvesting of mushrooms or of pink snowberry to ensure that it is carried out according to the regulations. As for moss, the process is monitored, probably because of its short temporality.

The rural communities that own the forests play a key role in the conditions for the preservation of the resources (Merino, 2004). In the documented research, the local population was observed not to show interest in exploiting moss or pink snowberry. This is because they devote themselves to other activities, they have no knowledge of the market, and no internal organizational mechanisms of the ejidos and localities exist to carry out the extraction. As a result of this lack of interest, external stakeholders are allowed to perform it in exchange for a sum of money; for example, in 2013 the business owner paid 8 000 MXN for the extraction of pink snowberry. This sum was destined to “community projects” and “expenses of the Commissioner of the Communal Lands”. If it had been distributed among the more than 300 communal land holders, it would have been a minimal income per capita. In the case of moss, we verified that the community ceded the exploitation of the resource to business owners, who do not hire locals, and therefore the profits for the community amounted only to the payment made to the Commissioner of the Communal Lands for the extraction permit (15 000 MXN); this sum was also not distributed among the communal land holders and was left over for “social projects”.

An important finding was that communities do not exercise adequate governance and they hand over the exploitation to outsiders, who extract the resources without proper supervision; this endangers the regeneration of the snowberry and moss populations. In the exploitation of mushrooms there is also no supervision by communal or other authorities. However, there is no evidence that the harvesting of the sporomes endangers the preservation of the species.

According to Requena (2014), success in the governance of natural resources entails participation by the stakeholders not only at a local level, such as communities, but also in institutions, such as the agencies of the state and federal governments. In the case of moss and the pink snowberry, we observe the absence of governance for their sustainable exploitation, which involves great responsibility of the governmental institutions at every level, as these are in charge of guaranteeing the application of laws and legal regulations, not to mention the responsibility of ensuring that the present generations will meet their needs without endangering the ability of future generations to satisfy theirs.

The comparative analysis in the exploitation of NTFPs takes into account various aspects: natural (temporality), social (use, gender, level of participation by the community and social stakeholders) and economic (type of market and distribution channels).

The NTFP market

The harvesting of snowberry twigs for the manufacture of rustic brooms occurs almost throughout the year, without respecting the seeding (March to June), blooming (July to September) or fruiting (October to February) seasons established by the phenologic calendar of the species. The cutting complies with the percentage established by the norms, not so the recommendations on cutting techniques. The harvesting is carried out predominantly by men, and the level of participation by the locals is limited to a few harvesters and local leaders (Commissioner of the Communal Lands and the members of the Communal Land Holders’ Assembly) who grant permission for its exploitation. The sale of the pink snowberry corresponds to a monopsonic market, with a single buyer (the Government of Mexico City). It is therefore a buyer’s monopoly which imposes its conditions upon the sellers due to its influence and its economic power (Ávila, 2004). As Sainz (2001) points out, the distribution channel is indirect, short, with intermediaries (the local stocker and the business owner) between the owner of the resource and the final consumer.

The extraction of moss corresponds to a short temporality. The entire production is sold to shopkeepers of the Mexico City Wholesale Market. The extraction of the resource complies with the regulations currently in force, in terms of the conditions of the plants, percentage of cutting, and cutting procedure. The activity is in charge of male workers. The external social stakeholders establish contact with the Commissioner of the Communal Lands in order to manage authorization and pay for the extraction rights established by the Communal Land Holders’ Assembly. The sale of moss is an oligopsony, with a very small number of buyers who determine the price of the product (Ávila, 2004). Its distribution channel is through wholesale, with at least two intermediaries between the producer and the final consumer. In many cases, the wholesalers become specialized, depending on the supply of the resources (Sainz, 2001).

The mushrooms are harvested during the rainy season (May to October). Of the 77 species cited for Nevado de Toluca, only two are included in the list of protected species: pancitas (penny buns, Boletus edulis) and elotitos (black morels, Morchella elata) (Franco et al., 2012). The main destination of edible mushrooms is self-consumption, with a growing tendency toward their commercialization. It is a family extractive activity in which men, women and children participate.

Unlike the extraction of snowberry twigs and moss, which notably are remunerated activities, the harvesting of mushrooms does not generate an income and is carried out sporadically, according to the time availability of the members of local families. When the mushrooms are commercialized, they are sold in an oligopsonic market, and the distribution channel is usually direct-from the harvester to the final consumer and, eventually, to the local shopkeepers (Sainz, 2001).

In recent years, the demand of mushrooms has increased, favoring the emergence of distribution chains (retailers and wholesalers) in which it is possible to identify the intervention of a stocker (retailer) or a wholesaler with the intervention of two other intermediaries (Miquel, 2008), or the presence of a local stocker who will later commercialize them in the city of Toluca.

Conclusions

The communities that own the high-mountain forests of central Mexico are not exercising the governance of their forest resources, in whose sustainable exploitation they are not sufficiently interested; they also lack an organization of their own for the direct extraction of pink snowberry or moss. These two NTFPs are being exploited through social organization processes dominated by external social stakeholders (business owners), who keep the largest economic profits, while the profits for the local population are minute or non-existent. There is little monitoring of the groups of harvesters by the local population and of the governmental institutions, a situation that endangers the regeneration of the species.

Edible mushrooms were originally extracted by local families solely for self-consumption, but the harvesting of these species is becoming a commercial activity directed to regional and national markets. Their exploitation is not monitored by local authorities or by Semarnat; however, pressure on the resource is low so far.

Semarnat and other government organisms restrict themselves to the approval of extraction permits and to their administrative follow-up, but they do not verify compliance with the norms; this may lead to harvesters damaging the resources in situ due to poor cutting techniques or to excessive extraction.

Governance over natural resources is not a unique prerogative of the communities that own them. The sustainability and preservation of the resources requires the participation of a series of social stakeholders, such as governmental institutions at all levels, professionals, NGOs, university academics, harvesters, business owners, and all those who may have a vested interest or responsibility in the status of natural resources. However, both the owners and the State have unavoidable responsibilities for the preservation of natural resources, given that these are a subject of interest for the present society as a whole and a heritage for the future generations.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contribution by author

Nancy Diana Anastacio Martínez: definition of the research topic, selection of study units and survey of field information, analysis of data and structuring of the document; Sergio Franco Maass: selection of study units, structuring of the manuscript and review and analysis of the data, particularly with regard to edible wild mushrooms; Estaban Valtierra Pacheco: supervision of the field work, analysis of the data, particularly in relation to the processes of extraction of “perlilla” stick and revision of the manuscript; Gabino Nava Bernal: analysis of the data and revision of the document in relation to the processes of extraction of moss.

Referencias

Anastacio, N., Valtierra, E., Nava, G. y Franco, S. 2015. Extracción de perlilla (Symphoricarpos microphyllus H.B.K.) en el Nevado de Toluca. Madera y Bosques 21(2): 103-15. [ Links ]

Arana, Y., C. Burrola, R. Origel, y S. Franco. 2014. Obtención de cepas y producción de inóculo de cinco especies de hongos silvestres comestibles de alta montaña en el centro de México. Revista Chapingo, Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 20(3):213-226. [ Links ]

Ávila, L. 2004. Introducción a la economía. Apuntes Núm. 31. Escuela Nacional de Estudios Profesionales Aragón, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. 3a ed. Plaza y Valdés. México, D.F., México. 393 p. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio). 2012. Mugos, hepáticas y antoceros. Conabio. http://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/especies/gran_familia/plantas/musgos/musgos.html (9 de junio de 2015). [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (Conabio). 1995. Sistema Nacional de Información sobre Biodiversidad. Conabio. http://www.conabio.gob.mx/informacion/gis/ (1 de junio de 2015). [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2010. Catálogo de recursos forestales maderables y no maderables, áridos, tropicales y templados. Semarnat. http://www.conafor.gob.mx/biblioteca/Catalogo_de_recursos_forestales_M_y_N.pdf (9 de junio de 2015). [ Links ]

Coronel M. y M. Pulido. 2011. ¿Es posible conservar y usar la palma Brahea dulcis (Kunth) Mart. en el estado de Hidalgo, México? In: Manual de herramientas etnobotánicas relativas a la conservación y el uso sostenible de los recursos vegetales. Red Latinoamericana de Botánica (1): 103-10. [ Links ]

De Beer, J. and J. Mc Dermott. 1989. The economic value of non-timber forest products in SE Asia. 2nd Edition. Netherlands Committee for the IUCN. Amsterdam, The Netherlands. 157 p. [ Links ]

Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF). 1937. Decreto que reforma, deroga y adiciona diversas disposiciones del diverso publicado el 25 de enero de 1936, por el que se declaró Parque Nacional la montaña denominada “Nevado de Toluca” que fue modificado. Semarnat. 19 de febrero de 1937. México, D.F., México. pp. 47-62. [ Links ]

Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF) . 1996. NOM-010-SEMARNAT-1996 Que establece los procedimientos, criterios y especificaciones para realizar el aprovechamiento, transporte y almacenamiento de hongos. 28 de mayo de 1996. México, D.F., México. 28 p [ Links ]

Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF) . 2003a. NOM-005-SEMARNAT-1997. Que establece los procedimientos, criterios y especificaciones para realizar el aprovechamiento, transporte y almacenamiento de corteza, tallos y plantas completas de vegetación forestal. Semarnat. 23 de abril de 2003. México, D.F., México. 31 p [ Links ]

Diario Oficial de la Federación (DOF) . 2003b. NOM-01-SEMARNAT-1996. Que establece los procedimientos, criterios y especificaciones para realizar el aprovechamiento, transporte y almacenado de musgo, heno y doradilla. Semarnat. 23 de abril de 2003. México, D.F., México. 5 p. [ Links ]

Endara, A., R. Calderón, G. Nava andS. Franco . 2013. Analysis of fragmentation processes in High-mountain forest of the Centre of México. American Journal of Plant Sciences 4(3):697-204. [ Links ]

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). 2004. Categorías de los productos forestales no maderables. FAO. http://www.fao.org/documents/es/detail/155970 (25 de febrero de 2015). [ Links ]

Franco, S. yC. Burrola . 2010. Los hongos comestibles del Nevado de Toluca. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. Toluca, Edo. de Méx., México. 147 p. [ Links ]

Franco, S. , C. Burrola y Y. Arana. 2012. Hongos silvestres comestibles: un recurso forestal no maderable del Nevado de Toluca. Ediciones y Gráficos Eón. Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México. Toluca, Edo. de Méx., México. 342 p. [ Links ]

Gobierno del Distrito Federal (GDF). 2012. Adquisición de varada de perlilla. Comité Delegacional de Adquisiciones, Arrendamientos y Prestación de Servicios. Delegación Coyoacán. México, D.F., México. 4 p. [ Links ]

Gobierno del Estado de México (GEM) Gobierno. 2014. Plan Municipal de Desarrollo Urbano de Jiquipilco. Periódico Oficial del Gobierno Constitucional del Estado de México. Gobierno del Estado de México. http://legislacion.edomex.gob.mx/sites/legislacion.edomex.gob.mx/files/files/pdf/gct/2004/feb273.pdf (9 de septiembre de 2014). [ Links ]

Hartmann, I. y D. Kester 1985. Propagación de plantas. CECSA. México, D.F., México. 760 p. [ Links ]

Hasan, M. 2001. La pobreza rural en los países en desarrollo. Su relación con la política pública. Fondo Monetario Internacional. Washington, DC, USA. 27 p. [ Links ]

International Tropical Timber Organization (ITTO). 2012. Project technical report: Assessment of marketing of non-timber forest products, Los Baños, Laguna Philippines. Proyecto pd448-07: Utilización sostenible y comercialización de un grupo seleccionado de productos forestales no maderables para apoyar la industria artesanal y el desarrollo de las comunidades Rurales (Filipinas), ITTO. http://www.itto.int/files/user/pdf/PROJECT_REPORTS/Assessment%20of%20Marketing%20 NTFPs%20-%20PD%20448-07%20R2%20(I).pdf (14 de marzo de 2016). [ Links ]

Lara, V., A. Romero yC. Burrola . 2013. Conocimiento tradicional sobre los hongos silvestres en la comunidad otomí de San Pedro Arriba, Temoaya, Estado de México. Agricultura, Sociedad y Desarrollo 10: 305-333. [ Links ]

Leff, E. 1995. ¿De quién es la naturaleza? Sobre la reapropiación social de los recursos naturales. Gaceta Ecológica 37: 28-35. [ Links ]

Leff, E. 2010. Discursos Sustentables. 2a ed. Siglo XXI Editores. México, D.F., México. 270p. [ Links ]

Levy, S., R. Aguirre, M. Martínez y A. Durán. 2002. Caracterización del uso tradicional de la flora espontánea en la comunidad lacandona de Lacanhá, Chiapas, México. Interciencia 27(10):512-520. [ Links ]

Martínez, A., V. Francisco, M. Mendoza y A. Cruz. 2007. Flora útil de los cafetales en la sierra norte de Puebla, México. Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 78:15-40. [ Links ]

Martínez, R., M. González, M. Pérez, P. Quintana y L. Ruiz. 2011. Evaluación del aprovechamiento foliar en Chamaedorea quezalteca Standl. & Steyerm. (Palmae), en la reserva de la biosfera el Triunfo, Chiapas, México. Agrociencia 45(4): 507-518. [ Links ]

Martínez, I., M. Rubí, A. González, D. Pérez, O. Franco y A. Castañeda. 2015. Frutos y semillas comestibles en el Estado de México. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 6(2): 331-346. [ Links ]

Matesanz, S. y F. Valladares. 2009. Plantas ruderales. Ciencia y Sociedad 390: 10-1. [ Links ]

Mendoza, C., M. López, D. Rodríguez, A. Velázquez y F. García. 2012. Crecimiento de la vara de perlilla (Symphoricarpos microphyllus H.B.K.) en respuesta a la fertilización y altura de corte. Agrociencia 46(7): 719-729. [ Links ]

Mendoza, B., F. García , D. Rodríguez y S. Castro. 2011. Radiación solar y calidad de planta en una plantación de vara de perlilla (Symphoricarpos microphyllus H.B.K.). Agrociencia 45(2): 235-243. [ Links ]

Merino, L. 2004. Conservación o deterioro. El impacto de las políticas públicas en las instituciones comunitarias y en los usos de los bosques en México. Semarnat, INECOL, CCMSS. México, D.F., México.320 p. [ Links ]

Miquel, S., F. Parra, C. Lhermie y J. Miquel. 2008. Distribución comercial. 6a ed. ESIC. Madrid, España. 487p. [ Links ]

Monroy, R., G. Castillo y H. Colín. 2007. La perlita o perlilla Symphoricarpos microphyllus H.B.K. (Caprifoliceae) especie no maderable utilizada en una comunidad del Corredor Biológico Chichinautzin. Morelos, México. Polibotánica 23: 23-36. [ Links ]

Montañez, M., E. Valtierra y S. Medina. 2011. Aprovechamiento tradicional de una especie protegida (Litsea glaucescens) en Sierra de Laurel. Aguascalientes, México. Ra Ximhai 7(2):155-172. [ Links ]

Requena, C. 2014. Gobernanza. Reto de la relación Estado-Sociedad. LID Editorial Mexicana. México, D.F., México. 166p. [ Links ]

Sainz, V. 2001. La distribución comercial: opciones estratégicas. ESIC. Madrid, España. 497 p. [ Links ]

Sánchez, D. y E. Valtierra . 2003. La organización social para el aprovechamiento de la palma camedor (Chamaedorea spp.) en la selva Lacandona, Chiapas. Agrociencia 37 (5): 545-552. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Gobernación (Segob). 2016. Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos. Dirección General Adjunta del Diario Oficial de la Federación. XXII edición. México, CDMX., México. pp. 53-64. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2014. Anuario Estadístico de la Producción Forestal 2013. Semarnat. http://www.SEMARNAT.gob.mx/sites/default/files/documentos/forestal/anuarios/anuario_2013.pdf (9 de junio de 2015). [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2012. Asignación del código de identificación para el aprovechamiento de recursos forestales no maderables y ejecución del Estudio Técnico. Delegación Estado de México. Oficio Núm. DFMARNAT/3845/2012. México, D.F., México. pp. 1-5. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2005a. El medio ambiente en México: en resumen. http://app1.SEMARNAT.gob.mx/dgeia/informe_resumen/pdf/0_info_resumen.pdf (1 de junio de 2015). [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2005b. Informe de la situación del medio ambiente en México. Capítulo 5. Aprovechamiento de los recursos forestales, pesqueros y de la vida silvestre. http://app1.SEMARNAT.gob.mx/dgeia/informe_04/05_aprovechamiento/cap5for_1.html (1 de junio de 2015). [ Links ]

Wong, J., K. Thornber and N. Baker. 2001. Resource assessment of non-wood forest products. Non-wood Forest Products. Rome, FAO. 124 p. [ Links ]

Received: June 06, 2016; Accepted: October 15, 2016

texto em

texto em