Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.7 no.34 México Mar./Abr. 2016

Article

Direct organogenesis for in vitro propagation of Quillaja saponaria Molina in Southern South Americac d

1 Campo Experimental Chetumal. Centro de Investigación Regional Sureste. INIFAP. México.

2 Facultad de Ciencias Forestales. Centro de Biotecnología. Universidad de Concepción. Chile.

4 Laboratorio Silvoagrícola Vitroflora Austral, Universidad de Concepción. Chile.

Quillaja saponaria is an endemic tree species from four countries in South America. From its bark, saponins are extracted which are economically important molecules used in pharmaceutical, industrial and agricultural purposes. In the present study the effect of hormonal components on the morphogenic capacity of Q. saponaria from caulinary segments from adult trees were evaluated. Murashige and Skoog (MS) culture medium supplemented with nine concentrations of 3-indole butyric acid (IBA) and 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) was used. A completely randomized balanced design with five replications was used; the experimental unit was a glass jar with four explants. The material was kept in a growth chamber at 25 ± 1 °C during day time and 22 ± 1 °C at night, with a light intensity of 3000 lux and a relative humidity of 60 %. Significant effects (P = 0.01) of the treatments on the variables number of outbreaks and caulinary elongation were determined. Duncan’s multiple range test confirmed that the treatments with significant differences were 1.0 mg L-1 of IBA and 2.0 mg L-1 BAP, for the number of shoots per explant and 1.5 mg L-1 of IBA and 0.5 mg L-1 BAP for caulinary elongation. The histological analyses revealed that the proliferation of meristematic structures was originated in the subepidermic tissue. These results support the scientific foundation of morphogenic competence of adult trees as sources of germ plasm for clonal propagation, which are crucial in a massive program of elite individuals.

Key words: Indole-3-butyric acid; physiological age; meristematic structures; Quillaja saponaria Molina; nodal segments; vitro-plantlets

Quillaja saponaria es una especie arbórea endémica de cuatro países de América del Sur. De su corteza, se extraen saponinas, moléculas de importancia económica utilizadas con fines farmacéuticos, industriales y agronómicos. En el presente estudio se evaluó el efecto de componentes hormonales sobre la capacidad morfogénica de Q. saponaria, a partir de segmentos caulinares provenientes de árboles adultos. Se empleó el medio de cultivo Murashige y Skoog (MS) suplementado con nueve concentraciones de ácido indol 3-butírico (AIB) y 6-bencilaminopurina (BAP). Se utilizó un diseño completamente al azar balanceado con cinco repeticiones; la unidad experimental fue un frasco de vidrio con cuatro explantes. El material se mantuvo en una cámara de crecimiento a 25±1 °C en el día y 22±1 °C en la noche, a una intensidad lumínica de 3000 lux y una humedad relativa de 60 %. Se determinaron efectos significativos (P = 0.01) de los tratamientos sobre las variables número de brotes y elongación caulinar. La prueba estadística de rangos múltiples de Duncan ratificó que los tratamientos con diferencias significativas fueron 1.0 mgL-1 de AIB y 2.0 mgL-1 de BAP, para número de brotes por explante y 1.5 mg L-1 de AIB y 0.5 mg L-1 de BAP para la elongación caulinar. El análisis histológico evidenció la proliferación de estructuras meristemáticas a partir de tejido subepidérmico. Estos resultados respaldan los cimientos científicos de la competencia morfogénica de árboles adultos como fuentes de germoplasma para la propagación clonal, clave en un programa de masificación de individuos elite.

Palabras clave: Ácido indol 3-butírico; edad fisiológica; estructuras meristemáticas; Quillaja saponaria Molina; segmentos nodales; vitroplantas

Introduction

Quillaja saponaria Molina (Quillay) is an endemic tree of four South American countries: Chile, Bolivia, Peru and Ecuador (INDAP, 2000). In Chile its distribution bounded on the north by the parallel 30° 30’ south latitude, in the IV region of Coquimbo. The southern boundary is located north of the IX region around the city of Algol, 38° south latitude (Gallardo and Gastó, 1987).

According to the Catastro y Evaluación de los Recursos Vegetacionales de Chile (Land Registry and Vegetational Resources Assessment of Chile) (CONAF et al., 1997), Q. saponaria is part of the sclerophyllous forest type covering an area of 324 631 ha, equivalent to 2.6 % of the country’s native forests (Donoso and Escobar, 2006). From its wood and bark, saponins are extracted which are economically very important molecules used in pharmaceutical, industrial and agricultural endings (Kensil et al., 1991; Hoffmann, 1995). Currently, the high demand for its bark as the main source of saponins and land use change have reduced the presence of adult trees, particularly in the central area of Chile.

This situation was crucial to carry out a forestry and forest management project for the species, supported by a program of vegetative propagation (Prehn et al., 2003), in which protocols of morphogenic development models were designed to propagate vegetatively and massively adult Quillay trees, using seeds as explants as they have a high content of saponins of good quality and low toxicity (Prehn et al., 2003).

As an additional contribution to the in vitro propagation, in the present study a micropropagation technique known as direct organogenesis was tested. The effect of hormonal components on the morphogenic capacity of caulinary, apical and basal segments from adult trees were evaluated.

The practical utility of the method is to establish the differences and clarify aspects of the morphogenic competition from caulinary segments of adult individuals, which can be used as sources of germ plasm for clonal propagation.

Materials and Methods

The experiment was performed at the Laboratorio de Biotecnología Forestal (Laboratory of Forest Biotechnology) of the Universidad de Concepción, located in Concepción, Chile (36°46’ S and 73°03’ W), 500 km south of the capital. Concepción is a city and commune in south-central Chile, and is the capital of the VIII region of Bío Bío.

Culture medium

The basic medium for the culture was the MS (Murashige and Skoog, 1962) with macronutrients reduced to 1/2, supplemented with a combination of hormonal balance and indole butyric acid (IBA) and benzylaminopurine (BAP). As energy source, sucrose (30 g L-1) was added and the pH was adjusted to 5.8 with NaOH (sodium hydroxide); as gelling agent agar (7 g L-1) was added.

Vegetal material

Se utilizaron explantes provenientes de la zona apical y basal de árboles adultos, los cuales se colocaron en posición vertical en contacto directo con el medio nutritivo; se sembraron 180 explantes por cada réplica y fueron cultivados en frascos de vidrio (5 cm de alto x 4 cm de diámetro) y ubicados en una cámara de crecimiento bajo condiciones de luz continua (40 μmol·m-2·s-1) y temperatura (25±1 °C). Posteriormente, se efectuaron observaciones cada 15 días, en las que se registraron el tamaño y la coloración del explante; a las seis semanas de cultivo, se llevó a cabo una primera cuantificación de la presencia de puntos de crecimiento, número de brotes y elongación caulinar.

Experimental design and statistical analysis

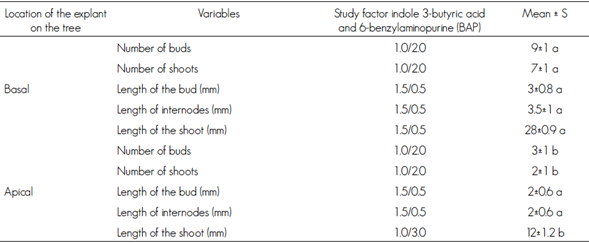

The experiment was established under a completely balanced randomized design with five replications and factorial arrangement of treatments. The studied factors were the indole 3-butyric acid (IBA) and 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) on three levels, for a total of nine treatments (Table 1). The experimental unit was a glass jar with four explants, which constituted 45 replicates per condition. After 90 days of culture, the number of buds, number of shoots and length of internodes per explant variables were evaluated. The information was subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA) through the PROC GLM SAS statistical program (Statistical Analysis System, 1999). Comparison of treatment means was made with the multiple range test of Duncan procedure, with a significance level of 5 %.

Histological study

For the histological analysis, six samples of explants with shoots were taken during the stages of proliferation and elongation Samples were fixed 24-48 hours in FAA [formalin (5 %) - acetic acid (5 %) - ethyl alcohol (90 %)]. Then, they washed with running water for 24 hours. Once washing was complete, the tissue was dehydrated in serial solutions of ethyl alcohol (50, 75, 85 and 95 %) every two hours. The samples were then passed three times by pure ethyl alcohol for two hours in the first two slides and all night in the final translation. Then three immersions were conducted in xylol for two hours in each slide, and embedded in paraffin three passes every two hours. The samples were included in paraffin blocks, which were performed in longitudinal and transverse cuts sections with a thickness of 5-8 microns with a Minot vertical sliding type microtome. Finally, each cut was adhered to a slide and stained with safranin astra blue 1 %. An Opton Axioskop microscope and images were used for observation of samples (40x), which were photographed with a Canon Power Shot G5 digital camera adapted to the microscope.

Results and Discussion

In woody plants in vitro propagation is more difficult to achieve for its structural condition and maturity processes associated with age. In this regard, three processes that explain the above mentioned are described: chronological aging, based on changes expressed in function of time; ontogenetic aging, related to the gradual and irreversible transition regulated under genetic control; and physiological aging, associated with the loss of vigor caused by hormonal changes, nutritional and environmental conditions (Pierik, 1990; Russell et al., 1990; Gutiérrez, 1995; Pacheco, 1995; Andrés et al., 2002). Specifically, the morphogenic capacity of the explant is strongly influenced by ontogeny, which varies according to the position of the plant material in the tree (Magini, 1984).

In the present study greater morphogenic capacity explants from the basal area (Figure 1A) were observed, which is attributable to differences in the ontogeny of the tissue where buds originate, and by the various hormone levels in the different areas of the tree. These results agree with those obtained by Fouret et al. (1986); Thanh et al. (1987) and Yeung et al. (1998), who demonstrated the existence of greater competition in basal morphogenic microshoots and better use of nutritional reserves for cell elongation.

A, B and C. Proliferation of multi- growth zones; D, E and F. Elongation of microshoots from basal origin.

Figure 1. Photographic sequence exhibiting proliferation and elongation of the Quillaja saponaria Molina caulinary segments at 120 days of cultivation.

Sánchez-Olate et al. (2005) and Hasbún (2006) indicate that basal ontogenically microshoots are younger and show a better morphogenic response, because they have been generated from dormant meristem tissues. Morisset et al. (2012) point out the importance of other factors such as the amount of water, light and carbohydrates that basal microshoots used from the parent material during their development. The apical microshoots origin had lower rates of proliferation and close caulinary elongation. Von Aderkas and Bonga (2000), Andrés et al. (2002), Fraga et al. (2002); Tang et al. (2004) and Ramarosandratanam and Van Staden (2005) suggest that differences in the responses of proliferation and elongation of the basal and apical microshoots could be linked to the existence of biochemical markers type and to differences in hormone levels within the donor tree.

According to the results of the ANOVA for the treatment factor, a significant effect (P <0.01, F = 77.46 and 12.82) was obtained on the variable of number of buds and for the length of internodes and buds. Specifically, for the variable number of buds T4 (1.0 / 2.0 mgL-1 of IBA / BAP) which originated a greater amount, with an average of seven shoots per explant (Table 2). In contrast, the T1 treatment (0.1 / 2.0 mgL-1 IBA / BAP) stimulated multiple points of growth (Figure 1A) and T5 (1.0 / 3.0 mgL-1 IBA / BAP) promoted buds with a rosette look and shape with plenty of surrounding callus (figures 1B and 1F).

Table 2 Comparative test between treatment means by Duncan’s multiple range test.

Different letters mean statistical significant differences (P < 0.01).

Consistent with these results, it is demonstrated and substantiated the role of auxin-cytokinin hormone relations as a key factor in controlling morphogenesis. In addition, consistent with those obtained in Persea americana Mill by Mohamed- Yasseen (1995); Pliego-Alfaro and Murashige (1988), and in Persea lingue Ness by Cob et al. (2010). Also, other studies agree that the organ induction effect of cytokinins is oriented to the formation of growth points, which reflected favorably with high proportions of cytokinin compared to auxin.

In several species it has been proved that as the concentration of cytokinin gets higher, a decrease in shoot length was found, until a rosette is formed (Sánchez-Olate et al., 2005; Rodríguez et al., 2003; Sotolongo et al., 2003). In this regard, Orellana (1998) notes that the auxin-cytokinin balance is crucial for the coefficient of proliferation.

The length of the microstems is favored by decreasing the concentration of cytokinin in the IBA / BAP relationship; the optimum was reached with the T9 treatment (1.5 / 0.5 mg L-1 of IBA / BAP) (figures 1C, 1D, 1E). In contrast, the microshoots that were grown in T5 (1.0 / 3.0 mgL-1 IBA / BAP) did not elongate, and rosette-shaped explants were observed (Figure 1B).

Specifically, those in the T9 treatment reached, on average, 28 mm long and those of the T5 treatment, 12 mm average (Table 2).

These results coincide with those obtained in Juglans regia L. (Scaltsoyiannes et al., 1997), Nerium oleander L. (Ollero et al., 2010) and Legrandia concinna (Phil.) Kausel (Uribe and Cifuentes, 2004). Authors show an increased cell elongation of lateral buds, by employing benzylaminopurine at low concentrations compared to auxin, attributable to decreased cell division and elongation of the tissue is promoted due to the action of auxin.

In this regard, Von Arnold (1988) notes that it is often necessary to reduce the dose of cytokinins in the nutrient medium to achieve an increase in the elongation of internodes, resulting in obtaining longest sprouts. Guohua (1998), Read and Preece (2003) cite that cytokinins in high concentrations stimulate the proliferation of multiple growth points; in contrast, auxins induce the elongation of the cell wall, which is reflected in a lengthening of the microshoots. Tamas (1995) points out that the effect on caulinary elongation due to the addition and hormonal concentration in the culture medium is differential for each type of hormone which becomes evident when the auxin- cytokinin ratio levels vary.

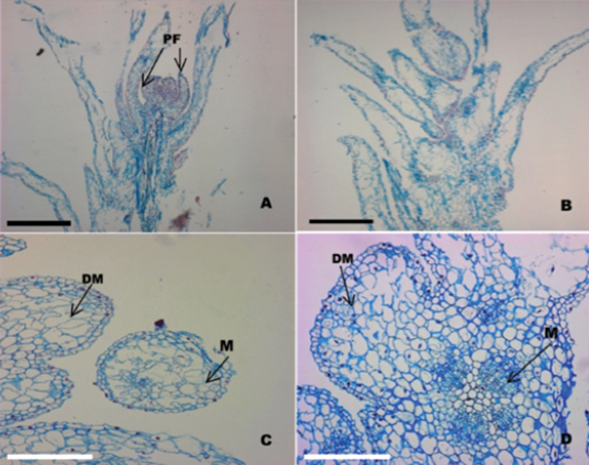

Histological analysis included transverse and longitudinal cuts; it corroborated the in vitro regeneration process through direct organogenesis (figures 2A, 2B, 2C and 2D).

A. Longitudinal section of a protuberance separated from the initial tissue showing the presence of developing leaf primordia (PF) (bar = 5 mm); B. Longitudinal section of a protuberance with leaf primordia after 45 days from the start of the culture (bar = 5 mm); C. Cross section of a caulinary apex showing the formation of the meristematic dome (MD) and the presence of a meristemoide (M) (bar = 8 mm); D. Longitudinal section of a caulinary apex; note the presence of meristematic dome (DM) and meristemoids (M) (bar = 8 mm).

Figure 2 Histological sequence of formation of protuberances from nodal segments of Quillaja saponaria Molina cultured in vitro (40x).

Figure 2A clearly shows a well-defined meristematic dome and leaf primordia. The meristematic dome is constituted by a layer of aligned surface cells, from which emerged the first pair of leaf primordia (figures 2B and 2C) that mark the beginning of the development of an adventitious vegetative shoot. Also, the processes involved in the formation of nodules became evident; it is observed that the main morphogenic activity of cells occurs in the tissues that make the meristematic region.

The results agree with those of Mitra and Mukherjee (2001) and Lara et al. (2003), who point out that the cells of the meristematic zones are originating caulinary sprouts, through an organogenic process. These meristematic structures are characterized by always staying in a juvenile condition and are susceptible to external signals of induction and cellular reprogramming. Therefore, the formation of areas with morphogenic activity keep present in meristematic zones (Figure 2D), which by mitotic processes, first, form a meristematic dome and then the primordial leaves. This is attributable to high concentrations of hormones in the meristematic regions that promote active cell division and expansion permanently. Moreover, the exogenous application of growth regulators in the culture medium directly affected the endogenous hormone levels and, therefore, the meristematic activity that resulted in an increase of cellular development processes.

Conclusions

The in vitro culture of Quillaja saponaria is successful in the stages of multiplication and elongation of caulinary microshoots explants from the basal area. Specifically, by applying an optimal ratio of indol3-butyric acid (IBA) and 6-benzylaminopurine (BAP) in the nutrient medium, the development of adventitious organogenesis was stimulated, which is corroborated by histological analysis. On the other hand, the contribution of this study lies in affirming the scientific foundation around the morphogenic competition explants from different heights of the donor tree. However, there are still questions on the subject, worthy of being incorporated in future studies. It is also required to optimize processes based on the replication of other assays under similar conditions.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the International Scholarship Program of the International Fellowships Fund (IFF) of the Ford Foundation scholarship granted to the first author for doctoral studies at the Universidad Austral de Chile and Universidad de Concepción. To the Escuela de Graduados of the Facultad de Ciencias Forestales y Recursos Naturales for the partial financial support for the purchase of chemicals used in the experimental phase. To the research staff of GenFor S.A. for the facilities, comments and suggestions during the development of the experimental phase.

REFERENCES

Andrés, H., B. Fernández and R. Rodríguez. 2002. Phytohormone contents in Corylusavellana L. and their relationship to age and other developmental processes. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 70 (2): 173-180. [ Links ]

Cob, J., A. M. Sabja, D. Ríos, A. Lara, P. Donoso, L. Arias and B. Escobar. 2010. Potencial de la organogénesis como estrategia para la masificación in vitro de Persea lingue en la zona centro-sur de Chile. Bosque 31(3): 202-208. [ Links ]

Corporación Nacional Forestal (CONAF). 1997. Catastro y Evaluación de los Recursos Vegetacionales Nativos de Chile. Informe Nacional. CONAMA, BIRF, Universidad Austral de Chile, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Universidad Católica de Temuco. Santiago, Chile. 88 p. [ Links ]

Donoso, C. y B. Escobar. 2006. Autoecología de las especies latifoliadas: Quillaja saponaria Mol. In: Donoso, C. (ed.). Las especies arbóreas de los bosques templados de Chile y Argentina. Autoecología. Ediciones Marisa Cuneo. Valdivia, Chile. pp. 545-555. [ Links ]

Fouret, Y., Y. Arnaud, C. Larrieu and E. Miginiac. 1986. Sequoia sempervirens (D. Don) Endl. as an in vitro rejuvenation model. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 16 (3): 319-327. [ Links ]

Fraga, M., M. Canal and R. Rodríguez. 2002. In vitro morphogenic potential of differently aged Pinus radiata D. Don trees correlates with polyamines and DNA methylation levels. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 70 (2): 139-145. [ Links ]

Gallardo, S. y J. Gastó. 1987. Estado y Planteamiento del cambio de estado del ecosistema de Quillaja saponaria Mol. Facultad de Agronomía, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Informe de Investigación. Sistemas en Agricultura. Santiago, Chile. 248 p. [ Links ]

Guohua, M. 1998. Effects of cytokinins and auxins on casssava shoot organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis from somatic embryo explants. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 54: 1-7. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, B. 1995. Consideraciones sobre la fisiología y el estado de madurez en el enraizamiento de estacas de especies forestales. Ciencia e Investigación Forestal 9(2): 261-276. [ Links ]

Hasbún, R. 2006. Monitorización Epi-genética del desarrollo y producción de plantas de castaño (Castanea sativa). Tesis Doctor en Biotecnología. Universidad de Oviedo. Oviedo, España. 234 p. [ Links ]

Hoffmann, A. 1995. Flora silvestre de Chile, zona araucana. 3a ed.. Ediciones Fundación Claudio Gay. Santiago, Chile. 257 p. [ Links ]

Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario (INDAP). 2000. INDAP en Cifras 1989- 1999. Desarrollo de la Agricultura Familiar Campesina. Santiago, Chile. pp. 72. [ Links ]

Kensil, R., U. Patel, M. Lennick and D. Marciani. 1991. Separation and characterization of saponins with adjuvant activity from Quillaja saponaria Molina cortex. Journal of Immunology 146: 431-437. [ Links ]

Lara, A., R. Valverde y L. Gómez. 2003. Histología de embriones somáticos y brotes adventicios inducidos en hojas de Psychotria acuminata. Agronomía Costarricense 27(1): 37-48. [ Links ]

Magini, E. 1984. Il ringiovanimento del materiale forestale di propagazione. In: Azienda regionalle delle Foreste (ed.). Propagazione in vitro: Ricerche su alune specie forestales. Roma, Italia. 298 p. [ Links ]

Mitra, S. and K. Mukherjee. 2001. Direct organogenesis in Indian spinach. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 67(2): 21-215. [ Links ]

Mohamed-Yasseen, Y. 1995. In vitro propagation of avocado (Persea americana Mill.). California Avocado Society Yearbooks 79: 107-111. [ Links ]

Morisset, J., B. Mothe, F. Bock, J. Breda and N. Colin. 2012. Epicormic ontogeny in Quercus petraea constrains the highly plausible control of epicormic sprouting by water and carbohydrates. Annals of Botany 109: 365-377. [ Links ]

Murashige, T. and F. Skoog. 1962. A revised medium for rapid growth an bioassay with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiologia Plantarum 15: 473-497. [ Links ]

Ollero, J., J. Muñoz, J. Segura and I. Arrillaga. 2010. Micropropagation of oleander (Nerium oleander L.). HortScience. 45(1) 98-102. [ Links ]

Orellana, P. 1998. Introducción a la propagación masiva. In: Pérez J., N. (ed.). Propagación y mejora genética de plantas por biotecnología. Instituto de Biotecnología de las Plantas. Santa Clara, Cuba. pp. 125-132. [ Links ]

Pacheco, J. 1995. Revigorización de material adulto de Pinus nigra Arn.: criterios morfológicos y moleculares. Tesis Doctor. Departamento de Biología de Organismos y Sistemas, Universidad de Oviedo. Oviedo, España. 200 p. [ Links ]

Pierik, R. 1990. Cultivo in vitro de las plantas superiores. Multiprensa. Madrid, España. 326 p. [ Links ]

Pliego-Alfaro F. and T. Murashige. 1988. Somatic embryogenesis in avocado (Persea americana Mill.) in vitro. Plant Cell Tissue and Organ Culture 12: 61-66. [ Links ]

Prehn, D., C. Serrano, C. Berrios and P. Arce-Johnson. 2003. Micropropagación de Quillaja saponaria Mol. a partir de semilla. Bosque 24: 3-12. [ Links ]

Ramarosandratanam, A. and J. Van Staden. 2005. Changes in competence for somatic embryogenesis in Norway spruce zygotic embryo segments. Journal of Plant Physiology 162: 583-588. [ Links ]

Read, P. and J. Preece. 2003. Environmental Management for Optimizing Micropropagation. Acta Hortic 616:49-58. [ Links ]

Rodríguez, R., M. Daquinta, I. Capote, D. Pina, Y. Lezcano y J. González. 2003. Nuevos aportes a la micropropagación de Swietenia macrophylla x Swietenis mahogami (caoba híbrida) y Cedrela odorata (cedro). Cultivos tropicales 24(3): 23-27. [ Links ]

Russell, J., S. Grossnickle, C. Ferguson and D. Carson. 1990. Yellow cedar stecklings: nursery production and field performance. Ministry of Forests, FRDA. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada. Report Num. 148. pp. 34-35. [ Links ]

Statistical Analysis System (SAS). 1999. SAS. Institute Inc. 1999. Versión 8. Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA. n/p. [ Links ]

Sánchez-Olate, M., D. Ríos y R. Escobar. 2005. La Biotecnología Vegetal y el Mejoramiento Genético de Especies Leñosas de Interés Forestal y sus Proyecciones en Chile. In: Sánchez-Olate, M. y D. Ríos . (eds.). Biotecnología Vegetal en Especies Leñosas de Interés Forestal. Departamento de Silvicultura. Facultad de Ciencias Forestales. Universidad de Concepción. Concepción, Chile. pp. 17-28. [ Links ]

Sotolongo, R., M. García, L. Junco, G. Geada y E. García. 2003. Micropropagación de Psidum salutare (Myrtaceae). Revista del Jardín Botánico Nacional 24(1-2): 245-250. [ Links ]

Scaltsoyiannes, A., P. Tsouipha, K. P. Panetsos and D. Moulalis. 1997. Effect of genotype on micropropagation of walnut trees (J. regia L.). Silvae Genetica. 46: 326-332. [ Links ]

Tamas, I. A. 1995. Hormonal regulation of apical dominance. In: Davies, P. J. (ed.). Plant hormones. Physiology, biochemistry and molecular biology. Kluwer Academic Publisher. Dordrecht, The Netherlands. pp. 572-597. [ Links ]

Tang, W., L. Harris, C. Outhavong and R. Newton. 2004. The effect of different plant growth regulators on adventitious shoot formation from Pinus virginiana Mill. zygotic embryo explants. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture 78(3): 237-240. [ Links ]

Thanh, T., D. Yilmaz and T. Trinh. 1987. In vitro control of morphogenesis in conifers. In: Bonga, J. and D. Durzan. Tissue culture in forestry. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. Dordrecht. The Netherlands. pp. 168-182. [ Links ]

Uribe M., 2000. Poliaminas y manipulación de la morfogénesis en el género Pinus L. Tesis doctoral. Universidad de Oviedo. Oviedo, Asturias, España. 178 p. [ Links ]

Uribe, M. y L. Cifuentes. 2004. Aplicación de técnicas de cultivo in vitro en la propagación de Legrandia concinna. Bosque 25(1):129-135. [ Links ]

Von Aderkas, P. and J. Bonga. 2000. Influencing micropropagation and somatic embryogenesis in mature trees by manipulation of phase change, stress and culture environment. Tree Physiology 20: 921-928. [ Links ]

Von Arnold, S. 1988. Tissue culture methods propagation of forest trees. Newsletter (Holland) 1(56): 1-13. [ Links ]

Yeung, E., C. Stasolla and L. Kong. 1998. Apical meristem formation during zygotic embryo development of white spruce. Canadian Journal of Botany 76: 751-761. [ Links ]

Received: October 21, 2015; Accepted: May 05, 2016

texto em

texto em