Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.7 no.34 México mar./abr. 2016

Article

1Campo Experimental Centro de Chiapas, Centro de Investigación Regional Pacífico Sur, INIFAP.

2 Área Agropecuaria y de Recursos Naturales. Universidad Nacional de Loja, Ecuador.

El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve (REBITRI) is at risk due to ignorance and the inadequate assessment of the important ecosystem services (SE) that it provides; the lack of information on the subject limits the design of strategies for their permanence. The aim of this study was to diagnose the offer, threats and conservation strategies of the SE that the reserve brings, from a representative watershed. It was developed in four stages: gathering available information; SE characterization through five workshops and 61 interviews with the participation of the local population; production of images of interest and, validation and feedback of results by local villagers. Eight types of SE, among which are the food, fiber and fuel and soil formation and retention were identified. Forests (61 % of the territory) are a priority supply of SE. The increase of the agricultural frontier, population growth, intense and erratic rains and government incentives are the main threats to forests. Among the strategies to ensure the supply of forest SE include payments for environmental services, community agreements and intercommunity for the preservation of resources, limiting agricultural burning, conservation practices cultivated soils, increase of human and social capital and improving the efficiency of land use for agricultural use.

Key words: Protected area; tropical montane cloud forest; natural resources conservation; watershed; El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve (REBITRI); ecosystem services

La Reserva de la Biósfera El Triunfo (REBITRI) está en riesgo por el desconocimiento e inadecuada valoración de los importantes servicios ecosistémicos (SE) que brinda; la falta de información sobre el particular limita el diseño de estrategias para su permanencia. El objetivo de este estudio consistió en diagnosticar la oferta, las amenazas y las estrategias de conservación de los SE que proporciona el lugar, a partir de una microcuenca representativa. Se desarrolló en cuatro etapas: recopilación de información disponible; caracterización de los SE a través de cinco talleres y 61 entrevistas con la participación de la población local; generación de imágenes de interés y, validación y retroalimentación de los resultados por los pobladores locales. Se identificaron ocho tipos de SE, entre los que destacan los alimentos, las fibras y los combustibles, así como la formación y retención de suelos. Los bosques (61 % del territorio) son prioritarios para el abastecimiento de SE. El incremento de la frontera agropecuaria, el crecimiento poblacional, las lluvias intensas e irregulares y los incentivos gubernamentales son las principales amenazas de estos ecosistemas. Entre las estrategias para garantizar el suministro de los SE destacan los pagos por servicios ambientales, acuerdos comunitarios e intercomunitarios para la preservación de los recursos, limitación de las quemas agropecuarias, prácticas de conservación de suelos cultivados, incremento del capital humano y social, además del mejoramiento de la eficiencia del uso agropecuario de la tierra.

Palabras clave: Área natural protegida; bosque mesófilo de montaña; conservación de recursos naturales; cuenca; Reserva de la Biósfera El Triunfo; servicios ecosistémicos

Introduction

In the last 50 years, man has drastically changed ecosystems more than at any other comparable time in history. During this period substantial net gains in human welfare and economic development were accomplished, at the expense of a high degradation (sometimes irreversible) of biodiversity on the planet, a situation that according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005), will become more evident during half of the XXIst century. Climate change is one of the great consequences, mainly due to the consumption of fossil fuels and land use change (Caparros, 2007; Galindo, 2009). Some policy measures to mitigate this problem is to reduce deforestation and promote the conservation of protected natural areas to be a highly cost effective way to reduce carbon emissions (Stern, 2007).

The El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve (REBITRI) was declared as such in 1992 and in the global context, it is considered an important area for the provision of a wide range of services to society and ecosystem regulations on the planet (Conanp, 2010).

López et al. (2011) confirms lo anterior the above for water resources. Because of its location in the mountain range and its unique vegetation cover of tropical montane cloud forest, it captures a lot of rain that becomes the main source of water supply and a key area for regulating the risks of flooding downstream on both sides of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas.

Paradoxically its existence is threatened due to ignorance and inadequate valuation that society and the three levels of Mexican government make of what the ES (Ecosystem Services) offer, which are utilized for their welfare without any recognition, much less pay per use; and also by the lack of studies showing the benefits derived from the conservation of this reserve. This situation leads to overexploitation of natural resources, which put at risk the sustained flow of ES over time, if not permanently destroyed (FAO, 2008).

The aim of this study was to conduct a participatory assessment of the offer, threats and conservation strategies of the SE in a representative watershed of the REBITRI, in order to identify management strategies and conservation potential applied at the level of the entire reserve.

Materials and Methods

Location and description of the study area

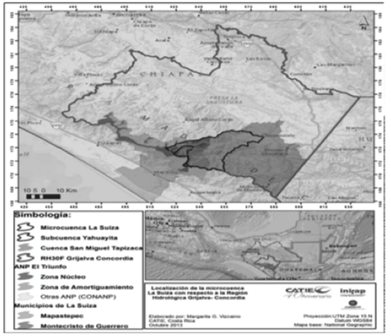

The research was conducted in the La Suiza watershed located in Guerrero and Mapastepec municipalities, in the state of Chiapas, Mexico (Figure 1), with a total area of 6 083.22 ha and a perimeter of 37.48 km. A large percentage of its territory (85.32 %) is located within the polygon of the El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve (REBITRI) on top of the Sierra Madre de Chiapas (Gutiérrez, 2013). Here prevails a wet and temperate semi-warm climate humid (INE, 1998), with altitudes between 1 000-2 600 m, an annual rainfall of 2 000-3 000 mm on the bottom and from 2 500 to 4 500 mm at the top, distributed from April to October. The annual average temperature is 18 to 22 °C at the bottom and 12 to 18 °C at the top.

The microwatershed gathers a population of 1 300 inhabitants, distributed in ejidos and private property; it is representative of the REBITRI in terms of high social marginalization, problems of deterioration (low productivity of productive activities, increasing deforestation, soil erosion, etc.) and frequent damage and increasingly more severe, caused by extreme precipitation (López et al., 2012).

Identification and assessment of ecosystem services

The proposed methodology to study the ES of REBITRI includes four phases (Figure 2).

Stage 1. It consisted of collecting available information on the study area, such as studies, stakeholders, fire and floods statistics, as well as government projects.

Stage II. During this time field data on the ES (types, provider actors, areas where they are generated, threats and possible strategies) were obtained through the completion of five participatory workshops and application of 61 interviews with the local population. The ES were identified and prioritized based on local perceptions and subsequently classified in groups of ES proposed by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (2005) identified as: Cultural, including the ES related to spirituality, education and recreation; Regulation, which refers to climatic stability, disease regulation and erosion; Provision, which considers food, water, timber, fiber, etc., and Sustenance which are those that are associated with basic ecological processes that ensure the functioning of ecosystems and the flow of the others, for example, primary production and biodiversity.

Stage III. During this phase, and with the participation of the population, images of the watershed and communities, ES- generating areas, vulnerable areas to threats and conflict zones were defined. With the support of a GPS and maps of the communities, the limit points were taken in the image of interest (López et al., 2012); and subsequently supported by the ArcGis 9.3 program and the digital elevation model (DEM) of 90 m resolution downloaded directly from the of SRTM DEM NASA page (Jarvis et al., 2008), the images were obtained. Particularly vulnerable areas were defined from the identification of areas of conflict where the slope is greater than 30 %, and land use is agriculture and game, in which there are high risks of landslides and erosion (Cubero, 2001; CNTP, 2003).

Stage IV. In this last part the results of the meetings obtained from the community assembly were presented, with the aim of validating them by the population or, when appropriate, to receive feedback.

Results and Discussion

Delimitation of territories and identification of ES

Within the 6 083.22 ha of La Suiza watershed there are 1 ES generating territories, of which three are ejidos that cover 46 % of the area, four locations with other types of tenure covering 45 % and four private properties totaling 9 % of the area. The Toluca ejido is the most extensive with 2 662.7 ha, equivalent to 39.7 % of the watershed. With the exception of Nueva Colombia and Laguna del Cofre the rest of the territories have their villages within it.

Figure 3 and Table 1 show the spatial distribution and statistics of the different land uses in the watershed, which were defined with the participation of each of the communities. Forests cover 55.7 and coffee cultivation 37.2 % of the total area.

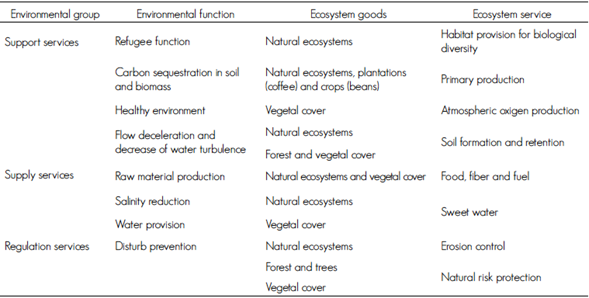

In order of importance, forest areas followed by planted with coffee were identified by the population as strategic for generating eight ES (Table 2), of which four belong to the group of Support, two to the Supply and two to Regulation. Particularly striking is the absence of recognition of the ES known as Cultural that are related to spirituality, education and recreation.

Table 2 Ecosystem goods and services identified by local actors in La Suiza microwatershed, Chiapas State.

Source: Adapted from Kandus et al. (2010).

Community perception of the value of forests in generating ES agrees with the premise that these associations are one of the most important biomes of the world for the goods and services they provide (Benites et al., 2007). The water supply conception is consistent with that reported by López et al. (2011) that, within the REBITRI, the infiltration capacity of one hectare is between 2.0-2.5 times greater than one hectare out of it.

It is worth noting that 33.3 % of those interviewed (n = 61) did not identify any kind of beneficiary of the ES; such is the case of Vista Alegre private property, which stood entirely in this percentage, which showed that the ignorance of the population is on the ES and its beneficiaries. The rest, 66.7 %, considers family as the primary beneficiary, followed by the town, the watershed, the city, the state, the country and the world.

No statistically significant association between providers and types of beneficiaries of the ES or between types of actors and types of ES was found, since the P value of the X2 of the statistic was 0.2980 for the first one and 0.0647 for the second. That is, both private properties and the ejidos are unaware of the ES as well as the areas where they are generated.

Toluca ejido excelled in identifying more types of beneficiaries. In order of importance the most frequently identified ES by the population were food, fiber and fuel, formation and retention of soil, erosion control, provision of fresh water and habitat. Although the population does not directly use the ES “formation and retention of soil” as with other such services, it is pointed out as a priority as it is directly related to the cultivation of coffee, maize and beans which are their main food resources, which is even more significant due to the low productive area available as it is inside El Triunfo Biosphere Reserve.

By linking land use and the ES of higher frequency, it is confirmed that forests are priority areas for the formation and retention of soil, and that soil, as it stores nutrients and moisture and supports plants, is a strategic resource for the production of food, fiber and fuel.

Ejidos are the most important lands that provide the identified ES as they own 57 % (1 922.4 ha) of the total forest area, of which Toluca contributes with 95 % (occupies 75.52 %), Puerto Rico 2.8 % (16.0 %) and Monte Virgen 2.2 % (44.33 %) (Table 1). In these ejidos, are administered renewable natural resources according to their customs in compliance with environmental laws of the country; this is done in a way which allows effective management on their use and management. However, in places such as Vista Alegre, Emiliano Zapata and Puerto Rico, the data in Table 1 indicate that the pressure for change in land use for growing coffee, corn and beans has significantly decreased forested areas; in the first case there are no forests, in the second there are only are relicts (10 ha) and in the third one, only 53.5 ha remain.

Forest land (3 389.25 ha) considered strategic in providing ES are composed of mist evergreen bushes, mountain rain forest, evergreen cloud forest, pine-oak-sweetgum forest, pine and oak and gallery and riparian forest (Rzedowski, 2006). These forests are unique in the world and its distribution in Mexico does not exceed two million hectares (approximately 1 % of the country). However, its high moisture requirements makes them very vulnerable to regional changes in climate caused by deforestation and excessive logging (Breedlove, 1981).

Identification of threats of supply of ES

The threat is a risk factor that compromises the safety of persons, ecosystem services and benefits (Cárdenas et al., 2008); the most important which lead to the supply of services identified by 80 % of respondents were: a) Change of land use for growing coffee, maize, beans and livestock, which are population activities associated with deforestation and forest fires; b) Population growth that fosters greater demand for land to meet family needs; c) more intense and erratic rains that generate higher erosion rates, directly damaging productive assets and indirectly infrastructure and development; d) government incentives that encourage land use change.

The X2 (P=0.0001) test indicated that such factors were differentially identified among the ejidos. For example, to Toluca (which has the largest area of forests) the most important are livestock, forest fires and slope, while for Monte Virgen (ejido with the smallest forest area), government policies, natural disasters and forest fragmentation.

With regard to land use from its natural aptitude, it was estimated that 5 % (314.9 ha) of the surface of the watershed should be used for agricultural purposes (corn, beans and livestock), 1 % (693.18 ha for farming coffee and 84 % (5 075.13 ha) for forest use (Figure 4). This analysis found that annual crops and livestock should not be practiced on land with slopes greater than 15 %, coffee cultivation on slopes no greater than 30 % and forests on slopes greater than 45 % (Cubero, 2001; CNPT, 2003).

When crossing the maps of current land use (Figure 3) and suitability for use according to the slope (Figure 4), it was determined that 2 552.47, which is equivalent to 42 % of the total area of the watershed, are ordered in the category of overuse or conflict (Figure 5), because productive activities (maize, beans and coffee) in areas that exceed the slope limits recommended in the map are practiced there.

Under these conditions of use, besides missing the ES generated by the forest, productive activities are not sustainable because the soil is exposed to intense degradation effects of water erosion.

Figure 6 shows that in 39 % of the area of the watershed there is a severe and very severe erosion rates of soil loss above the 50 t ha-1 yr-1 corresponding to the middle and lower parts where coffee and maize grows (FAO, UNEP and UNESCO, 1980). Maize is distinguished as the basis of food security of the local population and also because it grows on the most fragile soils that have poor coverage and slopes are 60 to 70 %. Coffee represents 95 % of household income on average and although its cultivation under shade protects the soil from raindrop impact, it is affected by runoff during the rainy season. This dynamic interaction between local population and ecosystems for the production of food from agriculture in areas not suitable for agriculture it is recorded as the main threat to the sustainable generation of ES at a local and global scale (Balvanera and Cotler, 2009).

The negative effects from the conflict of land use are accentuated because the area is classified as natural hazard occurrence of disasters landslides and flooding due to the presence of various factors that interact with each other, such as the shape and small size of their basins, the rugged terrain with steep slopes over short distances, intense and long-lasting rains, granitic rocks that produce coarse sediments and rocks with fragile joints and fractures (US Forest Service, 2007; Schroth et al., 2009).

Identification of possible management strategies and conservation of ES

The population identified 13 possible strategies for the management and conservation of the ES, which were validated in meetings of community assemblies; these include compensation for care and to restore forests through the payment of environmental services; establish community and intercommunity conservation agreements; avoid burning of cultivated maize soils; implement conservation practices to stop the erosion process of cultivated maize and coffee and build local capacity to implement conservation actions.

No significant association between types of actors and possible types of strategies for the management and conservation of ecosystem services was found; the X2 statistical P value was 0.9939.

Conclusions

Eight types of ES and seven groups of beneficiaries thereof were detected in the watershed, among which food, fiber and fuel and soil formation and retention outstand in the first one and the families of the watershed in the second. Forests which occupy 3 715 ha (61 %) of the territory of the watershed were considered priorities for the provision of the ES identified. Half of the forest area belongs to the ejidos where there is greater pressure for land use.

From the surface of the watershed, 42 % have conflicts in land use because productive activities (maize, beans and coffee) they are practiced in areas that exceed the limits of slopes recommended in the suitability map.

The main threats to forests in order of priority are the change of land use for agricultural activities, population growth, intense and erratic rains and government incentives that encourage land use change.

The population highlights the compensation for forest care and restoration through payment of environmental serves; community and intercommunity agreements for conservation; avoid burning of cultivated maize soils; implement conservation practices to stop the erosion process of cultivated maize and coffee lands and build local capacity to implement soils conservation actions, as strategies for the management of ecosystem services.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Fondo de Conservación El Triunfo A. C. the partial financing of the study and to the La Suiza watershed communities for their hospitality and support during the field data survey.

REFERENCES

Balvanera, P. y H. Cotler. 2009. Estado y tendencias de los servicios ecosistémicos, In: Capital natural de México, Vol. II: Estado de conservación y tendencias de cambio. CONABIO, México, D. F., México. pp. 185-245. [ Links ]

Benites, A., J. Campos J., J. Faustino, R. Villalobos y R. Madrigal. 2007. Identificación de servicios ecosistémicos como base para el manejo participativo de los recursos naturales en la cuenca del río Otún, Colombia. Recursos Naturales y Ambiente (55):83-90. [ Links ]

Breedlove, D. E. 1981. Introduction to the flora of Chiapas. California Academy of Sciences. San Francisco, CA, USA. 34 p. [ Links ]

Caparros G., A. 2007. El informe Stern sobre la economía del cambio climático. Ecosistemas 16 (1): 124-125. [ Links ]

Cárdenas, M., P. Choquevillca, J. P. Saavedra, G. Torrico y J. Espinoza. 2008. Construcción de mapas de Riesgo. Criterios metodológicos. La Paz, Bolivia. 50 p. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Plan Turquino (CNPT). 2003. Suelos, usos, conservación y mejoramiento. Manual técnico para las actividades agropecuarias y forestales en las montañas. Agrinfor 2003. La Habana, Cuba. 31p. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas (Conanp). 2010. Programa de Conservación y Manejo de la Reserva de la Biósfera El Triunfo. Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, México. 202 p. [ Links ]

Cubero, F. 2001. Clave de bolsillo para determinar la capacidad de uso de las tierras. Accs. MAG. Araucaria. 200. San José, Costa Rica. 19 p. [ Links ]

Galindo, L. M. (coord.). 2009. La economía del cambio climático en México. Síntesis. Semarnat. SHCP. México, D. F., México. 67 p. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, M. 2014. Pautas para una gestión integrada del agua con enfoque de género en la microcuenca La Suiza en Chiapas, México. Tesis Magister Scientiae. Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza. Turrialba, Costa Rica. 135 p. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Ecología (INE). 1998. Programa de manejo de la Reserva de Biosfera El Triunfo. México, D. F., México.109 p. [ Links ]

Jarvis, A., H. I. Reuter, A. Nelson and E. Guevara. 2008. Hole-filled seamless SRTM data V4. International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT). Palmira, Colombia. s/p. [ Links ]

Kandus, P., R. D. Quintana, P. G. Minotti, J. Oddi, C. Baigún, G. G. Trilla y D. Ceballos. 2010. Ecosistemas de humedal y una perspectiva hidrogeomórfica como marco para la valoración ecológica de sus bienes y servicios. http://www.academia.edu/4096009/ecosistemas_de_humedal_y_una_perspectiva_hidrogeom%c3%93rfica_como_marco_para_la_valoraci%c3%93n_ecol%c3%93gica_de_sus_bienes_y_servicios (16 de marzo de 2015). [ Links ]

López, W., R. Magdaleno, R. Reynoso y E. Salinas 2011. Conectividad hídrica entre municipios, cuencas y Reserva de la Biósfera El Triunfo, Chiapas, México: Potencial para la creación de un mercado local de agua. Folleto Técnico No. 5. INIFAP. Campo Experimental Centro de Chiapas. Ocozocoautla de Espinosa, Chiapas, México. 18 p. [ Links ]

López, W. , R. Magdaleno e I. Castro. 2012. Riesgo a deslizamientos de laderas en siete microcuencas de la Reserva de la Biósfera El Triunfo. Libro Técnico No. 7. INIFAP. Campo Experimental Centro de Chiapas. Ocozocoautla de Espinosa, Chiapas, México. 208 p. [ Links ]

Millenium Ecosystem Assessment. 2005. Ecosystem and human well-being: Biodiversity Synthesis. World Resources Institute, Washington, DC, USA. 31 p. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo de la Agricultura y la Alimentación, Programa de las Naciones Unidas para el Medio Ambiente, Organización de las Naciones para el Medio Ambiente (FAO, PNUMA y UNESCO). 1980. Metodología provisional para la evaluación de la degradación de los suelos. Roma, Italia. 86 p. [ Links ]

Organización de las Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo de la Agricultura y la Alimentación (FAO). 2008. Pago por servicios ambientales en áreas protegidas en América Latina. Programa FAO/OAPN. Informe de Avance No.1. Fortalecimiento del Manejo Sostenibles de Recursos Naturales en la Áreas Protegidas de América Latina. Santiago de Chile, Chile. 26 p. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 2006. Vegetación de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. 1ra. Edición digital. México, D.F., México. 400 p. [ Links ]

Schroth, G., P. Laderach, J. Dempewolf, S. Philpott, J. Haggar, H. Eakin, T. Castillejos, J. G. Moreno, L. S. Pinto and R. Hernández. 2009. Towards a climate change adaptation strategy for coffee communities and ecosystems in the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, Mexico. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change 14(7): 605-625. [ Links ]

Stern, N. 2007. Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change. http://www.sternreview.org.uk (12 de febrero de 2015). [ Links ]

USDA Forest Service. 2007. Landslides, channel erosion, and sedimentation in the Western Sierra Madre, Chiapas, Mexico, during hurricane Stan in 2005: a brief field review with recommendations. Washington, DC, USA. 24 p. [ Links ]

d Contribution by author. Walter López Baez: design and conduction of the project, planning with the communities, field work, data analysis and structuring of the manuscript; Byrom Gonzalo Palacios Herrera: design of the project, field work, land use map design and processing of interviews; Roberto Reynoso Santos: data analysis, discussion supported by literature review and editing of the manuscript following the instructions of the journal.

Received: June 15, 2015; Accepted: January 01, 2016

texto en

texto en