Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.7 no.33 México ene./feb. 2016

Articles

Tree diversity and structure of two stands in Pueblo Nuevo, Durango

1Instituto Politécnico Nacional, Centro Interdisciplinario de Investigación para el Desarrollo Integral Regional, Unidad Durango, México. Correo-e: liz _3626@hotmail.com

This study describes the structure and diversity of tree species in two stands with pine-oak temperate forests, located in the Chavarría Nuevo ejido of the community of Coscomate, in the municipality of Pueblo Nuevo, Durango. The vegetation was sampled using the method of four quadrants around a point. The structural parameters of dominance, frequency and dominance were estimated and used to determine the Importance Value Index for the tree taxa in each site; a diametric distribution histogram was obtained using the Weibull function. The diversity was estimated using the Shannon-Wiener index. The Euclidean distance was utilized to calculate the floristic similarity between the sites. 13 tree species belonging to five genera and five botanical families were recorded. The structural characteristics of the vegetation evidence that the vegetation of stand 1 is dominated by Pinus cooperi with scarcely any other tree species, while stand 2 shows a larger diversity, with a predominance of P. durangensis. Furthermore, this is the stand with the highest diversity (H'= 1.07 a 1.58). There is a low similarity between the two sites, despite their closeness and despite the fact that they are located at similar altitude intervals -an example of the ecological complexity of the Western Sierra Madre.

Keywords: Arbutus; temperate forest; Juniperus blancoi Martínez; Pinus; Quercus; Western Sierra Madre

El presente estudio describe la estructura y la diversidad de especies arbóreas de dos rodales con bosque templado de pino-encino, ubicados en la comunidad Coscomate, ejido Chavarría Nuevo, municipio Pueblo Nuevo, Durango. Se muestreó la vegetación por medio del método de cuadrantes centrados en un punto. Se calcularon los parámetros estructurales de dominancia, frecuencia y densidad, con los que se determinó el Índice de Valor de Importancia para los taxa arbóreos de cada sitio, y se obtuvo un histograma de distribuciones diamétricas mediante la función Weibull. La diversidad fue estimada por medio del índice de Shannon-Wiener. Se empleó la distancia euclidiana para medir la similitud florística entre los sitios. Se registraron 13 especies de árboles pertenecientes a cinco géneros y cinco familias botánicas. Las características estructurales de la vegetación evidencian que la del rodal 1 está dominada por Pinus cooperi con escasos elementos arbóreos acompañantes; mientras que la del rodal 2 es más diversa, en la cual P. durangensis tiene el mayor valor de importancia. Además, este es el que registra la diversidad más alta (H'= 1.07 a 1.58). La similitud entre ambos sitios es baja, a pesar de su cercanía y de situarse en intervalos de altitud similares, lo que constituye un ejemplo de la complejidad ecológica de la Sierra Madre Occidental.

Palabras clave: Arbutus; bosque templado; Juniperus blancoi Martínez; Pinus; Quercus; Sierra Madre Occidental

Introduction

Mexico has an extraordinary diversity of forests, which cover 33 % of its territory (Semarnat, 2012). Prominent among these are the temperate forests, one of the main types of vegetation in the country (Rzedowski, 2006); they are generally located in the middle and high portions of the mountains and area made up of Pinus, Abies, Pseudotsuga, Cupressus, Juniperus and Quercus vegetal communities or, occasionally, of mixed communities in various proportions (Challenger and Soberón, 2008). Mexico is the main center of diversification of pine species and has over 150 oak species.

24 Pinus taxa (46 % of the national total), as well as 54 Quercus (34 %) and 7 Arbutus taxa (100 %) are distributed in the Western Sierra Madre (WSM); they are the main physiognomic components of the forests in this region. Pine forests cover 12 % (30 197 km2) of the surface area of the WSM and are located at an altitude of 1 600-3 320 masl, while pine-oak forests occupy 30 % (76 265 km2) (González et al., 2012). Both types of vegetation are very diverse and develop in temperate semi-cold and temperate semi-dry climates. They have a great biodiversity and provide significant ecological and economic benefits (Semarnat, 2012).

Sustainable forest management requires having basic information about their structure and the elements that make them up. Knowledge of the structure of forest masses is essential for silvicultural management, as it determines the output of products and services, as well as the resilience and dynamics of the ecosystem under management (Wehenkel et al., 2014).

Knowledge of the diametric distribution of a site is a key decision making tool in forest management, as it provides information on the regeneration strategies and on the future tendency of the population (Uribe, 1984; Wright et al., 2003; Cao, 2004; Corral at al., 2015).

The makeup and diversity also allow a better understanding of the functional processes, as well as optimization of silvicultural management practices. Studies on the vegetation are one of the main supports for the planning, management and preservation of any ecosystem. In this regard, a planned floristic characterization or inventory must provide information at three different levels -1) specific wealth (alpha diversity); 2) species replacement (beta diversity), and 3) structure data- that is helpful to determine the conservation status of the studied areas (Villarreal et al., 2006). The purpose of this research was to learn about the diversity and structure of two adjoining stands whose vegetation corresponds to a temperate forest.

Materials and Methods

Study área

The study was carried out in the Coscomate community of the Chavarría Nuevo ejido, in Pueblo Nuevo municipality, Durango State. The substrate of the area is formed by Leptosol and Regosol soils over igneous rocky outcrops. The climate is sub-humid temperate [C(w)], with an annual precipitation of 800 to 1 200 mm, summer rains and mean temperatures ranging between 8 and 14 °C. The dominant vegetation consists of pine and pine-oak forests (González et al., 2007, 2012). Ecotourism activities are carried out in the community.

Sampling

Two adjoining stands were selected, with altitude intervals between 2 4000 and 2 555 masl and differing mainly in their predominant topoforms: intermountain valleys, lowlands and hillsides with mild and medium slopes in stand 1, and mountainsides with medium to steep slopes in stand 2 (Figure 1).

Four sampling sites were established at random in each locality, using the method of four quadrants around a point (Cottam and Curtis, 1956; Mitchell, 2007). This is one of the distance techniques most widely used for the study of vegetal communities, particularly forests, as it provides a useful and practical estimation of the structure, does not require area delimitation, and is less costly in terms of time and difficulty, for the study of the structure of forests in areas with a rugged topography. Furthermore, it is helpful for communities in which the plants are relatively spaced out. The method is more effective for forest studies (considering the sampling times) than for area studies (Mitchell, 2007).

A 100 m long line with five central sampling points separated by a distance of 20 m was drawn in the sampling sites. Each point was crossed with a perpendicular line so as to mark four quadrants, and the distance from the central point to the closest tree was measured. The data recorded for each individual include species, crown diameter, diameter at breast height diameter (DBH) and height. Only those individuals with a height equal to or above 1.5 m and a DBH of 1.30 m were considered. A total of four trees per central point -adding up to a total of 20 trees per site- were measured.

Data analysis

Parameters of density, dominance, frequency and the Importance Value Index (IVI) were calculated in absolute and relative values for the taxa in each site, using Mitchell's formulas (2007). The Weibull function was utilized to create diametric distribution histograms, which were evaluated through a chi-square goodness-of-fit test, using Statgraphics Centurion.

Species accumulation curves were obtained using EstimateS 8.2.0 software (Colwell, 2006), with the Chao 2, Jack 2 and Bootstrap estimators, for a reliable estimate of the maximum species richness of the area.

The alpha diversity was calculated using the Shannon-Wiener index (Magurran, 1988) and the Past 2.7 software (Hammer et al., 2001). This index expresses even importance values for all the species of the sample and is calculated using the following formula (Moreno, 2001):

Where:

Pi = i species proportion (relative abundance) in regard to the total abundance of the species found in each site

Pairs of sites were compared for similarity in the tree species composition by means of a cluster analysis with Euclidean distance, using the pair linking method.

Results and Discussion

Non-parametric estimators indicated the expected number of species per site (Figure 2). The lowest number -for 13 taxa- was estimated using the Chao 2 index, and the highest value -for 16 taxa-, using Jack 2. Based on these results, the sampling effort is appropriate in relation to the number of taxa recorded.

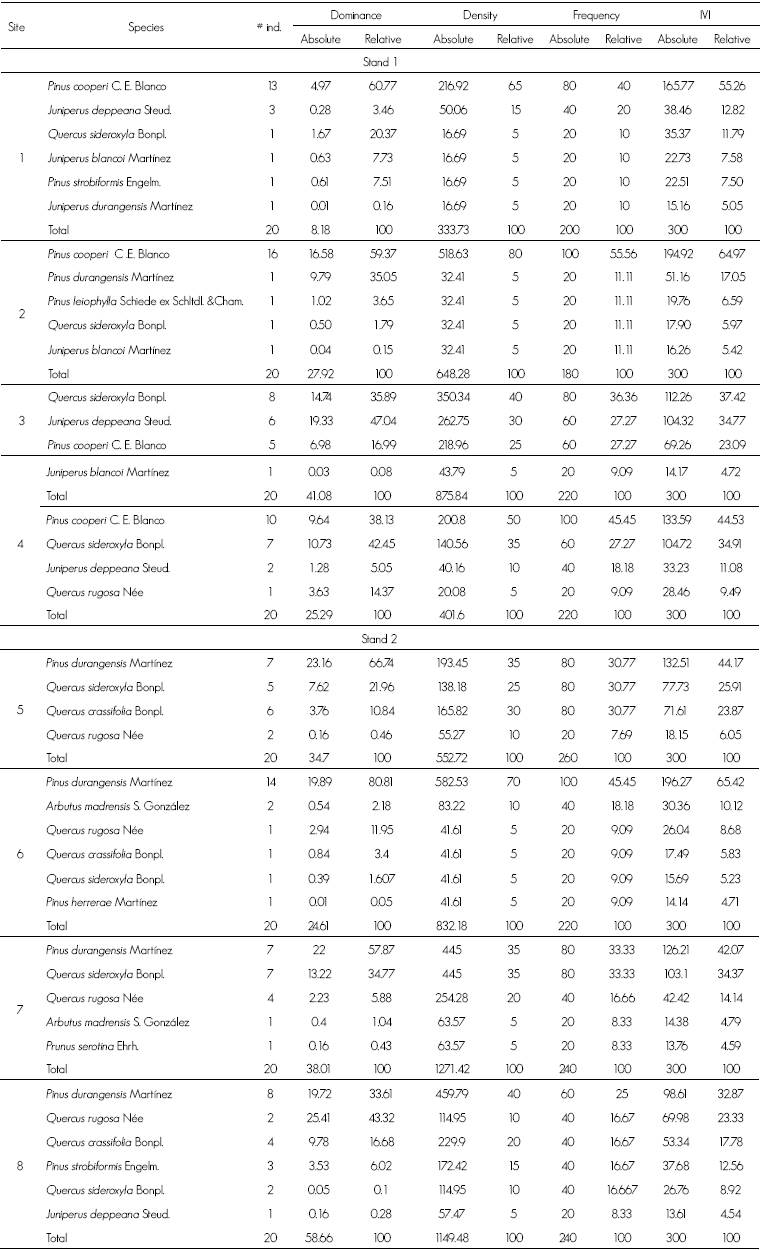

13 tree species belonging to five genera and five botanical families were identified (Table 1).

Table 1: Structural measures of the tree species by site.

# ind = Number of individuals; IVI = Importance Value Index.

In stand 1, the vegetation is dominated by Pinus cooperi C.E. Blanco; other tree species are Quercus sideroxyla Bonpl and junipers (Juniperus blancoi Martínez, J. deppeana Steud. and J. durangensis Martínez) (Table 1).

The relative value of the IVI evidences the composition of most sites of stand 1 in terms of the number of sampled trees and of the surface area they cover in relation to the baseline area; P. cooperi is the dominant floristic element. Besides, the largest population of Juniperus blancoi Martínez var. blancoi hitherto known to exist within the WSM was registered in this stand. This taxon grows locally to a height of 1 to 6 m and is dominant in the undergrowth of P. cooperi, Juniperus blancoi is a conifer with restricted distribution (Adams et al., 2006; Mastretta et al., 2011), and therefore its presence in Coscomate increases the biological value of the region.

In stand 2, the species with the highest importance value is Pinus durangensis, although the presence of arbutus (Arbutus madrensis S. González), wild black cherry (Prunus serotine Ehrb.) and various oak species (Quercus crassifolia Bonpl., Q. rugose Née, Q. sideroxyla Bonpl.) is also prominent; at genus level, Quercus species are predominant in the sites, with the exception of Site 6 (Table 1).

The existence of Pinus herrerae Martínez in stand 2 is indicative of a warmer and more humid climate that is characteristic of the tropical Madrean zone of the Sierra (González et al., 2012, 2013), which extends westward across the ravines to Coscomate, thereby accounting for the higher diversity in this stand.

The calculated IVI indicates that the dominant species in both stands is Pinus spp., followed by Quercus in a lower proportion; however, due to generic dominances, pine-oak or oak-pine forests are located in the same stand, as documented in the Ecological Zoning of the State of Durango (Semarnat, 2007) for the temperate forests of the area.

The comparative study between adjoining stands allowed detection of variations in structure and composition occurring within the same ecosystem. Although in general a particular species of conifers or of Quercus can develop in various degrees of slope (Martínez et al., 2013), other taxa have preferences for certain topoforms. Pinus cooperi is especially distributed in intermountain valleys, lowlands and low slopes with a mild inclination and tends to be dominant; this situation prevails in stand 1, where it is dominant around meadows and fluvial terraces.

On the other hand, the occurrence of associations of several species, as in stand 2, is related to the larger number of microhabitats to be found in steeper slopes.

The consociation of Pinus cooperi and the association of Pinus durangensis with other Pinus and Quercus taxa are among the most representative vegetal compositions of the WSM in Durango and are similar to those recorded by Márquez and González (1998), Márquez et al. (1999), and González et al. (2007, 2012).

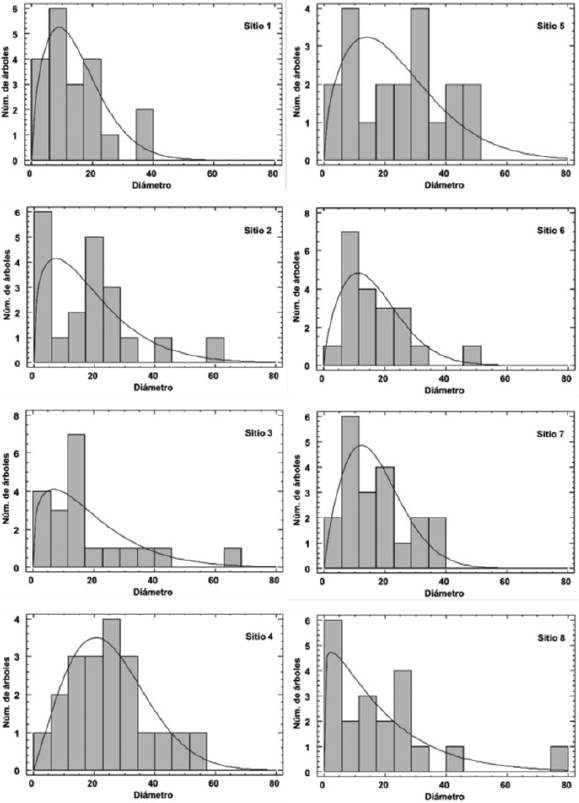

Diametric distributions indicate irregular masses in the forest of Coscomate, where there are both "inverted J" tendencies and curves in the mean apical diameters (Figure 3). However, the goodness-of-fit test showed that seven out of the eight sites adjust to the Weibull function (Table 2); this indicates a strong association between the observed and the expected diametric distributions, which allows setting goals for the future in regard to the health of the forest.

Table 2 Goodness-of-fit test for the Weibull function in the sampling sites.

* If the value of P is equal to or above 0.05, the idea that the data adjust to a Weibull distribution with a 95 % confidence interval cannot be ruled out.

Irregular distributions are particular to young forests, where trees with a diameter < 10 cm and an a mean diameter of 19.24 cm are predominant; these values are very similar to those cited by Návar and González (2009) for Durango, and by Návar (2010) for Nuevo León.

Although individuals with diameters above 40 cm are present, the structure of the sites shows a decrease in tree density as the diameter size increases, which reflects an adequate regeneration flow with a reserve of young individuals that will be able to replace those individuals with a larger diameter that may disappear in the future, thus ensuring the survival of the ecosystem.

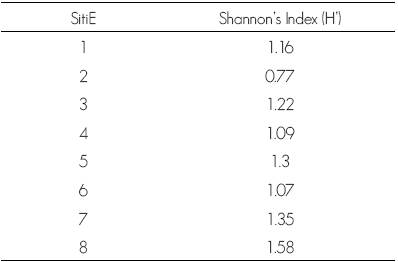

The results showed a high diversity value in the two studied stands, although this value is higher in stand 2. The Shannon-Wiener diversity index (H' = 0.77 to 1.58) (Table 3) is lower than that cited by González et al. (1993) for the La Michilía Reserve (0.98 to 2.26), but higher than the figures recorded by Návar and González (2009) for the Cielito Azul stand in San Dimas (0.53 to 1.33); however, the lower index in Cielito Azul was determined in sites with 100 % exploitation.

The larger diversity of stand 2 is related to climatic variables associated to a ravine with westward exposure that is part of this locality and where temperatures are less extreme, with a higher level of humidity coming from the Pacific Ocean.

Although the specific wealth of Site 1, located in stand 1, is similar to that of Sites 6 and 8 in stand 2 (six species in each), diversity differs between these sites, being low in Sites 1 and 6 because of the marked predominance of Pinus cooperi (Site 1) and P. duranguensis (Site 6), unlike in Site 8, where three species are observed to share similar structural characteristics.

The dendrogram resulting from the similarity matrix (Euclidean distance) (Figure 4) groups the sites in two differentiated sets corresponding to the studied stands. The greatest similarity was found to occur between sites 1 and 2 (stand 1) and between sites 5 and 8 (stand 2). The groupings are influenced by the number of individuals of the taxa with the highest important value index in the pairs of sites.

Conclusions

The diversity and structure of the compared forests in the Coscomate community reveal a marked difference in the vegetal composition and structure of two adjoining stands under similar conditions of altitude -an example of the ecological complexity found in the Western Sierra Madre. The diversity values compared to those of other regions of the WSM and the structural difference between the sites confirm the biological wealth of the region.

Knowledge of the diametric distribution function allows the forest managers to set goals in terms of the structure of the sites and, based on this, to effect removals without damaging the stability of the ecosystem.

The information generated in this study can become part of the management tools of the holders of this forest and contribute to optimize its management, as well as to the preservation of the biological wealth existing in it.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contribution by autor

David Alfredo Delgado Zamora: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and writing of the manuscript; Sergio Alonso Heynes Silerio: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and writing of the manuscript; María Daniela Mares Quiñones: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and writing of the manuscript; Norma Leticia Piedra Leandro: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and writing of the manuscript; Flor Isela Retana Rentería: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and writing of the manuscript; Karina Rodríguez Corral: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and writing of the manuscript Ali Ituriel Villanueva Hernández: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and writing of the manuscript; María del Socorro González Elizondo: field work, writing and correcting of the manuscript from its review; Lizeth Ruacho González: field work, analysis of diversity, calculation of importance value and of the diametric distributions, writing and correcting of the manuscript from its review.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the staff of the Coscomate ecotouristic center for their guidance during the course of this study, to the Instituto Politécnico Nacional for the support provided, and to J. G. González Gallegos and to two anonymous reviewers for their contributions for the improvement of the document.

REFERENCES

Adams, R. P., M. S. González E., M. González E. and E. Slinkman. 2006. DNA fingerprinting and terpenoid analysis of Juniperus blancoi var. huehuentensis (Cupressaceae), a new subalpine variety from Durango, Mexico. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 34: 205-21. [ Links ]

Cao, Q. V. 2004. Predicting parameters of a Weibull function for modeling diameter distribution. Forest Science 50: 682-685 [ Links ]

Challenger, A. y J. Soberón. 2008. Los ecosistemas terrestres. Soberón J., G. Halffter y J. Llorente-Bousquets. Capital natural de México: Conocimiento actual de la biodiversidad. Vol 1. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. México. pp. 87-108. http://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/pais/pdf/CapNatMex/Vol%20I/I03_ Losecosistemast.pdf (18 de marzo de 2014). [ Links ]

Colwell, R. K. 2006. EstimateS v. 8.2.0: Statistical estimation of species richness and shared species from samples. http://www.purl.oclc.org/estimates (22 de abril de 2014). [ Links ]

Corral R., S., J. G. Álvarez G., J. J. Corral R. and C. A. López S. 2015. Characterization of diameter structures of natural forests of northwest of Durango, Mexico. Revista Chapingo. Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 21 (2): 221-236. [ Links ]

Cottam, G. and J. T. Curtis. 1956. The use of distance measures in phytosociological sampling. Ecology 37 (3): 451-160. [ Links ]

González E., M. S., M. González E. y A. Cortés O. 1993. Vegetación de la Reserva de la Biosfera La Michilía, Durango, Mex. Acta Botánica Mexicana 22: 1-104. [ Links ]

González E., M. S. , M. González E. y M. A. Márquez L. 2007. Vegetación y ecorregiones de Durango. Plaza y Valdés Editores-Instituto Politécnico Nacional. México, D. F., México. 219 p. [ Links ]

González E., M. S. , M. González E., J. A. Tena F., L. Ruacho G. e I. L. López E. 2012. Vegetación de la Sierra Madre Occidental, México: Una síntesis. Acta Botánica Mexicana 100: 351-403. [ Links ]

González E., M. S. , M. González E., L. Ruacho G., I. L. López E., F. I. Retana R. and J. A. Tena F. 2013. Ecosystems and diversity of the Sierra Madre Occidental. : Gottfried G. J., P. F. Ffolliott, B. S. Gebow and L. G. Eskew (eds.). Merging science and management in a rapidly changing world: biodiversity and management of the Madrean Archipelago III. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Fort Collins, CO, USA. pp. 204-21. [ Links ]

Hammer, Ø., D. A. T. Harper and P. D. Ryan. 2001. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4(1): 1-9. http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm (27 de junio de 2014). [ Links ]

Magurran, A. E. 1988. Ecological diversity and its measurement. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ, USA. 179 p. [ Links ]

Márquez L., M. A. y M. S. González E. 1998. Composición y estructura del estrato arbóreo de un bosque de pino-encino en Durango, México. Agrociencia 32 (4): 413-419. [ Links ]

Márquez L., M. A. , M. S. González E. y R. Álvarez Z. 1999. Componentes de la diversidad arbórea en bosques de pino encino de Durango, México. Madera y Bosques 5 (2): 67-78. [ Links ]

Martínez A., P., C. Wehenkel, J. C. Hernández D., M. González E., J. J. Corral R. and A. Pinedo A. 2013. Effect of climate and physiography on the density of tree and shrub species in Northwest Mexico. Polish Journal of Ecology 61 (2): 295-307. [ Links ]

Mastretta Y., A., A. Wegier, A. Vázquez L. and D. Piñeiro. 2011. Distinctiveness, rarity and conservation in a subtropical highland conifer. Conservation Genetics. DOI: 10.1007/s10592-01-0277-y. [ Links ]

Mitchell, K. 2007. Quantitative analysis by the point-centered quarter method. Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Geneva, NY, USA. 56 p. http://arxiv.org/pdf/1010.3303.pdf (15 de agosto de 2013). [ Links ]

Moreno, C. 2001. Métodos para medir la biodiversidad. M&T -SEA. Vol. 1. Zaragoza, España. 84 p. [ Links ]

Návar C., J. J. 2010. Los bosques templados del estado de Nuevo León: el manejo sustentable para bienes y servicios ambientales. Madera y Bosques 16: 51-69. [ Links ]

Návar C., J. J. y M. S. González E. 2009. Diversidad, estructura y productividad de bosques templados de Durango, México. Polibotánica 27: 71-87. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 2006. Vegetación de México. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. México, D. F., México. http://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/publicaciones/librosDig/pdf/VegetacionMx_Cont.pdf (20 de abril de 2014). [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2007. Ordenamiento Ecológico del Estado de Durango. Gobierno del Estado de Durango-Semarnat. Durango, Dgo., México. 194 p. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (SEMARNAT). 2012. Bosques. http://www.semarnat.gob.mx/archivosanteriores/galeria/Documents/seccion/ecosistemas/Bosque/bosque.html (22 de abril de 2014). [ Links ]

Uribe, G. A. 1984. Comportamiento de las distribuciones diamétricas de frecuencias de bosques disetáneos. Seminario forestal, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Medellín, Colombia. 90 p. [ Links ]

Villarreal, H., M. Álvarez, S. Córdoba, F. Escobar, G. Fagua, F. Gast, H. Mendoza, M. Ospina y A. M. Umaña. 2006. Manual de métodos para el desarrollo de inventarios de biodiversidad. Instituto de investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt. Bogotá, Colombia. 236 p. [ Links ]

Wehenkel, C., J. J. Corral R. and K. von Gadow. 2014. Quantifying differences between ecosystems with particular reference to selection forests in Durango/Mexico. Forest Ecology and Management 316: 17-124. [ Links ]

Wright, S. J., H. C. Muller L., R., Condit and S. P. Hubbell. 2003. Gap-dependent recruitment, realized vital rates and size distributions of tropical trees. Ecology 84 (12): 3174-3178. [ Links ]

Received: September 23, 2015; Accepted: December 21, 2015

texto en

texto en