Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versión impresa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.7 no.33 México ene./feb. 2016

Articles

Relationship between bird communities and dendrometric variables in Pinus caribaea Morelet var. caribaea W. H. Barret et Golfari plantations in Viñales , Cuba

1Departamento Forestal, Facultad de Forestal y Agronomía, Universidad de Pinar del Río, Cuba. Correo-e: sabp@upr.edu.cu

2Delegación Municipal de la Agricultura, San Luís, Pinar del Río, Cuba.

3Centro de Estudios Forestales, Facultad de Forestal y Agronomía, Universidad de Pinar del Río, Cuba.

The association observed between the bird communities and Pinus caribaea var. caribaea plantations leads to expect a correlation with the characteristics of the trees. This gave rise to the study described below with the purpose of evaluating the existing relationship between the height, tree density and the basal area and bird communities. The sampling was carried out in January through May, 2015, using 30 fixed points in circular plots of 25 m of radius for the forestry study. The abundance and richness between plots and months was compared using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric range comparison test; Spearman's Rho non-parametric correlation matrix was utilized for the correlation between this last condition and the dasometric variables, and the link between these and the makeup of the species was determined through a canonical correspondence analysis. 41 species of birds belonging to 16 families and 9 orders were detected; of these, the best represented were the order of Passeriformes and the Parulidae family. In the vertical stratification of the vegetation, the middle stratum was the most visited (42 %). The birds were grouped in 21 trophic groups, among which foliage gleaning insectivores stand out, with 12.1 % of the total. A direct relationship is concluded to exist between the richness and abundance of birds and tree density and the basal area, and, to a lesser extent, the tree height average.

Keywords: Height; basal area; Cuba; tree density; Passeriformes; Pinus caribaea Morelet. var. caribaea W.H. Barret et Golfari

A partir de la asociación observada de las comunidades de aves con las plantaciones de Pinus caribaea var. caribaea se espera alguna vinculación con las características del arbolado; así, se planteó el estudio que se describe a continuación con el objetivo de evaluar la relación existente entre la altura, la densidad y el área basal y las comunidades de aves. El muestreo se llevó acabo de enero a mayo de 2015 mediante 30 puntos fijos en parcelas circulares de 25 m de radio para el estudio forestal. Para comparar la abundancia y la riqueza entre parcelas y meses se utilizó la prueba no paramétrica de comparación de rangos de Kruskal Wallis; para la correlación entre esta última condición y las variables dasométricas se trabajó con la matríz de correlaciones no paramétricas de Rho Spearman y para determinar la vinculación de las mismas con la composición de las especies se realizó un análisis de correspondencia canónico. Se detectaron 41 especies de aves pertenecientes a 16 familias y nueve órdenes, de los cuales sobresalen el de los Paseriformes y la familia Parulidae. En la estratificación vertical de la vegetación, el estrato medio fue el más visitado (42 %). Se agruparon en 21 grupos tróficos, entre los que sobresalieron los insectívoros de follaje por espigueo, con 12.1 % del total. Se concluye que existe relación directa de la riqueza y abundancia de las aves con la densidad y el área basal, y en menor proporción con la altura promedio de los árboles.

Palabras clave: Altura; área basal; Cuba; densidad de árboles; Paseriformes; Pinus caribaea Morelet var. caribaea W.H. Barret et Golfari

Introduction

Pinus caribaea Morelet var. caribaea W. H. Barret et Golfari plantations are the surface areas which best represent the forest richness in the province of Pinar del Río, where forest management and exploitation have an impact on biodiversity; birds, particularly, are the most numerous group of vertebrates both in the natural forests and in the plantations.

There have been few faunal studies carried out in the Viñales National Park based on the relationship between the fauna and the vegetation; however, since the XIXth century, this place has drawn the attention of both foreign and national naturalists because of its great richness and variety of species (Corvea et al., 2014).

371 wild species belonging to 208 genera, 63 families and 21 orders have been registered in Cuba. The terrestrial species add up to 217; 69 are associated with fresh waters, and 83 with sea waters; of these, 28 are endemic and amount to 13.1% of all Cuban bird life (Garrido and Kirkconnell, 2011).

Several researchers have studied the communities of birds that live in the pine forest ecosystems in different regions; Vicente (1991)) studied the structure of 10 bird life-vegetation systems of three pine woods; López and Moro (1997) studied the birds in Pinus halapensis Miller plantation in southeastern Spain in relation to the makeup and structure of the vegetation; Canterbury et al. (2000) developed and evaluated environmental indicators at community level, as well as the habitat associated to the birds, in 197 quadrants in pine forests from Georgia to Virginia (United States of America) with the representation of a gradient in anthropogenic disturbance levels.

Although this forest association constitutes a large portion of the vegetation of the Caribbean, little work has been done in regard to its bird life (O'Brien, 2005). A pioneering work was performed by Cruz (1988), who studied the use of the resource for the bird species in a Pinus caribaea Morelet plantation in Puerto Rico and recommended the maintenance of a diverse undergrowth and of the native trees in order to improve their habitats.

Within this context, several researches have been carried out in the pine forests of Cuba. Huerta et al. (1984) performed 13 counts of these animals with the purpose of determining the abundance of each species, as well as their diversity in this forest association of white savannahs in the Isla de la Juventud.

García et al. (1989) quantified on 24 occasions the existences of birds between March 7 and 15, 1988, in La Zoilita, Sierra de Cristal. The relative abundance for pine forests was of 54.3 individuals ha-1, whereas in sites occupied by vegetation of a high ecological variability, it was of 70 specimens ha-1. Hernández et al. (1998) carried out a study of the structure of bird communities that live in 216 has of a 25 year-old Pinus caribaea forest, applying the Census Itinerary method. They detected 28 species, of which 22 (78.5 %) were permanent residents, and 6 (21.4 %) were migratory; they grouped them in 17 trophic guilds; of the permanent resident species, 5 (22.7 %) are endemic, and 9 (40.9 %) are considered endemic at a subspecific level.

In 34 sampling areas of 10 localities in Cuba, González et al. (1999) used the linear transect, counting plots, and capture with ornithological nets to evaluate the terrestrial bird communities. They evaluated the structure and makeup of the vegetal formations using the vegetation plot method; according to their results, the structural variables that most influenced the arrangement of the habitats and the bird populations were canopy coverage, soil coverage and foliage volume.

Mereck (2004) carried out a research in five ecosystems (gallery forest, hillock semi-deciduous, hillock xerophile, pine and oak forests) in the San Andrés Valley, which belongs to the "La Palma" Integral Forest Enterprise; the point count without distance estimation method proposed by Wunderle (1994) was utilized for the Caribbean birds. A total of 50 bird species were identified, including specimens belonging to 10 orders and 63 families; eight are endemic at a specific level, and 13, at a subspecific level.

Peraza and Berovides (2007) studied the space-time dynamics of the abundance, diversity and uses of resources (substrata and vegetation strata) of two assemblages of birds in pine forests of the Managed Floristic Reserve San Ubaldo Sabanalamar, in Pinar del Río.

A potential association between the dendrometric characteristics and the bird species in Pinus caribaea in Cuba has not been studied so far. Therefore, the general objective of the study described below was to evaluate the relationship of birds with height, density, and basal area in a plantation of this species, and, specifically, to determine the functional groups (trophic guilds) and the abundance and diversity of the birds.

Materials and Methods

The study area is located in the Viñales National Park (PNV), in the municipality of Viñales, in the Pinar del Río Province; it covers 1 510 ha, of which 1 120 belong to the core areas, and 3 890 ha to the buffer zone, located in the east-central portion of Sierra de los Órganos. It stretches from the NE to the SW, with a maximum width of 8 km and a minimum width of 2.5 km, and covers a total of 15 010 ha, not counting the 920 ha belonging to the adjacent keys, which represent 6 % of the total surface area of the Province.

The research was carried out in a Pinus caribaea plantation in the locality of Moncada, 23 km away from the town of Viñales, on elevations where the predominant vegetation is pine, which grows on very poor, eroded soils (Figure 1).

The temperature regime ranges from 22 °C to 24 °C (mean temperature in the winter) and from 25 °C to 27 °C (mean temperature in the summer). The average accumulated precipitation is 1 600 to 1 800 mm year-1. The mean annual relative humidity ranges between 90 and 95 % (07:00 h) and 65-70 % (13:00 h).

The bird inventory was carried out using the fixed-radius circular plots method; 30 count points with a fixed diameter of 25 m and separated by a distance of 150 m were determined, with 10 min observation periods (Hutto et al., 1986) in the first hours of the morning, between 07:30 and 1:30 AM from January to May, 2015. The birds registered in the census were grouped by orders and families according to the criteria of Llanes et al. (2002), and classified by trophic groups according to the criteria of Kirconnell et al. (1992).

The vegetation was sampled in April and May, in the same plots utilized for the bird census, in order to determine the relationship between the variables of the vegetation and of the detected birds.

The estimated structural parameters of the vegetation were:

Tree density (td = trees/ha) = Number of individuals per tree species by phenologic status

Diameter of the trees at a height of 1.30 m (DBH m) = all the trees were ranged by diameter class

Tree canopy height (m) = average height (m) of the trees in the plot

Species abundance and richness were compared between plots and between months, using the Kruskal-Wallis non-parametric range comparison test. The correlation between the richness of species and the dendrometric variables was determined using Spearman's Rho non-parametric correlation matrix. In order to identify the incidence of the dendrometric variables on the makeup of ornithological species, canonical correspondence analysis was carried out, using the SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions) statistical package, version 15.0.

Results and Discussion

A total of 41 bird species, grouped in 9 orders and 16 families, were counted. The largest number of observed species was 35, in January, and the smallest number was 27, in May.

There is a significant difference in richness in the comparisons between months (Table 1) due to the fact that the study was carried out during the periods of winter and spring between January and May: the results coincide with the findings of Pérez (2003 and 2007) in researchers performed in the Guanahacabibes peninsula; with those of Mereck (2004), in the La Palma Integral Forest Enterprise (EFI), and with those of Alonso (2009), in EFI Minas de Matahambre.

Table 1 Result of the Kruskal-Wallis test for the comparison between months and between abundance (A) and richness (W).

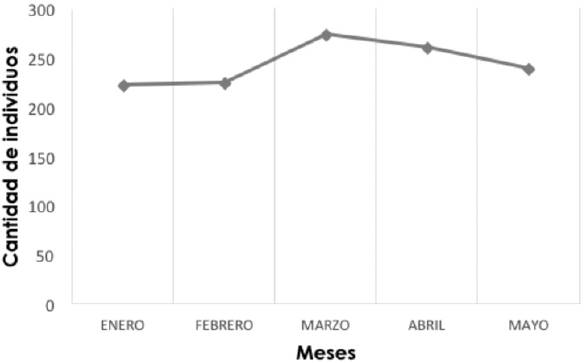

The lowest sighting rates occurred in the months of January and February, with 222 and 224 individuals, respectively, and the highest, in March and April, with 273 and 261, when many bird species were observed during courting and mating; in May, several nests were located in the area (Figure 2).

The order of Passeriformes comprises 50 % of the total of the present families, of which the best represented were Parulidae with 19.5 %, Columbidae, with 14.6 %, and Tyranidae, with 9.7 %. The results were compared with those obtained in the studies by Pérez et al. (2003); Mereck (2004); Toledo (2004); Pérez (2007); Peraza (2008) and Alonso (2009).

The species were grouped in 21 trophic guilds, adding up to 62 % of the species registered by Kirkconnell et al. (1992); foliage- gleaning insectivores prevail, with 12.1 %, and soil granivores with 9.7 %. Acosta and Múgica (1988) obtained similar results in eight arboreal formations in the national territory, and Sánchez (2007), in natural Pinus tropicalis Morelet forests (Figure 3).

(ITE) = Tree trunk gleaning insectivore; (IFE) = Foliage gleaning insectivore; (ITFE) = Tree trunk and foliage gleaning insectivore; (N-IVC) = Nectarivore-insectivore with hovering flight; (ISFPE) = Ground and foliage gleaning and pecking insectivore; (I-FP) = Insectivorous-fruitarian perching bird; (IPT) = Tree-trunk boring insectivore; (GS) = Ground grain eater; (F) = Fruitarian; (GSF) = Ground and foliage grain eater; (DIPV) = Predator of insects and small vertebrates; (IPRP) = Perching insectivore with hovering and chasing; (IP) = Perching insectivore; (IPVC) = Perching insectivore with hanging flight; (F-G) = Fruitarian-grain eater; (I-FPE) = Gleaning and pecking insectivore-fruitarian; (I ) = Insectivore; (ISPT) = Insectivore (I-FSR).

Figure 3 Representation of the percentage of species per trophic groups present in the study area.

Figure 4 shows the average behavior of the species abundance and richness by plot during the study period; plot 1 had the highest values, which may be accounted for by the lower density of pine trees and the existence of a larger number of other tree species, like Abarema obovalis (A. Rich.) Barneby & J. W. Grimes, which were in bloom and are attractive to insects, Davilla rugosa Poir, and species of the Melastomataceae family that were fruiting.

Plots 8 to 12 had the lowest values for abundance and richness, which may be due to higher density of trees of a lower height, with an herbaceous undergrowth essentially constituted by two fern species (Odontosoria sp. and Urechites luteus (L.) Britton) that do not bear fruits and on which birds were rarely ever sighted.

Conversely, species abundance and richness had a good behavior in plots 13 to 23, much in the same manner as in plot 1, but in this case also due to the low tree density with a large number of vegetal species in the undergrowth, including Byrsonima coriacea (Sw.) DC., Quercus cubana A. Rich., Clidemia strigillosa (Sw.) DC., Conostegia xalapensis (Bonpl.) D. Don ex DC., Miconia laevigata (L.) D. Don, Matayba oppositifolia (A. Rich.) Britton., Clusia rosea Jacq. and Gouania polígama (Jacq.) Urb., which are a source of food for the birds.

In the contrast statistics, comparison shows significant differences in species abundance and richness between plots; these may be determined by the tree density, the average height of the plots and the abundance of vegetal species (Table 2). The results coincide with those obtained by Peraza (2008).

Table 2 Results of the Kruskal-Wallis test for the comparison between plots and for abundance (A) and richness (W).

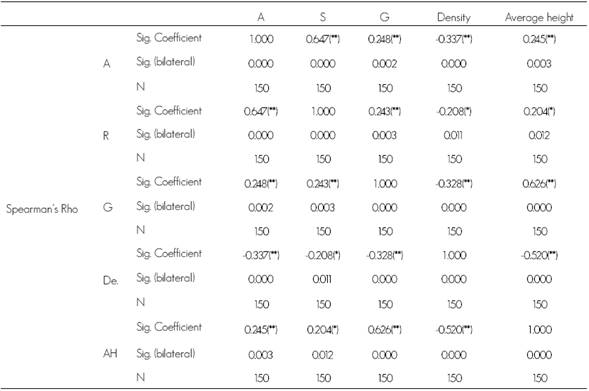

Table 3 shows a low correlation between the basal area and the abundance and richness of bird species; however, this correlation is significant, with a 99 % confidence interval, which may be influenced by the height/basal area mathematical ratio and by the fact that many bird species are distributed among the higher strata of the trees at different times of the year, like Tyrannus caudifaciatus d'Orbigny, 1839 and Turdus plumbeus Linnaeus, 1758, although many forage on the ground.

Table 3 Representation of Spearman's Rho non-parametric correlation matrix.

** The correlation is significantiva at level 0.01 (bilateral); * The correlation is significantive at level 0.05 (bilateral); G = Basal area; De = Density; AH = Average height of the plot; S = Richness and A = Abundance.

On the other hand, tree density shows a low inverse correlation with species abundance and richness, which may be accounted for by the bird species that require a lower tree density and a larger space in which to fly and search for food. The average height has a positive correlation with species abundance and richness and may be determined by certain bird species that obtain their food from tall trees, such as the representatives of the trophic guilds of tree-trunk and foliage gleaning insectivores and other insectivores.

Figure 5 shows a better association between the density variable and the birds in quadrant 2, with the following species: Mniotilta varia Linnaeus, 1766 (bij trepa), Teretistris fernandinae Lembeye, 1850 (chillina), Cyanerpes cyaneus Linnaeus, 1766 (aparecid), Chlorostilbon ricordii Gervais, 1835 (zunzún), Setophaga palmarum J. F. Gmelin, 1789 (bij común), Tyrannus dominicensis J. F. Gmelin, 1788 (pitirre) and Myiarchus sagrae Gundlach, 1852 (bobito); in the particular case of the last two, this result may be attributed to the manner of their flight, which requires more space to capture food resources, while the others require a higher density in order to be able to capture insects.

Figure 5 Representation of the arrangement chart of the correspondence analysis of bird species with the density, height and basal area in a Pinus caribaea Morelet plantation.

In quadrant 3, the bird species associated with the basal area and the height are Spindalis zena Linnaeus, 1758 (cabrero), Setophaga pityophila Gundlach, 1858 (biji pinar), Mniotilta varia, (bij trepa) Priotelus temnurus Temminck, 1825 (tococoro), Melanerpes superciliaris Temminck, 1827 (carpi ja) and Xiphidiopicus percussus Temminck, 1826 (carpi ve). The studied species that showed an association were mostly insectivorous.

Conclusions

The taxonomic makeup of the bird communities associated to the study area consisted of 9 orders, 16 families and 41 species. The order of Passeriformes and the Parulidae family were the best represented. The most abundant trophic guilds were foliage gleaning insectivores, with 12.1 %, and ground grain eaters, with 9.7 %. The birds have more relation to tree density and basal area, and less association with the average height of the trees.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Contribution by author

Sael Anoi Báez Pérez: field work, data collection on the plots and count points, bird monitoring, and vegetation study, data processing, analysis of the results, and drafting of the document; Leyanis Pintado Martínez: field work, data collection on the plots and count points, bird monitoring, vegetation study and characterization of the study area; Fernando Hernández Martínez: field work, data collection on the plots and count points, bird monitoring, vegetation study, and taxonomic classification of the bird species.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the technicians and managers of the Viñales National Park for their support with the transportation to the study area, and to MSc. C. Yatsunaris Alonso Torrens to Dr. C. Alina for their help with the field work.

REFERENCES

Acosta, C. M. y L. Mugica. 1988. Estructura de las comunidades de aves que habitan en los bosques cubanos. Universidad de La Habana. Facultad de Biología. La Habana, Cuba. pp. 9-19. [ Links ]

Alonso Y. (2009) Estructura y composición de las comunidades de aves asociadas a pinares de la EFI "Minas de Matahambre". Tesis en opción al título académico de Máster en Ciencias Forestales, Universidad de Pinar del Rio, Cuba. [ Links ]

Canterbury, G. E, T. E. Martin, D. R. Petit, L. J. Petit and D. F. Bradford. 2000. Birdcommunities and habitat as ecological indicators of forest condition in regional monitoring. Conservation Biology 14 (2): 544-558. [ Links ]

Corvea, J. L., R Novo y M. E. Palacio. 2014. Plan de Manejo del Parque Nacional Viñales. Ministerio de Ciencia Tecnología y Medio Ambiente. Centro de Investigaciones y Servicios Ambientales (ECOVIDA). Pinar del Río, Cuba. pp. 3-12. [ Links ]

Cruz, A. 1988. Avian resource use in a Caribbean pine plantation. Journal of Wildlife Management 52: 274-279. [ Links ]

García, M .E., J. De la Cruz y A. Ramos. 1989. Algunos aspectos ecológicos de la ornitofauna de "La Zoilita", Sierra de Cristal. Garciana 16: 1-2. [ Links ]

Garrido, O. H. y A. Kirkconnell. 2011. Aves de Cuba: Guía de Campo / Field Guide to the Birds of Cuba. Spanish-Language Edition. Cornell University Press. Ithaca, NY, USA. pp. 1-3. [ Links ]

González, H., A. Llanes, B. Sánchez, D. Rodríguez, E. Pérez, P. Blanco, R. Oviedo y A. Pérez. 1999. Estado de las comunidades de aves residentes y migratorias en ecosistemas cubanos en relación con el impacto provocado por los cambios globales. Programa Nacional de Cambios Globales. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática. La Habana, Cuba. 118 p. [ Links ]

Hernández, F., G. Padrón, J. Mandeck, Y. Camero y D. Blanco. 1998. Estructura y composición de las comunidades de aves que habitan en un bosque de pinos (Pinus caribaea Morelet). Ra Ximhai 4 (2): 215-233. [ Links ]

Huerta, T., V Berovides y B. Sánchez . 1984. Comunidad de aves de las sabanas arenosas de la Isla de la Juventud. In: Memorias de la IV Conferencia Científica sobre Educación Superior. Universidad de La Habana, Cuba. pp. 457-473. [ Links ]

Hutto, R. L., S. M. P. Letschet and P. Hendricks 1986. A fixed-radius point count methods for nonbreeding and breeding season use. Auk (103): 593-602. [ Links ]

Kirkconnell, A., O. H. Garrido, R. M. Posada y S. O. Cubillas. 1992. Los grupos tróficos en la avifauna Cubana. Poeyana 435:1-21. [ Links ]

López, G and M. J. Moro. 1997. Birds of Aleppo pine plantations in southeast Spain in relation to vegetation composition and structure. Journal of Applied Ecology 34 (5):1257-1272. [ Links ]

Llanes, A., H. González, E. Pérez y B. Sánchez . 2002. Lista de las aves registradas para Cuba. Aves de Cuba. Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática. UPC Print. Vaasa, Finlandia. pp. 147-155. [ Links ]

Mereck, T 2004. Estado actual de la avifauna asociada a ecosistemas de montaña de la EFI La Palma con fines de conservación. Tesis en opción al título académico de Máster en Ciencias Forestales. Universidad de Pinar del Río. Pinar del Río, Cuba. pp. 37-48. [ Links ]

O'Brien, J. 2005. Caribbean boats large areas of fire-dependent natural pine forest. SRS-4104 Science High Lights. Miami, FL, USA. 1 p. [ Links ]

Peraza, E. 2008. Dinámica de la abundancia, diversidad y uso de recursos, en un ensamblaje de aves de bosque de pinos con diferentes historias de manejo, en la Reserva Florística Manejada San Ubaldo Sabanalamar Pinar del Río. Tesis de Master en Ciencias. Universidad de Pinar del Río. Pinar del Río, Cuba. pp. 36-48. [ Links ]

Peraza, E. y V. Berovides, 2007. Dinámica de Índices ecológicos en una comunidad de aves de Pinares en la reserva florística manejada San Ubaldo- Sabanalamar. Cubazoo 16:25-30. [ Links ]

Pérez, F. Delgado F. y A. Tamarit L. 2003. Comunidades de aves de bosque semideciduo en la Reserva de la Biosfera Península de Guanahacabibes, Cuba. Crónica Forestal y del Medio Ambiente 18: 25-37. [ Links ]

Pérez, H. A. 2007. Ecología de las comunidades de aves de bosque semideciduo de Reserva de la Biosfera Península de Guanahacabibes en diferentes momentos de recuperación después de un aprovechamiento forestar. Tesis en opción al título académico de Doctor en Ciencias. Universidad de Alicante. Alicante, España. pp. 46-88. [ Links ]

Toledo, R 2004. Grado de antropización y manejo forestal en relación con la diversidad y abundancia de las comunidades de aves en la cuenca del Río Cuyaguateje. Tesis de Master en Ciencias. Universidad de Pinar del Río. Pinar del Río, Cuba. pp. 39-73. [ Links ]

Vicente, A. M. 1991 Algunos aspectos sinecológicos de los sistemas avifaunavegetación. Caso de un gradiente estructural simplificado. Orsis 6: 167-190. [ Links ]

Wunderle, J. M. Jr. , 1994. Métodos para contar aves terrestres del Caribe. U. S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. Gen. Tech. Rep. S0-100. New Orleans, LA, USA. 28 p. [ Links ]

Received: October 12, 2015; Accepted: December 19, 2015

texto en

texto en