Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias forestales

versão impressa ISSN 2007-1132

Rev. mex. de cienc. forestales vol.6 no.32 México Nov./Dez. 2015

Article

Changes in the microphyll desert scrubland vegetation in an area under management

1 Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, Facultad de Ciencias Forestales.

2 Cemex-Naturaleza Sin Fronteras, A.C., Proyecto El Carmen.

The aim of this study was to assess changes in the structure and floristic composition of the microphyll desert scrubland from the application of a technique of ecological restoration and the occurrence of natural fires in different periods in the Chihuahuan Desert. Through five treatments (control (MDMt), aerator roller applied in 2004 (RA04), 2008 (RA08), 2011 (RA11) and burned area in 2011 (IN11)), diversity and similarity between species were determined by Shannon and Sørensen indices as well as their importance value index (IVI). 28 tree and shrub species belonging to 14 families, among which Asteraceae, Fabaceae and Cactaceae noted for their abundance were recorded. The Shannon index revealed a higher richness (H'= 2.103) in the RA11 treatment while in the IN11, the shortest (H' = 1.21). The greatest similarity was verified between treatments RA04 and RA08 76 % and otherwise between RA11 and RA08 with 44 % according to the Sørensen index. The Kruskal-Wallis test showed no significant difference between treatments respect to IVI (F = 2.463, df = 4, P = 0.261). The aerator roller treatment increased species richness at a short-term and dominance decreased substantially in Cactaceae and Agavaceae species, and favored Larrea tridentata coverage. The heat treatment reduced the coverage of the latter, of Jatropha dioica , Opuntia engelmannii and encouraged the presence and coverage of Viguiera stenoloba , Condalia spathulata and Ziziphus obstusifolia .

Key words: Chihuahuan Desert; diversity index; similarity index; microphyll desert scrubland; aerator roller; rehabilitation

El objetivo de este estudio consistió en evaluar los cambios en la estructura y composición florística del matorral desértico micrófilo a partir de la aplicación de una técnica de restauración ecológica y la ocurrencia de incendios naturales en diferentes periodos en el Desierto Chihuahuense. Mediante cinco tratamientos (testigo (MDMt), rodillo aireador aplicado en 2004 (RA04), en 2008 (RA08), en 2011 (RA11) y área incendiada del 2011 (IN11)) se determinaron la diversidad y la similitud entre especies con los índices de Shannon y Sørensen , así como su índice de valor de importancia (IVI). Se registraron 28 especies arbóreas y arbustivas pertenecientes a 14 familias. Asteraceae, Cactaceae y Fabaceae destacaron por su abundancia. El índice de Shannon reveló una mayor riqueza (H' = 2.103) en el tratamiento RA11 mientras que el IN11, el menor (H' = 1.21). La máxima similitud se verificó entre los tratamientos RA04 y RA08 con 76 % y lo contrario entre RA11 y RA08 con 44 % de acuerdo al índice de Sørensen . La Prueba de Kruskall-Wallis mostró que no hay diferencia significativa entre tratamientos respecto al IVI (F= 2.463, G.L. = 4, P = 0.261). El tratamiento de rodillo aireador incrementó, a corto plazo, la riqueza de especies y disminuyó substancialmente la dominancia de especies de Cactaceae y Agavaceae, y favoreció la cobertura de Larrea tridentata . El tratamiento de fuego redujo la cobertura de esta última, además de la de Jatropha dioica , Opuntia engelmannii y estimuló la presencia y cobertura de Viguiera stenoloba , Condalia spathulata y Ziziphus obstusifolia .

Palabras clave: Desierto Chihuahuense; índice de diversidad; índice de similitud; matorral desértico micrófilo; rodillo aireador; técnicas de rehabilitación

Introduction

The Chihuahuan Desert is located at the north of Mexico, and it is the largest in North America, with an area of 507 000 km2 (Hernández et al., 2007); 85 % of the total lies within Mexican territory and 15 % in the United States of America (Brooks and Pyke, 2001). It is the second most biologically diverse desert in the world (Hoyt, 2002) in which 329 species of cacti have been recorded (Esqueda et al., 2012) and gathers a high level of endemism (Rzedowski, 2006). It comprises three basic types of vegetation: microphyll desert scrubland, rosetophilous desert scrubland and crasicaule desert scrubland (Rzedowski, 1978) as well as other plant communities recognized as halophytic vegetation and gipsophylic pasture (Villarreal and Valdés, 1992-1993).

The biotic resources of the place have been under pressure in the last 100 years due to anthropogenic activities (Challenger, 1998; Cervantes, 2005; Hernández et al., 2007; Challenger and Soberón, 2008) that have triggered problems of deforestation, erosion and decreased in quality and size of the habitat for wildlife species (INE-Semarnat, 1997). To this, forest fires which affected 317 000 ha in the region during 2011 (Semarnat, 2012) must be added.

The microphyll desert scrubland covers an area of 20 879 927 ha and in the state of Coahuila, it comprises 3 066 492 ha (Inegi, 2014). Most of the studies in this plant unit have focused on the study of the effect of fragmentation on wildlife populations (Menke, 2003; Tinajero and Rodríguez, 2012; Boeing et al., 2013) and other more specific on the biocides and antifungal properties of Larrea tridentata (Sesse & Moc. ex DC.) Coville, its phytosociology and its potential use for the disinfection of soil (Ledezma, 2001; Juárez, 2002; Lira, 2003; Díaz et al., 2008; Peñuelas et al., 2011). However, few studies have evaluated the structure and species composition of this community, which would act as a useful indicator for the assessment and conservation of natural resources in the region.

The objective of this research was to assess the changes generated in the structure and floristic composition of the microphyll desert scrubland due to ecological restoration techniques such as the aerator roller and natural fires in different periods. The hypothesis is that the mechanical treatment applied at different times modified the structure and floristic composition of this type of vegetation and increased biodiversity.

Materials and Methods

The research was conducted at the Unidad para la Conservación, Manejo y Aprovechamiento Sustentable de la Vida Silvestre (UMA) (Unit for the Conservation, Management and Sustainable Utilization of Wildlife (UMA) known as "Pilares", adjacent to the Maderas del Carmen Reserve, located in Ocampo, Muzquiz and Acuña Coahuila state municipalities (Figure 1).

This place is found between 29°22.45' and 28°42.21' N; 102°56.23' and 102°21.08' W, at an altitude of 1 182 m. The annual average rainfall is 237.4 mm and the annual average temperature is 21.5 °C. According to climate data from the INIFAP's Pilares station during the period of 2011-2013 the average rainfall was only 65 mm, confirming the occurrence of an extremely dry period in the area.

The predominant soils are of the Calcium castanozem, Rendzina, Chromic vertisol, Lithosol and Regosol calcaric type (SPP, 1982a; SPP, 1982b; SPP, 1983). The vegetation types are represented by oak (Quercus), pine (Pinus) and fir (Abies) forests; submontane scrub, grassland, Chihuahuan desert scrub and including microphyll and rosetophilous scrubs, gypsum and halophytes communities (INE-Semarnat, 1997). The experimental plots were located in the microphyll desert scrubland, whose length is 11 700 ha in the area (Inegi, 2014).

Larrea tridentata, Flourensia cernua DC., Parthenium incanum Kunth, Fouquieria splendens Engelm., Parthenium argentatum A. Gray, Ephedra torreyana S. Watson, Prosopis glandulosa Torr. are outstanding from their density in this type of vegetation (Alanís et al, 1996).

The roller used in the practice of habitat improvement for wildlife on the plains of the sierra Maderas del Carmen is an 11 ton Lawson aerator assembled to a tractor. Roller blades are about 15 cm long, which when drilling the ground, form small channels; this instrument was implemented in the months after the rainy season of 2004, 2008 and 2011.

In the spring of 2014 five treatments in the areas under management of wildlife habitat in the microphyll desert scrubland were selected and sampled from the same soil type, calcaric Regosol; the treatments are: 1) Control (MDMt), 2) Aerator roller applied in 2004 (RA04), 3) Roller applied in 2008 (RA08), 4) Roller implemented in 2011 (RA11) and 5) Burned area in 2011 (IN11), which was the result of forest fires that occurred in Coahuila in the spring of 2011 (Conafor, 2011) and where the area under study contains 1 899 has of the vegetation type of interest affected by this phenomenon. There is not cattle grazing since 2000, and is exercised only by wildlife, for which there are not exclusion zones. To determine the structure and diversity of species, six plots (10 m x 10 m) at random in each treatment were georeferenced.

In each treatment mensuration measurements were performed on every tree and shrub; coverage of the cup was used to estimate the dominance, a suggested attribute when most taxa are shrubs with many stems and root diameters under d0.10 (Franco et al., 1989; Domínguez et al., 2013). In each plot the density was quantified by plant species, if at least 50 % of the structure was within it.

The ecological indicators, abundance (A), dominance (Y) frequency (F) and importance value (IVI) (Magurran, 2004) were estimated. Diversity and similarity were evaluated with standardized Shannon index (e) (Magurran, 2004; Sæther et al., 2013). This index describes how diverse may be a site, as it takes into account the number of species (richness) and of individuals in each one of them (Mostacedo and Frederiksen, 2000) and to determine whether there were significant differences in diversity between treatments, paired t test were used (Hutcheson, 1970; Magurran, 1988; Brower et al, 1998). To calculate the similarity between them, the Sørensen Index was applied (Magurran, 2004), which relates the number of shared species with the arithmetic mean of species in both sites (Villarreal et al, 2004).

Statistical analysis. For the calculation of the standardized Shannon (e) and Sørensen indexes, the MultiVariate Statistical Package (MVSP) 3.1 program was used (KCS, 2007). For the Diversity t test the Past 3.2 program (Hammer et al., 2001) was used. To test the assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances for the Importance Value Index (IVI), the data were subjected to statistical tests of Shapiro-Wilk (Steel and Torrie, 1980). As the results showed that most of the data were not normally distributed, the nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis (Ott, 1993) was used to detect significant differences between treatments with respect to IVI and the structure and diversity of species between treatments using the following indicators: coverage, average height and number of species; The statistical program used for this analysis was Statistix 8.1 (Analytical Software, 2003).

Results and Discussion

28 tree and shrub species belonging to 14 families were recorded. The highest species richness were Asteraceae, Fabaceae and Cactaceae, each with three taxa; families: Boraginaceae, Zygophyllaceae, Anacardiaceae, Rhamnaceae, Euphorbiaceae Agavaceae and are represented with two taxa each. Fouquieriaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Verbenaceae, Cannabaceae, Achatocarpaceae, Ephedraceae and Koeberliniaceae are only represented a taxon. Asteraceae, Fabaceae and Cactaceae, dominant in the different treatments are regularly associated with desert scrub communities (Estrada et al., 2005; González et al., 2010) and characterized by demanding little water and organic matter (Ordóñez, 2003; Espinoza and Návar, 2005; Alanís et al., 2008; Calle and Murgueitio, 2008; Landázuri and Tigrero, 2009; Amaya, 2009) (Table 1).

Table 1 Identified species and families present in the studied microphyll desert scrubland of the Chihuahuan Desert.

In the RA1 (17) and IN11 (16) treatments was recorded the greatest number of species as well as the smallest (7) in MDMt; in RA04 (11) and RA08 (10) a similar amount was counted. From the five treatments, in control (MDMt), the Shannon's diversity index (1.484) was close to the RA08 treatment (1.480) (Table 2); in spite of the difference in the number of species, these results might be explained as the changes in richness are balanced with those of abundance.

Table 2 Shannon's diversity index and number of species by treatment.

MDMt = Control; RA04 = 2004 aerator roller; RA08 = 2008 aerator roller; RA11 = 2011 aerator roller; IN11 = 2011 natural fire area.

The highest diversity index (2.103) came from RA11, which could be due to the fact that this treatment has a better combination of density, frequency and coverage (Basáñez et al., 2008). The diversity index value of MDMt (1.484) is different from that obtained by González et al. (2013), of 1.843 un a dessert microphyllous shrub in Coahuila; this difference could be attributed to the history of land use where the study was carried out, which was subjected to intensive grazing until the year 2000. According to Rutledge et al. (2008) overgrazing may have a great impact upon the vegetation communities, since the loss of vigor in plants, increases the susceptibility to diseases, which reduces reproduction and the establishment of seeds, and, therefore, some important species for wildlife are bound to disappear.

In the natural fire treatment (IN11) a high species richness was attained (16) but Shannon's index (1.210) compared to control was smaller; this suggests that fire favored the whole elimination of the vegetal cover, but, as time went by, the community of plants in this treatment revealed a great diversity but with a low abundance of species. Miranda et al. (2009) state that the intensity of fire affects some unwanted species, it stops their propagation and propitiates the presence of other natives.

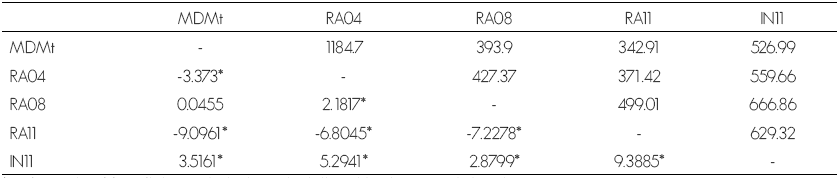

The diversity t test (Table 3) showed significant differences in most of the treatments (P < 0.05) except for MDMt-RA08 (t = 0.0455, (2), 005).

Table 3 Results of the t test to compare diversity among treatments.

*Significance of a=0.05. The horizontal row refers to the degrees of freedom; the vertical column, the statistical t.

Sørensen's index reveals that the most similar treatments are RA04 and RA08 with 76 %; in contrast, the most dissimilar are RA11 and MDMt with 42 %. Control is closer with RA08 (71 %) and RA04 (67 %), and RA11 and IN11 reached 55 %. The closeness between RA08 with control and the distance with RA11 with it means that the treated areas go back to their original condition in a period longer than five years (Table 4).

Table 4 Sørensen's Similitude Matrix for the treatments.

MDMt = Control; RA04 = 2004 aerator roller; RA08 = 2008 aerator roller; RA11 = 2011 aerator roller; IN11 = 2011 natural fire area.

In both indexes, diversity and similitude, RA11 is outstanding as it has a very poor closeness to the rest of the sites, which is conferred to the benefits brought by the aerator roller in three years, as it promotes spouting, since vegetation is not totally eliminated (Kunz, 2011). The use of this tool before the rainy season could be a crucial factor for the functioning of precipitation in the establishment or propagation of species either native or exotic after a mechanical disturb (Scifres and Polk, 1974). It is necessary to know the biology in the areas where this technique is planned to be used, as in those which have Opuntia, the roller might stimulate their propagation (McDonald, 2012). Also, some taxa emerge after the aerial part of their cover is removed (Ayala et al, 2014); such is the case of Larrea tridentata, which has asexual reproduction and tends to regenerate in one year (Monasmith et al., 2010); therefore, this procedure might not be effective in the removal of some of these plants.

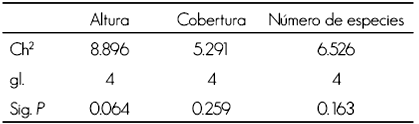

The Kruskall-Wallis test resulted in a non-significance difference among treatments in regard to the importance value index of the species (F= 2.463, G.L. 4, P = 0.261) or in the floristic structure and composition among treatments in which crown cover, height and means of the number or species per treatment were used as variables (Table 5).

Table 5 Result of the Kruskall-Wallis test.

Ch2= X squared; gl = Degrees of freedom; Sig. P = < 0.05.

In control (MDMt), IVI pointed out five dominant species: Opuntia engelmannii Salm-Dyck ex Engelm., Agave lechuguilla Torr., Jatropha dioica Sessé ex Carv., Larrea tridentata and Parthenium incanum Kunth; according to Brooks and Pyke (2001), some taxa of the Chihuahuan Desert such as the first two, have stimulated the suppression of forest fires and overgrazing as they change the structure of vegetation.

In RA04, Opuntia engelmannii, Larrea tridentata, Agave lechuguilla and Parthenium incanum are the most important and in RA08 they are the same as in control (MDMt), where only the values of dominance vary; in RA11 Larrea tridentata, Flourensia cernua, Jatropha dioica and Tiquilia greggii (Torr & A. Gray) A. T. Richardson keep that position. Finally, in IN11 Viguiera stenoloba S. F. Blake was the first one followed by Condalia spathulata A. Gray, Ziziphus obstusifolia (Hook. ex Torr & A. Gray) A. Gray and Agave lechuguilla.

In IN11 more than 90 % of the major species, such as Larrea tridentata and Agave lechuguilla were eliminated. Wright and Bailey (1982) describe that the first is poorly tolerant to fire, which might be due to its adaptation properties to drought and provokes a high mortality when more than 10 % of its aerial mass is burned (Brooks, 2007). However, in low intensity fires, these species may start to sprout after one year (Monasmith et al., 2010), which coincides with the plants in this treatment.

It has been documented that in areas as the Chihuahuan Desert where fires have occurred, after 16 months no A. lechuguilla sprouts were observed (Worthington and Corral, 1987). The reduction of Larrrea tridentata and the removal of A. lechuguilla promoted the presence of some herbs, a result that agrees with the findings of Ayala et al. (2009) who stated that the combination of aerial roller and fire increased herbaceous vegetation, which allowed that other native plants could compete.

The high number of species in IN11 suggests that fires stimulated the emergence of the material gathered in the soil seed bank and favored sprouting and diversity of species, which agrees with the findings of Pausas (2010) and Molina (2000), who confirm that some of them have the ability to sprout and add new members after the sinister, a feature that confers resistance not only to the populations but to the individuals in environments with frequent fires. In spite of being an uncontrolled fire, treatment IN11 fulfilled the objectives of prescribed burnings such as the removal of unwanted species, promoted regeneration and dominance of new species (Walkingstick and Liechty, 2009).

The use of aerial roller and fire used as treatments in this study seem not to have any influence upon IVI or in the structure and composition of species in the microphyll desert scrubland, a result that differs from those from Alanís et al. (2008) and Casas and Manzano (2009) in related studies in the semiarid zones at Northeastern Mexico in which a rechange of species was observed, which became evident in regard to the IVI of the species recorded in both investigations.

If the aim of these mechanical treatments in the dessert scrub is to remove the dominant species and to promote diversity, it would be wise to analyze cost-benefit of them in the long run of this kind of environments, as fire might be a lower cost and convenient option with similar results (McDonald, 2012).

Conclusions

The mechanical treatment and fire did not significantly modify the structure and composition of desert microphyllous scrub, however, the aerial roller proved to be an alternative to reduce short-term dominance of unwanted species such as Larrea tridentata, Opuntia engelmannii and Agave lechuguilla. In contrast, fire is proposed as a good alternative to increase biodiversity, promote regeneration, as well as presence and dominance of new species in the Chihuahuan microphyll desert scrubland. ■

Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Contribution by author

Romelia Medina Guillén: leadership of the whole experiment, vegetation sampling, data analysis and writing of the core of the manuscript; Israel Cantú Silva: development of the study, design and location of the experiment, supervision of the project and review of the manuscript; Eduardo Estrada Castillón: identification of floristic species at the herbarium, data analysis and review of the manuscript; Humberto González Rodríguez: statistical analysis, soil physical and chemical properties and review of the final versions of the manuscript; Jonás Adán Delgadillo Villalobos: establishment of the treatment of habitat management and assessment of the vegetal structure.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt), the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León and CEMEX-Naturaleza Sin Fronteras, A. C. for their support provided to carry out the actual investigation.

REFERENCES

Alanís R., E., J. Jiménez P., O. Aguirre C., E. J. Treviño G., E. Jurado Y. y M. A. González T. 2008. Efecto del uso de suelo en la fitodiversidad del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco. Ciencia UANL 11: 56-62. [ Links ]

Alanís, G., G. Cano y M. Rovalo. 1996. Vegetación y flora de Nuevo León. Una guía botánico-ecológica. Impresora de Monterrey. Monterrey, NL., México. 249 p. [ Links ]

Amaya R., J. 2009. El cultivo de la tuna Opuntia ficus indica. Gerencia Regional Agraria La Libertad. Trujillo, Perú. 18 p. [ Links ]

Analytical Software. 2003. Statistix 8. User´s manual. Tallahassee, FL, USA. 396 p. [ Links ]

Ayala F., A. Ortega, T. Fulbright, G. A. Rasmussen, D. L. Drawe y D. R. Synatzske. 2009. Efectos a largo plazo del roleo y fuego en la invasión de zacates exóticos en vegetación herbácea nativa en matorrales mixtos. : Memorias del VI Simposio Internacional de Pastizales 4 al 7 de noviembre. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León-Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey. Monterrey, NL., México. s/p. [ Links ]

Ayala, F. A., F. G. Denogean B., S. Moreno M., A. Durán, B. Martínez, L. Barrera y E. Gerlach. 2014. Rehabilitación y mejoramineto de hábitat para la fauna silvestre. Invurnus 9 (2): 18-22. [ Links ]

Basáñez J., A., L. Alanís J. y E. Badillo. 2008. Composición florística y estructura arbórea de la selva mediana subperennifolia del ejido "El Remolino", Papantla, Veracruz. Avances de Investigación Agropecuaria 12 (2): 3-21. [ Links ]

Boeing, W., K. Griffis K. and J. Jungels. 2013. Anuran habitat associations in the Northern Chihuahuan Desert, USA. Journal of Herpetology 48 (1): 103-110. [ Links ]

Brooks M. and D. Pyke. 2001. Invasive plants and fire in the deserts of North America. : Proceedings of the invasive species workshop: The role of fire in the spread and control of invasive species. fire conference. the first national congress on fire ecology, prevention, and management. Tall Members Research Station. Miscellaneous Publication No. 1. Tallahassee, FL, USA. pp. 1-14. [ Links ]

Brooks, M. L. 2007. Effects of land management practices on plant invasions in wildland areas. : Netwig, W. (ed.). Biological Invasions: Ecological Studies 193. Springer. Heidelberg, Germany. pp. 147-162. [ Links ]

Brower, J. E., J. H. Zar and C. N. von Ende. 1998. Field and laboratory methods for general ecology. McGraw-Hill. Boston, MA, USA. 273 p. [ Links ]

Calle D., Z. y E. Murgueitio 2008. El botón de oro: arbusto de gran utilidad para sistemas ganaderos de tierra caliente y de montaña. Ganadería y Ambiente. Centro para la investigación en sistemas sostenibles de producción agropecuaria CIPAV. Cali, Colombia. pp. 54-63. [ Links ]

Casas, N. and M. Manzano. 2009. Evaluation of the use of roller aerator for the rehabilitation of grazing lands and content of carbon in arid areas of northeastern Mexico. : Memorias del VI Simposio Internacional de Pastizales. 4 al 7 de noviembre. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León-Instituto Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey. Monterrey, NL., México. pp. 6-7. [ Links ]

Cervantes R., M. C. 2005. Plantas de importancia económica en zonas áridas y semiáridas de México. : Anais do X Encontro de Geógrafos da América Latina. 20-26 de março de 2005. Universidad de São Paulo. São Paulo, Brasil. pp. 3388-3407. [ Links ]

Challenger, A. 1998. Utilización y conservación de los ecosistemas terrestres de México. Pasado, Presente y Futuro. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México y Agrupación Sierra Madre S. C. México, D. F., México. pp. 689-713. [ Links ]

Challenger, A. y J. Soberón 2008. Los ecosistemas terrestres. : Capital natural de México, Conocimiento actual de la biodiversidad. Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad. Vol. 1. México, D. F., México. pp. 87-108. [ Links ]

Comisión Nacional Forestal (Conafor). 2011. Incendios Forestales 2011. Coordinación General de Conservación y Restauración.www.conafor.gob.mx (20 de mayo de 2011). [ Links ]

Díaz D., A., F. Hernández C., D. Jasso C., N. Aguilar, R. Rodríguez H. y R. Belmares C. 2008. Extractos normales y fermentados de Larrea tridentata y Fluorensia cernua sobre Fusarium oxysporum in vitro. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Monterrey, NL., México. http://www.somas.org.mx/pdf/pdfslibros/agriculturasostenible6/61/13.pdf (26 de noviembre de 2014). [ Links ]

Domínguez G., T. G., H. González R., E. Estrada C., I. Cantú S. y M. V. Gómez M. 2013. Diversidad estructural del matorral espinoso tamaulipeco durante las épocas secas y húmedas. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Forestales 4 (17): 106-123. [ Links ]

Espinoza, R. y J. Návar. 2005. Producción de biomasa, diversidad y ecología de especies en un gradiente de productividad en el matorral espinoso tamaulipeco del Nordeste de México. Revista Chapingo-Serie: Ciencias Foretales y del Ambiente 11 (1): 25-35. [ Links ]

Esqueda, M., M. Lizárraga, A. Gutiérrez, M. L. Coronado, R. Valenzuela, T. Raymundo, S. Chacón, G. Vargas y F. Barredo P. 2012. Diversidad Fúngica en Planicies del Desierto Central Sonorense y Centro del Desierto Chihuahuense. CIAD-UACJ-CESUES-IPN-INECOL-CICY. SNIB-CONABIO Proyecto GT016. Hermosillo, Son., México. 85 p. [ Links ]

Estrada, E., J. A. Villarreal y E. Jurado 2005. Leguminosas del norte del estado de Nuevo León, México. Acta Botánica Mexicana 73: 1-18. [ Links ]

Franco L., J. G., J. G. De la Cruz A., A. Cruz G., A Rocha R., S. Navarrete, G. Flores y M. Kato. 1989. Manual de Ecología. Ed. Trillas. México, D. F., México. 96 p. [ Links ]

González R., H., R. Ramírez L., I. Cantú S., M. V. Gómez M. y J. Uvalle S. 2010. Composición y estructura de la vegetación en tres sitios del estado de Nuevo León. Polibotánica 29: 91-106. [ Links ]

González R., H., R. Ramírez L., I. Cantú S., M. V. Gómez M., M. Cotera C., A.Carrillo P., J. J. Marroquín C. 2013. Producción de hojarasca y retorno de nutrientes vía foliar en un matorral desértico micrófilo en el Noreste de México. Revista Chapingo. Serie Ciencias Forestales y del Ambiente 19 (2): 249-262. [ Links ]

Hammer, Ø., D. A. T. Harper and P. D. Rayan. 2001. PAST: Paleontological Statistics Software Package for Educatuon and Data Analysis. Palaeontologia Electronica 4(1):1- 9. [ Links ]

Hernández J., R. Chávez y M. Sánchez. 2007. Diversidad y estrategias para la conservación de cactáceas en el semidesierto queretano. Biodiversitas 70: 6-9. [ Links ]

Hoyt, A. 2002. The Chihuahuan Desert: diversity at risk. Endangered Species Bulletin 27 (2): 16-17. [ Links ]

Hutcheson, K. 1970. A test for comparing diversities based on the Shannon formula. Journal of Theoretical Biology 29: 151-154. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Ecología-Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. (INE-Semarnat) 1997. Programa de manejo del área de protección de flora y fauna "Maderas del Carmen". México D. F., México. 127 p. [ Links ]

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Geografía e Informática (Inegi). 2014. Conjunto de Datos vectoriales de la Carta de Uso de Suelo y Vegetación: escala 1:250 000. Serie V. (Capa Unión). www.inegi.gob.mx. In:http://www.inegi.org.mx/geo/contenidos/recnat/usosuelo/Default.aspx (10 de octubre de 2014). [ Links ]

Juárez P., S. 2002. Extractos de Larrea tridentata con actividad fúngica e inhibición de la síntesis de aflatoxinas de especies del género Aspergillus . Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias con especialidad en Microbiología. Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. San Nicolás de los Garza, N L., México. 72 p. [ Links ]

Kovach Computing Services (KCS). 2007. Users´ manual. Multi-Variate Statistical Package Version 3.1. Pentraeth, Wales, United Kingdom. 137 p. [ Links ]

Kunz, D. 2011. Roller Chopper and Aerating. Habitat Management Techiques. The South Texas Quarterly. Texas Parks & Wildlife 2(2): 8-9. [ Links ]

Landázuri, P. y J. Tigrero. 2009. Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni, una planta medicinal. Bol. Téc. Edición Especial. ESPE. Sangolquí, Ecuador. 38 p. [ Links ]

Ledezma M., R. 2001. Fitosociología de Larrea tridentata Cav. en el matorral micrófilo en los municipios de Mina, Nuevo León y Castaños, Coahuila, México. Tesis de Maestría en Ciencias especialidad en Manejo de Vida Silvestre. Facultad de Ciencias Biológicas. Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. San Nicolás de los Garza, N L., México. 60 p. [ Links ]

Lira S., R. 2003. Estado actual del conocimiento sobre las propiedades biocidas de la Gobernadora (Larrea tridentata (D.C.) Coville). Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología 21 (2): 214-222. [ Links ]

Magurran, A. E. 1988. Ecological diversity and its measurement. Chapman and Hall. London, United Kingdom. 192 p. [ Links ]

Magurran, A. E. 2004. Measuring biological diversity. Blackwell Science Ltd. Oxford, United Kingdom. 215 p. [ Links ]

McDonald, A. 2012. Mechanical brush management in Trans-Pecos, Texas. : Proceedings of the Trans-Pecos Wildlife Conference 2012. Sul Ross State University. Alpine, TX, USA. pp. 13-16. [ Links ]

Menke, S. B. 2003. Lizard community structure across a grassland-creosote bush ecotone in the Chihuahuan Desert. Canadian Journal of Zoology 81(11):1829-1838. [ Links ]

Miranda B., R., C. Ortega O., A. Rico D., R. Sandoval R., R. Quintana M., O. Rivero H. and O. Viramontes O. 2009. Use of fire as an alternative to control natal grass (Melinis repens ) in the estado de Chihuahua.: Memorias del VI Simposio Internacional de Pastizales. 4 al 7 de noviembre. UANL-ITESM. Monterrey, NL., México. 16 p. [ Links ]

Molina T., D. M. 2000. Fuego prescrito. : Vélez, R. (ed): La defensa contra incendios forestales: Fundamentos y experiencias. McGraw-Hill. Madrid, España. pp. 36-41. [ Links ]

Monasmith, T. J., S. Demarais, J. J. Root and C. M. Britton 2010. Short-term fire effects on small mammal populations and vegetation of the northern Chihuahuan Desert. International Journal of Ecology Vol. 10. Article ID 189271. 9 p. DOI:10.1155/2010/189271. [ Links ]

Mostacedo, B. y T. S. Fredericksen. 2000. Manual de métodos básicos de muestreo y análisis en ecología vegetal. Bolivia Sustainable Forest Management Project (BOLFOR). Santa Cruz, Bolivia. 87 p. [ Links ]

Ordóñez M., M. 2003. Propagación in vitro de Mammillaria voburnensis Scheer (Cactaceae). Tesis de Maestría. Facultad de Ciencias Químicas y Farmacia. Escuela de Biología. Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala. Guatemala, Guatemala. 70 p. [ Links ]

Ott, L. 1993. An introduction to statistical methods and data analysis. Duxbury Press Boston, MA, USA. 775 p. [ Links ]

Pausas, J. G. 2010. Fuego y evolución en el Mediterráneo. Investigación y Ciencia 407: 56-63. [ Links ]

Peñuelas R., O., J. Arellano M., M., Gutiérrez, L. Castro y C. Mungarro 2011. Larrea tridentata potencial solución para la desinfección de suelo. Ide@s concyteg 6 (71): 605-616. [ Links ]

Rutledge, J., T. Bartostewitz and A. Clain. 2008. Stem count index. A habitat appraisal method for south Texas. Texas Park and Wildlife Department. Austin, TX, USA. 24 p. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 1978. Vegetación de México. Limusa México, D. F., México. 432 p. [ Links ]

Rzedowski, J. 2006. Vegetación de México. Conabio México, D. F., México. 1ª. edición digital. 504 p. http://www.conabio.gob.mx/institucion/centrodoc/doctos/librosdigitales/VegetaciondeMexico/Portadaypaglegales.pdf (13 de septiembre de 2014). [ Links ]

Sæther, B., S. Engen and V. Grotan. 2013. Species diversity and community similarity in fluctuanting environments: parametric approaches using species abundance distributions. Journal of Animal Ecology 82(4): 721-738. [ Links ]

Scifres, C. J. and D. B. Polk, Jr. 1974. Vegetation response following spraying a light infestation of honey mesquite. Journal of Range Management 27(6): 462-465. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales (Semarnat). 2012. Programa Anual de Trabajo 2012. Versión Ejecutiva. Tlalpan, México D. F., México. http://www.semarnat.gob.mx/programas/programaanual-de-trabajo-2012 (25 de marzo de 2014). [ Links ]

Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto (SPP). 1982a. Carta estatal de edafología. Dirección General de Geografía del Territorio Nacional. Cartas H 13-9 y H13-12. Esc: 1: 250 000. México, D.F.,México. s/p. [ Links ]

Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto (SPP). 1982b. Carta estatal de geología. Dirección General de Geografía del Territorio Nacional. Cartas H 13-9 y 13-12. Esc: 1:250 000. México, D.F., México. s/p [ Links ]

Secretaría de Programación y Presupuesto (SPP). 1983. Síntesis geográfica de Coahuila y anexo cartográfico. México, D. F., México. s/p [ Links ]

Steel, R. and J. Torrie. 1980. Principles and procedures of statistics. A biometrical approach (2nd. ed.). McGraw-Hill Book Company. New York, NY, USA. 632 p. [ Links ]

Tinajero, R. y R. Rodríguez E. 2012. Efecto de la fragmentación del matorral desértico sobre poblaciones del aguililla cola-roja y el cernícalo americano en Baja California Sur, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 28 (2): 427-446. [ Links ]

Villarreal, H., M. Álvarez C S., F. Escobar, G., Fagua, H. Mendoza, M. Ospina y A. M. Umaña. 2004. Manual de métodos para el desarrollo de inventarios de biodiversidad. Programa de Inventarios de Biodiversidad. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt. Bogotá, Colombia. 236 p. [ Links ]

Villarreal, J. Á. y J. Valdés. 1992-1993. Vegetación de Coahuila, México. Revista de Manejo de Pastizales 6 (1-2): 9-18. [ Links ]

Walkingstick T. and H. Liechty. 2009. Why we burn: prescribed burning as a management tool. University of Arkansas. Division of Agriculture. Agriculture and Natural Resources. Cooperative Extension Service. http://www.researchgate.net/publication/238766246_Why_We_Burn_Prescribed_Burning_as_a_Management_Tool (26 de octubre de 2014). [ Links ]

Worthington R. D. and R. D. Corral 1987. Some effects of fire on shrubs and succulents in a Chihuahuan Desert community in the Franklin Mountains, El Paso County, Texas.: Contributed papers of the second symposium on resources of the Chihuahuan Desert regions. The Chihuahuan Desert Research Institute. Alpine, TX, USA. 9 p. [ Links ]

Wright H. A. and A. W. Bailey 1982. Fire ecology, United States and southern Canada. John Wiley and Sons. New York, NY, USA. 501 p. [ Links ]

Received: February 16, 2015; Accepted: July 20, 2015

texto em

texto em