Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias pecuarias

versión On-line ISSN 2448-6698versión impresa ISSN 2007-1124

Rev. mex. de cienc. pecuarias vol.10 no.2 Mérida abr./jun. 2019

https://doi.org/10.22319/rmcp.v10i2.4370

Technical notes

Similarity in plant species consumed by goat flocks in the tropical dry forest of the Cañada, Oaxaca

a Instituto de Ecología A.C. Red Biología y Conservación de Vertebrados, km 2.5 Carretera Antigua Coatepec No. 351, Congregación del Haya, Xalapa 91070, Veracruz, México.

b Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. Escuela de Ingeniería Agrohidráulica, Unidad Chiautla de Tapa. Puebla, México.

Management of goats (Capra hircus) in extensive systems is a common practice in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve (TCBR), Mexico. This study analyzes the similarity in plant consumed by goat flocks in landscape at the Cañada region, Oaxaca. Eight (8) flocks were sampled in different locations during the 2012 rainy season and 2013 dry season. To determine spatial and temporal similarity among the flocks, depending upon the consumed plant species, it was used hierarchical agglomerative clustering methods in the R program. The goats consumed a total of 84 plant species, of which 30 constituted 75 % of the diet. According to the similarity analysis, Mimosa sp. and Acacia cochiliacantha were the species consumed by all flocks in both seasons; while Eleusine indica, Prosopis leavigata and Opuntia sp. were the next most important, depending on the season. The Tecomavaca herd showed lower similarity than the other flocks. The results of the present study contribute to furthering the knowledge regarding the foraging habits of goats in tropical dry regions where the seasonality of the resources is very contrasting.

Key words: Capra hircus; Extensive systems; Multivariate methods; Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve

El manejo de caprinos (Capra hircus) en sistemas extensivos es una práctica común en la Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán (RBTC), México. En el presente estudio se analizó la similitud de las especies de plantas consumidas por los caprinos de diferentes rebaños en un paisaje de la Cañada en Oaxaca. Se siguió a ocho rebaños en diferentes localidades durante las épocas de lluvias 2012 y la de seca 2013. Para determinar la similitud espacial y temporal entre los rebaños dependiendo de las plantas consumidas, se emplearon métodos de análisis multivariado, específicamente de agrupamiento jerárquico en el programa R. Los caprinos consumieron 84 especies, de las cuales 30 constituyen el 75 % de la dieta. De acuerdo a los análisis de similitud, Mimosa sp. y Acacia cochiliacantha fueron las especies consumidas con mayor frecuencia por todos los rebaños; mientras que Eleusine indica, Prosopis leavigata y Opuntia sp. fueron las siguientes en importancia. El rebaño de la localidad Tecomovaca fue el menos similar al resto de los rebaños estudiados. Estos resultados contribuyen al entendimiento de los hábitos de forrajeo de los caprinos en región tropical seca, donde la disponibilidad de recursos es marcadamente estacional.

Palabras clave: Capra hircus; Sistema extensivo; Métodos multivariados; Reserva de Biósfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán

In Mexico, goats represent an important source of protein1,2. For example, the national census of 2011 estimated a population of 9 million goats3. Management of goats is a particularly widespread practice in the state of Puebla4,5, but it is less developed in Oaxaca6. The Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve (TCBR) in the states of Puebla and Oaxaca in central Mexico is characterized by high biodiversity of species and endemism7. Within the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, there are estimated to be around 5,000 goat farmers8, who mainly practice subsistence farming9. The goats have been present since their introduction during the colonial period and currently represent one of the main productive activities in many villages in and around the TCBR4. In common with other arid and semi-arid regions2,3, the extensive system is the main practice in the TCBR. This is based on leading the herds along fixed or migratory routes to browse on the hills, roadsides and riparian areas4.

Considering that the TCBR is a natural protected area, it is important to evaluate the influence of goats on the vegetation structure2,10,11 and identify possible competitive interactions with wild ungulates such as the white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianus12. In this context, this study analyzes the similarity in plant consumed by goat herds in landscape at the Cañada region, Oaxaca, using hierarchical agglomerative clustering methods. To determine similarities among the herds in terms of the plant species consumed, in this study were used hierarchical agglomerative clustering methods through multivariate cluster analyses13. The objective of clustering is to recognize discontinuous subsets in an environment that is sometimes discrete and most often perceived as continuous in ecology14. Specifically, clustering consists of partitioning the collection of objects under study. For this propose several similarity indices, as for example Sorensen, Jaccard and Morisita, had been employed for computing similarity or dissimilarity among pairwise collection objects. Clustering methods, as for example, single linkage, complete-linkage, average agglomerative and Ward's minimum variance, are employed to agglomerate objects on basis of pairwise distance given the similarities or dissimilarities, depending on each case13. To interpret and compare the hierarchical clustering results, cophenetic correlation distances were calculated for each clustering. Briefly, the cophenetic index between two objects in a dendogram is the distance at which the objects become members of the same group. The interpretation of this index is similar to the Pearson’s r correlation coefficient14. Therefore, to test the hypothesis of the present study, hierarchical agglomerative clustering methods were employed.

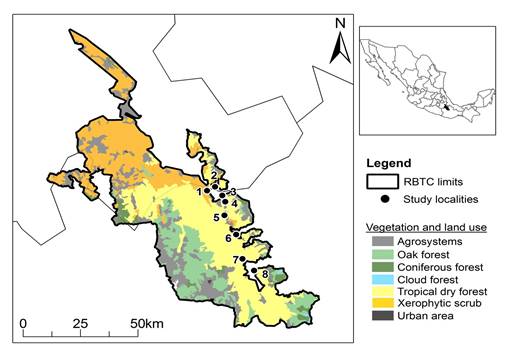

The study was conducted at the region of the Cañada in Oaxaca, within the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve (TCBR) in Mexico (Figure 1). The TCBR is locate in the extreme southeast of the state of Puebla and northeast of Oaxaca, between 17° 39' - 18° 53' N and 96° 55' - 97° 44' W. It is 490,187 ha in area and the altitude ranges from 600 to 2,950 m asl. Annual mean temperature ranges from 18 and 22 °C, while the annual precipitation varies between 250 and 500 mm15. The main vegetation types in the region are: crassicaule scrub dominated by columnar cacti of the genus Neobuxbaumia (8 % of the reserve territory) and rosetophyllous scrub (10 %), mostly in the northern area of the TCBR; while tropical dry forest (29 %) dominate mainly in the Cañada region; oak and pine forest in the upper mountains (21 %); as well as other vegetation types (10 %). Land use is mostly for agriculture, livestock and forestry (22 %)15.

Figure 1 Geographic location of the eight studied sites at La Cañada in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve, Mexico. Sites: Casa Blanca (1), Coxcatlán (2), Teotitlán (3), Toxpalan (4), Los Cues (5), Tecomavaca (6), Cuicatlán (7) and Chicozapotes (8)

The study was conducted in eight locations: Coxcatlán state of Puebla, and Casa Blanca, Teotitlán, Toxpalan, Los Cues, Tecomavaca, Cuicatlán and Chicozapotes state of Oaxaca (Figure 1). At each location, it was follow the same flock once during the rainy season (September to November 2012) and once again in the dry season (April to June 2013). The selection of these flocks depended on the interest of the goat farmers in participating in the study. Traditionally, the extensive system consists of moving the flock daily to foraging sites along predefined routes. In addition, the flock size and total foraging time depends upon the owner’s experience, among other factors16. In the studies sites, the mean herd size and forage time were 70 goats and 4.2 h, respectively.

To determine the main plants consumed by the goats, the animals were directly observed during foraging17. The selection of these herds depended on the interest of the goatherds in participating in the study. In the study site, the goat farmers move their animals to forage outside the villages almost every day. The goats are therefore accustomed to the presence of people, which eliminates the possibility of bias during observation of foraging activities18. Every 20 min, a different focal animal was selected and the number of plants of each species consumed was recorded over a period of 10 min. For each flock, it was recorded the number of plants species consumed per the flock during both the rainy and dry seasons, was recorded18,19. The number of focal animals varied depending of the travel time of the sampled flock (n= 57 and 58 goats for rainy and dry seasons, respectively). Simultaneously, there were collected plants for taxonomic determination in the herbarium strata and by other sources20. However, the rugged topography, dense vegetation and speed of movement by the goats made it impossible to collect all plants consumed.

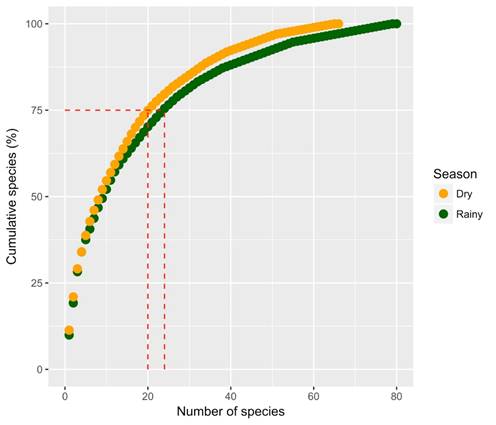

Individually observed goats cannot be true replicates as they do not take grazing decisions independently from one another21. Therefore, the information was grouped considering flock as replicate. It was calculated the cumulative curve of the number of species consumed by the goats during the rainy and dry seasons. A relatively arbitrary shortcut of 75 % was employed to determine the principal plant species and was used a Chi-square test to evaluate differences between seasons22.

To determine similarities among the eight flocks in terms of the plant species consumed, hierarchical agglomerative clustering methods were used through multivariate cluster analyses23. For this purpose, the species that represented 75 % of the total consumed plants was employed for clustering the flocks. This shortcut percent is subjective but represents the point where the cumulative curve of the relationship between number of species consumed species, begins to reach the asymptote. Analyses were performed separately for each season. The Horn-Morisita similarity index was selected for the number of plants consumed by species in this study. Four clustering methods were calculated: single linkage, complete-linkage, average agglomerative (UPGMA) and Ward's minimum variance23. To examine the species content of the clusters depending on group memberships, it was used the vegan R package23. This package provides tools for descriptive community ecology. Specifically, it has the most basic functions of diversity analysis, community ordination and dissimilarity analysis. Finally, the results of these analyses are presented as a heat map of the doubly ordered table of the consumed plants, with a dendrogram of cluster sites. All analyses in this study were performed in R version 3.2.324.

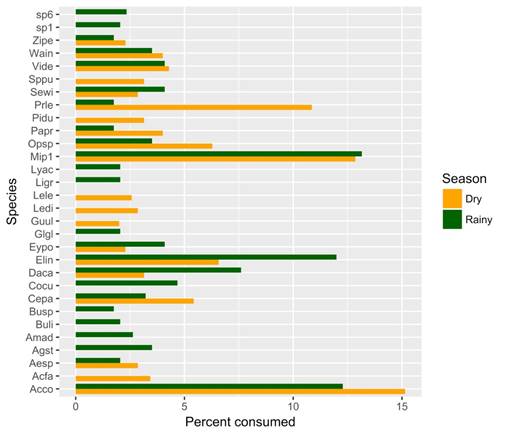

The goats consumed 82 and 65 species during the rainy and dry season, respectively (Table 1). However, according to the cumulative curve, 75 % of the diet was constituted by 30 species: 24 species during the rainy season and 20 species in the dry season (Figure 2). The main species in both seasons were Mimosa sp., Acacia cochiliacantha and Eleusine indica; during the rainy season was Dalea carthagenensis; while in the dry season were Prosopis leavigata, Opuntia sp. and Ceiba parvifolia, which differed significantly (Figure 3; P= 0.0001).

Table 1 List of plant species consumed by goats during the rainy and dry seasons at La Cañada, Oaxaca

| Plant species | Abbreviation | Rainy season | Dry season | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of plants |

% * | Number of plants |

% | ||

| Eleusine indica | Elin | 56 | 8.6 | 28 | 5.4 |

| Mimosa sp.1 | Misp | 51 | 7.8 | 50 | 9.6 |

| Acacia cochliacantha | Acco | 49 | 7.5 | 61 | 11.7 |

| Dalea carthagenensis | Daca | 27 | 4.2 | 10 | 1.9 |

| Agrostis stolonifera | Agst | 21 | 3.2 | 10 | 1.9 |

| Viguiera dentata | Vide | 16 | 2.5 | 18 | 3.4 |

| Cordia curassavica | Cocu | 16 | 2.5 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Eysenhardthia polystachya | Eypo | 14 | 2.2 | 8 | 1.5 |

| Senna wislizeni | Sewi | 14 | 2.2 | 10 | 1.9 |

| Aegopogon sp. | Aesp | 13 | 2.0 | 16 | 3.1 |

| Opuntia sp. | Opsp | 13 | 2.0 | 24 | 4.6 |

| Ceiba parvifolia | Cepa | 12 | 1.8 | 22 | 4.2 |

| Waltheria indica | Wain | 12 | 1.8 | 14 | 2.7 |

| Amphipterygium | Amad | 9 | 1.4 | 3 | 0.6 |

| adstringens | Ligr | 8 | 1.2 | - | - |

| Lippia graveolens | nd | 8 | 1.2 | - | - |

| nd | Phau | 8 | 1.2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Phragmites australis | Papr | 7 | 1.1 | 16 | 3.1 |

| Parkinsonia praecox | Prle | 7 | 1.1 | 43 | 8.2 |

| Prosopis leavigata | Zipe | 7 | 1.1 | 11 | 2.1 |

| Ziziphus pedunculata | Buli | 7 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Bursera linanoe | Glgl | 7 | 1.1 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Glycyrrhiza glabra | nd | 6 | 0.9 | 5 | 1.0 |

| nd | Busp | 6 | 0.9 | 6 | 1.1 |

| Bursera sp. | Sapr | 5 | 0.8 | - | - |

| Sanvitalia procumbens | nd | 5 | 0.8 | 4 | 0.8 |

| nd | Crpr | 5 | 0.8 | - | - |

| Cyrtocarpa procera | Ledi | 5 | 0.8 | 12 | 2.3 |

| Leucaena diversifolia | nd | 5 | 0.8 | 6 | 1.1 |

| nd | Mame | 4 | 0.6 | - | - |

| Malpighia mexicana | Ipsp | 4 | 0.6 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Ipomoea sp. | Cili | 4 | 0.6 | 5 | 1.0 |

| Citrus limon | Pool | 3 | 0.5 | - | - |

| Portulaca oleracea | Brde | 3 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Brachiaria decumbens | Laca | 3 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Lantana camara | Sosp | 3 | 0.5 | - | - |

| Solanumzp | Agho | 3 | 0.5 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Agave horrida | Ages | 3 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Ageratina espinosarum | Lyac | 3 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Lysiloma acapulcense | Lyte | 3 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Lysiloma tergeminum | nd | 3 | 0.5 | - | - |

| nd | Pafo | 3 | 0.5 | - | - |

| Passiflora foetida | Plru | 3 | 0.5 | 7 | 1.3 |

| Plumeria rubra | Sotr | 3 | 0.5 | - | - |

| Solanum tridynamum | Tudi | 3 | 0.5 | - | - |

| Turnera diffusa | Maza | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Manilkara zapota | Sila | 2 | 0.3 | - | - |

| Simsia lagascaeformis | Acfa | 2 | 0.3 | 12 | 2.3 |

| Acacia farnesiana | Anle | 2 | 0.3 | - | - |

| Antigonon leptopus | Busp1 | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Bursera sp.1 | Caza | 2 | 0.3 | - | - |

| Calea zacatechichi | Guul | 2 | 0.3 | 7 | 1.3 |

| Guazuma ulmifolia | Lele | 2 | 0.3 | 9 | 1.7 |

| Leucaena leucocephala | Matr | 2 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Matelea trachyantha | Pawe | 2 | 0.3 | 3 | 0.6 |

| Pachycereus weberi | Pidu | 2 | 0.3 | 11 | 2.1 |

| Pithecellobium dulce | Plsp | 2 | 0.3 | - | - |

| Platanus sp. | Plbu | 2 | 0.3 | - | - |

| Plocosperma buxifolium | Posp | 2 | 0.3 | - | - |

| Polygonum sp. | Saal | 2 | 0.3 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Salix alba | Sppu | 2 | 0.3 | 11 | 2.1 |

| Spondias purpurea | Amhy | 1 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Amaranthus hybridus | Titu | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Tithonia tuberformis | Alch | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Allionia choisyi | Cnte | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Cnidoscolus tehuacanensis | Acco | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Acacia coulteri | Acme | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Acrocomia mexicana | Agke | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Agave kerchovei | Agpo | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Agave potatorum | Bufa | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Bursera fagaroides | Cesp | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Ceiba sp. | Cepa | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Celtis pallida | Cosc | 1 | 0.2 | - | - |

| Commicarpus scandens | Come | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Condalia mexicana | Hete | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Hechtia tehuacana | Mool | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Moringa oleifera | Psan | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Pseudosmodingium | Scba | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.4 |

| andrieuxii | Soro | 1 | 0.2 | - | - |

| Schinopsis balansae | nd | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Solanum rostratum | nd | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| nd | Asvi | - | - | 5 | 1.0 |

| nd | Pade | - | - | 2 | 0.4 |

| Astianthus viminalis | Stpr | 1 | 0.2 | 4 | 0.8 |

| Panicum decolorans | |||||

| Stenocereus pruinosus | |||||

(*) percentage of the total in each season, (nd) non-determined species.

Figure 2 Cumulative curve of the relationship between number of species consumed by goats during the dry and rainy seasons. Dashed red lines show that, considering arbitrary shortcut of 75 %, 20 and 24 plants species were consumed in each season

Figure 3 Percentage of the principal plant species (75 % of the total) consumed by goats during the dry and rainy seasons.

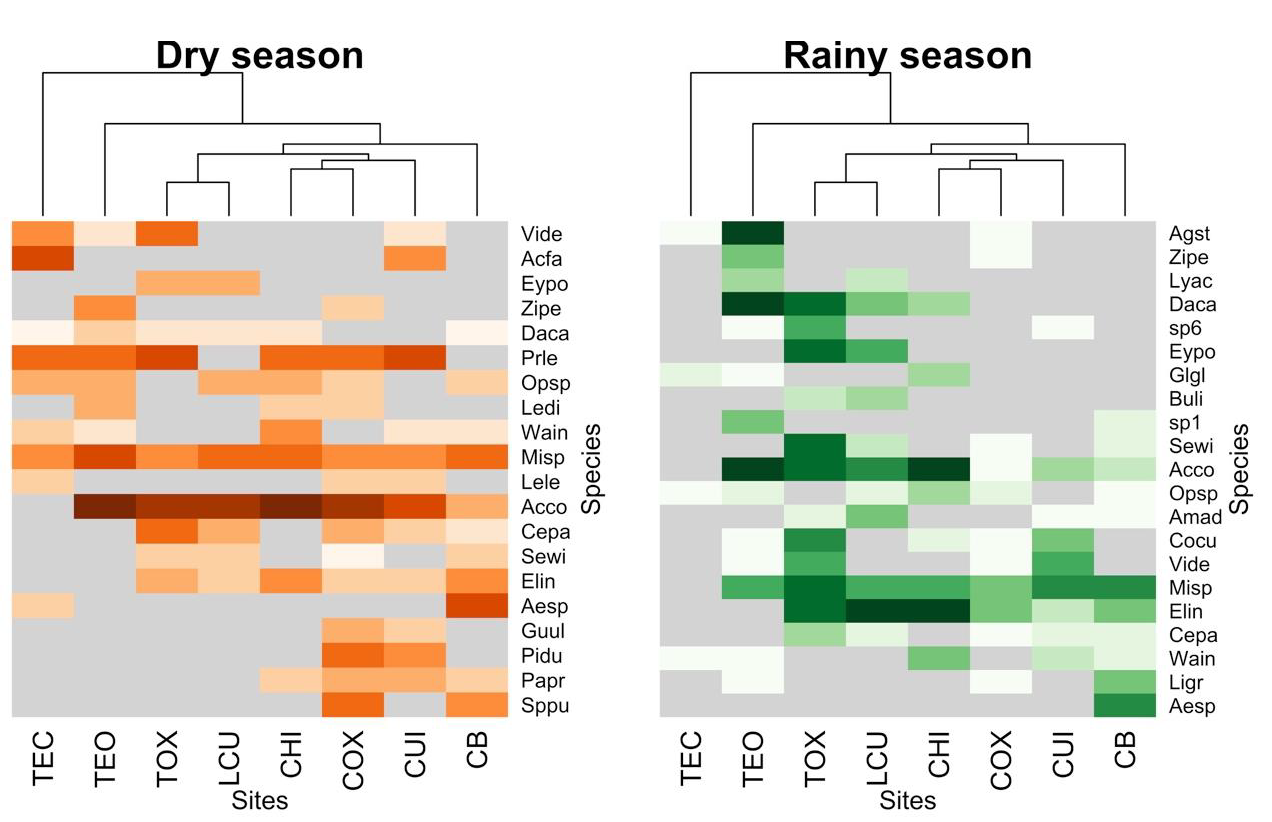

The four clustering methods (single linkage, complete-linkage, UPGMA and Ward) produced slightly different dendrograms. Calculation of the cophenetic distance correlation coefficient (r= 0.92 in the rainy season and r= 0.86 in the dry season) suggested that UPGMA was the optimum clustering method for the matrix data. The Horn-Morisita similarity coefficients varied among pairwise locations and seasons (Table 2). Mimosa sp. and Acacia cochiliacantha were the species consumed by all flocks in both seasons; while Eleusine indica, Prosopis leavigata and Opuntia sp. were the next most important, depending on the season. During the rainy season flocks from Tecomavaca and Teotitlán showed lower similarity relative to the other flocks; while dry season, flocks from Tecomavaca and Casa Blanca showed lower similarity relative to the other flocks (Figure 4).

Table 2 Horn-Morisita similarity coefficients among pairwise sites during the rainy and dry seasons

| CB+ | CHI | COX | TOX | CUI | LCU | TEO | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainy season | |||||||

| CHI | 0.582 | ||||||

| COX | 0.707 | 0.72 | |||||

| TOX | 0.471 | 0.604 | 0.601 | ||||

| CUI | 0.536 | 0.640 | 0.694 | 0.685 | |||

| LCU | 0.549 | 0.723 | 0.664 | 0.800 | 0.499 | ||

| TEO | 0.353 | 0.547 | 0.401 | 0.481 | 0.401 | 0.495 | |

| TEC | 0.080 | 0.369 | 0.138 | 0 | 0.088 | 0.04 | 0.256 |

| Dry season | |||||||

| CHI | 0.610 | ||||||

| COX | 0.590 | 0.685 | |||||

| TOX | 0.480 | 0.678 | 0.611 | ||||

| CUI | 0.454 | 0.718 | 0.808 | 0.700 | |||

| LCU | 0.633 | 0.705 | 0.579 | 0.761 | 0.526 | ||

| TEO | 0.456 | 0.844 | 0.669 | 0.675 | 0.617 | 0.673 | |

| TEC | 0.381 | 0.477 | 0.35 | 0.463 | 0.615 | 0.275 | 0.511 |

+ Sites abbreviations: Coxcatlán (COX), Casa Blanca (CB), Teotitlán (TEO), Toxpalan (TOX), Los Cues (LCU), Tecomavaca (TEC), Cuicatlán (CUI) and Chicozapotes (CHI).

Figure 4 Classification of the sites according with the similarity in plant species consumed by goats during the dry and rainy seasons. The dark-light color gradient represents from more to less species consumed. Very low or no consumption it is represent by gray color. In the upper part, the dendrogram of studied sites classification uses the UPGMA average agglomerative clustering method

The species richness of plants consumed by the goats in the region of La Cañada was similar to that reported in regions neighboring the TCBR. For example, in the northern region, between 40 and 80 species have been reported to be consumed by the goats in the dry and rainy seasons, respectively5,25. Among the principal genera consumed by goats were Bursera, Jatropha, Fouquieria, Leucaena, Pithecellobium, Acacia, Guazuma, and Prosopis25,26. In other tropical region has been reported that, of the 19 trees species consumed during the year, Mimosa was by far the most frequently selected species; grass was a large component of the goat diet in the early wet period, while browsed leaves were an important source of forage during the dry periods28. In particular, the dry season is the most critical phase for the maintenance of flocks in this region. It has been documented that the goats lose bodyweight significantly during this period due to deficiencies in dietary protein and phosphorus29. The animals mainly browse on leguminous plants during the dry season30.

During periods of forage scarcity, goats typically increase their search effort as nutrient intake decreases. The increased consumption of woody species observed during this period increases the grazing pressure on local vegetation29. For this reason, such as Opuntia spp. and Agave salmiana have been suggested as dietary supplements, along with the fruits of Yucca periculosa and pods of Prosopis laevigata and Acacia subangulata combined with the traditional maize stubble29. In other semiarid regions, Prosopis laevigata and Opuntia sp. are used as supplements, considering their nutritional characteristics and their capacity for growth in conditions of low water availability31. In particular, the cladodes of the cacti and their fruits are used as an emergency food source, providing energy and water in times of drought, while the herbaceous plants provide protein in the rainy season3.

Small ruminants, such as goats and sheep, and even wild animals such as the white-tailed deer, select their diet from a broad range of plant species, which differ in terms of nutrient content and availability over the course of the year19. At the end of fall and beginning of winter, there is a lack of quality forage for which reason it is necessary to supplement the diet of the goats. The deficiency of crude protein in the goat´s diet limits the digestion of fiber and minerals by the animals, causing slow growth, reduced immunological function, anemia, edema and death32. Of the plant species consumed, those with the highest contents of protein (>20 %) are Ziziphus pedunculata, Prosopis laevigata and Ceiba parvifolia; other species that fulfill the minimum requirements for the goats are Mimosa sp., Viguiera dentate, Walteria indica and Solanum tridynamum33. Fiber contributes significantly to balance nutritional requirements32,34. Of the plants analyzed, the highest fiber content is presented by Agrostis stolonifera collected in the rainy season. Of the consumed plants, those with the highest quantity of neutral detergent fiber, acid detergent fiber were Mimosa sp., Opuntia sp., Viguiera dentate, Acacia farnesiana, Opuntia sp. and Ziziphus pedunculata33. The shrub species of the genera Prosopis, Mimosa and Acacia presented high metabolizable energy compared to some tree, cactus and herbaceous plants3. The metabolizable energy in Prosopis and Acacia during the dry season exceeded the requirements of the goats35.

Hierarchical agglomerative clustering methods through multivariate cluster analyses13 allowed determination of similarities among the eight flocks depending upon the consumed plant species. These methods are common in taxonomic and ecological studies14. Based on 75 % of the principal species consumed and using heat maps, the eight studied flocks were classified into different clusters in each season. Specifically, the Tecomovaca flock showed lower similarity compared to the other flocks. Local differences in plant species abundance and the presence of some specific species, explained the clustering of the flocks in the rainy and dry seasons.

Finally, the results of the present study contribute to furthering the knowledge regarding the foraging habits of goats in tropical dry landscapes where the seasonality of the resources is very contrasting, as is the case in the Cañada which has been little studied compared to the arid and semiarid zones of Mexico. Some of the plants consumed could be used in the production of silage by family microbusinesses in order to feed the goats with native plants. Due to their availability in the zone as well as nutritional content, the species Ceiba parvifolia, Waltheria indica, Prosopis leavigata, Solanum sp. and Sanvitalia procumbens could be collected in the rainy season for tedding or ensilaging and subsequent use as a food supplement in the dry season or when the animals are corralled. These results are valuable for the management and conservation of the studied habitats as they further the understanding of goat habitat and diet selection in different periods.

The studied goat flocks consumed 65 to 82 plant species during the dry and rainy seasons in the Cañada region of Oaxaca State. However, the main species were Mimosa sp., Acacia cochiliacantha, Eleusine indica, Dalea carthagenensis, Prosopis leavigata, Opuntia spp. and Ceiba parvifolia. Some of these species have been reported in other regions. Hierarchical agglomerative clustering methods through multivariate cluster analyses allowed the determination of similarities among the eight flocks according to the plant species consumed. These analyses show that the goats of different locations in the Cañada region consumed relatively similar plant species.

Acknowledgements

The study received financial and logistical support of the CONACYT projects CB-2009-01-130702 and CB-2015-01-256549; and the Red de Biología y Conservación de Vertebrados del Instituto de Ecología A.C. Thank also to T. Pérez-Pérez, R. Rodriguez, and A. Sandoval-Comte. We thank the authorities and people of the studied sites. K. MacMillan reviewed the English version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

1. Rebollar S, Hernández J, Rojo R, Guzmán E. Gastos e ingresos en la actividad caprina extensiva en México. Agron Mesoam 2012;23(1):159-165. [ Links ]

2. Zárate JL. Livestock and natural resources in a nature reserve in south Sonora, Mexico. Trop Subtrop Agroecosyst 2012;15(2):187-197. [ Links ]

3. Guerrero-Cruz MM. La caprinocultura en México, una estrategia de desarrollo. Rev Universt Digital Cienc Soc 2010;1(1):2-7. [ Links ]

4. Hernández-H ZJS. The goat farming in the Puebla (Mexico) livestock production: goat contribution and production systems. Arch Zootec 2000;49(187):341-352. [ Links ]

5. Hernández-H JE, Franco FJ, Villarreal- Espino OA, Aguilar LM, Sorcia MG. Identificación y preferencia de especies arbóreo-arbustivas y sus partes consumidas por el ganado caprino en la Mixteca Poblana, Tehuaxtla y Maninalcingo, México. Zootec Trop 2008;26(3):379-382. [ Links ]

6. Mendoza A, Ortega-Sánchez JL. Capriculture characterization in the municipality of Tepelmeme Villa de Morelos, Oaxaca, Mexico. Rev Chapingo Zonas Áridas 2009;8(1):75-80. [ Links ]

7. Dávila P, Arizmendi MC, Valiente-Banuet A, Villaseñor JL, Casas A, Lira R. Biological diversity in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley, Mexico. Biodivers Conserv 2002;11(3):421-442. [ Links ]

8. Baraza E, Estrella-Ruiz JP. Manejo sustentable de los recursos naturales guiado por proyectos científicos en la mixteca poblana mexicana. Ecosistemas 2008;17(2):3-9. [ Links ]

9. Ortega RH, Ortega-Paczka R, Zavala-Hurtado JA, Baca del Moral J, Martínez-Alfaro MA. Diagnóstico ambiental y estrategias campesinas en la Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán, municipio de Zapotitlán, estado de Puebla. Rev Geografía Agr 2008;41(1):55-71. [ Links ]

10. Baraza E, Valiente-Banuet A. Efecto de la exclusión de ganado en dos especies palatables del matorral xerófilo del Valle de Tehuacán, México. Rev Mex Biodivers 2012;83(4):1145-1151. [ Links ]

11. Castro HG, Figueroa DG, Hernández FG, de Coss AL, Ruiz RP. Evaluación de áreas ganaderas en la zona de amortiguamiento de una reserva natural en Chiapas, México. Rev Asoc Interprofesional Desarrollo Agrario 2013;1(1):69-85. [ Links ]

12. Vasquez Y, Tarango L, López-Pérez EN, Herrera J, Mendoza G, Mandujano S. Variation in the diet composition of the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) in the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Biosphere Reserve. Rev Chapingo S Cienc Forestales Ambientales 2016;22(3):87-98. [ Links ]

13. Bocard D, Gillet F, Legendre P. Numerical Ecology with R. Springer. 2011 [ Links ]

14. Legendre P, Legendre L. Numerical ecology. 2nd Eng ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1998. [ Links ]

15. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Protegidas (CONANP). Programa de Manejo Reserva de la Biosfera Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Comisión Nacional de Áreas Naturales Protegidas. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales. México, DF. 2013. [ Links ]

16. Reséndiz-Melgar RC, Díaz MJ, Lemos-Espinal JA. Forrajeo de ganado caprino en el Valle de Zapotitlán de las Salinas, Puebla, México. Rev Mex Cienc Forest 2005;30(1):45-92. [ Links ]

17. Agreil C, Meuret M. An improved method for quantifying intake rate and ingestive behavior of ruminants in diverse and variable habitats using direct observation. Small Ruminant Res 2004;54(1-2):99-113. [ Links ]

18. González-Pech PG, Torres JFJ, Sandoval CA. Adapting a bite coding grid for small ruminants browsing a deciduous tropical forest. Trop Subtrop Agroecosyst 2014;17(1):63-70. [ Links ]

19. Franco-Guerra F, Gómez G, Villarreal-Espino OA, Camacho JC, Hernández J, Rodríguez EL, Marcito O. Bites rate on native vegetation by trashumance goats grazing in mountain rangeland in nudo mixteco, Mexico. Trop Subtrop Agroecosyst 2014;17(2):249-253. [ Links ]

20. Dávila P, Villaseñor JL, Medina R, Ramírez A, Salinas A, Sánchez-Ken J, Tenorio P. Listado Florístico del Valle de Tehuacán-Cuicatlán. Listados Florísticos VIII. Instituto de Biología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México; 1993. [ Links ]

21. Goetsch AL, Gipson TA, Askar AR, Puchala R. Feeding behavior of goats. J Anim Sci 2014;88(1)361-373. [ Links ]

22. Crawley MJ. The R Book. U.K: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. [ Links ]

23. Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Kindt R, Legendre P, O’Hara B, Simpson GL, Solymos P, Stevens MHH, Wagner H. vegan: Community ecology package. R package version 1.17-3; 2010. [ Links ]

24. R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org.; 2015. [ Links ]

25. Franco-Guerra F, Gómez G, Mendoza G, Barcena R, Ricalde R, Plata F, Hernández J. Influence of plant cover on dietary selection by goats in the Mixteca region of Oaxaca, Mexico. J Appl Anim Res 2005;27(2):95-100. [ Links ]

26. Sánchez CM, Gómez G, Álvarez M, Daza H, Garmendia J. Nutritional characterization of goat forage resources in extensive systems. Archivos Latinoamericano Prod Anim 2004;12(4):63-66. [ Links ]

27. Ramírez-Orduña R, Ramírez RG, Romero-Vadillo E, González-Rodríguez H, Armenta-Quintana JA, Ávalos-Castro R. Diet and nutrition of range goats on a sarcocaulescent shurbland from Baja California Sur, Mexico. Small Ruminant Res 2008;76(3):166-176. [ Links ]

28. Kronberg SL, Malechek JC. Relationships between nutrition and foraging behavior of free-ranging sheep and goats. J Animal Sci 1997;75(7):1756-1763. [ Links ]

29. Baraza E, Ángeles S, García A, Valiente-Banuet A. Nuevos recursos naturales como complemento de la dieta de caprinos durante la época seca en el Valle de Tehuacán, México. Interciencia 2008;33(12):891-896. [ Links ]

30. Kanani J, Lukefahr SD, Stanko RL. Evaluation of tropical forage legumes (Medical sativa, Dolichos lablab, Leucaena leucocephala and Desmanthus bicornutus) for growing goats. Small Ruminant Res 2006;65(1-2):1-7. [ Links ]

31. Andrade-Montemayor HM, Cordova-Torres AV, García-Gasca T, Kawas JR. Alternative foods for small ruminants in semiarid zones, the case of Mesquite (Prosopis laevigata) and Nopal (Opuntia sp). Small Ruminant Res 2011;98(1-3):83-92. [ Links ]

32. Darrell L, Rankins JR, Debra CR, Pugh DG. Feeding and Nutrition. In: Pugh DG, Baird NN editors. Sheep & goat medicine., Missouri: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012. [ Links ]

33. Landa-Becerra A, Mandujano S, Martínez-Cruz NS, López E. Análisis del contenido nutricional de plantas consumidas por caprinos en una localidad de la Cañada, Oaxaca. Trop Subtrop Agroecosyst 2016;19(3):295-304. [ Links ]

34. Lu CD, Kawas JR, Mahgoub, OG. Fibre digestion and utilization in goats. Small Ruminant Res 2005;60(1-2):45-52. [ Links ]

35. National Research Council (NRC). Nutrient Requirements of small ruminants: sheep, goats, cervids, and new world camelids. Washington, DC, USA. National Academy Press; 2007. [ Links ]

Received: February 18, 2017; Accepted: March 23, 2018

texto en

texto en