Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias pecuarias

On-line version ISSN 2448-6698Print version ISSN 2007-1124

Rev. mex. de cienc. pecuarias vol.7 n.2 Mérida Apr./Jun. 2016

Notas de investigación

Fermented feed elaborated with seeds of Canavalia ensiformis on growth and carcass of Pelibuey lambs

aColegio de Postgraduados, Campus Tabasco, 86500 Cárdenas, Tabasco, México.

bColegio de Postgraduados, Campus Montecillo, 56230 Montecillo, Estado de México, México.

cPráctica privada, Jalapa, Tabasco, México.

dInstituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, 86400 Huimanguillo, Tabasco, México.

The aim of this study was to determine the influence of a fermented food, made with Canavalia ensiformis seeds on growth performance and carcass characteristics of Pelibuey lambs (n=18). A completely randomized design with two-factor and repeated measures on a factor was used. The factors were the type of diet [unfermented food with canavalia (UFC), fermented food with canavalia (FC) and unfermented food without canavalia (UFWC)] and number of evaluation period. The variables evaluated were body weight (BW), average daily weight gain (ADG), average daily intake of dry matter, crude protein and metabolizable energy, as well as weight carcass and carcass yield. Type of diet, period number and type of diet x period number interaction affected (P<0.01) intake of all nutrients studied, BW and ADG. Type of diet affected (P<0.01) carcass weight. The FC diet allowed greater ADG (P<0.01) compared to UFC diet. Lambs fed with a diet UFWC had the highest ADG (P<0.05). In conclusion, lambs feeding diets containing canavalia seed meal allowed positive changes in growth and carcass weight; however, these changes were smaller in magnitude compared to those obtained with a diet without canavalia.

Key words: Fattening; Daily weight gain; Legume; Humid tropic

El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la influencia de un alimento fermentado, elaborado con semillas de Canavalia ensiformis, sobre el comportamiento productivo y características de la canal de ovinos Pelibuey (n= 18). El diseño utilizado fue completamente al azar con dos factores con medidas repetidas en un factor. Los factores fueron tipo de dieta [alimento sin fermentar con canavalia (SFC), alimento fermentado con canavalia (FC), alimento sin fermentar y sin canavalia (SFSC)] y número de periodo de evaluación. Se evaluó peso vivo (PV), ganancia diaria de peso (GDP), consumo diario de materia seca, proteína cruda y energía metabolizable, así como peso y rendimiento de la canal. El tipo de dieta, número de período y la interacción tipo de dieta x número de período afectaron (P<0.01) el consumo de todos los nutrimentos estudiados, PV y GDP. El tipo de dieta afectó (P<0.01) el peso de la canal. La dieta FC permitió una mayor GDP (P<0.01) con respecto a la dieta SFC. Los ovinos alimentados con la dieta SFSC fueron los que mostraron la mayor GDP (P<0.05). En conclusión, la alimentación de ovinos con dietas con harina de semillas de canavalia permitió cambios positivos en el crecimiento y peso de la canal. Sin embargo, estos cambios fueron de menor magnitud con respecto a los obtenidos con una dieta sin semillas de canavalia.

Palabras clave: Finalización; Ganancia diaria de peso; Leguminosa; Trópico húmedo

To elaborate diets for sheep, different ingredients are used, highlighting those that provide energy and protein, because these type of ingredients can have a high economic value for themselves, or because they have a significant percentage share in the diet composition.

In the specific case of the protein ingredients of vegetable origin, the tropical region of Mexico has edaphic and climatic conditions that allow the development of tropical leguminous, which produce seeds with a high potential to be incorporated into the diet of sheep. However, this type of seeds require complementary research to the already existing1-6, in order to facilitate its incorporation into various systems of sheep feeding in the tropical region.

In particular, the seeds of Canavalia ensiformis show content of metabolizable energy (ME) of 3.35 Mcal per kilogram of dry matter (DM)7, crude protein fluctuates between 22.8 and 35.3 % and the presence of starch between 24.7 and 36.9 %5,8. However, raw seeds of legume starch have a low digestibility, with respect to the starch from cereals and tubers9,10. Additionally, the seeds of canavalia have a variety of antinutritional factors (canavaline, concanavalin A and B, canavanine, canaline and tannins) that limit their inclusion in diets for monogastric and possibly also in ruminants1,5. In general terms the antinutritional factors present in the raw seeds of C. ensiformis reduce feed intake and its use for monogastric animals4,11.

Studies carried out with growing lambs1,12 indicated that 28 % of the meal from C. ensiformis seeds can safely be incorporated without health problems. However, the average daily gain (ADG) obtained with different levels of inclusion has been variable. Feed intake of male ovine with 30 % of meal from canavalia seeds reduces the ADG, with respet to 22 % (97 vs 127 g, respectively)1. In contrast, in another study12 with Pelibuey lambs the ADG was similar when feed contained 14 and 28 % of canavalia seeds. Additionally, there are no studies for evaluation of canavalia on the lamb carcass yield.

The use of canavalia seeds for feeding lambs has been done primarily with canavalia seeds flour. That is why it is necessary to assess whether the implementation of a technological process to the feed with raw seeds of canavalia allows to increase the efficiency of growing lambs. For example, when a feed is subjected to the process of solid-state fermentation increases as nutritious, and in the particularly case of a feed elaborated with raw seeds of canavalia is likely that this process will help to eliminate, reduce or inactivate antinutritional factors present in the canavalia seeds13,14,15. Based on this background, the objective of the study was to determine the influence of a feed fermented in solid state, made with C. ensiformis seeds as a source of protein, on the productive performance and carcass characteristics of Pelibuey lambs.

The study was conducted at the "El Rodeo" commercial farm, located in Jalapa, Tabasco, Mexico (17° 38' N, 92° 56' W). The climate of the region is warm humid with rains throughout the year (Af), the ambient average annual temperature of 25 °C and annual rainfall of 3,783 mm16. During the study the daily ambient temperature minimum and maximum (which occurred in 24 h) was measured with a thermometer type Six at 0800 h. With the data general averages and averages of periods of 14 d were calculated. The general averages of the minimum and maximum temperature were 21.01 ± 1.1 and 23.7 ± 2.3 °C. The duration of the study was 86 d and was divided in a pre-14-d phase and two experimental phases: growth (70 d) and carcass evaluation.

Growth study

The study used 18 Pelibuey lambs with an average age of 4 mo and a live weight of 21 ± 1.0 kg. They were randomly distributed to one of three treatments (six lambs per treatment). A completely randomized design was used with measures repeated in a factor17. The first factor was the type of diet [unfermented feed with canavalia (UFC), fermented feed with canavalia (FC), unfermented feed without canavalia (UFWC)]. The second factor was the number of evaluation period (five periods of 14 d to evaluate changes in live weight or 10 periods of seven days to evaluate changes in the nutrient intake). The experimental unit was the lamb. During the study, a lamb of the treatment without canavalia died by causes not related to treatments (pneumonia).

Lambs were individually fed throughout the study with isoenergetic and isoproteinic diets (Table 1). At the beginning of the study, each lamb received 500 g d-1 of feed according to the treatments. Subsequently, the amount was adjusted daily, based on the intake, trying to maintain at least 10 % of refused feed. The feed was offered from 0800 to 1800 h. Lambs had free access to water.

Table 1 Estimated composition of feeds made with canavalia in Pelibuey lambs during finishing phase

| Type of feed | |||

| UFC | FC | UFWC | |

| Canavalia seeds meal | 25.0 | 25.0 | 0.0 |

| Soybean meal | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.0 |

| Maize grain | 32.7 | 32.7 | 40.7 |

| Stylosanthes guianensis hay | 15.0 | 5.0 | 15.0 |

| GM 5 Brachiaria brizantha hay | 7.0 | 10.0 | 4.0 |

| Molasses | 15.0 | 10.0 | 15.0 |

| Vegetable oil | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Vitafer | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.0 |

| Amonium sulphate | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| Mineral salt | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Nutrients | |||

| Crude protein, % | 17.10 | 17.19 | 17.01 |

| ME, Mcal kg DM-1 (estimated) | 2.94 | 2.96 | 2.92 |

UFC= Unfermented feed with canavalia; FC= Fermented feed with canavalia; UFWC= Unfermented feed without canavalia.

The FC treatment included within its composition, meal of raw seeds of C. ensiformis; Vitafert (biologically active, rich in Lactobacilli and yeast, product obtained by liquid fermentation); soybean meal 4.0 %, rice polish 4.0 %, 15 %, mineral salt 0.5 molasses %, urea 0.4 %, 0.3 % ammonium sulfate, natural yoghurt 5.0 %, water 70.815 and subjected to the process of solid fermentation14 for a minimum of 10 d. UFC treatment was included as part of the meal of raw seeds of canavalia (this type of diet was only used with a maximum of 3 d of preparation).

The components determination in diets were: dry matter (DM), crude protein (CP), organic matter (OM)18; neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF)19in situ degradation of the DM (IDDM)20 and metabolizable energy (ME, Mcal kg DM-1)21. The IDDM of the three experimental diets was determined at 36 h in two hybrids bovines (Bos indicus x Bos taurus), castrated and provided with a rumen cannula, with an average weight of 500 kg, housed in individual pens with water and mineral salt at freedom. Animals adapted for 21 d with a ration based on grazing in a meadow mixed wi th humidicola pastures (Brachiaria humidicola) and camalote (Paspalum fasciculatum).

The variables evaluated in animals were: live weight (LW), average daily gain (ADG), DM daily feed intake (kg lamb-1), CP (g lamb-1), ME (Mcal lamb-1), NDF (g lamb-1), ADF (g lamb-1), as well as feed conversion rate (FCR) and feed efficiency (FE). Sheep were weighed by three consecutive days at 14 d intervals during six times. On each occasion, the average number of LW corresponded to the average weight of the three consecutive weightings. An electronic scale was used (Tru-Test Pro II version 3.2 ®), with an accuracy of 0.100 kg.

Feed intake by lamb was determined during three consecutive days every 7 d. Daily intake of DM, CP, ME, NDF and ADF was determined in 10 wk; for this it was considered the feed intake (humid basis) and the mean values of DM, CP, ME, NDF and ADF determined in ten samples (in duplicate) of each one of the experimental diets (Table 2). The FCR was determined through the DM intake:weight gain ratio. The FE corresponded to weight gain:DM intake relationship.

Table 2 Chemical composition of feeds elaborated with canavalia for finishing Pelibuey lambs

| Type of feed | |||

| UFC | FC | UFWC | |

| DM, % | 83.0 ± 1.2 a | 74.4 ± 0.8 b | 83.2 ± 1.0 a |

| CP, % | 16.2 ± 0.4 b | 17.1 ± 0.3 b | 18.8 ± 0.5 a |

| ME, Mcal kg DM-1 (estimated) | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| NDF, % | 30.6 ± 1.5 | 27.0 ± 1.0 | 29.4 ± 1.7 |

| ADF, % | 14.5 ± 1.2 | 12.3 ± 0.5 | 13.9 ± 0.9 |

| Ashes, % | 7.2 ± 0.4 | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 8.0 ± 0.6 |

| Organic matter, % | 92.8 ± 0.4 | 92.7 ± 0.5 | 92.0 ± 0.6 |

| IDDM, % | 77.2 ± 1.2 | 73.7 ± 1.2 | 78.0 ± 1.5 |

| n | 10 | 10 | 10 |

UFC= Unfermented feed with canavalia; FC= Fermented feed with canavalia; UFWC= Unfermented feed without canavalia. DM= Dry matter; CP= Crude protein; ME= Metabolizable energy; NDF= Neutral detergent fiber; ADF= Acid detergent fiber; IDDM= in situ degradation of dry matter after incubation for 36 h.

abValues with distinct superscript in rows are different (P<0.05).

Analysis of variance with the MIXED procedure was used(22)-I in the LW, ADG and DM intake CP, ME, NDF and ADF variables with support of the computer program23. Comparison of means was performed with the "t" test by square means using the SAS pdiff option. FCR and FE data were analyzed with the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-paired data23.

Carcass study

At the end of the growth stage all lambs were slaughtered at the Federal Inspection Slaughterhouse 51 in Villahermosa, Tabasco, Mexico. Carcasses were weighed and introduced (for 24 h) in a cooling chamber (0 to 4 °C). Commercial hot carcass yield (carcass weight/ slaughter weight x 100) was calculated. The Longissimus dorsi muscle area was measured in the cold carcass between the 12th and 13th rib vertebra by means of a square plastic film grid in centimeters24. Likewise, measured the distance of the greater diameter in middle lateral way (A) and the diameter in back-ventral direction (B)25. Cold carcass was divided into five primal cuts: neck, arm, thorax, abdomen and leg26.

The variables evaluated were: carcass weight hot and cold (kg), hot carcass yield (%), area, greater and lesser diameters of the L. dorsi muscle, fat (mm) and weight of the primal cuts (kg). Analysis of variance with the GLM procedure17 with support in a computer program was used for the data23. The comparison of means was performed with the "t" test by square means with the pdiff23. Carcass yield data were analyzed using the Kruskal Wallis test. When influence of treatment on the response variable was detected, it was applied the Wilcoxon rank sum test for non-paired data23.

The given chemical composition of the three experimental diets are shown in Table 2. The IDDM in the two canavalia diets was less than expected normally in sheep at 24 h (80 %)27 and 48 h (89 %)12, as well as lower than expected in cattle at 36 h (98.9 %)28. The differences between studies are probably attributed to the time used to determine the IDDM. There is evidence1 about a tendency to reduce the IDDM as the canavalia seeds level increases in the diet of sheep (62 % in diets containing 0 % of canavalia; 59 % with 22 % of canavalia and 57 % with 32 % of canavalia). IDDM values in FC and UFC diets are similar to the UFWC diet. This circumstance favors the use of canavalia as an ingredient for ruminants.

Feed and nutriments intake

Type of diet, number of period and their interaction affected (P<0.01) intake of all nutrients studied, but without difference in the intake level (P>0.05) due to feed fermentation. The higher increased nutrients intake (P<0.05) was detected in UFWC treatment (Table 3).

Table 3 Influence of fermentation in diets with Canavalia ensiformis seeds on nutrient intake of finishing Pelibuey lambs

| Type of diet | |||

| UFC | FC | UFWC | |

| Dry matter, g d-1 sheep-1 | 796 ± 60 a | 775 ± 60.0 a | 1,096 ± 66 b |

| CP, g d-1 sheep-1 | 129 ± 11 a | 132 ± 11.0 a | 206 ± 12 b |

| ME, Mcal kg DM-1 | 2.2 ± 0.16 a | 2.1 ± 0.16 a | 3.1 ± 0.18 b |

| NDF, g d-1 sheep-1 | 243 ± 17.0 a | 209 ± 17.0 a | 322 ± 18.6 b |

| ADF, g d-1 sheep-1 | 115 ± 7.9 a | 95 ± 7.9 a | 152 ± 8.7 b |

UFC= Unfermented feed with canavalia; FC= Fermented feed with canavalia; UFWC= Unfermented feed without canavalia; CP= Crude protein; NDF= Neutral detergent fiber; ADF= Acid detergent fiber.

ab Values with distinct superscript in rows are different (P<0.05).

Sheep fed FC and UFC diets showed a lower DM intake (and therefore of its components) in at least 27 % vs the UFWC diet. This result is not consistent with that reported in sheep1,12,29 where it was noted that the inclusion of canavalia seeds in levels from 10 to 32 % did not affect feed intake. On the other hand, there are not studies who evaluate the influence of the level of canavalia seeds meal in feedstuff for sheep on its palatability. Only, it has been suggested30 that canavalia shows low palatability when used as complement forage for sugar cane juice in comparison with other fiber sources (bran wheat, forage of sweet potatoes and Brachiaria decumbens). It is likely that lower DM intake detected in diets with canavalia seeds meal is attributed to a low palatability.

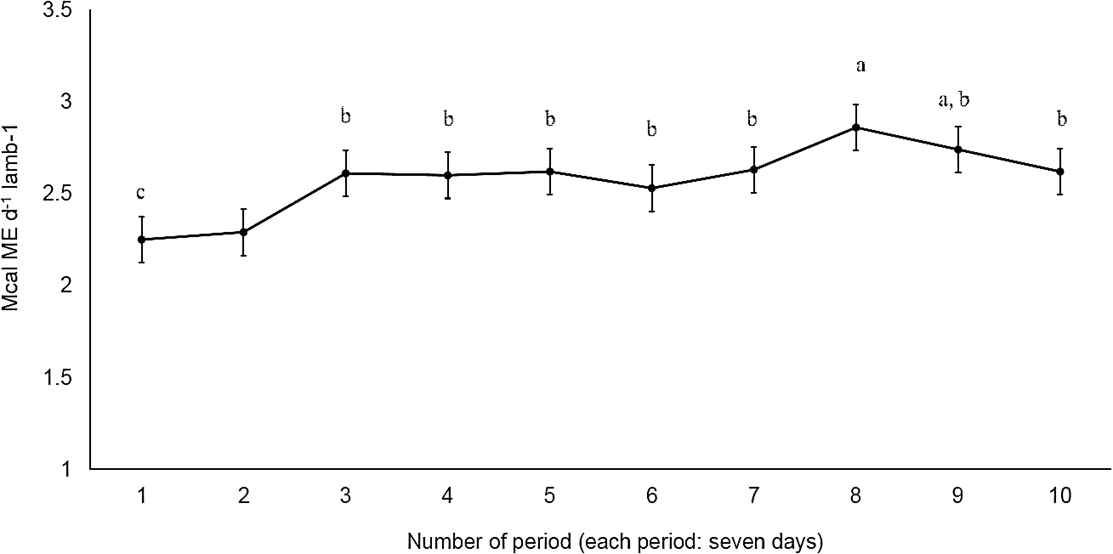

Intake of DM, ME, CP, NDF and ADF were influenced by the number of period (P<0.01). In particular, ME intake remained similar in the first two periods. Subsequently increased and remained almost constant in the rest of the periods, with the exception of the period 8 where increased to 2.8 Mcal d-1 lamb-1 (Figure 1).

abc (P<0.01)

Figure 1 Effect of number of period on metabolizables energy (ME) intake in finishing Pelibuey lambs

Intake of DM, CP, NDF and ADF considering the number of period, showed a similar trend as the DM. The increase in ME intake showed by lambs as the study advanced, was attributed to the type of diets used, who allowed to obtain a positive ADG and therefore the animals reached a higher LW. A higher LW increases DM and ME requirements31.

The interaction type of diet x number of period influenced (P<0.01) intake level of all nutrients studied. Lambs fed UFWC diet showed greater intake of DM, ME, CP, NDF and ADF through the entire period of study vs FC and UFC treatments.

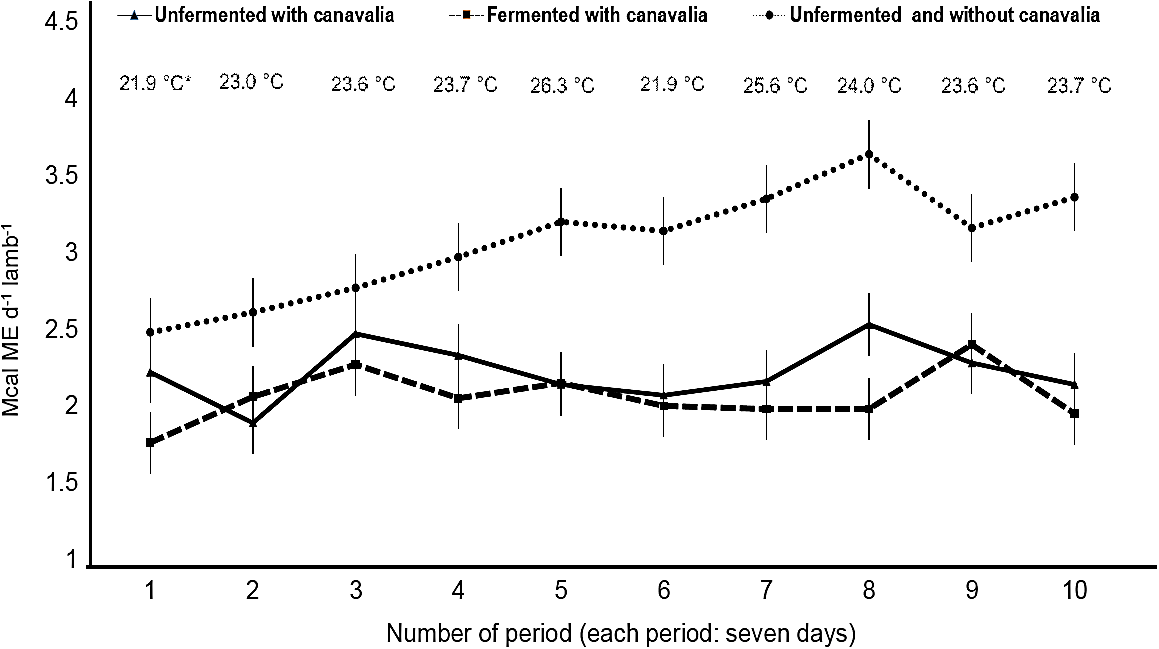

Figure 2 shows ME intake considering the type of diet and period number, as well as the values of maximum temperature in the shelter (average temperature in each period). Lambs in the UFWC treatment had higher ME intake during the entire period of study with respect to the FC and UFC treatments.

Least squares means (± standard error) (P<0.01). * Maximum shelter temperature.

Figure 2 Effect of fermentation and number of period on metabolizable energy intake in finishing Pelibuey lambs

In the UFWC treatment ME intake increased through the study, detecting the higher intake in the period 8. However, between the period 5 and 10 a steady ME intake with small variations was registered. The voluntary intake in the ruminant is affected by multiple factors, including physical (distension of the reticulum-rumen), hormonal (gastrointestinal hormones) and chemicals (volatile fatty acids)32.

It is likely that the higher maximum temperature recorded at the site where lambs stayed, limited ME intake (Figure 2). In this respect, it has been documented that an increase in temperature is associated with a reduction in feed intake33. Additionally, the digestibility value of a diet limits energy intake, when DM digestibility (in diet with high fiber content) is between 67 and 80 %, the DM intake decreases as digestibility is increased after adjusting for body weight and energy produced32. In the present study the IDDM of diet UFWC was greater than 67 %.

In several studies1,12 where canavalia seeds were evaluated in lambs, reported no changes in feed intake in intermediate periods of the study. However, in a work with sheep12 considering two stages of growth (15 to 24 kg and 24 to 28 kg), was detected an influence of the level of canavalia in the feed. Results that do not match with findings identified in this study, where the lambs of the UFWC treatment showed marked differences in ME intake, from the third period, to the end of the study vs FC and UFC diets. This may be due to the presence of anti-nutritional factors in the canavalia seeds, which could be related to reduction of DM intake. In this regard, it has been proposed34 that the ruminal medium is a place of detoxification of substances present in the feed for ruminants. However, it is possible that for the case of the antinutritional factors present in the canavalia seeds, the ruminal environment was not fully effective to minimize the negative effects of these factors.

With the exception of the period 8, ME intake in FC and UFC diets within the same period was similar (P>0.05). The above situation indicates that fermentation applied to the feed with canavalia did not affect intake of this type of diet.

Growth

Type of diet affected LW (P<0.05) and ADG (P<0.01) of lambs. The UFWC diet allowed a higher LW and ADG in relation to UFC and FC diets. The least squares means (± SE) were 29.9 ± 1.6 kg and 195 ± 14.6 g, 23.0 ± 1.6 kg and 62 ± 13.4 g, 24.4 ± 1.4 kg and 107 ± 13.4 g, respectively. ADG obtained in treatments with canavalia was less than that reported in other studies with sheep1,12. In Pelibuey males12 ADG varied between 190 and 220 g in animals fed with canavalia, while in diets where canavalia seeds meal replaced partially the soybean meal, the ADG was between 98 and 127 g1.

The lower ADG detected in FC and UFC diets can be attributed to lower DM intake compared to the UFWC diet, which meant an intake reduction of 32 and 37 % ME and CP respectively. In addition, it is important to consider that an increase in the level of canavalia seeds meal reduces digestibility of cell wall components; with canavalia levels of 0, 22, and 32 % digestibility values were 59, 58 and 48 %, respectively1. Some others agree35 that sheep fed with Pennisetum purpureum and a dietary supplement (cotton seeds meal or C. ensiformis seeds meal) fibrous DM digestibility was 20 % greater for the treatment with cotton seeds with respect to canavalia treatment. In the present study, the experimental diets had between 27.0 and 30.6 % of NDF, and it is likely that in FC and UFC diets the digestibility of the cell walls had been reduced with respect to UFWC, situation that could help to explain the lower ADG. On the other hand, application of the fermentation process to feed with canavalia favored a greater ADG compared to UFC diet. This indicates that fermentation increased feed efficiency, since DM intake was similar in diets with canavalia.

The number of period influenced (P<0.01) LW and ADG. The LW was increased from the period 1 to 5 (21.3 ± 0.9 to 29.1 ± 0.9 kg). However, there was no difference (P>0.05) during the periods 5 (29.1 ± 0.9) and 6 (29.4 ± 0.9). The largest ADG was recorded between periods 2 to 3 (164 ± 18 g) and 4 to 5 (165 ± 18 g) and the lowest in the last period of 5 to 6 (165 ± 18 g). The changes detected through time in LW and ADG agrees with a study conducted in Pelibuey sheep male36, who states that initially the production will have a fast growth as feed supply increases, then, it will be a point where the sheep weight will tend to decrease at unsatisfactory levels.

Additionally, when sheep achieved a feed intake level allowing to meet maintenance and growth requirements (measured through a positive ADG), the response is a sustained over time weight gain31,37,38. In this regard, it has been suggested31 that to obtain an ADG of 150 g, lambs with 20, 25 and 30 kg, should consume 2.7, 3.0 and 3.4 Mcal ME d-1, respectively. In the present study although the lambs showed lower ME daily intake, they achieved an ADG exceeding 150 g, likely attributed to the energy density of the diets used (Table 2), which was exceeding the recommendation for hair sheep31.

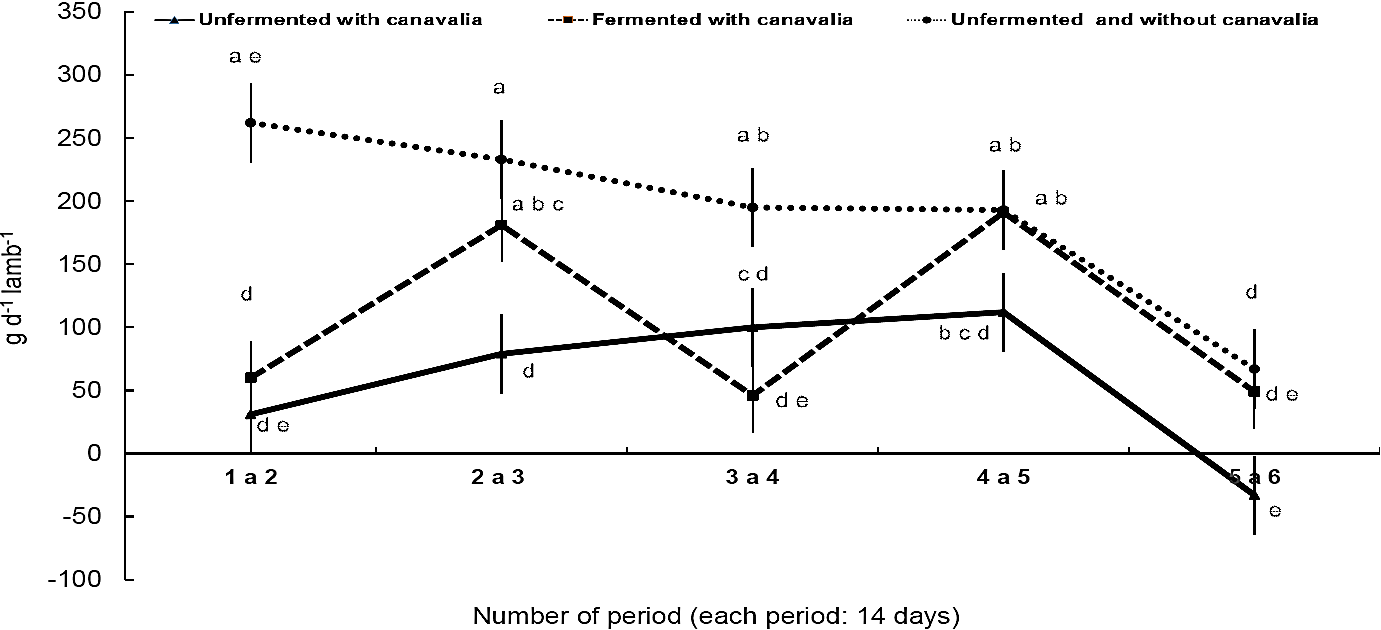

The interaction diet type x number of period affected (P<0.01) LW and ADG. Lambs in UFWC diet showed greater ADG at the beginning of the study (periods 1 to 2), and in the middle of the study (periods 3 to 4) with respect to FC and UFC diets (Figure 3). Sheep fed FC diet showed a greater ADG with respect to UFC diet only in period 2 to 3; ADG was similar in the other periods.

abc (P<0.01)

Figure 3 Effect of fermentation and period on average daily gain (ADG) in finishing Pelibuey lambs

With the exception of the last period, in the UFC diet, the ADG recorded throughout the study was positive. However, a tendency to reduce the ADG as the study advanced was detected in the three diets. This has been previously reported37 in Pelibuey sheep grazing and receiving a feed complement. In the present study, the lamb continued growing (increases in LW and positive ADG) through the study, regardless of the diet. However, the máximum weight of the lamb (when the weight of the animal is a function of time), did not represent the maximum biological efficiency, which is consistent with previously data described in Pelibuey lambs36.

The total ADG, FCR and FE were affected (P<0.05) by type of diet (Table 4). Although ADG was grater in lambs fed by the UFWC vs FC and UFC diets, AC and FE in the UFWC and FC treatments were similar (P>0.05). Lambs with the UFC diet showed the lower ADG and FE, as well as greater AC with respect to UFWC and FC diets.

Table 4 Least square means (± standard errors) of variables in Pelibuey lambs with diets based on Canavalia ensiformis sedes

| Variable | Type of diet | ||

| UFC | FC | UFWC | |

| Initial weight, kg | 21.0 ± 1.1 | 20.8 ± 1.1 | 22.2 ± 1.2 |

| Final weight, kg | 25.2 ± 1.7 a | 28.0 ± 1.7 a | 35.5 ± 1.8 b |

| ADG, g | 62.0 ± 13.4 a | 107.0 ± 13.4 b | 195.0 ± 14.6 c |

| FCR | 14.9 ± 3.16 a | 7.5 ± 0.59 b | 5.9 ± 0.36 b |

| FE | 0.079 ± 0.012 a | 0.137 ± 0.009 b | 0.173 ± 0.011 b |

| n | 6 | 6 | 5 |

UFC= Unfermented feed with canavalia; FC= Fermented feed with canavalia; UFWC= Unfermented feed without canavalia; ADG= Average daily gain; FCR= Feed convertion; FE= Feed efficiency.

abc Values with distinct superscript in rows are different (P<0.05).

AC obtained with UFWC diet was similar to those reported previously in Pelibuey lambs12 and lower to indicated in hair sheep1. However, the FCR in the UFC diet was higher than indicated by Dixon et al1 who showed a FCR of 8.9 and 10.8 for inclusion levels of canavalia of 22 and 32 %, respectively. For his part, Mamani12 reported a 7.2 AC when the canavalia was included in a 28.2 %. Apparently, the low DM intake and the smaller ADG detected in sheep fed UFC diet explains the high AC obtained. In support to this, there are indications that suggest that an increase in the level of raw canavalia seeds in sheep's feed tends to increase the weight of ruminal contents, and possibly reduce its change rate1.

It is likely that inclusion of canavalia seeds, affects not only the digestibility of the diet30 and the fibrous fraction of DM digestibility35, but that the various antinutritional factors (e.g., concanavalin A and canavanine) present in the seeds limit intake of this type of diet. It has been suggested that the lectin (concanavalin A is a lectin) present in C. ensiformis and in Phaseolus vulgaris reduces absorption of nutrients by joining the surface of the epithelial cells of the small intestine4. No studies were found that addressed the possible damage that causes the concanavalin A to the rumen epithelium. While in a study performed in vitro with canavanine39 was observed that this amino acid inhibits the growth of media of the lactic acid bacteria Lactobacillus arabinosus 175 (8014). The extent of the possible damage of canavanine to bacteria in the rumen will need to be addressed in future studies.

The results obtained in the intake of CP, ME, NDF and ADF, as well as the ADG, FCR and FE suggests that application of fermentation in solid state to canavalia diets allowed lambs to show higher growth efficiency in relation to UFC diet. It is suggested that this increased efficiency could be related to a reduction or inhibition of the negative effects of antinutritional factors present in the C. ensiformis seeds. Previous studies15 show that application of the fermentation process in solid state at the meal of raw C. ensiformis seeds reduces the canavanine concentration 12 % with respect to unfermented seeds, 3.7 vs 4.2 g 100 g DM-1, respectively.

Application of fermentation to feedstuffs with canavalia allowed to increase the productive efficiency of lambs compared to a diet without fermentation, situation that increases the possibilities to include canavalia seeds in finishing diets for sheep in tropical regions.

Carcass features

With the exception of the hot carcass yield and lower L. dorsi muscle diameter, the rest of the variables studied were affected (P<0.01) for the type of diet (Table 5). Lambs receiving the UFWC diet showed greater fat carcass weight and fat coverage, as well as greater weight of the five primal cuts vs FC and UFC diets. However, the area and the greater diameter of the L. dorsi muscle were similar in lambs fed UFWC and FC diets.

Table 5 Least square means (± standard errors) of post mortem variables in Pelibuey sheep fed with diets based on Canavalia ensiformis sedes

| Variable | Type of diet | ||

| UFC | FC | UFWC | |

| Slaughter weight, kg | 25.2 ± 1.7 a | 28.0 ± 1.7 a | 35.5 ± 1.8 b |

| Hot carcass weight, kg | 11.3 ± 0.8 a | 12.4 ± 0.8 a | 16.8 ± 0.9 b |

| Cold carcass weight, kg | 11.1 ± 0.8 a | 12.1 ± 0.8 a | 16.5 ± 0.9 b |

| Hot carcass yield, % | 44.7 ± 1.1 | 44.2 ± 1.1 | 47.4 ± 1.2 |

| Cold carcass measurements: | |||

| Longissimus dorsi área, cm2 | 9.3 ± 0.6 a | 10.7 ± 0.6 b | 12.5 ± 0.7 b |

| L. dorsi large diameter, cm2 | 4.8 ± 0.2 a | 5.2 ± 0.2 b | 5.8 ± 0.2 b |

| L. dorsi small diameter, cm2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 | 2.7 ± 0.2 |

| Fat, mm | 0.9 ± 0.4 a | 0.7 ± 0.4 a | 2.8 ± 0.4 b |

| Neck, kg | 1.1 ± 0.1 a | 1.0 ± 0.1 a | 1.6 ± 0.1 b |

| Chest, kg | 3.0 ± 0.3 a | 3.5 ± 0.3 a | 4.8 ± 0.3 b |

| Shoulder, kg* | 1.9 ± 0.1 a | 2.2 ± 0.1 a | 2.7 ± 0.1 b |

| Foreshank, kg | 2.4 ± 0.3 a | 2.8 ± 0.3 a | 3.8 ± 0.3 b |

| Leg, kg* | 2.6 ± 0.2 a | 2.6 ± 0.2 a | 3.5 ± 0.2 b |

| N | 6 | 6 | 5 |

UFC= Unfermented feed with canavalia; FC= Fermented feed with canavalia; UFWC= Unfermented feed without canavalia.

* Weight of both legs.

ab Values with distinct superscript in rows are different (P<0.05).

The carcass weight is important because it represents the economic value of the products obtained when lamb are slaughtered; the carcass weight of the FC and UFC diets represented the 73.8 % and 67.3 %, respectively, of the carcass weight of UFWC diet. This response can be explained, partially, by the increased ME intake that showed the lambs with the UFWC diet. Partida and Martinez42 mention that an increase in the energy level (from 2.6 to 2.9 Mcal ME kg DM-1) allows to get a heavier carcass in Pelibuey lamb.

In the present study the diets contained a similar ME level, however, lambs with UFWC diet showed greater daily ME intake.

The hot carcass yield was less than 50 % in all treatments, which is consistent with reports in Blackbelly40 and Pelibuey41 grazing with feed supplementation; and Pelibuey in confinement42. However, it was lower to intact43,44 and castrated24, Pelibuey fed indoors. Apparently, the carcass yield differences between studies can be attributed to breed, feeding system, diet energy density and slaughter weight.

The primal cuts weight were higher in lambs with UFWC diet. This type of response is attributed to the increased nutrients intake in UFWC, that favors a greater synthesis of muscle tissue. It has been suggested42 that the higher energy density in the diet promotes a steady increase in muscle tissue up to 44 kg of weight, after which decreases. In the present study the lambs with the UFWC diet showed a higher and consistent nutrient intake with respect to lambs fed diets that included canavalia, which explains the greater weight of their primal cuts.

The area and greater diameter of L. dorsi muscle were similar in diets UFWC and FC, probably due to the similar FE detected between these two diets. While lambs with UFC diet had lower values in both parameters, as well as a lower FE; the latter is an indicator of the ability of the animal to gain weight depending on feed intake.

With the exception of dry matter, solid state fermentation process did not alter the chemical composition of the diets that included canavalia. However, lambs fed diet fermented with canavalia obtained greater feed efficiency and daily weight gain with respect to those who consumed feed non-fermented with canavalia, which indicates that the application of this process to a feed with raw canavalia meal seeds allows to increase the efficiency of production of finishing lambs. The lambs fed with diet non-fermented and without canavalia, showed greater nutrient intake that favored better growth efficiency, as well as higher carcass weight. The addition of meal from canavalia seeds in finishing diets of lamb allowed positive changes in growth, weight and carcass composition. However, these changes were smaller with respect to those obtained in lambs fed with a diet without canavalia seeds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks to CONACYT for scholarship granted to the first author to perform his graduate studies within the Agro-food Production Program in the tropic, from the Colegio de Posgraduados, Campus Tabasco; and to Dr. José Manuel Pina Gutierrez, owner of El Rodeo farm by the facilities and partial funding of this research.

REFERENCES

1. Dixon RM, Escobar A, Montilla J, Viera J, Carabano J, Mora M, Risso J, et al. Canavalia ensiformis: A legume for the tropics. Recent advances in animal nutrition Conference Proc. Armidal, Australia. 1983:129-140. http://livestocklibrary.com.au/bitstream/handle/1234/19420/83_129.pdf?sequence=1 . Accessed 7 Sep, 2014. [ Links ]

2. Parra A, Combellas J, Dixon R. Rumen degradability of some tropical stuffs. Trop Anim Prod 1984; 9:196-199. [ Links ]

3. León R, Angulo I, Jaramillo M, Requena F, Calabrese H. Caracterización química y valor nutricional de granos de leguminosas tropicales para la alimentación de aves. Zootecnia Trop 1993; 11:151-170. [ Links ]

4. Ramos G, Frutos P, Giráldez FJ, Mantecón AR. Los compuestos secundarios de las plantas en la nutrición de los herbívoros. Arch Zoot 1998; 47:597-620. [ Links ]

5. Sridhar KR, Seena S. Nutricional and antinutricional significance of four unconventional legumes of the genus Canavalia - A Comparative study. Food Chemistry 2006; 99:267-288. [ Links ]

6. González LA, Hoedtke S, Castro S, Zeyner A. Evaluación de la ensilabilidad in vitro de granos de canavalia (Canvalia ensiformis) y vigna (Vigna unguiculata), solos o mezclados con granos de sorgo (Sorghum bicolor). Rev Cubana Cienc Agric 2012; 46:55-61. [ Links ]

7. Martin PC, Palma JM. Manual para fincas y ranchos ganaderos. Indicadores útiles para su manejo. Tablas tropicales de composición de alimentos. 1ra ed. Colima, México. Agrosystems Editing; 1999. [ Links ]

8. Sivoli L, Michelangeli C, Méndez A. Efecto combinado de la deshidratación en doble tambor y del tostado sobre la energía metabolizable verdadera y factores antinutrientes de harinas de Canavalia ensiformis. Zootecnia Trop 2004; 22:241-249. [ Links ]

9. Würsch P, Del Vedovo S, Koellreutter B. Cell structure and starch nature as key determinants of the digestion rate of starch in legume. Am J Clin Nutr 1986; 43:25-29. [ Links ]

10. Tovar J, Bjórck IM, Asp N-G. Incomplete digestion of legume starches in rats: A study of precooked flours containing retrograded and physically inaccessible starch fraction. J Nutr 1992; 122:1500-1507. [ Links ]

11. Cáceres O, González E, Delgado R. Canavalia ensiformis: leguminosa forrajera promisoria para la agricultura tropical. Pastos y Forrajes 1995; 18:107-119. [ Links ]

12. Mamani AV. Comportamiento productivo y económico de corderos en engorda con grano de Canavalia ensiformes como harina y pellet [tesis maestría]. Tabasco, México. Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco; 2013. [ Links ]

13. Valdivié M, Elías A. Posibilidades del grano de Canavalia ensiformis fermentado con caña (Sacchacanavalia) en pollos de ceba. Rev Cubana Cienc Agric 2006; 40:459-464. [ Links ]

14. Elías A , Aguilera L, Rodríguez Y, Herrera FR. Inclusión de niveles de harina de granos de Canavalia ensiformis en la fermentación de la caña de azúcar en estado sólido (Sacchacanavalia). Rev Cubana Cienc Agric 2009; 43:51-54. [ Links ]

15. Carrillo ED. Efecto de la extrusión y fermentación sólida en la concentración de canavanina de semillas de canavalia (Canavalia ensiformis L.) [tesis maestría]. Tabasco, México; Colegio de Postgraduados Campus Tabasco; 2014. [ Links ]

16. Ayuntamiento Constitucional Jalapa. Plan de contingencia municipal. Sistema estatal de protección civil. H. Ayuntamiento Constitucional Jalapa, Tabasco, México. 2010. http://www.transparenciajalapa.gob.mx/pdfs/PLAN%20MUNICIPAL%20DE%20CONTINGENCIAS%20 PROTECCION%20CIVILpdf Consultado 20 Oct, 2014. [ Links ]

17. Cody RP, Smith JK. Applied statistics and the SAS programming language. 3th ed. New York, USA. North-Holland, Elsevier Science Publishing Co., Inc.; 1991. [ Links ]

18. AOAC. Official Methods of analysis. 16th ed. Arlington, VA, USA: Association of Official Analytical Chemist. 1995. [ Links ]

19. Van Soest PJ, Robertson JB, Lewis BA. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J Dairy Sci 1991; 74:3583-3597. [ Links ]

20. Ørskov ER, Hovell DeB FD, Mould F. The use of the nylon bag technique for the evaluation of feedstuffs. Trop Anim Prod 1980; 5:195-213. [ Links ]

21. ARC. The nutrient requirements of farm livestock. Technical review. Farnham Royal, UK. Commonwealth Agr Res Bureau. CAB International Press. 1980. [ Links ]

22. Wang Z, Goonewardene LA. The use of MIXED models in the analysis of animal experiments with repeated measures data. Can J Anim Sci 2004; 84:1-11. [ Links ]

23. SAS. SAS User's Guide: Statistics (version 9.0 ed.) Cary, N.C. USA: SAS Inst. Inc. 2002. [ Links ]

24. García JA, Núñez-González FA, Rodriguez-Almeida FA, Prieto C, Molina-Domínguez NI. Calidad de la canal y de la carne de borregos Pelibuey castrados. Téc Pecu Méx 1998;36:225-232. [ Links ]

25. Partida JA, Braña D. Metodología para la evaluación de la canal ovina. Folleto Técnico No. 9. México. Centro Nacional de Investigación Disciplinaria en Fisiología Animal. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias. 2011. [ Links ]

26. Martínez AMM, Bores RF, Castellanos AF. Zoometría y predicción de la composición corporal de la borrega Pelibuey. Téc Pecu Méx 1987; 25:72-84. [ Links ]

27. Pacheco MA, Rivera J. Utilización del grano de Canavalia ensiformis en dietas para rumiantes. Primera reunión sobre la producción y utilización del grano de Canavalia ensiformis en sistemas pecuarios de Yucatán. Yucatán, México. Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. 1985. [ Links ]

28. González R. Degradación ruminal de harina de granos de dos variedades de canavalia (Canavalia ensiformis y Canavalia gladiata). Rev Cubana Cienc Agríc 2004; 38:53-56. [ Links ]

29. Domínguez-Bello MG, Stewart CS. Effects of feeding Canavalia ensiformis on the rumen flora of sheep, and of the toxic amino acid canavanine on rumen bacteria. System Appl Microbiol 1990; 13:388-393. [ Links ]

30. Hughes-Jones M, Encarnación C, Preston TR. Some dietary interactions of sugar cane juice and high protein supplements. Trop Anim Prod 1981; 6:271-278. [ Links ]

31. Castellanos AF. Requerimientos alimenticios del borrego Pelibuey. En: Castellanos AF , Arellano C editores. Tecnologías para la producción de ovejas tropicales. Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones, Forestales y Agropecuarias. Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Agricultura y Alimentación. Yucatán, México. 1989:78-90. [ Links ]

32. Grovum WL. Apetito, sapidez y control del consumo de alimentos. En: Church CD editor. El rumiante, fisiología digestiva y nutrición. 1ra ed. Zaragoza, España: Acribia, SA; 1993:225-241. [ Links ]

33. Young BA. Influencia del estrés ambiental sobre las necesidades nutritivas. En: Church CD editor. El rumiante fisiología digestiva y nutrición. 1ra ed. Zaragoza, España: Acribia, SA ; 1993:525-538. [ Links ]

34. Domínguez-Bello MG . Detoxification in the rumen. Ann Zootech 1996;45(Suppl):323-327. [ Links ]

35. Dixon RM , Mora M . Particulate matter breakdown and removal from the rumen in sheep given Elephant grass forage and concentrates. Trop Anim Prod 1983; 8:254-260. [ Links ]

36. Rebollar-Rebollar S, Hernández-Martínez J, Rojo-Rubio R, González-Razo FJ, Mejía-Hernández P, Cardoso-Jiménez D. Óptimos económicos en corderos Pelibuey engordados en corral. Universidad y Ciencia 2008; 24:67-73. [ Links ]

37. Oliva J, Vidal A. Utilización del zeranol en borregos Pelibuey en pastoreo y con concentrado energético. Universidad y Ciencia 2001;17:57-64. [ Links ]

38. Mora-Morelos H, Hinojosa-Cuéllar JA, Oliva-Hernández J. Características de crecimiento postdestete de borregos Pelibuey en pastoreo con suplemento alimenticio. Universidad y Ciencia 2003; 19:105-111. [ Links ]

39. Kihara H, Snell EE. Ethionine, and canavanine inhibitions by thienylalanine, growth: VII. Relation to peptides and bacterial. J Biol Chem 1955; 212:83-94. [ Links ]

40. Cantón JG, Velázquez A, Castellanos A. Body composition of pure and crossbred Blackbelly sheep. Small Ruminant Res 1992; 7:61-66. [ Links ]

41. Oliva J , Vidal A . Descripción de la composición corporal en ovinos Pelibuey en pastoreo con complementación alimenticia e implantados con zeranol. Investigación y Posgrado 2013; 3:9-12. [ Links ]

42. Partida PJA, Martínez RL. Composición corporal de corderos Pelibuey en función de la concentración energética de la dieta y del peso al sacrificio. Vet Méx 2010; 41:177-190. [ Links ]

43. Partida PJA , Braña VD, Martínez RL . Desempeño productivo y propiedades de la canal de ovinos Pelibuey y sus cruzas con Suffolk o Dorset. Téc Pecu Méx 2009; 47:313-322. [ Links ]

44. Macías-Cruz U, Álvarez-Valenzuela FD, Rodríguez-García J, Correa-Calderón A, Torrentera-Olivera NG, Molina-Ramírez L, Avendaño-Reyes L. Crecimiento y características de canal en corderos Pelibuey puros y cruzados F1 con razas Dorper y Katahdin en confinamiento. Arch Med Vet 2010; 42:147-154. [ Links ]

Received: February 27, 2015; Accepted: April 14, 2015

![Characterization of varieties of sideoats grama grass [Bouteloua curtipendula (Michx.) Torr.] recommended for rangeland restoration](/img/en/prev.gif)

text in

text in