Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias pecuarias

versión On-line ISSN 2448-6698versión impresa ISSN 2007-1124

Rev. mex. de cienc. pecuarias vol.6 no.4 Mérida oct./dic. 2015

Articles

Typology of cattle producers in the indigenous region XIV Tulijá-Tseltal-Cho´l of the state of Chiapas, México

a Unidad Académica Multidisciplinaria de Yajalón, Universidad Intercultural de Chiapas. Corral de Piedra número 2, Tel: 9611310295 , San Cristóbal de Las Casas, 29299, Chiapas, México. jorgevelazqueza@yahoo.com.mx.

In order to assess the type of producer underlying the socio-economic region XIV Tulijá-Tseltal-Chól in the state of Chiapas, Mexico, a study was made on a regional basis of production systems. Direct interviews with producers (317) of agricultural production units by wandering around the towns of this region are characterized by being formed of ethnic groups of Mayan origin (Tzeltal, Chol and Tsotsiles), with a strong presence of mestizos and European descent. Forty eight (48) variables that were preselected leaving 11 for analysis by multivariate analysis were explored. The results show four types of producers who share productive activities like supplying minerals and animal health campaigns, but different in other aspects such as education. Another shared aspect is the low level of technological development that seems to show the poor promotion of its use that could improve the productive capacity that apparently seems to be limited by the amount of land. It is concluded that the type described is feasible to be used as qualifiers and push forward the resources devoted to underpin regional production must contain differentiated policies and in turn generate appropriate modern technology, real application to geo-ecological conditions region and promoting the use of it to recognize biodiversity and sustainable production as part of development strategies.

Keywords: Typification; Productive system; Multivariate system

Con el objetivo de evaluar la tipología de productores en la región socio-económica XIV Tulijá-Tseltal-Chol en el estado de Chiapas, México se hizo un estudio con carácter regional de los sistemas productivos. Se utilizaron entrevistas directas con productores (317) de las unidades de producción agropecuaria, haciendo recorridos por los municipios de esta región que se caracterizan por estar formadas de etnias de origen mayense (Tseltales, Choles y Tsotsiles), con una fuerte presencia de mestizos y de descendientes de europeos. Se exploraron 48 variables que fueron preseleccionadas quedando 11 para su análisis por medio del análisis multivariado. Los resultados muestran que se pueden diferenciar cuatro tipos de productores que comparten actividades productivas, como dar sales minerales y participar en campañas zoosanitarias, pero, diferentes en otros aspectos como el nivel educativo. Otro aspecto compartido es el bajo nivel de desarrollo tecnológico que parece demostrar la escasa promoción de su uso que podría mejorar la capacidad productiva y que en apariencia parece estar limitado por la cantidad de terreno. Se concluye que la tipología descrita es factible de utilizarse como clasificación para comprender e impulsar que los recursos que se destinen para apuntalar la producción regional deben contener políticas diferenciadas, y a su vez generar tecnología moderna apropiada, de real aplicación a las condiciones geo-ecológicas de la región, así como la promoción del uso de la misma que reconozca la biodiversidad y la producción sustentable como parte de las estrategias de desarrollo.

Palabras clave: Tipología; Sistemas productivos; Análisis multivariado

Introduction

The socio-economic region XIV called Tulijá-TzeltanTseltal-Chol Cho´l north of Chiapas, in southern Mexico, is identified as one of the regions with the highest bio-cultural diversity of the Mexican southeast. This area brings together three ethnic groups TzeltanTseltal-Chol Cho´l and to a lesser extent TzotzilTsotsil that are conjoined with a mixture of mainly German culture of European descent that arrived in the late nineteenth century1, where they contributed to the formation of existing cattle production systems in the region. Moreover, the regional ecosystems can support a diversity of production systems, its foundations are centered in the mega diversity and biological heterogeneity - culture2,3, supporting multiple forms of technical and economic organization of production. The elements that make them up consist of unique qualities and features, product of the biocultural diversity of its components that interact and influence each other, originating a vast productive environment whose roots are possibly derived largely from concepts of the original Mesoamerican system itself4,5. However, in some respects they also share characteristics and properties that make them similar, their similarities allowing for grouping for different purposes, i.e. for determining the typology of producers. Although it must be recognized that in this region XIV little is known about the characteristics of the types of producers that work in these systems, thus it is essential as mentioned6 to know in detail the production situation by identifying patterns of production and their limiting factors.

One of the central premises of this study is to identify the different types of regional livestock producers from the analysis of socio-economic and financial indicators. This is accomplished by carrying out a systematic evaluation within a vision framework whereby solutions are found and designed that are appropriate for the conditions of each of the categories of producers, particularly small-scale farming systems, where economic access to financial resources for the implementation of viable projects present high costs7. The objective of this research was to analyze the different socioeconomic characteristics of production systems in the region XIV Tulijá- TzeltanTseltal-Chol Cho´l of Chiapas to determine the different types of cattle producers.

Materials and methods

The classification of types of farmers involved in cattle production systems in this region is shaped by recognizing the biodiversity of multiple components integrated in a dynamic of constant interaction in terms of time and space8. Therefore, considering that this variety and interaction of its components form systems with their own functions and arrangements, then the system can be best conceptualized in term of multivariate sets9. Thus, the application of a model to study and explore the several variables to facilitate observed structures and functions of the sets or groups derived therefrom, require that the data be managed through various techniques such as multivariate statistical analysis (MSA)10,11.

The analysis of the different variables to define the types of producers was carried out from November 2012 to May 2013. Tours were conducted in different rural lands in the municipalities of Salto de Agua, Tila, Tumbalá, Sabanilla, Yajalón, Chilón and Sitalá, Chiapas located between 16° 04’ and 17° 56’ N, and 90° 22’ and 92° 42’ W, at 19 to 1,413 m asl12. This was done in order to implement various surveys and collect socioeconomic and financial information from livestock producers.

This region is characterized as being comprised by people of Mayan ethnic origin, to the west dominated by TzeltanTseltal-Chol Cho´l in the southeast part and towards the northeast by Tzotzil Tsotsil people, with a strong presence of mestizo and European descendants particularly in Chilón, Yajalón, Tila and Salto de Agua12. It has 4,673 km2 and has several types of climate: in the lower parts where the water drains the climate is warm humid with rains all year, and in the highest parts of Tumbalá the climate is subhumid, with rains in the summer13. The main economic activities in the region are agriculture, livestock, forestry and tourism.

Interviews with 317 livestock producers selected randomly were applied; the total sample size available was that of 6,508 bovine animal producers based on census data of cattle population in the region14. A simple random sampling was used and each production unit (PU) was considered as an experimental unit and was represented by each producer. Sampling formula used was15:

Where: N= population size; d= precision (5%); n= sample size.

A total of 43 variables were studied and the data was organized, systematized and analyzed using various multivariate techniques. The detailed study of the original variables resulted in a selection of 11 variables that were considered most important economically and productively for their contribution to a better analysis of the technological and social components used in the PU. The selected were subjected to a factorial analysis or a dimensional reduction16, to be summarized and explained with information that contained the full set of observed variables; identifying as appropriate, a smaller number of unobserved variables, called factors. The first statistical tests helped to confirm the 11 original variables that were analyzed by principal component analysis (PCA), and then later by cluster analysis, this permitted identifying the different types of producers17. The variables studied were, age and level of education of producers, total hectares and cattle area, animal heads and units, income (other income such as complementary professional activities, like employment, etc. were not considered, but only those deriving from livestock rearing), participation in animal health campaigns, equipment, infrastructure and application of mineral salts.

For the analysis of the variables, Pearson’s correlation was applied and then descriptive statistics were used to standardize the variables, KMO and Bartlett test were especially useful to define the degree of standardization18. Later PCA method was used to obtain the commonalities and test the total variance that recognized the minimum number of components that could confirm the contribution of variables in order to explain the different types. Matrix components as well as the rotation method by using Varimax with Kaiser Normalization. Later cluster analysis with Ward was done, in order to lastly carry out frequency testing. The first allowed for the reduction of information and identified the variables that explain the system, the second revealed data concentrations for efficient clustering and classified production systems by identifying the major differences between types of producers. Analyses were performed using the PSPP program version 1919.

Results

The analysis of the variables showed that the selected variables are closely correlated (Table 1), while the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.822 indicating that the factor analysis is appropriate because the resulting value match better with higher number of samples. The Bartlett test of sphericity and the approximate chi-square was highly significant (P=0.001), which confirms the correlation between variables and therefore the applicability of factorial analysis. The reduction process factors allowed for visualization of the behavior of the variables and identified four factors that can be grouped. Table 2 shows the commonalities, which expose the proportion of variance explained by the common factors into one variable, while in Table 3 the variances for each variable that account for 70 % of the variability of the original variables are shown.

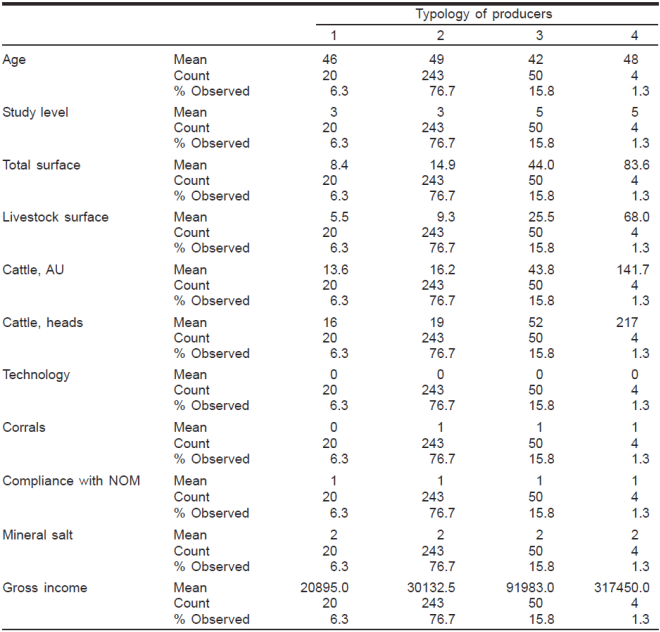

Table 1 Descriptive statistical analysis of the variables studied for the analysis of components of types of producers in region XIV Tulijá-Tzeltan-Cho’l.

NOM= Mexican oficial standards.

Table 3 Total explained variance of the variables analyzed.

ESL= Extraction sums of squared loading.

RSL= Rotation sums of squared loading.

The results of the analysis of the variables and their grouping can be seen in Table 4 and Figure 1. Four groups or types are formed with the following characteristics:

Table 4 Summary of variables and their contribution to the type observed in the region XIV Tulijá-Tzeltan-Cho’l in Chiapas, Mexico.

NOM= Mexican oficial standards.

Type I

This group is characterized by having a mean total area of 8.4 ha of which 5.5 ha are for livestock activities, which is equivalent to 13.6 animal units, with an average of 16 heads of cattle. They do not have technology for livestock production, such as mills or choppers or even corrals to manage, although they meet with Mexican official standards which includes national vaccination campaign against tuberculosis, brucellosis and rabies. The average age is 46 yr old and have on average a low level of schooling, since the resulting average is a completed elementary education (position 3), although the range varies from uneducated (position 1) to unfinished secondary schooling (position 4). The level of gross income from livestock (understood as the value of livestock sales, which is not really its liquid or available to the family income, because it is the value of sales includes production costs) is $20,895, with income per hectare of $ 3,778. In this group, 6.3 % of producers may be classified as very low income, and that the level of gross income combined with the number of animals involved in the production, the amount of land available for livestock and the apparent absence of appropriate technology is appropriate for this classification.

Type II

The total area is 14.9 ha for an availability of 9.3 ha for livestock. They have an average of 19 heads that are equivalent to 16.2 animal units, they have no modern technology or although they manage corrals. They comply with the animal health requirements and provide minerals. Annual revenues for livestock activities are on average $30,132. This grouping has an average age of 49 yr and an average level of study of a completed elementary education (position 3), although the range indicates that some have also attended university (position 7). Significantly, in this group there is the largest number of participants involved in productive units, with an average of 76.7 % of the total. Although reminiscent of the first group these could be classified as low-income producers, considering that the level of gross income together with the amount of livestock and livestock area is a little higher than the previous. However, when income is applied per hectare, they have the lowest income ($ 3,242) of all groups, although in this grouping there is a better technological level. This typology highlights its importance due to number of concentrated units located therein, and that they should, similar to the prior type, look for assistance and other strategies to help support their development.

Type III

They have a cattle area of 25.5 ha for a total area of 44 ha. An average of 52 heads or 43.8 animal units. They have corrals and they participate in animal health campaigns, besides providing mineral salts; however, they lack modern technology. The gross income is $ 91,983 and they participate by having 15.8 % of all production units. Here income per hectare is also recorded but it is not different from the other groups ($ 3,607). The age of farmers is 42 yr and has a secondary level of schooling completed (position 5). These characteristics point to a sector with higher levels of gross income, where the educational level is higher, because the range considered an education level where high school was completed (position 6), or even university (position 7). It is a group that can be ranked as growing but is necessary to point out that they need better use of technological developments and improved infrastructure.

Type IV

Has a total area of 83.6 ha and 68 ha are intended for livestock activities. An average of 141.7 animal units representing 217 head of cattle. It can be seen that this grouping does not use modern equipment for production, although they comply with the official standards of animal health, including the right proportion of mineral salts. This group has the lowest share of livestock production units with 1.3 % of the total, although they have a higher income $317,450. However, it is noteworthy that the income per hectare is only slightly different from the other groups, as they have an income of $4,668.38. Those involved here have an average age of 48 yr and an average level of study corresponding to a completed secondary education (position 4). However, the maximum and range indicate that they have university level studies (level 7), which is higher than the first two groups, but like the third group. This group has the highest level of development in this region, considering their income, education and demonstrated productive capacity of the areas and the number of animals involved. However, they are limited by the amount of productive units that can participate and poor technological development, although the level of livestock infrastructure is better than the rest, it is not sufficient for the level of typology exhibited.

Discussion

The analysis of the results are reminiscent of those found by other authors, where they also used similar variables to those proposed here and were able to establish an acceptable level of standardization and correlation of their variables, were they also classified four types of producers7,20. Similar results are observed for the area of extension used for livestock activities; but differences in levels of technological development and arrangement of heads per hectare were found7.

This situation may be because the producers of the study region have not adopted the conscious use of modern sustainable technology strategies that are more appropriate to the region and that are useful in bolstering production.

It is important to point out that a variable that the statistical analysis in this study did not consider was production costs. It was not considered because over 70 % of respondents did not provide information; it’s probably because they do not keep or use records, so therefore they do not know their actual production costs, i.e. how much it costs to produce each unit of output, and thus do not know their profit or loss per unit of output. Consequently, their management capabilities are extremely low.

In sum, the region XIV Tulijá-Tzeltan-Cho’l have four profiles types of clearly defined producers, even if they share similarities in some productive activities as the proportion of minerals and participation in animal health campaigns, they are different in some others. Such as educational level that can be seen as a very important difference considering that the range in the first group includes even people without studies, while in the fourth group it includes individuals with higher studies even at the university level.

Another important aspect that is shared by all groups is the low level of technological development. This is alarming as it seems to demonstrate a lack of appreciation of the importance of their use, but one should also take into account the little gross income of most production units is probably impacting the lack of motivation for using modern technology. The application of appropriate technology to the geo-ecological conditions of the region could improve the productive capacity and increase the amount of cattle for production, which apparently seems to be limited by the amount of land. However, the use of modern, sustainable and appropriate technology could help remedy this aspect, even with type I that do not even have corrals for livestock management.

Conclusions and implications

Due to its characteristics, the four types observed and described imply that it is feasible to use this classification to understand and support the resources devoted to bolster livestock production. These must also have specific policies that promote the use of appropriate modern technology, with real applications suitable to the geo-ecological conditions of the region, while also recognizing biodiversity and sustainable production as part of its development strategies.

Literatura citada

1. De Vos J. Oro verde, la conquista de la selva lacandona por madereros tabasqueños, 1822-1949. 1ª ed. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica; 1988. [ Links ]

2. Boege SE. Centros de origen, pueblos indígenas y diversificación del maíz. Ciencias 2008;(92-93):18-28. [ Links ]

3. Viqueira JP. La comunidad india en México en los estudios antropológicos e históricos. Viqueira JP, Ruz MH. editores. Chiapas: Los rumbos de otra historia. 3ª ed. México: Centro de Estudios Superiores de México y Centroamérica; 1995. [ Links ]

4. Boege SE. Territorio y diversidad biológica, la agrobiodiversidad de los pueblos indígenas de México. En: Biodiversidad y conocimiento tradicional en la sociedad rural. México: Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable y Soberanía Alimentaria. 2006:237-298. [ Links ]

5. Carrillo TC. El origen del maíz. Naturaleza y cultura en Mesoamérica. Ciencias 2008;(92-93):4-14. [ Links ]

6. Vilaboa AJ, Díaz RP, Ruiz RO, Platas RD, González MS, Juárez LF. Caracterización socioeconómica y tecnológica de los agro-ecosistemas con bovinos de doble propósito de la región de Papaloapan Veracruz, México. Trop Subtrop Agroecos 2009;10(1):53-62. [ Links ]

7. Espinosa OA, Álvarez MA, Del Valle MC, Chauvette M. La economía de los sistemas campesinos de producción de leche en el Estado de México. Téc Pecu Méx 2005;43(1):39-56. [ Links ]

8. Escobar G, Berdegué J. Metodología para la tipificación de sistemas de finca. Escobar G, Berdegué J editores. Tipificación de sistemas de producción agrícola. Chile: Red Internacional de Metodología e Investigación de Sistemas de Producción (RIMISP); 1990:13-44. [ Links ]

9. Valerio CD, Acero CR, Perea JM, García MA, Castaldo A, Peinado J. Metodología para la caracterización y tipificación de sistemas ganaderos. Anim Gestión 2004;(1):1-9. [ Links ]

10. Hart RD. Agroecosistemas: conceptos básicos. 1ª ed. Turrialba, Costa Rica: Centro Agronómico Tropical de Investigación y Enseñanza; 1980. [ Links ]

11. Rodríguez QP. Sistemas de producción, conceptos y métodos de aplicación. En: Curso de especialización en interpretación de imágenes de sensores remotos aplicada a levantamientos rurales. Colombia: Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi (IGAC); 1993;40-69. [ Links ]

12. CEIEG. Comité Estatal de Información Estatal de Información Estadística y Geografía. Caracterización de las Regiones de Chiapas. México. 2013. http://www.ceieg.chiapas.gob.mx/home/?cat=207 y en: http://www.chiapas.gob.mx/gobiernosmunicipales/regiones. [ Links ]

13. Parra VMR. The agricultural sub development in the highlands of Chiapas. 1a ed. México: CIES-UACH Collection University Notebooks. 1989. [ Links ]

14. INEGI. Censo Agrícola, Ganadero y Forestal. México. 2007. http://www.inegi.org.mx/prod_serv/contenidos/espanol/bvinegi/productos/censos/agropecuario/2007/panora_agrop/chis/Panagrochis1.pdf. [ Links ]

15. Hernández SP, Fernández CC, Baptista LC. Metodología de la Investigación, 2ª ed. México: Mc Graw Hill; 2001. [ Links ]

16. Morrison DE. Multivariate statistical methods. 2ª ed. USA: McGraw Hill Book Company; 1976. [ Links ]

17. Jhonson DE. Métodos multivariados aplicados al análisis de datos. 2ª ed. México: International Thomson Editores; 2000. [ Links ]

18. Ruiz M, Ruiz J, Torres V, Cach J. Estudio de sistemas de producción de carne bovina en un municipio del estado de Hidalgo, México. Rev Ciencia Agríc 2012;46(3):261-265. [ Links ]

19. SPSS. User’s Guide: Statistics (version 19). NY, USA: SPSS Inc. 2010. [ Links ]

20. Leos RJ, Serrano PA, Salas GJ, Ramírez MP, Sagarnaga VM. Caracterización de ganaderos y unidades de producción pecuaria beneficiarios del Programa de estímulos a la productividad ganadera (PROGAN) en México. Agric Soc Des 2008;5(2):213-230. [ Links ]

Received: January 22, 2014; Accepted: March 03, 2015

texto en

texto en