Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO

Compartir

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versión impresa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 no.8 Texcoco nov./dic. 2017

https://doi.org/10.29312/remexca.v8i8.707

Articles

Diagnosis of the current situation of white mango flake

1Campo Experimental Iguala-INIFAP. Carretera Iguala-Tuxpan km 2.5, Col. Centro Tuxpan, Iguala de la Independencia Guerrero, México. CP. 40000.

2Campo Experimental Santiago Ixcuintla-INIFAP. Carretera México-Nogales km 6, Santiago Ixcuintla, Nayarit, México. AP. 100. CP. 63300.

3Campo Experimental Rosario Izapa-INIFAP. Tuxtla Chico, Chiapas, México. CP. 30780.

The mango is the most important socio-economic fruit tree in the state of Guerrero. The mango white scale (EBM), Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead, is an emerging pest of economic importance in Mexico, because it damages the foliage and branches of mango trees, as well as the appearance of fruits destined for export and the national market. The objective of the study was to know the distribution and intensity of infestation of the pest in the different mango cultivars of the producing regions of the state of Guerrero, which is important to implement control measures. During the 2012-2013 and 2013-2014 sampling cycles, significant differences were found in the abundance of A. tubercularis populations among the different mango producing areas. The EBM was found in the Costa Grande, Acapulco and Costa Chica regions, which make up the largest production area in the state. In the regions of Tierra Caliente and Norte there were no indications of the presence of the pest. The municipalities with the highest incidence were San Jeronimo with 2.91 total EBM/sheet, followed by Juchitan, Marquelia and Tecpan de Galeana, with an average of 1.25, 1.23 and 1.23 individuals/sheet respectively. The cultivar that registered the highest presence of white scale was Manila, followed by Ataulfo, Tommy Atkings and Haden, and in lesser quantity Kent and the so-called Creole.

Keywords: Aulacaspis tubercularis; distribution; mango; Guerrero

El mango es el frutal de mayor importancia socioeconómica del estado de Guerrero. La escama blanca del mango (EBM), Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead, es una plaga emergente de importancia económica en México, debido a que daña el follaje y ramas de árboles de mango, así como la apariencia de frutos destinados a exportación y mercado nacional. El objetivo del estudio fue conocer la distribución e intensidad de infestación de la plaga en los diferentes cultivares de mango de las regiones productoras del estado de Guerrero, lo cual es importante para implementar medidas de control. Durante los ciclos 2012-2013 y 2013-2014 de muestreo se encontraron diferencias significativas en la abundancia de las poblaciones de A. tubercularis entre las distintas áreas productoras de mango. La EBM se encontró en las regiones de la Costa Grande, Acapulco y la Costa Chica, las cuales conforman el área de mayor producción del estado. En las regiones de Tierra Caliente y Norte no se encontraron indicios de la presencia de la plaga. Los municipios con mayor incidencia fueron San Jerónimo con 2.91 total EBM/hoja, seguido por Juchitán, Marquelia y Tecpan de Galeana, con un promedio de 1.25, 1.23 y 1.23 individuos/hoja respectivamente. El cultivar que registró mayor presencia de escama blanca fueron Manila, seguido por Ataulfo, Tommy Atkings y Haden, y en menor cantidad Kent y el denominado criollo.

Palabras claves: Aulacaspis tubercularis; mango; distribución; Guerrero

Introduction

In Mexico, 191 016 hectares of mango (Mangifera indica L.) are cultivated and more than 1.78 million tons of fruit are produced, with a value higher than the $5.44 billion Mexican pesos. Guerrero is the main mango producing state, contributing 20% of the national production with 25 307 ha, with average yields of 15.5 t ha-1 (SIAP, 2016). The regions with the highest production and planted area are Costa Grande, Costa Chica and Tierra Caliente, where the Manila cultivar predominates with 33% of the surface, followed by ‘Ataulfo’, Haden, Creoles, Tommy Atkins, and Kent with 30, 16, 14, 05 and 01% respectively (SIAP, 2016). About 7 000 rural producers depend on the mango productive chain, and indirectly: suppliers, contractors and day laborers (RDS, 2003).

Mango in Guerrero faces several phytosanitary problems, among which is an emerging plague of recent economic importance, mango white scale (EBM), Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead (Hemiptera: Diaspididae), registered in 2003 for the first time in mango orchards of the municipality of Compostela, Nayarit, Mexico. Later, it was dispersed to other producing areas of Nayarit, in which it affected approximately 10 thousand ha (Urias, 2006; García- Álvarez et al., 2014), currently it is distributed in other states of Mexico.

The female of A. tubercularis is oval, flat and transparent white in color, it is located on both the leaves of the upper and lower back (Peña and Mohyuddin, 1997, Moharum, 2012) and on the surface of the fruits (Urias and Flores, 2005; Urías-López et al., 2010). When populations of A. tubercularis nymphs are high, it causes leaf fall and branch death (Hodges et al., 2005). However, the EBM colonies cause the greatest economic damage due to the chlorotic spots that cause on the surface of the fruits, a condition that deserves its quality for export, since there are reports of 50% of fruits rejected by packers (Hodges et al., 2005; Isiordia-Aquino et al., 2011; Juárez-Hernández, 2014).

The temporary abundance of EBM in Guerrero has two population increases, the first between may to august and the other increase from december to february; this plague although it occurs in all the branches of the trees oriented towards the four cardinal points, the populations are more abundant in the south and north sides; In addition, it was found that temperature and wind correlate positively with greater abundance of scales, while precipitation and relative humidity correlate negatively (Noriega et al., 2016).

Due to the increases in the infested area and the density of the EBM populations in recent years in Guerrero, greater knowledge of the affected areas and the degree of infestation is required for decision making in their control. Therefore, the objective of this work was to generate information on the distribution and intensity of infestation of the pest in the different mango cultivars in the producing regions of the state of Guerrero.

Materials and methods

Study area. The state of Guerrero is located between 16°18’ and 18°48’ north latitude and between 98°03’ and 102°12’ west longitude. The predominant climate is warm sub-humid Aw (63.94%), followed by semi-warm sub-humid (A)C(w) (20.99%) mainly (García, 2004; INEGI, 2016). In the first (Aw), the main mango producing areas are located at altitudes of 0 to 750 m.

Sampling. To determine the distribution of EBM in the state, from 2012-2013 to 2013-2014, different commercial mango orchards were sampled from the main producing areas of the state, using the parcel registry of the State Council of Mango in Guerrero. Due to the extension of the production area, it was divided into six regions, Tierra Caliente, Norte, Centro, Acapulco, Costa Grande and Costa Chica, whose delimitation was considered by municipality and localities. In each locality, orchards with an area of one hectare were selected for sampling.

In each orchard a single sampling was carried out, during the period of greatest pest population abundance, from the growth of the fruits to the harvest (January to May) of each production cycle. The sampling was carried out in the main mango cultivars, Manila, ‘Ataulfo’, Tommy Atkins, Haden, Kent and the so-called Creole. For this, the methodology suggested by Urías-López et al. (2010), which consists of selecting five trees per orchard taking into account the size, age and uniform appearance; in each tree four branches are marked oriented to the cardinal points. From each branch, two leaves were selected from the middle part of the internode, from the penultimate seasonal vegetative flow. On both sides of each leaf, a count of females and colonies (males) of the scale was made.

The percentage of fruits infested was also considered, so that four shoots with the presence of fruits were selected at random. In all the fruits of each selected shoot, the presence of females and scale colonies was determined. The calculation of the percentage of fruits infested was made considering the presence of fruits with the presence of any biological state and the free fruits of the pest. As characteristics of the orchards, data such were recorded as the variety, height above sea level and the age of the orchard (more or less than 10 years).

In the first production cycle 2012-2013, 46 commercial orchards were sampled, located in 42 locations of the main mango producing municipalities in the state. In Tecpan de Galeana, nine orchards were sampled, in Cuanjinicuilapa (eight orchards), in Coyuca of Benítez (four orchards), in Atoyac of Alvarez, Acapulco, Florencio Villareal, Juchitan and Marquelia (three orchards/municipality), in Iguala, Benito Juárez and Arcelia (two orchards/municipality), Juan R. Escudero, Copala, Tepecoacuilco and Cutzamala (an orchard/Municipality).

In the second cycle 2013-2014 the 61 commercial orchards were sampled, located in 42 towns of the municipalities of: Tecpan of Galeana (13 orchards), in the Union of Isidoro Montes of Oca (12 orchards), Petatlan (nine orchards), Atoyac and Jose Azueta (six orchards/municipality), Cuajinicuilapa (five orchards), Marquelia and Coyuca of Benítez (three orchards/municipality) and Florencio Villareal (two orchards).

Database. Each sampled orchard was georeferenced with GPS, thus forming a unified database. For the elaboration of the cartography, the geographic information system Arc Map 10 was used, as well as the digital elevation model of INEGI, the layers of state political division, bathymetry and border states of CONABIO, the parcel pattern of SAGARPA. Similarly, as indicated by SINAVEF (2010), the cartographic presentation was standardized in order to make the information more readable, clear and attractive to the user.

The main source of information to identify the geographical distribution of mango producing areas in Mexico was the parcel census, which issues a real pattern of plots in the field. This pattern was obtained by direct measurement in the parcels of the producers, by means of crews with GPS equipment; unlike the surfaces reported by SAGARPA itself via the SIAP, which are estimated from interviews with the producers and therefore reflect only the reported area.

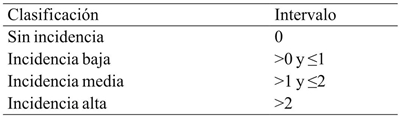

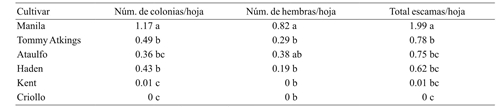

The mapping of the geographic spatial distribution of the EBM, was elaborated from sampling in commercial orchards with the presence of females, colonies and both (total) by leaf and by fruit. To know the incidence by orchard, the data were averaged by leaf, branch and tree, classifying the incidence according to Table 1.

Statistic analysis. Analysis of variance of the variables under study (population density of the colonies, females and total EBM for the localities, municipalities and cultivars) was carried out, by means of a random block design with five repetitions, considering each tree as repetition. To compare the Tukey test (p<0.05), the analyzes were performed with the SAS program (SAS, 2010).

Results and discussion

Distribution by location. The presence of EBM was detected in some localities of the state of Guerrero (Table 2), where fourteen localities with high incidence are observed, with values of 2.91 to 1.23 total scales/leaf, with significant differences among several localities (p≤ 0.05) ; for example, San Jeronimo, Municipality of Benito Juárez showed 2.91 total scales/sheet followed by 4 locations of Tecpan of Galeana, three of The Union I. M. of Oca, two of the Juchitan and one of Florencio Villareal, Marquelia, Petatlan and Coyuca of Benítez. An average incidence was observed in thirteen localities, with 1.04 to 0.45 total scales/leaf, with significant differences (p≤ 0.05); three localities belonging to the Municipality of Cuajinicuilapa and the others to a locality for each of the 12 municipalities of the Costa Chica and Grande regions of the state. A low incidence was observed in sixteen localities with 0.41 to 0.03 total scales/leaf, where the statistical test did not detect significant difference, in 12 localities of six municipalities of the Costa Grande region and two Municipality localities of Cuajinicuilapa and one of Marquelia.

Table 2 Geographic distribution of white flake (EBM) of mango leaves by location in Guerrero, 2012-2014.

Las medias en cada columna con letras distintas son significativamente diferentes (Tukey, p≤ 0.05).

Finally, without incidence, four localities of Petatlan and Cuajinicuilapa were observed, as well as three locations of Tecpan of Galeana and The Union of Isidoro Montes of Oca; two localities of Juan R. Escudero, Iguala, Arcelia and Cutzamala and a locality in Copala, Marquelia, Tepecoacuilco and José Azueta with zero scale values, where the statistical test did not detect significant differences between localities that are in intermediate and low incidence.

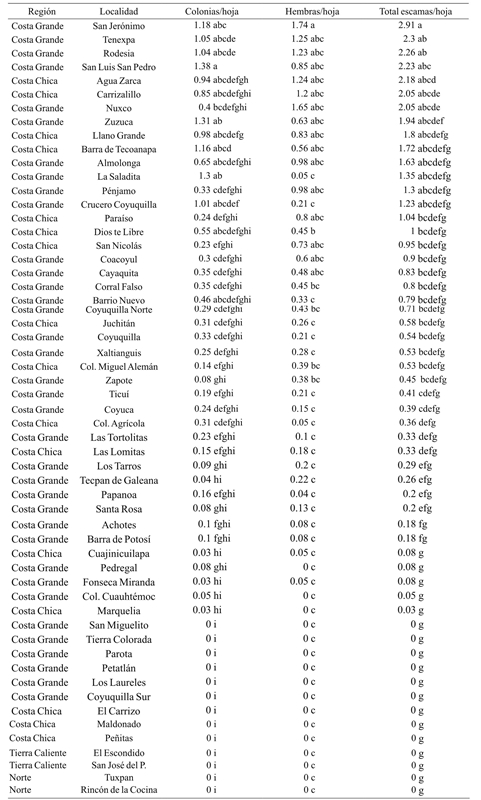

Distribution by municipality. In the Table 3 shows the distribution of EBM at the municipal level, where the highest incidence was in Benito Juárez, with 2.91 total scales/leaf, with significant differences with the remaining 17 municipalities (p≤ 0.05); in Juchitan, Marquelia and Tecpan of Galeana there were values of 1.25 and 1.23, which showed significant differences (p≤ 0.05) with 7 municipalities. Eight municipalities had incidences of 1.09 to 0.42 total scales/leaf that did not have significant differences with the municipalities where EBM was not detected.

Table 3 Geographic distribution of mango white scale in leaves and fruits by municipality in Guerrero, 2012-2014.

Las medias en cada columna con letras distintas son significativamente diferentes (Tukey, p≤ 0.05).

The regions where EBM was not located were Tierra Caliente, Norte and Centro. In the other regions of Costa Grande and Costa Chica, nine localities without EBM were located; however, in contiguous localities if there was a high incidence.

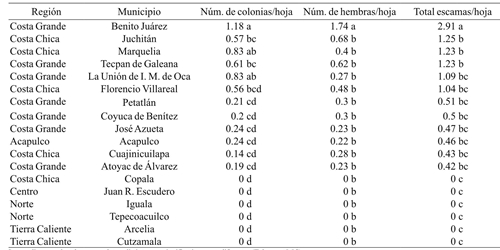

Distribution to cultivate. In Table 4, the incidence of EBM by cultivar is shown, where Manila showed higher values, with 1.99 total scales/leaf, with significant differences (p≤ 0.05) with the other cultivars. Tommy Atkins, Ataulfo, Haden and Kent had values of 0.78, 0.75, 0.62 and 0.01, with significant differences (p≤ 0.05) with the creole who showed absence of EBM.

Table 4 White-scale foliage populations to be cultivated in Guerrero.

Las medias en cada columna con letras distintas son significativamente diferentes (Tukey, p≤ 0.05)

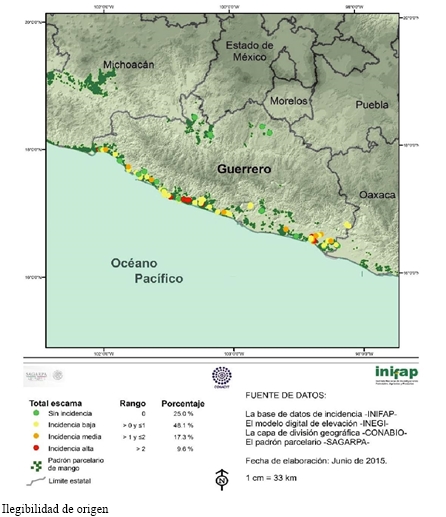

Geographical distribution. The spatial distribution of average incidence per leaf of colonies and totals (females + colonies) in Guerrero is presented in Figure 1 and 2. This cartography allows to visualize in a clear and practical way, the geographical context in which the scale is circumscribed in the state; it also allows us to analyze the magnitude of the incident as a whole.

Figure 2 Geographic distribution of the incidence of total EBM (females + colonies) in mango, Guerrero.

However, if the maps are scaled at the state level, it can be seen that the incidence of colonies requires attention in the municipalities of Tecpan of Galeana, Benito Juárez and Marquelia. In as much the risk by high incidence (total of females and colonies) is priority in the Union of Isidoro Montes de Oca, Tecpan de Galeana, Benito Juarez, Juchitan, and Marquelia.

Figure 3 shows the distribution of females, which contrasts with the other two maps, because the presence of EBM in the state, is associated mainly with females, which is a focus of attention, because these can shoot the current classification of colonies “without incidence” in the other municipalities.

In this work it was detected that the region of the Costa Grande, Acapulco and Costa Chica is where the EBM is presented. It is absent for the moment in Tierra Caliente, Norte and Centro of Estado. Although, in some coastal municipalities, such as Copala, the EBM is absent, it is likely that it is due to the little movement and mango area in this municipality and the natural barriers that are found in the localities.

Regarding the cultivars, it is observed that the most affected are Manila, later Tommy Atking, Ataulfo and Haden, probably because they are the cultivars most widely distributed in the Coastal Region of the state. Finally, in creole where the EBM was not located since this material was sampled in the production areas where there is still no damage by EBM. In the geographical distribution maps, another factor of analysis is the environment, since it is observed that the scale is related to temperature and relative humidity, which are the factors that give features in common to the areas of greater presence of total scale in Guerrero , which coincides with that reported by Miranda-Salcedo and Urías-López (2013), as well as Noriega-Cantú et al. (2013), in that the warmer climates with higher environmental humidity in the area favor the presence of EBM.

Under field conditions it was found that temperature and wind positively correlate with abundance of A. tubercularis, while precipitation and relative humidity correlate negatively (Noriega-Cantú et al., 2016). The high incidence of EBM occurs when average temperatures increase and precipitation decreases, which is why A. tubercularis is a pest dependent on temperature and dry conditions (Urías-López et al., 2010). However, it is possible that due to the conditions of high temperatures and extreme relative humidities that occur during several months of the year in some municipalities of the Tierra Caliente and Norte regions the white scale does not thrive.

Conclusions

A. tubercularis is found in the Costa Grande Region, Acapulco and Costa Chica, which make up the area with the highest mango production in the state of Guerrero.

No presence of the white scale was detected in the Hot and North Earth Regions.

The highest incidence of white scale at the municipal level was San Jeronimo, followed by Juchitan, Marquelia and Tecpan de Galeana.

The cultivars in which the largest scale presence was found were Manila, Tommy Atkins, Ataulfo and Haden, followed by Kent. In creole mango, the presence of the scale was not detected.

Literatura citada

García, E. 2004. Modificaciones al Sistema de Clasificación de Köppen. Serie Libros No. 6. Quinta Edición: corregida y aumentada. UNAM. México, D. F. 98 p. [ Links ]

García-Álvarez, N. C.; Urías-López M. A.; Hernández-Fuentes, L. M.; González-Carrillo, J. A.; Pérez-Barraza M. H. y Osuna-García, J. A. 2014. Distribución de la escama blanca del mango Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead (Hemiptera: Diaspididae) en Nayarit, México. Acta Zool. Mex. (ns)30:321-336. [ Links ]

Hodges, A. C. Hodges, G. S. and Wisler, G. C. 2005. Exotic scale insects (Hemiptera:Coccoidea) and whiteflies (Hemiptera: Aleyrodidae) in Florida’s tropical fruits: an example of the vital role of early detection in pest prevention and management. P. Fl. St. Hortic. Soc. 118:215-217. [ Links ]

INEGI. 2007. (Instituto de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). Datos vectoriales de la base referencial mundial de recurso suelo (WRB-2006). [ Links ]

INEGI. 2016. (Instituto de Estadística, Geografía e Informática). Conociendo Guerrero. Sexta edición. 36 p. [ Links ]

Isiordia-Aquino, N.; García-Martínez, O.; Flores-Canales, R. J.; Díaz-Heredia, M.; Carvajal-Cazola, C. R y Espino-Álvarez, R. 2011. El cultivo de mango en Nayarit, acciones e impacto en materia fitosanitaria 1993-2010. Rev. Fuente. 2:34-43. [ Links ]

Juárez-Hernández, P. 2014. Respuesta fotosintética del mango en función del daño por escama blanca del mango (Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead). Tesis de Doctorado en Ciencias, Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo, Texcoco, Estado de México, México. [ Links ]

Miranda-Salcedo M. A. y Urías-López, M. A. 2013. Distribución geográfica de la escama blanca del mango Aulacaspis tubercularis en Michoacán. Entomol. Mex. 12(2):1000-1003. [ Links ]

Moharum, F. A. 2012. Description of the first and second female and male instars of white mango scale Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead (Coccoidea:Diaspididae). JOBAZ. 65:29-36. [ Links ]

Noriega-Cantú, D. H.; Urías-López, M. A.; González-Carrillo, J. A. y López-Guillén, G. 2016. Abundancia temporal de la escama blanca del mango, Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead, en Guerrero, México. Southwestern Entomologist. 41(3):845-854. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3958/059.041.0326. [ Links ]

Noriega-Cantú D. H.; Urías-López, M. A.; López-Estrada, M. E.; Cruzaley-Sarabia, R. C. y Ulises-Martínez, A. 2013. Fluctuación poblacional y distribución de la escama blanca, del mango (Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead) en la Costa de Guerrero, México. VIII Congreso Latinoamericano de Entomología. In: XLVIII Congreso Nacional de la SME. 23 al 27 de junio de 2013. Ixtapa Zihuatanejo, Guerrero, mango. 1066-1071. [ Links ]

Peña, J. E. and Mohyuddin, A. I. 1997. Insect pest, In: Litz, R. E. (Ed.). The mango: botany, production and uses. CAB International, Wallingford, UK. 327-362 pp. [ Links ]

SAGARPA. 2016. Secretaría de Agricultura, Ganadería, Desarrollo Rural y Pesca. Sistemas de Información Agropecuaria y Pesquera (SIAP). Estadísticas de la producción agrícola en México. México, D. F. Internet. http://www.sagarpa.gob.mx. [ Links ]

SAS Institute, Inc. 2010. SAS user’s guide: Statistics. Release 9.3. Ed. SAS Institute Incorporation. Cary, C, SA. 1028 p. [ Links ]

Urías, L. M. A. y Flores, R. C. 2005. La escama blanca, Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead (Homoptera:Diaspididae) una nueva plaga del mango: fluctuación poblacional y anotaciones biológicas. Entomol. Mex. 4:579-584. [ Links ]

Urías, L. M. A. y Flores, R. C. 2005. La escama blanca, Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead (Homoptera:Diaspididae), una nueva plaga del mango: fluctuación poblacional y anotaciones biológicas. Entomol. Mex. 4:579-584. [ Links ]

Urías, L. M. A. 2006. Principales plagas del mango en Nayarit. In: el cultivo del mango: principios y tecnología de producción. Vázquez, V. V. y Pérez, B. M. H. (Eds.). IINIFAP. Centro Regional de Investigación Pacífico Centro. Campo Experimental Santiago Ixcuintla. 211- 234 pp. [ Links ]

Urías, L. M. A.; Osuna-García, J. A.; Vázquez-Valdivia, V. y Pérez-Barraza, M. H. 2010. Fluctuación poblacional y distribución de la escama blanca del mango (Aulacaspis tubercularis Newstead) en Nayarit. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Hortic. 16 (2):77-82. [ Links ]

Received: October 2017; Accepted: November 2017

texto en

texto en