Services on Demand

Journal

Article

Indicators

-

Cited by SciELO

Cited by SciELO -

Access statistics

Access statistics

Related links

-

Similars in

SciELO

Similars in

SciELO

Share

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

Print version ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 n.7 Texcoco Sep./Nov. 2017

Articles

Experiences of INIFAP hybrid corn seed producers in the Tlaxcala market

1Campo Experimental Valle de México-INIFAP. Carretera Los Reyes-Texcoco km 13.5. Coatlinchán, Texcoco, Estado de México.

2Campo Experimental Mocochá-INIFAP. Carretera Mococha-ex hacienda Carolina km 1.5.

3Campo Experimental Cotaxtla-INIFAP. Carretera Federal Veracruz-Córdoba km 34.5. Medellín de Bravo, Veracruz.

4Sitio Experimental Tlaxcala-INIFAP. Carretera Tlaxcala-Santa Ana km 2.5. Col. Industrial, Tlaxcala, Tlaxcala.

This article to analyzes the difficulties faced by producers of hybrid maize seeds and varieties of CEVAMEX-INIFAP in the state of Tlaxcala, after 12 years of being adopter of this technology generated by the CEVAMEX. It is a sociological, exploratory and descriptive study where the experiences of the adoptive producers were the fundamental element. It an individual cases producers, companies and firms were considered, all producers improved maize seed. The objectives of this work they were: identify the level of adoption according to an indicator developed on purpose for this investigation. Describe the experiences of producers in the production and sale of seeds and identify the variables that drive or hinder the adoption process. Thematic interviews were conducted, focal type meetings and questionnaires were applied. The topics discussed were availability of basic and registered seed, agronomic management and sales market to get certified seed producers. The information collected was compared between the various techniques used in the field of information. The results suggest that the experiences of producers are framed by oligopolistic conditions the corn seed market is imposing in recent years, on situation that influences their decision to continue or discontinue the adoption process.

Keywords: adoption of maize seeds; hybrid maize seeds; maize seed producers

Este artículo analiza las dificultades que han enfrentado los productores de semillas de maíz híbrido y variedades del CEVAMEX-INIFAP en el estado de Tlaxcala, después de 12 años de ser adoptantes de esta tecnología generada por el CEVAMEX. Es un estudio sociológico, exploratorio y descriptivo donde las experiencias de los productores adoptantes fue el elemento fundamental. Se consideraron casos individuales de productores, de sociedades y empresas, todos ellos productores de semillas de maíz mejorado. Los objetivos de este trabajo fueron: identificar el nivel de adopción de acuerdo con un indicador desarrollado exprofeso para esta investigación. Describir las experiencias de los productores en la producción y venta de semillas e identificar las variables que impulsan o limitan el proceso de adopción. Se realizaron entrevistas temáticas, reuniones de tipo focal y se aplicaron cuestionarios. Los temas abordados fueron disponibilidad de semillas básica y registrada, manejo agronómico y mercado de ventas de la semilla certificada que obtienen los productores. La información recabada se contrastó entre las diferentes técnicas de información usadas en campo. Los resultados apuntan que las experiencias de los productores se encuentran enmarcadas por las condiciones que el mercado oligopólico de semillas de maíz está imponiendo en los últimos años, situación que influye en su decisión de continuar o interrumpir el proceso de adopción

Palabras clave: adopción de semillas de maíz; productores de semillas de maíz; semillas de maíz híbrido

Introduction

Since the demise of the National Seed Producer (PRONASE), Campo Experimental Valle de Mexico (CEVAMEX) of the National Institute of Livestock Agricultural and Forestry Research (INIFAP), has spent several years transferring its corn seeds. In this process has been involved with two links of this chain. The first, seed producers who have trained and trained to turn this s sell certified seed producers of grain and corn stover, who make up the second link. This work training and transfer, has been developed in different states of Mexican republic, including Tlaxcala. The result s annual sales are parent seed constants has done CEVAMEX do the producers of this state from 2004 to 2015. What is considered a success, since the commercial use of the improved maize is the best indicator of its adoption.

This research or to orient know dich process of adoption and the current situation of the adoptive producers in the seed market. He began by considering that the market that producers access to sell their products, plays a fundamental role to motivate or discourage them in the adoption process. Above all, in the case of the improved maize seed market, since it is an oligopolistic market. Oligopoly is a form of organization characterized by the existence of a small number of companies, where every produce a homogeneous good (Gould et al., 1994).

Each company is large enough in relation to the market, so that their actions significantly influence their rivals (Henderson et al., 1991). For this reason and in the pursuit of greater profit, companies seek to build coalitions whose purpose is to limit the scope of competitive forces within the same market. For example, they may agree the product price and production volume leading to market. When the coalition is given, competition is established by advertising, product quality, packaging design (Gould et al., 1994). Varian (1999) considers that there is no general model that describes the behavior of all oligopolies; however, if there are possible models like the positioning of leading companies in setting prices or production volumes or, agreements between them.

Another characteristic that speaks of the oligopolistic companies is that they establish barriers to avoid the entry of new companies or, they initiate a strong fight between those already established. For example, because they handle homogeneous products, a company can create several brands, so that companies that are considering entering, face serious difficulties to do something different. As already mentioned, the management of price and volume of production within margins that allow them to generate profits is an impediment to entry, or a struggle between those already established (Nicholson, 1997).

Roth and Clementi (2010) work on the psychological profile of potential adopters. They consider that adoption is behavior that is intimately linked to change. The psychological variables that influence the willingness to change are cognitive, affective, attitudinal and behavioral. These variables along with the technological ones (their comparative advantages, their usefulness, their complexity, etc), the social, demographic variables (the adopters’ age and sex, their educational level, etc) and the variables of the environment or context the political and legal-regulatory framework, market conditions, technology costs, etc) help to understand the decision to adopt or not. (Lerner, 1964; Foster, 1967; Hagen, 1970; Cáceres et al., 1997) consider small producers as conservative and with little predisposition to change. Other views, however, consider that the producer is always an innovator (Cáceres et al., 1997).

Adoption is also understood as the decision of producers to use a particular technology, depending on the price of the product or innovation, the availability of the product on the market, the difficulty of adopting innovation (Sagastume et al., 2006). Other authors comment that adoption is a process that starts from knowledge, interest, evaluation and testing of a product or innovation (Galindo, 2004). This means that the adopter is going through different moments to reach the decision to adopt or not. In this sense, Roth and Clementi (2010) affirm that adoption is a process that is expressed in an s-shaped sine curve, which allows the adoption rate to be identified according to each adopter’s adoption rate CIMMYT (1994). Considering this framework, the question that gave rise to this study was: what aspects influence a seed producer obtained by CEVAMEX-INIFAP to decide to continue or withdraw from the adoption process?

The objectives of this work were: a) to identify the level of adoption in the production of improved maize seeds, according to an indicator developed on purpose for this research; b) describe the experiences they have had in the production and sale of seeds, the producers of Tlaxcala who sell improved maize seed of CEVAMEX ; and c) identify the variables that drive or limit them in the adoption process.

Materials and methods

The subject of study of this research was the adoption of improved maize seeds of CEVAMEX-INIFAP. The subject of study was the seed producer of the state of Tlaxcala. This research was defined as sociological, exploratory and descriptive in which, through the historical reconstruction of facts and the experiences of the study subjects, it was possible to construct the adoption process, identifying problems and achievements that have had the producers in the field of production and sale of maize seed. The research began with a bibliographical review on the maize seed market in Mexico and in particular in the state of Tlaxcala. Subsequently fieldwork was carried out where three techniques were used to collect direct information: thematic interviews, questionnaires and focal type meetings.

Thematic interviews were conducted with the producers, based on the Altamirano (2006) methodological proposal. The objective was to know how the adoption process happened individually. A questionnaire was applied with open qualitative and quantitative questions closed, referring to the volume of purchases and seeds that demand, years that have been buying these seeds and problems that they face in the supply and in the production. The focus group meetings discussed the problems faced by producers in buying parental seeds, producing certified seeds and selling them. The central aspect of these types of meetings is to provoke discussion based on the personal experiences of those present and is guided through semi-structured questions (Escobar, 2011).

In addition to the above, the records of sales of progenitor seeds of CEVAMEX-INIFAP were followed up. The number of people surveyed was defined by voluntary nonprobabilistic sampling. In the voluntary sampling as its own name says, the people who make it up are those who agree to participate voluntarily in the invitation to participate in the surveys. The sample size is defined by the investigator (a) under non-probabilistic or random criteria (Shao, 1988). The selection of the producers who were invited to the group meetings as well as the ones that were interviewed was intentional. Selection is usually done by the attributes of these individuals (Shao, 1988).

The 18 questionnaires were applied: six to individual producers and 12 to producers representing rural production enterprises. Two focus group meetings were held, ensuring that there was uniformity in the conditions of the producers. One was in the town Carrillo Puerto of the Altzayanca municipality, which was attended by six individual producers, the other in the offices of the INIFAP Tlaxcala Experimental Site, which was attended by eight producers, all representatives of rural production companies. Four interviews were conducted with key informants. Three to producers, the first in the locality Francisco Villa municipality of Sanctorum Lázaro Cárdenas.

The producer is the son of the founder (already deceased) of the company Sociedad Rivera López SPR. LMI, the second in the locality Espírito Santo of the municipality of Ixtlacuixtla, with the founder of the company ESNAVIG SPR. LMI and the third with the founder of the company San Antonio Atotonilco. The fourth interview was made to the researcher of the Tlaxcala Site of INIFAP, who has been a key player in the training of maize seed producers in the state of Tlaxcala. In all, considering the three techniques, information was obtained from 35 producers, which appear in the sales records of CEVAMEX, plus that of the researcher (FAO, 2009).

To measure the years of adoption of CEVAMEX’s improved maize seeds, an indicator of the level of adoption of the seed technology component was used, which was designed for this research. Consider five years and take values from 1 to 0.2, depending on the number of years that the study subject has planted improved maize seed of CEVAMEX-INIFAP. Part of considering that the producer when he knows the product and tries it a year, starts the process. The value is 0.2. If it continues, during the next three years the producer will familiarize himself with the agronomic management of the seeds, with the crosses, with the process of profit and packing, with the market that supplies him with progenitor seeds and the sales of certified seed.

The farmers who sow it during the next three years and find advantages in all these aspects are more likely to reach the fifth year and consider themselves an established adopter; its value will then be one, the values above indicate that it is in process. Considering what Galindo (2004) says, the constant use of the seeds for five years allows the producer to know and evaluate the innovation, adding that in the same period he can know the market response to his product. This indicator qualifies adoption in: adoptive producers, producers who are in the process of adoption and producers who abandon adoption.

Results and discussion

History of the adoption of improved maize INIFAP in the state of Tlaxcala seeds

During the years of operation of the National Seed Producer (PRONASE), the improved maize seeds marketed in the state were mainly from CEVAMEX-INIFAP. PRONASE, through INIFAP researchers, trained producers in the state of Tlaxcala to reproduce seeds H-30, H-33 and H-34 (interview with INIFAP maize seed producer). The training was received from the Tlaxcala Experimental Site of INIFAP (Barillas, 2010).

Seeds of transnational and national private companies were also marketed. With the closing of PRONASE, 2004. The Tlaxcala market opens and begins a restructuring of the same, where the participation of transnational companies is increasing. At the beginning, Asgrow is presented with the seeds Halcón, Gavilán, Condor and Buho, Hart Seed with Z-60 and Mexican companies like Pastege today Aspros with AS-721, AS-820, AS-600 and seeds of INIFAP H-28, H-30, H-33, H-34, VS-22, V-23, and Texcoco seeds with PROMESA (AMSDA, SF and INIFAP researcher information).

In that same year (2004) SAGARPA, SNICS, INIFAP and the Produce Foundation Tlaxcala, initiated a program that they called “Certified Seed Production for the state of Tlaxcala”. INIFAP was responsible for the transfer and training. Seeds H-40 and H-48 (the H-30, H-33 and H-34 came out of the market) were introduced to the market. The goal was to train INIFAP seed producers to produce and market them later (Barillas, 2011).

For approximately the first six years, producers sold their production annually to the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, Rural Development, Fisheries and Food (SAGARPA) and SAGARPA in turn sold it at subsidized prices to corn farmers through the strategic project of support to the corn and bean production chain (PROMAF). The seed producers delivered to SAGARPA from 12 to 14 thousand sacks annually (information obtained from focal meeting). Each sack covers one hectare of sowing, which resulted in the planting of an average annual crop of 13 000 hectares with improved maize seed by INIFAP (information obtained from a focal type meeting).

Characteristics of INIFAP improved maize seed producers

The seed producers to whom the questionnaire was applied belong to the municipalities of San Damián Texoloc, Sanctorum de Lázaro Cárdenas, Muñoz de Domingo Arenas, Xicohtzingo, San Jerónimo Zacualpan, Ixtlacuixtla of Mariano Matamoros, Nativitas, Benito Juárez, Tlaxco, Huamantla, Santa Cruz Quilehtla and Huamantla. On average, they are 6.3 years old, being INIFAP’s maize seed producers. The 83% of the producers work with irrigated land.

With the exception of one producer, all the others were formed by INIFAP. Sixty percent of them formed organizations or companies and 40% worked individually. All producers of the show said that in addition to producing corn seeds, they plant corn for grain. In addition to maize, 27% also grow beans, barley, oats and wheat, the last three crops for sale on the market. Other activities other than agriculture were livestock and commerce that make up their main source of income, in which they work individually.

Experience INIFAP seed producers in producing and selling seeds in the market Tlaxcala

The producers subject to this study had to face different problems during the adoption process, some related to the supply of parent seeds, others with production and others in the sales market. Concerning the supply of seeds, 100% of the sample producers said CEVAMEX at the beginning of the period covered their demand for basic and registered seeds, but as more producers joined this activity, individual seed demand has been completely covered again.

There were those who said that because of lack of parent seed, they cannot cover their demand for certified seed, so they have lost customers. Regarding the production process, 22% of the producers mentioned a problem, they referred to the difficulty of having isolated lots to obtain seed certified by SNICS.

Regarding the problems of the sales market, 100% of the sample producers mentioned competition with transnational companies as the main one. They mentioned aspects of this competition: the hybrid seeds of the transnational companies have more prestige, so the producers prefer them, they also bring new seeds to the market faster, they have a better presentation, they work with lower costs to produce and pack, our seeds are sold very slowly because the market of Tlaxcala is very small and there is great variety of hybrid seeds of transnational companies.

According to field information, producers who remained on the market with certified seed had to do a lot of work to regain consumer confidence. The market was displacing declared seed producers, even leaving them out. The problem of demarcation occurred in the municipality of Altzayanca (which is one of the municipalities with the largest area planted with maize for grain and forage in the state), and was also mentioned by 11% of the producers belonging to the municipalities of Sanctorum and Huamantla, who, unlike the previous ones, did solve the problem. Córdova (2011), who carried out a work in Tlaxcala with five organizations of maize seed producers improved by INIFAP, comments that 21% of their sample mentioned that the delimitation of the land was the main problem they faced in the year 2010.

These organizations are in the municipalities of Sanctorum of Lázaro Cárdenas, Ixtacuixtla of Mariano Matamoros, Chiautempan, Lázaro Cárdenas and San Jerónimo Zacualpan. This allows you to see that to analyze the adoption process should also consider economic and agronomic reasoning, social and cultural context in which it develops proc said adoption (Cáceres, 1997).

Producers who formed organizations and companies, had the financial capacity to rent land and solve this problem of demarcation, were able to obtain quality seed certified by the SNICS. Córdova (2011) assures that 68% of the producers of his sample, worked with leased land. According to information from the CEVAMEX sales records, the average area sown by individual producers is smaller compared to the area sown by those who were organized in companies. Individual producers that represent 42%, plant areas ranging from one to six hectares, with an average of 2.2 hours, average 1.6 and one fashion. The 58% formed by companies and organizations, run a range that runs from one to nineteen, the average being 4.7 hours, the median of four and the fashion of four.

The number of hectares planted with the number of hectares planted and the four farmers with the most years of seed reproduction were found to plant more hectares (Table 1).

1=Información de productores que se obtuvo a través de los registros de ventas de CEVAMEX. Fuente: elaboración con base en información de los cuestionarios y registros de ventas de semilla progenitora del CEVAMEX.

Table 1 Number of producers according to years of reproduction of maize seed and hectares sown per year (2005 to 2015 period)

Sale of progenitor seed in the CEVAMEX-INIFAP

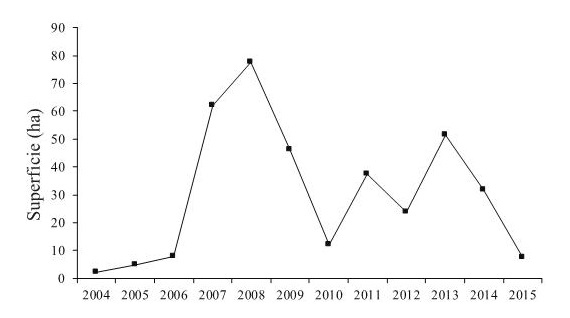

An indicator of adoption is the positioning of seeds in the sales market. From 2004 to 2015, CEVAMEX has sold improved maize seed by CEVAMEX to producers in the state of Tlaxcala. With the sale of basic and registered seeds, year after year, different amounts of hectares have been planted, reaching an area of approximately 77.5 ha in 2008 (Figure 1).

In the Figure 1 describes the behavior of the surface planted in the state of Tlaxcala for 11 years, with progenitor seed purchased at CEVAMEX. In this graph we can see what CIMMYT (1994) reported when he says that adoption starts slowly, followed by a faster increase and then a slowdown. Although it may be normal behavior, this reduction represents a worrying situation.

The INIFAP has faced difficulties in supplying the quantity demanded for basic and registered seeds, as the producers say, and this may explain in part the fall of the area sown. This does not denote a drop in the demand for seed or certified seed. Public institutions, unlike private companies, work non-profit, do not seek to increase their utility, but “offer a public service”. They work with budgetary constraints and their profits are positive but decreasing (Nicholson, 1997) which is probably reflected in the limitation of progenitor seed production.

Current situation

The producers who are still in force said they are facing problems with the marketing of their seeds. In the year 2013, PROMAF changes to an incentive program for maize and bean producers (PIMAF). Currently, with the PIMAF (where it continues to support corn grain producers through selling at subsidized prices, packages that include seeds, fertilizers, herbicides and biofeedants), the Federal Government withdraws from participating in the commercialization of the seed and leaves it to private companies certified by SAGARPA (SAGARPA, 2014).

These companies are made up of producers with a mainly marketing orientation, who have storage warehouses, truck fleet, scales and sell agrochemical products in different states of the Mexican Republic. Some of these companies are authorized by the transnationals to sell their seeds and their agrochemicals. In particular, for the producers under study, it meant the end of the marketing support offered by the Federal Government. Parallel to this is the State Government’s Agricultural Production Support Program (SEFOA, 2015).

The transnational companies have several years of experience in the competition of the markets, their participation displaces to medium and small entrepreneurs. The competition is even greater, as they continue to consolidate and strengthen, is the case of Monsanto that bought the companies Asgrow, Cargill International Seed, Hartz Seed, among others, in addition to participating with Dekalb and forms alliances with Pioneer (Córdoba, 2000) who acquired Dupont and Phi de México SA de CV.

The seed producers of CEVAMEX-INIFAP, have to negotiate with the private companies that participate with the Federal Government with the sale of packages, so that through them they sell their seeds. At the moment they have not been successful by this means, since the entrepreneurs prefer to distribute the seeds of transnational corporations (direct information obtained from group meeting). As for the tianguis, have made attempts to enter but have failed.

The request to: have a first level organization, a rural production company (SPR), a large volume of seeds, which is why the second level organization in which several SPRs are organized in rural production enterprises (RPE) (Estudios Agrarios, SA) to commercialize its production. Once trained as EPR, they must register with Social Security, at least four workers. The producers pointed out that they have met these conditions without exception, except for the last requirement. They noted that insuring four people means a sharp increase in their production costs. Information obtained at a focal type meeting. According to Nicholson (1997), this requirement can be interpreted as a legal barrier to entry to the market, typical of oligopoly competition, are actions undertaken by governments arguing the management of markets.

In the focus group meetings, the producers commented that the corn seed market’s rearrangement is due to the greater bargaining power that transnational corporations have with the Federal and State governments. They consider it a political and reorganization issue that is leaving them out. They consider that this is the main problem and not the quality of the seeds they sell. In fact, CEVAMEX-INIFAP seeds are still in demand despite the difficulties described above, mainly to assist the producers in the eastern region of the state of Tlaxcala, where sandy soils are used under temporary conditions (interviews with producers of seed and authorized seed seller of transnational corporations).

This region is served mainly by two companies of the State of Mexico, one of them El Trebol, and a producer of the state of Morelos. These companies that participate in the seed trade, offer seeds of CEVAMEX-INIFAP. The small producers of the state of Tlaxcala are maintained because they take their production to other states, such as Puebla in the market of San Martín Texmelucan, and because they have kept customers captive for years.

The INIFAP improved maize seed adoption process

The records of sales of maize seed of CEVAMEX-INIFAP during the period 2005 to 2015 were reviewed. It was verified that seeds have been sold year after year during this period, to producers of Tlaxcala. In total there were 43 buyers representing individual organizations, companies and producers. In this period, some started individually and later formed organizations or companies. With the intention of not duplicating the count of these cases, they were followed up and in total 36 buyers who are currently at different times of the adoption process Table 2).

*=Un productor comentó que interrumpió por un año la compra de semilla al CEVAMEX, argumentando que la semilla certificada que había producido en 2014, la vendió de manera muy lenta por lo que en 2015, aun contaba con semilla certificada. Fuente: elaborado con base a los registros del CEVAMEX e información obtenida en el trabajo de campo.

Table 2 Value of the adoption indicator applied to the producers of certified maize seed of CEVAMEXINIFAP of the state of Tlaxcala during the period 2005-2015

In the first years of the study period the volume of seed sold by CEVAMEX reached its highest level, which coincides with the support received by producers from SAGARPA. By 2010, when the MasAgro Program emerges, both the number of producers and the volume of sales fall. It recovers from 2011 until 2013, to fall again in 2014. This fall coincides with the closing of PROMAF. In this second stage, the volume of seed sold is reversed, it is below the number of producers (Figure 2).

Conclusions

Tlaxcala state seed producers who were trained by INIFAP, adopted the technology successfully in most cases, as they succeeded in producing certified hybrid corn seed. To achieve this, producers are defined as innovators in production, packaging and organization. Their learning has allowed them to stay in the market for at least 15 years. During this time, they have faced two important and definitive moments in their adoption process: to open the market as producers of hybrid seeds in the different localities of the municipalities of Tlaxcala and to keep up with the changes that the market has had since the disappearance of the PROMAF and the emergence of seed seedling.

Producers appreciate that in this new context, INIFAP seeds can compete in quality and price. The main problem is established, in the few possibilities of negotiation that the small seed companies of Tlaxcala have, in the context of the new organization of the market of seeds of this federative entity. Producers describe well the difficulties of participating in an oligopolistic market. Markets made up of chains and networks of value, strongly integrated, although there are conflicting economic interests between the participants of the different links, moreover, if the primary producers continue to produce and market by traditional means.

According to the experience of the Tlaxcala seed producers, the question arises that the problem of the deficit of improved seed production in the center and southeast of the country can be solved by training farmers to form the seed companies proposed MasAgro since it has not been said, how these new producers will be integrated into that market.

Literatura citada

Altamirano, G. 2006. Metodología y práctica de la entrevista. En la historia con micrófono. Instituto Mora. 2º (Ed). México, D. F. 63-78 pp. [ Links ]

AMSDA. S. F. Diagnóstico sistema producto maíz del estado de Tlaxcala. http://www.amsda.com.mx/prestatales/estatales/tlaxcala/premaiz.pdf [ Links ]

Barillas, S. M. 2010. Producción de semilla certificada en el estado de Tlaxcala. Caso 1. 44 p. http://www.siac.org.mx/fichas/36%20tlaxcala%20maiz.pdf [ Links ]

Brambila, P. J. de J. 2011. Bioeconomía. Conceptos y fundamentos. SAGARPA-COLPOS. 334 p. [ Links ]

Branthomme, A.; Altrell, D.; Kamelarczyk, K.; Saket, M. 2009. Monitoreo y evaluación de los recursos forestales nacionales. Manual para la recolección integrada de datos de campo. Versión 2.2. FAO. Roma. 216 p. (Documento de trabajo NFMA 37/S). [ Links ]

Cáceres, D.; Silvetti, F.; Soto, G. y Rebolledo, W. 1997. La adopción tecnológica en sistemas agropecuarios de pequeños productores. Agro sur. 25(2):123-135. http://mingaonline.uach.cl/scielo.php?script=sci-arttext&pid=S0304-88021997000200001&lng=es&nrm=iso> [ Links ]

CIMMYT (Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maíz y Trigo) 1993. Programa de economía. La adopción de tecnologías agrícolas: guía para el diseño de encuestas. Singapur https://books.google.com.mx/books? [ Links ]

Córdova, de O. R. 2000. Políticas gubernamentales para fortalecer la industria de semillas, generación y transferencia de tecnología en semillas. Políticas y programas de semillas en América Latina y el Caribe. https://books.google.com.mx/books?131-158 pp. [ Links ]

Córdova, I. E. 2013. Análisis socioeconómico de la producción de semilla certificada de maíz, en el estado de Tlaxcala. Tesis de Maestría. Colegio de Postgraduados. 85p. http://www.biblio.colpos.mx:8080/xmlui/bitstream/10521/1960/2/cordova-islas-e-mcdesarrollo-ruiral-2013.pdf. [ Links ]

Donnet, L.; López, D.; Arista, J.; Carrión, F.; Hernández, V.; González, A. 2012. El potencial de mercado de semillas mejoradas de maíz en México. Documento de trabajo núm. 8. CIMMYT. México. 22p. [ Links ]

Escobar, J. y Bonilla, J. I. 2011. Grupos focales: una guía conceptual y metodológica. Cuadernos Hispanoamericanos de Psicología. 9(1) 51-67. [ Links ]

FAO. 2009. Manual para la recolección integrada de datos de campo. Documento de trabajo. NFMA 37/S- Roma. 216p. http://www.fao.org/3/a-ap152s.pdf [ Links ]

Galindo, G. G. 2004. Estrategias de difusión de innovaciones agrícolas en México. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Zonas Áridas. 3ra edición. [ Links ]

García, S. J. A. y Ramírez, J. R.2014. El mercado de la semilla mejorada de maíz (Zea mays L.) en México. Un análisis del saldo comercial por entidad federativa. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 37(1):69-77. [ Links ]

Gould, J. P. y Lazear, E. P. 1994. Teoría microeconómica. FCE. 3rª edición, México. 870 p. [ Links ]

Henderson, J. M. y Quandt, R. E. 1991. Teoría microeconómica. 3rª edición. 1rª reimpresión. Ariel Economía. España. 534 p. [ Links ]

Luna, M. B.; Hinojosa, R. M. A.; Ayala, G. O. J.; Castillo, G. F. y Mejía, C. J. A. 2012. Perspectivas de desarrollo de la industria semillera de maíz en México. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 35(1):1-7. [ Links ]

Nicholson, W. 1997. Teoría microeconómica. Principios básicos y aplicaciones. Mcgraw-Hill. España. 599 p. [ Links ]

OCDE y EUROSTAT. 2006. Manual de Oslo. Guía para la recogida e interpretación de datos para la interpretación de datos para innovación. Tercera edición. España. 192 pp. http://www.uis.unesco.org/library/documents/oecdoslomanual05-spa.pdf [ Links ]

Roth, E. y Clementi, C. 2010. Innovación tecnológica: características psicológicas del adoptante temprano. Revista Ciencia y Cultura. 11(24). [ Links ]

SAGARPA (Secretaría de Agrícultura, Ganadería,Desarrollo Rural, Pesca y Alimentación). 2014. Descripción de PIMAF. http://www.sagarpa.gob.mx/ProgramasSAGARPA/2014/fomento_agricultura/PIMAF/Paginas/Descripci%C3%B3n.aspx. [ Links ]

Sagastume, N.; Rodríguez, R.; Obando, M.; Sosa, H. y Fishler, M. 2006. Guía para la elaboración de estudios de adopción de tecnologías de manejo sostenible de suelos y agua. Programa para la Agricultura Sostenible en Laderas de América Central, Manejo de Recursos Naturales Economía Rural Gobernalidad Local y Sociedad Civil y Agencia Suiza para el Desarrollo y Cooperación. Tegucigalpa, Honduras29 p. [ Links ]

SEFOA (Secretaría de Fomento Agropecuario). 2015. Periódico Oficial núm. 1. Cuarta sección, Enero 7. 2 p. [ Links ]

Shao, S. 1988. Estadísticas para economistas y administradores de empresas. Edición 1988. Herrara Hermanos. 786p. [ Links ]

SIAP. 2015. Producción agrícola. http://www.siap.gob.mx/cierre-de-laproduccion-agricola-por-estado/ [ Links ]

SIAP. 2015. Cierre de la producción agrícola por estado. http://www.siap.gob.mx/cierre-de-la-produccion-agricola-por-estado. [ Links ]

Varian, H. R. 1999. Un enfoque actual. Microeconomía Intermedia. 5tª edición. Antoni Bosch. España. 726 p. [ Links ]

Received: September 01, 2017; Accepted: November 01, 2017

text in

text in