Serviços Personalizados

Journal

Artigo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Acessos

Acessos

Links relacionados

-

Similares em

SciELO

Similares em

SciELO

Compartilhar

Revista mexicana de ciencias agrícolas

versão impressa ISSN 2007-0934

Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc vol.8 no.6 Texcoco Ago./Set. 2017

Articles

Economic and financial viability of cactus pear (Opuntia ficus-indica)crop in Nopaltepec, Estate of Mexico

1Universidad Autónoma Chapingo-Centro de Investigaciones Económicas, Sociales y Tecnológicas de la Agricultura y Agroindustria Mundial (CIESTAAM). Departamento de Zootecnia y Sociología. Carretera México-Texcoco km 38.5, Chapingo, Texcoco, Estado de México. CP. 56230. Tel. 5959521500, ext. 1722. (idominguez@ciestaam.edu.mx; rgranados@ciestaam.edu.mx; sagarnaga.myriam@gmail.com; jmsalasgonzalez@gmail.com; jaguilar@ciestaam.edu.mx).

The tuna, fruit of the nopal, is considered an icon of the Mexican culture, there is evidence of its production and consumption for more than 9 000 years. The objective was to estimate the economic and financial feasibility of tuna cultivation, two representative production units (URP) of different scales (EMNPT04) and (EMNPT25) were constructed in the community of San Felipe Teotitlán, Nopaltepec, Estado de México, in order to generate information to support decision-making. Through the panels technique, technical and economic information was obtained. Based on the methodology developed by the American Association of Agricultural Economists (AAEA), income and costs were estimated to determine economic, financial, and target prices. The estimated production cost is largely covered by the selling price. The net cash flow is positive in both URPs and allows producers to cover family expenses. Both URPs are financially viable. EMNPT04 is not economically feasible. The prices required to cover production costs, including production factors, are 3.92 and 2.37 pesos per kilogram, for EMNPT04 and EMNPT25, respectively. The economic situation of the smaller scale URP is vulnerable, its long term permanence is doubtful. The results are indicative of the URP situation with characteristics similar to those analyzed, in the studied region.

Keywords: Nopalae; Opuntia; production costs; opportunity costs; target prices

La tuna, fruta del nopal, es considerado un ícono de la cultura mexicana, hay evidencia de su producción y consumo desde hace más de 9 000 años. El objetivo fue estimar la viabilidad económica y financiera del cultivo de la tuna, se construyeron dos unidades representativas de producción (URP), de diferentes escalas (EMNPT04) y (EMNPT25), en la comunidad de San Felipe Teotitlán, Nopaltepec, Estado de México, con el fin de generar información de apoyo a la toma de decisiones. A través de la técnica de paneles, se obtuvo información técnica y económica. Con base, en la metodología desarrollada por la Asociación Americana de Economistas Agrícolas (AAEA), se estimaron ingresos y costos para determinar la viabilidad económica, y financiera, y precios objetivo. El costo de producción estimado es cubierto ampliamente por el precio de venta. El flujo neto de efectivo es positivo en ambas URP y permite a los productores cubrir gastos familiares. Ambas URP son viables en términos financieros. EMNPT04 no es viable en términos económicos. Los precios requeridos para cubrir costos de producción, incluyendo factores de producción, son de 3.92 y 2.37 pesos por kilogramo, para EMNPT04 y EMNPT25, respectivamente. La situación económica de la URP de menor escala es vulnerable, su permanencia a largo plazo es dudosa. Los resultados son indicativos de la situación de URP de características similares a las analizadas, en la región en estudio.

Palabras clave: Nopalae; Opuntia; costos de producción; costos de oportunidad; precios objetivo

Introduction

The tuna, fruit of the nopal, is part of the Mexican culture and folklore since the pre-Hispanic time. This fruit is nutritious and healthy, with unique organoleptic characteristics; its cultivation is done using traditional techniques (compatible and respectful with the environment), with low requirement of inputs and investments. Its adaptability allows it to develop in the most hostile environments (Méndez and García, 2006) and (Ramírez et al., 2015), providing a productivity higher than other species, so it is an alternative to poor agricultural land in which would generate food, income and employment for producers with few opportunities (Méndez and García, 2006).

México has a high potential for the development of cactus pear plantations, due to the large agroclimatic plurality under which it is cultivated. In addition, this fruit is gaining importance in the international arena, due to the access to European markets, and producing countries such as Italy, South Africa, Chile and Israel (Ramírez et al., 2015).

According to statistics from SIAP-SAGARPA (2016), national production of tuna has maintained positive growth rates over the last three decades. The production volume increased from 43 000 t in 1980 to 408 000 t in 2015.

About 20 thousand producers participate in its production, in a cultivated area of approximately 65 000 ha. The main tuna producing regions are three; Puebla, Valle de México and the Altiplano Potosino-Zacatecano. The Estado de México contributes 44% of the national production, with ten producing municipalities. The main ones are: San Martín de las Pirámides, Otumba, Axapusco, Nopaltepec and Temascalapa. In 2015, in Nopaltepec, about 2 890 ha were allocated to the tuna production, with average yields of 10.1 t ha-1, which generated an output of 29 198 t. The Distrito Federal and Estado de México are the two main consumption centers of this fruit (Jolalpa et al., 2011), which is an advantage for the production.

The tuna has been the subject of various studies, which analyzed: physicochemical composition (Teran et al., 2015), development (López et al., 2013) irrigation impact on the shelf life composition (Varela et al., 2014) and even its marketing has been studied (Jolalpa et al., 2011) and production costs (Ramírez et al., 2015). The study by Ramírez et al. (2015), analyzes the profitability of tuna produced in the municipality of Nopaltepec, applying the matrix analysis methodology policy (MAP), based on information gathered in 2011. Callejas-Juárez et al. (2006) analyzed the market for nopal and tuna in the Estado de México, which included a profitability section, although this study was carried out several years ago, its results and conclusions are still valid today.

The production cost is the amount of money that must be invested in order to obtain a given product (Parkin and Loría, 2010). Despite the importance of production costs, in the planning and control of the companies, few authors analyze them and most producers do not know them. The most recent studies are focussed on rubber production costs (Vargas et al., 2015), hay (Fernández et al., 2013) and lime (Vera Villagrán et al., 2016), cost of adopting innovations in vegetables (Almaguer et al., 2012) and potatoes marketing costs (Orozco et al., 2013).

The expert panels technique has been successfully used in agriculture, both for sensory evaluations (Gutiérrez and Barrera, 2015), and for other purposes (Lerdon et al., 2008). In the United States, this technique has been widely used by the Research Center of Agricultural Policy, University of Texas A & M (AFPC) (Richardson et al., 2016), in order to carry out prospective analyzes of representative agricultural farms and although this technique has been used in México for the analysis of various Representative Production Units (Sagarnaga et al., 2010; Vargas et al., 2015; Delgadillo-Ruíz et al., 2016), it has not been used to analyze the tuna production.

Therefore, the aim of this research is to determine the economic and financial feasibility of tuna production, for which two representative units of production (URP) of different scale, located in the locality of San Felipe Teotitlán, Nopaltepec, Estado de México. The hypothesis is that they are viable in economic and financial terms and that the production factors invested in this activity are adequately remunerated.

Materials and methods

The producers panels technique was applied (Sagarnaga et al., 2014), in which technical and economic information was gathered as basis for the analysis in this research. As well, two URPs of different scales were analyzed, which were called EMNPT04 and EMNPT25. Which have 4 and 25 production hectares, respectively. The small-scale URP panel (EMNPT04) was conducted in 2016, results were validated on July 7. The largest scale one (EMNPT25) took place on July 7, 2016 and was validated on July 7, 2016. For the construction of the URP, producers were invited whose holdings have similar characteristics, in terms of scale, production system and technological level, among others. The base year for the calculation of revenues and costs was the production cycle of 2015.

In the panels, information was collected on area under cultivation, fertilization, control of weed, pests and diseases, labor use, infrastructure, machinery and equipment required, operating and financial costs, and inputs price. For the revenues estimating, information on prices and yields of the main product, by-products and waste, self-consumption and government support or transfers was collected.

The information gathered was integrated into a database in Microsoft Excel® version 2010. From the technical and economic parameters, fixed and financial costs (CF), variable costs (CV), economic costs (CEc) and financial (CFIN) and net cash flow (FNE) were estimated. Total costs (CT) were estimated by the sum of CF and CV, total income (IT) was obtained from the amount of tuna sold, multiplied by its market price. The net income (IN) was estimated by substracting CT from IT. CFin’s include CF and CV. CEs, in addition to CF and CV, include the opportunity cost of the production factors. The FNE, in addition to CF and CV disbursed, includes the cash required for credits to the principal of long-term credits and withdrawals from the producer. These costs were the basis for calculating target prices, which compared to the selling price (PV) determine the ability of the URP to cover specific production costs.

Costs and revenues were estimated based on the methodology proposed by the labor force for the Estimate of income and product costs, from the American Association of Agricultural Economists (AAEA, 2000). Since revenues are obtained from the sale of the two products with different prices (white and red tuna), a weighted average selling price was estimated. The weighting was done taking as reference the participation of both products in the volume of production obtained. These variables were the basis for estimating cash flow, income and financial (or private) costs, income and economic (or social) costs, and target prices. The latter are those that must be obtained in order to meet certain financial, economic and cash flow obligations.

Once the CEc, CFin and FNE were quantified, the relevant target prices for the URPs were determined. These are the following:

(P1) price required to cover only one unit variable cost disbursed (C1); (P2) price required to cover P1 plus depreciation (C2); (P3) price required to cover P2 plus producer labor and business management (C3); (P4) price required to cover P3 plus capital cost (C4); (P5) price required to cover P4 plus producer withdrawals (C5); (P6) price required to cover P5 plus opportunity cost of production factors (C6); (P7) price required to cover P6 and obtain remuneration for the risk of investing in the activity (C7).

The formula and interpretation is as follows: receiving a price equal to P1 allows the producer to cover only the cost of the variable inputs disbursed, excluding labor (C1). By receiving this price the producer is unable to meet short-term obligations.

Where: C1= variable cost per unit paid, not including labor; CVD1t= total variable costs paid, not including labor; Y= yields obtained under the most likely scenario.

P1 >=< C1 test. If it is greater than, then the company will be able to cover the variable costs disbursed, not including labor; if it is less than, the company will not be able to cover the variable costs disbursed, even without labor. The company faces serious liquidity problems in the short term, which could lead to its closure.

The prices P2 to P6 are calculated in a similar way to P1, adding the corresponding costs and dividing among the yields obtained under the most probable scenario.

Results and discussion

The two types of URP produce under rainfed conditions, on ejido-owned land, with conventional technology, use of hired and producer labor, chemical and organic fertilization. The harvest is done five months a year, June-October. 80% of the production is white tuna and 20% red tuna. For EMPT04, the total yields are 20.4 per hectare; while the EMNPT25, obtained 22.4 tons per hectare. The larger scale URP receives a higher price for the red tuna. Both URP sell to intermediaries, which distribute in local markets (small scale) and other states (larger scale).

Regarding yields Callejas-Juárez et al. (2006), says that these are variables and are related to the low technological level, climatic restrictions, agronomic management and pests and diseases incidence, with regard to seasonality, the same author found that the harvest season from May to October coincides with low market prices (Callejas-Juárez et al., 2006).

Financial analysis

The only income source is the tuna sale, nopal is not harvested, no waste or stubble is sold. It is not representative that the analyzed URPs receive government support.

The larger-scale URP has greater bargaining power, which allows it to receive differentiated prices, and although they also sell to intermediaries, they have as final destination other states in the Republic. The smaller scale URP sells all the production at the same price.

Marketing is a key element in the profitability of tuna production, due to the different problems they face when selling that place them as price takers (Ramírez et al., 2015). Authors like Jolalpa et al. (2011) mention that among the commercialization problems of tuna, there is a strong intermediation in the sale.

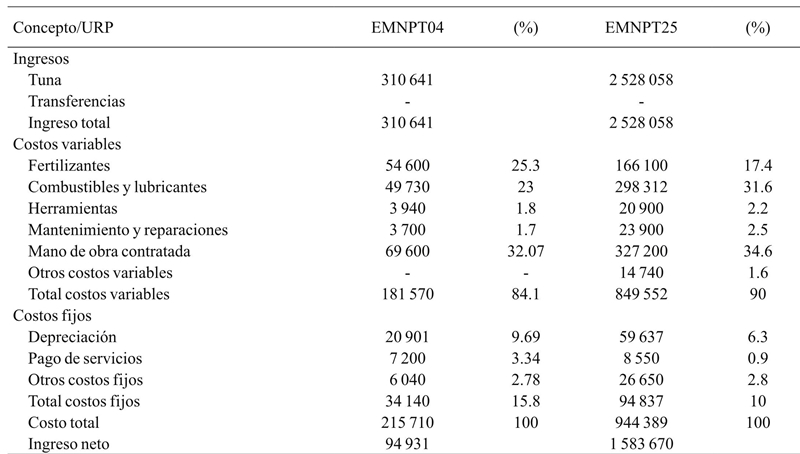

The most important cost concepts are: labor, fertilizers, fuels and lubricants. The contracted labor is the concept of greater weight, because the harvest is done manually and must be done carefully in order to not to damage the plant and fruits and so that the worker is not injured with thorns. Regarding the efficiency in the use of labor, differences are detected, since for the management of 25 hectares ten workers are hired and for four hectares six are hired. The producers could not attribute this difference to a particular activity (Table 1).

Fuente: elaborado a partir de información de campo (2016).

Table 1 Financial budget (total pesos per URP).

The weight of the fertilizers, in the totals, is 25.3 and 31.6%, for EMNPT04 and EMNPT25, respectively. These differences are due to the fact that in the smaller scale URP a greater proportion of organic fertilizer is used, whereas EMNPT25 uses more industrial fertilizers as well as more fumigants.

These results coincide with those found in studies conducted in this same area, where it was found that in the cost structure, labor is the most important concept, weighing 29.5% to 34.5%, followed by fertilizers, with a weight of 19.1 to 22.3%. The concept of fuels and lubricants is not broken down, but could be encompassed in the cost of various materials, having a weight of 28.1 to 32.8 percent (Ramírez et al., 2015).

The URP EMNPT04 has a greater investment in fixed assets. Due to a greater requirement of productive infrastructure, and plastic boxes used in the harvest. This generates higher CF unit costs for depreciation concept. Failures are observed in the efficient use of the productive infrastructure, since the de-thorn used in EMNPT04, has the same characteristics and capacity (550 t) that the EMPT25, and is used to de-thorn only 80 t. This has a negative impact on the unit production cost. These could be reduced by using adequate productive infrastructure to the URP.

The smaller scale URP requires a more efficient use of productive resources, since with the labor it employs and the machinery they have could work with a greater surface area, which would reduce the unit costs.

At the EMNPT04, the production cost of the kilo of tuna is 35% higher than that observed in the EMNPT25, 2.64 and 1.72 pesos, respectively. Although both are significantly lower than the sale prices estimated at 3.8 and 4.36 pesos, respectively.

This confirms the results of Jolalpa et al. (2011), who found that tuna production generates a positive absolute margin for producers. Also it coincides with the results obtained by Callejas-Juárez et al. (2006) who say that for each peso invested in tuna 3.16 pesos are obtained.

In both URP, revenues exceed costs, which makes it possible to capitalize the company and recover the means of production, allowing installations, machinery and equipment to be replaced at the end of their useful life, which guarantees the permanence of the URP in the medium term.

An important factor in the viability of URPs is the difference in yields. The yields obtained by EMNPT25 are higher than those obtained by EMNPT04, for approximately 1.6 t ha-1. The selling price is another determining factor, thus EMNPT25 receives 0.56 pesos more per kilogram than EMNPT04. The difference is explained by the market in which the product is placed, which is reflected in a better price for the producer. Another important difference is that EMNPT04 sells the white and red tuna at the same price, while EMNPT25 receives a differentiated payment for color. These factors are combined so that EMNPT25 receives a higher IT.

Economic analysis

Given that in this URP no transfers are received, and self-consumption is irrelevant, the IT obtained are the same as those obtained in financial terms. In order to estimate the cost of production factors, the information required to estimate the opportunity cost of labor for the producer and capital was collected.

For the opportunity cost of labor, the time that the producer invested in production-related activities was considered and quoted at the rate of a laborer in the area. Management activities were valued considering the time the producer invests in planning, organizing, directing and controlling the URP, which are necessary activities for its development and it was quoted based on the cost of a specialized laborer (tractor driver).

For the cost of fixed capital, the amount of money invested in constructions, facilities, machinery, equipment and planting was considered, and the cost of land was included. For the working capital, all expenses necessary to cover variable costs (inputs, labor, operation, among others) were included. The resulting amount and considering that the URP does not work with short-term loans, was multiplied by an interest rate of 8 percent.

The opportunity cost of the production factors increases costs by approximately 30%. Which coincides with the results of Ramírez et al. (2015) who found that internal factors play a significant role in the cost structure of tuna production.

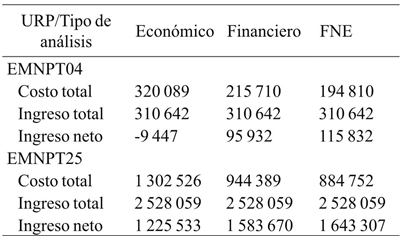

When estimating IN in economic terms, it was found that EMNPT04 shows losses, but not EMNPT25, which is economically viable (Table 2).

Fuente: elaborado con información de campo (2016)

Table 2 Economic, financial and net cash flow production costs (pesos per URP).

The economic cost, which includes the opportunity cost of land, labor and capital, is covered only in the larger scale URP, indicating that the resources employed are invested correctly, and there is no pressure to devote them to alternative activities. This is another factor that guarantees the permanence of this URP in the long term. Not so in the smaller scale URP, where the production factors could have a more efficient use in another more profitable productive activity; which risks its permanence in time. About it Delgadillo-Ruiz et al. (2016) say that the URPs that fail to cover their economic costs tend to disappear if production technologies, evaluated market conditions, or the amount of the transfers they receive are not modified.

Net cash flow (FNE)

In terms of FNE, IT is the same as that obtained in financial terms. The total costs are lower than those obtained in the financial analysis, since in this case the depreciation is not included. Panelists said they did not have long-term credits, so there are no cash needs to cover amortizations. Which is consistent with findings in other studies, in which, among the problems of tuna production, affecting a lower profitability, lack of funding (Ramírez et al., 2015) is mentioned.

The FNE receiving by both URPs is positive. Indicating the existence of liquidity, which allows producers to withdraw money to meet personal and family needs. This makes unnecessary the search for alternative activities to complement the income, allowing the producer to make a better management of the plantation and to carry out managerial activities that favor the development of the URP.

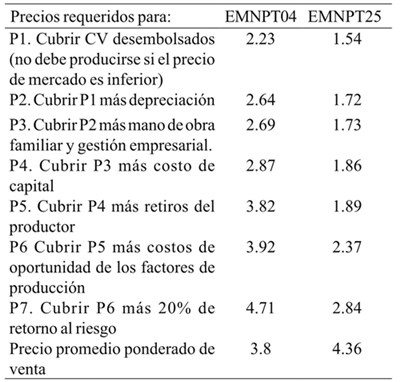

Target prices

The price received by EMNPT04 allows them to cover all the CF, CV, family labor and business management and partially the capital cost. The price that this URP should receive to cover production costs and adequately remunerate the production factors is 3.92 a kilogram. On the contrary, the weighted average selling price that EMNPT25 receives allows it to cover all the production factors and even allows it to obtain a risk remuneration higher than 20% (Table 3).

Fuente: elaboración propia con datos de trabajo de campo (2016).

Table 3 Target prices (pesos per kilogram).

These results show that the larger scale URP is feasible, both in the medium and in the long term; while the smaller scale URP is viable only in the medium term, since the factors of production could have alternative uses in more profitable crops.

Conclusions

Under the economic and technological conditions in which this analysis was developed, the production of tuna is financially viable. This indicates that this activity will remain in the medium term. In economic terms, it is only viable the 25-hectare URP, which obtains higher yields, sells the tuna at differentiated prices by color, receives a better price from regional intermediaries, and makes a more efficient use of productive infrastructure and labor. This also allows a more efficient use of production factors, which under current conditions, have no more profitable alternative uses.

On the contrary, small-scale producers of the URP, by not receiving adequate remuneration for family labor, land and capital invested, nor receiving risk remuneration could change crops when more profitable crops emerge. For this type of URP it is necessary to look for alternative sales that: improve the price they currently receive, increase the yields obtained and reduce production costs.

The analysis shown in this document was based on information provided by the producers, the results were reviewed and validated by them, and are therefore considered indicative of the economic and financial situation of producers of similar characteristics, located in the regions under study. This information can be used in support of decision-making, both by the producer and by the sector policy makers.

Literatura citada

AAEA(Task Force on Commodity Costs and Returns). 2000. Commodity costs and returns estimation handbook. A Report of the AAEA Task. 545 p. [ Links ]

Almaguer, V. G.; Ayala, G. A. V.; Schwentesius, R. R. y Sangerman, J.D. M. 2012. Rentabilidad de hortalizas en el Distrito Federal,México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agric. 3(4):643654. [ Links ]

Callejas-Juárez, N.; Matus-Gardea, J. A.; García-Salazar, J. A.; Martínez Dámian, M. A. y Salas, González, J. M. 2006. Situación actual y perspectivas de mercado para la tuna, el nopalito y derivados en el Estado de México. Agrociencia. 43(1): 73-82. [ Links ]

Delgadillo-Ruiz, O.; Leos-Rodríguez, J. A.; Valdez-Cepeda, R.D.; Ramírez-Moreno, P. P. y Salas-González, J. M. 2016 Análisis de la viabilidad de la producción de frijol (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) En el corto y largo plazo en Zacatecas, México.Agroproductividad. 9(5):16-21. [ Links ]

Fernández, M. A. E.; Stuart, M. R.; Chongo, B. y Martín, M. P. C. 2013.Evaluación del valor nutritivo y los costos de producción del heno en pie y del ensilaje de sorgos nervadura marrón o BMR (Brown Middle Rib). Rev. Cubana Cienc. Agríc.47(2):159-163. [ Links ]

Gutiérrez, G. N. y Barrera, B. O. M. 2015. Selección y entrenamiento de un panel en análisis sensorial de café Coffea arabica L .Rev. Cienc. Agríc. 32(2):77-87. [ Links ]

Jolalpa, B. J. L.; Aguilar, Z. A.; Ortiz, B. O. y García, L. L. 2011.Producción y comercialización de tuna en fresco bajo diferentes modalidades en Hidalgo, México. Rev. Mex. Agron. 28(1):605-614. [ Links ]

Lerdon, J.; Báez, A. y Azócar, G. 2008. Relación entre variables sociales, productivas y económicas en 16 predios campesinos lecheros de la provincia de Valdivia, Chile. Archivos Medicos Veterniarios. 40 (2):179-185. [ Links ]

López, C. C. J.; Malpica, V. A.; Lopez, C. J.; García, P. E. y Sol, S. A.2013. Crecimiento de Opuntia ficus-indica (L.) Mill. en la zona central de Veracruz. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. Pub. Esp.Núm. 5. 1005-1014. [ Links ]

Méndez, G. S. J. y García, H. J. 2006. La tuna: producción y diversidad.Comisión nacional para el conocimiento y uso de la biodiversidad (CONABIO). Biodiversitas. 68 p. [ Links ]

Monke, E. A. and Pearson, S. R. 1989. The policy analysis for agricultural development. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.84-163 pp. [ Links ]

Moreno Alvarez, M. J.; Medina, C.; Antón, L.; García, D. y Belén Camacho, D. R. 2003. Uso de pulpa de tuna (Opuntia boldinghii) en la elaboración de bebidas cítricas pigmentadas. Interciencia. 28(9):539-543. [ Links ]

Parkin, M. y Loría, E. 2010. Microeconomía. Versión para Latinoamérica.9a (Ed.). Pearson. 251-265 pp. [ Links ]

Ramírez, A. O.; Figuero, H. E. y Espinosa, T. L. E. 2015. Análisis de rentabilidad de la tuna en los municipios de Nopaltepec y Axapusco, Edo. de México. Rev. Mex. Agron. 19(36):1199-1210. [ Links ]

Richardson, J. W.; Outlaw, J. L.; Knapek., G. M.; Raultson, J. M., Herbst,B. K.; Anderson, D. P. and Klose, S. L. 2016. Representative farms economic outlook for the January FAPRI/AFPC Baseline. Briefing Paper 16-1. Argicultural and Food Policy Center. Texas A & M University. 18 p. [ Links ]

Sagarnaga, V. L. M.; Salas, G. J. M.; Mendoza, A.; Kú, V.; Delgado, J. L.Díaz, F. R.; Trujillo, J. D.; Díaz, T.; Martínez, R.; Gutiérrez, N.; Lozano, E.; López, J. C.; Robles, L.; González, R. F.; Cigales,M. R.; Barrera, G.; Miranda, M. A.; Magaña, J. E.; González, J.;Montoya, G.; León, N. S.; García, L. R. y Covarrubias, I. 2010.Unidades representativas de producción agrícola. Panorama Económico 2008-2018. (UACH)-SAGARPA. 208 p. [ Links ]

Sagarnaga, V. L. M.; Salas, G. J. M. y Aguilar, Á. J. 2014. Ingresos y costos de producción. 2013. Unidades representativas de producción. Trópico Húmedo y Mesa Central. Paneles de productores. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo (UACH)-CIESTAAM. 334 p. [ Links ]

Orozco, S. C.; Valdivia, A. R.; Portillo, V. M.; Del Valle, S. M.; Gómez,C. M. y Orozco, C. J. 2013. Información de mercados y rentabilidad en papa (Solanum tuberosum L .) en el Valle de Serdán, Puebla, México. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 4(1):103-114. [ Links ]

Teran, Y.; Navas, D.; Petit, D.; Garrido, E. y D´Aubeterre, R. 2015. Análisis de las características fisico-quimicas del fruto de Opuntia ficusindica(L.) Miller, cosecados en Lara, Venezuela. Rev. Iberoam.Tecnol. Postcosecha. 16(1):69-74. [ Links ]

Varela, G. Y.; Caldera, A. A. K.; Zegbe, J. A.; Serna, P. A. y Mena, C.J. 2014. El riego en nopal influye en el almacenamiento y acondicionamiento de la tuna. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 5(8):1377-1390. [ Links ]

Vargas, C. J. M.; Palacios, R. M. I.; Acevedo, P. A. I. y Leos, R. J. A. 2015.Análisis de la rentabilidad en la producción de hule (Hevea brasiliensis Muell. Arg.) en Oaxaca México. Rev. Chapingo Ser. Cienc. Fores. Amb. 22(1):45-58. [ Links ]

Vera-Villagrán, E.; Sagarnaga-Villegas, L. M.; Salas-González, J. M.;Leos-Rodríguez, J. A.; De Miranda, S. H. G. and Adami, A. C. D. O. 2016. Economic impact analysis for combating HLB in key lime citrus groves in Colima, Mexico, assuming the Brazilian approach. Custos e Agronegócio. 12(4):344-363. [ Links ]

Received: May 2017; Accepted: August 2017

texto em

texto em